Greenwashing Energy from Plastic

Air Date: Week of March 24, 2023

Industry proponents of so-called “chemical recycling” claim that it offers a solution to difficult-to-recycle plastics, but it often doesn’t involve actual recycling at all. (Photo: Tony Alter, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

So-called “chemical recycling” is a greenwashing term used for incinerating plastic, according to critics including Veena Singla with the Natural Resources Defense Council. She tells Host Jenni Doering that “chemical recycling” is contributing to climate change and poor air quality for many marginalized communities.

Transcript

DOERING: Any type of recycling seems like a win for the environment, part of the green holy trinity of “reduce, reuse, recycle.” But not all recycling is created equal. So called “chemical recycling” of plastic waste often doesn’t actually recycle at all. Skeptics say it usually amounts to greenwashing for waste incineration which creates a health hazard for communities near incineration facilities. Nonetheless, chemical recycling plants are popping up across the country claiming to be part of the solution to our plastic waste crisis. For more I spoke with Veena Singla, a Senior Scientist for the Natural Resources Defense Council. She says that along with “chemical recycling”, the industry has come up with other terms to greenwash this polluting industry.

SINGLA: I've heard a whole host of creative names. I think my favorite is plastics renewal, which sounds like plastics are going to a spa and getting facials?

DOERING: Yeah. Sounds nice. How is chemical recycling different from normal recycling.

SINGLA: The way plastic that gets recycled today, if it does get recycled, is by mechanical recycling. Mechanical recycling is different from these chemical recycling technologies. In that it's pretty simple. The plastic is cleaned, and shredded up, and then that can be turned into new plastic products. So it's pretty straightforward. That's what's happening today, we all know that most plastic unfortunately does not get recycled. But the amount that does get recycled, it's mechanical recycling, that's doing the job. And we know that it does work for certain kinds of plastic. Now chemical recycling, it's a lot more complicated. So you still have the same first part of that process of, you know, putting the plastic in your bin. It gets sorted. It gets sent to the facility, but then many different things can happen. It might be turned into fuel; it might be turned into new plastic; it might be turned into chemicals. So there's many more steps in the so called chemical recycling than mechanical recycling.

DOERING: So you say this is not actually recycling? Can you explain that for me? I mean, I understand that there's different processes involved. But if a company says that they're taking this plastic, and they're gonna turn it into some new, wonderful plastic, what does that mean? And what does that not mean?

SINGLA: So recycling is when you're taking waste, putting it back into new products, it's reducing the demand for virgin resources and making new plastic. That's why recycling is a good thing. Now, some of these chemical recycling technologies or processes, what comes out the other end is not used to make new plastic or make new plastic products. That's why I say it's fake recycling sometimes, because it's used as a fuel. It's burned for energy. And that's energy recovery. It's not recycling, and you don't get the benefits of recycling of closing that loop, and reducing the demand for resources to make new plastic.

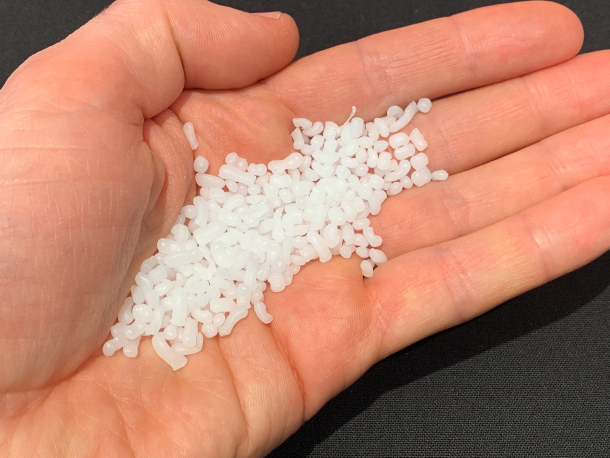

Plastic nurdles are tiny pieces of plastic that constitute the primary feedstock of plastic manufacturing. So-called “chemical recycling” claims to be able to turn post-consumer plastic waste back into this virgin plastic building block. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr CC0 1.0)

DOERING: Right, that sounds a lot more like what we're already doing with a lot of our plastic wastes now is sending it either to landfills or actually incinerating it. And, you know, sometimes incinerators do capture some of that as energy when they burn it. But it's essentially just taking this waste, not having to stick it in the landfill.

SINGLA: That's exactly right, these chemical recycling processes that are creating fuels, it's like delayed incineration. It's just another kind of incineration, where the plastic is taken in and, using high heat and pressure, it's broken down and turned into these fuels. But it's eventually burned. So it has all the same issues as incineration, and that when you burn the fuels, you're creating harmful greenhouse gases and air pollution.

DOERING: What are some of the chemicals that are emitted from these so called chemical recycling, maybe we could call them fake recycling, as you said, from these plants?

SINGLA: Yes. What we found when we went to look at the so called chemical recycling facilities in the US is, one there's a lack of transparency and information publicly available about these facilities, what processes they're using, what chemicals they're using, and what their emissions actually are. We were able to find some information from EPA databases, the Environmental Protection Agency databases, and state permit information. What we found across the board is that these facilities are allowed to admit a variety of harmful air pollution, air pollution, like particulate matter that is harmful to people's lungs and heart health. toxic air pollutants like heavy metals, lead, other chemicals like benzene that are known cancer causing chemicals and they're harmful to the developing fetus. We found that these facilities were allowed to release this air pollution based on their state air permit data. We also found that a number of these facilities are generating large quantities of hazardous waste. So, one facility in Oregon created almost 500,000 pounds of hazardous waste in one year alone.

In a 2018 protest, concerned citizens took to the water to let petrochemical executives at the David L. Lawrence convention center in Pittsburgh know that they do not want to become the next “Cancer Alley.” (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: And where are some of these so-called chemical recycling, or these fake recycling plants located and what are the communities that surround them?

SINGLA: We found these so-called chemical recycling facilities in states across the US, some on the West Coast, some in the South, some in the Midwest, but what they had in common is they're located in communities that are disproportionately low income, or people of color, or both. And this was seven out of eight of the facilities that we looked at. They're being cited in communities that are historically and currently marginalized and generally burdened by more sources of environmental pollution and social stressors. This raises major environmental justice concerns.

DOERING: What about regulation from the Environmental Protection Agency, you know, what proposals would companies have to go through in order to actually get one of these plants built?

SINGLA: So some of these chemical recycling technologies are currently subject to Clean Air Act regulation. And the specific technologies in question are called pyrolysis and gasification. And these are not new technologies. They've been around for decades, many years. And they're classified as incineration under the Clean Air Act because they use high heat and pressure to break down inputs, whatever kind of wasted is whether it's plastic or something else, and burn a lot of those inputs to power the process. It takes a lot of energy. And these are the same processes that we are seeing are used to turn plastic to fuel, so that fake recycling. And what has happened is that there was a proposal in the previous administration to change this Clean Air Act regulation, and no longer call a pyrolysis and gasification, these specific kinds of chemical recycling, no longer call them incineration, basically exempt them from the Clean Air Act. And this is a major concern. These technologies need to be regulated under the Clean Air Act. We're seeing, as I mentioned, that these facilities do release harmful air pollution. And the Clean Air Act helps impose common sense safeguards to limit such pollution. And we've been pushing the current administration to withdraw that proposal. It, unfortunately, hasn't happened yet.

Only around 5% of plastic in the United States gets recycled and the rest is incinerated, landfilled or ends up polluting the environment. (Photo: Dan Keck, Flickr CCO 1.0)

DOERING: So just to be clear, that proposal was put in place under the previous administration, the Trump administration and now, Biden administration has not yet revoked that.

SINGLA: That is correct. One important thing to note here is that the plastics industry has been successful in changing state laws to ease the way for these so-called chemical recycling facilities. And what they've done is made these facilities subject to less safeguards and regulation than they otherwise would have been. And we're seeing proposals for new facilities in the states where these laws have passed.

DOERING: So you mentioned it takes a lot of energy to turn old plastic waste into new materials or fuel. What's the carbon footprint of chemical recycling plants?

Veena Singla is a Senior Scientist for the NRDC’s Peoples and Communities Program. (Photo: courtesy of NRDC)

SINGLA: This is a great question. And what we're seeing is that some of these chemical recycling technologies have enormous carbon footprints. So for the two I mentioned, specifically pyrolysis and gasification, that are considered incineration, there was a recent study out from Department of Energy authors that found that pyrolysis and gasification used about 10 to 100 times more resources and had about 10 to 100 times more impact compared to mechanical recycling, that traditional kind of recycling. So it's really having major pollution and carbon footprint impacts.

DOERING: Veena Singla is a senior scientist for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thank you so much. Veena.

SINGLA: Thank you, Jenni. It's been a pleasure

DOERING: We reached out to the Product Stewardship Institute, a policy advocate and consulting nonprofit*, for a statement. CEO Scott Cassel responded in part:

Chemical recycling is a term that encompasses many technologies, one of which is pyrolysis, which typically produces fuel. Our state and local government members consider pyrolysis as disposal. They don’t want to burn more materials; they want to return them to the circular economy.

To read their full statement go to the Living on Earth Website, loe dot org.

*Editors Note: A previous version of this transcript incorrectly called PSI an industry Association.

Links

NRDC “Recycling Lies: “Chemical Recycling” of Plastic Is Just Greenwashing Incineration”

Beyond Plastics “Is Chemical Recycling Greenwashing?”

NPR “Recycling plastic is practically impossible — and the problem is getting worse”

Statement from Product Stewardship Institute on Chemical Recycling

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth