December 13, 2002

Air Date: December 13, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Cheney’s Energy Task Force

View the page for this story

The White House scored a victory when a judge tossed out the suit brought by Congress' General Accounting Office demanding documents related to Vice President Cheney's Energy Task Force. But there are still several cases pending that demand the same information. Host Steve Curwood talks with Russell Verney of Judicial Watch about his group's pending lawsuit. (05:30)

Environmental Oversight

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

The U.S. government is a major funding source of development projects in countries around the globe. But critics contend it isn’t doing enough to ensure those projects aren’t harming the environment. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum reports from Washington. (06:00)

Health Note/Averting River Blindness

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

This month, the World Health Organization marks the 30th anniversary of its campaign against river blindness, once the scourge of West Africa. Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports. (01:15)

Almanac/Moonwalk

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the last men on the moon. Thirty years ago, Apollo 17 left the lunar surface and, so far, no one's gone back. (01:30)

A Living Learning Space

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood visits with Oberlin College professor David Orr in the new environmental studies building. As Professor Orr explains, the building was created with careful consideration of its environmental impact, and it serves as an educational tool, too. (08:00)

In Search of Home

/ Tom Montgomery-FateView the page for this story

Longing to go back to his birthplace in Iowa, Chicago commentator Tom Montgomery-Fate ponders the meaning of home. (03:00)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

Developments in stories we’ve been following. (03:00)

Animal Note/Wake-up Call

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on new research on the chemical ways fruit flies can influence one another's circadian clocks. (01:20)

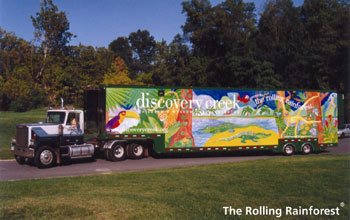

Rolling Rainforest

View the page for this story

Students in Washington, DC are getting a chance to visit the rainforest – it’s right in their school parking lot. Living on Earth followed students at the Brent Elementary School as they forayed into the jungle. (03:30)

The Cofans of the Amazon

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

From Ecuador, the story of an Amazonian tribe that fought the usual battle with oil companies and the government to keep its land. But as Sandy Hausman reports, this story has a twist. With the help of an American man raised as one of them, the Cofan Indians actually won their battle. (13:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Sandy HausmanGUESTS: Russell Verney, David OrrCOMMENTATORS: Tom Montgomery-Fate UPDATES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood. A federal judge has given the White House the latest round in its bid to keep the proceedings of the energy task force secret from Congress. But this ruling won’t stop lawsuits by conservative watchdog groups and liberal environmentalists who are seeking the same documents.

VERNEY: If Hillary Clinton has to reveal her healthcare records, which we believe she certainly should have in the healthcare task force, so shouldn’t the energy task force under President Bush.

CURWOOD: Also, the tale of an American family who lived among Indians in the Amazon.

B. BORMAN: I still remember the time that we forgot some money when we left the village. It was laying out on the table outside. Came back a month later and it was laying there. I mean, nobody would have even thought of stealing it.

CURWOOD: Now they’re trying to protect the tribe from being wiped out by development. Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

Cheney’s Energy Task Force

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The secrecy surrounding Vice President Cheney’s energy task force remains in place, at least for now. A federal judge in Washington D.C. has dismissed a suit brought by the General Accounting Office of Congress seeking records of the task force.

But other lawsuits seeking the same information remain active. In one case, a federal judge has ordered the White House to turn over the documents. That order has been stayed pending an appeal by the administration.

I’m joined now by Russell Verney. He’s the national advisor of Judicial Watch, a public interest group that investigates and prosecutes government corruption. Judicial Watch, along with the Sierra Club, brought the case that the administration is appealing.

Before we get to the particulars of your case, Mr. Verney, why do you think the judge dismissed the GAO suit?

VERNEY: When a case comes before the court, and especially one involving constitutional issues, some very difficult issues such as this one: separation of power between the legislative and the executive branch, the court doesn’t have to reach that part of the decision, that tough part, if there’s an easier part that rules the case out.

And in the situation of the Government Accounting Office bringing a claim against the White House, the court was able to say that the Government Accounting Office, an extension of Congress but not Congress itself and not authorized by any resolution or vote of Congress or a committee of Congress, this extension of Congress did not have the standing, the right to come to court with this complaint.

So if they want the court to reach the constitutional issues of separation of power and does the Congress have oversight over this committee, the energy task force that the Vice President set up, the General Accounting Office is going to have to go back to Congress and get authority from Congress to bring this matter to court.

CURWOOD: What does this decision against the GAO mean for groups such as yours, Judicial Watch, and like-minded citizens who want to be able to see just how the government goes about its business?

VERNEY: Well, I don’t think this decision has an impact on groups like Judicial Watch, a nonprofit public interest law firm that looks for abuse in power or corruption in government and investigates and prosecutes.

So, we asked for these records back in April of 2001 under the Freedom of Information Act and we have three orders from the court directing the Vice President to release the information that the GAO was requesting and considerably more. We have contempt motions pending before the court because of the failure to release the documents by the executive branch, and we’re expecting to get some of those documents from the White House.

We’ve already received some 36,000 pages or more from other agencies of the government that were involved in these task force meetings but we want the White House records, too, and we believe we’re going to get those. And if Hillary Clinton has to reveal her healthcare records, which we believe she certainly should have in the healthcare task force, so shouldn’t the energy task force under President Bush.

CURWOOD: By the way, you say you’ve gotten some 36,000 documents. Anything interesting in those documents so far from your lawsuit?

VERNEY: Well, there were quite a few things that were interesting. Many of your listeners may remember that last January, very begrudgingly, the White House admitted having met with officials of Enron and they had a list of, sort of, a shopping list of what Enron would like to see in law. And by and large, they all wound up in law.

So yes, there were a lot of interesting things that have come out of the disclosures so far. We think there is more to come, otherwise they wouldn’t be fighting tooth and nail not to disclose it.

CURWOOD: Judicial Watch is perceived by some as a conservative watchdog group. The Sierra Club is perceived by some as a liberal environmental group. You have joined together, I gather, on this lawsuit, and on the surface of it are rather strange bedfellows. What’s it like to work together on this issue?

VERNEY: The working relationship between Judicial Watch and Sierra Club is very good on this issue because we have common interests that we’re pursuing, which is the public release of information held by the government. Judicial Watch was the first to start this process. Sierra Club, who had also filed a Freedom of Information request, was about a month behind us in the process, but when they got to court the courts then put the two cases together and said, this is all the same issue.

CURWOOD: Thinking back in history, what other White Houses have treated courts this way?

VERNEY: Well, I suppose there have been plenty of conflicts in every White House with respect to the courts. There certainly was a lot of that during the Clinton administration. I don’t know if it ever got to this stage of conflict, but you’ve had legal questions arising over the sharing of information, whether it’s with the independent counsel laws, special counsel laws, Congressional investigations that have led to these arguments over the years, but this has become quite drug out.

And you would think that it’s over a very small matter, the releasing of documents that created a public policy proposal. I mean, we’re not talking Iran-Contra here. We’re talking about a simple creation of an energy policy for America. Who was involved? And the more they seem to want to fight the court system, the judiciary, the equal branch of government, the more you have to wonder what is it they don't want the public to know.

CURWOOD: Russell Verney is the national advisor for Judicial Watch, a public interest group that investigates and prosecutes government corruption. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

VERNEY: It’s been a pleasure and an honor to visit with all of your listeners.

Environmental Oversight

CURWOOD: The Untied States plays an influential role in determining the lending practices of international institutions such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. Federal law requires US agencies to review international development projects for significant environmental impacts. But critics say that system has broken down. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum reports from Washington.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Until last September, John McKnight Fitzgerald was the environmental policy analyst at the US Agency for International Development, or AID.

FITZGERALD: My job was to review World Bank projects and projects of other multi-lateral development banks, as they’re called, to see what they were likely to do to the environment and to indigenous peoples.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: And Fitzgerald was to report to Congress those projects, like dams, pipelines or logging that posed the most risk. But in September, he was removed from his job and now AID plans to eliminate the analyst position altogether. Fitzgerald claims he was punished for challenging the Treasury Department when it attempted to soften his critiques of development projects in his 2001 report to Congress.

FITZGERALD: There were a number of different instances where we wrote originally that failure to have an environmental impact statement for this particular loan was, we felt, a violation of the law, and Treasury would not have us say that. So AID accepted a toning down of the language to say that it was inconvenient or made it difficult for us to review the impact without having a real environmental impact assessment. Well, that was only half the point.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Also in his original draft Fitzgerald wrote a 40-page summary of what he believed were systemic problems preventing the banks and the U.S. government from adequately protecting the environment of developing countries. It was this critique, he says, which most angered Treasury officials and led to its wholesale removal in the final draft to Congress.

Randy Quarles is Treasury’s under-secretary for international affairs. He wasn’t involved in editing Fitzgerald’s draft, but he says the purpose of the annual report is clear.

QUARLES: The principal role of that report should be to describe over the reporting period what decisions have come before the international financial institutions and how those international financial institutions have responded and what actions the U.S. government has taken…and that’s what those reports do.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Instead, a memo from Treasury to AID said Fitzgerald’s report lacks this focus and thus bears little resemblance to previous AID reports. Treasury’s Quarles says there are other forums which do explore broader policy questions like the ones Fitzgerald posed. As for critics who charge that Treasury views the environment largely as an obstacle to development, Quarles says that’s simply not the case.

QUARLES: With respect to the environmental policy of the multilateral development banks, the U.S. government and the executive directors who report to the Treasury have been voices in these institutions, frequently the only voice in these institutions, for improving their environmental policies.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Quarles describes the relationship between AID and Treasury as a collegial one. And AID says the reason Fitzgerald lost his job is not politics but bureaucracy. AID is undergoing a major reorganization which will move environmental staff from one bureau to another. Instead of assigning one worker to the bank reviews, the task will be spread out among a few employees.

PELOSI: I have serious questions about the elimination of the position of the environmental analyst.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat from California who will serve as her party’s leader in the House next year, says she’s concerned that the loss of a full-time analyst may be part of a broader effort by the Bush administration to undermine U.S. oversight of development projects. It was Pelosi who wrote the law in 1989 that first required this oversight and led to the creation of the analyst position at AID.

PELOSI: At the time, there was a great deal of degradation of the environment that was participated in by the World Bank and other multilateral development banks. These loans were made with the cooperation and support of the United States. So the purpose of the legislation, which later became an amendment to a larger bill, was to make sure that no loans were made for environmental projects unless there was an environmental assessment made and unless that assessment was made public to the people in the region and internationally.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Pelosi says the banks have made a lot of progress since that time in taking the environment more seriously. But she warns there are still problems. Environmental assessments, for example, often aren’t undertaken until after a decision is made about funding of project.

Others in Congress and environmental groups say Treasury has repeatedly supported loans for controversial projects despite negative environmental reviews by AID. They say AID’s relationship to Treasury shouldn’t necessarily be a collegial one but one of independent oversight. Some Congressional staff are now drafting language to strengthen Pelosi’s original legislation.

Meanwhile, John McKnight Fitzgerald has filed a whistleblower complaint, alleging he was removed to silence his criticism. And one U.S.-funded bank is considering a loan to a controversial pipeline project already underway in Peru’s rainforest.

For Living on Earth, I’m Anna Solomon-Greenbaum in Washington.

Health Note/Averting River Blindness

CURWOOD: Just ahead, if walls could talk, they’d be giving a lecture at Oberlin’s new environmental studies building. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: This month, the World Health Organization marks the end of its nearly 30-year campaign against river blindness, a disease that once ravaged the people of West Africa. River blindness is caused by a parasitic worm that can survive up to 14 years in the human body. The worms are transmitted through the bite of black flies that live near water. The parasite can cause lesions of the eye that can lead to blindness.

When the campaign began, more than one million people in West Africa suffered from the disease. In high impact areas, one-third of the population had severe vision impairment and up to 10 percent were completely blind. In addition, many farm fields in the region were abandoned out of fear of contracting river blindness.

The effort to end the scourge began with the elimination of black fly larvae. More than half a million square miles were sprayed with insecticide. In addition, a pharmaceutical company donated a new drug that proved to be effective against the disease. Today, the parasite has been practically wiped out in West Africa. Aside from putting an end to the physical misery, the success of the program has meant that more than 60 million acres of fertile land can now be recultivated.

That’s this week’s health update. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Samite of Uganda, “Munomuno” THE BEST OF WORLD MUSIC (Rhino, 1993)]

Almanac/Moonwalk

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: The Police, “Walking on the Moon” ZENYATTA MONDATTA (A&M, 1990)]

CURWOOD: Thirty years ago this week, Eugene Cernan and Jack Schmitt left the last human footprints on the surface of the moon. The astronauts of Apollo 17 had just completed the sixth moon landing.

The only scientist among the 12 people who have walked on the moon is Jack Schmitt. He is a geologist and, as it turns out, was the right man for the job when he literally stumbled across some strange orange soil. He scooped up samples of the lunar dirt to bring back to earth. At first, NASA thought it might be iron oxidized by water, and water meant there could be life on the moon. But geologists later determined the grit was cooled lava from a volcanic explosion on the moon about three and a half billion years before Schmitt and Cernan paid their visit.

During Apollo 17’s three-day stay the crew set a number of space records. They traveled 21 miles on the lunar surface and collected 242 pounds of moon rocks. But despite the overall success of the Apollo missions, media coverage and public interest in lunar landings was waning. America had already won the space race and at the time ending the war in Vietnam seemed a more pressing national concern. So when they blasted off, Schmitt and Cernan had no idea they might be the last men on the moon

CERNAN (TRANSMISSION FROM MOON): We leave as we came, and God-willing as we shall return, with faith and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.

CURWOOD: NASA still has no immediate plans to return people to the moon but the space agency is considering it as a training ground for future missions to the planet Mars.

And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

Related links:

- Apollo 17 Audio Library audio clips

- Apollo 17 Video Library

A Living Learning Space

[SOUND OF SQUEAKING HINGES]

CURWOOD: Tell me about these doors. It sure was tough getting in here. I really had to push.

ORR: Well, they are heavy. These are– this is an airlock entry, and so you open the outer door first and you walk through a space, and then you have to open a second door. We built an entryway that’s efficient to keep heat and cool or coolness in the building, depending on the season.

[FOOTSTEPS IN CORRIDOR]

CURWOOD: David Orr is showing off his brainchild. He’s leading me through the entrance of the new Adam Joseph Lewis Environmental Studies Building at Oberlin College in Ohio. This is one of the greenest buildings in the nation and it’s easy to see why. Above our heads an array of solar panels covers the vaulted roof. Trees in the atrium catch some of the sunlight that pours in. Across the way, there’s a wall of glass so you can look out into a small constructed wetland. And interior windows allow visitors to see inside the classrooms that line most of the building.

Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies

ORR: So we tried to make a space in the building that functions a lot like a town square.

CURWOOD: David Orr heads the Environmental Studies Department at Oberlin College. When it came time to construct a new home for his department, he wanted a building that would generate its own energy, clean its own water, and serve as a tool of instruction. Every system in the building is designed to be efficient and sustainable.

[TOILET FLUSHING]

ORR: Steve, that water from the toilet goes out to an anaerobic digester and then comes back in through what looks like a tropical greenhouse, but has actually got a name called “a living machine.” The process is wastewater, so the wastewater here goes through a biological process. It looks like a greenhouse, it functions like a wetland. Then that water goes out to a storage tank behind us in the berm comes back in the building to flush toilets.

[FOOTSTEPS IN CORRIDOR]

CURWOOD: What are we looking at here?

ORR: Behind these two doors are four tanks that are seven-feet deep, three-and-a-half feet below the level of the gravel bed. When you flush a toilet in this building, the wastewater goes out to an anaerobic digester on the east side and it comes back into the tank directly in front of us. It has plants that are six or seven feet high, and then it flows through each of these four tanks, it comes back into the gravel bed, moving toward us now into a sump and then back out to another tank, so it comes back into the building after flushing toilets. Basically it’s using plants to take out phosphorous and nitrogen from wastewater, so it’s converted human waste into plant tissues.

CURWOOD: What’s it smell like in here?

ORR: Well, I’ll show you, let’s go in.

[KEYS OPENING DOOR]

ORR: You tell me.

[SOUND OF ELECTRIC MOTOR AND DRIPPING WATER]

CURWOOD: Hey, this isn’t bad. It’s not roses, but it’s not bad. It’s, in fact, quite pleasant.

ORR: Smells like a greenhouse, and that’s really what it is. What’s occurring here is what would occur in any wetland, it’s natural processes but now in a form of a human-made device with tanks and pumps and pipes, but lots of plants. And it looks like a tropical greenhouse.

[FOOTSTEPS IN CORRIDOR]

CURWOOD: Can you describe for me where we are?

ORR: What you’re looking at is a computer monitor that shows the amount of energy generated or used in the building. This will eventually be interactive, but this data collected in the building on energy systems goes out to the National Renewable Energy Lab in Colorado and then it comes back here. But we’re showing how the building actually works. If you watch that screen long enough, it will change and eventfully there will be a water analysis come up. But this space is designed for people in the building to see how this space is actually working.

CURWOOD: Now, let’s see the center gauge there. It says when the blue line is below zero, the center is exporting renewable solar energy to the Ohio power grid. You must like that.

ORR: We do. Ohio is what’s called “a net leader” in states, so you can buy and sell at roughly the same rate. So we’re a power plant but at nighttime we draw from the grid. On a sunny day, yesterday we were sending power back out on the grid. And on average last year we generated about 57 percent of the energy for this building from sunlight.

CURWOOD: So, let’s see, I look down and this is a [STOMPS FOOT ON FLOOR] nice tile floor but it’s not just for looking good, I guess.

ORR: This is actually a heat sink. Right behind you is a glass curtained wall that is two stories high and that emits – it’s facing south, and that emits sunlight. Sunlight strikes the floor in the wintertime as the summer – pardon me, as the winter sun drops in the sky, that shadow line moves back deeper into the building. So this is a passive way to heat the structure. Below the floor, which is concrete covered with slate, is an insulation layer, so you don’t lose a lot of heat down into the ground. But this is a way to heat buildings without cost.

CURWOOD: How did you get the idea for this building?

ORR: The idea behind the building, the making of the building and the operations of the building are that we would make a space that would become educational, not just a place where you have classes. So this building begins to function as a laboratory for solar technologies, for data gathering and analysis, for water purification, for landscape management.

CURWOOD: How does this building project fit in with your concerns? You’ve written about teaching people to rethink the political basis of our society.

ORR: Thoreau says that Walden, he went to Walden to drive some of the problems of living into a place where he could study them. We’ve done some of the same here with this building. It’s designed to bring some of the problems with sustainability that students will have to wrestle with in the 21st century here into this particular place.

CURWOOD: Why aren’t there more buildings like this at colleges? In fact, where building, new buildings are proposed and people even quote your work, there seems to be a fair amount of resistance to doing buildings like this.

ORR: I think the resistance is falling away pretty rapidly. I think there is a movement now to build buildings like this. We can identify about 70 or 80 buildings on college campuses that have been influenced by this project or are trying to copy what we’ve done here, in part or entirely.

Most of the resistance is going to be around issues of cost, and you can build high-performance buildings, you can make them educational, within the cost structure of conventional building costs, or you can come in lower.

Now this building provides, eventually it will provide upwards of 80 or 90 percent perhaps of its own electric needs. It’s an all-electric building. So we don’t have a large electric bill or power bill for this building. So there are economic reasons to begin to move in this direction as well.

CURWOOD: How important do you think it is for all buildings to be instructive vis-à-vis having academic or school buildings be instructive?

ORR: All buildings are instructive, whether we call them instructive or not. One of the problems is we compete with the power of shopping malls, freeways, urban sprawl and all of that is instructive in ways we don’t necessarily want to admit. But it tells the young people that energy is cheap, sprawl is okay, you can pave over land. That’s very instructive. And so the issue here is how to begin to make the built environment smarter and instructive in the right kinds of ways, to begin to connect us to each other, to landscapes, to future generations, to people elsewhere.

CURWOOD: I want to thank you for taking this time. David Orr is Professor of Environmental Studies and Chairman of the Environmental Studies Department at Oberlin College.

ORR: Thank you, Steve. Nice to be here.

Related links:

- Info on David Orr

- Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies

In Search of Home

CURWOOD: In our increasingly mobile society, the idea of home is becoming less and less clear. On a recent trip to his native Iowa, commentator Tom Montgomery-Fate wondered if home is a real place or just a state of mind.

MONTGOMERY-FATE: I’ve lived in Chicago for 15 years but I don't feel at home, not in the city or the western suburbs where I now live. Coming from a small town in Iowa, I don’t handle the human density or frenetic energy of the city very well. It tires rather than inspires me. But so do the suburbs. The tangle of eight-lane arteries clogged 24/7 with millions of cars on their way to 200-acre malls and 400-acre parking lots or perhaps to a 30-plex movie theater.

Go west, young man. My wife Carol and I keep moving. We started on the city’s south side and every five or six years we drift another 10 or 15 miles west. I’m on a slow, meandering journey home to Iowa, place I’ll always come from.

The Latin roots of the word “nostalgia” mean homesick. I wonder about this today as we drive west on Interstate 88 back to Iowa. It’s dusk and we’re in the middle of Illinois, cruising through fields of corn stubble and past strings of cows plodding back toward the barn. In the distance a cloud of synchronized black flecks, sparrows, abruptly and beautifully change direction, like a fistful of pepper caught in a swirl of wind. Day slips into night and the horizon, the only hard line left in the world, finally disappears.

Wendell Berry once wrote that trees are immobile yet flexible. People of course needn’t be either. Few bloom where they are planted, or are planted at all. Roots have become a liability. We increasingly associate success with being mobile and accessible. We can work and live anywhere with a laptop and a cell phone. Starbucks have become the makeshift offices for an army of small entrepreneurs.

Several years ago while driving through Lancaster County, Pennsylvania I noticed two boys pushing themselves down a dirt road on kick scooters. A friend pointed out that they couldn’t have bikes because an Amish council somewhere had determined that the chain and sprocket was an inappropriately high level of technology. It might break down community, too easily draw people away from their families and homes, from their roots. While this may seem a bit dictatorial it also suggests a sustaining ethic: community over convenience, meaning over marketability, wisdom over information.

It takes two hours to cross Illinois. In the darkness on the bridge over the Mississippi I try to remember a home does not belong to us, we belong to a home. On the Iowa side I see a smattering of lights, a yellow Caterpillar slowly crawls through the mud, its headlights illuminate a new subdivision. Even from the highway I can see the warm breath of steam rising from the fresh gash in the earth.

[MUSIC: Daniel Lanois, “Still Water” ACADIE (Opal, 1989)]

CURWOOD: Tom Montgomery-Fate teaches writing at the college of DuPage at Glen Ellyn, Illinois. He’s the author of “Beyond the White Noise”, a book of essays about living in the Philippines.

Coming home is the theme of this year’s annual Living on Earth storytelling special. That’s coming up in just two weeks. Our storytellers will share tales of how homecomings have influenced their lives. For example, Boston-based storyteller Jay O’Callahan recalls how gathering the clan in a huge blizzard turned his sister’s wedding day into a topsy-turvy affair.

O’CALLAHAN: Bong, bong, bong, bong. I woke 7 o’clock, grandfather clock, and I stretched, went back to sleep and I snapped on the radio. The announcer was saying, “It’s the biggest snowstorm of the century. This is a blizzard, ladies and gentlemen. Two feet of snow and it’s snowing, going to snow all day and all night. Everything is cancelled: Celtics, Bruins, college boards.”

I sprang out of bed and I looked out the window and there was two feet of snow and it was snowing hard. It was wild out there. Only the bluejays could move. Everything was transformed. By 8:30 and quarter of nine all the wedding guests, the Chicago guests, our neighbors, they were all tramping through the blizzard into our big front hall. “Going to be a wedding? How far is the church?” “A mile.” “A mile!”

CURWOOD: Find out if Jay’s sister makes it to the altar. Don’t miss our annual storytelling special two weeks from now on Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

News Follow-up

CURWOOD: Time now to follow up on some of the news stories we’ve been tracking lately.

Just as NASA was announcing that 2002 is the second-warmest year on record, the Canadian parliament voted to ratify the Kyoto Protocol to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Environment Minister David Anderson says Canada will urge citizens and businesses to adopt more energy-efficient technologies and practices. He also says that the decision puts pressure on Canada’s southern neighbor.

ANDERSON: It’s an indication that one of the countries within the North American Free Trade Agreement is willing to take these measures. We expect the United States to do likewise in the future.

CURWOOD: Now that Canada has given its okay, eyes are on Russia. If Russia ratifies Kyoto next year, as it has pledged, the Protocol will become international law.

[MUSIC UP]

CURWOOD: The oil tanker Prestige has leaked tens of thousands of tons of oil since it sank off the coast of Spain nearly a month ago. Now Spain and 14 other nations of the European union have banned from their ports single-hull tankers, like the Prestige, that carry heavy fuel oil. Peter Swift is managing director of Intertanko, international association that represents independent tanker owners. He says the ban goes too far.

SWIFT: It’s very much a global business and legislation at national level, at local level unilaterally is not a very desirable format for regulating the industry.

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, the EU is planning to set up safety zones to prevent ships that it considers “poorly constructed” from coming too close to the continent’s coastline.

[MUSIC UP]

CURWOOD: Southern California has established the first ban in the nation of the dry-cleaning solvent perchloroethylene. Owners of the region’s dry cleaners have until the year 2020 to do away with old machines that emit the toxic chemical, which is a probable human carcinogen.

Jill Whynot of the South Coast Air Quality Management District says the southern California ban is just the beginning.

WHYNOT: Based on the successful use of the technology here and in Europe I think it’s likely that more areas will enact a similar regulation.

CURWOOD: The state agency has set aside $2 million dollars to help dry cleaners make the switch to alternative technologies.

[MUSIC UP]

CURWOOD: And finally, even tree sitters can’t escape the dentist. John Quigley has been sitting in a 400-year-old oak tree for more than a month to protest development in Santa Clarita, California. When he recently chipped a crown on a granola bar and refused to abandon his tree, Dr. Ana Michel made a tree call. She quickly repaired the crown but warned that when Mr. Quigley finally does come down from his perch, the next place he’ll be sitting is the dentist chair for a root canal.

And that’s this week’s follow-up on the news from Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UP]

Animal Note/Wake-up Call

CURWOOD: Just ahead, how one Amazonian Indian tribe held off the oil companies with help from the son of a preacher man.

First this page from the animal notebook with Maggie Villiger.

[THEME MUSIC]

VILLIGER: It can be hard for night owls and early birds to live together in close quarters since their circadian rhythms are out of whack. But maybe compromise is possible, at least in the world of fruit flies.

Scientists know that social factors can affect biological clocks. Now researchers are narrowing in on how fruit flies can influence their buddies to wake up and get going. They observed that flies living in groups tend to be most active during the same periods, even when they’re kept in total darkness so they don’t know whether it’s night or day. Somehow the tiny bugs were communicating with each other and synching their internal clocks. Researchers wanted to figure out how, so they blew air through two habitats, one containing flies and the other one empty. Air that wafted through the vial full of flies, what the scientists called “fly air” was then pumped into the living space of flies who were living alone. Something in that fly air was able to match up the solo flies’ clocks with those of the group, even though they had no physical contact with each other.

Researchers think the flies use some kind of chemosensory cue that flows through the air and synchs up their clocks, and they suspect an olfactory signal is the trigger, since flies with a mutation that gives them a poor sense of smell were not affected by the so-called fly air.

That’s this week’s animal note. I’m Maggie Villiger

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Ekova, “Taksim” HEAVEN’S DUST (Six Degrees, 1998)]

Rolling Rainforest

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS]

CURWOOD: It’s Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The sights, sound, smell and feel of a tropical rainforest are neatly packed into a 48-foot trailer parked here outside the Brent Elementary School in Washington, DC.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS]

CURWOOD: This is the Rolling Rainforest, an ecological recreation of an equatorial habitat. It’s designed by the Discovery Creek Museum to transport school kids deep into the jungle without having to leave their neighborhood.

CHILD 1: We have antibacterial wipes. We have sunscreen…

CHILD 2: You have to be clean.

CHILD 1: And insect repellent.

CURWOOD: The kids are split into groups and they’re all pretending to be different kinds of scientists.

TEACHER: All right, entomologists, I want you guys to get ready right here.

CURWOOD: We’re following three young would-be entomologists who have received a letter requesting help from a Dr. Bea Von Trapp. The good doctor studied this rainforest ten years ago and she wants the kids to tell her how many of the bugs she identified back then are still around today.

A red-eyed tree frog in the Rolling Rainforest.

(Photo: Jeff Van Ness)

TEACHER: So the first step is what?

CHILD 2: Remove all three pitfall traps from the holes in the ground.

TEACHER: Exactly, so that’s your first step.

CHILD 2: Ew! (Laughs) It’s just a bug.

CHILD 1: Can I see it? See the tweezers.

CHILD 1: The first one we gotta identify. It’s green, has light green spots and six legs.

CHILD 2: Six legs?

CHILD 3: Let me see it again. Let me see the bug again.

CHILD 1: It looks like this.

CHILD 3: There it is.

CHILD 1: Can somebody hold the bug with the tweezers?

CHILD 2: I’ll hold it.

CHILD 1: Ew.

CHILD 3: It’s just fake.

CHILD 1: I know it’s a piece of plastic.

CHILD 2: Piece of plastic that looks real.

CHILD 1: Oh, we gotta pretend.

CHILD 3: Okay.

CHILD 1: What was the name of it?

CHILD 2: Starchichbidi something.

TEACHER: That’s a really hard name to pronounce. It’s scaribiadi. Can you say that?

CHILDREN: Scaribiadi.

TEACHER: And all those names are Latin names for the kinds of insects.

CHILD 2: It has one on this one too.

TEACHER: Yes, there’s a lot of different kinds….

[SOUND OF CHILDREN IN CLASSROOM]

TEACHER: Do you remember how many different bugs you guys found?

CHILD 3: Ten.

CHILD 2: Ten.

CHILD 1: I think twelve.

TEACHER: Twelve or so?

CHILD 3: We found ten.

TEACHER: Did you guys compare it to what the scientists found ten years ago?

CHILDREN: Yeah, it was 112-something.

TEACHER: Well, wait, the scientists ten years ago found over a hundred bugs?

CHILDREN: Uh-huh.

TEACHER: And you guys found around 10 or so?

CHILD 3: Yes.

TEACHER: What could have happened to the environment that made such a difference?

CHILD 2: It probably got eaten.

TEACHER: Maybe they got eaten. Who's eaten them?

CHILD 2: The animals. Bigger animals.

TEACHER: What else could happen?

CHILD 3: The amount of food.

TEACHER: What about the amount of food?

CHILD 3: Well some of the plants could have extinct.

TEACHER: That’s true, maybe their food source is leaving.

CHILD 1: Maybe they got drowned.

TEACHER: Actually now why does it matter? Why are we studying bugs in the rainforest?

CURWOOD: Indeed that question would come up again when our fledgling entomologists met their fellow kid hydrologists, ichthyologists-- that’s fish scientists, in case you wondered-- and soil scientists back in the classroom. The students talked about how the rainforest ecosystem is connected to the environment in their own schoolyard and how they rely on the rainforest for things like oxygen and medicine.

One question didn’t get answered though.

CHILD 1: Is there really a Dr. Bea Von Trapp?

(Photo: Discovery Creek)

CURWOOD: The Rolling Rainforest will visit 15 more schools in Washington, DC, before rolling on to New York and California next year.

[CLASSROOM TALKING]

TEACHER: Because there’s fewer species.

Related link:

The Rolling Rainforest at Discovery Creek

The Cofans of the Amazon

CURWOOD: The arrival of western cultures often spell disaster for native people in South America’s rainforests, but in at least one case contact between an American family and a remote Amazon tribe may have assured survival for that group and their rainforest home.

Sandy Hausman has our story.

HAUSMAN: The ballroom of the Hilton Hotel in Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, was arranged for a typical news conference earlier this year with folding chairs facing a podium and microphone.

[WOMAN SPEAKING SPANISH WITH MUSIC]

HAUSMAN: But the music playing overhead suggested this event would be different. And as some of the participants filed in, their fashions confirmed it. While government officials wore coats and ties, dresses and high heels, a group of native people arrived wearing crowns of green parrot feathers, jewelry made from jungle seeds or animal teeth, and colorful cotton tunics. Many had pierced ears and noses. A few were barefoot.

[APPLAUSE]

[R BORMAN SPEAKING KOFAN]

HAUSMAN: The trim, middle-aged man addressing the crowd was speaking the language of the native Cofan people. He wore traditional tribal clothes and had whisker-like marks painted on his cheeks. But he seemed an unlikely spokesman for the tribe; his skin was fair, his hair white, and his eyes blue.

[RANDY BORMAN SPEAKING KOFAN]

HAUSMAN: This man, Randy Borman, was the elected leader of a Cofan village and he was announcing the establishment of a new national park in the Amazon where, for the first time, ever the government would hire native people to serve as park rangers, armed with the power to evict trespassers. After more than three decades the Cofan had once again become masters of their own land, thanks in large part to Borman.

[CALLNG AMAZONIAN BIRDS]

HAUSMAN: This is Cofan country, one of the richest lowland rainforests in the world, 215 square miles of jungle along the Aguarico River in northeastern Ecuador. Here the foothills of the Andes and the Amazon basin meet, creating a complex community of plants and animals. It is also home to about a thousand people who hunt and gather in the forest while growing crops near their wooden huts covered with thick palm thatch.

In 1954 a pontoon plane touched down in the Aguarico carrying the American missionary Bub Borman. Speaking Spanish, a language known by a few members of the tribe, Borman explained that he and his wife Bobbie wanted to study the Cofan language and to translate the Bible so residents could read it. The villagers took Borman to see their chief.

BUB BORMAN: He invited us into the house and we sat down on a couple of benches and he sat in his hammock and he reached up behind his ear and pulled out his long cigar, reached in his pocket and he pulls out a Zippo lighter [laughs] and he lit his cigar with a Zippo lighter. And he says, oh by the way, he says, can you give me some gasoline to fill my lighter? [laughs]

HAUSMAN: It turned out that Shell Oil had preceded Borman by several years, introducing the Cofan to lighters, machetes, aspirin, penicillin and other products of the modern world. Shell concluded there was petroleum in Cofan country but getting it out would be too expensive, so its employees left, taking their medicines and tools away.

The chief thought the Bormans could bring those things back, so he welcomed the couple and they stayed for more than 25 years, raising four children in the village. Their oldest son, Randy, grew up as part of the tribe, speaking its language, learning to make a canoe and to hunt with a blowgun. Every few years he and his family went back to the states to raise money for their mission. But for Randy, the rainforest was always home.

R BORMAN: The kids learned to swim and then learned to handle the boats almost as soon as you can walk. We would play at hunting even when we weren’t actually hunting, with our blowguns or whatever. You know, it wasn’t like, oh we’re going to go camping in the wilderness, it was just something that, you know, you lived in and was taken for granted. It’s not something-- there was no big deal about it.

HAUSMAN: In 1973 Randy Borman left the jungle to attend college in Michigan. At that time the nearest town was eight hours away by canoe. But Western civilization was moving closer to his Cofan village. The oil companies were coming back. Now they had helicopters and other technologies that made it possible to drill in the jungle, to build pipelines and roads. Those roads brought land-hungry farmers from other parts of Ecuador. They cut down trees and laid claim to sections of the forest.

Cofan hunter Toribio Ayinda recalls his first encounter with one of those settlers.

[AYINDA SPEAKING COFAN]

VOICEOVER: We were on a trip upriver with the family and we ran out of food, so we were heading for my uncle’s house with our dogs, and on the way a dog started barking and chasing a deer. That’s when we saw the colonist. We tried to tell him this is our land but he got mad. He had a machete and threatened to kill us.

HAUSMAN: The Cofan family made a rapid retreat into the rainforest, bewildered and afraid. Oil exploration would also cause problems. Motorized canoes roared up and down the river while crews detonated explosives throughout the forest. The shock waves told express where oil could be found, but they also scared away animals. Drilling polluted the rivers, killing the turtles and fish, an important source of food for the Cofan.

Randy’s mother, Bobbie, says the culture was also contaminated as young people came in contact with oil workers from the city. Alcohol flowed freely, women were raped and theft became a serious problem. Until this time, stealing was almost unknown in this closed, egalitarian community.

BOBBIE BORMAN: I still remember the time that we forgot some money when we left the village. It was laying out on a table outside. Came back a month later and it was laying there. I mean, nobody would have even thought of stealing it.

HAUSMAN: And the tribe contends that increased pollution caused a dramatic rise in the number of cancer cases and birth defects. Randy Borman heard about these changes and decided to return to the village to help. He proposed that the Cofan move deeper into the jungle. And so in 1984 they established a new village called Zabalo. By consensus, Randy became its first chief. The people saw him as one of them, but because he understood western culture, could speak English and some Spanish, residents agreed Randy should go to Quito to lobby for the tribe. He was reluctant to leave the jungle but felt there was no choice.

R BORMAN: The Cofans were basically helpless and losing their lands quickly. I was much better off than my average friend there, as far as my knowledge of Spanish and the Latin culture and the whole Ecuadorian bureaucracy and all of this sort of stuff, but I was a little bit better, I had a better long-term vision and wasn’t quite as scared of it.

HAUSMAN: In the nation’s capital Borman built relationships with international environmental groups, journalists and government officials. Toribio Ayinda says he was an excellent advocate.

[AYINDA SPEAKING COFAN]

VOICEOVER: If Randy hadn’t helped, we’d be in a mess. Who would be in Quito having meetings? We don’t know anything about the ministry up there. Randy is there. We can come and see him, stay with him and have meetings. We need a leader. We are afraid of the Spanish people but if we have a leader, we will take a stand.

HAUSMAN: Those confrontations began in the jungle when the Cofans discovered drilling crews working without permits. The sight of hostile natives armed with blowguns, rifles and spears, led by an articulate American prompted the oil crews to leave and reporters to arrive. News coverage, sympathetic to the Cofan, filled Quito’s newspapers.

Finally Randy and other Cofan leaders went to the capital demanding access to government officials. They dressed in traditional clothes and face paint.

R BORMAN: Probably the only real weapon that the Cofans have is their color. We have very, very colorful dress, it makes good photos. And so I came up to Quito with three other leaders and our basic idea was to make a scene.

HAUSMAN: The scenes produced meetings and eventually agreements, culminating in the deal announced at the Hilton earlier this year. Drilling, logging and other exploitation of the Cofan’s land is now prohibited.

Borman is satisfied for the moment but worries about the future. To assure that protection of the land continues, he’s using a website to help the tribe advertise an ecotourism business.

[SOUND OF BOAT MOTOR]

HAUSMAN: Tourists arrive at the village by canoe, stay in huts with electric lights and warm showers powered by solar panels.

[WOMAN SPEAKING SPANISH]

HAUSMAN: They take tours down narrow jungle paths, learning about the forest plants and animals.

[WOMAN SPEAKING SPANISH]

HAUSMAN: If the tourist trade brings enough money, Borman says it could assure the community’s long-term survival.

R BORMAN: We’ve tried to develop the model of ecotourism as an alternate, saying that, you know, here we’ve got oil, this is what oil will produce during the next ten years, and then it’s gone. Meanwhile we’ve got ecotourism and it’s producing this much, and if you start looking at it over 50 years, we’re a lot better off than we would have been when the oil left this area.

[CHILDREN AND TEACHER COUNTING IN SPANISH]

HAUSMAN: The Bormans saw education as another key to the Cofan’s future and started this small school in a large open-air house. Young children read and recite Spanish at wooden desks painted pastel colors. Local people teach classes to the younger children, but the remote village has had trouble attracting good teachers for older kids. They must study in Quito, where they live with Randy and his Cofan wife, Amelia.

Two Zabalo community members learning how to operate a GPS device. They’ll use the GPS sstem to map their community lands and develop resource management plans.

(Photo: Dan Brinkmeier/The Field Museum)

The couple now spends much of the year in Ecuador’s capital with their three children and several more from the tribe. Amelia says Cofan parents are now beginning to understand the connection between schooling and survival.

[WOMAN SPEAKING SPEAKING COFAN]

A BORMAN: Many of the older people see no need for school, they just work the land and think the education they got in the jungle is all they need. But with all the changes in the area, with all the land problems and colonization, some of the parents now realize how important a really good education is so their children can grow up and live with the changes taking place in the world.

HAUSMAN: In sending children to the capital, the tribe runs a risk. Those kids might decide that they like city life. But Randy’s 14-year-old son Phillip and his friend, Hugo Lucitante, say they will go back to the village they love.

PHILLIP: Yes, it’s my home, Zabalo, just because I’m from there. I like it. It’s not like a city, it’s quiet, trees and not polluted like the city.

LUCITANTE: There is more stuff to do there. You don’t get bored that often. You always have something to do, and I like hunting, I like going fishing, going out camping.

HAUSMAN: And when the time comes to retire, Randy Borman says he too will return to that part of the rainforest he helped to save.

R BORMAN: I never had any desire really to live anywhere else. This Quito business is a hardship posed for me in every possible way.

Zabalo community members in front of the community research center.

(Photo: Dan Brinkmeier/The Field Museum)

HAUSMAN: Borman knows that over time the Cofan will change, that education, new technologies and experiences will have an inevitable impact on the tribe. But if they are to survive as a distinct people, Borman says their land must always be there to sustain and define their lives.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Hausman in Quito.

Related link:

Cofan website

[SOUND OF FLUTE PLAYING]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth.

Next week, the winter solstice is central to modern-day pagans who trace their practices and their environmentalism to traditions that predate Christianity.

FEMALE: To me there’s a strong connection between paganism as a religion and being active in service of the earth, because if you believe that the earth is sacred and if you really care about nature and love nature, then you can’t just sit by and let nature be destroyed all around us.

CURWOOD: But some call the new pagan rituals concocted and say they have nothing to do with original pagan celebrations.

It’s pagan practices, past and present, next time on Living on Earth.

And don’t forget that between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. That’s loe.org.

[ANIMALS CALLING IN RAINFOREST]

CURWOOD: Before we go, one last stop in the rainforest.

[ANIMALS CALLING IN RAINFOREST]

CURWOOD: In the Amazonian woods and marshes of southern Venezuela, Jean Roche made this recording, featuring the voices of no less than 13 different species of birds, mammals and insects.

[MUSIC: Earth Ear/Jean C. Roche, “Venezuela: Amazonian Forest and Marsh” (Sittelle, 1989)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Cynthia Graber and Jennifer Chu, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Jessica Penney and Liz Lempert. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Andrew Strickler and Nicole Giese. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our Technical Director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include: the National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of western issues, the Educational Foundation of America for coverage of energy and climate change, the David and Lucille Packard Foundation for reporting on marine issues, and the Welborne Ecology Fund.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth