January 31, 2003

Air Date: January 31, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

George W. Bush’s Environmental Report Card

View the page for this story

Two years have gone by since President Bush took office and promised cleaner air and water by the time he left office. At midterm, host Steve Curwood takes a look at the Bush Administration’s environmental record with journalist Mark Hertsgaard and the Department of Interior’s Lynn Scarlett. (11:00)

Health Note/Fashionable Filters

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a cheap and simple method to filter out cholera bacteria from contaminated water. (01:15)

Almanac/Battle of the Camels

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about camel wrestling. In Turkey, camel-mating season is underway and the male tendency to compete for mates is harnessed in this spectator sport. (01:30)

Save the Tigers

View the page for this story

Scientists gave wild tigers a terminal diagnosis in the early 90s, saying they could fend off extinction until 2000. Host Steve Curwood talks with conservation biologist John Siedensticker of the National Zoo and the Save the Tiger Fund about how they've helped tigers beat the extinction odds so far. (06:00)

Supermarket Compost

/ Dan GorensteinView the page for this story

A grocery store in New Hampshire is using a super-sized compost system to turn its waste food into fertilizer. Dan Gorenstein reports. (05:20)

Say No to SUVs

/ Arianna HuffingtonView the page for this story

We have comments from a recent talk given by columnist Arianna Huffington, cofounder of the Detroit Project. They've released controversial ads equating driving an SUV with aiding terrorists. They aim to make fuel efficiency and oil independence a national security issue. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Fighting Blazes

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on research taking place in space about how best to extinguish indoor fires. (01:20)

Chronic Wasting Disease

/ Eric WhitneyView the page for this story

An illness similar to mad cow disease is affecting deer and elk populations in the mid-west and western part of the U.S. There’s no proof yet that chronic wasting disease can affect people. But wildlife managers are worried that the disease could decimate deer and elk numbers, so they’ve taken some controversial measures to stop it. Eric Whitney reports. (12:00)

The Nature of Death

/ Tom Montgomery-FateView the page for this story

Given our complex language and reasoning abilities, do human beings understand more about death and mortality than other animals…or do we just think we do? Upon witnessing the death of several small creatures, commentator Tom Montgomery-Fate reflects on what we may not know about the ending of life. (03:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Mark Hertsgaard, Lynn Scarlett, John Siedensticker, Arianna HuffingtonREPORTERS: Dan Gorenstein, Eric WhitneyCOMMENTATOR: Tom Montgomery-FateNOTES: Diane Toomey, Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. An epidemic of the wildlife version of mad cow disease has Wisconsin hunters and biologists racing to contain the outbreak among deer, and no measure seems too extreme.

WHITNEY: Lee Arjuket is known informally as a head lopper, for obvious reasons. The blood smeared on his blue plastic coveralls indicates that he’s been busy. Archugit says he’s lost count of the number of animals he’s decapitated.

ARJUKET: Dozens, easily. Sometimes they bring in four, five, seven at a time and you just work through them all. So, I don’t know. I wouldn’t be able to tell you.

CURWOOD: The battle against chronic wasting disease. Also, President George Bush and the environment. It’s midterm and the grades are in.

SCARLETT: I’d give him an A, right up at the top of the list.

HERTSGAARD: I would give the president a D, bordering on D-.

CURWOOD: Mixed reviews for the president and more, this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth’s coverage of emerging science comes from the National Science Foundation.

George W. Bush’s Environmental Report Card

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. It’s midterm for the Bush White House and a natural time for us to assess the administration’s record on the environment.

Two years ago, the President promised that by the time he left office, the nation’s air and water would be cleaner and the ecosystem would be better off. In his latest State of the Union address, the President reiterated his strategy to reach those goals.

PRESIDENT BUSH: In this century, the greatest environmental progress will come about, not through endless lawsuits or command-and-control regulations, but through technology and innovation.

CURWOOD: Running, all-told, about three minutes and 20 seconds, Mr. Bush’s remarks on the environment were notable compared to his first State of the Union address, in which he only gave the environment a mention. Observers say the speech may be a signal that the environment is in store for a bigger play at the White House.

With me to talk about just how the president has lived up to this promise so far, and what lies ahead for the next two years, is journalist Mark Hertsgaard, whose critique of the administration’s environmental record appeared in The Nation magazine. Joining us is Lynn Scarlett, Assistant Secretary of Policy, Management and Budget for the Department of Interior.

And Lynn, we’ll start with you. In what ways has the president kept his environmental promises?

SCARLETT: Steve, the president has kept his promise in many, many, many ways. He committed before he was elected to taking care of our national parks. We were facing many billion dollars of backlog from neglect. We have committed hundreds of millions of dollars to restoring the parks, not only the facilities but natural resources. A lot of those dollars are going to fixing problems on streams, wastewater treatment facilities that were leaking and degrading the park areas.

In addition, of course, he talked about his Clear Skies Initiative. It’s an initiative that would reduce by 70 percent nitrogen oxide, sulphur dioxide and mercury omissions over the next ten years or so, 35 million ton reduction.

So, there you have on the natural resource side, and then on the pollution side, two major initiatives that show that environmental commitment.

CURWOOD: Mark, what’s your response to that?

HERTSGAARD: Well, I think the president has kept a number of his promises but they’d be different promises that I would cite. In particular, the president received, and the Republican National Committee received, 44 million dollars in contributions from the extractive industries in the year 2000 presidential campaign--the oil industry, the mining industry, the timber industry, chemical and electric utility industries. And we now see those former industries scattered throughout the Bush administration’s policy-making apparatus, and often making policy that affects their former industries. In particular, the administration has been hammered in the press pretty regularly about their policies on clean air.

They’ve essentially made voluntary a lot of these environmental initiatives, such as, they’ve excused the country’s dirtiest electric power plants from upgrading their pollution controls, made that voluntary. Stripping protection from 20 million acres of wetlands. And made in the national forests, made environmental impact statements optional. That kind of approach, which tends to rely on corporate good will and the idea that if we don’t over-regulate companies--as the president said in his State of the Union address, he’s against, what he calls, command-and-control regulations. The faith on the administration’s part is that corporations will do the right thing on their own.

CURWOOD: I’d like to turn now to energy. President Bush, when he gave the State of the Union address, specifically proposed 1.2 billion dollars for research into hydrogen technology. I infer from that he means fuel cell technology for vehicles. Lynn, what has he accomplished so far to promote cleaner cars?

SCARLETT: Steve, the president, in his State of the Union message, did talk about a major new technological investment to try and drive us to the next generation of clean vehicles. And that is very consistent with the overall vision of using innovation, incentives, working in partnership with Americans, both corporations and private citizens, to achieve results.

CURWOOD: Mark, what about this? 1.2 billion dollars--hey, that’s a piece of change for cars. How do you see this proposal fitting in with the president’s actions so far?

HERTSGAARD: Sure, hydrogen is a great thing. Clearly, the technology of the future. It’s very nice to see the Bush administration getting behind that. But today, right now, the cars on the road now, the Bush administration is doing little or nothing to increase the efficiency there. They’ve blocked significant increases in the fuel efficiency standards, along with Republicans in Congress. And instead, we’ve had a very tiny, tiny--I think it was 0.3 gallons--that are going to be reduced in terms of the efficiency for cars. Meanwhile, the administration is increasing the tax credits for people to buy SUVs.

CURWOOD: Mark, in the article you wrote for The Nation, you pointed to their policy on public lands. And essentially, you made it sound like you believe it’s a big giveaway to resource and energy extraction industries on the public land. Could you amplify?

HERTSGAARD: A lot of attention has been paid to the Bush administration’s desire to go drill up in Alaska, and it got the environmental groups very activated. I’m sure they raised a lot of money by waving around that threat, and it got Congress very animated, as well. But, the real big prize was elsewhere, and it’s almost to the point--I’ve heard some environmental strategists say, you know, that was a red herring up in Alaska. Get us focused on Alaska, and, meanwhile, the real prize is down there in the lower 48, the millions of acres of going into the Rockies and opening it up for oil and gas drilling and coal mining.

And, by the way, Steve, that includes drilling in national parks and some national monument areas. So far, those things have been stopped by lawsuits and by court cases. So, I think that is still playing out, literally, on the ground across the country.

On the so-called Healthy Forests Initiative, that was something that was crafted by a gentleman who worked as the vice president of the American Forest and Paper Association. And, not surprisingly, his proposal is let’s stop having environmental impact assessments for national forests, let’s make wildlife protection optional. I don’t know. I mean, I don't think that those are measures that if you asked the average American, do you think we should have an environmental impact assessment before we go cutting down timber in national forests--I think that’s a pretty popular mainstream idea with most Americans. So, that’s a real political risk, I think, that the administration is running.

SCARLETT: The Healthy Forests Initiative is actually, as its title suggests, about making forests healthier. I think the characterization of it is a little bit off-base. We had, last year, over 7 million acres burned. They burned--rather than the way natural, historic wildland fires burned, which typically burn just low across the ground and leave timber stands alive, or at least in a condition to regenerate. These are absolutely destroying the landscape.

Why this is occurring is because after a hundred years of management neglect, in some respects, we have forests that have densities of underbrush and very thin and scrawny trees that are 10 and more times historic levels. We utilized the scientific information that has been accumulated. In this case, we looked at over 3,000 different fuels treatment projects that have occurred over recent years across the nation, took those data and said, okay, let us use that information to be able to do additional like projects without duplicative paperwork and process and review.

So, this is about continuing to pay attention to impacts. And, where impacts conceivably will be high, we will continue to do environmental impact statements and the full sweep of protections that Mark refers to.

CURWOOD: We’re just about out of time. But before we go, let me ask you both, what grade would you give the president on his midterm environmental report card? Lynn?

SCARLETT: Steve, I’d give the president very good marks. I’d give him an A, right up at the top of the list. And I’d give him that A because, with his 45 billion dollar investment, it’s the highest ever given by a president towards environmental and natural resources protection.

I think the central challenge is, in fact, to get the message out that cooperative conservation--that partnerships--really is the pathway to progress for the future. And that we have a lot of those building blocks in place, the president investing enormous amounts of dollars and manpower and creativity to put those tools in place. People haven’t yet learned, and they haven’t yet heard the stories. Our biggest challenge is to tell those stories. To talk about the rancher that’s at the New Mexican border that’s preserving a grass bank, to talk about a rancher named Sid Goodlow that I recently wrote about who took on a very degraded piece of land and has absolutely done wonders restoring it.

Those are the stories we need to tell. That’s the challenge for the administration, saying we can do this together. And we’ve got to cut the umbilical cord in people’s minds that think that environmental progress simply equates one on one with, kind of, “have a regulation, have success.”

CURWOOD: Mark, how about it?

HERTSGAARD: Steve, I’m afraid I’d have to be a little bit more critical of the Bush administration, not being a spokesperson for them. If you look across the board, I think I would give the president a D, bordering on D minus. Because so many of the overriding challenges facing this country and, indeed, the world--we haven’t talked very much about the international aspects of this, but the United States is the 800-pound gorilla, especially on global warming, but on so many other issues. And we have shown zero leadership on that, and I think that will be looked back upon by history as a real dereliction of responsibility on the part of the United States. And I’m sorry to say that the Bush administration has not stepped up to the plate.

It’s not been a completely black record but it has been largely one that has been written of, by, and for, the polluting companies.

CURWOOD: Mark Hertsgaard is an environmental journalist and author of The Eagle’s Shadow: Why America Fascinates and Infuriates the World. Lynn Scarlett is Assistant Secretary of Policy, Management and Budget for the Department of Interior. Thank you both for taking this time with me today.

SCARLETT: My pleasure.

HERTSGAARD: Thank you, Steve.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder “La Luna En Tu Mirada” Mambo Sinuendo, Nonesuch (2003)]

Health Note/Fashionable Filters

CURWOOD: Just ahead, big bucks out of a big mess. A grocery chain converts food waste into cash.

First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: Cholera is a disease that continues to ravage developing nations. The waterborne illness is caused by a bacterium that thrives on plankton. Now, an international team of researchers may have found a cheap, yet effective, way to cut the incidence of cholera.

Working in Bangladesh, these scientists found that saris, the traditional dress of women in that part of the world, can effectively filter out plankton and therefore, cholera bacteria from water. Old saris work best since repeated launderings shrank the pore size of the cloth. And the sari had to be folded over eight times to make a fine enough filter.

Women in about two dozen villages were trained to place the folded saris over the tops of pots before collecting water. Another group of villages used nylon filters and a third control group used no filters. Women were also told how to rinse off the filters after each use, and field workers checked in on the villages every couple weeks.

After three years, the villages using nylon filters had reduced their cholera rate by 40 percent, but the sari cloth did even better, cutting the cholera rate in half. And in a poverty-stricken village, sari cloth has two other advantages: it’s cheap and readily available.

That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder “Patricia” Mambo Sinuendo, Nonesuch (2003)]

Almanac/Battle of the Camels

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: MC Sultan “Der Bauch” Arabesque, Gut Records (1999)]

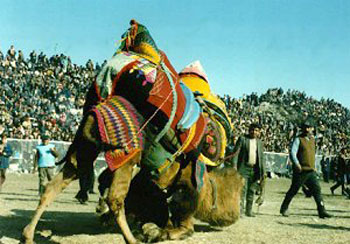

CURWOOD: It’s winter in Turkey, but the camels there are getting hot. That’s because it’s mating season and male camels are in the mood for love. And for a good fight, if necessary. An old tradition in Turkey is to watch the amorous Joe camels battle over their come-hither Josephines. An organized version of their courtship behavior is known as camel wrestling.

The sport originated in nomadic times, possibly as a competition between caravans. Wrestling camels, called Tulus, are bred for the sport. The Tulus wear bells and colorful fabrics as they parade through the streets of the wrestling field.

(Photo courtesy of Artemis Guest House)

To begin their match, a female camel struts on by. The two salivating males then begin pushing each other with their powerful bodies and necks. In the wild, these battles can get nasty, as camels have a mean bite. But in these games, Tulus wear muzzles for protection, and rope bearers, called Urgancis, stand ready to separate the animals if a fight gets too intense.

In the ring, whichever camel runs away, cries, or falls down loses, and the proud winner stands tall, basking in the adulation of the crowd and the object of his affections.

And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC FADES]

Save the Tigers

CURWOOD: In the early 1990s, biologists didn’t think wild tigers would last long enough to see the new millennium. But rather than giving up, scientists focused their conservation efforts in places where they felt they could make a difference. The result: the Save the Tiger Fund says today there are still healthy tiger populations in Russia, Nepal, Bhutan and southern India.

John Siedensticker is senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park and chairs the Save the Tiger Fund Council. John, let’s use the Russian far east as an example. Why did your conservation efforts there work out so well?

SIEDENSTICKER: Well, I think we had a variety of approaches. First of all, we supported work that was ongoing by the Wildlife Conservation Society, so we understood exactly what tigers needed to survive. We invested in, what are now called, the Amba patrol. Amba is a Russian word for tiger. These patrols were a new approach to kind of treat tiger poachers as a--in the same way you would treat insurgence. So, we got people who knew about conservation security involved and supported their efforts.

We launched, through local NGOs, a broad public awareness campaign of the tigers’ plight. And we’ve supported long-term monitoring so we know exactly how we’re doing. When we have problems, and sometimes there are tigers who get themselves into trouble with people, we have supported rapid response teams so that we don’t have a situation where you’re killing the wrong tiger, or many tigers, if there’s a tiger that’s in trouble. We go after the right tiger and then you make decisions about whether it can be translocated, or whether it can be rehabilitated, or whether it needs to be euthanized.

And so I think with all of this, it has given us the sense that the tiger has a fighting chance in the Russian far east now. And believe me, in the early ‘90s nobody gave what they called the Amur tiger or the Siberian tiger much of a chance.

CURWOOD: Now, in many of the places where tigers live there are also people. How do tigers interact with people when they’re sharing the landscape?

SIEDENSTICKER: Tigers are very specialized predators. They can’t live on small ungulates, and they don’t live on rabbits. They have to have big pigs, deer, and, in some cases, wild cattle. When they have adequate prey, they don’t get themselves, usually, in trouble eating people’s cattle, nor people. People have lived for years right next to tigers and it’s been--there’s this crunch for resources that leads to most of our problems with problem tigers.

CURWOOD: How does the Save the Tiger Fund work to influence those human-tiger interactions so that both parties come out unscathed?

SIEDENSTICKER: Well, let’s start with--the Save the Tiger Fund, we worked out kind of a formula that we call the five C’s. We need core areas where tigers are basically undisturbed. You need the connections between core areas, forests that connect core areas. The third C is you have to have the support of local communities. The fourth C is that, because tigers are top carnivores, wherever they live and wherever you manage to preserve them, they act as umbrella species for just about everything else that lives there. So, you preserve biological diversity in general. And then, the fifth C is we need communication so that we have a broad public awareness. We’re not going to save tigers without everybody’s involvement.

You need, also, the support of local communities. Local communities have to buy into the process. In the process of conserving tigers, you have to improve a lot of local communities and so, our effort has been to invest where we can in these buffer zone areas, in these connecting areas, in ways that local people come out of it ahead, too.

CURWOOD: Can you briefly tell me a success story here of conserving a tiger population in an area that you thought was very difficult?

SIEDENSTICKER: Yeah. I’ll go back to where I first went to Nepal, back in 1972. And the Royal Chitwan National Park was not yet quite declared. It had been a former hunting reserve. And it was just an area that was just this overall mix, like these buffer zone areas, and turned into cities, absolute commons, and the forests had been overrun with cattle.

And I was lucky enough to go back a couple of years ago to look at this, and there has been a marvelous transformation. And it was really exciting because here was a piece of land that had really taken on new and added value. Because they had become actually local guardians, if you will, of wildlife that lived in and around the reserve. As a result of their efforts, these buffer zones were changing into good wildlife habitat, as well as areas that were providing grass and firewood and places to graze their more select breed of cattle.

It was just an area that was working. It was working because we had local buy-in, people were doing it themselves, they were empowered. The money they were gaining from tourist revenues of looking at these areas were going into health clinics and into improving schools. Women were being trained to have vocations. It’s a model for what can be done to include local people in a formula that ultimately benefits tigers and their prey.

CURWOOD: Now, you’ve done fieldwork in Nepal, Indonesia, India. What’s it like to see one of these animals out in the wild?

SIEDENSTICKER: It’s always like a dream. When you see a tiger, they kind of come into your consciousness. Just as easily, they sort of fade away. There’s all that power and grace and beauty and it can explode at any minute, and it’s just a marvelous, splendid experience.

CURWOOD: Conservation biologist John Siedensticker is senior scientist at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park and chair of the Save the Tiger Fund Council. Thanks for taking this time with me today.

SIEDENSTICKER: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Greg Brown “The Tyger” Songs of Innocence & Experience, Red House (1986)]

Related link:

Save the Tiger Fund

Supermarket Compost

CURWOOD: Each week, the typical supermarket generates 15 tons of waste that winds up in the local landfill or incinerator. But in New Hampshire, one supermarket chain is testing a new technology to turn most of their organic waste into profitable compost, and it’s saving thousands of dollars in the process.

From New Hampshire Public Radio, Dan Gorenstein reports.

GORENSTEIN: Back behind the produce department, behind the deli, behind the bakery, a Hannaford Brothers employee sorts unsellable food. He cuts through items like plastic bags of frozen French fries and cartons of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. The food packaging is destined for the trash compactor, but the food itself is thrown into a wax-corrugated box.

Until recently, the store never sorted their trash. But that was before the Super C3. That’s the formal name for the store’s in-house composting system, but Hannaford employees call it Zola. That’s Greek for “ball of earth”.

BROWN: Hannaford wanted to have an everyday user name that was very easy and user-friendly.

GORENSTEIN: Ted Brown is Hannaford Brothers’ Environmental Affairs Manager. He spearheaded the effort to bring the new technology to the store. Each week, Zola turns seven tons of waste into compost. Here’s how:

The employee loads a box full of food waste onto a conveyor belt that carries it to a shredder. Paul Kerouac conceived of the Super C3 and runs Nature’s Soil, the company that sells the system.

[MACHINE SOUND]

KEROUAC: And the shredder slices everything to about the size of a piece of paper, but as thin as a piece of paper. The product goes through the shredder and then is auger-fed into this stainless steel drum.

GORENSTEIN: The drum is where the waste is transformed. It’s 40 feet long, eight feet wide, and can hold up to seven tons of material. Housed in a park-bench green container, it sits outside at the back of the store. Inside, there are three separate barrels.

KEROUAC: The product falls into the first barrel, and inside the first barrel we have the active bacteria already in there.

GORENSTEIN: Just like a simple backyard composter, the Super C3 uses bacteria to break down the waste, but the system here is considerably more high-tech, complete with a computer.

KEROUAC: The computer on board can control the moisture and the temperature and the oxygen, so this is the proper atmosphere for organic food waste to break down into another form.

GORENSTEIN: Kerouac says the computer controls the temperature inside the drum by occasionally signaling it to rotate. It’s kept at 131 degrees, hot enough to kill dangerous bacteria like e-coli, but cool enough to preserve the useful microbes. And after about a week, the waste is removed from the third, final compartment.

[MACHINE SOUND]

GORENSTEIN: Kerouac opens the drum door and loads some of the finished product into a bucket.

KEROUAC: You see these little, tiny balls, about an eighth of an inch and sixteenth of an inch in size? They look like little--like dirt, if you will. Just take a whiff of that if you will, smell that. What do you smell?

GORENSTEIN: It’s not a foul or a strong odor or anything.

KEROUAC: It’s like a more earthy smell.

GORENSTEIN: It’s not quite earthy, but definitely better than the odor that comes from grocery store dumpsters. The company says once it has enough of the compost material on hand, it plans on packaging and selling it as fertilizer at its stores. Hannaford’s Ted Brown says this system makes for good business. A Super C3 costs about $185,000. Brown says when compared to the cost of the usual way of disposing of garbage, the composter should pay for itself in about three years.

BROWN: You have to look beyond, and include all of the cost, which not only is the cost of the composter, which is a capital cost, but you also have to consider the tipping fee, the hauling fee, and those fees become a significant cost of doing business. Here in southern New Hampshire, particularly, and many other New England states, the cost of waste disposal has gone way beyond what would be considered a reasonable cost.

GORENSTEIN: But in other parts of the country, like the Midwest and South, where landfill fees are not as expensive, a system like the Super C3 may not be as attractive. Despite the economic sense it made to Hannaford Brothers, it didn’t necessarily make sense, at first anyway, to the company’s employees.

Mike Emory manages the produce department for the Nashua store. He doesn’t recycle at home, which could be the reason why his kids are so excited their dad has to at work.

EMORY: And they certainly are more into the “save the earth” than I am, and they’re loving this. No, they think it’s a great idea. And you know, I’m kind of in the converted file, because I thought it was a lot easier to just open that door and throw the stuff in there.

GORENSTEIN: Kerouac says his system comes closest to being what Emory is used to: opening the door and throwing the stuff out. And there are other conveniences. For instance, while one batch of waste is being broken down in the final compartment, a new one can be loaded in at the front end.

Kerouac says his company is designing a municipal size composter that could process one thousand tons of waste a day. And there’s also a plan to develop, what he calls, a home composting vessel

For Living on Earth, I’m Dan Gorenstein in Nashua, New Hampshire.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of western issues.

Say No to SUVs

HUFFINGTON: I want to thank all of you for leaving your SUVs at home, except that guy who arrived in the Hummer with that bumper sticker saying, “Honk if you hate the ozone layer.” Talk to me later. [laughter]

CURWOOD: That’s Arianna Huffington, syndicated columnist, ex-Republican and former sport utility vehicle owner. And you may have heard that Ms. Huffington wants everybody else to give up their SUVs, too. It’s a message she’s been touting in media ads and public appearances.

She recently brought her campaign to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and we have a few excerpts from a talk she gave at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. We’ve also thrown in a few examples of her TV ads that have been banned by a number of major broadcast outlets.

HUFFINGTON: I just did a column in which I parodied the administration’s drug war ads. You remember those in which they equate taking drugs with terrorism? And I said in that column, what about the much more credible link of equating gas-guzzling cars with funding terrorism, and I ended with a rhetorical question. Would anybody be willing to pay for a people’s ad campaign to jolt our leaders into reality? And I thought nothing more of it until the next morning I was confronted with 5,000 e-mails from people saying, where do I send my money?

FEMALE: I helped hijack an airplane.

FEMALE: I helped blow up a nightclub.

MALE: So what if it gets 11 miles to the gallon?

FEMALE: I gave money to a terrorist training camp in a foreign country.

MALE: It makes me feel safe.

MALE: I helped our enemies develop weapons of mass destruction.

FEMALE: What if I need to go off-road?

MALE: Everyone has one.

MALE: I helped teach kids around the world to hate America.

FEMALE: I like to sit up high.

MALE: I sent our soldiers off to war.

MALE: Everyone has one.

FEMALE: My life, my SUV.

HUFFINGTON: The explosion of SUVs is a case study of the collision, the collusion between corporate America and Washington. Because if you look at the millions of dollars that Detroit spent to defeat the McCain-Kerry bill that would have increased fuel efficiency standards last year, you’ll realize why it didn’t happen.

[MUSIC]

CHILD: This is George. This is the gas that George bought for his SUV. This is the oil company executive who sold the gas that George bought for his SUV. These are the countries where the executive bought the oil that made the gas that George bought for his SUV. And these are the terrorists who get money from those countries every time George fills up his SUV.

HUFFINGTON: Right now, the question is how do we turn this into a voting issue, not just an important issue, but a voting issue, so that politicians begin to do something about it?

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Arianna Huffington’s latest book is called “Pigs at the Trough: How Corporate Greed and Political Corruption are Undermining America.” For her next reform crusade, Ms. Huffington says she is setting her sights on how to eliminate polling from the political process.

HUFFINGTON: Our public policy at the moment is being run by a small unrepresentative minority of bored and lonely Americans who have nothing better to do at dinner than talk to strangers for no money. [laughter]

Related links:

- The Detroit Project

- Arianna Huffington's website

Emerging Science Note/Fighting Blazes

CURWOOD: Just ahead, a deadly campaign against a deadly disease. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Cynthia Graber.

[THEME MUSIC]

GRABER: Astronauts on the current space shuttle mission are testing a new firefighting system that battles blazes with a fine-water mist instead of harmful chemicals or large quantities of water. Bromine-based compounds had been used to attack fires chemically, especially in places like computer rooms where water would cause damage. But they’ve been banned because they damage the ozone layer. Aside from being non-polluting and less damaging, water mist prevents fires from expanding in two ways. It removes heat, and as it evaporates, it replaces oxygen that would otherwise fuel the fire.

The mist system is being tested in space because it’s easier to observe the interaction between a flame and water in low gravity. On Earth, lighter, hotter air rises, creating air currents that pull in oxygen and feed the fire. But in the micro-gravity of the shuttle, these air currents are greatly reduced, making it easier to isolate the effect of the water mist on a flame.

In the shuttle experiment, a water mist is released onto a flame that burns inside a tube. Scientists hope these tests will help them determine the best water concentration and water droplet size needed to suppress fires with the least damage.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Cynthia Graber.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC FILL: Ry Cooder “Drume Negrita” Mambo Sinuendo, Nonesuch (2003)]

Chronic Wasting Disease

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

About 10 million Americans hunt deer each year. But these days, an epidemic among deer has hunters worried that their sport will never be the same.

Chronic wasting disease is a cousin to so-called mad cow disease. It’s spreading faster than biologists predicted and has the potential to devastate wild deer populations. There’s also a concern that it could infect humans, as well.

There’s no known treatment or cure for chronic wasting disease. And wildlife managers are being forced to take radical and controversial steps to control it. Eric Whitney reports from disease hot spots in the Rocky Mountains and Midwest.

[CLICKING SOUND]

WHITNEY: It takes a special kind of person to do work like Elizabeth Williams does, especially at 8:00 in the morning.

WILLIAMS: What I’m doing is cutting the ribs. That’s so I can get in to look at the thoracic cavity.

WHITNEY: Dr. Williams is a University of Wyoming pathobiologist, a scientist who studies the cause of animal deaths. Today, she opens up the body of a dead mule deer found by the side of the road.

WILLIAMS: Must’ve been hit with real tremendous force. You can see how the liver is just all fragmented. That’s part of, I presume, being hit by something pretty big.

WHITNEY: There’s no murder mystery here. It’s obvious that this deer was killed by a car. But tissue samples from this animal offer a glimpse into the overall health of the state’s entire deer heard, so Dr. Williams carefully collects small pieces of the animals organs for further analysis.

This type of routine surveillance work is how Dr. Williams discovered a new and enigmatic wildlife illness called chronic wasting disease, or CWD. She says at the time, 25 years ago, it didn’t seem like a big deal.

WILLIAMS: It wasn’t anything that special, believe me. We find new things all the time, and this just happens to be one that’s kind of gone forward, and in retrospect has turned out to be something maybe more important than we thought initially. But there wasn’t anything that special.

WHITNEY: That’s because CWD had only been observed in a handful of captive deer at a research facility in Colorado. Inexplicably, deer there began behaving erratically, drooling and losing interest in food until they wasted away and died. Since then, the disease has been found in 11 states and two Canadian provinces. And the more biologists have looked for CWD, the more they’ve found.

But, even so many years after its discovery, some very basic questions about the disease still remain unanswered. For instance, scientists have no idea where CWD came from, nor are they even sure exactly how the disease is transmitted.

WILLIAMS: Somehow, the agent gets out of the animal. It gets into the environment, and then, presumably, there’s enough of the agent present that a susceptible animal can pick it up. We don’t know very much about the dynamics of that. We don’t even know for sure if that happens, but we think it does.

WHITNEY: The agent that scientists believe causes CWD is called a prion. It’s not a living organism itself, like bacteria or a virus, but a malformed protein molecule. Prions are incredibly resilient. They’ve been shown to remain infectious in the outdoors for more than a decade. They’re resistant to chemical disinfectants and even the high-temperature autoclaves used to sterilize surgical instruments. And once they infect a deer, Dr. Williams says, they’re 100 percent lethal.

WILLIAMS: We’ve looked at lots of deer and we don’t recognize any genetic resistance. And animals don’t develop antibodies, so they don’t develop the kind of immunity to these diseases that you would like to a viral disease or a bacterial disease. It’s an entirely different kind of response and, unfortunately, none of the research shows that in deer there's any resistance to CWD.

WHITNEY: Exactly how prions work is poorly understood. Scientists most often find them in brain tissue, where they appear to cause adjacent healthy proteins to become twisted and misshapen, too. Slowly, the brains of victims become riddled with microscopic holes.

Last fall, in an effort to better understand the disease, wildlife managers in Colorado launched an unprecedented effort to examine tissue from the brains of thousands of deer across the state. That meant asking deer hunters to bring the severed heads of the animals they killed into collection stations. They were kept in walk-in refrigerators like this one in Denver.

MALE 1: This is actually where we keep the heads.

MALE 2: How many you think you got in there?

MALE 1: We had 50 turned in this morning and probably at least another 30 since then, so probably 70 or 80 heads today. While we didn’t get as many heads as we expected, I think we’re pleased with the kind of data that we are getting.

WHITNEY: State officials expect the data from this growing collection to tell them not only where the disease is most prevalent, but also how fast it is spreading. Because there’s no known treatment for, or vaccine against CWD, wildlife managers here are trying to control it by drastically reducing the size of deer herds in diseases hot spots. In the most extreme case, this means killing more than half the deer in a 2,000-animal herd.

MALMSBERRY: When people think about what Colorado represents, they think of the mountains, they think of skiing, but they also think of big game herds.

WHITNEY: Todd Malmsberry is a spokesman for the state’s Division of Wildlife. He says the culls are justified in order to stave off the devastation of those big game herds, and what they mean to Colorado culturally and economically.

MALMSBERRY: We can’t think of anything more irresponsible right now than to simply sit on our hands and do nothing, and watch this disease progress through the western United States and actually potentially through all of North America.

WHITNEY: Colorado’s culling strategy has drawn criticism from a broad spectrum of citizens, but it pales in comparison to what’s being done in Wisconsin.

[SAW SOUND]

WHITNEY: Tucked away in a ravine near the village of Black Earth is what’s officially known as a wildlife registration area. Most people, however, call it a head lopping station, because this is where Wisconsin, like Colorado, is collecting deer heads to test them for chronic wasting disease.

Lee Arjuket is known informally as a head lopper, for obvious reasons. The blood smeared on his blue plastic coveralls indicates that he’s been busy. Archugit says he’s lost count of the number of animals he’s decapitated.

ARJUKET: Dozens, easily. Sometimes they bring in four, five, seven at a time and we just work through them all. So, I don't know. I wouldn’t be able to tell you.

WHITNEY: This station is in the middle of Wisconsin’s CWD hot zone, a two-county area in the Southwest part of the state that so far is the only place the disease has been observed here. Because it appeared less than a year earlier, wildlife managers think they have a shot at eradicating the disease. Their strategy is to kill every potential carrier within 400 miles of where CWD was found. That’s 25,000 deer: bucks, does, fawns, everything.

Killing this many animals to control a disease is one of the most radical acts ever undertaken by wildlife managers in the U.S. They say the action is justified because Wisconsin’s deer population density is far greater than Colorado’s. That means CWD has the potential to spread much more rapidly in the Midwest. The massive herd reduction has been endorsed by leading wildlife biologists, like Dr. Thomas Yuill, Director of the Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin.

YUILL: In situations like this, it’s prudent to run the risk of reducing the population more than is necessary, than underestimating the relative transmissibility and not quite reducing the population enough to break that chain of transmission.

WHITNEY: Scientists also point out that killing 25,000 deer in Wisconsin will hardly make a dent in the state’s estimated population of a million and a half animals, a number some say is already too high. But Wisconsin’s disease-control strategy is not without its critics in the scientific community.

SOUTHWICK: It’s almost an archaic procedure to control a disease by killing the organisms that might contract the disease.

WHITNEY: Charles Southwick is Professor Emeritus of Environmental and Population Biology at the University of Colorado. Now retired, he has studied animal population dynamics for 50 years.

SOUTHWICK: I think Wisconsin’s program is unrealistic. And I would still say to them, go in and do selective culling of sick-looking animals. Get this population down to the point where it’s in reasonable balance with its habitat, but don’t try to kill every animal in a given area.

WHITNEY: Wisconsin officials say that just killing sick-looking animals won’t work. It takes years for deer to begin showing symptoms of CWD. They say targeting only deer that look sick virtually guarantees that a reservoir of disease will remain undetected within the herd, spreading to more animals. But because of the huge genetic diversity within the species, Southwick continues to believe that there may be some deer out there with genetic resistance to CWD. If that’s true, mass killings would eliminate the very animals that would be the basis of a new, healthy deer herd.

Southwick’s theories remain the minority opinion. Most wildlife biologists continue to support actions like those being taken here in Wisconsin. But killing every deer inside 400 rugged square miles of dense woods is no small task, even in a state where some schools still take a break for deer season and couples have been known to plan pregnancies around the annual fall ritual.

This hunter, who gave his name as Mike, says he doesn’t plan to take more deer than normally allowed.

MIKE: No, no. Take a couple of them, sure, I’ll help out. Sure. I won’t go crazy with it, though.

WHITNEY: For generations hunters have been taught that it’s wasteful and wrong to shoot more deer than your family can eat. But this year Mike says he won’t be bringing any venison home at all.

MIKE: No, I’m going to dump this out. It’s got the wife scared also. I don’t know.

WHITNEY: A lot of hunters say their wives don’t want them bringing deer home this year. That’s because CWD is similar to so-called mad cow disease, which has been proven to cause a lethal infection in people who eat contaminated beef. No studies have ever linked chronic wasting to human illness, but Wisconsin and Colorado are letting hunters and their disease hot zones know whether the animal they shot tested positive.

Many discount the health risk and eat the meat, but the Centers for Disease Control recommend against it. Worried that disease fears would keep hunters home this fall, Wisconsin took the unusual step of actually encouraging people to go hunting, with radio ads like this one.

RADIO AD: Freeze em, test em, fry em. I ain’t afraid of no twisty little prion here. Keep fighting CWD. And it won’t take long. There’ll be a flash of white, and there it was…gone. The Wisconsin D&R, CW-free in 2003.

WHITNEY: The campaign appears to have worked. Official say hunter numbers were only off by about 10 percent.

[LAUGHTER]

WHITNEY: Kevin Hayvey and his buddies are among those who came out. Tonight, they’re having steaks and beers after a day of hunting. Hayvey says they were disappointed when they learned that their favorite hunting spot fell within Wisconsin’s CWD hot zone. They’re hunting here again anyway, but Hayvey doesn’t like to think beyond this year.

HAYVEY: Because I was like, okay, if they’re going to kill every deer in a spot, like I say, I’ve been hunting for 26 years. I’m like, what am I gonna do? Where am I gonna go? I guess once you get locked into a spot, locked in with a group of guys you’ve been with and all of the sudden it could be all like sort of yanked out from your feet. I was really depressed.

WHITNEY: The goal of killing all the deer in Wisconsin’s hot zone has proven difficult to achieve, even with strong support from hunters. Only about a third of the 25,000 animals targeted were brought in. In response, the state is allowing two extra months of hunting in the hot zone. It’s also sending state and federal sharpshooters into the area who will work at night using bait, spotlights and guns equipped with silencers to kill the animals.

For Living on Earth, I’m Eric Whitney in Black Earth, Wisconsin.

The Nature of Death

CURWOOD: Human beings care a great deal about how they die, about who is present at the moment of death, about the ceremony afterwards and about what happens to the body. Commentator Tom Montgomery-Fate has these thoughts on how other creatures might understand their own demise.

MONTGOMERY-FATE: Last week, I woke to find two mice sitting on the workbench, noisily munching on opposite sides of a ripe Red Haven peach. Each had chewed away a tablespoon or so of the flesh and left a tiny pile of fuzzy peach skin gnawings.

The next day, I bought cheap wooden traps, smeared them with chunky peanut butter, and set them on the trails of excrement the mice left along the floor. The two neck-cracking snaps I heard that night felt like success, not cruelty.

In “Leaves of Grass” Walt Whitman claims “A mouse is miracle enough to stagger sextillions of infidels.” I agree intellectually, but what of reality? Two turn into ten, and then ten into fifty in a month or two. It gets crowded. Recently, I agonized over a fleeing mouse that somehow jumped a foot off the ground into the crack between the hinged end of the door and the jamb just as I was leaving. I nearly cut him in two. Grossly pinched in the crack, his bulging black eyes pleaded with me, but it was too late. I killed him quickly with a brick, but felt his desperate gaze all day.

Last month, I witnessed the death of another small creature. This time, though, it seemed holy rather than tragic. While pumping my bike along two-lane blacktop, I noticed a glint of yellow on the road ahead. I coasted up near the ditch to find a goldfinch lying in the gravel, upright. The feathers were bright and clean, no evidence that it hit a windshield or been raked by a crow. A perfect specimen. Yet it was not flapping or trying to escape, and its eyes were closed. It lay in the gravel softly breathing. I got closer, put my face down near its feathers hoping to find out what was wrong, and then this: its eyes opened. Two shiny black beads peering at me for several seconds. I felt it sensed that I was there and had used all of its energy to confirm its suspicion, to see what I was. Then the eyes closed, the breathing slowed and stopped. The goldfinch died and I had no idea why--disease, poison, or hopefully, a natural end.

I’m still wondering about that open-eyed instant of connection, about being the last living thing that an animal was to see. Does dying alone matter to creatures that live by instinct rather than reason? Perhaps the goldfinch didn’t even notice me in its last moment but was looking beyond at the empty sky, the dried rustling weeds, the stark silhouette of a maple tree, sensing not aloneness, but belonging.

[MUSIC: Sigor Ros, “Svefn g englar” Agaetis Byrjun, Pias America (2001)]

CURWOOD: Tom Montgomery-Fate teaches writing at College of DuPage in Glen Elyn, Illinois and is author of “Beyond the White Noise,” a book of personal essays about living in the Philippines.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, a year-long investigation by a journalist around the world reveals how three global corporations gained control of the water supply to more than 300 million people.

CARTY: If you think of the American water market, about 85 percent is municipally owned. Faced with investment in infrastructure, these small municipalities really can’t cope with the level of investment required. And so some form a private-public partnership with an injection of capital with the financial muscle of large companies like ourselves. It’s probably the only way for them.

CURWOOD: Is water the oil of the 21st century? Next time on Living on Earth.

And remember that between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. That’s loe.org.

[GROWLING: Earth Ear “Primal Voices” The Dreams of Gaia, Earth Ear(1999)]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with this segue between two very earthy and very resonant sounds from the natural world. Jonathan Storm recorded and mixed these primal voices for his CD “Planet Earth”.

[SOUNDS OF ANIMALS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Maggie Villiger, and Jennifer Chu, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Jessica Penney and Liz Lempert.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutraro and Nathan Marcy. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include: The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service.

ANNOUNCER: This NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth