|

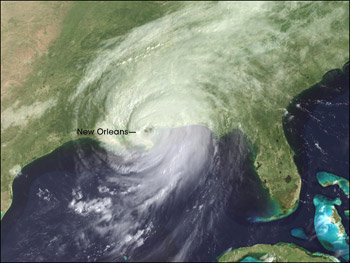

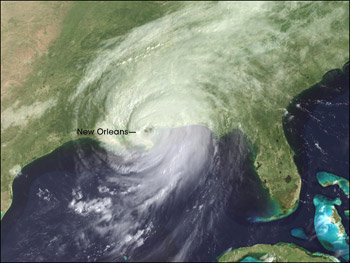

This satellite image from August 29, 2005 shows Hurricane Katrina as it moved over southern Mississippi at 9:02 a.m. With winds of 135 miles per hour, the eye of the storm was due east of New Orleans. (Credit: NASA-GSFC, data from NOAA GOES)

SCHLEIFSTEIN: I can tell you what they did after Hurricane Betsy. And the community was still dealing with it today. They had re-opened an old garbage dump and they had burned everything and dumped all the ashes and a bunch of waste into that dump and then reclosed it. And then a couple years later they went back, covered it up and built public housing on it. And then it turned out that it ended up being a designated Superfund site because they found all sorts of toxic materials at the top. I guarantee you that they're not going to do that again. Things have progressed dramatically in terms of environmental protection for wastes of this kind.

I would not be surprised if they end up burning quite a bit of material, but the biggest question is going to be how much material there really is? If indeed 80 percent of the housing stock in New Orleans is destroyed, I guarantee you that they're going to have to tear down many, many, many of those houses. And that’s quite a big of material, and there'll be a lot of asbestos in there. It's going to be mind-boggling trying to figure out what to do. Remember when Galveston was hit in 1900, they just leveled it, the entire island, pushed that stuff aside, and poured seven feet of sand on top of it and rebuilt on top of the rubble.

GELLERMAN: Mark Schleifstein, an environment reporter for the New Orleans Times-Picayune, spoke to us from a makeshift newsroom in Baton Rouge.

[MUSIC: Peter Gabriel “Here Comes The Flood,” “16 Golden Greats” (RealWorld - 1997)]

GELLERMAN: Coming up: the strategy behind opening up the nation’s strategic oil reserve. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Related link:

NASA satellite images of flooding in New Orleans Back to top

[MUSIC: The Junkman “What The World Needs Now, Is Packaging, More Packaging” from ‘Junk Music 2’ (Moo Group - 2003)]

[CAR DRIVING BY]

GELLERMAN: It's Living on Earth. I'm Bruce Gellerman.

[CAR HONK]

GELLERMAN: By the time Hurricane Katrina hit here in New England it had just about run out of steam. There was some rain and wind, but the big impact here was at the gas pump.

GAS STATION ATTENDENT: Right now, when the Volkswagon backs out, pull in and you’ll be next…

GELLERMAN: Business was brisk at Jack’s Gas Station in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Usually, it’s cheaper here than most places. But not any more.

MAN: Since last night, it went from $2.71 to what it is now--$3.17)

GELLERMAN: Despite sticker shock, drivers were still lining up; grumbling but resigned to pay up.

WOMAN: I thought it was going to be three dollars and now I’ve come down and it’s $3.17 which is why I came down to fill up. President Bush has to let go of some of what we have in reserve. It will help the problem, it won’t solve the problem, it will help.

GELLERMAN: Well, President Bush did decide to tap the nation’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve and let oil flow into the marketplace. But while it pushed the price of oil down a bit, the price of gas went up. Jason Schenker is an economist and energy analyst for Wachovia Corporation in Charlotte, North Carolina.

SCHENKER: At this point in the game the real problem is with the refineries. There are power outages to the refineries. The fact that you don’t have electricity going to these refineries means even if you can get oil there, you can’t turn it into the products people use. So what we ended up with is the price of oil fell, while the price of gasoline, heating oil and jet fuel continued to rise.

GELLERMAN: So why open up the reserve at all?

SCHENKER: Well, this is really one of the only things that the government can do in order to help the situation. Plus, it does mitigate what otherwise could be an oil price push towards $80. Let us not forget that this did push the price of crude down, which might have otherwise have gone up, even if consumers don’t directly see that benefit.

GELLERMAN: But let me ask you about this Strategic Petroleum Reserve. I understand that it’s located in underground salt caverns?

SCHENKER: Yes. There are different salt caverns spread throughout Louisiana and Texas, and they hold, right now, about 700 million barrels of crude.

GELLERMAN: Louisiana?

SCHENKER: Yes.

GELLERMAN: So did any of it get wet?

SCHENKER: (LAUGHS) Well, that is not really, I don’t think, an issue. These are far underground…some of the most stable geologic formations available. When the U.S. government went to establish this system in the 1970s it used salt caverns because of the security of these caverns.

GELLERMAN: Seven hundred million barrels, huh?

SCHENKER: Yes.

GELLERMAN: We use about, what, 20 million barrels a day?

SCHENKER: Right now, yes, between 20 and 24, somewhere in there. Right now it’s about 21.6 million barrels.

GELLERMAN: So we got about 35 days worth of oil down there.

SCHENKER: Somewhere in that range. It’s not a lot of oil, and it’s sort of a mix of grades. It’s a mix of both higher and lower sulfur content oils.

GELLERMAN: So what are they gonna do? They’re going to pump it out and they don’t have a refinery to refine it. So what are they going to do with it?

SCHENKER: Well, some of it will go to refineries, obviously. But there’s usually time lag. By some estimates I’ve seen it could take up to three weeks from the minute the order’s issued to withdraw oil and then to actually physically remove it.

GELLERMAN: Well, when does it get to, you know, a dangerous point where we’re tapping too much of our reserve?

SCHENKER: Well, I think at this point opening it up is not that big a situation. I think one of the orders went in for 500,000 barrels. Even if we saw a number of millions of barrels come out there, I don’t really think that’s going to be a problem. Again, we’ve been continuously building this SPR for a number of years. We’ve expanded the capacity, and because of that we are now available to use it. This is one of those in case of emergency situations, and there’s probably no better time like the present than to tap those reserves.

GELLERMAN: With the loss of so much crude oil production due to the hurricane, what is the effect of this going to be on the economy?

SCHENKER: Well, there’s a few different things that’s going to happen. One of the things, of course – and again, a lot of this is going to deal with refinery product – is that it’s going to hit consumers. People often say that increases in energy prices disproportionately…well, they function as an energy tax. And I argue that they disproportionately affect the lower income individuals in a given economy, simply because energy expenditures as a percentage of their disposable income is far greater.

And what you can see is – and again, we’ve seen some of this recently – is energy prices have been on a significant bull run for a number of years. We could see, as we’ve seen in the past few months, different large discount chains sort of feeling some of the crunch. We could see some consumer spending come back. This could result in lower than previously forecasted GDP estimates for the third and fourth quarter by a few tenths or so.

GELLERMAN: This hurricane has really destroyed a lot of the petroleum infrastructure in the south.

SCHENKER: Well, although we do find that most of actually the key infrastructure – the Henry Hub is intact, the LOOP is intact, and the pipelines seem to be unaffected – we have had quite a few rigs that seem to be destroyed. Recent reports do show that there are perhaps more than 20 rigs that have been destroyed.

GELLERMAN: What’s the Henry Hub?

SCHENKER: The Henry Hub is where we have the natural gas exchanged nationally and that had actually been closed ahead of the storm and during the storm. And there was some concern that that could be damaged. But, as it turns out, the Hub is fine and reopened.

GELLERMAN: Boy, if this Hub had gone down, in the Northeast here where we use a lot of natural gas, we’d be in trouble.

SCHENKER: Yes, the Hub is critical, as is the LOOP. The Louisiana Offshore Oil Port was also not damaged, or not significantly damaged, which is very important. Offloads of about one million barrels per oil per day occur at the LOOP. And furthermore, this is the only port in the country where ultra-large crude carriers, also known as ULCCs, that carry three million barrels of crude, can unload. It’s the only place they can do it, and if either one of those, the Henry Hub or the LOOP, had been significantly damaged, we would have a much greater energy crisis on our hands.

GELLERMAN: I didn’t realize we were so vulnerable.

SCHENKER: Well, our energy infrastructure is placed in a region that is vulnerable to the weather. This is, of course, an extremely extraordinary storm – this is largest, most catastrophic storm ever to hit the United States by some accounts – and as such, such a rare event is difficult to price into the markets.

GELLERMAN: Well, Mr. Schenker I want to thank you very much.

SCHENKER: It’s a pleasure to have been here with you today.

GELLERMAN: Jason Schenker is an economist and energy analyst for Wachovia Corporation. He’s based in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Back to top

Kerry Emanuel. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

TV ANNOUNCER: And welcome back to our ongoing coverage of the aftermath of hurricane Katrina. I’m Kim Perez…

GELLERMAN: Kerry Emanuel doesn’t usually watch much tv, but as the devastation of hurricane Katrina unfolds he’s been glued to the Weather Channel on the little television he keeps in the kitchen of his home in Lexington, Massachusetts. These days, he’s resisting the temptation to say “I told you so.”

TV ANNOUNCER: Part of the Twin Span bridge on I-10 into New Orleans is gone…

GELLERMAN: Kerry Emanuel is a professor at MIT’s Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. He has a new book called “Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes.” And his latest research, published in a recent issue of Nature Magazine, correlates the greater intensity and frequency of hurricanes with global warming. Even he was surprised by what he found.

| |

Kerry Emanuel. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

EMANUEL: Well I looked at the record of hurricanes in the Atlantic and the western part of the North Pacific, and I looked at a measure of the production of energy by hurricanes over their entire life. When you look at this measure of energy consumption it’s gone up by about 70 or 80 percent since the 1970s. It’s a really big increase. It was startling. And we’re trying to understand why.

Part of it I think we do understand: that when we looked at the whole issue of wind speeds, we didn’t think about the issue of the duration of events. And this particular metric that’s gone up 70 or 80 percent is also depending on the duration of storms, and that duration has gone up quite a bit. It’s gone up about 50 percent in the last 30 years. And that explains part of the difference, but not all of it, to be sure.

GELLERMAN: Well, how close is the correlation between the surface sea temperature and hurricanes?

EMANUEL: Well, this particular measure of energy consumption is very closely tied to sea surface temperature.

GELLERMAN: So, the higher the temperature of the sea surface, the more intense and the greater the duration of hurricanes?

EMANUEL: That’s right. And we predicted that you should see about a ten percent increase in wind speed for every two degree sea change. That theoretical prediction has been backed up since then by lots of modeling that has been done elsewhere by other groups.

GELLERMAN: So what you expected to see was a nine percent increase and you’re actually getting 80 percent?

EMANUEL: Yeah, 70 to 80 percent. So the prediction was way off.

GELLERMAN: So you have scientists who are supplying you with the global warming data?

EMANUEL: That’s right.

GELLERMAN: And you feed that into your models.

EMANUEL: Mmm-hmm.

GELLERMAN: And, so right now you’ve gotten, what, about a five temperature degree increase in the surface temperature of the water?

EMANUEL: That’s right.

GELLERMAN: And it could go up one degree? Two degrees?

EMANUEL: That’s right. The predictions are one to two degrees. Now, ironically, one of the things that isn’t in the models is the feedback to the climate system from hurricanes themselves. We always talk about hurricanes responding to climate change as a one-way proposition--climate changes, the hurricanes respond.

It’s quite possible that it isn’t one-way. It may very well be two ways: that the hurricane activity feed back on the climate system. And one of the ways that that can happen is through the effects of hurricanes on the upper ocean, which is really what motivated my Nature study to begin with. They churn cold water to the surface, and they also export heat in the ocean to high latitudes.

So, one of the theories about this feedback would suggest that the effect of hurricanes on global warming itself would be to reduce that warming in the tropics, but to increase it at high latitudes. We think. And if that happens, then the projected warming at the latitudes of, say, New England or Europe, would be more than what is being forecast. But, the warming of the tropical regions would be somewhat less than is forecast.

GELLERMAN: When you look at the planet globally and you’re looking at hurricanes, what is the effect of man-made warming upon the intensity and duration of the hurricanes we have now, and may have in the future?

EMANUEL: We think we’re seeing a signal that the intensity of hurricanes is going up owing to global warming, and their duration is increasing, as well. And this has us worried. In terms of the influence of this on the rest of the world, I think it can’t be stressed enough that in the United States we have been enormously successful in reducing the loss of life. As horrible as Katrina has been – and it is horrible, sort of a worst-case scenario – so our problem is economic. That’s our big problem.

But in the rest of the world, in the developing world, the problem is loss of life. You know, tropical depression Jean last year – it was just a depression – killed almost 2,000 people in Haiti. Hurricane Mitch in 1999 killed 11,000 people in Central America. And a decade before that, a hurricane in Bangladesh killed 100,000 people. Now, this is really, really terrible, and our suffering ought to be weighed against that.

GELLERMAN: Professor, when you watch the Weather Channel and see the destruction from this Hurricane Katrina, do you say, “I told you so”?

EMANUEL: No, I think we’re not quite that heartless to think that. It’s a terrible, terrible scene of devastation. And I think I speak for my colleagues that, about the time Katrina came off the west coast of Florida and emerged into the Gulf, and the track forecasts were revised to bring it over or near New Orleans, we all felt this terrible sense of dread because people had talked about nightmare scenarios. We sort of played them through in our own minds and in our discussions, and this was certainly one of them.

And on top of that, Katrina’s track took it over a feature in the Gulf of Mexico called the Loop Current, where the warm water that you normally find in the Gulf in the summertime runs particularly deep. And we have known for some years that that’s very favorable for the rapid intensification of hurricanes.

GELLERMAN: So do you expect to see more hurricanes of the sort of Katrina coming our way in the next few years?

EMANUEL: Well, yes and no. Certainly we’re going to a lot of Cat 4 and 5 storms. Whether they hit land, and whether they hit a populated part of the land, is entirely a matter of chance and that makes it impossible to answer your question in a reasonable way.

Let’s just take Hurricane Brett. Now, not too many people, unless you live in Texas, remember Hurricane Brett. It was 1999. It was a Cat 4 hurricane when it went into the Texas coast. If it had gone into Houston or Galveston it would have been horribly devastating.

What really does make a difference, of course, is that the population of these coastal regions has exploded. And people are…their risk is being subsidized by federal policy, and state and local policy, and that is what the real problem is. It’s not meteorological, it’s societal. We’re putting all this wealth in harm’s way and we’re getting creamed.

GELLERMAN: Do you do anything different here, New England, to prepare your house, to prepare your family, for disasters?

EMANUEL: Massachusetts actually is an interesting place. It does have a decided hurricane risk. Right now, it is almost impossible to buy a private insurance policy, homeowner’s policy, in Cape Cod because almost all of them have pulled out. They’ve pulled out because new estimates of hurricane risk in Cape Cod suggested that they couldn’t charge a premium high enough to cover their exposure. The state won’t let them, and even if it did, people probably couldn’t afford it. And so we’re in kind of a crazy situation where very wealthy people on the beach in Cape Cod are being insured by a state insurance pool which was set up primarily to insure the uninsurable poor in inner cities. And guess who’s paying for that? The rest of us.

GELLERMAN: Well, meteorology’s about the prediction business. Looking forward, what do you see happening?

EMANUEL: Certainly I think most of my colleagues would join me in saying the next ten years are going to be a rough ride in the Atlantic, even forgetting about global warming because of these natural cycles. We’re in an upswing and this isn’t rocket science, we just look at the past record and extrapolate it into the future. We’re in an upswing, it’s bound to last another five or ten years. And if we have levels of hurricane activity that we had in the 1940s and 50s we’re in trouble.

Now, what has everybody in my profession so concerned – and we’ve been concerned for decades – is the confluence of a huge upsurge in the coastal population with a natural upswing in the number of storms in the Atlantic. And maybe global warming, you know, if you wait long enough will also start to show up in those statistics.

GELLERMAN: So global warming right now you don’t think is having an influence? Or it is having an influence?

EMANUEL: No, if you look at the global record of hurricane activity, you do see a pronounced upward trend that began in the 1970s, which is very highly correlated with an upward trend in the tropical ocean temperature. And the people who study tropical ocean temperatures believe that this recent upward trend is mostly a consequence of global warming, and that’s why we’re worried that we’re now seeing a global warming signal in hurricanes. But the big near-term problem is demographic and natural.

GELLERMAN: Professor, thank you very much.

EMANUEL: You’re quite welcome.

GELLERMAN: MIT Professor Kerry Emanuel’s new book is called “Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes.” His latest research appears in the magazine Nature. You can find the link on our website, www.loe.org.

[MUSIC: Arvo Part “Lamentate: Spietato” from LAMENTATE (ECM – 2005)]

Related links:

- Kerry Emanuel’s paper in Nature

- “Divine Wind - The History and Science of Hurricanes” by Kerry Emanuel Back to top

GELLERMAN: Just ahead: marrying nature and modern farming in West Marin County, California. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

CHU: Improving your home could also improve your health, especially if you have a history of hypertension.

Scientists at Indiana University found normal household chores - like cleaning and gardening – can significantly reduce high blood pressure. Researchers studied three different groups of adults between the ages of 42 and 63. Eight adults with normal blood pressure, ten with high blood pressure, and ten who could develop high blood pressure if left unchecked.

All three groups were asked to perform pre-determined household activities calculated to burn up to 150 calories a day. On another day, they were told to abstain from these activities. On both days, scientists outfitted subjects with a blood pressure monitor, and an accelerometer, to measure the intensity of their movements.

Those with normal blood pressure experienced no change after a day of housework, compared with a day of rest. But the other two groups showed significantly lower blood pressure levels.

Scientists say their results bolster advice from health experts that to lower blood pressure, patients with high blood pressure should adopt a daily regiment of light, rather than heavy exercise. So instead of heading for the treadmill, consider taking the lawnmower out for a spin. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Jennifer Chu.

GELLERMAN: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

Back to top

ANNOUNCER: Support for N-P-R comes from N-P-R stations, and: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, online at m-o-t-t dot org, supporting efforts to promote a just, equitable and sustainable society; The Kresge Foundation. Building the capacity of nonprofit organizations through challenge grants since 1924. On the web at k-r-e-s-g-e dot org; The Annenberg Fund for excellence in communications and education; and, The W-K Kellogg Foundation. From Vision to Innovative Impact: 75 Years of Philanthropy. This is NPR, National Public Radio.

[MUSIC: The Junkman “Styrofoam Never Dies” from ‘Junk Music 2’ (Moo Group - 2005)]

Cows in Pt. Reyes National Seashore. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

GELLERMAN: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bruce Gellerman.

We tend to think of nature and modern farming as competing, often in conflict. But in West Marin County, California, they're closing the divide. It's a place you can drive by a dairy, past old pick-up trucks and barns, and around the next bend spot Tule elk grazing on open grasslands.

The farms and the elk are both protected by law. That's because people who live in West Marin decided decades ago that nature and agriculture can co-exist and even flourish. Producer Guy Hand finds out that this mingling of the wild and domestic isn't easy, but the results are often delicious.

[CROWD NOISES, BUSES]

HAND: From this Vista Point on the north side of the Golden Gate Bridge, you could easily assume that Marin County is awash in tourists, tour buses, and tony suburban sprawl.

[BUS PULLS UP]

HAND: You'd hardly guess that just to the west, over the freeway and those house-encrusted hills, there's another, very different Marin County.

[CROWD NOISE CHANGES TO BIRDSONG]

HAND: West Marin is as distinct from the frenetic eastern third of the county as our notion of nature is from culture. Here, you'll find oak-studded grasslands, redwood and Bishop Pine forests, streams carrying coho salmon, and beaches crowded with nothing more than fog.

[STREET SOUNDS]

HAND: And small towns, like Pt. Reyes Station, where the status symbol of choice is not the car or the hot tub, but the cow. People here put their faith in small-scale agriculture for food, and also as a way to keep development at bay and nature nearby. That's why you'll find cows not only on the hills, but on t-shirts, coffee cups, baseball caps, and storefront signs for the Bovine Bakery and the Cowgirl Creamery.

[SOUNDS IN CREAMERY]

CONLEY: Milk just has so many components to it, and it's so complex, and every day it's a little bit different.

|

Sue Conley, founder of the Cowgirl Creamery surrounded by her award winning cheese. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

|

HAND: Sue Conley, a founder of the Cowgirl Creamery, makes cheese from the milk of local dairy cows, but also tries to illustrate this faith in mingling nature and culture to the three million annual tourists who come to West Marin and its national park, Pt. Reyes National Seashore.

CONLEY: So we thought it would be good to make the creamery behind glass so that visitors could start to understand the association between the land that they're seeing and the cows on the hill, and then what can be produced from these really high quality fields.

[SCRUBBING SOUNDS IN WATER]

HAND: Today, you can see a couple of workers scrubbing round softball sized cheeses in a brine.

CONLEY: This is the Red Hawk, which is our big, stinky triple cream. The red rind comes from a wild bee-linen bacteria that grows here in Pt. Reyes.

HANLEY: Conley doesn't add the bacteria; it simply floats in on the cool West Marin air, a microscopic mingling of nature and culture.

| |

Cows in Pt. Reyes National Seashore. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

CONLEY: We grow the white mold on the outside and then we wash it off with a salty brine, and the brine encourages this wild bee-linen bacteria.

HAND [TO CONLEY]: It's delicious.

CONLEY: It's delicious, I'm telling you (laughing).

HAND: It took decades of hard work and determination to keep West Marin pastoral, by using zoning laws, creating America's first agricultural land trust, setting aside sensitive land, and establishing Pt. Reyes National Seashore. This faith in the pastoral seems to be paying off. While farmers and ranchers and food producers struggle nationally, here there's a booming local food industry that includes small dairy and beef ranchers, cheesemakers, olive growers, and oyster farmers.

[SOUND OF WATER, MUD]

ALDEN: When you're walking out on the mud you kinda wanna keep your knees bent and slide your toe forward and keep your heal high.

HAND: Drew Alden, owner of the Tomales Bay Oyster Company, is giving me instructions on how to walk out to his oyster beds, fifty yards into Tomales Bay, without falling down.

|

Drew Alden of the Tomales Bay Oysters Company on Tomales Bay. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

|

ALDEN: And what that does is keep your heel from locking into the mud and you can maintain your balance a lot better.

HAND: It's low tide on a beautiful sunny morning, and with a little practice I'm able to slosh my way out to the string of mesh bags sitting on the mud flats. They're filled with oysters. Alden opens a bag and pulls one out.

[SOUND OF GRABBING OYSTER SHELLS]

ALDEN: So there you are. You want an oyster? Sorry I don't have any condiments for you.

HAND [TO ALDEN]: That’s okay.

[SLURP]

HAND: Wow, really good. It has a great flavor.

ALDEN: The interesting thing about West Marin and the way agriculture is conducted here is that it’s, for the most part, not monoculture. You go to the Midwest and you see corn, and it's corn for miles or hundreds of miles. And it’s all monoculture which means that you have to take out all of the other species that live there and then plant your seed. Whereas, particularly in an oyster farm, we live in concert with all the other organisms that live in this farm.

HAND: Alden says an oyster farm actually enhances biodiversity. There's no fertilizer or feed to potentially contaminate the bay; the oysters just live off the nutrients naturally found in the water. And the oyster bags attract other native oysters, barnacles, and mussels, which then attract still more creatures.

ALDEN: Fish come in as the tide comes up. because you've got all these forage species attached to our farm. And then birds come in and chase the fish. So there's all this biodiversity that takes place as a result of this farm being here.

HAND: As Alden talks, I find myself sinking a little too deep in biodiversity.

HAND [TO ALDEN]: How do I get unstuck? I think I'm pretty well grounded here. (laughing)

ALDEN: Okay, bend your knee. Lift your heel.

HAND: Oh, okay.

ALDEN: And pull your toe out.

[REGGAE MUSIC AND CONVERSATION]

FINGER: How you folks doing?

HAND: A few miles up Highway 1, John Finger, another oyster farmer, is talking to some customers.

FINGER: Okay, so why don’t you go get yourself set up in the picnic area and then come back and we'll get you set up with oysters and you’ll be on your way

HAND: Finger's Hog Island Oyster Company produces about three million oysters a year. Business is booming. But this is where this story of pastoral bliss gets complicated. Oysters require pristine water and Tomales Bay is one of only four spots in California clean enough to grow oysters commercially. But the bay is not always clean enough.

FINGER: In 1998, we had 170 people get sick from eating oysters from this bay. From our company and a couple others.

HAND: On May 14, 1998 all six of the commercial shellfish growers in Tomales Bay were closed down for several weeks due to an unknown pathogen. Subsequent studies showed the culprit to be a virus, possibly from faulty septic tanks. But further testing showed that agriculture was adding significantly to pollution in the bay. John Finger:

FINGER: We've done enough studies to know that there are certain streams and certain watersheds that contribute most of the fecal coliform loading into this bay. And the characteristics of those watersheds are that they have ag operations and primarily dairies on them.

HAND: A century ago, dairies were purposely built along the creeks on the hills above Tomales Bay. Those waterways flushed waste and manure downward, away from farms. But nowadays, those same dairies have to fight gravity to keep from tainting the bay. The problem gets worse during California's infamous winter rainy season.

FINGER: During rainy weather the runoff has fecal coliform in it, and the fecal coliform count in the bay goes up and we get closed to harvesting. So if it rains, say, over a half inch in 24 hours we get closed anywhere from four to six days. And if another storm comes in before you get open it just tacks another four to six days on. So you can get some running closures of ten, 15 days.

HAND: Currently, oyster growers on Tomales Bay have to close down their operations about 70 days a year.

[TRUCK ENGINE STARTING]

HAND: Gordon Bennett, a member of Sierra Club's Agricultural Advisory Committee, is taking me on a tour of the pasture lands above the bay. He quickly finds a place with problems.

BENNETT: First of all you see a bunch of cows over there, and right behind them you see what looks like a crack in the ground. And at one time that had trees on it. And the trees have all been trampled and destroyed by the cows. And the cows now can access that creek and all that cow manure and sediment is flowing down the creek, connecting to the tributary and flowing right into Tomales Bay. There's that all over the watershed.

HAND: Even still, Bennett wants agriculture to stay on this land. It's the only way, he believes, to keep the far worse threat of trophy homes and golf courses from taking over West Marin. But his attempt to find a middle ground has not always been popular with his peers.

BENNETT: Very often, people in the environmental movement, like people in any other movements, they tend to often times get very simplistic, and they have a solution that it has to be all wilderness or it's all urban. To go at a project that is much more subtle than that, that doesn't deal with absolutes but deals with balances, is often times much more difficult for people in the environmental movement to understand, appreciate and support.

HAND: That subtle landscape that blends nature and farming, isn't something that corporate agriculture always appreciates and supports either. The belief in a sharp divide between nature and culture is, after all, the rational behind factory farms. Proponents of industrial farming say it can free up land like West Marin for other, more environmentally friendly uses.

EVANS: I think there's a very basic assumption in that statement – that's that agriculture is bad and is detrimental to the environment, and I don't believe that.

|

Fourth generation Marin County cattle rancher David Evans standing in a pasture that he believes is environmentally healthy because of cattle grazing. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

|

HAND: David Evans is a fourth generation Marin County rancher who says the divide between agriculture and nature is a false one.

EVANS: I believe that if you fit the agriculture to the landscape that it is not detrimental to the ecosystem and the environment; that the two can live hand in hand.

HAND: In fact, Evans thinks – and studies back him up – that ranching fills an essential ecological niche in West Marin, where large grazing animals like the Tule elk once shaped the land.

EVANS: So, that begs the question, then, why do we have cattle here? Why not bring in the large herds of elk? And, essentially, this is where the compromise comes in. Large herds of elk in this area, to sustain the grasslands the way they once did would need to exist in very large numbers and be able to roam very large areas. That can't happen now. We have roads, highways, fences, so forth. Therefore, agriculture has been able to step in, keep the relationship that is existing between grass and ruminant animal for eons and maintain the landscape and the stability of that landscape.

HAND: When it became clear that Tomales Bay was threatened by pollution, the environmental and agricultural community did a remarkable thing: they came together. They worked together to created the Tomales Bay Watershed Council and other groups that then began searching for ways to solve the problem. Sharon Doughty is a dairy farmer finding solutions:

[WALKING SOUNDS]

DOUGHTY: See these fencings right here? One time the cows during the winter time just moved through all these areas and, I mean, they're big. And when they're walking through an area that is wet, they will definitely chew it up. And so, we fenced this off so the cows couldn't go through here and it did two things: it not only made it so that they couldn’t plow it up but also we let that grass grow to about a foot, foot and a half, and it acts as a filter strip for any nutrients that might be here. And I think they've found it significantly improves the water quality coming off this hillside.

[WALKING]

HAND: David Lewis, watershed management advisor with the University of California Cooperative Extension, has been helping Doughty and other farmers and ranchers stop agricultural runoff into Tomales Bay.

LEWIS: What you don't realize in looking at it today is three years ago you'd come out here and this would be bald soil, just bare soil just exposed to the rain storms through the whole winter. A lot of nutrients, a lot of bacteria, a lot of sediment was coming off of this lot.

HAND: Lewis says the simple buffer Doughty has created filters the runoff from up to 150 cows. He works in three counties and says that people in West Marin are unique in their willingness to make things right. Lewis thinks it has something to do with their shared sense of place.

| |

David Lewis, Watershed Management Advisor with the University of California Cooperative Extension, helps ranchers keep agricultural runoff out of Tomales Bay. (Photo: Guy Hand Productions ©)

LEWIS: Do people roll their eyes sometimes when they hear somebody say something? You bet [LAUGHS], you know? But, for some reason here, they still figure out later on how to come back together. It's not perfect, and it never will be, and compromise always means that you gave something up. But I think they take the time to get comfortable with their compromise.

HAND: As people in West Marin work hard to find a middle ground where agriculture and nature can coexist, nature itself seems to be working on its own middle ground. The rare red-legged frog is finding a home in man-made farm ponds. Certain native grasses seem to grow better in the presence of cattle.

POLLAN: At this point, to separate out Pt Reyes as a natural landscape and as a cultural landscape, it's almost impossible. They're completely knitted together at this point.

HAND: Writer Michael Pollan has done a lot of thinking about the interface between nature and culture. Pollan, who is in West Marin on a writing retreat, has written several books on the subject, including "The Botany of Desire."

POLLAN: And that's what happens after a period of time in any natural landscape that we have had an influence on. Something new comes into the world, and that is the kind of middle landscape that humans create.

HAND: Pollan thinks that having working farms in beautiful places like West Marin and Pt. Reyes National Seashore might be a good thing. Instead of separating nature and agriculture and thereby hiding the consequences of our food choices from view, here they're on display for everyone to see.

POLLAN: Millions of people come here every year, and reminding us as a culture that there is a way to get our milk and our meat from a place that we regard as so beautiful we'll spend our vacation in it. That's a really important lesson for everybody. If we buy into this idea of agriculture as a sacrifice zone, we're really lost. And so to the extent that this place is a reminder that it doesn't have to be that way is incredibly valuable as a cultural expression.

[RESTAURANT SOUNDS]

HAND: Here, in a West Marin restaurant, I'm reminded, too, that there's never a perfect balance between landscape and food. My friends and I spend as much time debating that balance as enjoying our meal. We mull over how much pollution should be allowed into the bay, when grazing is over-grazing, where organic farming fits in. We feel none of the clarity that comes with words like "pristine," "untrammeled," and "wild." In this middle ground between nature and culture, there are no clear victories or sharp boundaries. But then again, something must be right when a place this beautiful can taste this good.

[MAN IN RESTAURANT SINGS A LINE: “Just remember it’s the farmer that feeds us all.” It’s a great song about…..]

HAND: For Living on Earth, I'm Guy Hand in West Marin, California.

Back to top

[MUSIC: Jesse Colin Young “Ridgetop” from ‘Song For Juli’ (Warner Bros. - 1973)]

[BIRD CALLS]

GELLERMAN: We live you this week just north of Marin County, along the banks of the Russian River.

[MORE BIRD CALLS]

GELLERMAN: Many songbirds call the Russian River home. Ed Herrmann recorded as many as he could. Here's a sampling.

[EARTHEAR: “Russian River Birds” recorded by Ed Hermann from ‘RUSSIAN RIVER BIRDS: North American Free Improvisers’ (Garuda Records - 1998)]

GELLERMAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Chris Ballman, Eileen Bolinsky, Jennifer Chu, Ingrid Lobet, Susan Shepherd and Jeff Young - with help from Christopher Bolick, Kelley Cronin and Michelle Kweder. Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Alison Dean composed our themes. You can find us at loe dot org. Steve Curwood returns next week. I’m Bruce Gellerman. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Ten percent of profits are donated to efforts that help protect and restore the earth. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from NPR member stations, and the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation.

ANNOUNCER2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea. Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment. The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs. Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

| | | | | | |