1,001 Voices on Climate Change

Air Date: Week of June 10, 2022

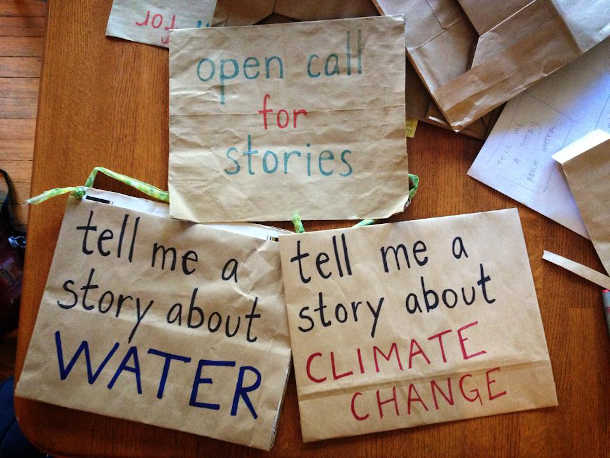

Devi Lockwood’s original “open call for stories” sign, and the two signs she traveled the world with that read “tell me a story about water” and “tell me a story about climate change”. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

Even as the climate emergency grows it can be difficult to comprehend what a degree of temperature change or a foot of sea level rise really means on a personal scale. So journalist Devi Lockwood set out to find the stories of real people coping with climate disruption by traveling in twenty countries and asking people to “tell me a story about climate change.” She joined Host Steve Curwood to share a taste of these “1,001 Voices on Climate Change.”

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

The climate emergency is here and now yet it can be difficult to comprehend what a degree of temperature change or a foot of sea level rise means. But the stories of real people coping with the changing climate can help us better understand and even draw inspiration from this crisis we now all face. Journalist and writer Devi Lockwood set out to tell these stories in her book 1,001 Voices on Climate Change. She spent five years traveling through 20 countries around the world with a sign asking people to tell their stories. During a Living on Earth Book Club live event I invited Devi to share some of those stories and the inspiration for her book. Welcome to Living on Earth!

LOCKWOOD: Thank you so much for having me, complete honor to be here.

CURWOOD: So what got you, you know, getting up and going out to seek 1,001 stories about climate disruption?

LOCKWOOD: Yeah. So in a weird way, some of it started with the Boston Marathon bombing. I was living in the city at the time, as a student, and we were on lockdown for a couple of days. The first thing that I wanted to do when it became possible to go back outside again was to just have conversations, face to face with strangers. And so I had this kind of fit of inspiration. I found a box that had been used to ship broccoli in bulk to the cooperative house where I was living. And I cut that open and covered it with a paper bag and took out a Sharpie, and wrote "open call for stories" on that sign, and then threaded a little polka dot ribbon around the edge of it so that I could hang it around my neck and have this cardboard as a conversation starter with strangers. And I just spent one afternoon wandering around the city for the day, and heard all sorts of stories. And it just felt really incredible, this kind of spontaneous connection with strangers and, and once I started doing that, I didn't really want to stop. And I had planned for myself a bike trip down the Mississippi River that summer, spent a month traveling about 800 miles starting in Memphis, Tennessee and ending in Venice, Louisiana, where the river meets the Gulf of Mexico. And I brought my little cardboard sign. And when I wasn't on the bike, I wore that sign around my neck, and all sorts of people talked to me about all sorts of things. But one common theme that emerged from a lot of those stories was about water and about climate change, in terms of intensifying storms, saltwater encroachment on the land. People, even south of New Orleans, making decisions to leave communities that they had called home for, in some cases, generations in the aftermath of a big storm. And I thought it might be really powerful to put those stories from the Lower Mississippi River delta in dialogue with stories from other parts of the world.

Devi Lockwood’s 2021 book “1,001 Voices on Climate Change: Everyday Stories of Flood, Fire, Drought, and Displacement from Around the World”. (Photo: Courtesy of Tiller Press and Simon & Schuster)

CURWOOD: And when you asked people to speak to you, you actually had two signs: you had "tell me a story about climate" and also "tell me a story about water." Why those two?

LOCKWOOD: Yeah. So when I was on that bike trip down the Mississippi River, it became apparent to me that we don't always have the words to talk about these impacts, but that by using stories, it can be a way in. But also, you know, I think the language we use to talk about climate change a lot of times is really abstract and sometimes inaccessible. It can be hard to feel what a degree of temperature change is, or a foot of sea level change. And so my hope was that putting stories to that would just make it easier to understand. And water -- water is even easier to talk about, right? Everyone has a water story. Water is threaded throughout our lives. And many, not all, but many of the impacts of climate change are things that people experience through water, whether that's an overabundance of it in a flood, an acute lack of it in a drought, sea level rise. And so I wanted to give an inroad to being able to discuss these two issues in tandem.

CURWOOD: Gotta ask you about that title. Of course, I guess this is an allusion to Scheherazade, and most people probably know that story, but just remind us a little bit about it.

LOCKWOOD: Yeah, sure. So this is a story that is very old. [LAUGHS] And that was originally told orally, got written down, passed down over time, and there's been kind of small tweaks. But the version that I know, goes a little something like this. So there was a King named Sharyar, and his wife cheated on him. And he, in a fit of rage, chopped off her head and decided that that wasn't enough, that he would have a vendetta against all women in the kingdom. So he would wed and bed them one by one, and then chop off their head in the morning. And so it finally became Shahrazad's turn to have to go through this. And she is a trickster, so she decides that she is going to tell the king a story. And that story ends with a cliffhanger at dawn. And so he gets to dawn and he really doesn't want to kill her because he wants to know how the story ends. And then she does this night after night after night after night, for 1,001 Nights, at which point it's been three years, they have maybe a kid or two and he decides that he's not going to kill all the women anymore. And what I found particularly moving about that series of interlocking tales, is that Shahrazad tells these stories not only to save her own life, but to change the culture in her kingdom. And I thought it might be fun -- you know, it started out as a joke, I told my friend, I was like, what if I did 1,001 of these interviews? There were kind of more twists and turns to the journey than I could have imagined.

Devi wearing her sign in Bluff, New Zealand. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: Yeah, for example? -- well, well take me on a tour of where you went and some of those twists and turns.

LOCKWOOD: Well, I started out in the South Pacific. Part of the inspiration to go there was from an article I had read about the idea of climate refugees going from Tuvalu to other countries, primarily Fiji and New Zealand. And when I spoke with Tuvaluans, they don't like to be called climate refugees, like climate migration is a better kind of term for the people as they'd like to define themselves. But Tuvalu is this low-lying coral atoll nation, about 585 miles south of the equator. And the kind of low-lying nature of this island nation makes it extremely vulnerable to sea level rise, and changes in rainfall patterns and other impacts of climate change. And these are most intimately experienced through both food and water insecurity. So there used to be a freshwater lens under the island. And in the early 2000s, that became salty from changes in the level of the tides. And the seas have been rising at about four millimeters per year since they started monitoring it a couple of decades ago. And that doesn't sound like a lot, but again, really dramatic impacts. When I was there, I asked one of the girls in the host family that I was staying with if she could take me out to see the wells that they used to have to drink water. And she's like, why would you want to see that? It's, there's nothing there. But we went and it's kind of been repurposed as a trash heap. And each family has a big rainwater tank that's attached to the roof. And when it rains, every drop is precious, right? So people are really good at conserving water and making do what they have. But then in times of drought, that scarcity means that they have to make really difficult decisions about, about allocating it.

Devi wearing her sign on the Great Wall of China. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: As you look back, Devi, at your travels, what are the threads that you pull from these stories to make the fabric of how you would distill this experience? What's common? What's common, and then kind of what starts to differentiate people dealing with this story of climate -- climate change, you say climate disruption, is really what we have, I think.

LOCKWOOD: Yeah, I mean, the thing about climate change is it's a global problem with very hyper local impacts, right? And so I met people who were mourning the loss of five of their best friends from a wildfire in Australia, right, or a man in Thailand who made the choice to move from the rural North to Bangkok, because changes in rainfall patterns had made the rice farming practice of his ancestors just not possible to rely on anymore for a livelihood. And the way that I have come to think about these themes over time. I mean, there's, there's a couple of threads, right? One of them is that climate change drives food and water insecurity. And that that forces people into really difficult scenarios. Another one is that climate change is an environmental justice issue. So the people who are first and worst impacted by these changes are more often than not already experiencing different forms of systemic and structural oppression that make it even more difficult for them to respond to those problems. And also, they're not the ones who have emitted the most greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to begin with, right, so they're the least responsible for it. And another thread -- this is maybe a bit kind of the thread above the threads. But what I was trying to do in this book was to diversify the idea of expertise. Because it's really important to me that we acknowledge at this point, that people are experts in their own lived experience. And that that form of expertise is as valid as what we might conventionally think about as a climate science expert, who's you know, either has a PhD in atmospheric sciences, or has spent time studying ice cores in Antarctica, right, or, or monitoring permafrost melting in Sweden. All of these things are massively important. And there are some of those interviews in the book. But when we consider that science and that form of expertise side by side with the voices of people who are living with the impacts of climate change right now, I think it just becomes harder to ignore the problem, right? Humans are storytelling creatures. And storytelling is it's one of the most ancient technologies that we have. And I have to believe that we can leverage that as a climate solution as well.

Devi conducts an interview wearing her sign in Chengdu, China. (Photo: Va Sha, Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: One of your stories, you go right into the heart of the climate bureaucracy debate, the talks there in Marrakech in 2016. Tell me about that. Tell me about who you met.

LOCKWOOD: One of the really incredible people who I met while I was there is Gertrude Kenyangi, and she is a Ugandan forestry activist. And she comes from a community in southwestern Uganda where small scale agriculture is the kind of main economic activity. But she was at the Conference of the Parties to advocate for gender equality in climate policies, and solutions, because she told me that the people who are the most impacted by climate change are those who are not able to adapt, and they can't absorb the shock. And so it's just almost impossible for people to bounce back from any climate disaster. And she added that women in particular are very vulnerable. And so in Uganda, climate change is impacting agriculture. And she's seeing this, whether it's prolonged droughts, or violent rains, or landslides, even, that can be deadly. And yeah, she's continued when possible to travel to COP to just advocate for how important considering women and considering women in agriculture in Uganda is in these types of negotiations.

To avoid carbon-intensive air travel as much as possible while traveling the world, Devi rode many miles on her bike and even hitched rides on cargo ships and sailboats. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: Well, this part of your set of stories has a wonderful set of lines. I, I wonder if you wouldn't mind turning to page 207, I think it is.

LOCKWOOD: Okay. Sure.

CURWOOD: And read the last two paragraphs of Gertrude's story.

LOCKWOOD: Yeah, sure. "When you think about Uganda, specifically, what does climate change there smell like or sound like or taste like?" I asked. "It tastes like a shortage of food. It tastes like shortage of water, because our agriculture is rain fed. And we are dependent on natural sources of water," she told me. "So when the aquifers dry up and our crops fail, it smells like disaster. It's so evident that climate change is taking place. The seasons have shifted. When we expect rain, it doesn't come. And when it comes, it's too short a duration. You cannot plant anything. So we don't have any fallback position. We don't have reserves of food. We don't have money stashed in the bank. We live day by day."

Devi with two local women and her sign in Fiji, which is facing the threat of sea level rise due to climate change. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: So what prompted you to start asking this question of what does climate change smell and taste like to people? When did that emerge in the process, that you would get some pretty powerful answers if you asked people that way?

LOCKWOOD: Yeah, you know, I think I was just trying to get sensory. I was thinking about what makes a good story and the elements of good storytelling. And sometimes, especially in these like UN negotiating spaces, we can speak at a really high level about, you know, overly intellectualizing it just because that's the ocean, the water that we're swimming in, the language that we're surrounded by, right? But in fact, breaking it down to, to senses, and to things that we can taste and smell, and, and feel, makes it feel all the more immediate. And yeah, it felt like an important question to ask in that moment. And in a couple of other moments as well.

Devi wearing her sign in Fiji. (Photo: Courtesy of Devi Lockwood)

CURWOOD: In many cases, this must have been cathartic for people, right, to actually tell you something, maybe even come to realizations themselves as to how the climate emergency was proceeding in their lives. We have a few more moments can you, can maybe this -- what comes to mind to me among your, your narratives is a woman who was brought up in Florida who talked to you.

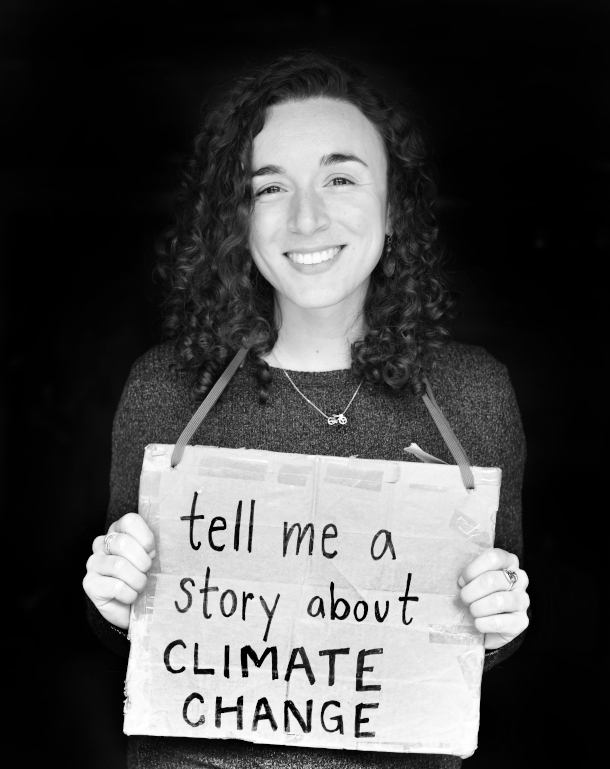

Devi Lockwood with her cardboard sign that reads “tell me a story about climate change”. (Photo: Courtesy of Tiller Press and Simon & Schuster)

LOCKWOOD: Yeah, yeah, we, we met at a climate march in DC. And she told me about diving in the coral reefs in the, in the Florida Keys when she was a kid and just being wowed by the colors and the vibrancy of life there. And she hadn't been there for a couple decades and then returned as an adult. And the majority of that coral was bleached and dead. And she just started sobbing, right? It was so clear how much of a sense of loss she felt. But there's a word for that kind of, experiencing that deep kind of loss and it's solastalgia, right. And so I think that there's ways that we have to cope with, just like you mentioned, the emotional aspect of these changes, right? It's, they're easy to ignore, but I think it's, like many things, just so much better when we talk about it.

CURWOOD: Devi Lockwood is author of the book "1,001 Voices on Climate Change." Devi, again, thank you so much.

LOCKWOOD: Thank you, it's really a joy to be in conversation with you all tonight, thank you so much.

Links

Watch the full Living on Earth Book Club interview with Devi

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth