May 23, 2003

Air Date: May 23, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Whitman Resigns

View the page for this story

EPA administrator Christine Todd Whitman has tendered her resignation to President Bush. National Journal writer Margie Kriz talks to host Steve Curwood about the move. (05:30)

Dangerous Crossing

/ Kent PatersonView the page for this story

When the nation's security alert level goes from yellow to orange, traffic along the U.S. border with Mexico slows to a dead stop. Kent Paterson reports from El Paso, Texas that the result is intense air pollution in a small area, and it's a problem for people who have to spend time there. (06:00)

Emerging Science Note/Microbing Michaelangelo

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports that bacteria might help protect Europe’s statues and buildings. (01:15)

Almanac/Shine a Light

View the page for this story

This week, facts about lighthouses. The feast day of Saint Venerius, the patron saint of lighthouse keepers, is in May. (01:30)

The Politics of Population

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

Many environmentalists agree human population is a major source of strain on the planet. But it’s often missing from the environmental agenda. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum reports from Washington on the state of the population conversation. (07:00)

Verichip

/ Angela SwaffordView the page for this story

Reporter Angela Swafford goes beyond the call of duty when she merges herself with a machine and gets an implanted microchip. (03:30)

Letters

View the page for this story

We dip into the mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (01:30)

()

Environmental Health Note/Saving Cassava

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

For people living in the tropics, cassava is one of the most important foods. But if it's not properly processed, eating it can lead to cyanide poisoning. Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new, genetically-modified cassava plant that's cyanide-free. (01:15)

WTO Showdown

View the page for this story

Agriculture is currently the biggest stumbling block in World Trade Organization negotiations. Edward Alden, Washington correspondent for the Financial Times of London, explains the implications to host Steve Curwood. (05:40)

Saving Forests, One Bow at a Time

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Instrument bows are made almost entirely from one type of wood, and that wood is endangered in its native Brazil. Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on the bow-makers’ efforts to help save the trees, and save their craft. (09:45)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Margie Kris, Edward AldenREPORTERS: Kent Paterson, Cynthia GraberCOMMENTARY: Angela SwaffordNOTES: Cynthia Graber, Diane Toomey

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

It used to be that discussions about the environment often included talk about population. But as the U.S. faces a population explosion through immigration, environmental advocates tend to avoid the subject.

CHRISTIAN: When you start to talk about immigration policy-- reducing the level of immigration or stabilizing the U.S. population--you are accused of racism, elitism …

CURWOOD: It’s the politics of population. Also, Christine Todd Whitman ends her uneasy stay as head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by resigning, and heading home to New Jersey.

KRIS: I think she had one foot out the door when she came here. I don’t think she really liked the idea of being the fundamental regulator; she liked being in the administration.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and the world’s first bionic reporter, this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and HeritageAfrica.com.

Whitman Resigns

(Photo: EPA)

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. (Photo: EPA)

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Christine Todd Whitman will leave her post as Environmental Protection Agency administrator at the end of next month. In her letter of resignation to President Bush, she cited the desire to return to New Jersey, her home, and the state she governed before joining the administration. Margie Kris covers the environment and energy for the National Journal in Washington, and she joins us now. Margie, Christine Todd Whitman cites “family reasons” for stepping down now. What’s your take on her announcement and timing? KRIS: Well, she’s been rumored to be leaving ever since she came, just about. I mean, she seemed to have had one foot out the door most of the time she’s been in that position. She seems to have been unhappy. I don’t think she had the clout she thought she was going to have when she came in. She’s been criticized for her policies in the administration from the Left, and the Right doesn’t like her either. She had hoped to get a position as either commerce secretary or a trade representative, or something like that. Those positions are not opening up. As I said, I think she had one foot out the door when she came here. I don’t think she really liked the idea of being the fundamental regulator; she liked being in the administration. Now she’s decided it’s time to go. CURWOOD: Which way do you analyze this? Did she jump or was she pushed? KRIS: Oh, I think it was a mutual decision. She has been considering this for some time, quite clearly. So I think that it was a moment in time when they were saying, look, either you stay for the whole period of time until the elections are over, or else you leave now, giving us the time to make an appointment and get through that before the elections really kick in. I also think that she’s not a nitty-gritty policy person. She isn’t as curious or interested in the real detailed information about how environmental policy is made. She’s kind of a governor, “big picture” person. And I also think that the White House people and some of the conservatives have not been happy that she has been reticent on pushing some of the Bush administration policies. CURWOOD: What are some of the issues that really were quite difficult for Christine Todd Whitman at the Environmental Protection Agency? Where did she get into trouble? KRIS: Well, from the very start, there were two things that happened in the first year or so. One was her going overseas and bragging that President Bush was going to regulate carbon dioxide, mostly from coal-fired power plants. And she came back from that trip to Europe and found out that no, indeed, he was not going to. He had decided not to go forward with that proposal. Also, shortly after that, she was working on a regulation that had come to her from the Clinton administration to control the amount of arsenic in drinking water. And she said, well, they’re going a little bit too far on this; they’re regulating it too strictly. I’m going to ease up on that. There have also been some more recent issues that have come up about her asking for favored treatment when she is traveling around the country and around the world--wanting certain radio stations on, wanting to be driven by coffee places and favorite bookstores, and being called “Governor” instead of “Administrator.” Some of those things make her look a little bit elitist, as opposed to being kind of this everyman regulator that people at the EPA tend to sort of seek that image. CURWOOD: Now, as Christine Todd Whitman’s resignation becomes yesterday’s news, let’s look ahead to tomorrow’s news--her replacement. Who do you see on the short list there? KRIS: You might start with Linda Fisher, who is now the deputy administrator at EPA. Linda was with EPA for years, then became a lobbyist at Monsanto. The most interesting one is David Strues who is in Florida right now as the chief regulator for environment there, for Jeb Bush. He also has an inside line because he is the brother-in-law of Andy Card, who is chief of staff at the White House. There is Governor John Engler of Michigan who environmentalists are not crazy about his record when he was in place. There is Josephine Cooper. Josephine Cooper is now the lobbyist for the automobile industry, but she had a good reputation when she was at EPA years ago. For all I know-- my prediction is that it is going to be somebody who is not on this list. CURWOOD: In this administration, does it matter who is in the top spot at the Environmental Protection Agency? Some would say the White House calls most of the shots there. KRIS: I think you are right about the big picture stuff. It’s coming from the White House. It’s coming from the economic people there, from the Energy Department. But I think on a day-to-day basis, and as far as morale within the agency, it depends a lot on who is the administrator. And in this department, I think that Whitman has not been as strong. She has not been a great leader. She has not been somebody who has instilled a lot of confidence that she has been able to put forward the best arguments that the EPA staffers can make and really fought for their issues. So, yes, policies are not going to change dramatically, but there might be a subtle underpinning to it that brings some strength to EPA. CURWOOD: Margie Kris is an environment and energy writer at the National Journal. Thanks for filling us in, Margie. KRIS: Thank you.

Dangerous CrossingCURWOOD: Each time the U.S. Department of Homeland Security declares a Code Orange terrorist alert, long lines of traffic build up at the U.S.-Mexico border as inspectors are required to open each car hood and trunk. But in El Paso, Texas, the traffic jam is more than an inconvenience. Federal agents say the heavy buildup of exhaust fumes is endangering the health of workers and the public. Kent Paterson has our story. [MAN SPEAKING SPANISH] PATERSON: Jose Juan Aguilar roams the Santa Fe bridge between El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, hawking foldout sunshades for cars. Aguilar says long lines are good for business but make him feel bad, especially during the warm months when smog accumulates. [MAN SPEAKING SPANISH] PATERSON: With traffic waits sometimes reaching two hours or more during Orange Alerts, the issue of bad air at the bridges is becoming more urgent for officials on both sides of the border. Alma Leticia Figueroa is the director of the Environment Department in Ciudad Juarez. FIGUEROA: [SPANISH] What we have here is a really small ecosystem, and the emissions here are hurting the healthy people who have to spend eight hours or more here for their work. People who work in Immigration, in Customs, people who are selling on the bridge--they are the ones most affected. PATERSON: Figueroa is also irked that many of the dirty vehicles on the bridges are out-of-compliance U.S. junkers that end up being sold to low-income commuters from Juarez. Brad Gaetzke is the chief steward in El Paso for the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents several hundred U.S. Customs employees who staff the bridges. Gaetzke says his members get headaches and feel lousy, especially since Orange Alerts have become more frequent since 9-11. They filed 150 grievances over the amount of time spent on the bridge at inspection stations. GAETZKE: If it’s like in the middle of July, and there is no wind, and the temperature is about 100 degrees, and cars are overheating, of course, you are going to have the heat. Plus, you are going to have the carbon monoxide coming off of that. Plus, sometimes we also have impurities that blow in from Mexico when they are burning paper and things like that. PATERSON: The United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) looked at the air around El Paso bridges shortly after 9-11. They have found Customs Inspectors were exposed to carbon monoxide in peak exposures lasting 30 seconds or less that were a cause for concern. When the measurements over an eight-hour shift were averaged, however, the amounts were not considered excessive. The same study noted that bridge pedestrians were exposed to carbon monoxide on a short-term basis, up to nine times the eight-hour OSHA health standard. CLOUSE: Well, the problem, obviously, is the number of vehicles operating on the bridges that are at very low speeds, typically at speeds in stop-and-go conditions which really emit the largest amount of pollution. PATERSON: Archie Clouse directs the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s El Paso office. Clouse says one of the main concerns is carbon monoxide. CLOUSE: It displaces oxygen from the blood and can cause anywhere from just drowsiness to death, and all the symptoms in between. So, typically, with carbon monoxide, we’re talking about an acute concern. PATERSON: In El Paso, the dangers of carbon monoxide couldn’t be more acute for one family. Michael Widfeldt is El Paso’s assistant fire chief. Widfeldt describes what happened on October 21st, 2001 when post-9-11 traffic tie-ups had the family of Lara and Francisco Valenzuela stuck for almost two hours on an international bridge. WIDFELDT: They thought that their two children were asleep in the back of the pickup truck they were driving. When they got home they tried to wake them up to put them to bed, and that’s when they realized there was a problem. PATERSON: Thirteen-year-old Erica and six-year-old Danielle were unconscious. WIDFELDT: The two children that were in the back of the pickup were not breathing. Efforts were made to try and revive them. They were transported to the hospital and they were pronounced dead at the hospital. PATERSON: It wasn’t the bridge traffic alone that caused carbon monoxide to build up in Francisco Valenzuela’s pickup. The exhaust system was faulty. But the delay was a contributing factor. Officials say they don’t have the full picture on air pollution at border crossings. In part, that’s because air monitors are often located a distance from these bridges and don’t register peak emissions. Experts could point to no comprehensive health studies focused on air quality at the international bridges. Gerardo Tarin is the director of environmental regulation in Ciudad Juarez. Tarin contends that traffic backups haven’t worsened the overall quality of the local airshed, but he says more needs to be done to reduce the exposure of customs workers and other people on the bridge to very localized or micro-pollution. TARIN: [SPANISH] We’re working with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the Mexican secretary of Public Health. We’re preparing a study that looks at heavy diesel vehicles on the bridges and how they affect the people that work there, like Customs agents. PATERSON: Meanwhile, officials recommend that drivers crossing international bridges in these times of increased security keep their cars well-tuned for everybody’s benefit. For Living on Earth, I’m Kent Paterson in El Paso, Texas.

Emerging Science Note/Microbing MichaelangeloCURWOOD: Coming up: immigration pressures and the response of the environmental movement. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Cynthia Graber. [MUSIC: Science Note Theme] GRABER: Picture a European city with limestone sculptures adorning streets and buildings. Now, imagine what the city might look like without these works of art. They are threatened by pollution. Acid rain that gets in the pores of the stone eats away at the grains. Previous attempts to protect statues by coating them clogs those pores, trapping moisture inside. When the moisture froze, the statues cracked. Now, two scientists in Spain have turned to some microbes for a solution. They knew that one type of common garden bacteria exudes the mineral calcium carbonate which is similar to the stone found in the statues. So, they took pieces from the cathedral in Grenada, Spain and immersed them for 30 days in a bath containing the bacteria. At the end of that month, the microbes had worked their way half a millimeter into the limestone where their mineral deposits acted as a bio-mortar, coating and strengthening the original grains. Researchers hope to one day spray threatened sculptures or wrap them in bacteria-soaked cloth. But they say they’ll proceed cautiously. Previous attempts to use bacteria to cure acid rain erosion left statues slimy or discolored. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Cynthia Graber. [MUSIC] CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Erroll Garner “Tea For Two” That’s My Kick and Gemini - Ocatve (1994)]

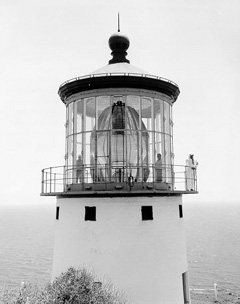

Almanac/Shine a LightCURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. [MUSIC: Manfred Mann “Blinded by the Light” Best of Warner Archives - Warner (1996)] CURWOOD: Many a mariner has scanned the horizon for the beam of light that signals the presence of dangerous shoals. Some of these sailors may have offered up a prayer of thanks to St. Venerius, the patron saint of lighthouse keepers. May holds the Annual Feast Day of Venerius. No one is quite sure how this Catholic Bishop from Milan became associated with the solitary folk who shine a light on the dangerous out-croppings of the seas. Lighthouses have been around for ages before Venerius died in the fifth century. The most celebrated, of course, the 40-story plus lighthouse of Alexandria. One of the seven wonders of the ancient world, it marked the Egyptian port with a beacon that reflected fire of the giant mirror. To help ships navigate during the day, some lighthouses are painted with distinctive patterns. At night, lighthouses send out different flash patterns called their characteristic. Sailors can consult a chart to figure out their position based on the pattern of alternating light and darkness, and the different colors of light they see.

|

The Boston Harbor Light on Little Brewster Island was the first lighthouse established in America. It was first lit on September 14, 1716. (Photo: USCG)

The Boston Harbor Light on Little Brewster Island was the first lighthouse established in America. It was first lit on September 14, 1716. (Photo: USCG)  The Makapuu Point Light on Oahu Island, first established in 1909, has a lens that's more than eight feet across and can beam out a light that can be seen for 28 miles. (Photo: USCG)

The Makapuu Point Light on Oahu Island, first established in 1909, has a lens that's more than eight feet across and can beam out a light that can be seen for 28 miles. (Photo: USCG)

Floriano Schaeffer is one of a number of Brazilian bowmakers growing Pau Brasil trees. (Photo: Arcos Brasil)

Floriano Schaeffer is one of a number of Brazilian bowmakers growing Pau Brasil trees. (Photo: Arcos Brasil)