August 5, 2005

Air Date: August 5, 2005

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Buyer's Bill

View the page for this story

After years of debate, the energy bill finally passed Congress, and much of what it offers goes to big oil and gas companies, as well as the nuclear industry. But what does it mean to consumers? Host Jeff Young talks with Daniel Friedman, of the Union of Concerned Scientists, about what the average buyer could gain from the nation's new energy policy. (07:30)

Living it Up

View the page for this story

A spread in this month’s Outside magazine reveals what makes a utopia and why we want to live in one. Host Jeff Young talks with Senior Editor Dianna Delling about their top picks in the US, towns that are smart and progressive, beautiful, livable, and fun. And if you can’t move, advice on how to turn your town into the promised land. (04:30)

Grazing up the Land?

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

For the first time in a decade the federal government is revising rules about how ranchers graze their cattle on public land. The changes tend to allow ranchers more leeway and make it harder for range land officials to order cattle off when they perceive cattle-caused damage. But beneath the changes producer Clay Scott reports a deep debate over the wisdom of public grazing persists. (10:00)

Manufacturing Science

View the page for this story

Industry groups often attempt to block efforts to regulate them by attacking the science used to support those efforts. Host Jeff Young traces the history of this practice with public health researcher David Michaels and looks at how it has become entrenched in U.S. law. (06:00)

Emerging Science Note/Bug Spray for the Birds

/ Sarah WilliamsView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Sarah Williams reports a chemical in birds might be the solution to summer's insect pests. (01:20)

Off the Beaten Path

View the page for this story

Scientists are discovering that tiny particles associated with freeway exhaust are unhealthy for people to breathe day after day. Now that science is beginning to lead to changes in ideas about what should and shouldn't be located near freeways. Ky Plaskon reports from Las Vegas. (03:00)

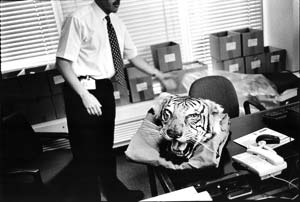

Poaching Pictures

View the page for this story

Patrick Brown tracks the illegal wildlife trade in Asia—with a camera. His black and white photos tell the story of the business of trafficking animals--from the small-time poacher to the tables at the marketplace to international airports and Scotland Yard whose staff of four is charged with curbing wildlife smuggling. Brown tells Living on Earth’s Jeff Young that he hopes to use his work to educate some of the people involved in the business. (06:30)

Seized Menagerie

/ Eric WhitneyView the page for this story

Reporter Eric Whitney takes us to The National Wildlife Products Repository outside Denver, Colorado. Here, more than a million illegal wildlife items—including stuffed tigers, snake boots, and dried seahorses—are catalogued, stored, and donated to schools, museums, zoos, and research facilities. (05:00)

Taking it all Back

View the page for this story

Former skeptics of the recent Ivory-billed woodpecker sighting are reversing their doubts after being presented with new audio evidence that they've deemed unequivocal. Host Jeff Young talks with the recently converted Richard Prum, an ornithology professor at Yale University. (02:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young

GUESTS: David Friedman, Dianna Delling, David Michaels, Patrick Brown, Richard Prum

REPORTERS: Clay Scott, Ky Plaskon, Eric Whitney

NOTE: Sarah Williams

(THEME MUSIC)

YOUNG: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

(THEME MUSIC – UP AND UNDER)

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young. With the President’s signature on a new energy bill, companies stand to gain billions. But what’s in it for energy consumers?

FRIEDMAN: This is the government rewarding consumers for taking the patriotic step of buying higher fuel economy vehicles. At the same time, there’s more than twice as many tax breaks going to an oil industry that’s currently reaping record profits.

YOUNG: A user’s guide to the energy bill. Also, Western ranchers face new realities on the range.

MAN: We have to learn to share with the public. If we don’t, we’re not going to be here. There’s a lot more public than there are us. And I think we can both be on the landscape and both use it.

YOUNG: Those stories, plus, bug spray from bird feathers, and the final word on the ivory-billed. Yes, it’s for real, so don’t knock that woodpecker. This week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from ‘A Beautiful Place Out in the Country’ (Warp Records- 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support from Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

A Buyer's Bill

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studio in Somerville, Massachusetts, it's Living on Earth. I'm Jeff Young, sitting in for Steve Curwood.

YOUNG: Well it took nearly five years of trying, but President George W. Bush now has one of his top legislative desires, an energy bill to sign. The President says it will set the country on a course to meet growing energy demand. Critics call it a big industry give away that will do little to reduce our dependence on oil, or lower gas prices. With nearly 15 billion in tax breaks, there’s no doubt energy companies will benefit, but what about energy consumers? What’s in it for you? David Friedman has gone through the energy bill looking for perks for the consumer. He directs research for the Clean Vehicles Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Mr. Friedman, welcome to Living on Earth.

FRIEDMAN: Hi, thank you very much.

YOUNG: Well, let’s start with cars. What’s in this for average Joe or average Jane who’s out on the car lot looking for a new car?

FRIEDMAN: Well, if you are in the market for a new car, especially a high fuel economy car, Congress has provided tax credits for new hybrid electric vehicles. These credits are going to range from anywhere from $250 all the way up to $3,400 all depending on the fuel economy improvement of that vehicle.

YOUNG: Now a tax credit is better than a tax deduction, right?

FRIEDMAN: A tax credit is much better than a tax deduction. It’s worth what it says at face value so if you qualify for a high fuel economy vehicle that gets a $3000 tax credit, that’s $3000 off the sticker price of the car. This is replacing a tax deduction that’s currently on the books for hybrids. This year that tax deduction is about $2000, but because it’s a deduction it’s only worth about $4 to 600 in your pocket depending on your tax bracket.

YOUNG: Now you know what they say, the large print giveth, the small print taketh away. Is there fine print here we need to be on the lookout for, some kind of a limit on how many of these can be taken advantage of or something along those lines?

FRIEDMAN: Well, that’s absolutely true. There is a limit that Congress did put on the hybrid vehicle tax credits where automakers can only sell about 60,000 of the hybrids per manufacturer before they start phasing out. Sadly what this does is it rewards automakers who are late to the party. Companies like Honda and Toyota and Ford, who are selling tens of thousands of these hybrids already, they’re going to hit the cap within six months to two years. Whereas companies like General Motors and Daimler Chrysler who haven’t even put any real hybrids on the road yet are still going to be getting these credits, well into 2009. That means you could walk into a showroom and get more money back for a GM hybrid that gets lower fuel economy than a great Toyota Prius, for example.

YOUNG: Hmm. Any idea why it was put together that way?

FRIEDMAN: Well, it seems like a mix of a couple of things. Part of it I think is good old honest attempts to protect GM and Daimler Chrysler and to try to give them a little bit of a benefit to compete against what’s happened with Toyota and Honda. On the other side, I think that Congress just decided they didn’t want to spend as much money on this which is really too bad. This is the government rewarding consumers for taking the patriotic step of buying higher fuel economy vehicles. At the same time there is more than twice as many tax breaks going to an oil industry that is currently reaping record profits from your and my pocketbooks.

YOUNG: I’m switching gears slightly, pardon the pun, but if I want to improve the fuel efficiency of my home by let’s say, better, more fuel efficient appliances, what’s in there for me?

FRIEDMAN: Well, if you’re interested in more fuel efficient appliances which you should be even without a tax credit because they’re going to save you money on your electricity and natural gas bill, you can get a credit of $100 to $175 for things like high-efficiency dishwashers, clothes washers, refrigerators, and other items that meet minimum efficiency standards.

YOUNG: And is there incentive for better insulation and things like that?

FRIEDMAN: There are incentives to effectively upgrade your home to create more energy savings when it comes to things like putting in insulation, better windows, more efficient furnaces and hot water heaters. There you can get a ten percent tax credit with a limit of $50 to $300 depending on the item and then an overall cap of $500 on top of that.

YOUNG: Now is that really that big a deal? Because I mean, it seems to me that most newer homes are already pretty well-insulated and you know the construction codes have changed to encourage the stuff all along the line. Was that really that big a step forward?

FRIEDMAN: Well, it’s definitely an important step forward because construction codes have changed over time and that means the older houses that are on the market have too little insulation, windows that let too much heat in and too much heat out and boilers and hot water heaters that just waste a lot of energy, so this is an important signal from the government that you’ve got to upgrade your appliances, you’ve got to upgrade your home, but sadly it’s only a two-year credit.

YOUNG: Now if someone wants to go solar, what’s the incentive there?

FRIEDMAN: Well, there’s an incentive to put on solar hot water heaters or solar panels that can generate electricity on the roof of your house. These are great ways to actually even see your electric meter turning backwards during a nice hot summer as the solar panel generates your own electricity. Here you can get a tax credit of 30 percent off the cost of the solar hot water heater or solar panel up to about $2000. Again, that’s only limited to two years.

YOUNG: Well, these sound, these sound pretty good, what do you see in here that is not good for consumers?

FRIEDMAN: Well, two of the big things that are not good for consumers are the fact that Congress basically ignored two really important opportunities to save consumers tens of billions of dollars every year. The country really is going to see no relief from oil dependence, no relief from high gas prices because Congress decided not to improve the fuel economy of our cars and trucks. If we had just taken conventional technology and required automakers to improve fuel economy from today’s 24 to 40 miles per gallon, consumers could be saving 80 billion dollars a year by 2020 on gas bills.

YOUNG: So stacking this up from the consumer's perspective, how does this bill compare to say past energy policies or other incentives and credits that were already in place?

FRIEDMAN: Well, this energy bill moves the ball forward a little bit for consumers, but we still got a lot farther to go. Even on the electricity side, consumers could have been saving nearly 30 billion dollars a year, that’s over $200 a household in 2020 if it required more renewable electricity, so it’s a small step, but overall the package is a move in the wrong direction. It increases our dependence on oil and increases our reliance on fossil fueled electricity.

YOUNG: David Friedman is research director of the Clean Vehicles Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks very much for talking with us today.

FRIEDMAN: Thanks for having me on.

Living it Up

YOUNG: Now, I’m sure you’ve got a soft spot for the town you call home, but would you call it an urban utopia? Is it hip? Is it smart? Is it packed with adventure? The latest issue of Outside Magazine says such places really do exist. It lists towns, buildings, smart communities, reviving city centers and making outdoors play part of every day life. Outside’s senior editor Dianna Delling helped compile that list. Diana, thanks for talking with me.

DELLING: Thanks for having me.

YOUNG: So you call these towns, “hip, smart, packed with adventure.” I’m wondering, how does one measure hipness? Because I’ve always wanted to know.

DELLING: For us hip meant places where things were happening. Places where there was a buzz about what’s going on, what the citizens are doing, what the governments are doing, everyone’s working together in these towns to make them better places to live and that’s what really attracted us.

YOUNG: Who made the list here? Give us a few towns on the list.

DELLING: Ok, well we’ve got Chicago, Illinois; Portland, Oregon, of course a long-standing Utopian, forward-thinking town. We’ve got Fort Collins, Colorado; Charleston, South Carolina; Davis, California; Salt Lake City, Utah.

YOUNG: What did you learn about what made those towns the way they are? Is it a particular mayor who’s pushing things in a direction or is it a general ethic among the community there?

DELLING: It was both really. In some cases mayors were really leading the way. In Chicago Mayor Daly, in Salt Lake City Mayor Anderson, but it wasn’t, it can start with the mayor, the mayor can push agendas, the mayor can bring up ideas. But I think for cities to really take off and become more livable, it takes involvement by citizens, businesses, government officials, really everybody involved and that’s what we saw in these cities.

YOUNG: Let’s talk about an example, being able to bike to work or bicycle for recreation seem to be a pretty important thing in your measurements here. I’m someone who’s been as a bicyclist on the business end of a car bumper a few times and maybe it’s just the repeated head injuries talking here, but I’m wondering, is there a way to make cars and bikes get along? How have they done it, these towns?

DELLING: A number of ways, not necessarily a safety issue, but a bike safety issue was addressed by the city of Chicago with their Millenium Park bicycle station. The city has an indoor facility so that commuters can store their bikes during the day. They can even take a shower and get bike repairs while they’re at work with this facility and that’s really innovative and really encouraging to get people out of cars and biking to work. A town like Davis, California is very dedicated to having a network of paths that take you almost anywhere in the city. Even new developments in the city of Davis are required to connect this network of bicycle trails.

YOUNG: You know I think there might be a connection here. In Davis, California, you have a local joking that rush-hour is just before seven o’clock in the evening because that’s when everybody’s heading out for these committee meetings of these various do-good organizations, community improvement organizations that they’re involved with. No coincidence I’m guessing, right?

DELLING: No it all seems to be connected. When you get people interested and involved in improving their communities, things start to happen.

YOUNG: You know, the transportation bill, this big highway bill that just passed Congress, I understand 25 million dollars is going to Columbia, Missouri for new bike and pedestrian trails. Do you see a hopeful trend here? Do you see that, goodness, is the federal government getting hip, is that what we’re seeing here?

DELLING: I hope so, I hope it’s a good sign. I know that in the state of New Mexico we’re also in the process of putting in a light rail system that will connect the city of Santa Fe, the city of Albuquerque, and some of the southern communities. I think it’s a great trend and I definitely hope we see more of it.

YOUNG: One of the measures that you include here is how much a house would cost you if you went to move there and of course, that’s also sort of an indirect measure of the economic vitality of an area, and most of these it seems to me are fairly well-to-do. Is that what we’re really talking about here is just well-off places that have a lot of disposable income for recreation?

DELLING: Not deliberately. I agree that many of the median home prices are a little bit on the high side as home prices are throughout the country. I don’t think that a well-to-do community necessarily means that the place will be more livable or more interested in improving its quality of life.

YOUNG: Dianna Delling is senior editor of Outside magazine, and its August issue lists the Utopia towns of the U.S., livable places in the U.S. Dianna, thanks for talking with me.

DELLING: Oh, thank you.

[MUSIC: Turtle Island String Quartet “Crossroads” from ‘TISQ: A Windham Hill Retrospective’ (Windham Hill- 1997)]

YOUNG: Coming up, grazing on public land. New rules to keep those dogies rolling, and more. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Related link:

Outside Magazine, August 2005 issue

[MUSIC: Andrew Bird’s Bowl of Fire “Feetlip” from ‘Oh! The Grandeur’ (Ryko-1999)]

Grazing up the Land?

Land that belongs to the Bureau of Land meets privately owned land in southwest Montana. (Photo: Clay Scott)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. Across the American West, thousands of ranchers graze livestock on public land. The ranchers pay fees to use the land, and many ranch families have been doing so for generations. Now, the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management, the agency in charge of millions of public acres, has new regulations on grazing. The BLM says the new rules will preserve open space while keeping ranchers on the land and rural communities intact. Some scientists and environmentalists fear those new rules will harm rare species and water quality. Some wonder whether livestock belong on public lands at all. Clay Scott reports.

[SOUND OF CATTLE MOOING]

SCOTT: Cattle have grazed the ranges of the West for over 150 years. It’s hard to find a landscape here that hasn’t had cattle on it at one time. Much of this rangeland, over a hundred and sixty million acres of it, is federal land administered by the BLM. These lands are largely sage-steppe, a landscape that for a long time was overlooked and underappreciated. In fact, it was considered unsuitable for anything but grazing. Now it’s increasingly being recognized as both extremely diverse in plant and animal life, and extremely fragile. This growing biological understanding means ranchers and their grazing practices on these lands are coming under greater scrutiny. Nathan Finch is a southwest Montana rancher.

[SOUND OF PICKUP TRUCK ENGINE RUNNING]

The view from Hugo Turek's ranch looks out to Square Butte and the Highwood Mountains. (Photo: Clay Scott)

FINCH: The pictures you see, and the people that say that, you know, public lands are, you know, all grazed down to the dirt. Well, here you go, it’s not! You know? I mean, it’s really not.

SCOTT: Finch takes me on a tour of his ranch, both his private land and his BLM allotments. To my eye, the sage brush and the grasses beneath it look vibrant and healthy. The rolling sage flats rise to meet the Big Hole Divide mountains in the distance. This is crucial habitat for threatened sage grouse, and a tiny creek running through the place holds rare west slope cutthroat trout. Finch says he grazes conservatively, and that he’s careful not to leave his cattle for too long on one pasture. He resists the notion that any outsider might be able to take care of the land better than he is doing.

FINCH: I try, as best I can, to be open-minded, and try to find the things that work for us. And I know that a lot more guys, to be successful in ranching, are having to do the same thing. I don’t think you can just keep doing it the way grandpa did it. And I think there were grazing abuses in the past, and I’m sure there are still some now, and I’m sure some people would say the way I’m doing is a grazing abuse. But, I mean, I’m not going to try to answer to those people.

SCOTT: The real pressure that ranchers face is economic, and with that comes the threat of subdivision. Many ranchers say, and westerners agree, that the phenomenon of subdivision is changing the landscape and culture of the West more rapidly and dramatically than any other factor. Baby boomers by the thousands are buying up ranchettes for second homes or for retirement in every western state. It is partly to address these pressures, and help keep ranchers on the land, that the Bureau of Land Management has eased some restrictions on public land grazing. The BLM would not be interviewed for this story. Instead, spokesman Tom Gorey read this statement.

GOREY: Regarding the grazing regulations that we’re developing, we’re not going to comment on litigation which has been filed. We will say though that we’re in the process of finalizing the new rules. When that job is done, we expect a rule that’s going to be good for the land, good for people. It reflects our commitment as an agency to multiple use management of the public lands, of which grazing is a part. And we think when all is said and done, this is going to ensure the health and productivity of the public lands, both now and in the years to come.

SCOTT: But the BLM’s new grazing regulations have proven to be controversial. Two BLM biologists who voiced concern about the revised rules quit in protest, saying their analysis had been turned on its head, and that the new rules could be harmful to wildlife and water quality. Tom Lustig, an attorney for the National Wildlife Federation in Boulder, Colorado, echoes those concerns.

LUSTIG: Under these regulations, the right of the public to participate in that, and the obligation of the Bureau of Land Management to notify and consult with the public on many critical, on-the-ground decisions, is eliminated.

|

SCOTT: Up till now, BLM experts have had the authority to make on-the-spot assessments of range health, removing cattle if they saw a piece of land or stream was being damaged by grazing. Now they'll be required to collect extensive data. LUSTIG: Under the new regulations the range manager is going to have to set up a monitoring program, and to periodically take data, perhaps over months or years – to back up his determination that, yeah, this stream is completely beat up, and it’s beat up by cows. What the new regulations do by inserting this monitoring requirement, is create a very high hurdle – perhaps insurmountable in some cases – for BLM to actually enforce these performance standards for healthy rangelands. SCOTT: The result, says Lustig, is that management of the BLM rangelands will fall primarily to ranchers. LUSTIG: I don’t dispute that ranchers are often good stewards. What I’m concerned about is that they have a narrow interest, and by law, the Bureau of Land Management is required to manage these federal lands for multiple uses. And those multiple uses may include things that have nothing to do with livestock grazing. SCOTT: While the BLM rules may represent a move toward making life easier for public land ranchers, another trend is running in the opposite direction. For many critics of public land grazing, the harmful impacts of cattle on arid rangeland are beyond dispute. Debra Donahue is a professor of public land law at the University of Wyoming. She’s also the author of ’The Western Range Revisited,’ a book in which she advocates removing livestock from public lands. DONAHUE: We need to keep in mind, I think, that ranching is not going to end if ranching on public lands ends. SCOTT: When cattle are grazed on arid land over a period of time, she says, the impacts on the land and on native biodiversity can be severe and lasting. DONAHUE: You keep stressing the land, you keep disturbing it, and pretty soon you reach what the ecologists will call a threshold. And that’s a point of no return essentially. The conditions, the vegetative and soil conditions in that spot will change irrevocably, or at least irrevocably under natural processes, meaning you can remove the cattle, it will never go back to the way it was or could be or should be. SCOTT: But there is no consensus when it comes to the science of range management. Some specialists say grazing can be beneficial to diversity. Jim Hagenbarth is a fourth generation rancher with BLM allotments in both Montana and Idaho. HAGENBARTH: For a biologist or a hydrologist to go out on a piece of range, and just blindly say that there is a problem, and livestock are the problem, and they have to be removed immediately, is not good range science. There’s a lot of things going on out there, including drought, wildlife, that determines the condition of the range site, and so you don’t make snap decisions out there. [BIRD SOUNDS]  Land that belongs to the Bureau of Land Management meets privately owned land in southwest Montana. (Photo: Clay Scott) |

SCOTT: Hugo Turek is a Montana rancher and former sociology professor whose ranch is a haven for wildlife. His cattle graze on both BLM and private land on the edge of the badlands south of the Missouri River. This is a rich and diverse landscape, with flat grasslands plunging down into steep, sage-covered breaks, a year-round stream lined with cottonwoods and willows, and, in the distance, Square Butte and the Highwood Mountains. There are elk here, deer and antelope, and countless species of birds, plants and small mammals. Turek sees no contradiction between managing the place for wildlife and managing it for cattle. TUREK: I don’t really differentiate between my land and the BLM land – it’s all one landscape. When you look out across this place, you’re looking across a landscape. And by protecting my place, I’m protecting the BLM, and vice versa. And so there’s a mutual benefit, and these boundaries are artificial. They really are. SCOTT: Though critics say public land ranchers could survive without federal lands, Turek says he needs them for his economic survival. With that need comes a deep respect. TUREK: My view of the public lands is, we ranchers have to share it, we have to learn that this is really the public’s land, not mine. I have the privilege of grazing out here, and I have the privilege of looking across this landscape every day. And it’s difficult to look across this and say, you know, ‘this isn’t mine. This belongs to the public.’ And, but once you can say that to yourself, once you can accept that, and realize you’re out here as a privilege and not a right, it makes it a lot easier to deal with. We have to learn to share with the public. If we don’t, we’re not going to be here. There’s a lot more public than there are us. And I think we can both be on that landscape, and both use it. SCOTT: The conflict over the public rangelands of the West is not likely to be resolved any time soon. It is clear, however, that the public’s awareness of these lands is growing, and that, increasingly, the public will demand a say in how they are managed. For Living on Earth, I’m Clay Scott in Montana.

Manufacturing ScienceYOUNG: From grazing out West to global warming, pesticides to painkillers, public policy questions often come down to one group’s science versus another’s. And increasingly those disputes include accusations of junk science. Scientific studies are attacked as invalid or inconclusive, and can leave the public with more doubt than answers. Dr. David Michaels looks into this trend in a recent supplement to the American Journal of Public Health. He argues that much of the squabbling over scientific certainty is the result of a concerted strategy by those who want to avoid government regulation. Dr. Michaels teaches environmental and occupational health at George Washington University. He joins us from the NPR studios in Washington. David Michaels, you title your article “Manufacturing Uncertainty.” What does that mean? MICHAELS: Well, what I’m talking about here is a strategy of essentially creating doubt. The tobacco industry figured this out 50 years ago. By attacking the science behind the relationship between cigarette smoking and say lung cancer, they were able to keep producing their product and selling it and killing people for decades. That strategy has now been widely disseminated and it’s used by polluters and manufacturers of dangerous products who understand that they can slow down regulation and defeat it in many cases by attacking the science. YOUNG: You know, I feel like backing up a little bit to gain a better understanding of why this approach works. And it only works because there is a certain degree of uncertainty in science and why is that, I mean we look to science to answer questions for us, why can’t they remove the doubt? MICHAELS: We’re doing stories on people and on animals, when we do a story on animals we can control the laboratory procedures. We still have to extrapolate that to humans so it’s never a perfect, sort of if it causes something in animals it causes it in people. When we do studies in people, you know we’re thinking about exposures that occur over the course of 20, 30 years or more. Everybody has multiple exposures in their lifetime and so the answers are never precise. And so we have to, scientists and regulators are faced with the question, how do you weigh the evidence, how do you make the best judgment based on the best current available evidence. YOUNG: I guess the comeback to that is, at what cost? At what point is it just so prohibitively costly to eke out these extra measures of public safety? MICHAELS: Absolutely right. That’s one of the things we think about. That’s rarely discussed because a lot of the corporations have realized that once you get to the discussion of how much risk are we willing to allow, they’ve lost the debate. It’s already been acknowledged that their product causes the outcome in question. So instead they focus on the science. In fact, your question is a better one, saying okay there’s a risk here. How much risk will we allow at what cost and that’s a perfectly reasonable discussion to have and it’s reasonable for regulators to say it will cost too much to prevent this problem. YOUNG: Another thing we should probably point out here is industry groups aren’t the only ones playing this game. I mean, environment and public health advocates will also be somewhat guilty of this, won’t they when they want a hundred percent assurance that say, a pesticide is not going to be harmful. MICHAELS: I agree and I think there are actually examples where environmental groups have pushed far too hard and really made that demand. The difference is these groups have far less power than the chemical industry and the White House right now in making decisions and so I think we always have to look at this and we have to look at you know, what are the demands being made. But right now I think the threat to public health comes from the industries and unfortunately from the White House. They’re essentially demanding certainty when they can never have it. YOUNG: So this was an industry strategy by and far, to fend off the federal government attempts to regulate things. But as I understand part of what you’re arguing here is that this has kind of hopped the fence now and has become part of the way the government is doing it’s work. Is that correct? MICHAELS: It’s unfortunate. It mean, it really, we see it really in the last few years. There’s a very telling memo written by Frank Lutz who is the political consultant to the Republican party, who wrote a memo to the Republican party, essentially saying, how do you win the global warming debate? He said, ‘Voters believe that there is no consensus about global warming within the scientific community. Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled their views of global warming will change accordingly. Therefore you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate.’ YOUNG: So is there evidence people in positions of power took Mr. Lutz’s advice? MICHAELS: Well, it just came out a few months ago, there was a very telling revelation that a fellow named Phil Cooney, who was the chief of staff of the White House’s council on environmental equality actually rewrote a report written by the Environmental Protection Agency using exactly the strategy, changed the words around to say there’s a lot more uncertainty than the EPA suggested and essentially neutering the report saying we can’t do anything because there’s so much uncertainty. YOUNG: In addition to the Frank Lutz example, you see this becoming "institutionalized," is the word that you use. How has this strategy worked its way into the way federal government does its business? MICHAELS: Well, it’s done through a number of ways, the most important one probably is there’s some very obscure legislation called the Data Quality Act. A couple of lines snuck into a very large piece of legislation that had nothing to do with it a number of years ago that essentially requires federal agencies to set up a system where anybody who doesn’t like, not just regulation, but anything the government said and it forces the government to spend a lot of resources defending itself and in many cases it really, it’s discouraging agencies from taking on new issues because they know they’re going to end up in court. YOUNG: What do we know about the lineage of that little piece of language there? Where did the Data Quality Act come from anyway? MICHAELS: Well, it turns out some tobacco experts did some research and we have an article in this new supplement of the American Journal of Public Health where they actually find that the tobacco industry was very much behind it. They were very concerned about the EPA’s assessment of environmental tobacco smoke as being a cause of lung cancer among people who didn’t smoke. YOUNG: The whole second-hand smoke thing. MICHAELS: That’s exactly right, so they were the ones who wrote it and they were the ones who pushed it, but they did through some consultants and only through a great deal of research were there fingerprints found and that’s an interesting article. I think people might want to take a look at that. YOUNG: David Michaels is a research professor in environmental and occupational health at George Washington University. He was contributor and editor on a recent supplement of the American Journal of Public Health. It looks at how science is used in public policy debates and a link to the supplement is available on our web site, loe.org. Thanks for being with us today. MICHAELS: Thank you. Related link:

Emerging Science Note/Bug Spray for the BirdsYOUNG: Just ahead: Pictures from an execution. A photographer's work documenting the illegal trade in rare animal parts. First, this note on emerging science from Sarah Williams. WILLIAMS: When marine biologist Hector Douglas arrived on Kiska Island in Alaska to study crested auklets, the first thing he noticed was the birds’ pungent smell. Now, that observation could lead to a potent, new insect repellent. The crested auklets on Kiska Island spend their days on the ocean, feeding on tiny plankton. When the birds return to their nests in the evening, the citrusy odor produced by specialized glands can be detected for miles. Years later, Douglas was studying another population of auklets, on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea. He noticed the smell again, and this time, something else. The mosquitoes, ticks, lice, and other pests that bothered the island’s other birds didn't bother the auklets. Douglas guessed this was related to their tangerine-like scent. To test his hypothesis, he brought auklet feathers back to his lab and analyzed their chemical make-up. He dabbed samples of the isolated chemicals onto filter paper and attached the paper to his hand. Then he put his hand into a cage swarming with a breed of particularly aggressive mosquitoes. The mosquitoes stayed away, even flying to the other side of the cage to avoid the smell. For auklets, the scent could be a survival advantage, cutting down the chance of diseases that insects carry. For us, Douglas' discovery could lead to a new and powerful commercial insect repellent. The next step, says Douglas, is to do some testing to determine if his Auklet spray would be safe for humans. YOUNG: And you’re listening to Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, online at mott dot org, supporting efforts to promote a just, equitable, and sustainable society; the Kresge Foundation, building the capacity of nonprofit organizations through challenge grants since 1924. On the web at kresge.org; the Annenberg Fund for excellence in communications and education; and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, from vision to innovative impact, 75 years of philanthropy. This is NPR, National Public Radio. [MUSIC: The Album Leaf “Streamside” from ‘In A Safe Place’ (Sub Pop - 2004)] Off the Beaten PathYOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Scientists are learning more about just what comes out of the tailpipes of our cars, trucks, and buses and just what it does to us. The more they learn, the more they warn against putting schools next to freeways. Microscopic particles of soot and metal are concentrated near busy roads and they’re linked to a host of health problems including heart disease and asthma. California was the first state to keep new schools at least 500 feet from freeways and the idea appears to be spreading. Ky Plaskon from KNPR in Las Vegas reports. [HIGHWAY SOUNDS ] PLASKON: Highway US 95 in Las Vegas is a typical urban freeway: Overcrowded. When Nevada started to widen it 10 years ago the Sierra Club stood in the way. It sued, saying the state and federal government didn’t properly consider the serious public health impacts of more vehicles. The legal gridlock lasted a decade until last month when the Federal Highway Administration conceded that freeway pollution might have a negative impact on health. Administrator Mary Peters announced a settlement with the Sierra Club. PETERS: We will monitor vehicle emissions at several major highway locations around the country, helping us to better understand the nature of these transportation emissions. PLASKON: As part of the settlement the federal government will monitor 7 harmful pollutants including benzene, acrolein, formaldehyde, diesel exhaust and tiny particles as they float from the freeway to neighborhoods nearby. [SOUND OF CHILDREN PLAYING] PLASKON: At Fyfe Elementary in Las Vegas, children are playing less than 100 feet from U.S. 95. As part of the settlement the school district will get 3 millions to install advanced air filtration systems, make its busses less polluting and move play equipment away from the freeway. Sierra Club Attorney Joanne Spalding negotiated the deal. SPALDING: What they are doing what is new and exciting is that they’re doing actual monitoring to measure the level of pollutants next to the freeway and in the background and at distances in between and then inside the schools they are testing an air filtration system that’s designed to reduce air toxins from highways. PLASKON: The Sierra Club didn't get everything it wanted. It dropped a demand for a mass transit corridor along the freeway. Still, it considers the settlement a new tool against freeway expansions nationwide. It’s using the same health arguments to oppose projects in Utah, Texas, Wisconsin, Illinois, Ohio, and Maryland. BECKER: We are beginning to see a trend. PLASKON: Bill Becker directs the Association of Local Air Pollution Control Officials. BECKER: And it is just a matter of time until those exemplary actions catch on throughout the rest of the country. So I predict that within a couple or three years you’ll see the same kinds of ordinances almost everywhere. PLASKON: One place that’s already examining freeway pollution is Denver. The Department of Transportation there is going beyond federal requirements and instead using public health data collected at schools before approving two freeway expansions. Las Vegas is also considering an ordinance similar to California’s. One that says new schools should be set back from freeways. From Living on Earth, I’m Ky Plaskon in Las Vegas. [MUSIC: Ben Charest “Cabaret Hoover from 'The Triplets of Belleville’ (Higher Octave-2003)] Poaching Pictures

In the Thai/Burmese border towns of Moung La and Tachilek, markets display everything from rhino horns to macaque skulls for tourists. (Photo: © Patrick Brown/Panos) YOUNG: Flip through the current issue of Mother Jones magazine and you’ll come across some startling black and white images of rare Asian animals. You’ll also see images of some of the people making these animals even more rare—poachers and dealers in the illegal trade in wildlife. Photographer Patrick Brown trekked through southern Asia to take those pictures and he’s with us now to talk about them. Mr. Brown, welcome to Living on Earth.  Thai officials seize a live pangolin at Bangkok International Airport. (Photo: © Patrick Brown/Panos) |

BROWN: Thank you very much for having me. YOUNG: You’ve been following the illegal animal trade for almost three years now. What is it about this that holds your interest as a photographer? BROWN: Well, I focused not so much on the animals themselves, but I photographed more on the social implications of this trade and I wanted to try and feel and get the information across to the viewer of what it’s like to be these hunters, be those poachers, actually switch the roles around because these guys don’t really know what they’re doing so I’m trying to show the viewer a story of what’s actually happening on the cold face so to speak. YOUNG: It does have a very documentarian feel to it, like you said these aren’t beauty shots of wild animals. One here that kind of jumps out at me, it’s a stall in what looks like an open-air market and the table there is covered with skulls and different animal parts for sale, where is that photo, and what’s going on there? BROWN: That’s on the northern border of Thailand and Burma, an area that’s quite infamous and that’s the Golden Triangle. What that person’s just selling bits and pieces basically. Just trying to make a few bucks to buy some food, to pay rent, do all the things that we all do. YOUNG: What sort of things would be on sale there? What would you pick up there? Not that you would. BROWN: You could pick up anything. I found a rhino, a complete rhino horn which is extremely rare to find a complete one and they wanted eight and a half thousand U.S. which sounds a lot, but if I was a dealer by the time I got that to Hong Kong or the Middle East or Singapore or something like that it would be a hundred and twenty, a hundred and thirty thousand U.S. So it’s serious money at stake.

|