Missouri River water levels are at the center of a controversy where opposing court rulings may force the Army Corps of Engineers to change the way it manages the river. (Photo: American Rivers) Missouri River water levels are at the center of a controversy where opposing court rulings may force the Army Corps of Engineers to change the way it manages the river. (Photo: American Rivers) |

A district judge in Washington, D.C. has ordered the Corps to reduce the amount of water it sends down river each summer, so that three endangered species have a better chance of survival. But the Corps says it can’t do that and run barge traffic at the same time. Joining me is Bill Lambrecht, a reporter with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, who’s writing a book about the river’s history and politics.

Bill, before we dive into a discussion of the interests involved in these cases, tell me what does the Missouri look like in the upper reaches in Montana where the river starts?

LAMBRECHT: One starts at the headwaters of the Missouri River: the Madison, the Gallatin, and the Jefferson Rivers, all named by Lewis as he stood on a bluff looking westward. The water there runs clear and cool and sparkling. I was just on it a couple weeks ago, in the face of some very high bluffs. There are a couple dams there, but throughout Montana it’s much like it was when Lewis and Clark saw it. The river changes markedly as you get into the Dakotas where it’s been dammed up quite heavily. It’s a series of huge lakes. And then in the lower third, the lower stretch, it has becomes more or less a barge canal. It’s much narrower, with these rock-armored banks. It runs swift – sometimes eight miles an hour. If you put your canoe in Kansas City, you’ll be in St. Louis in no time, Pippin.

ROSS: At the center of this is that along the way that you just described, the Army Corps of Engineers have a series of dams that are really integral to the court case. How do those change the river and influence this case?

LAMBRECHT: Well, those dams came about, most of them, after the 1944 Flood Protection Act, which was aimed at just what is says, flood protection, but also to create this great navigable river. That never really happened. The barge traffic is very slim downstream. And there has been a great debate in recent years about whether we should continue operating these dams as we do.

ROSS: There are a number of competing interests up and down the river that have come to a head, of course, in this courts case. One is endangered species. The main argument in the most recent case was to make the flow simulate a more natural river to help protect three endangered species. How would a change in flow help protect animals along the river?

|

|

|

| Unnaturally high summer river flows submerge river sandbars where the least tern (left) and the piping plover (right) build their nests. (Photo: American Rivers)

LAMBRECHT: Well, Pippin, take this summer for instance. The Fish and Wildlife Service and conservation interests have argued that where the flow is slower and lower, two of the endangered species, the piping plover and the least tern, could more easily nest and wouldn’t have to worry about high waters washing away their nests and the chicks that are in them. It would also be of some benefit to the pallid sturgeon, that prehistoric looking fish that has all but disappeared in the Missouri River. The recent debate has been focused primarily on the low flow, that’s because the conservation interests realized there was a great drought and it wasn’t time to key on the high flow, which was something else that has been recommended. But were there a higher flow in the springtime, that could recreate the backwaters, the oxbows – all the habitat that has been destroyed over the last half century in the operation of this dam-managed river.

ROSS: But the low summer flows could ground barge traffic, right? I mean, how significant is barge transportation?

LAMBRECHT: Well, that’s exactly the case. There was an analogous fight last summer, where the river was closed down a while to protect these species. I rode up on the first tow boat pushing a lot of barges, and it was a fairly harrowing trip, with a lot of fear of bouncing on the bottom and destroying the barges. And what it has done is it’s made the barge industry viewed as an increasingly undependable mode of transportation. If the flow is lowered, there’s no question that the barge traffic would stop on the Missouri River for much of the summer. And that has been a source of great irritation to that industry, although it’s not very big, and it certainly never reached the proportions that the Corps of Engineers and its promoters anticipated several decades ago.

Barge on the Missouri River (Photo: American Rivers) Barge on the Missouri River (Photo: American Rivers) |

ROSS: But what we have going on is the property owners, the barge navigational aspect, and the recreational aspect along the river is pretty much up in arms over this.

LAMBRECHT: Absolutely. The river has a finite amount of water upstream. In addition to the whole species debate, there’s a big fight over who gets the water. I was just upstream recently in South Dakota where at some of the lodges the boat ramps look like high dives. The water is down 20 feet or so. Then you get downstream where I’m from, in the St. Louis area. There is a great need for water, not just for the barges but for the municipalities, for power plants. So there’s a great underlying fight for water here, no question.

ROSS: I realize that the Missouri is your purview and turf, and I kind of hate to put you on the spot this way, but this smacks of awfully broad national, if not global, implications about water.

LAMBRECHT: Well, I think that’s the case. There’s also, I think, some case law – some precedent here – with regard to the Endangered Species Act. That isn’t quite an enduring law but there are a lot of sentiments in Congress that I see about changing that. There’s a debate here about the needs of creatures versus the needs of people. So this may be among the several cases in the country right now, where we sort out this question of who’s to benefit from our rivers.

ROSS: Bill Lambrecht is a reporter with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Thank you so much for speaking with us, and good luck with the story.

LAMBRECHT: Great to be here.

Related link:

American Rivers Back to top

ROSS: After weeks of delay and debate, the Senate Judiciary committee has given the green light to one of the Bush administration’s most contentious nominees for a federal judgeship, William Pryor. His nomination now heads for a full Senate vote. In response to Pryor’s and other judicial nominations, the environmental community has started to weigh in on the future balance of the courts. Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports.

Alabama Attorney General Bill Pryor Alabama Attorney General Bill Pryor |

CHU: The U.S. Federal Appeals Courts are second only to the Supreme Court in handling judicial decisions. The judges who sit on these benches are lifetime presidential appointees. Meaning that whoever is confirmed to the 13 circuit courts will far outlast the tenure of the president.

NEECE: This is a public official who would be wielding influence for 40 or more years, interpreting the constitution of the land. This is as important a decision as the president and the senate ever makes.

CHU: Ralph Neece is president of the national social justice group called People for the American Way. Keeping track of judicial nominations is a high priority for the group, since protection of its members’ civil, abortion and labor interests hinge increasingly on the federal appeals courts. That’s also been the case in recent years with environmental issues, and Neece’s outfit has started recruiting environmental groups in its expanding coalition of judicial watchdogs.

NEECE: In recent months and recent years, the environmental organizations have become more and more of an important key player in the effort to save the courts. And without question, the next 16 months could determine what the environmental law and what a lot of the laws will be for the next two or three decades.

CHU: Glenn Sugameli is an attorney with Earthjustice, a national environmental law firm in Washington, D.C.

SUGAMELI: What we’re seeing is that the balance on a number of the courts is tipping against the environment.

CHU: Sugameli and others have been lobbying against several of Bush’s nominees, whom they say could threaten and repeal long-established environmental laws. At the top of the list is William Pryor, a 41-year-old attorney general for Alabama. He’s nominated to the 11th circuit, which oversees Florida and Georgia, as well as Alabama. Sugameli believes that Pryor’s environmental record indicates how he might make decisions as a federal judge.

SUGAMELI: Bill Pryor was the only state attorney general to file a legal challenge to the constitutionality of key Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act protections. He also testified to Congress that it was an invasion on the states to enforce the clean air act in cracking down on expansion of coal-fired power plants and utilities that harm downwind states. He also has a record of favoring corporations and failing to crack down on corporate pollution in Alabama.

CHU: Among Pryor’s staunchest supporters is Republican Senator John Cornyn of Texas, who at a judiciary committee hearing, voiced the view of many from his party.

CORNYN: I believe that Mr. Pryor fully understands the different role of an advocate, as attorney general in a courtroom representing his state, and the role he would be called upon to play as a federal judge. That he understands the difference between his personal preferences and beliefs, and what the law is.

CHU: In addition to Pryor, environmental groups have also come out in opposition to Miguel Estrada to the D.C. circuit, whose nomination has been blocked by Senate Democrats. Among other concerns, environmental groups believe Estrada has too limited a public record to gauge his qualifications in environmental ruling. These groups also charge that Caroline Kuhl, if confirmed to the 9th circuit in California, would limit representation of parties claiming injury by industrial pollution.

Supporters of the president’s judicial nominees argue that such concerns are merely a type of litmus test for advocacy groups. Sean Rushton is executive director of the Committee for Justice, a group formed in 2002 specifically to support the president’s nominees.

RUSHTON: It’s only relatively recently that this kind of politicization of the judicial confirmation process has become the norm, where activist groups look at how is he on issue x y and z, and if he doesn’t have a history of ruling exactly as we want, we’re going to oppose him.

CHU: However, environmental groups contest that that’s not the case. Again, Glenn Sugameli of Earthjustice.

SUGAMELI: The people who’ve been nominated for judgeships by President Bush have not been our favorite. But we have not opposed a number of those because we think they’d be basically fair. But what you don’t want is a judge who will not give you a fair hearing and unfortunately there are such judges.

CHU: The Senate will vote on whether to confirm William Pryor, as well as other judicial nominees, in the next several months. For Living on Earth, I’m Jennifer Chu in Washington.

[MUSIC: Yo La Tengo “Danelectro 3” Danelectro Matador Records (2000)]

ROSS: Just ahead: Hot ads for a warming planet by cool people. Hollywood responds to global warming. You're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: The Postal Service “Such Great Heights” Give Up Sub Pop (2003)]

Back to top

ROSS: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Pippin Ross.

[MUSIC: Various Artists “Geitaslålten” The Devil’s Tune Grappa Musikkforlaoz (1998)]

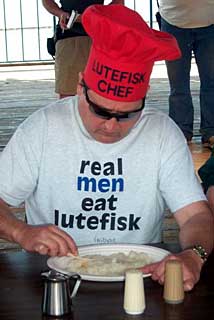

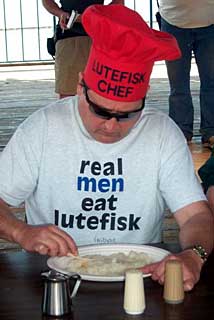

ROSS: During the dog days of summer, Scandinavian-Americans across the midwest hold festivals to evoke the taste, smell and agony of a Nordic Christmas with a centerpiece dish called the lutefisk. Lutefisk comes from the words lute –“to wash in lye” and fisk – “fish.”

| |

A participant at Viking Fest in Poulsbo, Washington (Photo: Alf Erickson)

Sound suspicious? It should. Lye is a caustic compound found in soap, oven cleaner and Drano. Dried cod is soaked in it for up to two weeks before it’s boiled down and served as a Jello-like entree. Sound gross? You betcha. Don’t-cha know. Especially the lutefisk’s overpowering odor – a putrescence that is part decomposing fish, part harsh chemical stench. As one popular Scandinavian “carol” goes: A participant at Viking Fest in Poulsbo, Washington (Photo: Alf Erickson)

Sound suspicious? It should. Lye is a caustic compound found in soap, oven cleaner and Drano. Dried cod is soaked in it for up to two weeks before it’s boiled down and served as a Jello-like entree. Sound gross? You betcha. Don’t-cha know. Especially the lutefisk’s overpowering odor – a putrescence that is part decomposing fish, part harsh chemical stench. As one popular Scandinavian “carol” goes:

“O Lutefisk, O Lutefisk, how fragrant your aroma.

O Lutefisk, O Lutefisk, you put me in a coma.”

Scandinavians confront this meal with feelings that range from love and duty to disgust. One writer describes his experience with “a foul and odiferous goo, whose gelatinous texture and rancid oily taste are in spirited competition to see which can be the more responsible for rendering the whole completely inedible.” Inedible though it seems, Americans belly up to the table and consume more than 600,000 pounds a year. At summer eating contests across the country, contestants race to slide as much as eight pounds of lutefisk down their gullets. Now that’s hard to swallow.

And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC FADES]

Back to top

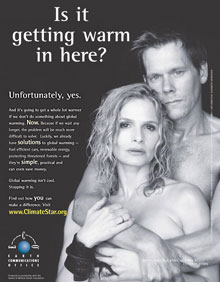

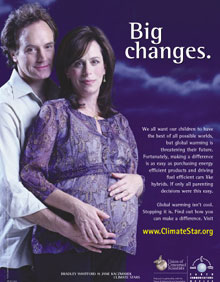

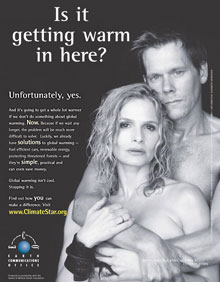

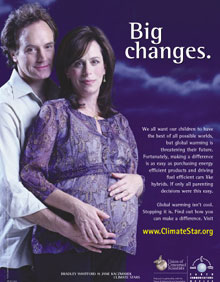

ROSS: The science-heavy, politically charged topic of climate change is not what you expect to read about in TV Guide, Sports Illustrated, People, or Seventeen. But climate change may be moving out of the clouds and onto the magazine rack where, sweat beading on his forearm, actor Kevin Bacon warns, “Six Degrees Can Make A World of Difference.” Bacon, his wife and actress Kyra Sedgwick, film icon Susan Sarandon, the West Wing’s Bradley Whitford and CSI’s Jorja Fox, are among the cast featured in new ads in America’s most popular magazines. Joining me to take a closer look at the campaign is Jonah Bloom, executive editor of Advertising Age magazine.

Hi, Jonah.

BLOOM: Hi, Pippin, how’s it going?

ROSS: Good. I’m looking at, right here, the hot – and I’m not talking temperature-wise – glossy ad. It’s got a shirtless Kevin Bacon with his arms around Kyra Sedgwick. She’s also topless. Her arms cover her, but her hair – it definitely looks like she’s been you know, shall we say, engaged in some sort of activity.

|

|

BLOOM: Yeah, they both look a little sweaty, don’t they?

ROSS: Yeah, yeah. And she’s even got something leather wrapped around her wrist.

BLOOM: Yeah, I was interested…I don’t really know how that relates to global warming, but there’s certainly something going on there.

ROSS: So, the copy says, “Is it getting warm in here?” So I guess the first question for you is, is this in your opinion a good ad?

BLOOM: You know what? I actually, I was kind of pleasantly surprised by these ads. A lot of ads for, sort of, causes and for non-profit organizations can be kind of dull. And I thought these were very clever. They employed celebrities in a way that was going to catch attention. As you’re sort of intimating there, there’s obviously, like, a sexual overtone, which again always gets people’s attention. And there are some clever catch lines as well. I mean, there’s the “six degrees can make a world of difference,” sort of punning off the Kevin Bacon six degrees of separation. I thought they were kind of clever and right for the consumer magazine audience that they’re aiming for.

ROSS: Well, you know, they’re sexy and glossy and all that stuff. But it’s interesting, because these ads are really warning people about sea level rise, drought, stranded plants and animals. I mean, how surprising is it that these messages are infiltrating really mainstream magazines?

BLOOM: Well, I mean, I think that given Senators Lieberman and McCain are really trying to push this issue, it’s not that surprising that they’re trying to bring it to a broader public attention, and really force the issue up the political agenda, if you like, or higher up the political agenda. You know, it’s something, it’s one of those things where probably a kind of intellectual minority, if you like, have been concerned and been worried about it. But it’s maybe not been a mainstream issue for your average consumer, not something they’ve worried so much about as the economy, and how much money they’ve got in their pocket, and whether they’re going to be employed next week. And this is obviously trying to change that, and make them realize this is something that is happening to them.

ROSS: And the magazines, it turns out – big shocker – are providing the ad space free. The celebrities are doing it as volunteers. How unusual is that?

BLOOM: You know, there are plenty of Hollywood personalities who do care about causes and, of course, whilst we don’t want to be too cynical about this, it’s never a bad thing for the celebrity concerned to show that they’re someone who cares about social causes. It helps them with a certain part of their audience and gives them a certain type of credibility, as well.

ROSS: I’m just curious – how much does a page in People or Wired cost?

BLOOM: Probably very different rates there. You know, in People you’re looking at a hugely popular weekly. In something like Wired you’re looking at a big glossy monthly. So it can be very different depending on the type of publication. But you’re probably looking at upwards of $25,000 for a page in either of those publications.

ROSS: Okay, so does this ultimately signal to you that the public discussion and interest on this subject is evolving, it’s growing?

BLOOM: I don’t know whether it yet signals that. You’d like to think that the public interest and discussion is growing. But, obviously, the ads tend to predate the discussion that comes after them. But certainly, the fact that they’re now burrowing down not just to the, necessarily, The New York Times reader, who’s going to plow through a long article which talks about the science of, for example, global warming, but they’re also going for the People reader. You know, that tells you that they’re trying to broaden the audience for this, and you’d imagine that this would be a relatively successful campaign in achieving that.

ROSS: Well, thank you so much for being with us, Jonah.

BLOOM: Not at all, not at all, a pleasure.

ROSS: Jonah Bloom is executive editor for Advertising Age magazine. To see photos of the celebrities featured in the “Climate Stars” ad campaign go to our web site: livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org.

[MUSIC: Nelly “Hot in Herre” Nellyville Universal (2002)]

Related links:

- See more ads from this campaign

- Climate Star website Back to top

ROSS: In the 1970s, Simon Paneak, a Nunamiut Eskimo, built what would be the last inland Eskimo kayak. The University of Alaska Museum in Fairbanks commissioned it. Paneak was the last Nunamiut who knew how to build one. But 30 years later, that kayak is falling apart. Now the builder’s son, Roosevelt Paneak—after years of concerted effort—has persuaded the museum to let his community try to repair the boat. Amy Mayer visited the workshop in Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska—home of the Nunamiut—and prepared this report.

[PEOPLE SPEAKING INUPIAT]

MAYER: Simon Paneak’s 20-foot long kayak has arrived back in Anaktuvuk Pass, where he made it. This arctic village is 350 air miles from Fairbanks. The kayak’s sitting atop a plywood crate in a room usually used to fix snowmobiles. Word’s gotten out that the boat is here—and that a load of fresh strawberries arrived with it. So people stop by, feel the old skins and learn about how their ancestors hunted.

[PEOPLE SPEAKING INUPIAT]

MAYER: Lela Ahgook examines the stitches on the kayak’s caribou skin seams. Soon, she and two other women will begin covering the frame with new skins. The old ones are cracked and broken—as are some of the boat’s white spruce ribs—the result of being in too dry a room for a time.

AHGOOK: You have to leave a piece from one side, and you sew it on both sides to put it together.

MAYER: Young Nunamiut have never seen Nunamiut kayaks before. Most say they didn’t know kayak hunting existed in their culture. Even the village museum—named for Simon Paneak—doesn’t have a kayak. Years ago, women and children lured caribou into a lake and then the men paddled after the swimming animals with spears ready. Technology changed that equation. Jack Williams describes how the Nunamiut hunt today.

WILLIAMS: We use rifles to shoot it, caribou, we use skidoos to go places and I think that’s it.

MAYER: The Nunamiut hunted with kayaks for the last time in 1944, when there was a wartime ammunition shortage and they temporarily returned to the old way. Few elders remember that last great hunt. And only Nunamiut over 30 could have watched Simon Paneak building this kayak. That’s why Roosevelt Paneak encouraged—and then pushed—museum curators to send his father’s kayak back to Anaktuvuk for the repairs. He’s a humble man, but curators rave about his tenaciousness and his commitment to the project. Paneak says fixing the kayak here is good for the community.

PANEAK: This way they can be right with it and actually touch it and see craftsmen or craftswomen at work.

MAYER: One of those craftswomen is Lela Ahgook. She says that although she and the others have never made a kayak, they have made caribou skin mukluks.

AHGOOK: Just like waterproof rubber boots when we make them. So we know a little bit what we’re going to do, I think.

MAYERL: The first task is to remove old babiche—or caribou skin rope—from the boat’s cockpit. Ahgook says it’s not easy.

AHGOOK: I think this was sewn when it was wet. It’s hard to pull out.

[RUSTLING NOISES]

MAYER: Soon, though, they’re ready to remove the old, dry, cracked skins.

[CRINKLING, SOUND OF SKINS BEING REMOVED]

MAYER: The three women continue admiring the skins. These old pieces are all the instructions they have. Ruth Rulland and Molly Ahgook talk in Inupiat about the challenge and Lela Ahgook paraphrases.

[WOMEN SPEAKING INUPIAT]

AHGOOK: She says it’s going to be hard to put it together because we never see them do it, so we just have to do what we see.

MAYER: Angela Linn is the ethnology and history collections manager at the UA Museum. She hitched a ride to Anaktuvuk on a cargo flight with the kayak. Linn says it’s unusual to actually remake museum pieces.

LINN: Replacing them, rather than just stabilizing them, is a really controversial issue. And so the fact that it was never really used, and the fact that it was commissioned specifically for the museum really changed my mind and convinced me that this was the right thing to do.

MAYER: Roosevelt Paneak agrees. He’s been a bundle of stress getting this project organized. But now that it’s progressing nicely, he pauses briefly to reflect on his father.

PANEAK: I think he would be happy that something like this was being undertaken. And bringing it back here, had he been here, I think he would be very happy that there is an interest in such a craft.

MAYER: When the boat is ready, the last inland Eskimo kayak in Alaska will take a new test ride. And then it will return to the climate-controlled galleries of the Fairbanks Museum, where curators hope it will be preserved without need of future repairs. The damage brought this boat back to its birthplace. And that means another generation of Nunamiut Eskimos will remember how their great-grandparents hunted.

For Living on Earth, I’m Amy Mayer in Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation environmental information fund. Major contributors include the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. Support also comes from NPR member stations and Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR’s coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR president's council. And Paul and Marcia Ginsberg, in support of excellence in public radio.

Back to top

ROSS: Not everything gets a second chance in life. As part of our continuing series “A Gap in Nature,” author Tim Flannery chronicles the rise and fall of creatures who are no longer with us.

[AMBIENT MUSIC]

FLANNERY: The islands of the West Indies were once home to five unique species of giant rice rats, the oversized omnivorous rodents flourishing in the steamy island swamps. The Martinique giant rice rat, a splendid black and white creature the size of a housecat, was the largest and most abundant of these species.

| |

Until a century ago, these animals were a common sight on Martinique’s sprawling coconut plantations. The rats were strong swimmers – a talent which might have helped them survive the wrath of plantation workers, who did their best to exterminate them. They hated the rice rat for its relentless destruction of their crops.

Until a century ago, these animals were a common sight on Martinique’s sprawling coconut plantations. The rats were strong swimmers – a talent which might have helped them survive the wrath of plantation workers, who did their best to exterminate them. They hated the rice rat for its relentless destruction of their crops.

Rice rats also happen to be a popular dinner dish and became a regular feature on restaurant menus in Martinique. But cooking a giant rice rat was a rather laborious process. In order to reduce its musky odor, the hair had to be singed off and the body left in the open air overnight. It then had to be boiled in two different batches of water, before it would be declared edible.

The final demise of the Martinique giant rice rat came rather abruptly, and unlike most species in the 20th century, man had nothing to do with it. On the 8th of May, 1902 at precisely 7:52 A.M., the Mt. Pelee volcano erupted, with a ferocity that devastated the entire island. The town of St. Pierre, a bustling metropolis of 30,000, was engulfed in ash and superheated volcanic gas. Only a single human survived, a condemned prisoner who was being held in a dungeon deep underground. He was eventually pardoned – perhaps for his miraculous survival – and joined Barnum and Bailey Circus to tour the world as “the lone survivor of St. Pierre.” The rice rats were not so lucky. They evidently perished, either in this volcanic eruption or the ones that followed later that year. For the Martinique giant rice rat was never heard from again.

ROSS: Tim Flannery is author of “A Gap In Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals.” To see a picture of the rice rat, and hear other segments in our series, go to our website: living onearth.org. That's livingonearth.org.

Back to top

ROSS: Coming up: a journey to the bottom of the Black Sea. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Cynthia Graber.

[EMERGING SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

GRABER: If the animated film character Nemo were a real fish, he might not stay a boy forever. That’s because Nemo is a clownfish, and clownfish can change sex at different points in their lives. Scientists have been on to this phenomenon for years. They also knew that clownfish can change size, even after reaching adulthood – but they didn’t know why. Now one scientist says he has an answer.

Peter Buston of Cornell University spent a year in Papua New Guinea, diving four to six hours a day tracking clownfish. Buston noticed that within each group of fish that live together in a sea anemone, there are two breeders, the female being slightly larger than the male. Then there are three or four non-breeding clownfish, each getting progressively smaller down the hierarchical line. Buston discovered that when one of the breeders dies, each fish moves up the ladder. If the female dies, the breeding male grows larger and becomes a breeding female. Then the largest non-breeder morphs into a breeding male.

Buston says the little clownfish stay little because if they grew large, the breeders might see them as a threat and force them out of the protective anemone. So, as far as clownfish go - sometimes it’s better to be a small fish in a big pond.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science, I’m Cynthia Graber.

ROSS: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Wes Montgomery “Movin’ Wes’, Pt. 1” Compact JazzPolygram (1987)]

Back to top

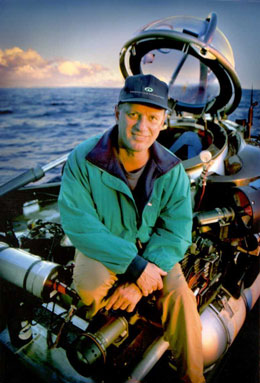

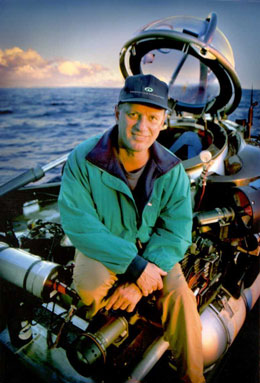

ROSS: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Pippin Ross, and coming up: The other English Potter. But first: Dr. Robert Ballard found the Titanic, PT Boat 109, and the Bismarck, to name a few on his long list of underwater finds. This week, the oceanographer and self-described “undersea explorer” is leading an expedition to the Black Sea to hunt for shipwrecks as old as 1000 B.C. I met with Dr. Ballard in his office at the Mystic Aquarium’s Institute for Exploration recently, and asked him why, when there’s so much ocean to explore, he keeps returning to the waters off of Turkey’s northern coast.

Dr. Robert Ballard (Photo: Kip R. Evans) Dr. Robert Ballard (Photo: Kip R. Evans) |

BALLARD: Well, it’s because the Black Sea, due to its unique chemistry, has the best-preserved ancient ships in the world. And we want to find them and explore them, because there, we feel, because of their high state of preservation, we can learn more about our ancient history than we could any other way.

ROSS: The Black Sea is where the mythical figure, Jason, traveled in search of the Golden Fleece. And you have actually theorized that, you know, myth and legend are, in a way, perhaps like rumors, probably based in some truth.

BALLARD: Yes, I do believe that most of these legends that were carried on through oral histories, that could last that long, must be such a powerful story that it probably is in some way based upon fact. We do know that the Greeks came into the Black Sea. In fact, we just found a Greek ship from the Hellenic Period in the bottom of the Black Sea, well preserved. So we know the Greeks came in there, and the came in there for food, because the upper layers of the Black Sea, although the bottom layers are dead, the upper layers are very rich and full of fish. And much more so than around the Greek states in the Aegean. And so the Greeks went in there for fish, but they also went in there for gold.

ROSS: Speaking of fish, in your last Black Sea expedition you found things like mollusk shells dating back to 5000 B.C., now extinct. And I’m wondering, is extinction, to you, part of a natural cycle? Or is it, as many of us seem to see it, the result of something negative, something toxic, something necrotic?

BALLARD: We have seen dramatic changes occurring to the Earth through natural forces, some very violent. And that’s just the way it is. We can’t do much about that. But we can do things about ourselves, and so I think the focus is, well, there are things that are being done that are harmful that we can not have happen, and then there are things that we can just explain – happen.

ROSS: Well, along those lines then, I’m wondering, as an undersea archaeologist and explorer, have you seen considerable degradation? Or are you seeing that things are maybe okay?

BALLARD: Well, I know the Phoenician ships we found were covered in trash, lot’s of garbage bags. Did they do any damage? No, not really. There wasn’t any damage being done to them, but it’s sort of sad to see an ancient ship covered in trash. But I certainly have not seen major degradation of deep water sites. But sometimes what you see isn’t what’s there. I know that, for example, certain pelagic animals – out in the middle of nowhere we’ve seen a sudden drop in the lead content of the bodies when we stopped using leaded gasoline. And so the lead had been being carried by the atmosphere - something you can’t even see - and yet it was reaching creatures at great depths and changing their chemistry, probably in an adverse way.

ROSS: How does that all influence the future of all of us who are sitting on this water-filled globe?

BALLARD: Well, first place, you quickly realize that the oceans are the driver of our climate. You may live in Kansas and not think the ocean’s very important, but you better get down on your hands and knees and thank it for the rain. You better thank it for it’s moderating capability. The ocean moderates the climate on our planet. Look at its sister planets of Mars, Venus, and Mercury that are alternating between a burning inferno when the sun hits it and a freezing refrigerator when it doesn’t. So the ocean has a huge impact upon the climate of our planet. It’s also where life began, and there’s more living tissue in the oceans of the world than there are on land. And there’s many unexplored regions of the planet. We haven’t even conducted Lewis and Clark expeditions, or Lois and Clark expeditions, in the Southern Hemisphere of our planet. It’s largely unexplored. We have better maps of Mars and Venus than of Earth. And I think Earth – although I love exploration of outer space – I think the exploration of our own planet is as important or more so.

[MUSIC: Beastie Boys “Song for Junior” Hello NastyCapitol (1998)]

Related links:

- Robert Ballard’s 2003 Black Sea Exploration

- Robert Ballard’s 1999-2000 Black Sea Exploration Back to top

ROSS: Dr. Robert Ballard is off to spend the next 41 days deep in the Black Sea searching for ancient shipwrecks.

Peter Rabbit celebrates his hundredth birthday this year. It was a century ago that English author Beatrix Potter wrote and illustrated the now-familiar story of the mischievous bunny who trespassed in Mister MacGregor’s garden. While Potter went on to fame and fortune as a children’s book writer, her true passion was preserving the landscape that provided inspiration for her stories – the hills and farms of western England’s Lake District. Tom Verde visited the region in search of Peter Rabbit’s creator and has this story.

VERDE: The pastoral charm and rugged beauty of England’s Lake District have inspired many poets and writers . . . Wordsworth, Coleridge, Ruskin, to name a few. But perhaps none has made the region more familiar to us than Beatrix Potter.

POTTER VOICEOVER: The sunshine crept down the slopes into the peaceful green valleys, where little white cottages nestled in gardens and orchards. “That’s Westmoreland,” said Pig-wig. She dropped Pigling’s hand and commenced to dance.

| |

Beatrix Potter with pet Belgian (Photo: National Trust)

VERDE: Potter’s richly illustrated children’s stories such as “The Tale of Pigling Bland,” “Squirrel Nutkin,” and, of course, “Peter Rabbit” established a popular vision of the English countryside that endures to this day. Beatrix Potter with pet Belgian (Photo: National Trust)

VERDE: Potter’s richly illustrated children’s stories such as “The Tale of Pigling Bland,” “Squirrel Nutkin,” and, of course, “Peter Rabbit” established a popular vision of the English countryside that endures to this day.

[BARNYARD SOUNDS, SHEEPS AND COWS]

LEAR: It’s given the Lake District world renowned. People know from reading those books what the Lake District looks like.

VERDE: Linda Lear, a professor of Environmental History at George Washington University, is researching a biography of Potter that focuses on her life as a naturalist. It’s a life that began in Victorian-era London, where Potter lived a privileged but reclusive childhood. Her happiest memories were of family vacations spent in the wilds of Scotland or the Lake District. It’s there, says Lear, she felt liberated.

LEAR: In the country, she was able to wander at will, and to discover at will, and to be away from her family. Nature was the key to her independence, and it starts very, very early, it starts at age five or six.

POTTER VOICEOVER: My dear Papa. Things are not nearly so far on here as I expected. I don’t think the bushes are so green as those in the park in London. We hardly found any primroses, as they are only just coming up.

LEAR: And she’s a compulsive artist, she draws everything in nature she can see, and she gets better and better and better, so she becomes a really fabulous natural history illustrator.

VERDE: As a young woman, Potter considered a career as a botanist, but academia’s all-male bureaucracy stood in her way. She couldn’t even attend the presentation – before a prestigious London botanical society – of her own groundbreaking research on lichen spores because the society didn’t allow women at its meetings.

[BIRD CALLS]

VERDE: Still, there were those who understood and supported her interest in nature. One influential mentor was the Reverend Hardwicke Rawnsley, a co-founder of the National Trust, today one of England’s largest land and historic building preservation organizations. It was Rawnsley who encouraged Potter to submit her first manuscript: a manuscript based on an illustrated letter she once composed for a sick child.

POTTER VOICEOVER: My dear Noel. I don’t know what to write to you, so I shall tell you a story about four little rabbits whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter. They lived with their mother…

VERDE: Much to the author’s surprise, “Peter Rabbit” was a runaway best-seller, and Potter dutifully delivered 22 more titles, at the rate of about one or two a year. Most were set in her beloved Lake District, with its whitewashed farmhouses, rambling gardens, and soaring hills, or fells as they’re called locally.

[TRAIN WHISTLE]

VERDE: Yet, by the early twentieth century, it was a landscape under threat. The railroad brought unprecedented numbers of vacationers to the region, as well as land-hungry developers eager to build houses and hotels to accommodate them. Meanwhile, farming was in decline, the victim of a nationwide recession. Plus, there was a rising demand for factory-made as opposed to locally produced goods. Potter took it upon herself to tackle these threats head-on.

DENYER: What Beatrix Potter did, was to raise money from her little books, quite large sums of money, which she then invested in the landscape.

VERDE: Potter biographer, Susan Denyer.

DENYER: And one of her first farms, Troutbeck Park Farm in Troutbeck, she bought to stop that whole area being developed. It’s very difficult now to imagine that might all be covered in houses.

[BIRD CHIRPS]

VERDE: Potter was purchasing more than just real estate. She was preserving a way of life that had existed in the Lake District for generations. And, she meant to keep it that way. Potter also had strong opinions on livestock, and preferred one local breed of sheep in particular.

BURKETT: In them days, there nearly only was ‘erdwicks in the Lake District.

VERDE: Sixty-eight year old Johnny Burkett is one of a long line of tenet farmers to raise Herdwick sheep at High Yewdale, a former Potter farm, now in the care of the National Trust. Herdwicks are indigenous to the Lake District. They’re able survive on the high, stormy fells where no other sheep can, says Burkett, by virtue of their hardiness and thick, distinctively grey wool. The breed is also unique in that it’s hefted to the land, meaning Herdwicks instinctively stay put wherever they’re born and don’t wander off like other sheep.

[SHEEP BAHS]

BURKETT: Bah, bah. You’re all right, have a look around…

VERDE: In Potter’s day, the breed was in danger of extinction. Disease was one factor. Another was the invention of linoleum, which home owners increasingly preferred over woolen rugs, once commonly made from Herdwick fleece. Potter’s willingness to experiment with costly new veterinary medicines coupled with her sheer determination eventually saved the Herdwick, even though she sometimes rubbed fellow sheep farmers the wrong way.

BURKETT: Me father used to say, when you were buying rams, she was a bit of a nuisance, ‘cause she had bigger pocket than what the ordinary farmer had, and she could get the best.

VERDE: Sheep farming has never been an especially easy, let alone profitable business, and Potter knew it – which is why she encouraged farmers to take advantage of the inevitable tourist trade by operating tea rooms and bed and breakfasts on their farms.

[CONVERSATION SOUNDS IN A TEA ROOM]

VERDE: In the tea room of Yew Tree Farm, owner Hazel Relph sells everything from Herdwick wool sweaters to ground Herdie burgers. The income from wool alone, she says, no longer pays the rent.

RELPH: Fifty years ago there would be four women and four shepherds running this place, and now there’s my husband and I, and I get part time help. But without the bed and breakfast and the tea room and selling our own meat, you couldn’t make a living.

VERDE: Peter Rabbit’s creator wasn’t above a little merchandising herself. Long before there was a Harry Potter, Beatrix Potter patented a Peter Rabbit doll, board game, china set, figurine, coloring book, calendar, even wallpaper and slippers. Yet, she continued to siphon the profits from these products and her books right back into the Lake District. When she died in 1943 at age 77, she left nearly all of her land – more than 4000 acres – to the National Trust for the public’s enjoyment. It remains the largest donation ever made to the Trust and one that helped the then-fledgling organization establish itself.

Today, Potter’s stone farmhouse at Hill Top in the little village of Near Sawrey, the setting for many of her books, is the Trust’s most popular attraction. Visitors from around the world come here to see the real-life home of Peter Rabbit and other familiar characters.

[DUCKS]

VERDE: The challenges of preserving this environment remain much the same as those of Potter’s day. Of the 20 working farms she left to the National Trust, a third have gone under. Meanwhile, the pressures of tourism – even supposedly low-impact eco-tourism – continue to take their toll. Millions of hiking boots tramping across the footpaths have caused erosion in some areas. The Trust’s regional manager, Charles Flannigan, admits there’s much left to be done and that Potter would probably be the first to agree with him.

FLANNIGAN: I think if Beatrix Potter was still alive today, she would say we haven’t lived up to her standards, but her standards were exceedingly high, to an intense degree of detail. Equally, I think times have moved on and we are fulfilling the spirit of her wishes as far we are able to do so.

VERDE: And if Potter was alive today, it’s likely she’d still recognize many of the farms and fells and footpaths she wandered half a century ago. Author Judy Taylor chairs the Beatrix Potter Society.

TAYLOR: Oh yes, I mean it’s been kept exactly as she wanted it. And what it means for us today is that we’re free to roam the Lake District and cannot build on it and it’s preserved for all of us. It’s strange, really, that the royalties from books like the “Tale of Peter Rabbit” and the other little books enabled her to do this for us. It’s lovely.

[SCHOOL CHILDEN AND TEACHER]

VERDE: For Living on Earth, I’m Tom Verde in England’s Lake District.

[MUSIC: Radiohead “There there” Hail to the Thief Capitol 2003]

Related links:

- See a slideshow of Beatrix Potter’s work

- See a slideshow of photos from the area that inspired Beatrix Potter’s work Back to top

ROSS: And for this week - that's Living on Earth. Next week – a new breed of organic, fast food joints are springing up to meet the nation’s growing demand to be fat-free and healthy - and they just may change an industry.

MALE VOICE: I think that there’s no question that we’re going to spawn a whole generation here of these restaurants. But as companies like O’Naturals grow, we will force the MacDonalds, the Burger Kings, the Wendys to come to us. And frankly, they’re here. You’ll see them walking through and taking pictures, and we welcome them.

ROSS: Fast foods’ future - next time, on the next Living on Earth. And remember that between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org.

[SHEEP, BIRD, MEADOW SOUNDS]

ROSS: Before we go, one last stop in the U.K. countryside. Richard Margoschis captured this warm July afternoon on a high open moorland in Wales for the CD “Wild Britain.”

[EarthEar: Richard Margoschis “Welsh Uplands” Wild Britain: Summer to Winter The British Library Board 1997]

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at livingonearth.org. Our staff includes: Jennifer Chu, Andy Farnsworth, Tom Simon, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Nathan Marcy and Liz Lempert. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. Our interns are Carolyn Johnson, Julia Keller, Taylor Ferguson and Mary Beth Conway.

Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Al Avery. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor, Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor, Chris Ballman is the senior producer and Steve Curwood is the executive producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Pippin Ross. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science, and Stonyfield Farm—organic yogurt, cultured soy, and smoothies. Ten percent of their profits are donated to support environmental causes and family farms. Learn more at stoneyfield.com. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Annenberg Foundation, and Tom’s of Maine, maker of natural care products and creator of the River’s Awareness program to preserve the nation’s waterways. Information at participating stores or at tomsofmaine.com.

ANNOUNCER2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea. Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment. The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs. Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

| | | | | | | | |

Missouri River water levels are at the center of a controversy where opposing court rulings may force the Army Corps of Engineers to change the way it manages the river. (Photo: American Rivers)

Missouri River water levels are at the center of a controversy where opposing court rulings may force the Army Corps of Engineers to change the way it manages the river. (Photo: American Rivers)

Barge on the Missouri River (Photo: American Rivers)

Barge on the Missouri River (Photo: American Rivers)  Alabama Attorney General Bill Pryor

Alabama Attorney General Bill Pryor  A participant at Viking Fest in Poulsbo, Washington (Photo: Alf Erickson)

Sound suspicious? It should. Lye is a caustic compound found in soap, oven cleaner and Drano. Dried cod is soaked in it for up to two weeks before it’s boiled down and served as a Jello-like entree. Sound gross? You betcha. Don’t-cha know. Especially the lutefisk’s overpowering odor – a putrescence that is part decomposing fish, part harsh chemical stench. As one popular Scandinavian “carol” goes:

A participant at Viking Fest in Poulsbo, Washington (Photo: Alf Erickson)

Sound suspicious? It should. Lye is a caustic compound found in soap, oven cleaner and Drano. Dried cod is soaked in it for up to two weeks before it’s boiled down and served as a Jello-like entree. Sound gross? You betcha. Don’t-cha know. Especially the lutefisk’s overpowering odor – a putrescence that is part decomposing fish, part harsh chemical stench. As one popular Scandinavian “carol” goes:

Until a century ago, these animals were a common sight on Martinique’s sprawling coconut plantations. The rats were strong swimmers – a talent which might have helped them survive the wrath of plantation workers, who did their best to exterminate them. They hated the rice rat for its relentless destruction of their crops.

Until a century ago, these animals were a common sight on Martinique’s sprawling coconut plantations. The rats were strong swimmers – a talent which might have helped them survive the wrath of plantation workers, who did their best to exterminate them. They hated the rice rat for its relentless destruction of their crops.

Dr. Robert Ballard (Photo: Kip R. Evans)

Dr. Robert Ballard (Photo: Kip R. Evans)  Beatrix Potter with pet Belgian (Photo: National Trust)

VERDE: Potter’s richly illustrated children’s stories such as “The Tale of Pigling Bland,” “Squirrel Nutkin,” and, of course, “Peter Rabbit” established a popular vision of the English countryside that endures to this day.

Beatrix Potter with pet Belgian (Photo: National Trust)

VERDE: Potter’s richly illustrated children’s stories such as “The Tale of Pigling Bland,” “Squirrel Nutkin,” and, of course, “Peter Rabbit” established a popular vision of the English countryside that endures to this day.