Warming Supercharges Hurricane Otis

Air Date: Week of November 3, 2023

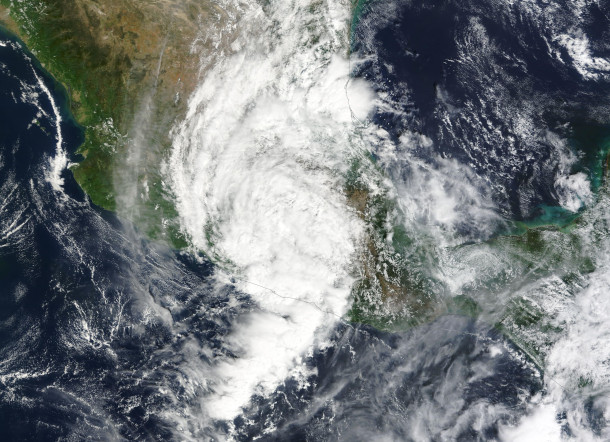

Hurricane Otis continued its explosive intensification episode off the coast of Guerrero during the evening of October 24th. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons)

Exceptionally warm waters in the Eastern North Pacific off Acapulco, Mexico fed the rapid strengthening of Hurricane Otis into a deadly Category 5 storm that weather forecasters failed to understand in time to warn the public. MIT Professor of Atmospheric Science Kerry Emanuel joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the science behind the storm and share how needed improvements in weather forecasting can help communities better prepare for extreme storms.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Weather forecasting has always been a gamble, but climate disruption has drastically worsened the odds for accuracy. Forecasters recently missed the explosion of Hurricane Otis, which in just 12 hours became a category five storm that left nearly a hundred people dead or missing. Scientists believe that exceptionally warm waters in the Eastern North Pacific off Acapulco Mexico fed this hurricane’s rapid development. Here to explain and consider ways of improving extreme weather forecasting is Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kerry Emanuel. Welcome back to Living on Earth Kerry!

EMANUEL: Well, it's great to be back with you.

CURWOOD: Now, by the way, you're familiar with the area of Acapulco, where the storm came ashore. I gather from your research.

EMANUEL: Well, about 30 years ago, a colleague of mine and I ran a field project out of Acapulco called the tropical experiment in Mexico, aka Tex Mex. Where are we were trying to understand the physics underlying the genesis of tropical cyclones by flying into them with research aircraft, making all kinds of measurements. So yes, I was familiar with it 30 years ago,

CURWOOD: I imagine back then, though, you didn't run into a storm like this.

EMANUEL: Not like this one. In fact, I don't think anyone's run into a storm like this one, with the possible exception of Patricia, back in 2015, also in the same general region.

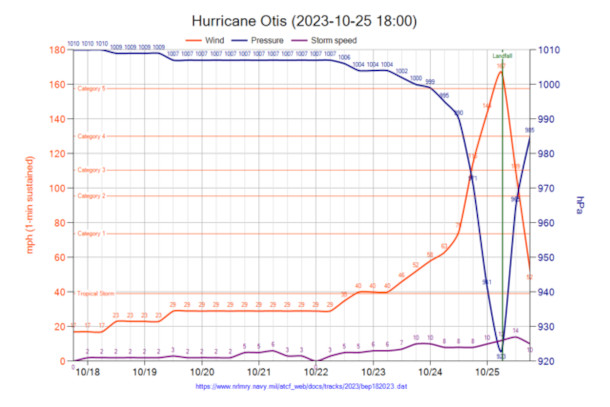

CURWOOD: Now, as you point out, this is a forecasters nightmare. I mean, people originally, were told that this might be a category one storm to come ashore, they're at Acapulco, and then 12 hours later, suddenly, they're talking about a category five hurricane with winds of over 160-165 miles an hour. What do you make of that?

EMANUEL: It's hard to imagine anything worse. And this is something that we drilled ourselves on, the worst case scenario is figuratively going to bed with a tropical storm with no indication in the forecast, that would be much stronger, and waking up the next morning, and it's a cat four, although in this case, it was actually worse than our test case. And not too many hours away from landfall, no time to warn anybody. It's really, really a worst case storm.

CURWOOD: Now, you've been cautious about linking big hurricanes to climate disruption from human activities. How do you think Otis might be related to that?

EMANUEL: Well, it's normally very, very difficult to say anything about the relationship between a particular storm and climate change, whether it's El Niño, something else, or global warming, we are much more comfortable looking at the statistics of storms. But we do know that there's a speed limit, it's imposed by thermodynamics that puts an upper bound and how intense a storm can get. And it puts an upper bound on its rate of intensification. And Otis was right at that limit. And the limit itself was very high because the water was so hot there. So I would go out on a limb and say a storm intensifying that fast was probably not physically possible 40 or 50 years ago.

Using data from the US Naval Research Laboratory, this graph shows the rapid increase in wind speed before and during Hurricane Otis. (Photo: Phoenix7777, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now, the ocean absorbs a lot, perhaps most of the excess heat from greenhouse gas emissions. And of course, the temperatures in the ocean are getting higher and higher. What are the physics of this warming and the intensity of hurricanes such as Hurricane Otis?

EMANUEL: So when you make the climate system warmer, it's possible to have hurricanes that are more intense, they're not necessarily more frequent. In fact, they may actually become a little less frequent. But this cap on their intensity goes up. What's really interesting for us, and so far kind of hard to predict, is the pattern of warming, it's very easy to fall into the trap of thinking that global warming is globally uniform, but it isn't. And the pattern of warming is much more influential in hurricanes, then the mean warming is. So for example, if the Atlantic warms up faster than the rest of the tropics, we would expect to see a large increase in activity there if that were the case. But we're not so very confident in our predictions of the pattern of global warming.

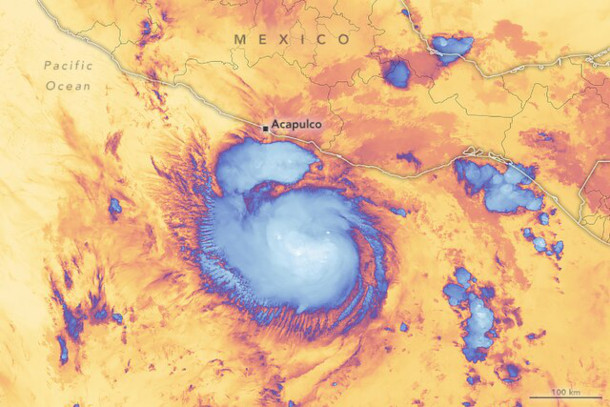

CURWOOD: So what if anything is special about the eastern Pacific tropical cyclones that we call hurricanes?

EMANUEL: Yeah, there's something very interesting about the Eastern North Pacific, the waters to the west of Central America and Mexico, and that is that they're much fresher at the surface than other parts of the tropics that are susceptible to hurricanes, that is there less saline. That's important because fresher water is also lighter it tends to like being at the surface. Normally, when a hurricane comes along, it turns up cold water from deeper down. And that limits its intensity. It's a very important effect, especially on strong storms. But in eastern Pacific, this salinity stratification, the fact you get saltier as you go down. And therefore heavier, tends to damp out that mixing. And we find in our models is to get reasonable statistics of intensity in eastern Pacific hurricane, we have to include that salinity effect. And that makes them stronger than they would otherwise be.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about how you scientists track hurricanes and how we can improve that science and technology.

Hurricane Otis rapidly developed from a category 1 to category 5 storm. This image depicts what the storm looked like at 2:30 am in the tourist town of Acapulco. (Photo: Michala Garrison, NASA Earth Observatory, Wikimedia Commons)

EMANUEL: Well, there are a lot of improvements that we can make. Certainly the first thing I would focus on is improving our understanding of the physics of storms. It's not just a question of technology. But having improved that understanding where they're better positioned to build better models, we should definitely be moving away from what we call a deterministic forecast — a single forecast of a track and of intensity — and move into the probabilistic world. Where are we, at a given time make 50 or 100, or 1000 forecasts, which differ only in slightly different, but equally probable realizations of the initial condition, or in different but equally plausible parameters in the model so that we can bound the probabilities of these and we should translate that, and this is the really tough part, is to translate that into a very concise, beautifully worded description for the public, and for emergency managers, and so forth, so that they are aware not only of what we think might happen, but also we think might possibly happen. It's so important in this case, we might have been able to say, yeah, there's an outside chance that's going to intensify rapidly if we had good models, and we were doing things probabilistically.

CURWOOD: Now, how do you deal with the psychology of that though, because if you say to a town, let's say resort town, like Acapulco, Mexico, that, you know, as a probable chance that something kind of grouchy could come through here, human nature is well, okay, but they only think it's likely or possible, I don't know, I'm gonna just, I'm just gonna keep going until I hear that it is or it isn't.

EMANUEL: It's much more important for people like emergency managers whose business it is to make decisions, for example, whether to evacuate or not, to have that good probabilistic information. For example, last year, there was Hurricane Ian, that affected Southwestern Florida and one of the towns had a rule it made for itself, that if the probability of there being more than a foot of water at a certain place in town was more than x percent, I don't remember what it was 30%, something like that, they would evacuate. So they had learned how to use probabilistic information to make decisions, you can't expect just a random member of the public necessarily to be thinking that way. But you know, we already do that you get on your smartphone, you want to know what the weather is going to be tomorrow, it says a 75% chance of rain, you get used to interpreting that. Okay, I'll take my umbrella. And of course, it's much more important when we're trying to forecast some kind of life-threatening weather like a hurricane.

CURWOOD: So what's to be done? In terms of dealing with hurricanes and the public? And the various risks? I mean, what steps can we take two make better predictions about what's going to happen with hurricanes in their intensities to protect the public health.

EMANUEL: But I think there's two things we scientists can do. First of all, we have to do a much better job projecting long term risk, and how that's changing as the climate changes so that people can make intelligent decisions about where they're going to live, what they're going to build, and so on, we need to move into this probabilistic world and make many many forecasts to bracket, the possibilities, and not just to say, well, this is our best shot and what's going to happen. We need better models, we need better computers, so that we can resolve the atmosphere better, we need to make better measurements of the ocean below the surface, that's really tough to do. You can see the surface temperature with satellites, but you need to know the temperature and salinity of the water down to 100 meters or so if you really want to make a good forecast of an intense hurricane. So there's all those things. And I would add to that you get away from the science, our science, at least into social science and policy, we really have to get a hold of this business of subsidizing risk and stop doing it. And let premiums— it may be painful to do this — but at least get to the point where insurance premiums actually reflect the risk people are undertaking so that they are discouraged from moving and building in risky places.

CURWOOD: Professor Emanuel want to thank you for taking the time with us today. Kerry Emanuel is a professor emeritus of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Thanks so much.

EMANUEL: Thank you very much.

Links

Science | “Hurricane Otis Smashed into Mexico and Broke Records. Why Did No One See It Coming?”

Tropical EXperiment in MEXico (TEXMEX) Headed by Dr. Kerry Emanuel

More info on hurricane Patricia

More information on the relationship between global warming and climate change

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth