April 17, 2015

Air Date: April 17, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Guardian Newspaper Climate Campaign

View the page for this story

Before he retires this year, the Guardian Editor in Chief Alan Rusbridger wants this UK paper with a readership of more than 7 million to focus forcefully on climate change. Not only will the journalists cover from every angle, Rusbridger explains to host Steve Curwood the paper will advocate for climate activism, as this is the most vital story in the world and arguably the hardest of our time to convey. (14:00)

First Warnings of Endocrine Disruptors

View the page for this story

Common synthetic chemicals that surround us and are in countless products can get into the human body and affect the immune system, intelligence and the reproductive system. In 1994, host Steve Curwood followed the investigative trail of these endocrine disruptors, and spoke with Theodora (Theo) Colborn, one of the first scientists to sound the alarm about the effects these chemicals can have on organisms and the environment. (04:00)

The Mother of Endocrine Disruption Science

View the page for this story

Theo Colborn may have waited until her 50s to get her PhD, but she still became a trailblazer in the field of environmental health. Theo died last December, and in this season of Earth Day fellow scientist and collaborator Laura Vandenberg and host Steve Curwood remember Theo's life and discuss her contributions to scientific knowledge. (09:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra discuss the prevalence of asthma among Olympic-level swimmers and look back on Richard Nixon’s environmental record and the 45 years since the first Earth Day. (04:45)

Springtime Birding with David Sibley

View the page for this story

As they head north, migratory birds search out pit-stops on their trip, and local birds are eager to breed. Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts is perfect for both, and a good place for host Steve Curwood to meet up with David Sibley. They listen to birds and discuss the second edition of Sibley’s popular and erudite Guide to Birds. (14:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alan Rusbridger, Theo Colborn, Laura Vandenberg, Peter Sibley

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The Guardian newspaper in the UK mounts a full-court press to report the urgency and need for action on global warming – a story journalism hasn’t told well.

RUSBRIDGER: Journalism I think of it as a rear view mirror. Journalism works well with things that have happened that you can describe. It works less well with things that might happen, or things that move very slowly.

CURWOOD: Also, an Earth Day remembrance of scientist Theo Colborn, a pioneer who raised the alarm about endocrine disrupting chemicals.

VANDENBERG: I was extremely privileged to work with someone like Theo; I also really looked up to her for doing work in a field that was so controversial. She really took a stand for the sake of planet earth and human health.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

The Guardian Newspaper Climate Campaign

Alan Rusbridger (bottom right) and his staff at the Guardian discuss their “Keep it in the Ground” campaign. (Photo: The Guardian)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Alan Rusbridger has been the chief editor of the respected UK paper the Guardian since 1995, and last December as he considered his retirement at the end of 2015 he had a chance encounter with Bill McKibben. Bill McKibben, as you may have heard in our broadcast last week, is a writer who has also become a leading activist confronting society about climate change and the fossil fuel industry. In the 20 years that Alan Rusbridger has led the Guardian, the paper has established an impressive reputation for environmental coverage, but that meeting inspired Alan to dedicate his remaining time as top editor to covering and campaigning for the climate. So along with reporting on climate change the Guardian is sponsoring a petition that calls two of world’s richest foundations, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust to divest their holdings in fossil fuels and that petition already has over 100,000 signatures. Alan joins us now on the line from London. Welcome to Living on Earth.

RUSBRIDGER: I’m pleased to be here.

CURWOOD: So, to start with, I understand that Bill McKibben is the one who maybe sparked the idea to devote your final year as editor to covering climate change. How did that happen?

RUSBRIDGER: Well, we both won an award in Sweden at the end of last year, and over lunch I was talking to him about his passion, which is the environment, and I said that I felt that we've never really quite cut through. We've got five environment correspondents so it's not like we haven't done justice to the subject, but I thought we were victim to the fact that people switch off I think when they read about the environment, it seems too dismal, too complicated, there's nothing they can do about it, and Bill told me about his campaign and the fact that the divestment movement in his mind was snowballing, was having the kind of cut through that traditional journalism wasn't happening, and that gave me the idea of combining the reporting with the campaigning to try and jolt people out of the complacency that I think they feel.

CURWOOD: Why do you think that journalists have struggled to tell the climate change story?

RUSBRIDGER: Well, I've been thinking about that and I think journalism, I think of it as a rearview mirror, that journalism works well with things that have happened that you can describe. It works less well with things that might happen, or things that move very slowly. So it's very difficult to describe the gentle melting of an iceberg or the change in the atmosphere, it's very difficult to definitely ascribe climate events - hurricanes, tornadoes, and rains - to climate change so journalism just struggles to describe what's going on and because nothing very dramatic happens from day to day, it slips off the front pages. I think readers have stopped reading about it because it feels in a way too frightening. I think psychologists have written entire books about this, and so somehow this story, which I think of as probably the most important story on Earth, is not being told by journalists.

The Guardian is launching a campaign to encourage people and organizations to keep the carbon in the ground and not to drill for fossil fuels. (Photo: The Guardian)

CURWOOD: I have to tell you that on a personal level more than 20 years ago I came to the conclusion that human-induced climate change is the most important story of the day, started this program Living on Earth on public radio in the states and have been telling the story and I have to say it's very hard to keep the enthusiasm going on this story. How do you plan to tell the story differently to engage people?

RUSBRIDGER: Well, I've been editing for about 20 years, and I've been quite reluctant to do big campaigns because I think campaigns only really work to my mind where you've got something about which there is no reasonable doubt, and I there are not many stories which fall into that category. I think where there is reasonable doubt it's better to do reporting because then you report all sides of the argument. With climate change, I think most people, most reasonable people, accept that the science is pretty settled. There's something like a nine to one majority for scientists who think the same about the nature the risk and its causes, and so I think where you've got that I don't think there's any great obligation to bend over backwards to be balanced, and having decided that then I thought let's turn this into a campaign that involves reporting rather than simply reporting which for one reason or another isn't cutting through in the way that it has to. This is an urgent story. We can't afford to spend the next few years waiting for people to wake up to its seriousness.

CURWOOD: Now, what was the reaction of your colleagues there at the Guardian when you told them about your idea that you were going to spend these last few months of your leadership of the paper in this campaign on the climate?

RUSBRIDGER: I can't remember ever having such universal enthusiasm. What I did over Christmas was to e-mail a large number of people, not actually just in editorial but across the organization to say, look, we were thinking of doing this and who wanted to be involved, and about 45 people turned out to the first meeting. And I think what you realize is that it's not that people aren't interested, it's just that they can't find the vehicle to engage. And so once you say look we're going to do this and we want to harness the abilities of as many people as possible, there's tremendous enthusiasm because we're all people as well as reporters and workers here. We've all either got young relatives or children or grandchildren. People are on some level deeply engaged in this existential threat that could put all that in jeopardy. So, actually, there's been a fantastic internal and external response.

CURWOOD: Now as I understand it, The Guardian is launching what you're calling the "Keep it in the ground" campaign. Tell me about it.

RUSBRIDGER: Well I think there's one very simple way of looking at this, and this is Bill McKibben's way of framing it, which is if you concentrate just on three facts, one is that we have to stay within two degrees of warming - and I think there's a universal consensus about that - even amongst people who disagree about how to do that. Civilization as we know it will begin to become very difficult to maintain about two degrees. The second fact is the amount of fossil fuels that people own and is in the ground, and the third fact is the amount of fossil fuels that can safely be burned to stay within two degrees. The amount of known reserves of fossil fuels is vastly greater, about four or five times greater, than the amount that can be safely burned, and so, therefore, it is not safe to dig up all the oil and the gas and coal that we know about, and once you agree on that, then you look at the companies and you say these companies cannot be valued right. They're putting all this stuff in their books, in fact, they're searching for more and yet they're never going to be allowed to use it for the sake of the species, and, therefore, it has to be kept in the ground.

CURWOOD: Well, there's one rather pressing factor though. If you think of the end of slavery, perhaps as an analogy to the campaign here about, the value of a slave for example in United States back in the day was equivalent to say a luxury car. If you tell these companies that they have to keep it in the ground they have billions upon billions of dollars predicated on that. They're not to go willingly are they?

RUSBRIDGER: No, they're not, and therefore you look at the levers that are going to change that, and there are two levers. Either some form or governmental regulation or rationing or pricing, and the second is the financial levers of people realizing that this is in a very real sense a carbon bubble. These are assets that are going to be stranded and that if you're a wise financial manager you want to get out of that before that bubble bursts. There's not much a newspaper can do about the first bit. Of course, we can lobby governments to bring in the regulations and the limits, and we look to Paris for that to happen in December, but we thought that's not going to be very engaging for readers - that feels like political wonkery. But the idea of trying to go for divestment, trying to persuade people all of the risk to their investments and for them either on moral grounds or probably more likely on their pure financial self-interest grounds to get that money out of fossil fuels before that bubble bursts. And again we're not naïve enough to think that if we rang up Shell or BP or Exxon and suggested that they keep the stuff in the ground that that was going to have much effect. But I think that all organizations like the Gates Foundation like the Wellcome Trust in the Britain which are devoted to science and medicine who are progressive in every way in terms of all of the good that they do to humanity and just say look, don't you think that you should be taking the lead in terms of not having money in these things which we know cause damage to the planet and to health.

The Guardian wants to put pressure on some of the world’s largest charities to pull their investments from fossil fuel companies. (Photo: Marianne Muegenberg Cothern, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And it's kind of interesting that when you realized that your own portfolio at the Guardian had plenty of fossil fuel holdings, so what did you decide to do about that?

RUSBRIDGER: We were aware that the moment we started writing this, people would point the finger back at us. The Guardian is a company that is run by a trust. It's a not-for-profit company is the simplest way of thinking about it and we have about $8 billion dollars invested and we realized, well, people would say well it's all very well to wag your fingers at others, but what are you going to do yourselves? And I went to the GMG board, the Guardian Media Group board, and said, look this is an issue you don't have to be bound by The Guardian's reporting or campaigning but on the other hand people are going to draw attention to what you do, and actually the board went away and thought about it, board is very hard-nosed businesspeople so they weren't making a wooly-minded choice, but I think they hadn't concentrated on the issue before the moment they did they realized the sense in divesting and they came out last week and said they would be it divesting over a period two to five years from fossil fuels. So that was a commencing charging something that's the biggest fund so far that has divested.

CURWOOD: How will you measure the success of this campaign? You've decided that it's appropriate now to begin advocating up taking a position rather than just reporting on the news makes you a campaigning as well as a news organization. How will you measure the success of this decision and this campaign?

RUSBRIDGER: Well, to some extent I think we've succeeded in galvanizing an awful lot of people to sign with us. When I last looked at the petition, it had been signed by 170,000 people. The people who are running the Paris talks have been in touch saying this is a fantastically helpful thing in terms of getting it on the radar of politicians and the people who are going to be negotiating those talks. I think the fact that the Guardian Media Group has divested will make fund managers sit up and realize that there is an issue here they need to concentrate on. So I think we had a quite remarkable success already and obviously we're going to keep up our reporting, our campaigning, and I expect us to draw attention in a very stark way to the contradiction between these as I say admirable foundations, Gate's and Wellcome, who do so much good, but I think really shouldn't be having their money in things that have the potential to do unimaginable harm.

CURWOOD: Looking again at, say, if the analogy of ending slavery the kind of political and social movement that had huge economic implications in the United States that wound up in the Civil War, really bloody war. In the UK, you folks divested of slaves in fits and starts but there was not the kind of conflict. What's the difference there and how might that lesson be applied today?

Alan Rusbridger, Editor and Chief of The Guardian (Photo: International Journalism Festival; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

RUSBRIDGER: Well I didn't know whether this is so much Britain versus the US. This is probably the biggest imaginable global threat and I think crosses all cultural national political boundaries and it's only going to be solved by and international will. You make analogy with slavery; other people are making an analogy with tobacco, or with apartheid South Africa. I think there's other kinds of moral comparisons, but I think in the end whether or not there is immediate political will I think this thing will be determined by people who realize that those three figures that we talked about earlier have a kind of logic of their own, and no one wants to be the person holding onto the pass the parcel when the bubble bursts so I would anticipate that the more you can get this into the heads of the people who have their money there, and it's not like these assets have been performing that well anyway there will be a flight from fossil fuels, and once you get to that tipping point then the whole economics of renewables versus fossil fuels changes and I think things could begin to change quite quickly.

CURWOOD: Alan Rusbridger is editor of the Guardian. Thanks so much.

RUSBRIDGER: Thank you, I enjoyed that.

Related links:

- More about The Guardian’s climate campaign here

- Their petition asking The Gates foundation and the Wellcome Trust to divest from fossil fuels

- Listen to the podcast “The Biggest Story in the World,” which takes you behind the scenes of the Guardian’s campaign

[MUSIC: Gary Demichele, Angular Dissent, Big Night Music from the Motion Picture, Megaphonic, 1997]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the remarkable life and legacy of science pioneer Theo Colborn. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dick Hyman Group, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles. Sweet and Lowdown]

First Warnings of Endocrine Disruptors

Theo Colborn, one of the first scientists to warn the public about the dangers of endocrine disrupting chemicals. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons; CC BY SA-4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Many scientists believe global warming is the greatest threat facing the planet, but it’s hardly the only threat in our environment. Other dangers include the many powerful chemicals now found everywhere in our earth and water, and in this season of the 45th Earth Day we’re taking the opportunity to remember one of the most innovative environmental scientists of recent times, Theodora Colborn. It was Theo who first correlated the data suggesting that tiny doses of many common chemicals such as plasticizers and pesticides could mimic hormones in humans and wildlife, with effects that might include depressed sperm counts, and a heightened incidence of the painful condition, endometriosis. In 1994, Theo Colborn, then a senior scientist at the World Wildlife Fund, explained her ideas on Living on Earth.

COLBORN: I think we have flooded the environment with a large number of chemicals that look like or interfere with hormones, neurotransmitters, growth factors, and inhibiting substances.

CURWOOD: Dr. Colborn calls these chemicals endocrine disrupters. The endocrine system is the delicate network of glands which produce hormones: the powerful chemical messengers which regulate our most vital biological processes, including sexual development, immune response, and the way we react to stress. Natural hormones are intensely powerful, but quickly eliminated by our bodies. Synthetic chemicals which act like hormones, on the other hand, are much weaker, but our bodies don't know how to get rid of them, and they build up, mostly in our fat. Dr. Colborn worries that the most important impact of these substances may not be on the people directly exposed to them, but on the next generation: on their offspring. In pregnant women, Dr. Colborn says, hormone-imitating chemicals can leech out of fat cells, cross through the placenta, and wreak havoc on the fetus at the most vulnerable stages of development.

COLBORN: They look like hormones, and they are capable of getting into the body and interfering with the normal hormonal activity, and the messages, the normal messages, that control normal growth.

CURWOOD: Many of the chemicals that Dr. Colborn suspects are endocrine disrupters are tested for their ability to cause cancer and birth defects, but they are not tested for what she says may be their less obvious, but no less devastating impact.

COLBORN: We had been focusing on cancer and mutations. We've been sidetracked by that, and we've missed this other, really more insidious effect. If the immune system is affected maybe they're not well all the time. If their nervous system is affected, maybe they're not as smart as they should be. Maybe they have problems with behavior. Maybe we're affecting their fertility, so that population may not be able to reproduce eventually.

CURWOOD: And these chemicals are all around us now. All the time.

COLBORN: That's right. That's right. Steve, you're sitting there right now with at least 500 measurable chemicals in your body that were not there before 1940. And I think what's happening is that you can't predict what these chemicals are going to do.

CURWOOD: Some of the substances that Dr. Colborn suspects are endocrine disrupters are heavy metals. Cadmium, lead, and mercury. But most come from a class of chemicals called organochlorines. They are used in thousands of products from pesticides and plastics to pharmaceuticals. DDT and PCBs are organochlorines that were banned because scientists believe they cause cancer. But even that link is uncertain. In fact, so little is known about so many of these chemicals that critics charge Dr. Colborn's theory is just that: a theory and nothing more. But after years of analyzing research from around the world, Dr. Colborn is convinced by what she's seen.

COLBORN: There was a consistency to what I was finding. It's called what I call the weight of evidence approach.

CURWOOD: That’s Theo Colborn, speaking on Living on Earth back in 1994.

Related links:

- Hormone Disruptors Linked To Genital Changes and Sexual Preference

- BPA-Free Does Not Always Mean Safe

- Plastics and Male Reproduction

- The Dose Doesn’t Always Make the Poison

The Mother of Endocrine Disruption Science

Dr. Theo Colborn passed away this winter. (photo: TEDx MidAtlantic; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, now the science of endocrine disruptors is well established, largely thanks to Theo’s pioneering work and the many researchers she collaborated with, efforts that led, for example, to the banning of bisphenol A in baby bottles. Still, regulators have only just begun to address the risks of endocrine disruption. One of very last papers Theo co-authored was a collaboration with a team led by Laura Vandenberg, now an Environmental Health Scientist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Laura joined us for a look back at Theo’s scientific breakthroughs, and what might lie ahead. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Laura.

VANDENBERG: Thank you so much for having me again.

CURWOOD: Tell me, when did you first hear about Theo Colborn?

COLBORN: I think like many young graduate students, I first learned about Theo and her work from her very popular book “Our Stolen Future”. And that was early in my graduate career, and within probably two years of starting my PhD with Ana Soto at Tufts University, Ana, who was close to Theo had introduced us electronically so I could start chatting with Theo about things that I thought were interesting and that she could help me with.

CURWOOD: And may I ask you, how did you feel as a woman scientist having Theo as a mentor in a way for you?

VANDENBERG: I was extremely privileged to work with someone like Theo. I’ve always really admired people who are willing at some point in their life say, you know, I want to do something different.

That takes a lot of bravery and Theo got her PhD in her 50s. That's not the traditional path, that's certainly not been my path and I really looked up to her for that, but I also really looked up to her for not just getting that degree but doing work in a field that was so and is so contentious and controversial. She really took a stand for the sake of planet Earth and human health, at a time that maybe a few other people were and few women were.

CURWOOD: Now it's more than 20 years since the really put her ideas out there. How do these concepts look some 20 years later?

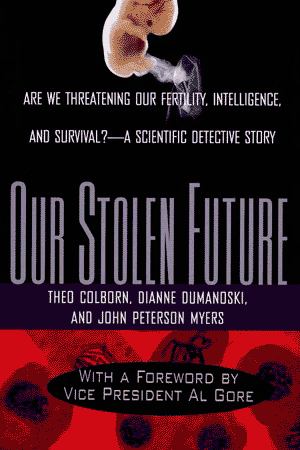

Theo Colborn’s most famous book documents the impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals on our health. (Photo: DES Daughter; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

VANDENBERG: At the time the research was being proposed as a hypothesis, something that was still being tested, something that required more data to really convince even the practitioners in the field that something was going on. It was called the low-dose hypothesis, the idea that low levels of chemicals could affect the health of wildlife and humans. The data is here now. It took 20 years, it took a lot of scientists who contributed, and the evidence is pretty solid that these compounds can affect the health of humans, wildlife, creatures in the laboratory, cells in a dish. We've come leaps and bounds from what was known in the 1990s when Theo started this work to where we are today.

CURWOOD: One of the things that Theo Colborn talked about was the influence that these hormone-mimicking chemicals would have on our reproductive health. What do we know now?

VANDENBERG: There are still trends that are suggesting that reproductive diseases and conditions are increasing, conditions like infertility, endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, cancers of the reproductive tract and breast cancer in humans, and when we go back and look at the knowledge that's been produced in labs with controlled animal studies, we can explain some of these increases in disease from those animals by exposing them under controlled conditions to endocrine disruptors. We can induce a lot of those reproductive diseases that we're seeing increase in human populations. So the connections are there. Can we prove today that any one of those diseases is caused by a single chemical of concern? No, we're not there yet. Is there very strong evidence that the environment is affecting reproduction? Absolutely.

CURWOOD: One of the concerns that Theo Colborn had was regarding our thinking, our brains, our neurological systems. She thought that these hormone mimickers might interrupt the transmission of impulses, that they would affect what are known as neurotransmitters. What do we know about that today?

VANDENBERG: Theo was right on track with this idea and, in fact, neurotransmitters are just one part of what we've been finding with effects of endocrine disrupters. These chemicals are actually affecting the brain as it's being developed. The brain is a really complex organ where you could look at effects on the single cells, like the neurons, you could look at lower levels like the narrow transmitters or you could look at the whole brain anatomy and maybe the more fascinating things about endocrine disrupters is that they can target all of these different levels of biology. Some of the more convincing data showing effects of endocrine disruptors on the brain focus on rodents and regions of the brain that are different in males and females. And creatures that are exposed very early on in life to endocrine disruptors can have brains that don't match their genetic sex. So males that have brains that look a little bit more like female brains and vice versa so I think once again, Theo was right on track and her idea was that the brain was going to be hypersensitive and that it would be very sensitive during early development. In fact, Theo had a quote, "You can't go back and rewire the brain." So if we alter the organization of the brain early on in life, oh boy, we could be in for some real trouble.

Chemicals like BPA in plastics have been found to disrupt endocrine systems. (Photo: Effeietsanders, Wikimedia Commons 3.0)

CURWOOD: As a practical matter, what has Theo Colborn's work meant in terms of various chemicals that we might regulate today?

VANDENBERG: Well, one of the things that Theo helped others in the field to do was to identify just how many chemicals might have endocrine disrupting properties. She helped complied a list of either known endocrine disrupters or possible endocrine disrupters, and the list has more than 1,000 chemicals on it. Theo stayed very active in understanding the latest science about a lot of different chemicals, including BPA, for example. Another thing that is worth pointing out is just in the last few years Theo was one of the scientists that was sounding the alarm about chemicals that are used in hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. And she was pointing out just how many chemicals were used for fracking and how little we knew about them. And Theo was very concerned that these chemicals could also have endocrine disrupting properties in addition to being just toxic.

CURWOOD: When Theo Colborn died in December 2014 she was some 87 years old. So you're telling in her 80s she was working on this?

VANDENBERG: I'm telling you that I think two weeks before she passed, we were on the phone still talking about science. So this was a woman who cared very much about what she was doing, the scientists she was working with, and trying to save the world. I mean, this is a woman who was committed to saving the world.

CURWOOD: So Theo Colborn's ideas have brought you and this part of the scientific community to a certain point. What's next? What's over the horizon? If Theo were today, what direction would she be pointing towards as the need for more research and understanding?

VANDENBERG: I think one of the things that is really on the horizon, and once again, Theo saw it before a lot of us did, was the need to understand how these chemicals act in a mixture. For the most part in the lab, we study one chemical at a time. I treat animals with chemical X and I compare them to animals that weren't exposed. Well, you and I are not exposed to chemical X, we're exposed to chemical A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and we really need to develop the right methods to look at chemical mixtures. Theo's work on chemicals found in fracking is really a question of mixtures, all of these chemicals used together in a slurry. What are they doing?

CURWOOD: How do you think history is going to look back at Theo Colborn's work in, say, another 20 years or more?

Laura Vandenberg (Photo: University of Massachusetts)

VANDENBERG: I think people in my generation of science will look to Theo with awe. Knowing her when she was alive, what she could accomplish, was incredible. But I think the broader lessons that go beyond science to what Theo's legacy will be will also be huge. This is a woman who gave a good part of her life to trying and improving the life of humans, the health of humans, and wildlife. She cared very much for the environment and for how we could protect ourselves from chemicals that we didn't realize when they were first produced could cause such harm. I think that her legacy will only grow from here.

CURWOOD: Laura Vandenberg is Assistant Professor of Environmental Health Science at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Thank you so much for joining us for this Earth Day look back at the life of Theo Colborn.

VANDENBERG: Thank you so much, and thank you for honoring her.

Related links:

- Theo Colborn’s Endocrine Disruptor Exchange

- Laura Vandenberg teaches at UMass

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website or get an audio download. The address is LOE.org. That’s L-O-E.org. There, you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Once again, comments@loe.org. Our post office box is 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line at 800-219-9988, that’s 800-219-9988.

[MUSIC: Ben Fold, Narcolepsy, The Unauthorized Biography of Reinhold Messner. Kranky, 2001]

CURWOOD: Coming up…heading out with the sunrise to hear the dawn chorus. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Noah and the Whale, Instrumental 11, The First Days of Spring, Mercury 2009]

Beyond the Headlines

In the 45 years since the first Earth Day, renewable energy – namely, wind and solar – has taken off, and 79,000 new jobs were created last year in renewables. (Photo: Green Energy Futures, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Earth Day turns 45 years old on April 22, and for a look beyond the headlines back then as well as today, we turn to Peter Dykstra, of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter, what are the stories?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. For the 45th Anniversary of Earth Day, let’s take stock of a few things that are very different between 1970 and today, both good and bad.

CURWOOD: OK, well, let’s start with the good stuff, huh?

DYKSTRA: Back around the time of the first Earth Day, it was still pretty much standard practice for any industrial facility, any sewage system, to dump directly into the air or into the most convenient waterway. Thanks to both laws and public attitudes, the air and water are demonstrably cleaner in the US than they were in 1970. That’s not to say there still aren’t enormous challenges, but amidst all the gloom that tends to dominate environmental discussions, it’s a very good thing and an accomplishment to be proud of. Also, we’ve been talking about this since 1970 and maybe even before, but it looks like wind and solar energy have finally arrived: 79,000 new jobs created in renewables last year.

CURWOOD: That’s a lot of jobs, and some really good news! And, alright, what about the bad news?

DYKSTRA: Well, something else it seems like we’ve been talking about for 45 years: the environmental movement still has an image problem – mostly white, wealthy, and whiney. I think some of this is undeserved, but some of it is. While those 79,000 wind and solar jobs were being created, the coal industry lost 50,000. And that didn’t happen because of the alleged “War on Coal,” it happened largely due to market forces. But it’s still absurdly easy to use environmental concern as a job-killing divisive issue in small town America, in the media, and especially in Congress. After 45 Earth Days, it seems we’ve still got some growing up to do.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey, what do you have for us next?

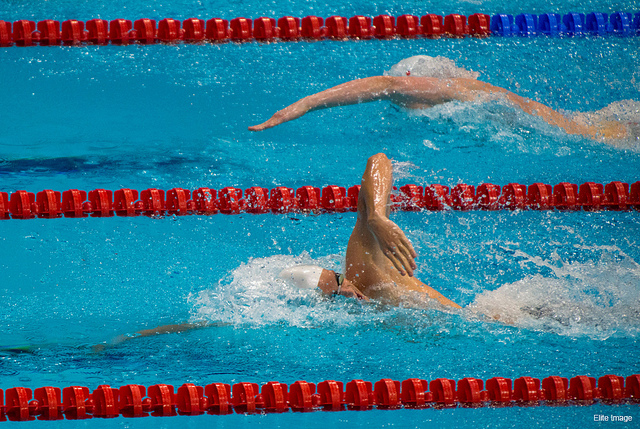

DYKSTRA: Something really counter-intuitive. One would think that top-level competitive swimmers are among the healthiest people around, but there’s a catch. Research from Canada’s McMaster University reports that Olympic-level swimmers are also frequently asthma sufferers.

New research shows that Olympic-level swimmers are frequently asthma sufferers. Scientists speculate that pool chemicals like chlorine contribute to asthma prevalence by irritating the lungs. (Photo: Atos International, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Huh? So, uh, what causes this, is there a smoking gun?

DYKSTRA: Yes, usually at the beginning of every race, but that’s not important now. There’s no absolute proof, but strong speculation that it’s lung irritation from pool chemicals, particularly chlorine. Interestingly enough, the research showed that swimmers, who spend hours of training each day with their nostrils at water level, are most at risk than athletes in other water sports like diving or water polo. In high-level competition, this creates a new difficulty, since chemical inhalers are normally outlawed in elite competition, and the swimmers need to get special permission to use them. But wait!! There’s more.

CURWOOD: OK.

DYKSTRA: Let’s say you’re not a world-class competitive swimmer.

CURWOOD: I think we can both say that.

DYKSTRA: Agreed. In 2006, the European Respiratory Journal published a study of widespread interest for those who admit to, at some point in their lives, having peed in the swimming pool.

CURWOOD: But not me.

DYKSTRA: I totally believe you, Steve Curwood. Me neither. The study said that chemicals in pee can react with pool chlorine and form chloramine compounds similar to the building blocks in some banned chemical weapons.

CURWOOD: So if you pee in the pool, it’s a war crime?

DYKSTRA: Well, not quite, you’d need a whole lot of chlorine and a lot of human contributors as well. But the study said it’s a potential cause of minor lung irritation for pool workers and those exposed to the mix for long hours.

CURWOOD: And I guess it’s a concern for any of us who ever swam in a public pool. Hey Peter, what did you bring to us from the history calendar this Earth Day?

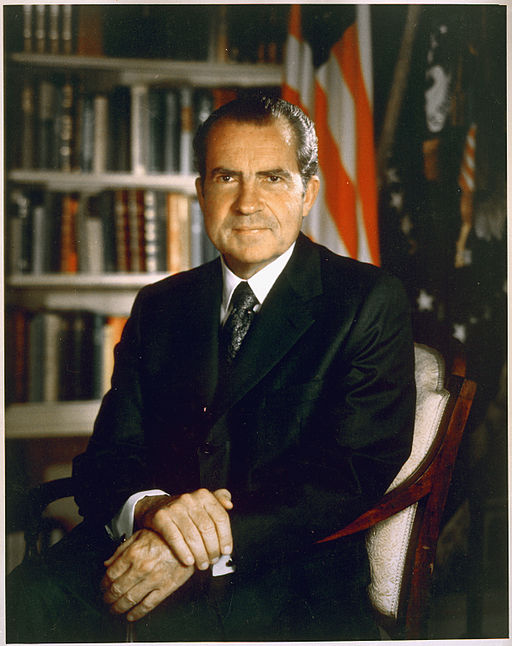

DYKSTRA: Well, appropriately, I’ve got another Earth Day link. The modern President responsible for many key environmental laws and the creation of the EPA died on Earth Day back in 1994: Richard Milhous Nixon. He tends to be remembered for some other things, but Nixon signed legislation creating the EPA, and during his Presidency the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the National Environmental Policy Act – that’s the one requiring impact statements for big projects -- and the outlawing of DDT all happened.

CURWOOD: But wasn’t all of that more of a political strategy than it was Dick Nixon the Tree Hugger?

Richard Nixon authorized the creation of EPA and signed in many new environmental policies, making the 36th President of the United States’ environmental record noteworthy. However, Nixon saw the environment as a political strategy: a way to win back the support of Americans who had been alienated by the Vietnam War. (Photo: Christoph Braun, Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: Absolutely. He saw the environment as a way to make nice with many of the same Americans who had been alienated by the Vietnam War. In private, but with the infamous Nixon tape recorder rolling during a meeting with U.S. auto executives, he said environmentalists wanted everyone “to live like a bunch of damned animals.” Also, Nixon actually vetoed the Clean Water Act, but back in those golden days when there was strong environmental sentiment on both sides of the aisle, Congress overrode that veto and the Clean Water Act became law.

CURWOOD: So even today we reap the benefits of the Milhous Effect.

DYKSTRA: Yikes . . .

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News – that's EHN.org and DailyClimate. org. Happy Earth Day, Peter. Talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: Happy Earth Day, Steve, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- “Coal Loses Nearly 50,000 Jobs, Wind and Solar Add 79,000”

- “Asthma very common among Olympic-level swimmers”

- Journal article: “Exposure to trichloramine and respiratory symptoms in indoor swimming pool workers”

- Essay: “A green Nixon doesn’t wash”

[MUSIC: Dykstra: Sun Ra “lights On A Satellite” from Out There A Minute (Restless Records 1989)]

Springtime Birding with David Sibley

David Sibley’s hand painted portrait of a Mute Swan and cygnets. (Photo: ©David Sibley)

CURWOOD: At five o’clock on a May morning of 2014 , we headed out to the Great Meadows National Wildlife refuge in Concord, Massachusetts, to meet up with David Sibley, author of Sibley’s Guide to Birds” a widely popular and widely used bird guide.

These marshes, lakes and woodlands are pit stops for migrating birds heading north and home for local birds looking to find a mate, and as sunlight starts to flood the sky, the birds’ chorus brings a smile to David Sibley’s face.

[BIRD CALLS]

CURWOOD: So, who are we listening to here?

SIBLEY: Ahhh, we're hearing Northern Cardinal, Blue-grey Gnatcatcher, Warbling Vireo, Red-winged Blackbird, Swamp Sparrow, Yellow Warbler, Common Grackle, Catbird, Common Yellowthroat, Canada Goose.

CURWOOD: Gee, I think that you probably just doubled my life list for around here.

[LAUGHS]

SIBLEY: I’m hearing a Northern Waterthrush singing in the bushes right there. That chirping sound descending in pitch.

[CALLS OF NORTHERN WATERTHRUSH]

CURWOOD: A Northern Waterthrush. Let’s look in your book. Where are we to find a Northern Waterthrush?

SIBLEY: It’s one of the warblers. So it’ll be...

CURWOOD:...in the warbler section back here.

[FLIPS THE PAGE]

SIBLEY: Right here.

CURWOOD: You’ve added something I didn’t see before in your other works which is a description of what the bird sounds like. Can you read that?

SIBLEY: A song of loud of emphatic clear chirping notes generally falling in pitch and accelerating loosely paired or tripled with little variation; called a loud hard sprik rising with strong K sound; flight call a buzzy high slightly rising zip.

An early morning in the Great Meadows National Refuge, located in Concord, Massachusetts. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Your descriptions are almost the way people describe wine, with a little bit of this flavor and a hint of that and all that.

SIBLEY: Yes, we do. It’s so difficult to describe in words what a bird sounds like. You end up using words like mellow and rich and liquid and sharp and it does just sound like the descriptions of taste. [LAUGHS] If the words are used consistently and used repeatedly you kind of get a sense of what each one means and you’ll learn that yes, that thrushes tend to have a liquid sound, and orioles and robins, their voices have a rich sound. It’s fun to try to come up with words to describe all these sounds.

CURWOOD: So your first book, really, so many folks see that as a gold standard for a birding guide. So why do another?

SIBLEY: As soon as the first book went to the printer back in 2000, I started taking notes and gathering information about things I wanted to change, or new things I had learned. I look at those paintings and think I could do this or that a little bit better, or add details, or add new illustrations to show different things.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s take a step out into the meadow.

SIBLEY: Alright. Let’s head down this path through the marsh here.

[FOOTSTEPS ON DIRT PATH, BIRD SONG]

SIBLEY: So I’m hearing a Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, Grey Catbird, Red-winged Blackbird singing.

[SONG OF INDIGO BUNTING]

Up above us there’s an Indigo Bunting singing up in the Maple right there, that high pitched sound, and every note is repeated, every phrase is repeated. The Indigo Bunting is a migrant. They don’t normally nest right here. So we can be confident that that bird probably just arrived last night. It probably flew up from the south last night, dropped in here sometime early this morning, and now it’s checking things out, gets up to the top of the tree and sings a little bit to see if anyone answers, and it’s kind of assessing the area to figure out if this is a good place to stay for the summer, and I think the answer’s going to be no. It’s too wet for Indigo Buntings. They don’t nest here, so it’ll move on. Maybe it’s already moved on. I don’t hear it anymore.

Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb and Steve Curwood go birding with guide David Sibley. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

This time of year, all the birds are singing, and it’s so much easier to walk through an area listening and hear what’s around, and it’s possible to identify every species, essentially every sound can be identified.

[GEESE HONKING]

SIBLEY: One of the things about birdsongs is their ears work a lot faster than ours. Their ears and their brain processing of sounds works a lot faster than we do, so they’re hearing an incredible amount of information more than we do. If you take a bird sound and slow it down to about a quarter speed, then you start to hear the kind of detail they’re hearing.

CURWOOD: So why is it that birds are, well, singing the loudest in the morning?

SIBLEY: I think the song in the morning is mostly kind of a checking in with the neighbors. Male birds sing to kind of defend their territory, to mark the edges of their territory. So they’ll circle around to perches at the edge of their territory and sing from those spots and their neighbors, they’ll recognize the sounds of their neighbors. They recognize each other. So the morning song is kind of just an announcement that, “I’m still here. Are you still here? Yes. OK. Territorial boundaries still enforced? Yes. OK.”

CURWOOD: And what about the migrants?

SIBLEY: Migrants, they might be singing to sort of test the area, to see if they get a response, to see if there’s a female nearby that might respond to the song. But mostly, it’s probably just hormones. It kind of goes back to the old poetic thing about birdsong just being an outpouring of joy, the uncontrollable urge to sing with the dawn of the spring morn, and these migrants, they’re near their breeding grounds here, they’re heading north, they’re just about to enter this phase of life where they’ll find a mate, they’ll set up a territory, raise young, and they just can’t control themselves. They sing at dawn.

CURWOOD: One of the things that has certainly changed about birding is our awareness that the climate is shifting, and that means that birds are shifting. How do you account for that when you do a habitat range in your books?

SIBLEY: In the 40 plus years since I’ve been birding, starting in Connecticut in the 1970s and now in Massachusetts, I see really big changes in birds. Some species have increased tremendously like Canada goose, Wild turkey, Red-bellied Woodpecker. Some of those species are southern birds that are moving north, and some of that’s probably due to climate change, but there are all kinds of other things going on in bird populations, and a lot of species have declined. But it’s about equal numbers of sort of winners and losers in the last 40 years, so over that span of time, 40 years, the maps and the bird guide would have changed a lot for probably 10 percent of the species.

CURWOOD: 10 percent of the species in different places 40 years ago. What accounts for that, do you think?

SIBLEY: Mostly it’s changes in habitat. The big change here in the northeast is that, well, 100 years ago it was almost all farmland, there was very little forest. And 40 years ago, we were just coming out of that, and now, a lot of farms have been left to grow up to forest and all the suburbs that were built in the ‘50s and ‘60s with trees planted then, the trees are now 60 years old and big enough to support a lot of forest birds, the ones that can coexist with people like robins and bluejays and grackles and Wild turkey and even birds like Pileated woodpecker. It was incredibly rare in Connecticut when I was a kid in the ’70s, and now they’re pretty widespread and found in the suburbs.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and hungry in the suburbs too.

SIBLEY: Yes, sometimes unpopular when they look for food in the siding your house, but they can do a lot of damage. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So you’re an ornithologist, you’re a writer and an artist. And you hand-paint every one of these bird pictures in your guide yourself. Tell me about the process and why you do it.

SIBLEY: When I’m in the field, I’m watching birds, I’m studying shape and posture and doing pencil sketches and then, so I have years and years, thousands and thousands of pencil sketches from the field. When I’m back in the studio I get all of my pencil sketches and I use photographs as reference to get all the details right, and I work on paintings in the studio. For me, and we’re really lucky in this time now, and it’s really in the last 15 years that photographs have become so numerous, to have so many photographers doing such good work and everything’s available on the internet that for the work that I do, I can find hundreds of photographs of every species. Illustrators like Peterson had to use specimens for their reference material.

CURWOOD: Yes, I guess Audubon famously shot everything he drew.

SIBLEY: Yes, he did, and he was traveling through the woods with nothing but a shotgun and his painting supplies. He didn’t have binoculars, he didn’t have cameras, nobody had a camera. There weren’t even books he could carry with him to help identify the birds. It was just him and his paintings.

Sibley points out a songbird. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUNDS OF SWANS FLYING]

SIBLEY: A pair of mute swans flying by.

CURWOOD: Not so mute.

SIBLEY:[LAUGHS] Yeah, that sound is their wings. They do make vocal sounds also. They’re not entirely mute, but that sound is produced by their wing feathers. Just sort of humming through the air with each wing stroke.

CURWOOD: So, I have to ask you, what got you hooked on birding?

SIBLEY: I have always been interested in birding. My father’s an ornithologist so I’m sure that had something to do with it.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess so.

SIBLEY: But, yeah, birding was a part of what our family did, I just really enjoyed it, the birding and I was always drawing birds also.

CURWOOD: So when did you realize that, well, this would be the work part of your life?

SIBLEY: As a young teenager in Connecticut, I was going out on the weekends with people from the New Haven bird club and watching birds, identifying birds, learning about them. People were supportive of my interest in birds and my drawing, very encouraging. And Roger Tory Peterson who had illustrated the most popular field guide at the time lived about 20 miles away. I met him a few times when I was a kid, and to have him flip through a few pages of my sketchbook and look at it and say, “Oh, these are very nice. Keep it up.” And I think I grew up with the idea that writing a field guide was a perfectly viable career choice. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in birds.

CURWOOD: Well, that’s a better way to grow up birding than being dragged out at five in the morning to stand in the cold.

SIBLEY: [LAUGHS] We did plenty of that too.

CURWOOD: There’s something about birding, which even if you don’t want to, it kind of grabs you.

SIBLEY: Yes, and the popularity of birding has increased so much in the last 40 years. When I started out in the ’70s, it was rare to see another birdwatcher, and now, you go to a place like Great Meadows here, the parking lot at times will be filled with cars of birdwatchers. I think it’s just a desire to connect with nature, and birdwatching is just a way, it’s an excuse to set the alarm for 4:30 in the morning and go out even if it’s raining or windy, and get outdoors and just experience that. And it’s not so much about the birds, the birds are kind of the hook, the pull that gets us out there, but to a birdwatcher, it’s as much just the experience of being outdoors and feeling the change in weather and seeing the seasons change and being aware of those patterns. I think that's the real draw.

CURWOOD: David Sibley, thank you so much.

SIBLEY: Thanks, it's been a pleasure. What a great morning.

CURWOOD: David Sibley’s new book is called The Sibley Guide to Birds, Second Edition.

Related links:

- Sibley Guide Books

- Info about the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

[MUSIC: Gary Burton/Chick Corea “What Game Shall We Play Today” from Crystal Silence (ECM Records 1973)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth