January 18, 2013

Air Date: January 18, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Chemicals That Promote Obesity Down the Generations

View the page for this story

Diet and exercise are seen as the key factors that cause obesity, but new research suggests that certain chemicals called obesogens contribute to the global weight problem. Bruce Blumberg, professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California at Irvine tells host Steve Curwood that the effects of an obesogenic chemical he studied seem to persist for several generations. (07:25)

A Troubling Climate Assessment

View the page for this story

The US government has released its third National Climate Assessment for public comment. This comprehensive report finds humans unquestionably responsible for recent climate disruption, and warns that global temperatures could rise as much as ten degrees by 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions go unchecked. Host Steve Curwood talks about the climate report with Carol Browner, President Obama’s former director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy. (07:10)

Working Woodlands for Carbon and Cash

/ Ann MurrayView the page for this story

Nearly three-quarters of Pennsylvania's woodlands are still in private hands. As Ann Murray reports, the Nature Conservancy has helped develop a program to persuade land-owners to preserve forests by rewarding them for the carbon the trees sequester. (05:35)

New York Times to Close Its Environmental Desk

View the page for this story

The New York Times has decided to shut down its environmental desk, though the paper says the change won’t reduce its coverage of the environment. Host Steve Curwood discusses the Times’s decision with Dan Fagin, who teaches at New York University and is former president of the Society of Environmental Journalists. (05:50)

Overly Honest Science Methods

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

A new twitter hashtag is pulling back the curtain on some of the truths that drive decisions in scientific labs around the world. It’s called #overlyhonestmethods and scientists can’t seem to get enough. Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald reports. (03:30)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

We dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear from our listeners. (01:55)

Wired Wilderness

/ Adelaide ChenView the page for this story

In a novel experiment, artists have set up cameras that beam images from a nature reserve to San Jose's airport. Adelaide Chen reports that over time, they hope to show climate change in action. (07:30)

Right Whales in the Wrong Place

View the page for this story

A Right Whale mother and newborn calf have been spotted in Cape Cod Bay. Whale and Dolphin Conservation Biologist Regina Asmutis-Silvia tells host Steve Curwood that Right Whales should travel to the balmy waters of Florida and Georgia to give birth at this time of year. (08:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bruce Blumberg, Carol Browner, Dan Fagin

REPORTERS: Ann Murray, Emmett Fitzgerald, Adelaide Chen

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. New research on chemicals widely used in the environment shows they make lab mice and their offspring fatter.

BLUMBERG: So what we found is that the effects persisted in the grandchildren and the greatgrandchildren and that some of the effects were actually stronger in the greatgrandchildren who had never been exposed. Some of the so-called fat depots were twice as big. Overall, the animals were probably about 15 percent fatter.

CURWOOD: The lessons fat mice have for humans - also finding a way to encourage land-owners to cultivate their trees.

PARRISH: I tell them that - you know - there is money in them there trees! They can be rewarded by sustainably managing their property for quality and for quantity.

CURWOOD: How trees' ability to sequester carbon can also protect water - and earn a return for their owners. We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

Chemicals That Promote Obesity Down the Generations

A TBT-linked fat cell (photo: Bruce Blumberg)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Conventional wisdom says over-eating and the lack of exercise are behind the obesity epidemic in America and much of the world. But that’s not the whole story, according to some new research from the University of California, Irvine, that implicates certain chemicals called "obesogens". Here's Professor Bruce Blumberg.

BLUMBERG: An obesogen, according to us, is a chemical that somehow causes the body to store more fat. And it can do that by making more fat cells, by putting more fat into those cells, or can do that indirectly by changing how the metabolism works or by making you hungrier, or by making you less able to sense that you’ve had enough to eat.

CURWOOD: Bruce Blumberg is a professor of developmental biology at UC Irvine. And here’s the startling part of his research. Not only has his team confirmed earlier work showing that certain persistent organic pollutants can act as obesogens, they’ve also found that initial exposures can echo down through at least three generations to make animals fat. This study used the chemical TBT – tributyltin – which was widely used as anti-fouling paint until a few years ago.

BLUMBERG: So we exposed pregnant mice to very low doses of tributyltin, and we knew from our previous work that would give us an effect on the babies that were so exposed - that would be - we would call that the F-1 generation. And we asked the question what happens if we bred those babies and the babies of those babies and checked whether there were subsequent effects.

CURWOOD: And what happened?

BLUMBERG: So what we found is that the effects persisted in the grandchildren and greatgrandchildren. And that some of the effects were actually stronger in the greatgrandchildren who had never been exposed.

CURWOOD: So how much fatter were these animals compared to your controls?

BLUMBERG: It depends on which part of fat we looked at. So the effect on fat on different parts of the body was different, but some of the so-called fat depots were twice as big. Overall, the animals were probably about 15 percent fatter.

CURWOOD: Now this study is lab mice, how well do you think these findings might translate to humans?

BLUMBERG: 100 percent.

CURWOOD: Really?

BLUMBERG: The reason I say that is because tributyltin - TBT - works through a hormone receptor called PPAR gamma. And we know there are pharmaceutical drugs that target that same receptor that make people fat. So if I have a chemical tributyltin that activates the same receptor, you would expect the same effect.

CURWOOD: So walk me through the actual physiological process of how a chemical like tributyltin works to become an obesogen.

BLUMBERG: So as much as we know about tributyltin, it activates this hormone receptor PPAR gamma, and PPAR gamma works as a...it has a partner. So it works as a dimer. It has two parts. And the other part of that is called RXR, retinoic X receptor. So if TBT happens to get into a stem cell, and PPAR RXR gamma is there, it activates that complex, and it turns on a set of genes that cause the cell to become a fat cell. And along with that comes the ability to store lipids, to store fats. If PPAR gamma is not there, that stem cell will become a bone cell.

CURWOOD: One of the most startling things that’s in your report is your citation of a study that showed eight different species of animals including pets, laboratory animals, and feral rats, living in proximity to humans have become obese in parallel with the human obesity epidemic. And the odds of this being a coincidence was something like 10 million to 1 against.

Dr. Bruce Blumberg (photo: Bruce Blumberg)

BLUMBERG: 10 million to 1. Yes.

CURWOOD: So what does that mean in your eyes about the human obesity epidemic?

BLUMBERG: You can make the argument, if you talk to...the mainstream obesity community will make the argument that it’s all about diet and exercise, calories in and calories out. And I don’t see how you can explain the increase in obesity of animals, including wild animals, by calories in and calories out. It’s got to be something else. It has to be the nature of the calories. It has to be a chemical, an environmental factor, to which they’re exposed to now, that they were not previously exposed to, that underlies that.

CURWOOD: So who’s most susceptible to tributyltin exposure?

BLUMBERG: Tributyltin will make animals and humans fat at any stage of life. We’re particularly concerned with prenatal exposures because that’s where you have the capability to have transgenerational effects. You won’t cause, or we don’t believe that you will...exposing an adult will cause transgenerational effects on their offspring. But we know from our experiments, that exposing embryos to a chemical like tributyltin will cause transgenerational effects.

CURWOOD: So Professor Blumberg, tell me - that I might need a couple notches on my belt - maybe I could blame on my mother or grandmother?

BLUMBERG: I don’t know if you could blame it on them. What your mother or grandmother was exposed to will affect the efficiency with which you handle calories. It’s well known that obese people have more efficient metabolisms. They store a higher proportion of the calories that they eat. Obviously, they do eat more, but they also store more of every calorie that they eat as fat, compared to non-obese people, so that’s an example of what we call metabolic programming.

CURWOOD: So what does that say now thinking of our social policy in dealing with human health and obesity?

BLUMBERG: It says to me that the most important way that we can change obesity is not by treating obese people, but by preventing them from becoming obese in the first place, by preventing these exposures, which can include chemical exposures, but it can also include exposures to improper diet. There’s a fair bit of data that says exposing mom to a high fat or junk food diet makes the babies prefer that kind of food. There’s some kind of a programming event that’s not well understood that’s going on there. So it’s not just chemical exposures. Chemical exposures and dietary factors, and the nature of diet early in life, is the area that needs to be addressed to make inroads into solving this obesity problem that we face today.

CURWOOD: And what about the folks who are already chubby?

BLUMBERG: Well, it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t help them, but I think that we’re better off preventing them from becoming chubby. You know, there’s a lot of data out there that suggests that 90 percent of people who lose even a significant amount of weight will gain it back. That’s also a very important factor here. Imagine you’re a person who has worked very hard; you’ve dieted hard; you’ve exercised hard; you’ve lost 150 pounds. You look and feel better than you ever have in your life. Why is it a 90 percent probability that you gain that weight back?

CURWOOD: And the answer is?

BLUMBERG: The answer is to me that it’s not strictly behavior. It’s a metabolic programming, that your body is programmed to behave in a certain way, by your early life experiences, and that it’s very difficult to fight that.

CURWOOD: Dr. Bruce Blumberg is a professor of developmental and cell biology at the University of California Irvine. Thank you very much professor.

BLUMBERG: You’re welcome. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Professor Blumberg’s paper in Environmental Health Perspectives 1.15.2013: Transgenerational Inheritance of Increased Fat Depot Size, Stem Cell Reprogramming, and Hepatic Steatosis Elicited by Prenatal Obesogen Tributyltin in Mice

- More about Prof. Bruce Blumberg

[MUSIC: “The Last Thing On My Mind” from Shazam (A&M records 1970)]

A Troubling Climate Assessment

Projected Losses of Arctic Sea Ice and Polar Bear Habitat May Be Reduced if Greenhouse-Gas Emissions are stabilized. Sunset over sea ice on the Arctic Ocean, (Jessica Robertson, USGS.)

CURWOOD: The U.S. government recently released a draft of its third National Climate Assessment, saying that human activity is the primary cause of climate change. The report warns that if emissions go unchecked global temperatures could rise as much as ten degrees by the end of the century. It also details the impacts global warming is expected to have, and has already had, on American lives.

Carol Browner is a distinguished senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. A former head of the EPA, she served President Obama for two years as the director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BROWNER: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, Carol Browner, what’s most important about this assessment?

BROWNER: Well, I think what this assessment tells us, yet again, is that something is happening; something quite dramatic is happening, something that requires our attention. It’s getting hotter. The storms are getting worse. And there’s a huge amount of scientific consensus about the need for action.

A number of ocean front homes were destroyed or severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy on Fire Island, NY. The photo shows what remains of houses in the community of Davis Park. (Photo: Cheryl Hapke, USGS)

CURWOOD: The report seemed to amp up the certainty though from earlier versions that talked about very likely to - to hey humans really are the principal cause. What do you make of that?

BROWNER: I think that’s right. I think that the scientists do what scientists do. They continue to study and this time what they’re saying to us is the science is even clearer that it is human activities that are contributing to these changes in the climate and that we need to do something. Now obviously, this is a draft assessment. It will be subjected to public comment, and then they’ll issue a final report. But it seems highly likely that the final report will take this very significant step up saying that science is just increasingly clear, and that we need to act.

CURWOOD: What immediate action do President Obama and the Congress need to take on climate change given the findings of this comprehensive report?

BROWNER: Well, I think it’s important to know the President has taken some action. Certainly the work he did with the car companies to establish the first ever greenhouse gas emission fuel efficiency standards. They’re hugely important in getting some reductions in that industry. I think the next step is obviously smoke stacks and there the administration has proposed standards for new smoke stacks, new power plants. I think the real issue is existing power plants, and I think we will see the administration propose something and the EPA take action. And to the degree in which we can achieve real and measurable reductions from fossil fuel burning power plants will be important in terms of starting to bend down, if you will, the level of emissions.

Carol Browner, a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress and President Obama’s director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy from 2009 to 2011. (Photo: wikipedia.org)

CURWOOD: There’s one call for action for the President from advocates who say that the Keystone XL Pipeline should not go forward. That would move the produce of tar sands into the market and into the atmosphere, and would, they say, have a strong effect on climate disruption. What sense does it make for the government to support this project, given this climate assessment’s predictions?

BROWNER: The question in front of the administration is the actual siting of the pipeline. I suspect that the State Department who has the ultimate decision-making will look very, very carefully at the sites that have been proposed. But, you know, the concerns that the activists raise are legitimate concerns, which is, we’re going to take a fuel that will only contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, and extract it, and ship it.

CURWOOD: The activists are pointing to the Keystone XL Pipeline controversy as a litmus test for the President. They say, if he’s really serious about addressing climate change, he won’t let his administration go forward with facilitating the extraction of tar sands.

BROWNER: I don’t know if one single decision is a litmus test. I think you have to look at what he’s done, what he is prepared to do. I think this is a president who has believed we have a real opportunity to change our energy, that we create a clean energy future. We’ve seen huge investments in renewables. We’ve seen growth in renewables. Obviously all of us would like to go more quickly. But we are starting to make measurable progress and I think the President will do more things in his second term.

CURWOOD: So if you were still at the White House, running energy and climate policy, what would you say the United States now has to do to protect its people and economy from what’s coming, in terms of climate disruption?

BROWNER: I think we have to do two things. One, we have to continue to reduce emissions. I think we also have to begin a very serious and thoughtful conversation about resiliency and adaptation. I would prefer we didn’t get to this place, but the reality is we need to begin to think through...and storms like Sandy are certainly reminders. How do we redevelop in the case of Sandy - rebuild. How do we develop into the future to ensure that what we now understand are likely to be a climate impact won’t cause us to invest poorly, but rather that we think about these challenges and we invest accordingly. So for example, you don’t build in a flood plain, you don’t destroy marshes in a flood plain, because those marshes actually do a really good job of absorbing a storm surge. Nature’s pretty good at helping itself out if we allow it to.

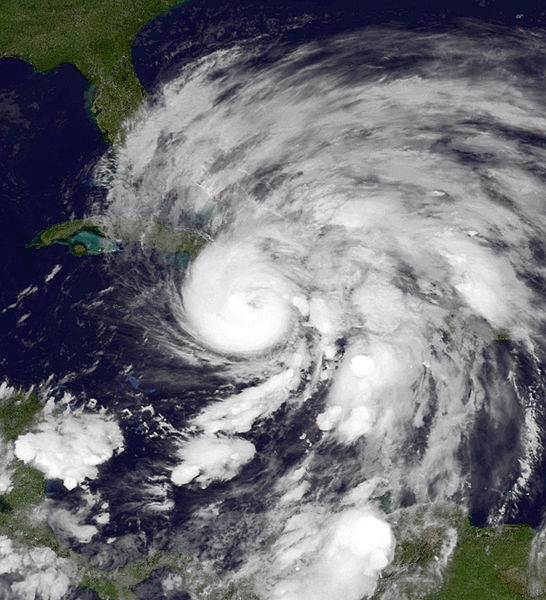

Hurricane Sandy near peak intensity on October 25, 2012. (Photo: wikipedia.org)

CURWOOD: The report points out there are synergies in dealing with these problems. For example, long term emissions reductions may not feel like it has an immediate payoff. But if it comes in the form of reducing pollution, say from power plants, there’s an immediate impact on human health. How do you think the administration should frame these choices, particularly in these times of tight budget constraints?

BROWNER: Well, I think that’s exactly right; that when we reduce emissions from smokestacks and reduce emissions from tailpipes not only will we see climate benefits, but we’ll also see public health benefits. So for example, one of the things the administration did, one of things Lisa Jackson did, was set a new fine particle standard. What we know as tiny fine particles are very dangerous, particularly for older Americans – they can contribute to premature deaths. They’re a byproduct of burning fossil fuels in many instances. So to the degree to which we’re reducing the use of fossil fuels, the degree to which we’re reducing emissions associated with fossil fuels, those reductions have immediate, real, and measurable consequences; in this case, particularly for older Americans.

CURWOOD: Lamar Smith, who is a Republican from Texas, he chairs the House Space, Science and Technology Committee, said after this report came out that he believes climate change is due to a combination of factors including natural cycles, sunspots, and human activity, but scientists still don’t know how much each of these factors contribute to climate change that the Earth is experiencing. In other words, we’re not certain that there’s a problem here. This is a political problem to go ahead. How do you deal with it?

BROWNER: Look, maybe you don’t believe climate change is real, OK? I think it’s real. The President thinks it’s real. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t other reasons to be doing this. There is a green energy revolution in the world. There’s no reason why the United States can’t be at the forefront of that. Why we can’t be making the best technologies, creating the jobs here in the United States and shipping that technology around the world?

CURWOOD: Carol Browner was the climate czar for the Obama administration, and is now a distinguished senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington. Thank you so much, Carol.

BROWNER: Thank you.

Related links:

- Info on the U.S. Global Change Research Center

- The U.S. Global Change Research Center’s National Climate Assessment draft

- More on Carol Browner

[MUSIC: Bomba Estereo “Bosque” from elegancia Tropical (Soundway Records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead . Real life in the world of scientific research revealed through private tweets. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Sample: “Cannery Row” from Carmel (UMG Recordings 1979)]

Working Woodlands for Carbon and Cash

The Nature Conservancy's Mike Eckley uses a prism to identify trees to include in an inventory of the Lock Haven forest. 1000's of small plots will be documented in the 22,000 acre forest. (Photo: Ann Murray)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. When it comes to fighting climate disruption, trees are some of the most effective front line soldiers. An acre of healthy forest can pull as much as three or more tons of carbon out of the air each year, and the bigger the tree the more carbon it can store or sequester in its trunk and roots.

The state named after founder William Penn’s woods – Pennsylvania – has plenty of forests, about 70 percent in private hands. These are now the subject of a value-added program developed by the Nature Conservancy that is designed make money for forest owners while still sequestering carbon and keeping the air and water clean. The Allegheny Front’s Ann Murray has our story.

MURRAY: A Pennsylvania forest has a new, surprising ally. You might even call it a sponsor.

[COMMERCIAL: Meet the Chevy Equinox. And meet a world of new experiences, new places...]

MURRAY: Chevy Equinox is not just a smallish SUV the auto giant is marketing to the young and hip, it’s also paying to keep a forest a forest. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania Water Authority gets paid by Chevrolet for each ton of CO2 that the trees in its 22,000 acre forest pull out of the air and store in their trunks and roots. That’s according to Steve Repach, the authority’s director. REPACH: We’re anticipating, to be on the safe side, anywhere between $75,000 to $100,000 annually. If we get more than that… great. MURRAY: Bethlehem is the first partner in The Nature Conservancy’s Working Woodlands program. A model project that the Conservancy has put together with Blue Source, a carbon credit developer in California. Working Woodlands is one example of what you might call value-added forestry. That is, a way to keep forests healthy while also making money off them.

WILLIAMS: For the landowner they get kind of a one-two punch.

MURRAY: Roger Williams is the president of Blue Source, the carbon brokerage.

WILLIAMS: Several years ago, we began conversations with the Nature Conservancy and the intent was to combine FSC forest certification with the creation of carbon credits for landowners that wanted to participate in that market.

MURRAY: FSC is the Forest Stewardship Council. Timber with an FSC certification can be sold for more than regular wood, kind of like organic for trees. Carbon markets let companies and others pay forest owners to store CO2 to compensate for their own greenhouse gas emissions.

With that in mind, the city of Lock Haven in north central Pennsylvania has just signed on with the Conservancy. Their next step is to take a really close look at their 5000 acre property.

[POUNDING REBAR INTO THE GROUND]

MURRAY: The look begins with an inventory of trees. Forester Mark Banker pounds rebar into the ground to mark one of a 1,000 or so small plots that will be documented. The Nature Conservancy’s Mike Eckley calls out the trees he wants to be measured. ECKLEY: Let’s start with that white pine, right ahead of you. MURRAY: Banker loops a tape measure around the trunk of the tree.

BANKER: 17!

ECKLEY: OK. Alright. White pine, 17 inches.

MURRAY: Eckley records the diameter of the tree and other notes about the tree’s health and timber value into a hand-held device. An independent auditor will come in later to verify the numbers, and will do it again every five or ten years on permanent plots. ECKLEY: Height of three logs. No defect.

MURRAY: The information will help the team decide things like what trees to cut, and when. Computer models will predict how much carbon the forest can store. This is key for the carbon markets this forest is tied to. You can’t just rent out your woodlot to qualify for these programs. You have to prove that you’re increasing the amount of carbon absorbed by actively managing these woods. And you only get paid for the increased amount of carbon your trees store. Josh Parrish runs the Working Woodlands program for the Nature Conservancy.

The Nature Conservancy's Mike Eckley uses a prism to identify trees to include in an inventory of the Lock Haven forest. 1000's of small plots will be documented in the 22,000 acre forest. (Photo: Ann Murray)

PARRISH: I tell them that there is money in them there trees! They can be rewarded by sustainably managing their property for quality and for quantity. The higher quality trees you have, the faster typically they grow. Growing bigger and older trees will sequester more carbon.

MURRAY: Like Bethlehem, Lock Haven is happy about the chance to make money in the carbon market and sell the higher-priced FSC-certified timber. But in both cases their real priority is protecting their watershed. Healthy forests filter and cool streams that pass through them. That’s why the Lock Haven authority has been buying woodlands in their watershed since 1850. There are of course, other benefits to keeping woods around.

MURRAY: Walk on recreation will be allowed under Lock Haven’s new agreement along with hunting, timbering, possibly deep shale drilling. Josh Parrish of the Nature Conservancy says after all, this is the Working Woodlands program.

PARRISH: Conservation has been moving from set-asides to sustainable management, and that’s where our conservation easements are moving; from being “thou-shall-nots” to working with landowners and to manage lands for sustainable harvest, carbon for climate.

The Spring Run Hemlock Biological Diversity area is in one of the plots that will be documented as part of the Lock Haven forest inventory. The run is part of the water supply for the city. (Photo: Ann Murray)

MURRAY: The Conservancy hopes to expand Working Woodlands to other Appalachian states and is currently in China in Szechwan Province. There’s a temporal forest there that looks a lot like the Appalachian woods.

For Living On Earth, I’m Ann Murray in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania.

CURWOOD: Our story on forests comes to us by way of the Pennsylvania public radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about the working woodlands program of the Nature Conservancy in Pennsylvania

- The Allegheny Front Radio Show

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Give Me A Holler” from Nashville (Nonesuch Records 1997)]

New York Times to Close Its Environmental Desk

The New York Times building in New York, NY across from the Port Authority. (Photo: wikipedia.org)

CURWOOD: The New York Times has decided to shut down the nine-person environment desk it established three years ago. The move comes even as the Times was recently praised for bucking the broad media trend in the U.S. of less coverage of climate change. The paper says this decision is designed to cut costs and won’t affect coverage of environmental issues. But many journalists and scientists are doubtful and troubled. Dan Fagin teaches at New York University and is a former president of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

FAGIN: This is a sad, and by now relatively old story in journalism, and that is that newsroom managers are trying to make due with low revenues and smaller staffs. And I do think the Times is making a mistake by dismantling it. But the reasons are pretty obvious, and that is that it’s a cost-cutting move.

Dan Fagin, director of the Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program at New York University and former president of the Society of Environmental Journalists. (Photo: Dan Fagin)

Jill Abramson, executive director of the New York Times. (Photo: wikipedia.org)

CURWOOD: Now the Times has said it still can cover the environment just as effectively without a dedicated environmental desk. How well do you think that will actually work? FAGIN: Well, I think it will be very difficult. I mean, I certainly don’t think the Times is going to stop covering the environment. That would be ridiculous; environmental issues are way too important and the Times has many smart reporters and editors who recognize that. And I especially think the Times will continue to do its big page one projects that are very important and help to set the policy agenda. And they tend to get a lot of attention. I’m much more worried about the daily coverage, the less showy stuff. The Green Blog, we don’t know what its future is. But that blog is important. And I’m worried about the daily beat coverage that goes deeper into the newspaper. It’s really hard to get those stories done unless you have a designated editor, and a designated staff to really push for those stories.

CURWOOD: Talk about what it means not to have a designated editor shepherding those stories through the editorial process at the Times.

FAGIN: If you don’t have an editor or a designated staff, well then you’re, you know...people who are - say - pitching environmental stories to the Times or tipsters, or whoever is trying to convince the Times to do those stories. There’s not really a go-to person. It’s just not as clear how you capture the attention of individual reporters, and how those stories get the kind attention within the organization that they deserve.

CURWOOD: How much do you think that the material that environmental reporting covers, and the reaction of the industry to that material affects the decision of the Times, and the overall decline that you’re talking about, the coverage of environmental news? I’m thinking of the strident campaigning from industry about climate, and sometimes the combative nature of the chemical industry about toxic exposure.

FAGIN: I don’t think that’s a factor with the New York Times, and the reason is the New York Times has the clout. They have the resources. They have the legal backing. They have the firepower to engage in those conflicts if and when they need to resist that pressure. I do think it’s sadly, an important factor for smaller media outlets, and the pressure that comes from interested parties, often industry, is just one more complication that they just can’t handle. So I’m very concerned about that. But I would not want to leave the impression that I think that’s a factor with what’s happening at the Times because I don’t think that it is.

CURWOOD: The Times’ decision to shut down its environmental desk comes just as there’s a major report from the U.S. government saying that we’re looking at a 10 degree rise in temperature, average rise in the temperature, by the end of the century. Ironic, do you think?

FAGIN: Yes. I really do. I mean, it’s crazy when people say that the environment is not a newsy beat. Our beat has never been newsier than it is right now. Climate, of course, is the most obvious example, but it’s certainly true on the energy side too. Look what’s happening with the fracking, hydraulic fracturing. Look at what’s happening internationally with toxics, what’s happening with China, pollution’s impact on its own people in China. So these issues are huge, and we should add, too, Steve, that we’re focusing on the Times because it has been so great. Even if coverage diminishes as I fear it will, it will still probably be the industry leader, at least in the United States among general interest news organizations. It’s that good.

CURWOOD: Dan Fagin, what does the Times’ decision to close its environment desk say about what’s going on with news coverage in general, the newspaper business in particular?

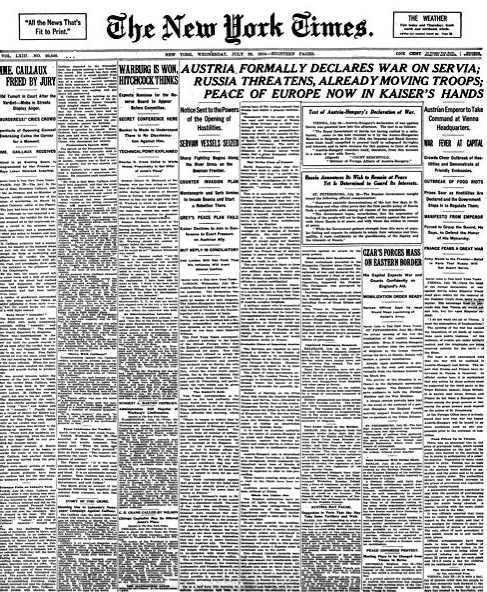

Front page of The New York Times July 29, 1914. (Photo: wikipedia.org)

FAGIN: Yes, I think that’s a really good point. Some people read ideological motives into this decision to close the environmental desk, and I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think this is one element of a much bigger picture, and the bigger picture is that newsrooms are contracting. It’s a fact. When newsrooms contract, specialized coverage often suffers. And it’s not just environmental coverage that suffers. Science coverage is suffering, health coverage, some specialized business coverage...all of that specialized storytelling is at risk. It’s a real danger to democracy, I really feel that it is. So this is just one element of a much bigger story.

CURWOOD: Dan Fagin is director of science, health, and environmental reporting at New York University and a former reporter for Newsday. Thank you so much, Dan.

Fagin: Good to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: We called the New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson for comment. Their Corporate Communications head Eileen Murphy replied.

"Environmental stories", she wrote, "are partly national or foreign, partly economic, etc. and it makes sense to have reporters on all relevant desks covering a wide range of environmental issues. Our coverage of the environment will be as aggressive and comprehensive as it has always been."

Related links:

- Society of Environmental Journalists aggregation of related stories

- “New York Times Dismantles Its Environmental Desk,” Katherine Bagley, InsideClimate News

- “The Changing Newsroom Environment,” Andy Revkin, New York Times

- More about Dan Fagin

[MUSIC: Patricia Barber “Scream” from Smash (Concord Music 2013)]

Overly Honest Science Methods

Twitter webpage. (Photo: bigstock photos)

CURWOOD: When a scientific study first comes out, it’s all about results, results, results. But a new twitter hashtag is giving the twitterati an inside look at some of the methods and reasoning scientists employ to reach their conclusions. It's called #overlyhonestmethods, and it's inspired people in laboratories around the world to share insights into science that aren’t to be found so easily in the textbooks. For example:

MAN: We used enzymes from NEB because the sales rep was nice and gave me free samples.

WOMAN: Healthy control blood was taken from a donor with informed written consent. I know they were informed because it was me.

MAN: Incubation lasted three days because this is how long the undergrad forgot the experiment in the fridge.

The #overlyhonestmethods twitter page. (Photo: Twitter)

CURWOOD: We asked Living on Earth's Emmett Fitzgerald to investigate.

FITZGERALD: The very first overly honest tweet was written by a Twitter user who goes by Dr. Leigh. Since then, Dr. Leigh’s hashtag has taken off, giving scientists a platform to admit to all manner of experimental methods. Now, people throughout the scientific community are taking part, from medical students to chemistry professors.

MAN: Blood samples were spun at 1500rpm because the centrifuge made a scary noise at higher speeds.

WOMAN: The Eppendorf tubes were "shaken like a polaroid picture" until that part of the song ended.

[MUSIC: Outkast “Hey Ya” from Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (Arista Records 2003)]

FITZGERALD: We wanted to find someone to put the tweets in perspective, so we turned to Dr. Janet D. Stemwedel, a former chemist who now teaches philosophy at San Jose State University, and specializes in scientific ethics.

STEMWEDEL: I’ve gotta say my favorite was the one about shaking the Eppendorf like a Polaroid picture until that part of the song was done!

FITZGERALD: Dr. Stemwedel thinks that the tweets reveal genuine dilemmas that many scientists face in the lab. Music can help you pay attention, equipment sometimes does make scary noises, and the scientists themselves are only human.

STEMWEDEL: It’s not a robotic precise work force. It’s real human beings, they have attention spans that wander, they have stomachs that rumble, and being honest about that is kind of nice.

FITZGERALD: Although most of these confessions seem relatively harmless, some scientists are concerned that they may provide ammunition for critics to discredit sound research.

STEMWEDEL: Some scientists might actually worry that if they’re too honest with their methods, this is an opportunity for people with a reflexive distrust of science to come in and say “oh look, these horrible people are wasting our tax dollars doing silly things like dancing with their Eppendorf tubes in the lab.”

FITZGERALD: But Dr. Stemwedel says that certain people will have a bone to pick with science no matter what. At the end of the day, the tweets give us unique insights into the scientific process that we’d never be able to get from an academic article.

STEMWEDEL: They’re showing us a window into the human side of how the knowledge gets built. Scientists not only have a commitment to building reliable knowledge about the world, they have a sense of humor.

FITZGERALD: So the next time you read about a new discovery, remember, it may have taken a whole squad of scientists in a lab somewhere shaking test tubes along to their favorite song to make it all possible.

For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett Fitzgerald.

CURWOOD: You can find a link to #overlyhonestmethods at our website, LOE.org

Related link:

Overly Honest Methods

[MUSIC: Outkast “Hey Ya” from Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (Arista Records 2003)

CURWOOD: Coming up: Two weeks old and twelve feet long—the miracle of a baby right whale in the wrong place. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Herbie Hancock: “Watcha Waitin For” from trio 77 (CBS/Sony Records 1977)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems; The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[LETTERS THEME]

CURWOOD: Time now to dip into the mailbox. Several listeners liked our special program on the 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, and especially the interview with William Ruckelshaus, the first EPA administrator. Ilil Carmi from Berkeley California commented, "How refreshing to hear a Republican speak sanely of government and environmental protection."

But he was disappointed that we failed to discuss fracking as a potential emerging threat to water quality.

Our report on the solar and human powered tricycle the Elf spun many comments on our website as well. Several listeners were interested in getting one – once the price comes down to about $1000.

And finally, our BirdNotes have been setting some listeners all a flutter. Our story about Laysan Albatrosses on Midway Atoll prompted this call.

LANE: Hi, I'm Captain Lane of the Georgia Army National Guard. and I listen to WGA in Athens, Georgia. In the show today, you all talked about the Albatrosses on Midway Island. But there was no mention of the trash that’s causing hundreds, perhaps thousands to die each year for attempting to digest 27 bottle caps and a cigarette lighter. It seems they mistakenly like to dine on the Pacific Ocean’s patch of plastic garbage, now said to be the size of Texas. You should probably mention such on a show called Living on Earth so we humans might come to understand how we are collectively killing the ability to Live on Earth. Maybe, just maybe, enough folks will wake up and smell the coffee before Mother Nature and the Earth disown us all. Keep the calls and emails coming to comments@loe dot org. Once again, comments@loe.org. And you can call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988. And you can comment on our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth.

Related links:

- The Clean Water Act 40th Anniversary Special

- The ELF Solar Tricycle

- Birds Love Suet

- Midway Atoll Albatross

Wired Wilderness

Artist Freya Bardell of Greenmeme with an image from the 'ridge cam' on the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve. (Josko Kirigin)

CURWOOD: Artists have long understood the power of the image to engage and demonstrate abstractions that can be hard to grasp. That's the idea behind a new public art installation at the San Jose airport in California. It's part Ansel Adams and part science experiment. Artists are taking real-time photos of natural landscapes to document the impacts of climate change on a private ecological reserve. From Silicon Valley, reporter Adelaide Chen has the story.

[PADLOCK OPENING]

One of the display cases at the Mineta San Jose International Airport. (Adelaide Chen)

CHEN: Tucked away in the mountains on the outskirts of Silicon Valley is the newest University of California field station, the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve. But it’s not a public destination. It’s 3,300 acres of open space set aside for research.

[DIESEL TRUCK IN BACKGROUND]

CHEN: At the steering wheel of an old Dodge truck is Freya Bardell. She and partner Brian Howe are part of an artist duo known as Greenmeme, the first artists-in-residence at the reserve.

BARDELL: Now we can take a look at the cameras if you'd like.

CHEN: Yeah that would be great.

[CAR DOOR SLAMS SHUT AND TRUCK TAKES OFF]

CHEN: Together with a scientist and software programmer, they’re building a public art project which aims to make climate change visible through the eyes of impartial observers–cameras.

[TRUCK DOOR SLAMS SHUT OVER THE DIESEL ENGINE MOTOR]

CHEN: They’ve set up the cameras to capture high-resolution images of landscapes on the reserve which upload to a server every three minutes. These files are a visual dataset which can be studied later for patterns.

BARDELL: We wanted to look at biological systems and how nature is communicating climate change and how it's happening all around us and we just don't always necessarily know how to read the messages.

CHEN: They hope to find visual cues over time. For instance, global warming could cause trees to migrate up the mountain ridge, or cause a visible change in the fog that regulates coastal and inland temperatures.

BARDELL: Such an amazing resource. Sort of untapped in a way.

[TRUCK ENGINE TURNS OFF]

CHEN: To get to the cameras, the artists have to walk through a field of dry yellow grass towards a muddy pond.

The 'pond cam' snaps a digital photo every three minutes to document the landscape particularly as it relates to climate change. (Greenmeme / Blue Oak Ranch Reserve.)

[WALKING THROUGH DRY GRASS]

CHEN: It’s a calm natural setting until you spot the solar panel that powers a wireless modem and a microcomputer controlling the camera.

BARDELL: So we’re going down a little deer path.

CHEN: Bardell heads towards a towering bush that camouflages the camera. The pond cam sits on a wooden platform protected by a weatherproof case. It’s a perfect place for a year-round postcard view.

BARDELL: Seasonally it changes really dramatically. It goes from this gold in the summer to green grasslands and wildflowers. So it goes through this kind of cycle of color that will also be reflected in the pond. And then in the foreground is where we hope to capture some of the wildlife.

CHEN: Bardell’s especially interested in a threatened amphibian, the California red-legged frog. She’s heard it...

BARDELL: When I was walking along here I heard all these plops. Plop. Splash. Plop.

CHEN: Yet in five years of visiting the reserve, she has never seen this elusive frog. Now it’s the camera’s job to capture these images and bring them to the public’s attention.

[SOUND OF VOICES, PEOPLE INSIDE INDOOR FACILITY ON RESERVE]

CHEN: Few people get to visit this private reserve, but in this modern barn which serves as the main building, there’s a group having a close encounter with a rattlesnake.

[RATTLESNAKE RATTLING]

CHEN: Its head is firmly secured in a tube and guests are stroking it. The tagged rattlesnake is one of 80 research projects conducted here since this land was donated to the University of California system five years ago. Reserve Director Mike Hamilton has been here for all of them but he says this first public art project is special.

HAMILTON: Well, I'd say it's Ansel Adams on steroids (LAUGHS). It's fixed images times an infinite amount of time. Because we're slicing the movement of time into three-minute chunks that then are captured permanently in an archive that now can be compressed and presented to us in a way we don't normally see nature.

CHEN: And while the public can’t set foot on the reserve, they’ll be able to see the images captured by the cameras day or night in a location that’s always open...the San Jose International Airport.

Freya Bardell and Josko Kirigin set up infrared cameras on an airport display case late into the night. (Adelaide Chen)

[AIRPLANES AND SLIDING DOORS TO THE BAGGAGE TERMINAL OPEN]

CHEN: The city of San Jose funded the first two years of the project with revenues from the airport. It’s set up LCD panels in display cases inside the baggage terminal where some five million passengers pass through each year. Brian Howe is Bardell’s partner in this artistic endeavor.

HOWE: The average person will have less than 30 seconds to give it, and if we're lucky, we might have someone for 4 or 5 minutes, you know, waiting around for their luggage. And then there's the occasional person who might be there for a few hours.

CHEN: Howe says they’ve paved the way for future artists to continue and develop their own versions of the project at the reserve for decades to come. But it took years for him to get the experiment off the ground. First there was the funding. Then came the technical part.

HOWE: One of our real major challenges was just the simple act of getting the technology to communicate and how do you get digital SLR cameras to wirelessly send imagery in such a remote location. Everything has to be solar powered. Everything has to be within a Wi-Fi connection.

[DRILLING INSIDE AIRPORT]

CHEN: For the final touch the artists install infrared sensors over the display cases. These will cause the images to move in reverse like a time capsule when they sense movement.

CHEN: One Saturday morning Kaila D’Sa is walking past the baggage carousel to pick up his mother. He stops to take a look at the display cases.

D’SA: It’s a beautiful thing to just see that not only the airport being this big obtrusive platform for big huge airplanes to come in also takes time to give back to the community to say...we also need to preserve certain areas where we just need to let nature do its thing and the birds and bees flourish.

CHEN: The airport prides itself on its certified green building, a clean natural gas fleet and most of its trash diverted from landfills. But most of these efforts aren’t as visible to the public as a display case, with live images that update every few minutes. Over time these images will have the most compelling story to tell about the biggest ecological issue of our generation, climate change.

CHEN: For Living on Earth, I’m Adelaide Chen in Silicon Valley.

CURWOOD: There are images of the installation and the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Green Meme

- Blue Oak Ranch Reserve

- Wired Wilderness Project

[MUSIC: Rhythm of Elements “Airport” from Praia EP (R2 Records 2009)]

Right Whales in the Wrong Place

(Whale and Dolphin Conservation. WDC acquired images under the authorization of NOAA/NMFS, it is illegal to approach a North Atlantic right whale within 500 yards)

CURWOOD: Right whales are so called because they were the right whale to hunt, high in blubber and feeding near the surface, so easy to spot and harpoon. There are now thought to be less than 500 Northern Right whales alive, so scientists were excited to spot a mother and baby recently. But this pair was in the normally chilly waters of Cape Cod Bay, off the Massachusetts coast at a time of year when Northern Right whales give birth down south – off Florida or Georgia. Regina Asmutis-Silvia is senior biologist at Whale and Dolphin Conservation in Plymouth, Massachusetts and she joins us to explain what's going on with these wayward whales.

Wart with her newborn calf. (Whale and Dolphin Conservation. WDC acquired images under the authorization of NOAA/NMFS, it is illegal to approach a North Atlantic right whale within 500 yards)

Wart’s calf won’t be named until it develops distinctive markings. (Whale and Dolphin Conservation. WDC acquired images under the authorization of NOAA/NMFS, it is illegal to approach a North Atlantic right whale within 500 yards)

Wart has been known to scientists for several years. (Whale and Dolphin Conservation. WDC acquired images under the authorization of NOAA/NMFS, it is illegal to approach a North Atlantic right whale within 500 yards)

(Whale and Dolphin Conservation. WDC acquired images under the authorization of NOAA/NMFS; it is illegal to approach a North Atlantic right whale within 500 yards)

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: We don't normally see Right whale mothers and calves in Cape Cod Bay until April so this is the first confirmed sighting, I believe, we have of a mother and calf Right whale in the bay 27 years of data collection. We know they normally give birth in warmer waters off Florida and Georgia and maybe even the Carolinas, as far north as there. But we also know that the water temperature here is a lot warmer than we would expect this time of year. And it’s probably closer to April kind of water temperatures. So possibly, if there’s something triggered by water temperature and it’s a little warmer here, she might have thought it’s OK to have a calf here.

Regina Asmutis-Silvia is a senior biologist at Whale and Dolphin Conservation. (Photo: Regina Asmutis- Silvia)

CURWOOD: Yes, this has certainly been a mild winter so far. And 2012 is now in the record books officially as the hottest year ever recorded. So how likely is it do you think that the climate has changed enough that Cape Cod Bay perhaps is now an appropriate maternity ward for Right whales this time of year?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: I think that would be scary on a number of different levels because not only are Right whales critically endangered because of human impacts on them – vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglements, habitat degradation, noise pollution, chemical pollution – they have a whole lot of stuff that’s going against them. And we know they’re viable...they can calf, clearly...we just saw one. But they feed exclusively on zooplankton, these tiny little copepods, these tiny little animals that tend to be a very cold water species. And Cape Cod Bay is a place where they’re supposed to come and eat. So if the water temperature here is warm enough for them to calf, what that would probably mean is that it’s not going to be cold enough for them to come here and feed.

CURWOOD: Now what about the nuclear power plant there in Cape Cod Bay? The Pilgrim nuclear facility empties its wastewater into the bay, and that water comes out to be some 32 degrees warmer than the water in the bay as a whole. What effect might that have to the whales’ ability to calving in Cape Cod in January?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: There’s certainly a lot of speculation. I think about what the impacts of the power plant are on the bay in general. There’s different kinds of chemicals they might use to clean aspects of the plant that are getting put out there. There’s some levels of radiation that are theoretically going out there. So I think the plant’s been operating for, I think, since the 70s...40 years or so. So I’m not sure that in itself is what would be attributed to this calving event because if it was the plant operating, it’s been there for so long that we would have seen this earlier.

Having said that though, because there’s a newborn calf there, and because the calves are exclusively feeding on the mom, and whatever toxins the mom builds up she dumps immediately into the calf through her milk, having a newborn calf in a place that has potential pollutants in the water is tremendously scary.

CURWOOD: Now this mother whale in question is known to scientists, I believe, by the name Wart, and at one point, she got all tangled up in fishing gear that scientists eventually freed her from. Can you tell me more about that?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Well, fishing gear entanglements are one of the two biggest threats to these animals, and it’s what we call fixed gear, fishing gear. So it’s things like lobster gear or crab gear, gillnet gear, whatever’s set to fish and stays in the water for some period of time before it’s hauled again out.

And the animals as mammals; they’re feeling very much the same kinds of things that we are. And the average time of death of an entangled animal is about six months. They typically die of some infection that they’ve acquired from the gear actually ripping into their skin, or starving to death because they can’t feed. And it’s a real long and slow and painful way to die.

They tried for a couple of years to get the gear off of Wart unsuccessfully. And their last attempt, and successful attempt, was in 2010, and they were able to remove the gear from her, but then they never saw her again. And so it’s a victory on a number of levels to have seen her here, not only because she’s obviously survived the entanglement, which is thrilling in itself, but also because she’s had a calf. So she’s healthy enough to have a calf and that’s another addition to this critically endangered population. So it’s a big deal sighting on lots of levels that it’s her.

CURWOOD: So what’s the name of Wart’s baby?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: That whale won’t get named for a while. Right whales are individually identified by a unique pattern by what are called callosities, roughened patches of skin almost like callouses that are on their heads and on their chins and behind their blowholes. And it’s very similar to the places where we would grow facial hair.

And so they develop these big roughened patches of skin as they age a little bit. When they’re born, those patterns, those callosities, have not erupted yet. So this calf, less than two weeks old, doesn’t yet have those individually identifiable marks. Those callosities haven’t erupted. The calf’s going to stay with its mom probably for about 10 months to a year. So during that time, that pattern will erupt and be identifiable and be documented. And then, over a couple of years, once it’s stable and the whale can be identified on its own, that’s when it’s going to get to get named. Not quite yet.

CURWOOD: But no nickname yet, huh?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: No, not allowed.

CURWOOD: (laughs) So how did you find this pair of whales? And what was your reaction when you discovered it was Wart, and she had a new baby?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: I probably can’t say the reaction on the radio. The FCC won’t let me do that! But we went out to actually go see or find what we thought was potentially an injured or ill pilot whale. And based on the descriptions, we were told there was a 12-foot whale that was hanging around near some of the marker buoys in Plymouth Harbor.

When we saw something that was dark and at the surface and small, but it just didn’t seem like a pilot whale, I stopped the boat and kind of watched for a little while. And then said things that I can’t say on the radio. And then I called NOAA for authorization to approach it because there’s an approach distance that you’re not allowed to go near Right Whales. And I think they were equally as shocked that I would be calling about a mother-calf pair because that’s not where they’re supposed to be right now.

So we did approach for confirmation, and then we stayed with them, and we monitored.

The calf stayed at the surface for a long time. We monitored the mother’s respiration rates. We tried to look to make sure there wasn’t any gear on her, that she didn’t appear injured, and they sent a plane up and documented to tell us she was free of gear, and that she was fine. And then they were able to identify her as Wart. So it was very exciting.

CURWOOD: And just how big is Wart, by the way?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: She’s a big girl, so probably somewhere between, you know, close to 50 feet long. And the calf is very, very small – probably is only about 12 feet long. So like I said, it’s a very, very young calf.

CURWOOD: How cute is this baby whale?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Oh my God, it’s adorable. To the point where it’s very vulnerable. It’s kind of one of those mixed feeling things where you look at it and you realize just how vulnerable that animal really is, and what a difficult road ahead that it has. So it’s mixed feelings of thinking, ‘Wow, it’s really really special and really cute’ to ‘I’m really nervous for this animal and I really really worry about its survival’.

CURWOOD: Regina Asmutis-Silvia is senior biologist at Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Thank you so much.

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: And you can see Wart and her calf at our website, LOE..org.

Related links:

- About North Atlantic Right Whales (Eubalaena glacialis)

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation

[NORTHERN RIGHT WHALES VOCLAIZING IN CAPE COD BAY]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with voices of Northern Right Whales in Cape Cod Bay. These sounds of the Northern Right Whales come to us courtesy of Cape Cod Right Whales recorded by the Bioacoustics Research Project at the Cornell Lab Of Ornithology.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, James Curwood, Meghan Miner, and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic. com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at PaxWorld.com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth