March 4, 2005

Air Date: March 4, 2005

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Reining in Mercury

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

As the U.S. nears its first regulations to control mercury from power plants, critics are questioning whether the rule will do enough to protect children from the pollutant. A new study says mercury pollution lowers IQ for hundreds of thousands of children and costs the U.S. economy billions each year. Living on Earth's Jeff Young reports from Washington. (06:00)

Killing Endangered Species To Save Them

View the page for this story

Killing animals to preserve a species? That's the premise of a program designed to sell a limited number of permits to hunters in order to help communities conserve indigenous populations of endangered sheep. Author Daniel Duane went on his first hunt and wrote about it for Mother Jones magazine. He tells host Steve Curwood that after his experience he had to re-think his notions about hunting. (10:40)

An Ice Age Averted?

View the page for this story

Modern advances like autos and power plants have mostly been to blame for causing climate change. But a University of Virginia professor claims our ancestors had a hand in warming the planet. Host Steve Curwood talks with William Ruddiman, who says that human activity 8,000 years ago may have put off an Ice Age. (06:30)

On A Train Heading South

/ Todd SpencerView the page for this story

Global warming is not a likely topic for a modern dance troupe. But ODC Dance of San Francisco decided to tackle the issue with a modern day telling of Cassandra's story, complete with large blocks of ice melting around the dancers. Todd Spencer attended a rehearsal. (05:30)

Emerging Science Note/Garbage Fuel

View the page for this story

Living on Earth's Jennifer Chu reports on a cost-saving process that makes energy from landfill waste. (01:20)

Saving the Bay

/ Andrea KissackView the page for this story

There was a time when the San Francisco Bay was replete with native oysters. But it's been many years now since they were contaminated and fished out. As part of efforts to restore the Bay, Andrea Kissack of KQED reports scientists are trying to bring back these useful and sought-after mollusks. (06:00)

Desert Walls

View the page for this story

For twelve years, Ken Lamberton wrote about the natural history of his desert home in Arizona. His essays described the caves, canyons and dry ponds of the landscape, but it wasn't outdoors where he honed his prose, it was in prison. At 27, Lamberton was convicted of child molestation and sent to jail. He's since completed his sentence, along with a book about the nature of his crime, called "Beyond Desert Walls: Essays from Prison." (10:20)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Daniel Duane, William Ruddiman, Ken Lamberton

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Todd Spencer, Andrea Kissack

NOTE: Jennifer Chu

(THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER)

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

(THEME)

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. With the federal government poised to set new regulations on mercury emissions, there's new evidence that mercury pollution is not only making people sick and lowering I.Q's--it's hurting them in their pocketbooks as well.

TRASANDE: This cognitive impact resulting from mercury pollution has a significant impact on the economic productivity of our nation, which is at least 2.2 and possibly as high as 43.8 billion dollars each year.

CURWOOD: Also, a sexual offender seeks redemption in prison through the study of nature.

LAMBERTON: The damage that it did to my victim, to my family, to my children--it's baggage I'll carry for the rest of my life, that I'll never escape. And y'know, truthfully, I'll probably define myself as a prisoner for the rest of my life.

CURWOOD: Those stories and a dance for a warming planet--this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

[THEME MUSIC]

Reining in Mercury

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Mad as a hatter. Years ago mercury was used to stiffen fur in hat making, but it also got into the nervous systems of hatters and made many of them act crazy. Now in the face of evidence that even small amounts of the metal are harmful, the Bush administration is getting close to regulating mercury emissions from power plants. Trace amounts in coal go from smokestacks into the air, into water and into the human food chain, often through fish. Developing babies are especially vulnerable. A rule proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency would gradually reduce mercury pollution over the coming ten to 15 years. A bill pending in Congress, called Clear Skies, would largely do the same.

But, critics say both measures come up short when it comes to adequately protecting the health of children. Living on Earth's Jeff Young reports.

YOUNG: Researchers at the Mount Sinai Center for Children's Health and the Environment in New York City wanted to know more about what life will be like for children born to mothers who've accumulated mercury in their bodies. Their study, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, found mercury impairs cognitive ability in 300 to 600,000 American children born each year. Study co-author and pediatrician Leonardo Trasande says high mercury means lower IQ.

TRASANDE: These are children for whom their native intelligence is knocked down a bit and they're less sharp in school. The really smart are slightly duller and don't perform well in school.

YOUNG: Trasande's work is the first peer-reviewed medical study to measure the extent of IQ loss due to mercury. His study also looked beyond learning to earning, putting a price tag on the lost job opportunities that result from that lowered IQ.

TRASANDE: This cognitive impact resulting from mercury pollution has a significant impact on the economic productivity of our nation, which is at least 2.2 and possibly as high as 43.8 billion dollars each year.

YOUNG: The broad range comes from the many variables Trasande had to consider. His best guess is a mercury-induced loss of 8.7 billion dollars to the U.S. economy each year. Scientists employed by the electric industry disagree. Michael Miller is environment director for the Electric Power Research Institute.

MILLER: Well, heh, we've got some major reservations about that study.

YOUNG: Miller questions the link between mercury exposure and IQ loss and says the study overstates the role of power plant emissions of mercury. He says most mercury in the U.S. comes from natural sources like forest fires or blows in from industry elsewhere around the world. Trasande stands by the Mount Sinai study and it's caught the attention of a committee advising the Environmental Protection Agency on children's health issues. Committee member John Balbus is health director for the advocacy group Environmental Defense. Balbus says the Mount Sinai study addresses the very questions the committee had been asking EPA.

BALBUS: It raises the question why it took an academic outside the agency to do it when we've been asking the agency to do this kind of thing for over a year.

YOUNG: Balbus says the advisory committee has long questioned the EPA's mercury proposal. Instead of forcing power plants to install the best technology to control mercury, the EPA proposal calls for a cap and trade approach. It would reduce overall mercury emissions by about 30 percent by the year 2012, then 70 percent six years later. Power companies could buy and sell mercury emissions credits to meet those targets. Balbus says the advisory committee sent four letters to EPA questioning whether the proposed rule would make mercury cuts fast enough or deep enough.

BALBUS: And so we asked to see proof that the rule that was being proposed was taking all these factors into account and was coming up with a solution that was best for children's health. That's the kind of analysis we were looking for and unfortunately, I don't think that's the kind of analysis that we ever got.

YOUNG: Some career scientists within EPA raised similar questions about the mercury rule, how it was put together and what it would achieve. Milt Clark is an EPA health and science advisor. He says he can't speak for the agency, but as a scientist, Clark says he does not see how the EPA's proposal will get mercury out of rivers, lakes, fish and people.

CLARK: And the 30 percent has to really be compared with the fact that there would be a potential of several, well, we want to be very clear here, over a million children that would be born above acceptable levels.

YOUNG: A report last month by the EPA's own inspector general echoed those complaints. The report said the agency ignored scientific evidence to set modest mercury limits that would agree with the Bush administration's cap and trade approach in its Clear Skies legislation. Instead of conducting since to determine a mercury limit, the IG report says, the agency worked backwards to justify a predetermined goal. EPA officials declined to grant an interview for this story. In a written response to the Inspector General report, an official called it flawed and inaccurate and said the inspector general had—quote "characterized the process as incomplete before the process has even finished" –end quote. Before the agency completes the mercury rule, Mount Sinai's Dr. Trasande says he hopes EPA will think about the public health costs his study points out.

TRASANDE: It's also unconscionable not to go after the primary problem, which is mercury pollution from manmade sources such as power plants.

YOUNG: EPA faces a March 15 deadline to make its mercury rule final. A committee vote on the Clear Skies legislation is set for March 9th. For Living on Earth, I'm Jeff Young in Washington.

[MUSIC: "The Pearly Eyed March" Birdsongs of the Mesozoic: Dancing on A'A (Cuneiform) 1995]

Related link:

Mount Sinai Center for Children's Health and the Environment

Killing Endangered Species To Save Them

CURWOOD: Thirty years ago, it seemed that the magnificent bighorn sheep of the western mountains were headed for extinction. The bighorn is the most prized trophy of the four North American wild sheep species that hunters consider a grand slam. So, the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep came up with a program to save the endangered animals by killing just a few of them. Saving an endangered species by hunting them sounds like an oxymoron but the organization had the notion that by getting a lot of money for a few hunting permits, they could raise money for sheep conservation and community development. The concept seemed unusual to writer Daniel Duane. So, he joined a foundation hunt in Vizcaino Biosphere, in the south of Baja, California, recently and wrote about that experience in the March issue of Mother Jones magazine. Dan Duane, welcome to Living on Earth.

DUANE: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now as I understand it, before you started doing the research for this story, you had never been out hunting. So, what were your views on hunting up until then?

DUANE: Well, I didn't have very well formed views. I grew up as an urban, liberal environmentalist, with most of my, well, all of my exposure to the outdoors being backpacking in California Sierra Nevada and that sort of thing, and the picture of a hunter, in my mind, wasn't an especially favorable one. And I think if I had any view of them at all, it came from fairly cliched-notions picked up through TV and here and there. And, I don't know, visions of beer-swilling guys driving around in pickups trying to blow away Bambi on the weekends and somehow feeling bigger about themselves when they managed to do it.

CURWOOD: So, that's a pretty negative view in other words.

DUANE: That's a pretty negative view. Yeah.

|

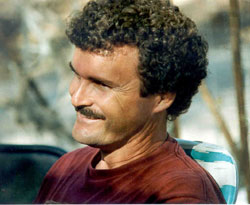

Hunter Brian Drettmann paid $59,000 for the right to hunt this bighorn ram. |

CURWOOD: So, for this story, you end up going out on a trip with a man named Brian Drettmann. He's a wealthy man who's a seasoned hunter from Michigan and as I understand it, he's paid $59,000 at an auction for a permit for, basically, for the right to hunt bighorn sheep which are considered endangered. But, how does this work?

DUANE: So, the way this works is that a wildlife conservation group formed by hunters called the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep got this idea that the best way to raise money for the conservation of wild sheep was to talk to states that have sheep populations into granting the foundation a small number of hunting permits. The foundation then auctions off those permits to the highest bidder and gives 90 percent of the money right back to the state with all of it earmarked for sheep conservation. CURWOOD: Let me see if I figure this out. They kill endangered sheep to save them? DUANE: Isn't that peculiar? CURWOOD: Indeed. DUANE: And, but that's exactly what they do. And they've been very successful at it. The killing of the endangered Bighorn sheep over the last 15 years through these FNAW permit programs has raised many, many millions of dollars for the conservation of those sheep and has been directly responsible for, I believe, it's a four-fold increase in the number of wild sheep in North America. CURWOOD: So, what are the incentives here? How does it work to kill an endangered sheep to save the population? DUANE: The way it works in Baja is that there is a very small and, until recently, dwindling population of Bighorn sheep in a desert mountain range. That mountain range lies within the collective property holding of a group of local rural people. In other words, the Mexican government has granted collective ownership of a large piece of desert to 142 Mexican families. The Foundation for North American Wild Sheep comes down to them and says ‘hey, let's get the Mexican government to grant us a permit to hunt one or two of those bighorn that are on your land.' We'll take that permit up to the United States, we'll auction it to the highest bidder and we'll give all that money right to this Ajito, to this group of families that own this property collectively. And, with that money we will create a conservation program to preserve the Bighorn sheep and that conservation program will employ you guys.' So, a bunch of guys get jobs and an economic incentive is created for all of these rural people to preserve both the bighorn sheep and the habitat on which they live. CURWOOD: So, tell me about the hunt itself. What happened? You get up in the morning, and? DUANE: Well, we get up before dawn. We load up our packs, you know, have breakfast around a fire, load up our packs and start up the mountain. The guides took us up sort of winding, snaking, very steep footpaths. At times we were scrambling on hands and feet. We gained a couple thousand feet elevation to get to a ridge near the summit of the mountain that would allow us to look down into the canyon where the sheep were, moving as quietly as possible and whispering and being careful not to drop anything or brush any sticks. We crept up to the edge there and looked over and down at the sheep. It took a while for Ramon the chief guide to figure out exactly which ram he wanted Brian to shoot. CURWOOD: What was he looking for? DUANE: He was looking for the oldest ram and the ram with the largest rack of horns. CURWOOD: And, why is that good? DUANE: That's good for hunters because hunters like big racks of horns. And, it's good for conservation because the oldest ram in the group has presumably had plenty of opportunity to spread his genetic diversity through the herd. So, Ramon eventually pointed to a particular ram down near a Yucca tree. There was a lot of anxious whispering back and forth between Brian and Ramon to make sure that Brian knew exactly which ram Ramon had in mind. Once Brian was confident, he chambered a bullet in his rifle and settled his crosshairs on that ram and waited for the all clear. For a moment there was a ewe, a female bighorn, standing directly behind the ram. So, there was some concern that the bullet could go through the ram and kill the ewe as well. CURWOOD: What would happen if you killed the wrong ram or the ewe? DUANE: It would have put a real smear on the hunt. It would have been very upsetting for everybody involved. The Ajiditarios are very committed to preserving their sheep. They place an enormous value on preserving their herd and a killed female is a small catastrophe for them. What happens next is that finally that ewe moves, Ramon, the guide, hisses "listo," all clear, and, there's a dead silence in the group for a beat and then this tremendous concussion as Brian pulls the trigger and the rifle bucks. The sheep had all sort of bolted; they had no idea what had happened but, of course, they had heard this terrifying noise. And, then came this groan sort of as Ramon communicated that Brian had missed. CURWOOD: We're speaking with Daniel Duane about hunting endangered sheep in a bid to conserve them. We'll join him back on the Bighorn trail in just a minute. Keep listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: "Rogaciano" La Calaca: Putomayo Presents Mexico (Putomayo) 2001] CURWOOD: We're back with Dan Duane who's telling us the story of his first hunt, a hunt that's sponsored by the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, part of a program that allows hunting of the endangered sheep in order to conserve them. Our story continues as hunter Brian Drettmann, who was paid almost $60,000 for a permit to bag a bighorn sheep, has taken a shot and missed.

High atop Mexico's Tres Virgines volcano, hunter Brian Drettmann takes aim at a bighorn ram as guides uses binoculars and range finders to tell him which animal to shoot. (Photo: Daniel Duane) CURWOOD: And how did you feel? DUANE: I was surprised to feel exhilarated by it. I had wondered what I would feel in that moment. I had really wondered in advance what I would feel watching a man shoot a bighorn ram. Growing up in California and spending time in the mountains of California, the bighorn had always loomed for me as the real sort of mystical inhabitants of the airy keeps of the high mountains. And, I wondered if I was going to feel revolted or saddened or something like that and I didn't at all. I felt exhilarated by it. I felt excited by the adventure of it. I felt privileged to be along with these local men and watching them apply their woodcraft, their tracking and all of that. Another thought I had was, you know, please let me go this way. This guy was, he was near his expected life span anyway. He was in great health. He was eating from a favorite kind of bush. He was surrounded by all his descendants and family and then the lights went out. CURWOOD: So, how do you think your views on hunting changed after this hunt? DUANE: Ray Lee, the CEO and president of the Foundation for North American Wild Sheep, said to me that, in defending hunting, he said to me that, look this is the way people did it for tens of thousands of years. This is how people got food and now we all get our food wrapped in cellophane at the supermarket. And, if you ask a hunter what he's doing out there, he'll tell you: "Look, 362 days a year I get my food wrapped in cellophane and three days, on these three days a year when I go hunting, what I'm doing is putting myself back in, putting myself back in the natural world." And, as someone whose idea of being put back in the natural world has typically meant finding a gorgeous high mountain lake and watching the sunset, it was hard for me to accept the blood sport version of being put back in the natural world until I was out on the mountain with that sheep, watching it being butchered and then eating it. I felt privileged to be there and I did feel that at least in the one setting in which I participated, hunting could really be an extraordinary way to participate in the rhythms of life. CURWOOD: How do you feel about going hunting again yourself? DUANE: Well, I'm curious about it, you know. I was so enthusiastic about this that Brian has invited me to go turkey hunting with him in Michigan this spring and I'm really looking forward to it. I'm curious about it, you know, I mean, again I'm not sure what it's going to feel like because I'll be taking yet another step to actually pull the trigger. But, I plan to have a big dinner party afterwards and, you know, have roast wild turkey for a bunch of friends and learn some good recipes for stuffing, I guess. CURWOOD: Daniel Duane is the author of the article, "Sacrificial Ram," in the March/April issue of Mother Jones magazine. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today. DUANE: Thanks for having me. CURWOOD: And, if you have an opinion about hunting in the name of conservation, we'd like to hear from you. Our telephone number is 1-800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988. Or write to us at comments at loe dot o-r-g; that's comments at loe dot org [MUSIC: Kronos Quartet "Half-Wolf Dances Mad in Moonlight" Winter Was Hard (Elektra/Nonesuch) 1988] Related links:

An Ice Age Averted?CURWOOD: When most of us think about how people might be disrupting the global climate, we tend to blame greenhouse gas emissions from cars, power plants and factories--all products of an industrial society not even 300 years old. But, William Ruddiman, a marine geologist and professor emeritus of environmental sciences at the University of Virginia, has another idea. He thinks our ancestors may have had a hand in climate change, as far back as 8,000 years ago. In a cover story for the March issue of the magazine Scientific American, Professor Ruddiman says early human activity caused atmospheric levels of methane and carbon dioxide to jump at a time when they should have been falling. Up until then, the earth had regularly alternated between ice ages and warming periods, due to the wobbles in our orbit around the sun. And right now, the earth should be on the verge of an ice age. But, since the climate has by and large stayed warm for the past 8,000 years, Professor Ruddiman wanted to know why. He joins me from member station WMRA in Harrisonburg, Virginia. Hello, sir. RUDDIMAN: Hello. CURWOOD: So, what exactly were early humans doing 8,000 years ago that could have brought on global climate change? RUDDIMAN: Well, basically they were farming. They were clearing forests across the southern tier of Eurasia in order to open up land so that the sun could get to the plants. Agriculture had been discovered in a couple of locations in the Middle East and in China 11,000 years ago, but it began to spread into forested areas around 8,000 years ago. So, that's one part of it. The other part is that by 5,000 years ago, people began to flood wetlands in Southeast Asia to irrigate the land to grow rice. So, clearing the forest generates carbon dioxide; irrigating generates methane. CURWOOD: So, your hypothesis is that we would be in an ice age if it weren't for human activity. Do I have that right? RUDDIMAN: That's basically right, although it's easy to overstate it. What I said was that ice sheets of some size would now be growing in the Northern Hemisphere, probably in far northeastern Canada. Now, this should not be understood to mean that there would have been massive ice sheets down to Toronto and Chicago and New York the way there were 20,000 years ago. These would be small, but growing ice sheets. CURWOOD: What did you find in your research that led to your theory of ancient global warming? RUDDIMAN: Well, basically part of my hypothesis is that if greenhouse gases had done what they normally do, what they naturally did in the past for the last three or 400,000 years, they would have decreased during the last several thousand years. But instead they started that kind of decrease but then they turned around and went the other way; they increased, they went the wrong way. Humans were putting greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that warmed up the atmosphere. And, in effect, that warming stopped a natural cooling. It kept the earth from cooling off. CURWOOD: Now, some of your colleagues are skeptical of your hypothesis and the conclusions that you have from the data. We talked to a couple; Professor William Pelletier of the University of Toronto, for example, questions if there really could be, could have been enough deforestation and crop irrigation with the resulting releases of carbon dioxide and methane, to cause the increases that you cite here. How do you respond to this criticism? RUDDIMAN: It is at first blush a valid criticism if you go back say to just before the beginning of the industrial era when I say these greenhouse gas anomalies had reached these very large sizes that I had mentioned earlier. There were about 500 million people, 600 million people around and that's only a tenth of the number of people that are alive today. So, if you look at how much methane or CO2 farming and deforestation generated today, from six billion people, and then you think, oh well, there were only 500 million people alive then, you have to wonder if, indeed, if there is enough farming activity to do that. But, I think there's an underlying fallacy to that point of view and it's basically this: we don't live, the average person today does not live the way the average person lived in 1700 or a 1,000 years ago or 2,000 years ago. Back then, almost everyone was a farmer and so everyone that was farming needed cleared land and therefore deforestation to do the farming. Today, most of us are not farmers and so the relationship is not a one-for-one relationship between population and greenhouse gas emissions. CURWOOD: What are the implications for the future here? If climate change has been an ongoing phenomena for the last 8,000 years from human agricultural activity, what does it mean now that we have all these industrial emissions of greenhouse gases and much larger proportions than our farming ancestors emitted these gases? RUDDIMAN: There is a fundamental difference between the early warming that I claim to have detected and the present day industrial-era warming. The early warming came on very slowly, but it also did not carry the greenhouse gas concentrations or the climate beyond the natural balance that had been varying over the last several 100,000 years. That's not the case for the current warming. The greenhouse gas concentrations are now well outside, well above their natural, the natural range that they have been varying at and the global temperature is just at the point of exceeding the natural range of temperature as well. So, we're heading into terra incognita. We are right now at the warm limit of how warm the earth has been in the last several 100,000 years and we're heading fairly quickly toward something a good deal warmer. CURWOOD: Professor William Ruddiman is author of the article, "Did Humans Stop an Ice Age?" in the March issue of the Scientific American. Thanks for taking this time with me today, Bill. RUDDIMAN: It's good talking to you, Steve.

On A Train Heading SouthCURWOOD: Last year, the disaster film, "The Day After Tomorrow," was a notable attempt by Hollywood to draw wider attention to the issue of climate change. Another effort by the art world to document the warming planet is underway in San Francisco, where one of the city's most respected dance companies is tackling the almost impossibly unglamorous subject. Producer Todd Spencer sat in on a rehearsal of ODC Dance's "On A Train Heading South" and has our story. WAY: Take it slow going back to that place and let her grab you and pull you back to that place. [FLOOR NOISE AND PEOPLE GETTING INTO POSITION, FOOTFALLS] SPENCER: ODC founder Brenda Way has choreographed 70 pieces over the last 30 years, but never one like this. Like me, you might wonder what a dance about, essentially, weather, would look like. You might also question the topic's value as good dance fare, but if the feedback from advance audiences is any indication, the 30-minute dance packs an emotional wallop. [NOISE OF FOOTFALLS] WAY: Did you guys figure out what you're doing there? SPENCER: The piece is the brainchild of Way and composer-collaborator Jack Perla, who pitched the idea to Brenda after a vacation to Antarctica. WAY: He proposed this idea, I thought it was ridiculous. I mean, I thought it was so massive. PERLA: And, I still get that, you know, like, if I describe the piece to colleagues at work…can you really do that? I mean, a dance piece about global warming. It's pretentious. [MUSIC] SPENCER: As it opens, we see the dancers as a picture of society engaged in what could be a fancy, black tie party. An awkward female guest soon arrives. PERLA: Cassandra is, sort of, the party crasher and she's the, you know, she's the downer and she's not a very good conversationalist and she's not very effervescent. SPENCER: In Greek mythology, Cassandra could see into the future. But, stripped of her powers of persuasion by Apollo, she's unable to convince the Greek generals about the danger posed by the Trojan Horse. Throughout this piece, the lone Cassandra figure tries to alarm her fellow dancers about the strange weather. [MUSIC] PERLA: And as the evening wears on, the tension gets greater and greater. It starts innocent; it really becomes quite violent. [MUSIC]

|