Environmental Racism in Birmingham

Air Date: Week of December 1, 2023

The Bethel Baptist Church in North Birmingham and the memorial to the parsonage that was bombed on Christmas night, 1956. (Photo: Heather Cowper, Heatheronhertravels.com, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

In North Birmingham, Alabama, racist zoning practices and industrial coke production have plagued Black communities for decades. Despite a growing focus on environmental justice from the federal government, it’s yet to be clear how new funds will help the communities in North Birmingham. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Vernon Loeb, the Executive Editor of Inside Climate News, about what he found during a reporting trip there.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The Biden Administration has made advancing environmental justice a priority and just recently announced $2 billion in Inflation Reduction Act funding for EJ and climate justice grants. These dollars are expected to help mitigate climate risks like extreme heat, install pollution monitoring systems, and clean up communities that have borne the brunt of industrial pollution. But it is yet to be clear how these funds will benefit communities like North Birmingham, Alabama, where racist practices and industrial coke production have plagued Black communities for decades. Vernon Loeb is the Executive Editor of our collaborator Inside Climate News and he reported about the environmental justice struggles in North Birmingham. Welcome to Living on Earth, Vernon!

LOEB: Thanks so much, Steve. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So first off, why don't you describe the area of North Birmingham for us and the industries that have been located there?

LOEB: Yeah. I think the most striking thing about this area in North Birmingham, which is now called the 35th Avenue Superfund site, is that it's actually three entire neighborhoods inside the Superfund site. Most Superfund sites are sort of dump sites out in the middle of nowhere. This one consists of three predominantly Black neighborhoods, really all-Black neighborhoods in North Birmingham, that are surrounded by polluting industries, primarily steel, coke and cement plants. People don't know that Birmingham was the Pittsburgh of the South up until the 50s, or 60s or even 70s, I guess. And these neighborhoods, Fairmont, Collegeville, and Harriman Park, were cheek to jowl with three major coal plants, additional steel plants, dozens of plants. And North Birmingham was a thriving part of the city that's now pretty much completely gone. And what you just have are these sort of orphaned neighborhoods surrounded by these industrial facilities, many of which are now closed.

CURWOOD: When I think of Birmingham, I think of the civil rights movement as well. What did this neighborhood have to do with that?

LOEB: It's so ironic that this Superfund site is where it is, because it includes Bethel Baptist Church, which is a national historic landmark. And it was the place where Fred Shuttlesworth was the pastor from, I think, 1955 until 1961. He was one of the leaders of the civil rights movement, and really the leader of the movement in Birmingham. And his parsonage, his home next to the church, was bombed by the Klan on Christmas night, 1956. He was at home, he was almost killed. And so this historic church and a kind of monument to the parsonage -- the parsonage was destroyed, but there's sort of a superstructural monument to it -- is now within the Superfund site. So it's a very powerful place, and to be the site now of a kind of environmental justice reckoning by the EPA, all these years after the civil rights movement in Birmingham is really incredible.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the racial practices there. How did redlining and zoning influence the pollution that locals were exposed to in this Black neighborhood?

LOEB: Yeah, well, this really is sort of the archetypal environmental justice community, because up until the 1950s, the neighborhoods themselves were zoned Black. They were zoned for Black people. It was about as racist as one could possibly imagine. And when Black people started to integrate middle class white neighborhoods, the Klan and others bombed, you know, large numbers of Black houses to keep Black people from moving into those neighborhoods. So this really is about, as I say, archetypal, racist environmental justice community, as one can imagine in this country: Black-zoned neighborhoods, surrounded by the most polluting industrial facilities you can imagine.

CURWOOD: So North Birmingham has this toxic social legacy. And now also today, a toxic health situation, a Superfund site. What kinds of substances are there that endanger the population?

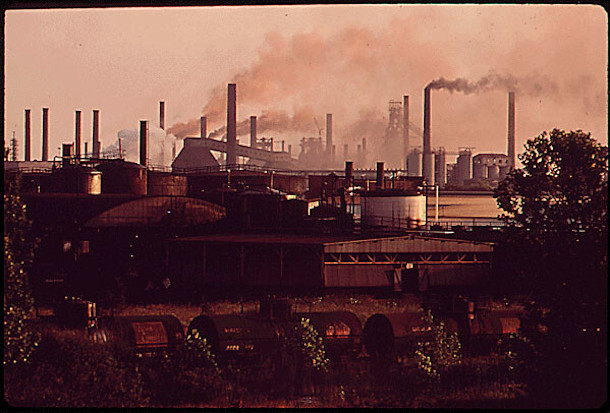

A June 1972 photograph of the U.S. Steel plant in Birmingham, Alabama. (Photo: LeRoy Woodson for EPA, Dystopos, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

LOEB: Well, it was, it became a Superfund site around 2014, when it was discovered that the soil, the topsoil that had been spread on the lawns of over 600 homes in these three neighborhoods had come from the surrounding coke plants. And it was laced with lead, and arsenic, and other very toxic elements. And now, the EPA has pretty much dug up the dirt and replaced it with clean topsoil on about 650 lawns. So the remediation of the Superfund site, per se, is pretty much done. What remains to be done is something for the neighborhoods themselves that have really fallen on ill repair because of their surroundings and because of this legacy of toxic pollution.

CURWOOD: What have been the health concerns there? I mean, stuff like coke has benzopyrene, all kinds of things that are known to lead to cancer.

LOEB: Yeah. When you go around the neighborhoods and you talk to residents, everybody will tell you about the cancer in their family. And coke is one of the most toxic substances. It's actually baked coal that's used in blast furnaces for making steel. And the emissions from a coke plant are considered human carcinogens. So these neighborhoods were surrounded by the dirtiest, most polluting facilities one can imagine. You know, as we know, it's very hard to prove causation, right? It's very hard to prove that the emissions from a coke plant half a mile from your house caused the three generations of cancer in your family. But you know, if you spend enough time in these neighborhoods and you talk to enough people, the anecdotal associations really become overwhelming. And certainly the people who live in these neighborhoods are absolutely convinced that these polluting coke plants and steel plants around the neighborhoods devastated the health of their, of their loved ones and their families.

CURWOOD: What kind of efforts have been made by public health researchers to document the health effects of these polluting plants?

Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark in Birmingham, Alabama commemorates the steel and iron industry that was once dominant in the city but resulted in harmful air, land, and water pollution there. (Photo: David Wilson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LOEB: You know, I don't think there have been extensive public health studies of the area. One thing that really caught my eye this summer when I was down there, and I was told about this by residents and by activists and by attorneys at the Southern Environmental Law Center, is the EPA decided about a year or two ago to do a cumulative impact study, looking at the cumulative impact of decades of pollution on these neighborhoods as a sort of environmental justice case study. And that really, I think, to some extent, spoke to the priority that the Biden administration has assigned to environmental justice. And I know that people in the neighborhood were, you know, really looking forward to what the results of this study were going to be. It came out a couple of months ago, and I was a little bit disappointed. It was done by the EPA Inspector General. And so it wasn't a policy office, it wasn't the Superfund program office with, you know, millions of dollars at its disposal. It was the Inspector General basically making recommendations for procedural reforms at the agency. And the conclusion was that the four major EPA programs that had been working in the area -- the water program, the air pollution program, the land pollution program, the Superfund program -- were completely siloed and never talked to each other and never really even considered the cumulative impact of, say, air pollution and ground pollution on the residents. So that is now something the EPA is trying to craft metrics to get at, you know, to resolve in the future. If you're going to be working in a neighborhood like this, you really need to look at the public health implications across all disciplines, be it air, be it water, be it land. And so that's one thing that's come out of this.

CURWOOD: So now, what's been done at this point to heal and, and rebuild this community from this toxic legacy of pollution and disinvestment?

LOEB: Well, as I say, the lawns themselves have been remediated. So most people no longer have to wake up every day and worry about their kids going out and playing in arsenic- and lead-laced dirt in their front yards. And these are small yards, these are small homes. The Southern Environmental Law Center continues to litigate against Bluestone Coke, which is one of the very nearby coke plants. The plant has been closed because of all the pollution violations that are outstanding that it has yet to deal with. And it continues to pollute a nearby stream, and that's what the ongoing litigation is about. So there are ongoing efforts to clean up Bluestone Coke. You know, there isn't a whole lot happening in these neighborhoods, sadly, and they are fading as, you know, I, I spoke to one of the neighbors, one of the leaders of a community group in one of the neighborhoods who said to me, North Birmingham is gone, there's just not a whole lot left here to try to save. And that's why this person believed that the residents there deserved to have their homes purchased at estimated fair market value, so they could, you know, move somewhere else.

CURWOOD: Yeah, let's talk about the options now for the community. You have those who say, Give us money so we can move elsewhere and reestablish. And then there are those who say, Come on, let's clean this up and make it possible for us to stay. And then I imagine there are some folks who are in the middle. So how does that play in terms of the research that you did while you were working on the story?

LOEB: Well, you know, I think there's still resources in the community to build upon, you know, beginning with Bethel Baptist, which is still a vibrant congregation, but a number of the homes are vacant and in disrepair. There have been fires, the streets need help. It feels like a part of the city that's sort of been forgotten and it's starting to become sort of abandoned.

CURWOOD: Vernon, before you go talk to us about how this environmental justice disaster in North Birmingham squares with the environmental justice initiatives in the, in the Biden administration. I mean, to what extent do you think the folks there in North Birmingham have benefited from the environmental justice promises made by the administration?

Vernon Loeb is the Executive Editor of Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Vernon Loeb)

LOEB: I don't think they've benefited at all yet. In fact, the 2021 Infrastructure Bill provided 5 billion new dollars for the Superfund program and for, quote unquote, "brownfields," that is, redevelopment of these old industrial pieces of land in cities. So there's certainly money in the Superfund program now, if somebody wanted to allocate it to these neighborhoods to again, beyond just replacing the dirt on their lawns, repaving streets, rebuilding homes and so forth. Building community centers, doing all the things that are, you know, part of the playbook for revitalizing neighborhoods. That could happen there, and it hasn't happened there yet. And I think, you know, obviously, that's what a lot of the residents in these neighborhoods are waiting for, you know, those kinds of dollars to start coming home to that Superfund site. Fascinating aspect of this site, in 2014, when the EPA started moving to include the 35th Avenue Superfund site on the so-called national priorities list, which is a listing of the most hazardous waste sites in the country, those eligible for the most funding. An executive of one of the nearby coke plants and his attorney actually bribed a state legislator to have him try to keep the 35th Avenue Superfund site off the national priorities list. And they succeeded, it's still never been added to the list. Those three people went to jail. So there was actually, you know, a bribery case that grew up around this Superfund site, as people endeavored to keep it off that national priorities list and keep it from getting additional funding. And to this day, it's never gotten any additional funding.

CURWOOD: So Vernon, what's the overall mood in Birmingham -- Black and white, about trying to deal with these horrible problems in North Birmingham?

LOEB: You know, it's certainly not the city from the 50s or 60s. It's not the city it was during the Civil Rights Movement. It has a highly respected progressive Black mayor now in Birmingham. There is, you know, considerable civic infrastructure there. There were multiple community and environmental groups at work on behalf of the residents of the Superfund site neighborhoods. And there's an office of the Southern Environmental Law Center in Birmingham, and the Southern Environmental Law Center is a real powerhouse institution, the lawyers from that law center don't mess around. I mean, they are really aggressive and they know environmental law. They are all over Bluestone Coke. And so I do think there is more than a little cause for optimism in Birmingham that the Biden administration's rhetoric about environmental justice can become a reality on some level.

CURWOOD: Vernon Loeb is the Executive Editor of our collaborator, Inside Climate News. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LOEB: It was great to be here. Thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth