Mapping the Seafloor to Predict Coastal Flooding

Air Date: Week of March 24, 2023

USF Oceanographers follow an uncrewed autonomous vessel. The vehicle is helping create hyper-detailed maps of the seafloor just off the coast. (Image: David Levin)

The topography of the coastal seafloor has a lot to do with how much flooding coastal areas will experience during hurricanes. As reporter David Levin reports, a team of scientists is working on a new technology to create more accurate seafloor maps in the Gulf of Mexico.

Transcript

DOERING: The Gulf Coast of the US is often in the crosshairs of huge storms and hurricanes but the damage from those storms can vary dramatically from place to place. In September of 2022, for instance, Hurricane Ian pushed more than 7 feet of water into Fort Myers, Florida but just a few miles north Tampa weathered the storm with minimal damage. The topography of the ocean floor has a lot to do with how storm surge affects coastal areas, but it can be tricky to accurately map that part of the ocean. Now a team of scientists is taking up the challenge. Reporter David Levin has been digging into the new technologies being used and has this story.

MALLOY: Let's go. Fuel pumps on, lights on.

LEVIN: At a small airport in St. Petersburg, Florida Pilot Greg Malloy runs through his checklist. He's getting ready to fly over the nearby beaches with a device called LIDAR fixed to the belly of the plane. It's short for laser detection and ranging, and it'll make a continuous 3d scan of the coast and the ocean floor nearby, providing a map of its contours.

MALLOY: Clear prop [not sure] [Engine noise] back engage.

LEVIN: Malloy is working with the Center for Ocean Mapping and Innovative Technologies are COMIT a group of researchers at the University of South Florida who are developing quicker, more efficient and more timely ways of charting offshore waters. Having accurate maps of the seafloor is critical for shipping, transportation, fishing, disaster response, but the problem is no single technology can give you the information you need for a detailed map. Satellites can't see the bottom of the water's murky and research ships can't navigate the shallows. Even Greg Malloy's his aircraft has limits, it can scan hundreds of miles of coastline in a single pass but if the water is too deep or too cloudy, it can't sense and map the seafloor. COMIT is trying a different approach. They want to combine lots of technologies all at once to create a super detailed map. It's a technique called a nested survey.

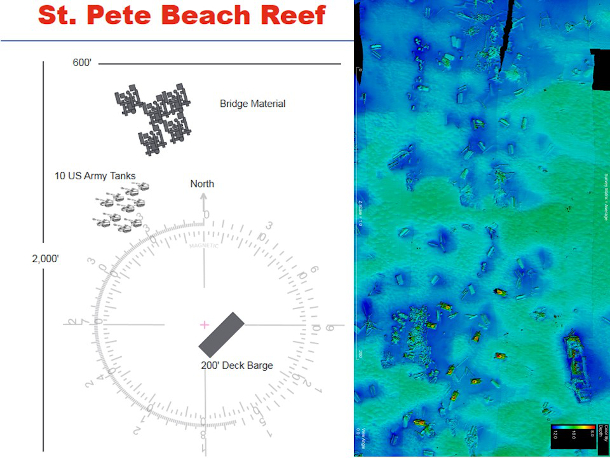

(On left): level of detail available on existing maps of shallow water near Florida’s St. Pete beach. (On right): hyper-detailed sonar images that USF is creating of the same area. (Image: USF College of Marine Science)

MALLOY: And so what we're doing is trying to fill in the gaps that one technology has with the strengths of another technology.

LEVIN: Steve Murawski is an oceanographer at the University of South Florida.

MURAWSKI: And also, I'm the director of the Center for Ocean Mapping and Innovative Technologies.

LEVIN: Today, he and the COMIT team are trying this nested approach for the first time. They're pulling data from satellites, airborne LIDAR, and a new high-Tech system [SFX]. In a cluttered workshop on the other side of St. Petersburg, the COMIT team is testing an electric motor, on a vehicle that looks like a huge stand up paddleboard. It's sixteen feet long, four feet wide, and it's got a bright yellow tarp covered in solar panels. It goes by a few different names.

HERMAN: An uncrewed surface vessel is sort of the most common term, drone is nice because it's not quite so many syllables and I call it a boat because everybody knows what a boat is.

LEVIN: Jigger Herman is co owner of SeaTrack the company that built this robotic boat. Both he and Murawski think that machines like this one could be essential for collecting intricate maps of the coast in the future. They're nimble, they're autonomous, and they can go places most other vehicles can't.

HERMAN: Our boat is nice in that it's well suited to very shallow water.

LEVIN: That means it can get into every coastal nook and cranny. And with its sensitive onboard sonar, it can record the bottom in incredible detail, filling in any gaps on LIDAR maps made by aircraft. But first Herman needs to tell the boat where to go.

The miniature sonar device aboard SeaTrac's uncrewed vehicle can pick up minute details in shallow water—like the ghostly outline of a manatee, seen here. (Image: David Levin)

HERMAN: It's going to be doing the northbound line, it's doing that first line right in front of you.

LEVIN: In a nearby classroom, the COMIT team has built a makeshift control room. Two huge flat screen TVs take up the entire wall showing maps, GPS coordinates and live feeds from a boat sonar device. Herman sits nearby surrounded by six more monitors. Four of them display live video feeds from the boat and the other two shows software he uses to program its path through the water.

HERMAN: I can see all the health and all the status of what the boats doing, how fast it's going, where it's headed and then from here, I can load new missions and change the mission depending on what the survey requirements are.

LEVIN: The team is also sending a small chase boat behind the robot to make sure things go smoothly and to keep bystanders from getting too close.

[SEAGULLS SFX]

LEVIN: A few miles from the airport I'm standing at the edge of a wide channel flanked by thick mangroves. Flocks of pelicans and seagulls hover nearby is the team on loads the yellow survey boat from its trailer. Steve Murawski is sitting on an inflatable zodiac next to the dock. As the robotic boat sets off, he put his clothes behind it keeping an eye on its progress and sure enough, it attracts plenty of curious onlookers.

You know, it's a beautiful day a bunch of people out recreational boating there's a couple of kayakers that are you know are in the channel and the robot is about ready to go swimming by them, that'll freak him out right [LAUGH].

Murawski says he doesn't mind answering a few questions about the survey. After all, he's got plenty of his own about the seafloor. As we round a bend in the channel, it's easy to understand why. The waters quickly go from a crystal clear to an opaque blue and the bottom just disappears to the naked eye. Despite being only a few miles from Tampa details about the seafloor here are pretty sparse. So you think it's never been mapped in detail?

MURAWSKI: Not in detail, no, no way. This is a first timer. You know it's too shallow for the normal surface craft and too murky for aircraft and so yeah. we're blazing a new new trail here.

In a makeshift control room on the USF campus, scientists watch sonar and video data arrive in real-time from an autonomous uncrewed vehicle. (Image: David Levin)

LEVIN: This is exactly the sort of place where sea tracks robotic boat is meant to shine. Although it's hard to tell from the surface, the bottom here rises and falls dramatically forming underwater hills of sand and sediment and shifting currents can actually push those hills around, leaving them in unexpected places. I'm sitting in the bow of the chase boat and we're surrounded by sandbars just under the surface of the water. You can see the waves breaking over them and they extend maybe a half a mile offshore. In rough weather, these things would be pretty dangerous for boats.

WEISBERG: I like to say anybody with a sailboat on the West coast of Florida, if they ever tell you that they never ran aground they're either lying or they've used their boat, because there's so many shores that no matter how careful you are, at some point you're gonna rub up against the bottom.

LEVIN: Bob Weisberg says that even on a good day, shifting sandbars can be a big problem for navigation. He's a physical oceanographer with Herman and is working on how to determine where sediments go after a storm. In addition to stranding boats, unexpected changes in the bottom could create issues back on shore. If large amounts of sediment move around during a hurricane Weisburg says it could steer more water inland at specific pinch points. Based on information collected by Coleman he's building a powerful computer model that can tell which areas might be in danger when the next big storm hits.

Engineer Jigger Herman programs the autonomous vessel’s course remotely from USF’s control room. Using a live video feed from the boat, he can take control manually at any time. (Image: David Levin)

WEISBERG: So the way the water depth varies from offshore to the coastline is a very important factor and the height of the water at any location during a hurricane storm surge. The shallower the water the higher the surge.

LEVIN: He'll have plenty of data to sort through between airborne LIDAR and sonar data from SeaTracks. robotic boat, the team is collecting a huge amount of new information.

HOMYER: I'm gonna give you a down and back one more. Yep, I gotta make this I gotta make the down.

LEVIN: Back in the control room, Matt Hommyer is sitting right next to Jigger Herman watching the boat’s sonar feed as it comes in real time. It can instantly track where the vehicle has been and what's left to explore.

HOMMEYER: Basically, we've got some we've got some gaps here and they're in really important places because this is one of the main areas where water gets from A to B between the Gulf of Mexico and Tampa Bay.

LEVIN: Hommeyer is a Technical Operations Manager with COMIT and he's their resident mapping specialist. As soon as he gets data from the robotic boat, he can render it into a stunning and incredibly accurate 3D map of the seafloor. What are we looking at over here by the way?

HOMMEYER: So that's a barge right there. The barge is about 200 feet long. We got a little shipwreck here 50, 60 feet long.

LEVIN: As he zooms in on each of these features, tiny details start to appear. The stout walls of the barge, the curving bow of the shipwreck.

After a long day of logging data, engineer Hobie Boeschenstein begins to pull the autonomous uncrewed vessel back out of the water. (Image: David Levin)

HOMMEYER: So that's your 3D point, there's a very boat look and shape. [LAUGH]

LEVIN: Data from the boat sonar is so detailed, it even picks up the ghostly image of animals swimming underneath it.

MULTIPLE SCIENTISTS: Oh my God, that is so cool! Looks like a manatee.

LEVIN: COMITS main goal was getting this level of detail about the bottom quickly and efficiently. Given their technique speed and its relative low cost compared to other methods, it could eventually become the norm and ocean mapping and in the process provide a much better picture of the ocean as a whole. Again, Matt Hommeyer.

HOMMEYER: Getting more eyes and ears on the ocean more often is going to really expand our understanding of this system, that's just hopelessly complex. The more we can fill in those gaps with actual information and measurements rather than educated guesswork, I think is really going to advance our understanding of the resources and the ecosystems and everything that we care about.

LEVIN: With the work that COMIT team is doing, scientists could answer some long-standing questions about the coastal sea floor while helping protect the people who live there. If seafloor maps like these get easier and cheaper to create that could have an impact not just in Florida, but in coastal regions worldwide.

DOERING: Reporter David Levin’s story was made possible with a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Links

COMIT, the Center for Ocean Mapping and Innovative Technologies

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth