Civil Rights and Environmental Justice

Air Date: Week of February 21, 2025

Rev. Ben Chavis celebrates the pardon of the Wilmington 10. Rev. Chavis first came to national prominence as a member of the Wilmington 10, a group of civil rights activists who were unjustly convicted of committing arson. Chavis was sentenced to serve 34 years in state prison. The group’s convictions were overturned on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct, and they were freed in 1980. (Photo: United Church of Christ, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

For Black History Month, civil rights and EJ leader Rev. Benjamin Chavis joins Host Steve Curwood to connect the dots between the civil rights and environmental justice movements. He reflects on the first EJ battle, how he coined the term “environmental racism,” and the path forward for the EJ movement during a Trump administration that refuses to acknowledge environmental injustice.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Today for Black History month we are meeting a living legend. Back in 1981, civil rights leader the Rev Ben Chavis coined the phrase environmental racism after he was arrested for protesting North Carolina’s decision to dump tons of toxic waste in poor, Black Warren County. Six weeks of demonstrations failed to stop the toxic dump, but the publicity sparked a movement that’s now known as environmental justice. North Carolina’s governor Jim Hunt eventually apologized, but it took until 2004 before the PCBs in Warren County were finally cleaned up. And environmental racism in America is still a problem. Older black people die three times as often as whites from pollution related diseases, Puerto Ricans have nearly double the asthma incidence and 75 percent of the water for Hopi Native Americans contains arsenic. The Biden administration made environmental justice a key part of EPA policy, but the Trump Administration is cutting EJ budgets and its very mention. EJ pioneer Ben Chavis joins us now from Baltimore, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHAVIS: Well, thank you very much. I am pleased to be on the program with you. I tell people all the time, the best way to celebrate black history is to make some more history. And certainly, after looking at the Super Bowl, we know that Black history is American history. You know, there are a lot of people thought that Black history is not a part of America, or America or America is not a part of Black history, but from the earliest days of the Revolutionary War, African Americans have participated in trying to gain and strive toward a more perfect union in what's now known as a democracy as fragile as it is.

CURWOOD: So let's spin the clock back to 1981. So in 1981 you found yourself in rural Warren County, North Carolina, not doing a voting rights protest, but something else. What were you doing?

CHAVIS: We were protesting the unjust, unfair and what we believe was illegal dumping of tons of PCB contaminated soil. PCB is polychlorinated biphenyls, very cancer causing carcinogenic substance. Warren County was the poorest county of the 100 counties in North Carolina, but also Warren County was the most predominately black county in North Carolina, agricultural, rural, and the water aquifer level is very shallow. What I mean is most of people got the water in one kind from well water. Did not have public source of water. So that's the last place where you want to dig a hole and dump 10s of carcinogenic, cancer causing material. This is 1981-1982 and, of course, there was debate. Reagan is president, and you had a head of the EPA at that time who didn't believe in environmental justice, who didn't believe in environmental racism. And quite frankly, my background was civil rights. So this is the first time that the Civil Rights Movement intersected in a formal way with the environmental movement.

CURWOOD: By the way, PCBs, which are dangerous chemicals, are just one set of chemical bonds away from dioxin, which we know is really bad for us. Yes, so what happened when you started marching to protest the dumping of this really toxic stuff in this black community.

CHAVIS: Well, ironically, firsthand, I got calls from some of my civil rights colleagues saying, Ben, this is an environmental matter. It's not civil rights. I said, Oh no, it is civil rights. And of course, some of the people in the environmental movement said, Well, this is a black protest. Has nothing to do with environment. So because 500 people, including myself, were arrested in Warren County in 1981-1982 it brought national attention to this landfill in Warren County. And as a result of the national attention, we begin to hear from the southwest part of the United States, from Mississippi, Alabama, Flint, Michigan, all over the country. People say, you know, we have environmental problems here, Cancer Alley in Louisiana, very famous place, but nobody was paying attention. Everybody saw all these spots as isolated incidents. After Warren County, people began to connect the dots, and that's why we say Warren County is sort of the birthplace of the environmental justice movement.

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say you coined the term environmental racism?

CHAVIS: Well, it's very fair, because it's true. One night in the Warren County Jail, it just came upon me. You know, this is, it's racism, but it's, it's environmental racism. And I got a little sheet of paper and jotted out a definition: environmental racism is racial discrimination and environmental policy making and environmental enforcement and environmental remediation, but it's also the exclusion of people of color in the decision-making around environmental justice, environmental hazards and environmental policy making and close now, today, in 2025, there's a connection between environmental justice and climate justice. Some are similar aspects of both connect.

CURWOOD: Tell me, looking back over these last 40 plus years, what were some of the lessons you felt that you learned from the Warren County struggle?

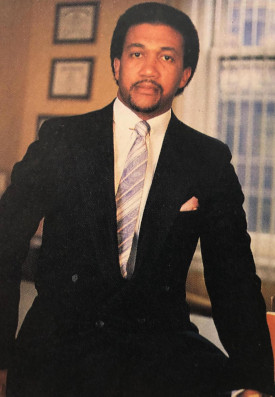

A former head of the NAACP, the Rev. Ben Chavis is president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association. He helped convene the first People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991 to help highlight environmental issues facing African Americans and other people of color. (Photo: Courtesy of Ben Chavis)

CHAVIS: So, number one, we learned the importance of grassroots organizing. Number two, we learned that we have to be more definitive in how we define what is the movement of environmental justice. And I'm so pleased that at that the first People of Color Environmental Summit in 1991 in Washington, DC, we established the 17 principles of environmental justice. I teach a course now at Duke University on environmental justice using those 17 principles, which still applies the vision that we had back then, being a multiracial, multilingual,multicultural movement around this issue and those principles. And we really thank the leaders in the Native American community during that time to help us to see the sacredness of the Earth. You know, I'm a preacher, so I gotta quote this Bible verse, The Earth is the Lord's and the fullness thereof. That's from the Psalms. So if the earth belongs to the Lord, that means that the Earth does not belong to the government. The Earth does not belong to a petrochemical company. The Earth does not belong to people who want to do things to harm the Earth or to harm the environment, or to harm the planet or to harm the atmosphere. And then the third thing we learn is that each movement has to regenerate itself. Young people, I'm very encouraged by millennials and Generation Z that have a stronger consciousness of the importance of climate and environment over against what it was 40 years ago.

CURWOOD: Where are some communities where you have seen the most flagrant cases of environmental racism?

CHAVIS: While in America, the most flagrant is cancer alley in Louisiana, cancer alley has gone on for decades. That's between Baton Rouge and New Orleans because of the proximity to those companies that emit poisons into the atmosphere, into the water and to the land, and obviously it gets into the people and core. More recently, Flint, Michigan. So the people in Flint, Michigan who have been lead poisoned because of bad lead pipes and poor environmental policy and even the denial of the state of Michigan one point that they had a problem those poor people, and they say, Oh, well, we have fresh water now, yes, but they're going to have to live for the rest of their life with the contamination of their body to lead portion. That's why, in a number of cases, the struggle for environmental justice is a matter of life and death. The struggle for climate justice is a matter of life and death, and there'll be consequences.

CURWOOD: So we're talking about something that began in history back in 1981- 82, but tell me what's going on today? What percentage of African Americans are more likely to live in areas situated near hazardous waste facilities these days?

CHAVIS: Thank you. It's a very good question, and I would like to go to first 1987 where the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial justice. I was the director at that time. We commissioned the first national study to ask that question. It's interesting, when you do research, it's not so much counting numbers; it's what questions do you ask of the numbers. No one had ever asked Blacks or Latinos or Native Americans or Asian Americans or even poor whites disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards. And what we found was that it wasn't poverty, it was race that was the number one factor that determined where all these sites were around the United States, and that's what led to the first People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991. But to answer your question, today, I'm very pleased to tell you that what started as a small rural environmental justice movement in Warren County is now a global movement. It's not only a movement throughout the United States, but the United Nations now cites environmental justice. I know they're dismantling the EPA now, but until recently, the EPA had an official Office of Environmental Justice in the Environmental Protection Agency. So we've done a lot. We've made a progress. We still haven't gotten to where we should be, but we've made a lot of progress over the number of years as a result of Warren County. So today, African Americans are still disproportionately exposed. From our current research, we believe that 20% of all African American families and communities are exposed to environmental hazards.

The Rev. Dr. Benjamin Chavis is an environmental justice and civil rights activist who is credited with first using the term “environmental racism” during protests in Warren County, N.C., in 1981-82. That was the first time environmental justice issues for people of color were viewed as an issue of civil rights. (Photo: Courtesy of Ben Chavis)

CURWOOD: And how does that compare to white America.

CHAVIS: White America is less than 2%. So racial discrimination, keep in mind, housing discrimination, racial discrimination, voter discrimination, all these things are connected, and that's why you can't just be focused on one aspect, because the others will come back to bite you. And that's why we have to have a more holistic view of what the movement is about, what the freedom movement is about, what the equal movement is about, and this whole debate now about diversity, equity, inclusion, I think, is a diversion, because the truth of the matter is, there's only one race, and that's the human race. We're all part of one human family, but we we've been so divided, been so pitted upon one another. And this whole thing of white supremacy is also like a cancer that is in desperate need of healing.

CURWOOD: Within the last month or so, we've seen the incoming President of the United States shut down the environmental justice programs at the Environmental Protection Agency. To what extent is that racism, in your view?

CHAVIS: Well, I think it is an example of environmental racism. I think it's an example of climate injustice as well as environmental injustice. And what's going to happen is some of the very people that voted for Trump are also going to suffer as a result of these policies. When you dismantle the CDC, when you dismantle the EPA, when you dismantle even the Department of Education, who is that going to hurt? It's going to hurt the majority of not only American children, young people, but it's also going to put our families and communities in greater jeopardy. I come from a movement perspective. I think these harsh and unjust policies that we're witnessing today is going to cause a groundswell, not just to react, but also to demand that we have to learn from our history. This is Black History Month. What do you mean by that? When you learn from the history, not to repeat the history, you have to learn from it.

CURWOOD: So you're a minister, Yes, Ben Chavis. It was people of faith who really led the Civil Rights Movement. But when I go to a gathering of environmental activists, mostly white ones, yes, I don't hear a whole lot of prayers. Right. To what extent is there a spirituality gap in the environmental movement in this country? Do you think?

CHAVIS: Well, yes, the answer is yes, there is a spirituality gap. Because keep in mind, prior to 1991 the environmental justice movement was not integrated, it was not desegregated. So while we have one of my colleagues Ben Jealous, now over the Sierra Club, I'm just using that as an example. Faith is important. In my view. You have to believe in what you're doing, not just have an intellectual exercise or debate. I think there's a cause of faith that people want to be aligned to what is righteous against what is perceived to be unrighteous, and that's where faith comes in. I call upon the Black church today to renew its front line position in civil rights; to renew its front line position in environmental rights or climate rights. I think some of our churches, I'll speak for the Black churches, have become so prosperity oriented, the sense of commitment to social justice or the social gospel is not as strong as it once was, but I think that can be renewed and revitalized.

CURWOOD: So, it's a personal question, but how tired are you now of fighting this same fight over and over again?

CHAVIS: Good question. Well, you know, I'm 77 years old. I've been involved in civil rights movement since I was 12. And I can say without any fear of contradiction, that I look back over the years and look where we are now, I see enormous progress. I think a lot of times, if we only see our deficits, if we only see our disappointments, if you only see our failures, you won't see our triumphs, our successes, our overcoming. We used to sing we should overcome in the 1960s. We were not overcoming, but we sang that song because we knew one day we will overcome. And so the way I look at I ain't tired. In fact, when I teach this course at Duke, I get rejuvenated seeing young people who have open minds, who are hungry and thirsty for truth. And so that gives me a sense of not only hope, but it gives me a sense of perspective that our world is changing despite all what is going on. There are more people today conscious of the oneness of our humanity than it was 50 or 60 years ago, and for that, that makes me optimistic.

CURWOOD: What's your advice to America at this juncture about the climate and environmental justice emergency, as some would say?

Ben Chavis with then-candidate Joe Biden in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2020. During the Biden Administration, environmental justice was put at the center of EPA policy. President Biden, through the Inflation Reduction Act, earmarked billions to address EJ issues. (Photo: Courtesy of Ben Chavis)

CHAVIS: My famous quote from Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, my favorite quote.

CURWOOD: This is somebody you worked with, by the way. I mean, people should know that you were, you were a kid when you were involved.

CHAVIS: As a teenager, I was the youth coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference my home state of North Carolina. I was 14-15, years old. Put my age up. I was driving before I should have been driving. Had mobility. And I learned a lot from Dr King, from Abernathy, from Andrew Young, from a long list of mentors that I was blessed to have. But Dr King said, “an injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” So I would say an environmental justice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. I would say a climate Injustice anywhere is affected climate justice everywhere. So I think that what I've learned in the movement is change is possible to the extent to which people get involved and stay involved and not let their spirit get broken. You asked me earlier about the importance of faith. One of the things I tell young people, and I tell people my age, whatever happens to you in life, there will be disappointments, there will be trials and tribulations, but at the end of the day, never let anyone or anything break your spirit. Having that strong spirit to stand up, to speak out, to organize, to mobilize, is something that is really needed today. A lot of people had their hearts broken because Kamala Harris did not win the election. Well, we got to mend our broken hearts. We have to mend our broken spirits. We just can't go down in the dumps and fall down on someone who wants to be king of America. What we have to do is to mobilize and organize anew. And I believe that the God of our ancestors will be the God of our future, and answer our prayers. But in order to have the prayers answered, you got to pray, you know, you got to have faith. And so that's what keeps me going every day. I work every day, even though I'm 77 and I'm glad to still have the strength and the good health to work and continue to make a contribution.

CURWOOD: Reverend Ben Chavis is still fighting the fight of environmental racism that he helped begin back in Warren County, North Carolina in 1981 thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CHAVIS: Thank you for the opportunity.

Links

Grist | “The Event that Changed the Environmental Movement Forever”

More on The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth