Extreme Weather and the Jet Stream

Air Date: Week of January 13, 2023

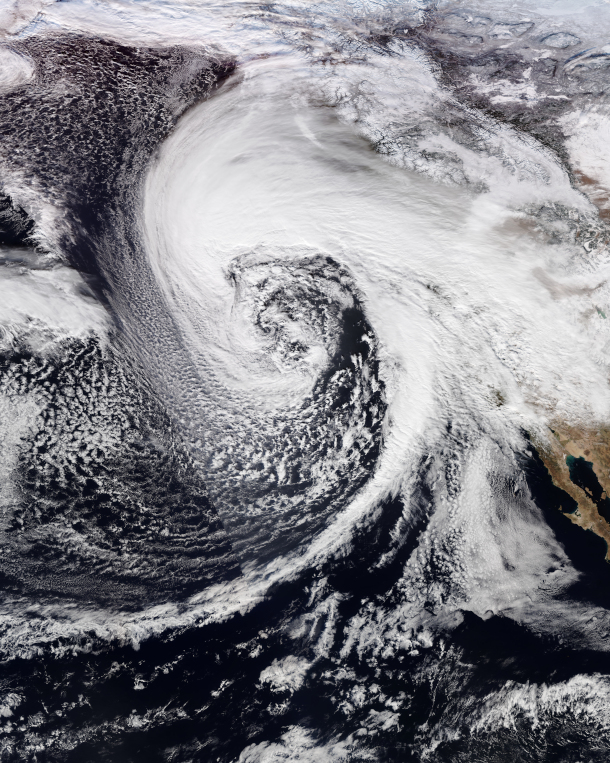

The northwestern United States bomb cyclone in January 2023. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Weather records are now routinely getting shattered across the United States, with recent severe rainstorms in California, freezing temperatures in Texas, and a warm January thaw for the northeast. Jennifer Francis, Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why a climate disrupted jet stream is behind much of this extreme weather.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

2023 has barely begun and already weather records are being shattered around the world, including the severe rainstorms in California.

ANNOUNCER: The city of Santa Barbara is seeing about 6 inches of rain yesterday alone. Flooding homes and major highways with more rain on the way.

ANNOUNCER 2: North bound of the 101 shutdown because of this. What is typically a babbling creek is now a raging class 5 river. This is what 6 inches of rain on top of saturated ground looks like.

ANNOUNCER 1: A new round severe weather is now triggering flood waters in areas at risk of mudslides because previous wildfires that have made vegetation less stable.

BASCOMB: At the same time parts of Europe experienced a heat wave that had many ringing in the New Year in t-shirts. Meanwhile on the south coast of the US, Florida broke heat records and much of Texas plunged to below freezing.

CURWOOD: It seems the pace of human-induced climate disruption is gaining steam, so we called up Jennifer Francis, Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. She studies how the rapidly warming Arctic affects our weather. Jennifer, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FRANCIS: Thank you so much. It's great to be back.

CURWOOD: So it seems like month after month, year after year, there are more extreme weather events happening. How true is that perception?

FRANCIS: It's absolutely true. It's measured not only by scientists like me who study the climate system, but also by companies like insurance companies that really care about these extreme events, because of course, they cost a lot of money. And they end up shelling out a lot of compensation for damages. And so there's absolutely no doubt that we're seeing an increase in the frequency of extreme events of many kinds. Not all kinds, but most of them, I would say.

CURWOOD: So in the Northeast United States, where we're based, we went from below zero temperatures, it seemed like, towards the end of 2022 to shirtsleeve weather. We saw the city of Buffalo get buried under, I don't know if there are measuring sticks for the amount of snow that they got. What's the reason behind such sudden changes and events like that? Suddenly, a bunch of snow being dumped, suddenly the temperature changing?

FRANCIS: Well, you know, pretty much all the weather that we experience around the northern hemisphere in the wintertime is caused by fluctuations in the path of the jet stream. And the jet stream is this river of wind that blows from West to East, high up in the atmosphere where jets fly. And the jet stream really does create all of our weather and steers storms, it steers high pressure areas and low pressure areas. So, whatever is going on with the jet stream is felt by us down on the surface as changing weather. So what happened over the last several weeks, where it caused those big flips and extremes, as you said, first, it was extremely cold. When we experience extreme cold like that, it means that the jet stream has dipped south of us. And when it does that, it's basically the boundary between the cold air to the north, and the warm air to the south. And so when it is south of your location, that cold air from the north can plunge way far south. And in this particular case, it was a very cold airmass that came down from far northern Canada, came down over the whole middle of the country, and caused a lot of problems for places that really aren't used to dealing with the cold. And, you know, it's sort of a flashback to what happened back in February 2021, when Texas and Oklahoma and some of those southern central states got whacked by that very severe cold spell. It was the same kind of thing, it was a big southward dip in the jet stream. So conversely, when that dip goes by your area, you can be in a place where the jet stream swings way north of you. And then that allows the warm air from the South to penetrate maybe much farther north than usual. And in this case, again, it was a very extreme case of the jet stream bringing all this warm air from the south and bathing the Eastern two thirds of the continent in very warm air. So it really just depends on where you are relative to these northward and southward dips in the jet stream. That is what our weather is created by.

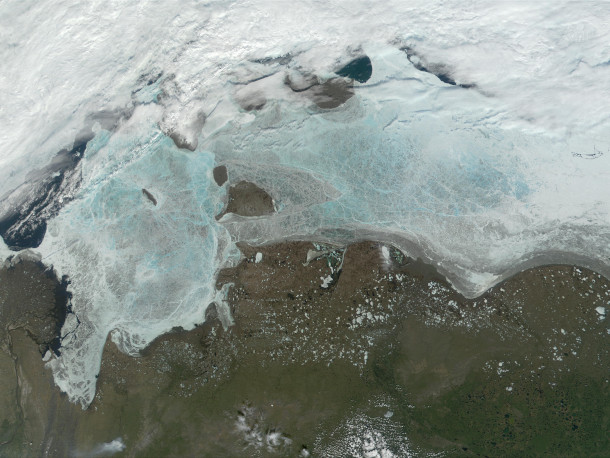

Over the last 40 years, Arctic Ocean surface sea ice has reduced by half. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Now, you've done a fair amount of research on why the jet stream is behaving in such extreme ways, going so much further south than it might have in periods past. And I believe that research is related that to the warming and the formation of Arctic ice. Can you explain what your research tells us?

FRANCIS: Sure. So I should start though, by saying that, you know, the jet stream is a very complicated feature in our atmosphere, our atmosphere is a very chaotic beast, if you will. And there are many factors that can affect the jet stream. So you might know and your listeners might know that right now we are in what we call La Niña conditions. And it's when there's a big pool of colder than normal water extending from, say, the coast of Peru all the way across the Pacific along the equator. The opposite of that is El Niño. And we know that's basically when there's warm water instead of cold water there. And that has a lot of weather implications and it can affect the jet stream. But it's true that my research that I've been doing over the last decade or so, along with a lot of colleagues around the world now, all looking into the various ways that climate change is influencing the path of the jet stream, the strength of the jet stream and therefore weather patterns as well and extreme weather. And one of the factors that we think is a very important one is the fact that the Arctic is now warming about four times faster than the globe as a whole. This has resulted in about half of the sea ice, which is the ice that's floating on the Arctic Ocean, disappearing in the summer, over the last 40 years. So we've literally lost half of the sea ice cover in 40 years. And if you take into account how that ice has thinned, you can multiply the thickness of the ice times this coverage and you get the volume, the volume of the ice has decreased by almost three quarters in that same time period. It's just a huge change to a very important component of the climate system. It's happened over a very rapid period. And there's absolutely no way that a change of that magnitude is not having an impact on the atmosphere and the jet stream. And so the real difficulty in the research now is to figure out exactly how, and it won't be the same in every case, because as I said, there are many factors that affect the jet stream, this being just one. But in a nutshell, what we think is happening because the Arctic is warming so much faster than the rest of the globe, and particularly areas to the south of the Arctic, it's really that north-south temperature difference. So it being warm over the United States, say and much colder in the Arctic, when that temperature difference is large, the winds of the jet stream are strong. And when the winds of the jet stream are strong, it tends to blow relatively, in a straight path from west to east and it circles the whole northern hemisphere. But as we warm the Arctic much, much faster, it means that north-south temperature difference is getting smaller. And when it's small, the winds of the jet stream weaken. And a weaker jet stream is more easily deflected from its west to east path by things like mountain ranges. And even ocean heat waves, is a term that some of your listeners might have heard before, it's basically a blob of very warm water in the ocean. And that can also influence the path of the jet stream. So what we're seeing though, is that the Arctic is warming so fast, we are able to measure weakening of the winds of the jet stream. And we have also been able to measure that the jet stream is now wavier than it used to be, it is taking on these big north-south swings more often than it used to.

CURWOOD: And I think last summer, when people were talking about the huge heat waves that they were talking about double jet streams. Did I hear that, or are my ears not working?

FRANCIS: Well, it's, it's not so much a double jet stream as the jet stream splits into two branches. So I mean, it's the same thing, I guess. But what we see is that oftentimes in the summer, especially now it's happening more often, we're seeing the jet stream split into two branches. So one branch would, say, blow along the Arctic coast, say along the north coast of Europe, for example. And then the other branch would go through the middle of Europe. And this is a summertime phenomenon that we're talking about right now. And when we see this happen in the summer, what happens is the space in between there, those atmospheric features, so high pressure, low pressure, whatever, they don't have any winds to blow them along. So they tend to get very stagnant in one place. And if you happen to be stagnant in a place where there's no rain, the sun's beating down, no clouds, so a high pressure area, then that tends to build up the heat, it dries out the soils, and it leads to these very intense and persistent heat waves. But it can also affect places where it's in the rainy part. So a low pressure area in the same region that's that's basically stuck in place. And that has contributed to some massive flooding in places like Pakistan and other places over the years. So those have been connected to this tendency for the jet stream to split more often during the summertime.

CURWOOD: So the intense weather we're seeing in the wintertime, the intense weather of the summertime, all related to how the jet stream is doing. How much of this sort of change in behavior of the jet stream over this period of time is related to overall warming of the planet?

FRANCIS: Well, I think we should probably back up just a little bit, not every impact of climate change is related to the jet stream itself. There are some very direct connections between the warming globe that we're causing by building up greenhouse gases in the atmosphere through our carbon emissions, and some extreme weather events. So we are clearly warming the globe. And this is directly related to more intense, more long-lived, more frequent heat waves that we've been seeing. So you know, that is a pretty intuitive connection there. That warmer air is also sucking more moisture out of the soil. And so evaporation is increasing everywhere over the oceans and over land and where that evaporation is taking the moisture out of the soil. We're seeing, of course, worse droughts and that has a direct effect on agriculture. So those are two very directly linked weather extremes to climate change. And another aspect of that increased evaporation is that there's now more moisture in the atmosphere, that moisture is absolutely critical, it has a lot to do with how intense a storm gets, how much rain it drops. And that extra water vapor is also a greenhouse gas. So it's exacerbating the heat trapping of the atmosphere. So those are very direct connections between climate change and the kinds of extreme weather events we've been seeing happening much more often. The connections to the jet stream are, I would say, still a very active area of research. And as I said in the beginning, it really depends on what other factors are in play at the same time as, say, the Arctic is warming, or we've got an ocean heat wave, or we have a La Niña. You know, all of these factors play into it. And it's really tough to, you know, disentangle one factor from all the others and say, you know, this particular extreme event was because of that factor, or how much by that factor.

CURWOOD: Welcome to a warming planet. Is that the right title of what's going on?

FRANCIS: Yeah, or another possible title would be the climate crisis is here. You know, it's not for our grandchildren, it is already here. We are already feeling the effects of the warming that's already happened in the climate system, because of our emissions of greenhouse gases and the thickening of this blanket that we're putting around the Earth. So these more intense downpours of rain, more intense, tropical storms, more rapidly intensifying storms, more intense droughts, and long lived droughts, wildfires, these atmospheric rivers that are affecting California this week, all of these things are absolutely symptoms of the changing climate that we've been expecting to see. And here they are, right now, they're happening to us today. They're causing a lot of damage, both in terms of infrastructure, and costs, and lives. And this is the climate crisis. It's already here.

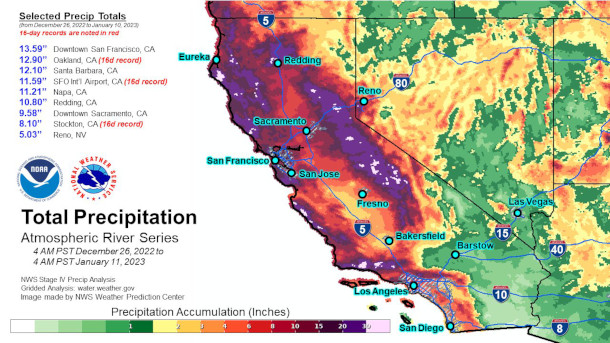

Total precipitation for California from December 26, 2022 to January 11, 2023. (Photo: Weather Prediction Center, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: But wait, the folks in Paris, in 2015 said that we needed to keep it below one and a half degrees centigrade rise in global average temperature, but I think we're only up, what, 1.2 degrees average global temperature?

FRANCIS: That's true. Well, every 100th of a degree that we increase the global temperature, we're going to see that many more extreme events happening. And it's not a hard threshold. It's not that you know, if we can keep it below 1.5, that we're out of the woods, because we're already in the woods, we'll just be deeper into the woods. The warmer it gets, the worse it's going to get. And, you know, 1.5 is a target. It's something that we can aspire to. And I think you know, it's going to be a tough one to, to meet, but it's still possible barely. But as I said, you know, every bit of warming that we can prevent is going to make these extreme events a little less likely.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, I have to mention that some folks would say, there have always been warmer than average winters and colder than average winters and hotter summers and colder summers. And they'll say, well, how much of this is due to natural variability and weather as opposed to disrupting the climate? How would you respond to such questions?

FRANCIS: Well, I would agree that they've always been colder than normal winters colder than normal, summers, wetter, drier, all of those things. But what we see now are trends that are way beyond what is considered natural variability. You know, we've heard the word unprecedented used in extreme events so often in the last couple of years. That means that it's never happened before. And we've seen these unprecedented events unfolding, and clear trends in many kinds of these extreme events. So there's only one kind that is maybe some good news. And that is that we're not breaking cold records as often as we used to. And we're breaking many more high temperature records than we used to. So that kind of goes along with the general warming. But that doesn't mean we still can't get these very extreme cold spells like we've had this winter and also back in 2021, those can still happen. And that's where this very complicated topic of how the jet stream is behaving comes into play, because it isn't just average warming, or average cooling. It's these pulses of cold air that can come down when the jet stream gets into one of these very wavy patterns. So you know, that's another kind of variability, but we're also seeing what looks like the jet stream taking more extreme paths. And this is something that we also expect.

The Arctic is warming three to four times as fast as other parts of the globe. Warmer temperatures will make storms like Merbok much more likely in the future and further exacerbate other ongoing climate hazards such as permafrost thaw, flooding, and erosion.

— Woodwell Arctic (@woodwellarctic) December 6, 2022

(????️: @g_fiske) pic.twitter.com/dadfrkdYxg

CURWOOD: Now we started to see the term weather whiplash, used to describe situations like what we've seen in California or in the Northeast. How is that term defined, if it has, indeed any kind of scientific basis? In fact, what does climate science say about so-called weather whiplash?

FRANCIS: That's a great question because we just published a paper on weather whiplash a few months ago. And there is no, I would say, agreed upon definition of what it really means. But sort of conceptually, it's when you've been in one kind of a weather regime for a while, you get used to, say, above normal temperatures during the winter along the east coast, and all of a sudden, this new airmass moves in, because that wave in the jet stream has passed you by. And all of a sudden, now you're thrown into cold or snowy or very different conditions from what you have been having for the last week or so. And this paper that we've just published, actually takes a look at weather whiplash from a different angle. And that is to look at these continental scale patterns in the jet stream. And measure when they get kind of stuck in one place in one pattern, and then look at when it shifts to a very different pattern. And thinking about that as a weather whiplash, because usually, it's not just one location that experiences it, it's a big shift in the whole atmospheric regime, or the whole pattern across the continent. And so we wanted to characterize it in terms of these, you know, really continental scale shifts, rather than just a sort of ordinary cold front passing through Dallas, Texas, or something like that.

CURWOOD: So in the western US, they've been facing extreme storms and flooding after years of drought, right and wildfire. What's going on there?

FRANCIS: Getting back to this connection to the jet stream, I hope everybody takes away from this discussion that they need to understand that the jet stream is really controlling all the weather that we experience in the wintertime. So what had been happening in the West for a very long time is a tendency for one of these big northward swings in the jet stream to be parked over the West Coast. And that steered most of the storms up into British Columbia and up into Alaska, and away from California and the southwestern states. So they were left high and dry. But now what we're seeing is a very different pattern in the jet stream. We're seeing one of the southward dips just off the west coast. And when we see that happen, just downstream from that big dip in the jet stream is where you get storm development. And so it's been sitting there for days now and developing these very strong storms coming in to the West Coast, there's a lot of cold air coming down from the Arctic, fueling these storms, and a lot of moisture over the very warm tropical oceans that's being sucked into the storms as well. So, you know, any storm that forms today is forming in a different atmosphere from what it was a few decades ago. And so it has more moisture to work with, which means it's going to dump more precipitation, that moisture is also a source of energy for the storm to feed on and become more intense. And so as I said, you know, yes, storms have always hit California. We've always had these kinds of patterns. But we're seeing them on steroids now. We're seeing them fueled by more moisture, by more heat in the oceans. And so it's not just your run of the mill storm anymore. It's this extreme flooding event that California is still dealing with.

Jennifer Francis is a Senior Scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Woodwell Climate Research Center)

CURWOOD: There was a paper published in Nature Climate Change earlier this year that said it's been 1200 years since the American West has had such a prolonged, profound drought. And the decades-long drought that has gripped the West since the year 2000 is the driest 22 year period since at least AD 800. What's going on there?

FRANCIS: Yeah, it goes back to what I was saying that you know, the air is warmer now. And it is more able to suck that moisture out of the soil. Once the soil dries out, that is a big deal, because when soil has moisture in it, that heat that it absorbs from the sun goes into evaporating that moisture so the soil doesn't warm up very much. But once it's dry, all of that energy from the sun goes into heat, pure heat. And then that starts to kind of start a vicious cycle in the atmosphere, when you get the soil getting really hot, it tends to heat the air even more, it builds up a bubble of hot air over that dry, hot soil. And that tends to drive the jet stream even farther northward, it creates what has been called a heat dome. These heat domes are really formed by that extra warming that's happening at the surface and basically building a bubble of hot air over that region which also tends to steer any storms that might come in up to the north and away from that area so that it tends to make the dry hot conditions last a lot longer. And that's kind of what we've been seeing. The patterns in the upper atmosphere have been tending to steer the storms away from California. And that just kind of builds on itself after a while. And fortunately, that cycle has broken, at least temporarily and the reservoirs are getting filled. But yes, this is a very severe, widespread, extreme drought that has been affecting many of the western states and there's really no human precedent for it.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Francis is a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Thanks so much for taking time with us today.

FRANCIS: Happy to be here. Thank you, too.

Links

The Washington Post | “The Toll Extreme Weather Took in the U.S. During 2022, by the Numbers”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth