Ozone-Killing Chemicals Declining

Air Date: Week of November 11, 2022

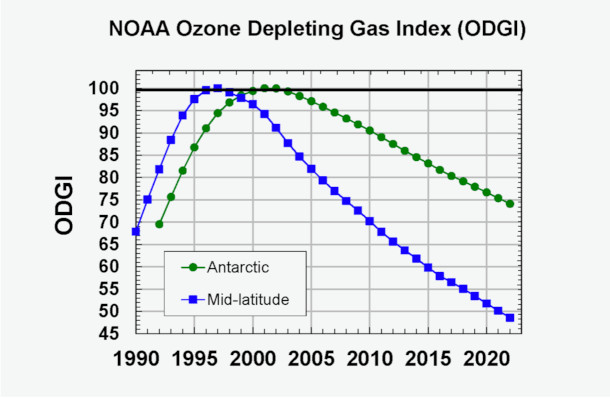

The NOAA Ozone Depleting Gas Index (ODGI) tracks the overall stratospheric concentration of ozone-depleting chlorine and bromine from long-lived ODSs relative to its peak concentration in the early 1990s. Relative to that peak, ODS concentrations have decreased by 25%in the Antarctic, and by 50% over midlatitudes. (Photo: Courtesy of NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory)

Emissions of chemicals that tear holes in the protective atmospheric ozone layer have been drastically reduced, thanks to the Vienna Convention launched in 1985 and its related Montreal and Kigali protocols. NOAA recently reported that midlatitude atmospheric concentrations of ozone depleting chemicals have declined about 50% compared to peak historic levels. Steve Montzka, senior scientist at the NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory, joins Host Steve Curwood to explain how the global community reached this milestone.

Transcript

CURWOOD: As the world gathers in Egypt at the COP27 climate summit, another international treaty cast from the same mold is yielding positive results. Emissions of chemicals that tear holes the upper-level atmospheric ozone layer have been drastically reduced, thanks to the Vienna Convention launched in 1985 and its related Montreal and Kigali protocols. The treaty phases out synthetic chemicals including refrigerants that deplete ozone, a form of oxygen that protects life on earth by filtering harmful ultraviolet rays. It takes time to change the chemistry of our entire atmosphere, but now nearly 40 years after the world started tackling the problem there is resounding success. NOAA recently reported that the midlatitude concentrations of ozone depleting chemicals have declined by 50% compared to peak historic levels. And near the South Pole, they’re down by 25 percent. For more I’m joined now by Steve Montzka, he’s a senior scientist for NOAA’s Global Monitoring Lab. Steve, welcome to Living on Earth!

MONTZKA: It's nice to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So at this present rate of getting back to the pre-ozone depletion levels, how long do you think it will take us to get there?

MONTZKA: Every four years, the science community comes together to inform the Parties to the Montreal Protocol about the state of the science. And the latest report is just about to come out. And it still looks like that ozone layer will return to pre-ozone hole conditions sometime in the middle of the 21st century, 2050, 2060. Around that era.

Chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, were widely used as refrigerants until the 1980s. CFCs are considered an ozone-depleting substance and a greenhouse gas. (Photo: switthoft, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, there was a process that the world went through to deal with ozone depleting chemicals. First Vienna, and then the Montreal Protocol. And countries agreed, of course, to reduce the use of these chemicals. So what do you think was key though, for compliance? What is it that encouraged nations and companies to comply with the Montreal Protocol? There's not exactly an ozone cop out there.

MONTZKA: No, that's true. I think of a few things that caused folks to really pay attention to this issue. I think we have to remember that the ozone layer itself is critical for life on Earth to exist as we know it today. And so, in 1985, when Joe Farman and his colleagues indicated that, “Oh, my goodness, ozone in the stratosphere, over Antarctica was dropping like a rock,” people stood up and noticed, and began to really wonder about what they could do. I think when I listened to recordings of scientists and policymakers from the 1980s, after that announcement was made, I hear the fear in their voice. You know, the concern was that we were looking at the proverbial dead canary in the atmosphere, that ozone was dropping precipitously. And it was because of actions and emissions that humans had produced. It was because of things that we were doing. And so they stood up, took notice and took action. I think the other thing that made a difference was that the actions that were taken initially were only small steps. Policymakers acted rapidly, but only incrementally. You know, the 1987 Montreal Protocol by itself wouldn't have resulted in the eventual healing of the ozone layer. But through this iterative process, where the policymakers get together, decide what they can agree on, and then going to the scientists for input and updates and further understanding improvements in our understanding of the issue itself, and then coming back together as policymakers to decide whether or not they needed to strengthen the Protocol, or possibly weaken it, as a result of the new information. We've had amendments to the protocol over time that eventually resulted in CFCs and other ozone depleting gases being banned. And countries abiding by those bands for the most part.

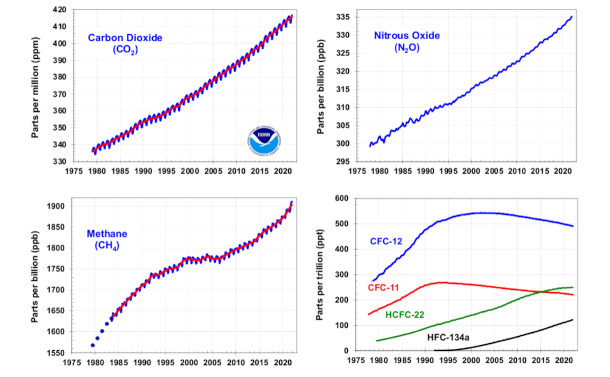

The concentrations of ozone-depleting substances have decreased over time since the 1990s. However, NOAA’s research shows that global concentrations of other greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane, continue to increase. (Photo: Courtesy of NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory)

CURWOOD: So the trend is going in the right direction. What do you think needs to be done on a broader scale to maintain this downward trend? What does the global community need to do to keep countries and companies, dare we say, in line when it comes to regulating ozone depleting substances?

MONTZKA: Well, Steve, I think we need to look at the recent past to understand what's worked. I think it's been a process of the Parties to the Protocol meeting regularly to assess the science and the new information that's being provided to understand whether or not changes in the ozone layer are happening as expected. Those parties still meet two times per year to assess these considerations. You know, it was only a few years ago, when we noted that CFC11, a few years after global production was supposedly banned, we saw CFC11, its concentration, decline more slowly over time. In fact, we could infer that emissions of CFC11 were increasing, started increasing a few years after the production was banned globally, which was quite a surprise. But it turned out it really seemed like somebody was violating the Protocol.

CURWOOD: Uh oh.

MONTZKA: And the year after we raised the flag to suggest that, “Goodness, things aren't changing, as expected, and it really looks like somebody may be producing and using this chemical again,” some measurements made downwind of that region really pinpointed the location. And you know what, Steve, since that time—that was mid 2018—the concentration decline of CFC11's been rapidly accelerating, which is great to see.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol of the Vienna Convention successfully phased out global production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances. Parties to the Protocol still meet twice a year to assess the science and propose amendments. Shown here is Vidar Helgesen, Norway's Minister of Climate and the Environment in 2017. (Photo: Rwanda's Ministry of Environment, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What was the region that seemed to be the source?

MONTZKA: My initial study suggested that it was emissions from Eastern Asia, and then the subsequent study was able to determine that it appeared to be that emissions were increasing in an unexpected way from Eastern China.

CURWOOD: So the success of what you say is an iterative process, how might that be applied to climate disruption? Because like discovery of the ozone hole, science has been sounding the alarm about the release of climate-changing gases and the road that we're on right now if we don't effectively address it. And so far, we're not there in terms of reining in climate disruption.

MONTZKA: Yeah, it's clear that the trajectories of greenhouse gases haven't turned over like they have for ozone depleting substances. Greenhouse gas concentrations are still increasing rapidly in the atmosphere, and at this point more rapidly than they have, you know, over the past 100 years or more. So what will it take? I'm not sure, there is a process in place that provides feedback. And so the state of the science is there for folks to see. But the issue is perhaps much more complicated, and has many more players involved, then the issue of ozone depletion.

CURWOOD: For example?

MONTZKA: Well, when we're talking about ozone depleting substances, there were a limited number of companies around the world that produced these chemicals. And I think, when the issue of ozone depletion arose, they ultimately decided that they were able to make some substitutes that were less threatening to the ozone layer. So maybe you had an industry down the street or in a in a town that initially created CFCs. But they could retool to make the substitutes. And so it was, perhaps I won't say an easy transition for them, but one that didn't cause huge disruptions in the locations of industries and the employment of local communities and things like that. Whereas when we're talking about climate change, and all the different industries involved in supplying energy, the problem seems much more complex.

CURWOOD: Steve Montzka is a senior scientist for NOAA'S Global Monitoring Lab. Thanks for talking with us.

MONTZKA: Steve, it was very nice talking with you.

Links

NOAA | “Path to recovery of ozone layer passes a significant milestone”

NOAA | “Antarctic ozone slightly smaller in 2022”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth