Rocks from Another (Little) World

Air Date: Week of October 6, 2023

The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is launched via a United Launch Alliance Atlas V 411 Rocket on September 8, 2016. (Photo: United Launch Alliance, Courtesy of AsteroidMission.org)

The spacecraft OSIRIS-REx has successfully delivered a sample from the asteroid Bennu to Earth. Scientists like Dr. Vicky Hamilton, a planetary geologist and co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx mission, are eager to study the rocky material and see if it can unveil anything about the origins of our solar system. Dr. Hamilton joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share surprising findings from the mission.

Transcript

O’NEILL: On September 24, the spacecraft OSIRIS-REx flung a capsule with precious cargo back to Earth. It contained bits of surface material taken from the asteroid Bennu, making it the first U.S mission to bring an asteroid sample home. The OSIRIS-REx spacecraft launched in 2016 and collected its sample from Bennu in 2020. Dr. Vicky Hamilton is a planetary geologist at Southwest Research Institute in Boulder Colorado, and a Co-Investigator on the OSIRIS REx Mission. I asked her why scientists are so eager to get their hands on these rocks.

HAMILTON: The goal of the mission is to return a pristine sample of a carbonaceous asteroid. And what that means simply is an asteroid that has a large amount of carbon on it. And the whole point of this is because meteorites from these asteroids exist, but they're contaminated when they fall to Earth, they pass through our atmosphere, they interact with our biosphere and our hydrosphere, and that changes them and it changes their chemistry. And so by going and collecting a pristine sample of one of these asteroids, we can take it into the laboratory and look at it and study it without all those interferences from our own planet.

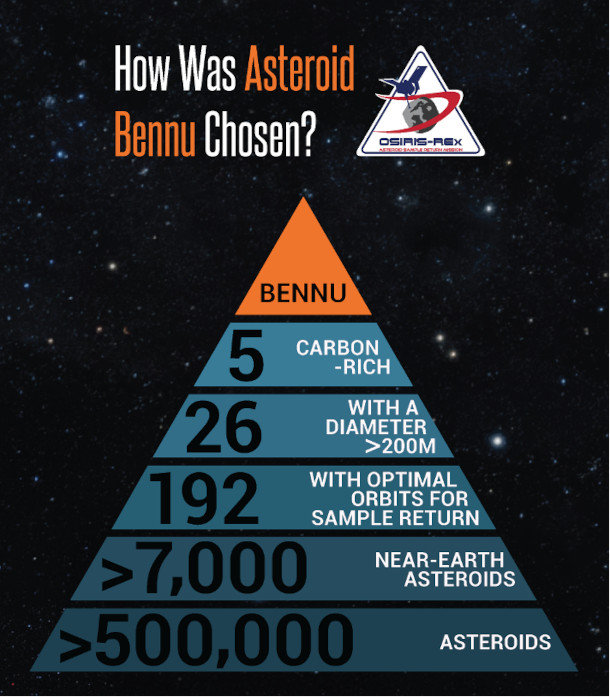

O'NEILL: And how did the asteroid Bennu get selected? What were you looking for, that makes it the ideal asteroid to go after.

HAMILTON: Any asteroid that we would visit needed to meet a series of criteria, it needed to be in an earth crossing orbit, because one of the other goals of the mission is to understand potentially hazardous asteroids, it needed to be in a location and with an orbit that we could easily send a spacecraft to and return to Earth. Most NASA missions don't need to come back. But this one did. So we needed an orbit that was favorable for that, we needed an object that was big enough to operate around with a spacecraft. And we needed it to be a carbon bearing asteroid. And so by the time you kind of put all of the criteria together, we came to a list of about five different asteroids and Bennu ended up being our pick.

Bennu was one of very few asteroids that met the criteria for the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission. (Photo: University of Arizona, Courtesy of AsteroidMission.org)

O'NEILL: And tell us a little bit about the Bennu asteroid itself.

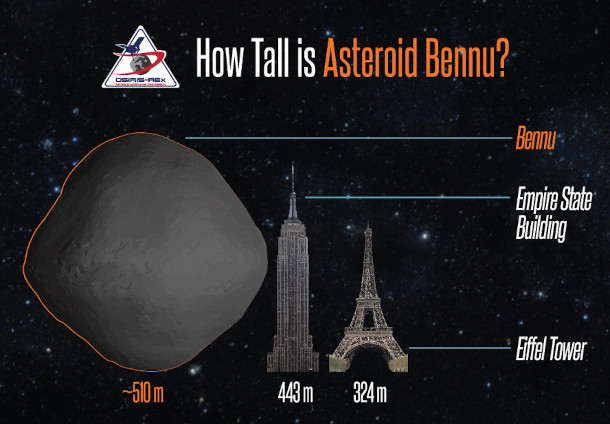

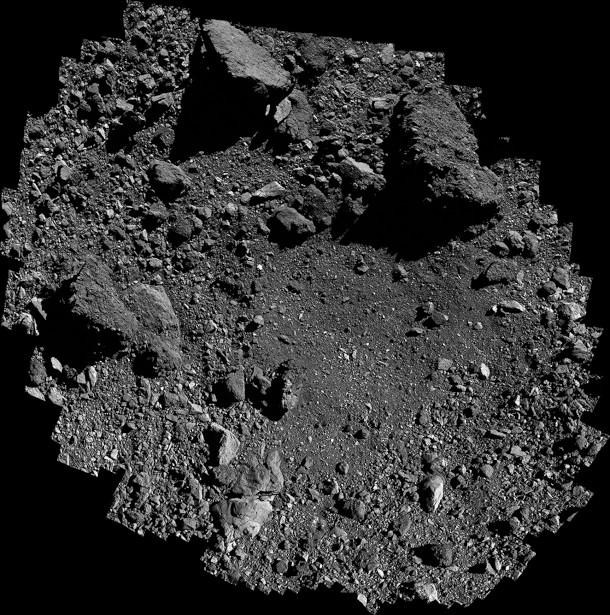

HAMILTON: So Bennu is a modestly sized asteroid. It's about 500 meters across, about the size, roughly, of the Empire State Building for folks in the US. And then one of the things that was most interesting was that we didn't know for sure what the surface was going to be like when we contacted it with our spacecraft. So we didn't land on Bennu, we had an arm that stretched out. And we just basically touched the asteroid and then backed away. And it turned out that we sank into the surface more than we expected. And so people have described it being like a ball pit. You know, you go look at this thing that looks like it has a surface, but you jump into it, and you sink way deeper in than you thought you would. And the surface of Bennu was a little bit like that.

O'NEILL: What is it that we are able to learn from asteroids?

HAMILTON: Asteroids are fascinating because they record a part of our solar system's history that is no longer present on the earth. Asteroids are little frozen bits of things that didn't get incorporated into the planets. And they were effectively frozen in time back 4.5-6 billion years ago. And they record the processes that were going on at that time. And so we can use them as literal time capsules. To investigate the processes that were happening as our sun and our solar system, were forming. The carbonaceous asteroids in particular, tell us something about organics and about water, both of which are obviously very important to life on Earth. And so we're hoping to get a glimpse into that past history, where this inventory of chemistry came from what it looked like at the very outset.

Asteroid Bennu is roughly as tall as the Empire State Building. (Photo: University of Arizona, Courtesy of AsteroidMission.org)

O'NEILL: So I want to hear a bit more about what it must have felt like to have that successful return September 24 2023. What was the energy like from you know, the planetary geologists of the world and now that the sample has been safely brought back?

HAMILTON: Oh, it's, it's really exciting. I mean, the event itself is both this mixture of excitement and terror, because you're watching that capsule, you know, enter the Earth's atmosphere, you're you know that it's been released, you know, it's coming back. But you're just biting your nails until you see that parachute deploy. And then when we saw the first pictures of how the capsule had landed in Utah, it was gorgeous. It could not have been any more perfect. I think everybody's just thrilled.

O'NEILL: So I'd like to hear a little bit about the sample that was collected. Did it in fact, arrive in that pristine condition? Have you gotten to look at it? What's it like?

HAMILTON: So the sample canister was taken from its landing spot in the desert into a cleanroom, a temporary cleanroom. And then the very next day, it was flown here to Johnson Space Center in Houston and put into a glove box and for the last week, the curatorial staff here has been very carefully, very methodically, opening things up progressively. Now we have not yet gotten into the innermost part of the sample canister, there's an outer cover. And we opened that up last week. And we got our first look at some sample anyway, which was really exciting because there was some very small particles and sort of large sand grain size, millimeter sized particles sitting outside the sample canister. And so we've actually got a team of people there called our quick look team. And we've handed off some of those particles to them. And they've been off doing some early preliminary analyses. But I think everybody's really waiting and excited to get into the innermost sample canister, because that's where we're hoping that we've still got some sort of bigger chunks, some, some small stones that we'll be able to look at. But the science team is just really excited, we're going to start allocating pieces of the sample to our science team members around the world, just as soon as we can and start really going to work on the science.

The image above is a mosaic of images obtained by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. It shows the sample site Nightingale on asteroid Bennu. (Photo: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona, Courtesy of AsteroidMission.org)

O'NEILL: How is it going to be distributed to you know, interested parties, who gets a chance to look at it?

HAMILTON: So the sample gets distributed by in part international agreements, part of it actually goes into long term storage for future generations. In fact, the majority of the sample will be put under seal, and protected so that decades or even hundreds of years from now, future scientists will be able to look at the sample, measure it with instruments we haven't even invented yet. But for today, the science team of the OSIRIS REx mission gets about 25% of the return sample, so that we can complete our promise to NASA to perform the science that we said we would do, about 4% of the sample will go to the Canadian Space Agency, who contributed one of the scientific instruments to the mission, about half a percent of the sample will go to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA. And then lastly, the scientific community will be able to request pieces of Bennu for their own research, starting about six months from now. And so that's a process where scientists like me can write a proposal and say they want a piece of Bennu and what they're going to do with it, and what science they want to study. And then the pieces will be allocated for that purpose. So it becomes available to lots of people now, but also future generations.

O'NEILL: And now it's been sort of a wild journey from the launch in 2016. A sort of picture perfect landing, just you know, just this year, I just want to know, how are you feeling about all this? And what are you looking forward to? Now that we've got this on Earth?

The OSIRIS-REx mission team receives news that the sample return capsule was closed successfully on October 28, 2020. (Photo: Lockheed Martin, Courtesy of AsteroidMission.org)

HAMILTON: I'm still very excited. We all are, we can't believe that we're finally at this point. You know, it's this proposal for this mission was submitted to NASA in 2010. So you know, some of us have been working on it. Since then, some people were working on even the predecessor version of this mission. So for all of us, it's just really exciting to actually be at this moment. For me, the next big thing is when I'm able to get sample and take it back into my lab in Boulder, and start to analyze it and just see what's in there. I mean, I just can't wait to see what's in there, and then be able to compare it to other meteorites that we know about and compare to the predictions we made about what it would look like based on the data that we collected at Bennu.

O'NEILL: Dr. Vickie Hamilton is a co investigator on the OSIRIS REx mission. Dr. Hamilton, thank you so much for joining us today.

HAMILTON: Thank you so much for having me.

Links

OSIRIS REx – The University of Arizona | “Asteroid Operations”

University of Arizona | “OSIRIS-REx”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth