Black Hair Care Products & Toxic Exposure

Air Date: Week of February 17, 2023

Dr. James-Todd says that as black people resist pressures to conform to white standards of beauty, more have come to embrace their natural hair. (Photo: Nina Strehl, Unsplash)

Black women in America commonly use hair relaxers and leave-in conditioners to straighten and smooth their textured hair. But many of these products contain hormone-disrupting chemicals, which are associated with health problems such as early menarche, preterm birth, diabetes, and cancer. Dr. Tamarra James-Todd, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, spoke with Host Steve Curwood.

Transcript

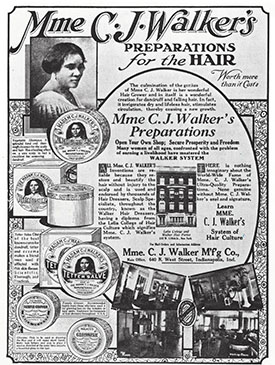

CURWOOD: In honor of black history month, we want to look back at one of the first African American women to become a self-made millionaire in the United States. Sarah Breedlove, better known by her married name Madam C.J. Walker, had 5 siblings and was the first one born in freedom in 1867, four years after the Emancipation Proclamation freed the rest of her family from slavery in the Confederate state of Louisiana. Madam walker went on to build a company that made hair care products especially for black women. She employed thousands of women to sell her products which were largely made of petroleum jelly, sulfur, beeswax, and violet extract for fragrance. Today black hair care products are a 2.5-billion-dollar global industry that includes, straighteners, relaxants, conditioners, gels, and foams. And according to a study by the Silent Spring Institute all of eighteen products they tested contained toxic chemicals that mimic estrogen in the body or disrupt the hormone system for women. So for a bit of our own history we dip into our archives. Here’s our 2018 interview with epidemiologist Tamarra James-Todd from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. We started our chat considering the tremendous diversity in the black community from skin color to types of hair.

JAMES-TODD: So, there are different textures and different grades of hair from relatively straight hair to very curly, sometimes called “kinky” hair, and they have different requirements. It's really dependent on the shape of the hair shaft, but that can cause people to need to use different types of products.

CURWOOD: And people often don't like the hair they have. If it's straight, they want it curly. If it's curly, they want it straight, huh?

JAMES-TODD: I think that would be universal for most women. [LAUGHS] Definitely. But certainly in the black community I think that there are some real issues around hair and part of that is kind of social and cultural issues regarding what is seen as beautiful, with straight long hair being kind of the stamp of beauty -- oftentimes in American culture particularly, in Western culture -- and so, people will do different things to try to adhere to that standard of beauty.

CURWOOD: So, what kinds of hair products do black women typically use?

JAMES-TODD: So, oftentimes when I'm asked this question and when I first started this line of work, the first thing that would come up is, oh, hair relaxers. And so, thinking about things that people use, you know, whether it's every few months or a couple of times a year to straighten their hair. But what I think is often forgotten is things that we use daily such as hair oils, moisturizers, lotions, leave-in conditioners, gels -- kind of, you name it, that's what people are using to get the different styles that they want.

CURWOOD: Or heat... I mean, as an African-American growing up, I saw women with these really hot combs and I have to laugh out loud at Alex Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X where he has this scene that Malcolm X tries to straighten his hair and his head is on fire so he sticks his head in a toilet to cool it down.

JAMES-TODD: Yes, that scene, I think, many, many women and some men can identify with... pressing, those pressing combs. So, it's not just chemicals, but it's also physical changes that people will try to do or undertake.

CURWOOD: So, what got you first interested in studying the potential health effects of chemicals in black women's hair?

JAMES-TODD: So, when I was a master’s student at Boston University, there was an interesting study of magazine advertisements advertised to white women versus black women. And there was a Ladies Home Journal article where it had an ad for white women being marketed to, kind of, anti-aging cream containing hormones. And the other magazine, which was kind of featured in this particular study, was from Essence magazine, a magazine commonly marketed and read by black women, and it was advertising placenta. And it was something that I remember seeing when I'd walk into, you know, a black hair supply or hair care store, and seeing placenta and just wondering, what exactly is that for? Why are people using that? And around that same time, an issue of Time magazine had come out, kind of querying why were girls starting their periods earlier and earlier. And somehow that just kind of clicked for me. Is it possible that what is in some of these hair products around hormones and so on… is that part of the reason why we're seeing earlier periods, particularly in black girls, which at the time there was a very large study that had reported that 60 percent of black girls had reached their periods by age 12 compared to only 30 percent or so of white girls. So, as a master’s student, that piqued my interest.

A 1917 Advertisement. Madam C. J. Walker, an entrepreneur and activist born in 1867, led the movement to create healthy hair care products designed specifically for black women. (Photo: Courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives/A'Lelia Bundles)

CURWOOD: And the answer is?

JAMES-TODD: So, we did, in fact, do a study; as a doctoral student at Columbia University, I did a study called the Greater New York Hair Products Study where we did, in fact, go and we queried what types of hair products people are using. And we found that young girls who were using hair oils for a longer period of time and more frequently had a significantly higher risk of starting their periods earlier than girls who had never used hair oils. And you know, each year earlier that a girl starts her period, it’s an increased risk for developing breast cancer.

CURWOOD: So, I'm thinking that this is linked somehow to chemicals -- fancy name is endocrine disrupters -- hormone disrupters, chemicals that kind of mimic estrogen and other hormones. To what extent is this phenomenon linked to such chemicals, do you think?

JAMES-TODD: So, at the time we started looking at this because of another study that had come out of the small case series of four young African-American girls. They ranged in age from four months old to four years old, and they had all developed breast and pubic hair. So, incredibly young children…

CURWOOD: ...at four months?

JAMES-TODD: At four months old!

CURWOOD: … at four months!

JAMES-TODD: ...and interestingly enough, the pediatric endocrinologist that had seen these young girls asked the moms all sorts of questions about what products they were using, what they had been exposed to in the home. And the common thread he was finding was that all of the moms were using -- these were girls so they were all using hair oils and different types of care products on children. Quite frankly, this is something that happens probably daily in the black community. But when he sent those products out for independent laboratory testing, he found three different forms of estrogen. And so when we started looking at this, and thinking about, you know, are these endocrine disrupting chemicals? -- I wasn't even there yet -- I was just thinking, maybe we'll find estrogen in these products. He, in fact, did and when he told the moms to stop using these products, the breasts regressed and the pubic hair fell out. So, fascinating case series. And when we sent these products out roughly 10 years later, we did not find those three different forms of estrogen. But we did find parabens, phthalates, and other chemicals that are known to be endocrine disruptors. And so what we know now is that about 50 percent of products advertised to black women contain these types of chemicals compared to maybe only seven percent that are advertised white women.

CURWOOD: You mentioned earlier periods. What are some of the health problems that have been linked to endocrine-disrupting chemicals?

JAMES-TODD: So, many of these products contain fragrance, which often is synonymous with phthalates. Phthalates are linked to obesity, increased risk of diabetes, as well as an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk, as well as pre-term birth and preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. There's some emerging work around fibroids that are showing some associations with some of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals and certainly there's some associations between some of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals and breast cancer and other cancers. There's a recent study, in fact, that came out looking at hair dyes and found associations with breast cancer incidence.

CURWOOD: So, how commonly do black women suffer from these various health problems as opposed to the general population?

JAMES-TODD: So, when you're talking about things like diabetes, aside from Native Americans, black women have the highest prevalence of diabetes in the U.S., for example. They are also more likely to be overweight or obese. They have some of the highest proportion of pre-term birth and a host of other things, fibroids and so on. And so when you're thinking about a lot of these metabolic or reproductive health outcomes, it's really important to consider why that might be occurring and not simply attribute it to, oh, there must be some inherent underlying genetic differences.

CURWOOD: Tamarra, what can consumers do to protect themselves from these potentially harmful chemicals and personal care products?

JAMES-TODD: You know, it's a two-part issue. Part of the problem is that our current laws which haven't changed since the 1930s particularly around personal care products, we don't require companies to disclose information regarding all of the substances they're putting in or chemicals they're putting into products due to trademark agreements.

Epidemiologist Tamara James-Todd spoke with Living on Earth about her research on the harmful effects of hair products on Black women’s health. (Photo: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

CURWOOD: Wait. So, what's in the stuff that's going on one's body is not on the label?

JAMES-TODD: Correct, and so, of concern, of course, is that then we're completely relying on the companies to test for the safety of our products. And it doesn't take a lot of thought, but that seems like a conflict of interest. The company is trying to make a profit. You know, right now, there is some legislation under way and being developed; the Personal Care Product and Safety Act is being developed by Senators Feinstein and Collins to really, kind of, rethink the protocol and the process by which chemicals and ingredients are tested before they make it to our shelves. Because the average consumer thinks that if it's on the shelf, it's safe.

CURWOOD: In the meantime, what's someone to do who says, OMG, this stuff could give me cancer or make me overweight, all kinds of not fun things. How can someone find safe hair care products?

JAMES-TODD: There is a growing amount of information out there around fragrance and considering going fragrance-free. So, that might be a strategy that one takes, maybe reducing the amount of synthetic chemicals that are being used. There's a kind of movement towards “do it yourself,” and then also, I think, you know, it's cultural change. So, we started with this idea of standard of beauty, and it’s, in my opinion, beautiful to see people starting to embrace more natural hair styles which require less chemical exposure. Certainly people are still using some of these other products daily, but the fewer chemicals that one might be using may be helpful.

CURWOOD: How affordable are paraben-free, phthalate-free alternatives to mainstream hair products for black women?

JAMES-TODD: So, I think the bigger question around that is, are they even on the market? There's very limited selection of those products on the market, and where they do exist they are often not necessarily in kind of traditional stores, and are often more expensive. So, in that case, I think that there needs to be more products introduced on the market, with recognition that these products are important to African-American women and that they do have purchasing power. This is a very large industry.

CURWOOD: We've been talking about women here, but of course, men use these hair care products. What risks do black men, do men of color, run when it comes to hair care products?

JAMES-TODD: It's funny you should ask that. One of the issues that came up when we were doing the Greater New York Hair Products Study that we did back in the early 2000s was that we were just collecting data on women. And one of our largest catchment areas when we were doing recruitment was at churches, and so we would go in and make our little pitch and I'll never forget, one gentleman and his son stood up and said, "What about us? We use hair products as well!" And I said, “Well, we're not really studying you right now." We were interested in breast cancer at the time which was part of the reason why we weren't studying men -- not that men can't have breast cancer! -- but it was one of those things where it was kind of an “ah-ha” moment and so the reality is that black men are using these products too. Oftentimes they wear shorter hair styles and so if you think about it, the application of some of these products is that much more close to the scalp and absorbed through the scalp, and, you know, could have some similar health implications for diseases that are linked to some of these endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about your own hairstyle, Dr. James-Todd, and what you use and what advice based on your own experience -- just anecdotally -- what advice you would make based on that experience.

JAMES-TODD: So, I remember when I was probably about eight or nine years old, and my mom took me to that, you know, beauty salon and I very much remember one of my first visits there. And again this is at a time period and an era where straight hair was what was acceptable, and so I had a perm done. And all my hair fell out. [LAUGHS] And I was done. I didn't want to do that anymore, and so I have been natural since the late 80s. And I remember that that was at a time where my grandmother, who was born in Tennessee, did not think that was acceptable at all. And I like my curly hair, and so it's been interesting to watch this transition happen before my eyes. I went to school in the south, too, I went to Vanderbilt University, and I remember many of the other black women thinking, like, why would she wear her hair like that, or thinking I was from a different country, because if I was American, I would not wear my hair this way. And it's been beautiful to see people embracing their hair. I am fragrance-free. I've been using the same product now for the past 30-plus years. Thank goodness it's still on the market! [LAUGHS] But, you know, I have a daughter as well and I use that same product on her. I think that minimizing -- again, my philosophy is if I can minimize the amount of products and maintain natural hair that's healthy, then that's good enough for me. As far as advocating for other women, I understand that some people don't feel as comfortable, you know, doing that, or they think that it'll affect their job or other issues. But I think as society changes its standards of beauty, it's been nice to see that being embraced.

For many in the black community, hair care is a process that may involve different products like leave-in conditioners, root stimulators and anti-frizz polishers – but it’s also an important community activity. (Photo: Andrew Ruiz, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Now people can go on our website to see your beautiful hair, but if they can't, it's lustrous, shiny, pulled back in a bun in the back. You must use a fair amount of oil.

JAMES-TODD: So, I do use this, it’s really a leave-in conditioner, and water. [LAUGHS] So, that's about it for me. But I do recognize that that's not what everyone else could do.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Dr. Tamarra James-Todd is an epidemiologist with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JAMES-TODD: Thank you.

CURWOOD: That segment was originally broadcast in 2018. The Personal Care Products Safety Act originally proposed by Senators Diane Feinstein and Susan Collins in 2015 was finally enacted by the Congress in the 2022 Omnibus Bill.

Links

The Greater New York Hair Care Products Study

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth