May 17, 2013

Air Date: May 17, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

When You Eat Chicken You Could Be Eating Arsenic

View the page for this story

A new study from Johns Hopkins University updates 2006 research that found excess levels of arsenic in U.S. chicken. In 2009 the Center for Food Safety petitioned the FDA to stop the use of arsenic in chicken feed. The Center’s lawyer Paige Tomaselli tells host Steve Curwood that the FDA has not responded to the petition, so now the Center has filed a lawsuit. (07:05)

Chef Bun’s Sustainable Sushi

/ Annie SneedView the page for this story

Blue fin tuna, wild freshwater eel, and other sushi ingredients are in steep decline due to the popularity as people around the world demand this Japanese cuisine. Restaurant owner and sushi chef Bun Lai says the ancient tradition of sushi must evolve and become sustainable. Living on Earth’s Annie Sneed reports. (05:20)

Lasting Impacts of Gulf Oil Spill

/ David LevinView the page for this story

Three years after the BP oil well disaster, scientists are struggling to understand the effects on the Gulf ecosystem. From Mind Open Media, David Levin (le-VINN) reports on the oil's impact on the tiny creatures that form the base of the food chain. (06:55)

Controversial Dam in Ethiopia

View the page for this story

The Gibe dam in Ethiopia, under construction since 2006, could become the 4th biggest dam in the world. But Philemon Loyeli, a local activist tells host Steve Curwood that the free-flowing river is vital to local people's livelihood and Elizabeth Hunter, from human rights group Survival International, explains that the project would disrupt the annual flooding of the Omo River, and the government is ignoring their plight. (08:30)

BirdNote ® Night Voices

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In spring, woods and gardens ring with song, as birds claim territory, nest and raise their fledglings. But as Mary McCann explains, birds don't just sing by day, there are notable night warblers too. (02:00)

The Wild Weather Book

/ Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

Why stay indoors just because of rain, wind, snow, or ice? A new book, The Wild Weather Book, by Fiona Danks and Jo Scholfield, details activities to get children outside in all sorts of weather. Recently some elementary school students in Massachusetts tested a couple of the projects and Naomi Arenberg joined them. (10:50)

Right Whale in the Wrong Place Update

View the page for this story

North Atlantic right whales ordinarily give birth in the balmy waters of Florida and Georgia but in January a whale named Wart gave birth in the cold waters of Cape Cod Bay. We check in to see how Wart and her baby fared since then. (06:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Paige Tomaselli, Phillemon Loyeli, Elizabeth Hunter, Regina Asmutis-Silvia

Reporters: Annie Sneed, David Levin, Naomi Arenberg, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Research suggests there may be arsenic in the chicken in your pot or on your plate, so food activists have filed a lawsuit.

TOMASELLI: This was based on a report that showed that the majority of supermarket chicken had arsenic residues in it, and 100 percent of fast food chicken that they tested had arsenic residue in it.

CURWOOD: What comes next, and how the FDA responds. Also, three years since the BP oil disaster, scientists still have many more questions than answers about the effects on the ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico.

WETZEL: What we’re wondering is if this continued presence of oil is going to have a long-term effect on a fish's immune system and ability to reproduce, and perhaps some DNA damage effects.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories, and much more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

When You Eat Chicken You Could Be Eating Arsenic

In 2010, 88% of chickens in the United States received feed containing arsenic. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Health concerns have many people in the United States forgoing red meat in favor of poultry, but a new study from researchers at Johns Hopkins University has found excess levels of arsenic in chicken. In 2009, the Center for Food Safety filed a petition, asking the Food and Drug Administration to ban arsenic in the food chain. But the FDA has yet to act, so the Center is launching a lawsuit against the FDA. Lead attorney Paige Tomaselli joins us now from Japan via Skype. Welcome to Living on Earth.

TOMASELLI: Thank you.

Paige Tomaselli (photo: Paige Tomaselli)

CURWOOD: So first, Paige, how does this arsenic end up in the chicken we eat?

TOMASELLI: Well, arsenic is a feed additive. It’s administered to chickens, turkeys and swine as an antimicrobial, so it's in the food that the animals eat.

CURWOOD: Well, when did people begin feeding the chickens and turkeys and apparently pigs arsenic?

TOMASELLI: It started in the 1940s. The first arsenic-based feed additive, Roxarsone, was approved I believe in 1944, and so for the past 70 years, arsenic’s been administered to food animals.

CURWOOD: But wait a second; arsenic is generally a poison. What’s the advantage of using it in chicken feed?

TOMASELLI: Well, arsenic is an antimicrobial. So it’s used to treat parasites in food animals, but it's also used to increase the weight of animals so that they have more feed efficiency, and to change the color of the chicken flesh to make it more appealing for human beings.

CURWOOD: And how common is the use of these additives containing arsenic?

Industrial chicken processing plant (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

TOMASELLI: In 2010, the industry estimated that 88 percent of the roughly nine billion chickens in the United States raised for meat were administered arsenic-based feed additives.

CURWOOD: And what’s the proportion of turkeys and pork that get this?

TOMASELLI: The proportion of turkey and pork is much smaller than chicken. It’s mostly fed to chickens.

CURWOOD: But what are the health effects for humans who eat chickens who have been fed arsenic in their feed?

TOMASELLI: Inorganic arsenic can cause cancer, heart disease, decreased intellectual function and many other problems. Now the amount of arsenic residue in the chickens is not going to directly cause cancer - what it does is it increases the overall arsenic burden that humans suffer from drinking water, eating rice and all the other exposure so we have to arsenic. At one time, they thought that organic arsenic was not as dangerous as inorganic arsenic. But recent studies that shown that organic arsenic, the kind that feed additives are made out of, converts to inorganic arsenic both in the gut of a chicken and in the gut of a human, and so now we're finding that these arsenic-based feed additives are actually exposing humans to inorganic arsenic, which is a known carcinogen.

CURWOOD: So tell me about the petition you filed back in 2009.

According to the study out of Johns Hopkins, approximately 75% of people in the United States eat chicken regularly (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

TOMASELLI: In 2009, the Center for Food Safety, along with the Institute on Agriculture and Trade Policy, filed a citizen petition with the Food and Drug Administration. The ask was that the FDA immediately withdraw all approvals of arsenic-based feed additives for use in animal agriculture. This was based on a report that the institute put out in 2006. It showed that the majority of supermarket chicken had arsenic residues in it and 100 percent of fast-food chicken that they tested had arsenic residues in it. We took this data and we asked the FDA to ban arsenic-based feed additives because of these arsenic residues’ potential burden on human health.

CURWOOD: And what was the response from the FDA?

TOMASELLI: It's been 3 1/2 years and the FDA has not responded to the petition, which is why we filed a lawsuit asking them to immediately respond to the petition. Should they deny the petition then we would consider filing an additional lawsuit for their failure to grant this citizen petition.

CURWOOD: What does the FDA say in response to your original petition and now this effort in court to get them to respond to it? Why so much delay? Why the silence?

TOMASELLI: The FDA hasn't said anything to us as far as the petition is concerned. They have made statements in the media that they're reviewing the evidence. At this point they haven't done anything to respond to the petition, and there's been several significant events over the course of the past couple of years that show the immediate need for them to respond to this petition.

CURWOOD: And what are those events?

Center for Food Safety Logo (photo: Center for Food Safety)

TOMASELLI: Well, in 2011, the FDA tested chicken treated with Roxarsone, which is one of the arsenic-based feed additives. They tested the liver, not the muscle meat most people eat, however, the study concluded that the levels of inorganic arsenic were significantly higher for chickens treated with arsenic than those that were not. Shortly after, in June 2011, Pfizer announced that it would suspend - not revoke, just suspend - the sales of Roxarsone. And as far as we know, the decision to suspend is under internal review. And of course, there’s that recent study that came out showing that the muscle meat actually contains inorganic arsenic as well.

CURWOOD: Tell us about the study out of Johns Hopkins. What actually were their findings, and how that does that influence what you're doing?

TOMASELLI: So the Center for a Livable Future tested chicken muscle - so that’s what people eat, mostly, chicken breast, chicken thigh - and results show that there is an increased risk of bladder and lung cancer. Additional people each year will get certain cancers if all chickens are fed arsenic-based feed additives.

CURWOOD: What is the level of risk here?

TOMASELLI: If people in the United States only ate chicken and it was their only exposure to inorganic arsenic, then there might be an insignificant risk. But the fact of the matter is Americans are exposed to arsenic in a variety of places. They’re exposed in water, they’re exposed because wood was treated with arsenic, they’re exposed in the foods that they eat. So this significantly increases the overall arsenic burden on the population, therefore exposing them to additional cancers.

CURWOOD: So tell me, Paige, why do you think the FDA has been stonewalling you on this for the past three years?

TOMASELLI: I think that there's a lot of industry pressure from the pharmaceutical companies on FDA not to completely ban certain feed additives. Part of the problem is that FDA not only has to deal with the pharmaceutical companies, but they’re also dealing with the factory farming industry that would prefer to have access to all kinds of antimicrobials and antibiotics in order to increase their bottom line. So at the end of the day, this is an effort to continue to promote factory farming.

CURWOOD: So, what advice do you have for consumers about eating chicken?

TOMASELLI: If you purchase organic chicken, you're not going to be exposed to additional arsenics. So my advice is to choose organic or to choose arsenic-free or antibiotic-free chicken at this point.

CURWOOD: Paige Tomaselli is an attorney with the Center for Food Safety. Thanks so much for joining us.

TOMASELLI: Thank you.

CURWOOD: We contacted the FDA for comment. The agency replied, "FDA continues to investigate all uses of arsenic-based drugs in food-producing animals and will take the appropriate action to protect public health."

Related link:

The Center for Food Safety - information about arsenic in chicken

[MUSIC: Reuben Wilson “Back At The Chicken Shack” from Organ Blues (Jazzateria Records 2002)]

Chef Bun’s Sustainable Sushi

Miya's "The Best Sushi South of the Mason Dixon Line," an Americana sushi roll inspired by Southern cuisine and its Native American, African and European roots. (Photo: Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Think sushi and you’re likely to picture a dark red slice of tuna on gleaming white rice. A savory choice for you, maybe, but probably not for the ocean. Bluefin tuna, wild freshwater eel, and other sushi ingredients are in steep decline as more and more people develop a taste for this culinary delight from Japanese cuisine. Some see a possibility - and a necessity - for the ancient tradition of sushi to evolve and become sustainable. One of these people is restaurant owner and sushi chef Bun Lai. Earlier this year, Living on Earth's Annie Sneed went along to learn and taste more.

[FOOD PREPARATION, WASABI STIRRING]

SNEED: On a frosty winter night, chef Bun Lai and his team are at the New England Aquarium in Boston. They peel tin foil from giant platters, revealing hundreds of pieces of sushi, that range in color from neon green to fiery red. Tonight, Chef Bun is delivering a lecture on sustainable sushi and tasty tidbits to illustrate it.

LAI: Tonight I brought five different types of rolls, two vegetable rolls. We’ve got catfish with okra and African spices; squid, squid ink, and broccoli; mussels from New Zealand; broccoli, roasted garlic and Chinese blackbean; sweet potato with kudzu dust and fire ants.

Caged Blue fin tuna in the Mediterranean. (Photo: Greenpeace)

SNEED: Of course, Bun isn’t really serving kudzu dust and fire ants, but eating invasive species is part of his message. Thirty years ago, Bun’s mother started her sushi restaurant, Miya’s, in New Haven, Connecticut. As a teenager, Bun joined his mother in the restaurant’s kitchen.

LAI: Back in the day, it was a traditional sushi restaurant and we served all the types of seafood that are popular today.

SNEED: Chef Bun still works with his mother, but the menu’s changed.

LAI: The reason we stopped serving tuna, shrimp, and a slew of other popular sushi ingredients that everyone expects today, is to be able to show people and to challenge ourselves to see if we can thrive as a business without using those ingredients that are so incredibly destructive on so many different levels.

SNEED: Miya’s menu now features invasive species, such as lion fish and shore crabs, and eight pages of vegetarian sushi. And Bun connects with scientists and organizations like the New England Aquarium to deliver sustainable food.

ANNOUNCER: Tonight is all about making those connections between the ocean and what you’re going to have on your plates later, so please join me in welcoming Bun Lai.

[APPLAUSE]

LAI: Well thank you so much for having me.

SNEED: Tonight at the Aquarium, about fifty people - grandfathers, college students, even toddlers - have come for Bun and his innovative sushi. Bun’s dressed in jeans and a black shirt. He’s in his early forties and doesn’t look the stern sushi master. He slips in jokes in a deadpan tone. If you don’t pay attention, you’ll miss his humor.

LAI: The first thing you should try is the Asian shore crab. You just kind of eat it with your fingers, it’s all finger food here and hopefully it doesn’t bite your tongue. If it does, it’s never broken skin, I’ll assure you.

[LAUGHTER]

SNEED: His audience obediently picks up the little crabs and starts chewing.

[CRUNCHING]

MAN: Certainly unusual. Yeah, it’s tasty!

SNEED: They try it all, from mussels to sweet potatoes.

WOMAN: This is the “Kiss the Smiling Piggy Vegetarian Sweet Potato Roll”.

SNEED: After the lecture, people stick around to talk with Bun, and to score a few more pieces of sushi.

HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT: The sushi was absolutely delicious and I was really excited to hear Bun talk, he’s an inspiration. I’m a high school student who’s really interested in sustainable seafood and following that in college, so it’s really great to have a role model like Bun.

Sushi by Hiroshige in Edo period. (Photo: Wikipedia)

MAN 2: The lecture was very fun. This is the first time I’ve ever tried sushi, I’ve never been very excited about it. It was interesting.

SNEED: Alright, do you think you’ll eat sushi again?

MAN 2: Ah, probably not.

SNEED: The kids were probably least intimidated by Bun’s strange ingredients.

GIRL: The crabs you can eat just like popcorn, they’re really crunchy and good.

SNEED: And the message of eating invasive species hit home.

WOMAN: Oh, I thought it was amazing, this thought of, why don’t we eat up what we don’t want invading? I have to say, I never thought of it that way before.

EVENT STAFF: I have extra plates if you’d like to take some sushi home!

SNEED: Bun knows his unusual version of this very popular cuisine isn’t for everyone.

Chef Bun Lai, owner and head chef of Miya’s. (Photo: Wikipedia)

LAI: Throughout my career, it’s been a situation where often people will walk out because we hadn’t been carrying tuna or shrimp or freshwater eel - the most popular sushi ingredients. So if they don’t think outside the box, they’re not going to think that it’s sushi. But food has been evolving since the beginning of time. In the origins of sushi, when it first started out thousands of years ago, most of the popular ingredients that we eat today and think of as sushi weren’t considered ingredients for sushi anyway.

SNEED: Bun and a handful of other sushi masters are helping that evolution along. He hopes that people leave his lecture not only with a full stomach, but also determined to eat only sustainable sushi. For Living on Earth, I’m Annie Sneed.

Related links:

- Miya’s Sushi

- More on Chef Bun Lai

- The New England Aquarium

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch

[MUSIC: Sushi Bar “Aeroplane” from Lounge (H-Street Productions 2008)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how the tiniest living things in the Gulf are doing three years after the BP oil well disaster. That's just ahead here on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Global Noize “Tokyo Sunrise” from A Prayer For The Planet (GNT Productions 2010)]

Lasting Impacts of Gulf Oil Spill

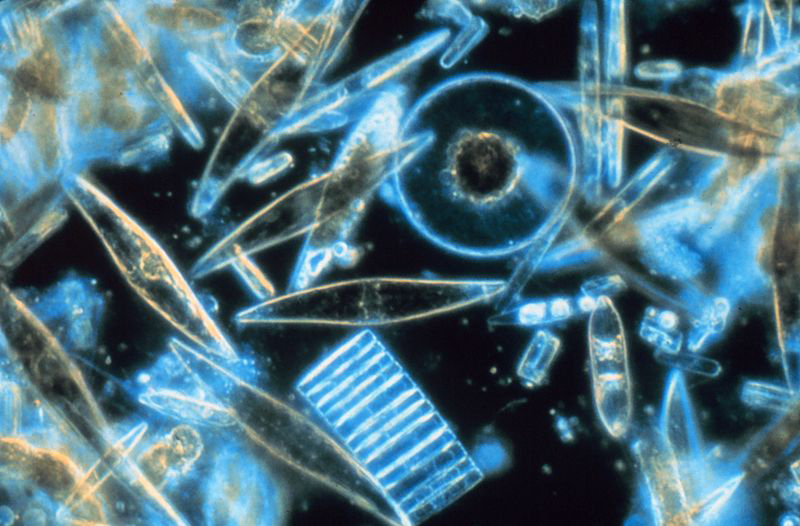

Diatoms are a common form of phytoplankton. (Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Three years after the catastrophic Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, scientists are still piecing together the extent of the disaster. Much of the visible oil from the nearly five million barrel spill has been scrubbed from beaches, but there is troubling news from researchers who study some of the smallest creatures that form the bottom link in the food chain. Biologists and ocean scientists from the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem, or C-IMAGE, have been gathering data about those tiny creatures, and reporter David Levin has been listening in.

LEVIN: For people on shore, the effects of the Deepwater Horizon spill in April 2010 were pretty easy to see. Oil washed up on pristine beaches and wetlands. Ocean life lay dying, covered in sticky brown stuff.

DALY: There was a large mortality of dolphins, sea-turtles, sea-birds—on TV, when you watch those oiled sea-birds, it's just heart-rending.

LEVIN: That’s Kendra Daly, a biological oceanographer at the University of South Florida. When the spill happened, Kendra Daly saw plenty of images like those. But she says her first thought wasn’t about the animals on TV. It was about the tiny organisms in the Gulf called phytoplankton and zooplankton.

DALY: Phytoplankton are small plants, and zooplankton are small animals.

LEVIN: They’re often smaller than sand grains, and even under the best of circumstances, they don’t live very long. Their entire lifespan might be weeks, days, sometimes hours. And after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, Daly says those plankton started dying off fast, in record numbers.

DALY: So something obviously stressed the phytoplankton and zooplankton during that time period, and of course the big suspect is the oil spill.

LEVIN: The mere fact that plankton died wasn’t too surprising, she says - some laboratory studies have already shown that certain species are sensitive to oil. But she says scientists weren’t expecting what happened next. When phytoplankton are sick or near death, they start releasing a sticky, mucous-y substance…

DALY: And so when currents and turbulence push these smaller particles together, they stick together and form larger particles. So you might have a mass of different types of dead organisms that are all glued together with this sticky substance, and so they ultimately become heavier than seawater and then can sink out quite rapidly.

LEVIN: Those sinking particles are called “marine snow.” And it’s natural in the ocean, at least in small amounts. But after the spill, the level of marine snow in some parts of the Gulf went from a flurry to a blizzard. Huge clumps of dead and dying phytoplankton stuck together, mixed with oil in the water, and formed balls of oily, mucous-y goop.

DALY: Yes, [LAUGHS] Long, stringy pieces of goop might be a better way to describe it. What we observed was much higher density of these particles than we typically observe. And the fact that they were oiled - we could see oiled, dark brown particles - that was unusual.

LEVIN: As it sank, that marine blizzard brought oil down with it to the ocean floor, where it slowly collected on the bottom. Less than six months after the spill was officially over, the blizzard had deposited a slimy layer more than eight inches thick in some places.

SCHWING: You get this gelatinous ooze on the sea floor. It’s got the consistency of snot. I mean, it’s really gross stuff.

Patrick Schwing collecting samples in the field. (David Levin)

LEVIN: Patrick Schwing is a Postdoctoral Researcher at USF. The ocean floor is his domain - he studies tiny shelled animals that live in and around the sediments on the bottom. They’re called Foramanifera, or “forams” for short.

SCHWING: They’re single celled organisms. Most of them are in a spiral shape just like a shell you’d find on the beach. Some of them live in the water, some of them live in the mud. Lately we’ve been working with the ones that live in the mud.

LEVIN: As the pulse of oily marine snow drifted to the bottom, Schwing says it settled right on top of where those forams live, putting them in direct contact with the oil - and with all the chemicals inside it. Even dangerous ones.

SCHWING: Yeah, essentially poison to the forams living in the sediments.

LEVIN: In other words, Schwing says, wherever there were thick deposits of marine snow, there were lots of dead forams.

[DOORS OPENING, FOOTSTEPS ENTERING LAB]

LEVIN: In his lab, Schwing shows me just how bad things got. On the table, he points to tiny dishes filled with forams he collected from the seafloor in the Gulf.

SCHWING: What we've been doing lately with the forams is looking at them under a microscope, counting how many are there, who's there, those kinds of questions.

LEVIN: The first dish he shows me is from December 2010, when the layer of marine snow on the ocean floor was still thin. The forams are easy to see even without a microscope. There are hundreds of them in the dish - they look like a tiny pile of sand. But the next dish is totally different. It’s from a sample collected in the same spot three months later, once that oily marine snow had really started to pile up. By then, it was a few inches deep.

SCHWING: Moving to February of 2011, you can see with your naked eye that there's virtually no forams. Six of them in the entire sample.

LEVIN: Six, compared to the hundreds in the other dish.

SCHWING: And that says a lot. You'd expect these guys to be pretty ubiquitous on the sea floor of the Gulf of Mexico.

LEVIN: Schwing says that in some areas, those forams still haven’t come back. And that’s a big problem, because they’re the main food source for a lot of other animals on the ocean floor.

Take out forams, and you starve some species of snails and worms. But the effects don’t stop there.

SCHWING: Forams are eaten by larger critters that kind of root through the mud, and then those critters are eaten by fish, and the fish are eaten by humans.

WETZEL: Well, if you knock out a level of the food chain, it's a cascade effect.

LEVIN: Dana Wetzel is a senior scientist at the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida. She’s investigating how fish from the Gulf were affected by the spill. Wetzel studies oil toxicity in marine life, and says it’s possible that fish feeding near the bottom weren’t just being starved as their food sources died. They were also being exposed to dangerous chemicals as they rooted around for food in the oily muck on the ocean floor.

WETZEL: If you've got a high concentration of oil in the sediments, and you've got fish that either forage in the sediments or make burrows in the sediments, you've increased their exposure levels.

Tiny copepods are just one example of zooplankton. (Wikimedia Common)

LEVIN: She says it’s too early to tell exactly what the oil - or oily food - is doing to those fish. But in many places in the Gulf, the slimy mix of dead plankton, forams, and oil at the bottom doesn’t seem to be going away.

WETZEL: What we’re wondering is if this continued presence of oil is going to have a long-term effect on a fish's immune system and ability to reproduce, and perhaps some DNA damage effects? And is that short-term, is it long-term? These are the real serious questions.

LEVIN: In the end, wiping out the tiny creatures isn’t just an ecological disaster, it’s an economic one. When ocean life suffers, so does the Gulf’s multi-million dollar fishing industry, which has taken a big hit. And that means Gulf residents will be feeling the ripple effects of the spill for years to come.

LEVIN: For Living On Earth, I'm David Levin in Tampa, Florida.

CURWOOD: David's story comes to us from Mind Open Media. To learn more, dive into our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- C-Image home page

- USF College of Marine Science homepage

- USF "Adventure at Sea" blog

- Kendra Daly's Zooplankton Ecology Lab homepage

- David Hollander's lab homepage

- Steve Murawski's USF homepage

- Mote Marine Laboratory

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix “Hey Gypsy Boy” from People, Hell & Angels (Sony Legacy 2013)]

Controversial Dam in Ethiopia

The Turkana people live around lake Turkana in Kenya and Ethiopia. The Gibe dam would seriously affect them. (photo: Survival International)

CURWOOD: One of the oldest alternatives to fossil fuels is hydro-electricity. The Hoover dam, Egypt's Aswan dam, China's Three Gorges dam - these massive facilities control flooding and generate power. They can create economic opportunity but also destroy livelihoods and ecosystems. Case in point - the Gibe dam, on the Omo river in Ethiopia, under construction since 2006, and potentially the fourth largest dam in the world. It's hugely controversial, in part because it would disrupt the Omo seasonal floods that hundreds of thousands of indigenous people have depended on for centuries. Phillemon Loyeli, a local activist, told us why the river’s so vital.

LOYELI: These communities depend on this river, it’s really part of their life. They have thousands years of fishing grounds, and also farming land. This river, it’s like - I remember one of the leaders saying it’s like our cow – you know when they depend on the cow milk? So this river is like our cow that we milk every time and this never gets old, so the government is trying to take our cow and use (it) for itself and now we will be starving.

CURWOOD: What reports have you heard from people you trust at home in Ethiopia about the violence?

LOYELI: The army has been deployed everywhere. You can’t talk anything about the dam. You can’t talk anything against the government. One of my friends whom I know was confiscated of all his electronics, his computers by the state government, and his documents and files were taken out. He’s probably in trouble anyway, and he’s scared even to talk to me because they monitor every step - even his Facebook is under them.

CURWOOD: Well, environmental activists have taken up the cause, among them Survival International. The organization’s Elizabeth Hunter explained that it’s not just the dam that’s a problem, it’s also other actions of the Ethiopian government.

HUNTER: A few years ago, the then Prime Minister Melas Zenawi announced that the government was going to literally take over a whole lot of land in the lower Omo, which is home to several tribal people, and turn it into vast sugarcane plantations. Simultaneously, we also discovered that quite a lot of land down towards the Kenyan border has been earmarked and leased out to private companies where they are embarking on growing things like cotton, biofuels like oil palm, etc.

Karo man crossing the Omo river (photo: Survival International)

Now the only way these plantations are viable is by irrigation from the Omo. And what the function of the dam, one of the main functions, is selling electricity is going to be to regulate the flow, which will enable them to pump water to irrigate these plantations. They will also do away with the natural flood, which the tribal people depended on to plant crops - they call flood retreat cultivation. So it is effectively a double whammy. The plantations, plus irrigation, is simply going to destroy the livelihood of all the tribal people that depend on the Omo.

What is left of parts of Ethiopia's Omo Valley, as efforts begin to redirect the river for irrigation plans. (photo: Survival International)

CURWOOD: What is the projected economic benefit of this dam? What does the government say?

HUNTER: Well, the government has touted this as bringing immense benefit to poor Ethiopians, and it’s also enabling them to make money by selling surplus electricity to neighboring countries such as Kenya. I think the reality is what the dam is doing is enabling a land grab. The government is grabbing land that belongs to tribal people - and they are saying we’re planting sugar with all these biofuels, and this is what’s going to make money. And then the question really is, a lot of private companies stand to make a lot of money on the backs of indigenous peoples and indeed eight to 12 tribes, whole tribes of people again are affected. Can one really call this viable and is it development? I think not. Not without human cost.

CURWOOD: Now how does this fit into indigenous rights there in Ethiopia?

HUNTER: Well, the Ethiopian constitution has several articles; for example, one article guarantees that Ethiopian pastoralists have the right to free land for grazing and cultivation - as well as the right not to be displaced from their own land. There’s another article that says the peoples have the right to full consultation and expression of views in the planning and implementations of environmental policies and projects that affect them directly.

Karo boys above the Omo River (photo: Survival International)

Now the Ethiopian government has simply ridden roughshod over their own constitution as well as such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on the African Charter on Human Rights. And now what is happening because of this program and turnover so much of the land along the Omo into plantations, they have simply gone in there and said, “well, we’re consulting the people.” They’ve held one or two meetings, and people have very clearly said, “we want to remain on our land.”

And where they have met opposition, the government has been incredibly heavy-handed. We’re getting reports of terrible human rights violations. I’ve interviewed and talked to people on the ground who’ve given graphic descriptions of arbitrary arrests, people being thrown into jail, being beaten up. Some people, we got reports of rapes. This is purely because people are standing up, saying, “we don’t want this on our land.”

Karo boy above the Omo River (photo: Survival International)

CURWOOD: What are the ecological consequences of the dam?

HUNTER: They will be very considerable. First of all, because you’ve got the plantations, the government is at this moment destroying the wildlife, destroying the environment to build these monocultures. So it’s going to be catastrophic for wildlife, as of course for the tribal peoples. In fact, the area was declared a UNESCO Heritage Site on both sides of the border of the Omo and Lake Turkana in northern Kenya.

CURWOOD: Who is paying for the construction of this dam?

HUNTER: Well, that’s an interesting question. We know that Salini, this construction company, is building the dam, and that one of the Chinese investment banks is funding the turbine. The World Bank recently announced it was going to fund the power lines, and sort of rather ducked the issue, was economical with the truth, saying it’s not funding the dam, but it’s funding the power lines. Obviously the power lines are an essential part of the dam. So the Ethiopian government has got funding from the international communities. Although it’s interesting to note, both the African development bank and the European investment bank declined to fund the Gibe dam for a number of reasons, and one of them I think was because there was a recognition this is going to be extremely serious for the peoples who live in this area.

CURWOOD: What are the avenues to take this on in court?

Two Karo boys stand above Ethiopia's Omo River (photo: Survival International)

HUNTER: Well, Survival [International] has made a submission to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights because we felt the chances of really getting any justice in Ethiopia was zero. The courts work very slowly, and there are question marks about the independence of judges. And we felt it had reached a stage where this situation is so serious that we’ll soon reach a point of no return. So we’ve gone to the Africa commission. They’re considering that petition now.

CURWOOD: You make it sound like there’s nothing to be done; this is just going to go ahead, these people are going to be displaced. Doesn’t seem like anything’s going to stop them. Or do I have that wrong?

HUNTER: No, actually I don’t agree with you. I know it sounds very bleak. But I do think there is a lot that can be done. And I think a very key point in all of this is public opinion. If enough people put pressure on their governments and the European government, I think we can see some change. For example, I did get news that this very big sugar plantation, which is known as the Couras sugar project, is not as big as it was originally envisioned, that they’ve made a smaller concession. And I think that has been...it’s just an example that they have responded, albeit slightly, to public pressure and international concern. So it is possible to change things.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Hunter is with Survival International in London. Thank you so much, Elizabeth.

HUNTER: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: We contacted the Ethiopian embassy in Washington. You can find its statement in full on our website LOE.org. It reads, in part: "Far from a social and environmental disaster in the making, all the evidence suggests a major and controlled social and beneficial transformation is in process. Certainly, it will impact on the local population and, yes, it will mean changes, but these will provide major improvements in living conditions and the environment."

Related links:

- Survival International website

- Check out Survival’s commentary against the Gibe Dam project

- Statement from the Ethiopian Government on Gibe Dam

[MUSIC: BIRD NOTE® THEME]

BirdNote ® Night Voices

Eastern Whip-poor-will (Laura Gooch)

CURWOOD: The advent of spring brings with it the arrival of migrating birds - and fills our skies and gardens with song. And as Mary McCann reminds us in today's BirdNote®, the cheerful warbling is not confined to daylight.

[CRICKETS CHIRPING]

[BUFF COLLARED NIGHTJAR CALLS]

MCCANN: As darkness descends on a May evening, the voices of many birds go quiet.

But for some birds, especially those known as nightjars, the music is just beginning. In the moonlit shadows of an Eastern hardwood forest, an Eastern Whip-poor-will shouts out its name.

[WHIP-POOR-WILL CALL, REPEATED]

MCCANN: The same evening, in a Southeastern woodland, we hear the loud calls of a Chuck-will’s-widow.

Chuck –will’s widow (Glen Peterson)

[CHUCK-WILL’S-WIDOW CALLS, REPEATED]

Common Poorwill (Ken-ichi Ueda)

MCCANN: West of the Rockies, the voice of a Common Poorwill echoes across a canyon.

[COMMON POORWILL CALLS, REPEATED]

Common Pauraque (Jason Forbes)

MCCANN: Along the Rio Grande River at the southern tip of Texas, a Common Pauraque calls from the thorn scrub.

[COMMON PAURAQUE CALLS, REPEATED]

MCCANN: And, in the desert night on the Arizona-Mexico border, a Buff-collared Nightjar repeats its Spanish nickname, Tucuchillo.

[BUFF-COLLARED NIGHTJAR CALLS, REPEATED]

MCCANN: I’m Mary McCann.

[COMMON POORWILL]

[Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call of the Eastern Whip-poor-will [#84871] W.L. Hershberger; call of the Chuck-will’s-widow [105213], call of the Common Poorwill [40634], call of the Common Pauraque [87464] and call of the Buff-collared Nightjar [40510] all recorded by G.A. Keller. Single cricket by Nigel Tucker.

Crickets [Essentials 64] recorded by Gordon Hempton of QuietPlanet.com.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org May 2013 Narrator: Mary McCann]

CURWOOD: To see some photos of these merry wanderers of the night, swoop on down to our website LOE.org. Coming up...Wild weather and whales. Stay tuned for more of Living on Earth.

Related link:

Bird Note

[MUSIC: Donald Fagen “The Nightfly” from The Nightfly (Warner Bros. 1982)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nicky Hopkins: “Edward” from The Tin Man Was A Dreamer (Sony Music 1972)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendida Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

The Wild Weather Book

From up here we can see our wind chime really well. (Naomi Arenberg)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

“Imagine jumping in the biggest puddle you can find, or playing barefoot and feeling squidgy mud ooze up between your toes. How about letting the wind push you along? There’s no need to stay cooped up when it’s wet, windy or cold…”

That’s the introduction to The Wild Weather Book: Loads Of Things To Do Outdoors In Rain, Wind and Snow. It’s a sort of recipe book by Fiona Danks and Jo Schofield describing activities that require little more than the right weather and a child’s imagination. Recently a teacher in southeastern Massachusetts got his after-school contingent ‘cooking’ with some ideas from the book - and Naomi Arenberg put on her waders to go check it out as well.

ARENBERG: School is out at Friends Academy in Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Cross-legged on the library floor, it’s me and five kids.

ZEKE: Zeke.

KAZIMIR: Kazamir.

OSTA: Osta.

CHLOE: Chloe, .

FRANKIE: Frankie.

ZINE: And Mr. Zine.

ARENBERG: That’s Peter Zine, the teacher in charge of these first- and second-graders.

ZINE: And so, guys, today we’re gonna be using this book. It’s called “The Wild Weather Book: Loads of Things To Do Outdoors In the Rain, Wind, and Snow.” What type of wild weather do we have today, do you think?

KID: Wind.

ZINE: Wind, definitely. So we’re gonna do some activities that utilize the wind, that will allow us to build stuff and have some fun outside. So guess what we’re gonna do first. We are going to do an activity, which makes music…with cooking stuff.

(KIDS COMMENT AS ZINE TAKES UTENSILS OUT OF BAG.)

ZINE: So look at this, look at this picture.

ARENBERG: The kids lean in close to examine a photo of children hanging kitchen utensils on a tree in the wind.

ZINE: You guys see that picture? So here’s what we’re going to do. Listen to this. “Raid the kitchen for whisks, wooden spoons, skewers, pan lids and anything else you can find that might make a noise. Try banging them together to see what different sounds you can make, and then choose some to hang along a stick.” So we’re going figure out how to make a wind chime out of all this stuff. Whad’you guys say, we go outside?

Kaz positions the potato masher. (Naomi Arenberg)

KIDS: Yeah

ZINE: Make something?

KIDS: Yeah!

ZINE: All right, bundle up.

ARENBERG: It’s a short walk to the open space behind the school, where there’s an enormous copper beech as well as a few young trees. The children grab spatulas and salad tongs and bang them together to test the sounds, and then look around for the best tree.

ZINE: What tree do you think we should use?

KIDS: That one! That one has really strong branches.

KID: In background: Easy-peezy, lemon-squeezy.

ZINE: How are we gonna do this? Does anyone have a plan?

KID: I do!

ARENBERG: The boys explain their construction schemes, but a couple of the girls are experimenting with their pizza cutters and kitchen shears.

KIDS: I’ll help clip the grass. She’s clipping the grass.

ZINE: These tools do more than just kitchen work, huh? We could landscape.

KIDS: She’s cutting the grass. I’m clipping it.

ARENBERG: They trim the lawn for a bit, then return to their chosen tree. Soon these six and seven-year-olds are lacing string through the holes on spatula handles, tying knots, and arranging their music makers on a low branch.

ZINE: Very cool, Frankie!

ARENBERG: Oh, wow, you’ve got three on there!

ARENBERG: And the kids find even more uses for the utensils. A pair of tongs with a hole at the top can turn into a telescope.

With a little imagination tongs can turn into a telescope. (Naomi Arenberg)

ARENBERG: (LAUGHS) I need a photo of you doing that. Can one of you look through there?

ZINE: Yeah, why don’t you hold it up? Hey, guys, why don’t you come down and see what’s going on over here?

KID: I can see from up here.

ZINE: You have a good vantage point there, Frankie?

KID: Yup.

KID: Wow, that looks pretty nice.

ARENBERG: So, which utensils are hitting each other and making noises?

KIDS: OK, so this is a potato masher. Pizza cutter. Spatulas. Whatever this thing is. I don’t know. Maybe a salad scooper or something?

ARENBERG: Good for you!

KID: The pizza cutter is also something that Osta uses to cut grass…Check out this bug I found.

ZINE: Girls, come over here for a minute and let’s see if we can hear our wind chime.

KID: There’s not much…(CHIMES GO CRAZY.)…A little too much…

ZINE: I think this is a pretty cool wind chime. What do you think?

KIDS: Yeah…yeah…yeah…yeah…

ARENBERG: With the wind chime finished some of the kids wander off to the lawn.

KIDS: It’s sprouting! Soon we’ll have our very own maple tree right here. Yay!

ARENBERG: Did you guys plant that or did you find it?

KIDS: We just found it!! (CHIMES CLANGING.) It has to grow big and fat, so…(CHIMES CLANGING)…

ARENBERG: Maybe someday you guys will come back when the tree is big enough for you to build a wind chime on it.

KIDS: Yay! - Hey, hey, don’t pick it! - I’m not! - And don’t put a leaf on it.

ARENBERG: As Peter Zine is packing up his string, the kids hum along with their wind chime.

ZINE: He’s trying to make the same sound as the wind chime. Do you want to try it out?

KID: OK.

(GENTLE HUMMING, THEN BURSTS OF LAUGHTER.)

KID: Frankie!

KID: I’m not good at making sounds.

(MORE LAUGHTER.)

ZINE: Aw’right, guys, say “bye” to your windchime.

KIDS: Bye, windchime. Bye, little plant…

ZINE: Say ’bye to your little tree friend. And I want to show you something very cool, and then we’ll try to think about how we can make boats.

ARENBERG: We head down a grassy slope, toward the trees and a vernal pool. As soon as we’re in the woods, the kids notice a strange sound.

We sailed our boats in this vernal pool. (Naomi Arenberg)

(DISTANT WOOD FROGS CROAKING)

KID: What’s that…?

ZINE: What’s that sound?

KID: It’s creeper…ribbet, ribbet, ribbet, ribbet, ribbet, ribbet…

ZINE: Wood frogs… Sound like ducks, don’t they?

KID: Sound like ducks.

ZINE: So, if you guys want to wait here, I’m gonna go in the, I’m gonna go in and grab some for ya’.

ARENBERG: Peter Zine wades into the water and collects some wood-frog eggs in a plastic tub.

Everyone got to pick up the wood-frog eggs. (Naomi Arenberg)

(SOUNDS OF SPLASHING)

KIDS: I, I knew it! Can I touch it? Eeee-ooo. Ugh!

ZINE: What does it feel like?

KIDS: They feel like jello. (LAUGH). They feel gross! Tadpoles growing inside ‘em. Oooch. Don’t pop ’em! Do not pop ’em!

ZINE, Frankie, wanna try and pick it up, Frankie?

FRANKIE: Ok

ZINE: Whad’ya think?

FRANKIE: Cool.

ZINE: Don’t break ’em up…There we go, we’ll keep ’em together…You wanna say ’bye to the frogs?

KID: ’Bye, little frogs.

ARENBERG: The kids find everything interesting – frog spawn, fox tracks, fallen trees. It’s not clear whether they’ll focus on making boats out of twigs and leaves, the way those smiling children in the book did, but their teacher sounds confident.

ZINE: So, we’re gonna try to make a boat. What do you think we can use? Because we don’t have materials for this one. I didn’t get anything. Zeke, what’s your idea? Zeke is raising his hand. We’re gonna ask Zeke what he thinks.

ZEKE: This could be like the sail. It could go like this. To make the boat go.

ZINE: Excellent. So let’s, let’s gather some materials for making a boat. Use your imaginations.

ARENBERG: The five boat-makers set off, eyes trained on the ground, skirting the pool’s edge.

(CHATTER –“IT IS SORT OF DEEP…BUT I’LL GO THROUGH…YOU NEED SOME STRING?”)

KAZIMIR: My feet are way under this mucky water, and I’m looking for like a good leaf…

ZINE: Hey, Kaz, Zeke has an idea, but he would like some help tying. Do you think you could help him out? (SPLASHING.)

Tying pine needles to twigs takes two pairs of hands. (Naomi Arenberg)

ARENBERG: There’s plenty of string. Still, it’s tricky to figure out how to tie leaves or pine needles onto twigs or bark.

KID: This is hard.

ZINE: Maybe get down low…

KID: Could you help us?

ZINE I would love to help you. Yeah.

KID: I’ll go back into the water.

KID: I don’t care if I get my jeans messy.

KID: This does not float, though.

ZINE: (CHUCKLES.) How come?

ARENBERG: And even if the boats float, you could face other problems.

ZEKE: But then how could we try it out when there’s like so deep water?

ZINE: That’s a good question. What do you think we’ll do?

KID: And how do you do it, like, to pull it back?

ZINE: Ah, that’s a really good question.

KID: You could use a string…attach a string to it...yuh, yuh, yuh…then you could pull it back.

ZINE: Hey, Kaz, let’s try not to get too much water IN your boots. OK, bud? Try not to poke anybody in the eye with that.

ARENBERG: Despite the challenges, all the kids have gathered leaves, twigs, moss, pine needles, bark, maybe a bit of mud, and designed a very small watercraft.

KID: I have a very thin piece of wood for the bottom. I have a holly leaf for the sail, and I have tuh- three twigs for the edges.

KID: Don’t tie my finger on!

ZINE: No. (Chuckles)

KID: I hope my boat works!

KID: This is hard.

KID: It floats! Now, that is a good boat…OK, (GRUNT) …Grab it back out of the water…I don’t think we’ll need those…Some sticks are falling off.

ARENBERG: And with that successful launch, it’s time to gather up all of the boats, the string, the wild weather book, assorted coats and hats, and trek back up the hill to the school building. I hope that everyone had a good time, but it’s hard to tell. Then Kaz speaks up.

KID: That was really fun. Are we gonna do any more?

ARENBERG: I would, but I think your parents might be here to pick you up. What was your favorite part of what we did outdoors, of all the things we did outdoors?

KID1: Touch the frog spawn.

KID2: Mmm…I liked everything.

ARENBERG: As for Peter Zine, the teacher…

ZINE: Anything that encourages youth to get outside…I love that, that message that the book sends, that just because it’s wet outside or windy, that we don’t have to retreat indoors, that, you know, there’s still a lot of fun things to do outside.

ARENBERG: I love the way they were showing off their boats.

ZINE: (CHUCKLES.) Yeah, they were quite proud. They didn’t need to be too complicated. The smallest ideas, used big in imagination, so the kids had a lot of fun creating those boats. Yeah.

ARENBERG: And maybe that’s the essential message of a book like this – that any activity can launch kids’ imagination, creativity, and discoveries. And perhaps a maple sapling will sprout up behind Friends’ Academy, where Chloe, Frankie, Kaz, Osta, and Zeke were the first to notice it.

For Living on Earth, I’m Naomi Arenberg in Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Authors of The Wild Weather Book have a website, designed to interest children and families in exploring the outdoors

- You’ll find more information about The Wild Weather Book: Loads Of Things To Do Outdoors in Rain, Wind and Snow, by Fiona Danks and Jo Schofield, at the publisher’s website

[MUSIC: Herbie Hancock “4AM” from Mr. Hands (Columbia Records 1980)]

Right Whale in the Wrong Place Update

Wart and her baby in April, still swimming strong. (Marilyn Marx/ New England Aquarium)

CURWOOD: Back in January we reported on the right whale in the wrong place. In the winter, Northern Right whales typically give birth in the warm waters of Florida and Georgia. But this winter a whale named Wart had a calf in the chilly waters of Cape Cod Bay - the first time in 27 years of data collection that scientists had ever seen a baby Right whale that far north in the winter. And scientists at the New England Aquarium and Whale and Dolphin Conservation were very concerned that the baby might not survive. Regina Asmutis-Silvia is senior biologist at Whale and Dolphin Conservation in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and we called her to get an update on the wayward whales. Regina, welcome to Living on Earth!

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, I’m on the edge of my seat here! What happened to Wart and her baby?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Well. I am very, very happy to tell you Wart and her baby are doing well. The aquarium reported a sighting of them on April 18. So the calf was about three months old and it looked really healthy, it looked fat. Mom was feeding so it’s a really good sign that at least while they face other threats, she’s over the hump, I think mom is...Wart is with caring for this calf and having had it in colder waters. And so it looks very, very positive.

CURWOOD: So by April 18, the calf is good to go in terms of surviving the northern winter.

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: I hope so, yes, I mean, I think that at three months old and seeing that the calf looked healthy and getting confirmation that it's still with mom and feeding - it’s very, very hopeful. There's always issues with all Right whales and all calves, particularly moms and calves, because they spend so much time at the surface, that ship strikes continue to be a concern, entanglements continue to be a concern for this species in general. But I think our concerns are a little bit elevated about the fact that it was born here [at this time of year] - that's not the problem now. It’s the problem that the population and species face in general that we’ll remain concerned about for all them.

CURWOOD: By the way, is this boy whale? Girl whale?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: We don't know. You can't really tell by looking at them. You can do it genetically if you get a skin sample. You can do DNA testing or if they roll over, their genital slits are on the underside of the tail stalk, and there’s little slits that the moms have that are mammary slits from where the calves nurse from that are absent from the males. So unless they roll over and we get a good look at the underside of the tale stalk, you can't tell. Or obviously if you see an adult whale mom with a calf, you’ll always know Wart’s a female because she’s had calves so it's not an easy thing to visually do.

CURWOOD: How much milk does a mother Right whale give in a day to its baby?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: The calf will drink about 40-60 gallons of milk a day, and it’s a really rich and fatty milk so while it might not seem appetizing to picture or want to consume, it's kind of...thinking like a mixture of sour cream and cottage cheese and yogurt together. And it's very rich and fatty like that.

CURWOOD: So now it’s the middle of May, and I'm wondering if Wart and her baby have been joined by the rest of the Right whales ordinarily around?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: We did have in April a huge amount of Right whales in Cape Cod Bay, unusually on the west side of the bay - it’s not where we typically see them. Most of them have left the bay now, and we think that what they usually do is leave the bay in mid-May - end of April, mid-May - and they head out east of Cape Cod to the Great South Channel. That’s what we think they do, but I think as Wart and her calf surprised us here, there’s always potential surprises of how things are going to change. Now I think we’re all waiting to see where they’re going to show up.

CURWOOD: Now you say you saw the whales on the west side of the Cape Cod Bay - of the arm of the Cape - what does that do for them in terms of being in marine protected area?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: It's a big concern for us because the west side of Cape Cod Bay is not protected - just the middle and east side is. In part, that’s because historic sitings have shown that they prefer to feed in the late winter, early spring. But we had not only Wart and her calf on the west side, we have probably third of the Right whale population that was on the west side of the bay at the end of April and beginning of May, and the food was very thick. I actually got a call from a harbormaster in Duxbury who told me they thought they had a Pilot whale stranded in 10 feet of water. And I went down to check it out and it was a Right whale skim feeding probably 100 yards off the beach just going back and forth - very unusual to be able to stand on a beach - the west side of the bay - and watch these animals. And we probably had at one point maybe 130 Right whales between the Cape Cod canal and Green Harbor, which is a little bit north of Plymouth. So I think that that's just really important for the government agencies to recognize that these animals do use the west side of the bay, and that area does need to be protected.

CURWOOD: So if the animals with there, then whatever they eat must be there.

Wart and her baby shortly after it was born. (Allison Henry)

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Yes, they’re feeding on tiny little crustaceans that are zooplankton - they’re tiny microscopic animals called copepods. And the copepods were very, very thick on the west side of the bay. We don't know how they find their food - we have no idea. Clearly, they're good at it, and they basically graze it out. And they spend as much time feeding on it as they could to a point where they had diminished the copepod population. And they take off for - in this case it’s not greener pastures, the copepods are red, so they’re looking out for redder pastures in parts of the ocean now.

CURWOOD: Where will they feed come summer do you think?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Usually they go from the Great South channel in early summer and then mid-to-late summer to early fall they’ll head out to Bay of Fundy in Canada and around northern Maine, going up into Canada. And again, I say usually because nothing has been usual about this year, so we're just going to kind of watch and see what happens.

CURWOOD: When we talked to you last it was too early for Wart’s baby to have a name, he hadn't yet developed the markings some scientists use to identify a whale, but has that changed anyway?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: No, officially that calf won’t get named for probably for a year or so. Unofficially we’ve all come up with all kinds of nicknames, but no official name yet.

CURWOOD: What’s your favorite one?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: One of the ones we were definitely kicking around, just because Wart’s the mom, is Blister. So we’ve got Wart and Blister. You know, we don't have any real official name and we’re just, name’s aside we don't...aren’t worried about the names so much as we are worried about the well-being of animals. So we're looking forward to the calf actually getting to be a year or two old so it can officially be named because that obviously will be a great celebration itself.

CURWOOD: Regina Asmutis-Silvia is a senior biologist at Whale and Dolphin Conservation. Thank you so much.

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: And next time you see Wart, give her a hug for me, would you?

ASMUTIS-SILVIA: Absolutely!

Related links:

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation

- New England Aquarium’s Biography of Wart

[MUSIC: Electric Light Orchestra “The Whale” from Out Of The Blue (Sony Music 1972)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show, and we're glad to welcome our new intern Poncie Rutsch aboard this week. We also have a special thanks to Ari Daniel Shapiro and Mind Open Media, with support from the BP/The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth