A Vivid New View of Earth

Air Date: Week of July 5, 2024

This image encompasses all of the letters in the PACE acronym. Blooms of phytoplankton (P) are seen as green colors off the coast. Red dust aerosols (A) blow from western Africa over the Atlantic Ocean that is dotted with clouds (C). Minerals carried within the dust deliver key nutrients such as iron to sustain life at the base of the ocean ecosystem (E). (Photo: NASA)

A powerful new NASA satellite called PACE can look at the ocean and clouds to distinguish between different kinds of microscopic phytoplankton and aerosols from an orbit 400 miles up. PACE Project Scientist Dr. Jeremy Werdell joins Host Jenni Doering to describe how the technology works, its value to scientific research on climate change, and the real-time data it provides about water and air quality worldwide.

Transcript

DOERING: A new NASA satellite known as PACE is now collecting and beaming back vital insights on the health of our planet. The PACE mission launched in February of 2024 and is designed to gather data about Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. From an orbit 400 miles up, the sophisticated instruments on this spacecraft can even see microscopic phytoplankton and aerosols. That gives scientists a detailed view of harmful algal blooms and air pollution, in real time. Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an Oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. Dr. Werdell, welcome to Living on Earth!

WERDELL: Thank you so much. I'm really happy to be here.

DOERING: So how are you actually able to see and distinguish between different kinds of tiny particles? I mean, we're talking about like miniscule microscopic phytoplankton, aerosols that are also super tiny. And you're doing this from space.

WERDELL: It's my favorite question. And when I get to do this in like a public setting, like a bar, I love being able to walk in and be like, yeah, I can see invisible stuff in the ocean from 400 miles above the sea surface.

The NASA PACE mission launched in February 2024. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Wow.

WERDELL: It all really relates to color. The instruments we have, in many ways operate just like your eyes do. I mean, when we refer, you know, to a space based view of the ocean, you know, if you think about those beautiful pictures from International Space Station, it's the blue marble, we always call it the blue marble. But the reality is the ocean is a spectrum of color. And there are photosynthetic pigments within phytoplankton that absorb different kinds of green and blue light. So really, there are almost like 150 different shades of green. And so when we have these--

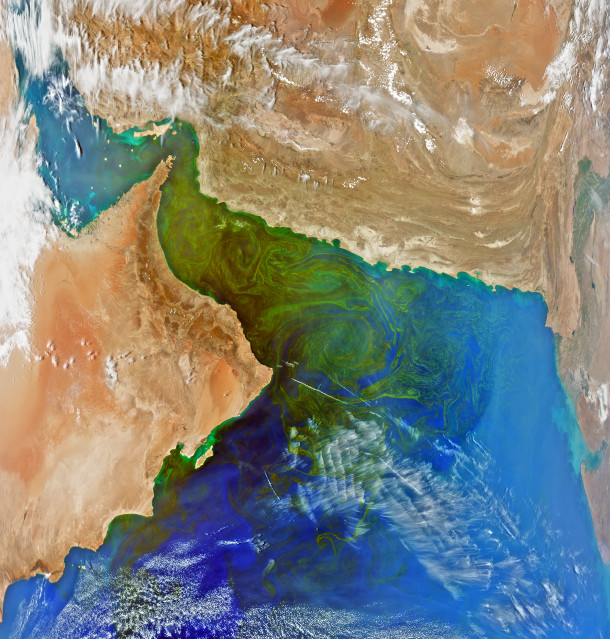

For decades, massive phytoplankton blooms have occurred during the winter in the Gulf of Oman. The swirling bands of green seen here may be caused by a phytoplankton type identified by earlier in-water studies: a dinoflagellate known as Noctiluca scintillans. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Woah, what?

WERDELL: Yeah, exactly. Think about like walking through the forest, you might not know what every different cluster of trees is. But the little subtleties in the greens and the shapes tell you, hey, this species, this plant is different than the other one. So you can start seeing subtle differences simply by looking at color. And where we have this beautiful new mission come in is this brilliant fleet of Earth, observing systems NASA and others have had for years, they only measure two greens, they only measure two blues, for example. And that is enough information to say, hey, I see a phytoplankton signature in a backdrop of everything else that might be in the ocean. But it's just saying, hey, I see phytoplankton there. With PACE, we now have all the colors of the rainbow, a continuous spectrum from the ultraviolet, the purples, all the way into the reds. And by looking at all the greens, for example, suddenly, these little differences are standing out. And from that, you can start saying, hey, I think there's a phytoplankton community there that is different than the one, you know, in this other body of water. So while there have been other missions that have done this previously, they've done it kind of on small scales, either they don't see the entire globe or they turn on and off. So with the primary instrument on PACE, it's the first time we will see the entire globe every day in this full spectrum of color.

The mechanical team assembles in the clean room where they prepared the PACE Observatory before launch. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: I mean, it almost sounds like what you're describing is like we were colorblind. And now all of a sudden, the world is full of different colors.

WERDELL: I'm gonna steal that, that's perfect.

DOERING: Oh, okay!

WERDELL: Thank you, Jenni. It's so much information that we're talking about, like thousands of unique pieces of information in a five by five kilometer box.

New Zealand's North Island and South Island each have bright blue-green "outlines" in this image. This may be caused by sediment being re-suspended from the ocean floor by the action of waves and tides. In some places, such action can stir up nutrients from the ocean depths, fueling populations of tiny algae that form the base of the marine food web, known as phytoplankton. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: And why should we care about this data? How might this information be used by the public?

WERDELL: So one of my favorite things about PACE is that it provides information that's useful on multiple timescales, and I'll focus on two. If you're thinking really near term, let's say you're not in view of the ocean, so you don't really spend a lot of time thinking about phytoplankton or biology in the ocean, that's microscopic. You still care. They form the base of the food chain. And so the food we eat comes from phytoplankton. And even if you're not a seafood connoisseur, or fan, perhaps you travel to the beach for recreation, or you know people whose livelihood is based on fishing, or owning a restaurant or hotel near the beach. Well, the ocean and that industry is very connected. So there's a ton of socioeconomic benefit in understanding the ocean. And then of course, you have the harmful species that can contaminate drinking water in bodies of water near water intake in your neighborhood, or shellfish fisheries can be closed because of toxins in the water from phytoplankton. So there are really good short term reasons to be thinking about these things, even if they're not part of your everyday mindset. Then similarly, when you pivot to the atmosphere, air quality, you know, we can inform on air quality. And not every community has the advantage of local networks that measure air quality. So now with these eyes in the sky, you have tools and assets that are free to decision makers and early warning detection systems that tell you about the quality of what you're breathing. And then if you pivot to the generational timescale, we are a climate mission. Aerosols and clouds, they interact. Aerosols are interesting because not only do they influence cloud formation, but some aerosols absorb light, some reflect, so they have different warming and cooling properties. And so if you want to understand how the atmosphere is changing, you have to understand what's in it and how it's changing the heating and cooling properties. Of course, aerosols can land on the ocean and seed phytoplankton blooms. Blooms can release certain gases and compounds that can form clouds. And then thinking on this climate scale of phytoplankton, well, they just move carbon around. Some sink faster than others. So in this conversion of carbon dioxide into organic or particulate matter, where is that all going? How are they responsible in the carbon cycle for moving carbon dioxide around, pulling it out of the atmosphere in the water? So many layers, so many layers, I could go on and on. And I know I already have, with my apologies.

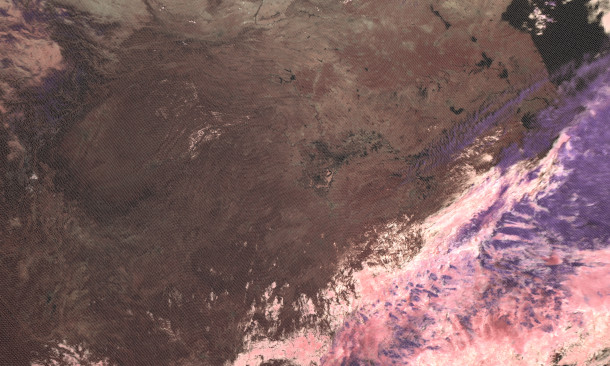

Andrew Sayer, PACE Project Science Lead for Ocean Color Instrument (OCI) Atmospheres, created this and the next image. This first one is a “true-color” version of an image of Southern China. The next image showcases OCI’s unique ability to bring out more scientific details. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Lots of layers. And it sounds like a lot of them connect back to each other.

WERDELL: They do. And that's the interoperability and interconnectedness of what we're studying.

DOERING: So how do you actually get this information out to people who could benefit from it? Like, if that's shellfish farmers who need to know about what algal blooms might be near their farms?

WERDELL: That is a great question, because it really does take a village. And in this case, we are very fortunate enough to have an Applications Program baked in to the PACE mission project. And what this group does, is essentially provide the connection to stakeholders. So listening sessions, and really, you know, kind of knocking on doors and going to meetings that, you know, we've never been to before and starting to just spread the word. And if you do that well enough, suddenly, you know, new folks become interested, which creates the second challenge, which is demystifying the use of the data, not just how do I get it? But does it come in a package that I can use easily? And that can range from fitting into a software program to, I just want it to show up on my phone, you know, is there an app? And there are examples of, of how satellite data can be used within an app environment to just give you a stoplight view of your local inland water body, you know, is it experiencing an algal bloom that you may not want to dip your toe in or have your pet swim in, to hey, it's looking clear today.

Even though the “true color” version of this image shows plain white clouds, the OCI reveals that this is a multilayered cloud system. Here, ice clouds and snow are purple, liquid clouds are pink, water is black, barren ground is brown, and vegetated areas are deep red.)

DOERING: Sounds like a weather report for algal blooms almost.

WERDELL: Which would be great. In fact, we have had some really cool interactions over a number of years with shell fisherman on the West Coast and somebody representing fishermen in Maine. And the fact that this kind of information has found its way into those communities is really satisfying for someone like myself.

The PACE spacecraft undergoes final configuration in chamber prior to door closing & Hot Soak; Solar Array engineering test unit Wing Pop and Catch Thermal Vacuum Test. (Photo: NASA)

DOERING: Jeremy, you've been working on this project from the start. What did it feel like to watch the satellite safely launch into space and get up and running?

WERDELL: Jubilation and nausea all at the same time. A mission like this takes about well, PACE took 20 years. So to get to Florida, to Kennedy Space Center and actually see the Falcon nine rocket and the launch pad was profound. And then, of course, we had two weather delays for the launch.

Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an Oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. (Photo: Courtesy of Jeremy Werdell)

And it's the middle of the night. So it's hard enough staying up and keeping the energy, you know, going, and then you watch the launch. And then you have to wait for roughly a half an hour to make sure that the solar arrays properly deploy and become power positive. And then you can finally breathe. With everything in between, I mean, you're just, you're just numb. But on the far side of that, wow. Just wow.

DOERING: Dr. Jeremy Werdell is an oceanographer in the Ocean Ecology Lab at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and the Project Scientist for the PACE mission. Thank you so much, Jeremy.

WERDELL: Thank you so much. Love doing this. It's really appreciated.

Links

Read more about the PACE Program

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth