July 15, 2016

Air Date: July 15, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Congress Approves GMO Labels

View the page for this story

Congress just passed legislation to create a national GMO labeling standard. If signed into law, it would override more stringent measures that went into effect in Vermont on July 1st. Host Steve Curwood called upon Patty Lovera, the Assistant Director of the advocacy group Food And Water Watch, to explain the dangerous loopholes she sees in the bill. (06:30)

Stopping the Public Coal Swindle

View the page for this story

Critics have long argued that royalties paid for coal mined on public lands are way under fair values. Now the Obama Administration is reassessing coal leases and royalties. University of Chicago economist Michael Greenstone tells host Steve Curwood the fees companies pay should reflect market prices also include the lifetime cost of the climate damage this carbon-rich fuel causes. (07:25)

Nesting Turtles at Home in Suburbia

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Habitat loss, the dangers of roadways, and other hazards have reduced the population of the locally threatened Blanding’s turtle in the Northeast. The nonprofit Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has teamed up with local residents to safeguard the nests that mother Blanding’s turtles make in their neighborhoods, often in the landscaping of homeowners. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering tagged along with GWC Executive Director Bryan Windmiller and his team in Concord, Massachusetts to tell the story. (19:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In their weekly round-up, Living On Earth Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra talk about a congressman who’s trying to restrict government-funded airline flights for EPA employees, yet another assassination of an environmental activists in Honduras, and a history of air conditioning in America. (05:10)

The Whistling Caribbean

View the page for this story

Some ocean waves are for riding, and some “whistle.” A current in Caribbean Sea reverberates like it’s in a 120-mile long flute, according to satellite data. Joanne Williams of the UK’s National Oceanographic Centre tells host Steve Curwood that if it’s sped up and sonified, the note of this super-long wave resonates with A Flat. (05:30)

When Mother is a Hungry Bear

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

A skinny polar bear walks slowly along the shore of Akpatok Island in Hudson Strait. Her cubs are nowhere to be seen, and her body bears signs of a fight. Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender watches her painful progress and wonders what she’s feeling. (03:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

160715 Final Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Patty Lovera, Michael Greenstone, Joanne Williams,

REPORTER: Jenni Doering, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The Obama administration is rethinking the royalty system for coal mined on public land to take account of the true costs.

GREENSTONE: So there’s a few things that smell a little fishy about the current system. The climate damages are about six times the market value of the coal. I don’t think one has to be a raving environmentalist to think, "Hey, maybe that’s not such a good deal."

CURWOOD: Recalibrating the price of coal. Also, oceanographers discover a new wave phenomenon. You could call it “the Caribbean whistle.”

WILLIAMS: So, in a whistle that you blow down as an instrument, you’ve got a current of air going through the whistle and it resonates at the frequency that fits nicely in that size of instrument, and that’s the sort of thing that we’ve got going on in the Caribbean.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Congress Approves GMO Labels

The safety of bioengineered food remains a point of contention among scientists. (Photo: Don Graham, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Congress has passed a bill that would require processors to tell consumers which foods contain genetically modified ingredients, although there are important exceptions. This would pre-empt state measures, including a stronger labeling law in Vermont that went into effect at the beginning of July. The food industry is generally urging President Obama to sign it into law, but critics including Patty Lovera of Food and Water Watch say the legislation sells the public short and should be vetoed. Patty Lovera joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Patty.

LOVERA: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So what does this GMO bill at the federal level mean for consumers, should President Obama sign it?

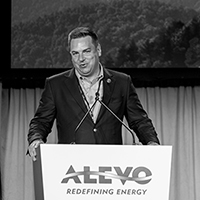

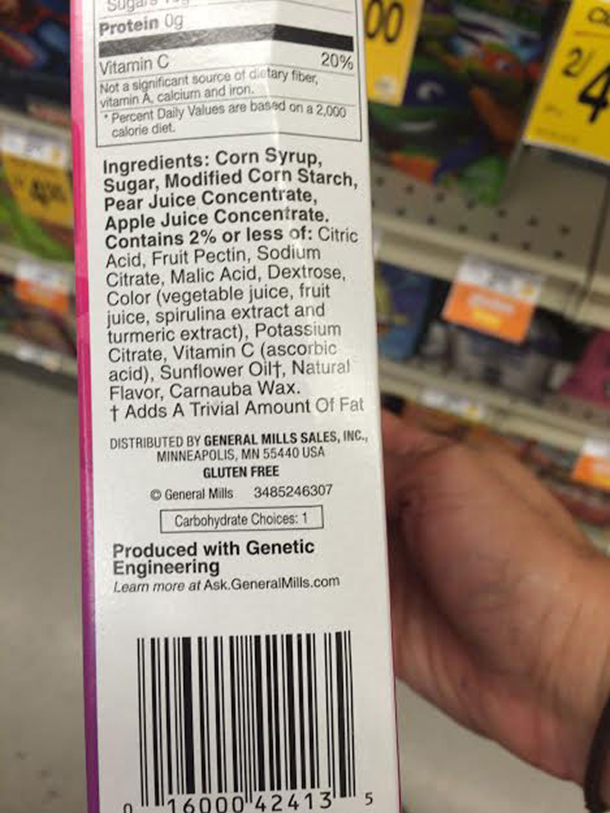

LOVERA: So the bill is Congress saying that states cannot pass mandatory labeling laws and it replaces, you know, a good state law for somebody that went first and figured it out. It replaces that state law with supposedly a new national labeling system. But it's really filled with loopholes that aren't going to give people labeling. It has a terrible definition of what a GMO is, so it would leave a lot of things uncovered. The requirement itself of how you disclose gives companies an option of putting the words on the package, which you know that they don't want to do, or using things like a QR code which we think is not acceptable because lots of folks can't access that technology. It has no enforcement provisions. There's some concerns in there about how this definition, that poor definition, would be used in other parts of our food policy like the organic standards. The list just goes on and on and on, and we think the net effect is you're taking away state law that's providing labeling, and you're creating a system that’s really not going to result in meaningful labeling for consumers.

A GMO label on a product sold in Vermont, in accordance with their new GMO legislation. (Photo: Courtesy of Patty Lovera)

CURWOOD: What are your thoughts on another point of contention, namely that many ingredients derived from genetically modified crops wouldn't require a label?

LOVERA: Yes, there's a long list of problems...That's on it too. So they put a definition in the bill that there's a lot of dispute about. So the Food and Drug Administration wrote a memo that said, yeah, we read this definition as saying a lot of the current genetically engineered ingredients on the market, things coming from sugar beets, cooking oil from soybeans, things like that could be processed to the point they don't contain genetic material anymore and under this definition they may not be considered a bioengineered ingredient that would trigger labeling and then there's yet another piece of that definition that is causing a lot of confusion about the trait. You know, the reason the crop has been engineered as for some specific trait, and there's some very strange language in this definition. It has to be a bioengineered ingredient has a trait that can't be found in nature. Lots of traits can be found in nature. They just can't necessarily be found in these crops, so this definition is incredibly, incredibly worrisome and is one of those loopholes I'm talking about that may leave a lot of foods unlabeled in any useful way.

CURWOOD: You say this legislation will create a law that has no enforcement provision. How is it a law then?

LOVERA: [LAUGHS] It says explicitly that USDA could not order a recall for being mislabeled, and there's really no other provision. Most usually when you write a law, you say, “This is what the penalties are.” There's no penalty discussion in here, and when asked the supporters of the bill have said things like, “Well, if you're not being accurate, somebody could use state laws on fraud to go after you,” but that was a choice, and they chose not to put teeth in it.

Senators Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), left, and Pat Roberts (R-KS), right, teamed up for the bipartisan GMO labeling effort. Senator Roberts’ voluntary labeling scheme was shot down earlier this year. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, recently the National Academies of Science have found that GMOs are both safe and "no different from other foods". Given the official approval, why do you think it's important to label them?

LOVERA: So, we think that the debate on safety is not over yet. We actually had a number of critiques of the national academies paper and critiqued some of the folks who have to write it, many of whom had financial ties to the biotechnology industry. So, we think the science conversation is not over about safety, but when you don't tell people where they are, you're not going to be able to track if there's a problem. We're not telling people they are eating this to see if we can then later determined there's a negative effect. And then there are other reasons besides health. You might think about this technology. There's a tremendous, corporate kind of control facet to this issue in terms of patenting seeds, very expensive intellectual property agreements. There's lots of farmers who are concerned about GMOs. There's a chemical use, public health, worker health and environmental impact of the chemical use facet to this. This is a different way of producing food, and there's lots of reasons people might want to know about it and they might like it and want to seek it out and they need to know where it is. This is a really big fight over a very basic concept of just saying, “We used it or we didn't,” and then letting people decide for themselves.

CURWOOD: To what extent was this legislation written by industry in your view?

LOVERA: That is a great question that we don't get to know. So there's a tremendous...This legislation came out of the Senate. They tried to pass a different version in March, and the bill failed, and so after the failure in March the two leaders of the Senate agriculture committee, the Democrat and the Republican - Debbie Stabenow from Michigan is the Democrat, Pat Roberts from Kansas is the Republican - They went into these negotiations, and they wrote this new version of the bill. It never went through committee again. It never had a hearing. There were very few, I mean, essentially no opportunities for meaningful amendments, so that leaves us to wonder, “Who was in that room?” We weren't. Lots of other senators' offices were not. So, this to us has industry's fingerprints all over it, but we didn't see the process because process was very secret.

CURWOOD: What reading do you get from the White House? What will they be doing with this?

Patty Lovera heads up the food team at the non-profit Food And Water Watch. (Photo: courtesy of Patty Lovera)

LOVERA: Yeah, it's a good question what the White House is going to do. We have the secretary of agriculture who is a big fan of these QR codes. We've heard him talking about, "We need to solve this problem we have with this dispute about labeling." He's been saying that for over a year so that's worrisome for us. We had candidate Obama in 2007 talking about people who should know what's in their food. We should label GMOs, so we think we have work to do, and lots and lots and lots of folks are contacting the White House, and then you need to veto this bill and live up to the campaign promise. So it's not clear.

CURWOOD: So what's your ideal vision for a GMO labeling standard here in the United States?

LOVERA: Well, ideally we would have a national standard that gave people on a package, words on a package, mandatory labeling with a good definition. We don't have a Congress that's going do that. That's pretty clear. So in the interim if states were making progress on this, we think that's a good step, and this is how we change lots of laws. The states go first on lots of issues, and eventually we build to an acceptable national standard. This is the industry coming to Washington throwing their weight around and trying to stop the momentum that people have achieved at the state level.

CURWOOD: Patty Lovera is assistant director of Food and Water Watch in Washington. Patty, thanks so much for taking the time.

LOVERA: All right, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Bioengineered Food Bill Text

- Vermont GMO labeling law text

- About Patty Lovera

Stopping the Public Coal Swindle

41% of US coal production comes from publicly owned lands, most of it in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana. When companies pay less to lease this land and game the royalty system, it’s taxpayers who get shortchanged. (Photo: WildEarth Guardians, Flickr CC BY-ND-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s been six months since the Obama administration put a moratorium on new coal leases on public lands. During the planned, three-year pause the Department of the Interior is reviewing its management of taxpayer-owned coal, including its impact on global warming. And earlier this month, Interior moved to close a major loophole that has left royalties paid to the government artificially low for decades. We called up Michael Greenstone, a former chief economist for the Obama White House to explain. Professor Greenstone now teaches at the University of Chicago. Welcome to Living on Earth.

GREENSTONE: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, let's go with the basics at first. How does public land get leased for coal extraction? What's the process?

GREENSTONE: So there's a three part process. The first is that the federal government puts up tracts of land that are eligible to be released, and then companies can bid an amount to have access to that land. That's called the bonus bid, and then after that they pay a rental fee of $3 per year per acre, and then finally they pay a production royalty fee, which is supposed to be 12.5 percent of the value, whatever comes out of the land.

CURWOOD: What's wrong with the present system in your view?

The coal mined on government land in Wyoming and Montana is about 70% cheaper, per unit of energy it contains, than its Appalachian counterpart from private mines. The publicly mined coal price is kept low largely by the government’s outdated leasing system. (Photo: Greg Goebel, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GREENSTONE: Yes, so there's a few things that smell a little fishy about the current system. First is that in the bonus bid phase, where different companies are in principle bidding and the taxpayer is being protected by them competing against each other, you actually have, according to a GAO report, that 90 percent of the leases since 1991 have had only one bidder. I'm not an expert at bidding on coal land, but if I didn't have to compete against anyone, I'm pretty sure I could get a good price.

CURWOOD: OK. So the bidding system is suspect. What about the next phase?

GREENSTONE: So the rental fee, that seems straight forward. Companies pay $3 per year per acre. But the third phase, the production royalties phase, also has a feel that something might not be quite right. There, the way it's supposed to work is that the federal government should collect 12.5 percent of whatever the value of the product is, in this case of coal. But recent investigations suggest that actually what is happening is that the bidder is selling the coal to a company that it has partial ownership in at a very low price, and then the 12.5 percent is collected on that low price, and then that company that is partially owned or wholly owned by the original leaser then sells it at the global price for coal. And in that sense, the 12.5 percent is being collected on a much smaller number than is fair.

CURWOOD: So talk us through the new Department of Interior regulations. How are they going to change that system?

Though many government regulations account for the social cost of carbon – an economic metric set at $40 per ton – environmental damage is not a factor in our current coal leasing system. That helps explain why the environmental cost of coal is a whopping six times than its market value. (Photo: Stannate, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GREENSTONE: The idea is a requirement that the 12.5 percent be collected on an arm's length transaction. So that is effectively on the final price and not on what I sell it to my brother or what I sell it to my cousin for. So, yeah, I think when one examines a coal leasing program, a different area that is probably not working as well as it should is that the environmental impacts of the leasing coal are not taken into account in the leasing program at all. The US government has something called the social cost of carbon, and that's a monetary value of the damages associated with the release of an extra ton of CO2 into the atmosphere. The number that they use - and full disclosure, I was working in the Obama administration and helped develop that number - but the number they use is $40 a ton. So that is an extra ton of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere is expected to cause $40 worth of climate damages.

CURWOOD: And how much does coal cost in the marketplace?

GREENSTONE: So, what's fascinating is the spot price, or the value of a MMBTU of coal is about 66 cents. The climate damages associated with that same MMBTU are about $3.89. So just to put that in very plain English, the climate damages are about six times the market value of the coal. I don't think that one has to be a raving environmentalist to think, “Hey, maybe that's not a good deal.”

CURWOOD: So, how often does the government take into account the social cost of carbon when setting regulations?

GREENSTONE: Yeah, so the U.S. government first set a social cost of carbon in 2009, and then there was very small revisions of it in 2010 and I think again in 2013, and it has at this point been used in scores of regulations. And so basically any regulation that has carbon reduction, be it café standards or energy efficiency standards, all have the benefit of those regulations, reductions in CO2. And what the social cost of carbon does is it allows one to convert those tons of CO2 into dollars, and that way one can compare the benefits of regulations that have CO2 as a benefit to the costs which are measured in dollars. The way that this could be incorporated into the leasing of access to fossil fuels on federal lands, be it coal, natural gas, or petroleum, would be if we return to the bonus bid phase of the auction, and in that phase one could just set a reserve price, and that reserve price would be equal to the climate damages, and so if no one was willing to pay more than that reserve price, that is the environmental damages, then the resource wouldn't be used, but if its use in the marketplace was more valuable than that environmentally determined reserve price, then the resource would be used and provided all the benefits that energy helps to provide.

Michael Greenstone is the Milton Friedman Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago, where he directs the Energy Policy Institute. (Photo: Matt Marton)

CURWOOD: So, that would be a piece of change. Not only would you be paying a one-time leasing fee but you'd essentially be paying the surcharge on a lifetime of extracting. But this would effectively mean, leave it in the ground.

GREENSTONE: Well, that depends on the resource. In the case of Powder River Basin coal, on average, the kind of damages are much larger than the market value and I think many tracts would then become non-economical to utilize. But in the case of natural gas and the case of petroleum, the benefits measured by the spot price that those resources go for, exceed the climate damages and I think we would continue to use them, although there would be a greater collection of revenue for the federal government that could be used for a variety of things.

CURWOOD: So how would this affect export coal?

GREENSTONE: This would probably reduce exporting of coal, and I think what is at the heart of that question is that emissions have the same effect wherever they occur, and this would mean that we were not just simply transferring emissions from the United States to another country.

CURWOOD: Is that what we're doing now?

GREENSTONE: There's a risk that when we have things like the Clean Power plan that it becomes expensive to burn coal in the US power system and that the coal gets exported elsewhere and used elsewhere. By embedding the social cost of carbon, or the monetized value of climate damages in the initial leasing price, that is a hedge or a safeguard against them.

CURWOOD: So, what do you say to people whose say, you know, we just can't trust the markets to get us off dirty fuels.

GREENSTONE: Well, they are right about that in the following sense. We have not set up markets by and large where the prices of energy reflect the damages of different fuels, and we're just beginning to alter markets. But markets in the end of the day give us what we asked them to give us, and so, as long as prices don't reflect climate damages, we will make choices that don't take account of that.

CURWOOD: Michael Greenstone is at the University of Chicago where he directs the Energy Policy Institute. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

GREENSTONE: Thank you for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- The Department of the Interior’s press release

- The Washington Post: “Obama Admin Changing Coal Royalty Program to Boost Revenue”

- Inside Climate News: “White House: Raising Coal Royalties a Boon for Taxpayers, and for the Climate”

- The White House Council of Economic Advisors’ report: “The Economics of Coal Leasing on Federal Lands: Ensuring a Fair Return to Taxpayers”

- Michael Greenstone for The New York Times: “There’s a Formula for Deciding When to Extract Fossil Fuels”

[MUSIC: Flynn Cohen, “Navajo Boy,” Mellow Yell, traditional American, Deadstring Music]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...helping turtles make it to teenage and beyond, but they’re not called Leonardo, or Michelangelo. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Flynn Cohen, “Navajo Boy,” Mellow Yell, traditional American, Deadstring Music]

Nesting Turtles at Home in Suburbia

The bright yellow throat of the Blanding’s turtle can help biologists recognize one from a distance (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Head Start is a US government program designed to give children from vulnerable, low-income families a better shot at doing well in school as well as later in life. Today, we have a story of another intervention program, based in the wetlands of Concord, Massachusetts. But this one is for turtles, and Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering went to check it out.

[SOUNDS OF A SUMMER EVENING]

DOERING: On a summer evening at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, you’re surrounded by tall reeds, lily pads on shallow ponds, and turtles. And if you’re really lucky, you’ll spot the dark, high-domed shell and bright yellow throat of a Blanding’s turtle basking on a log. The turtles are right at home here, but Massachusetts lists them as a threatened species. That’s partly because young Blanding’s turtles face many dangers.

WINDMILLER: They have maybe a 1 in 80, 1 in 100 chance of living to be adults.

Chris Hickling holds up a radiotracking antenna at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

DOERING: That’s Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation. The nonprofit is working to shift those odds and give baby Blanding’s turtles a better start in life – appropriately -- by sending these youngsters to school so young humans can care for them and raise them for a year.

WINDMILLER: And we call that “head starting,” you know, from like from the human Head Start program. We give the little turtles a head start in life. We give them at least a forty-fold increase in their chances of surviving to adulthood.

DOERING: The head start cycle begins each summer during turtle nesting season, when Bryan and his team search for the mother Blanding’s nests to protect them. I tag along, and we start by getting our feet wet.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

When he checks the first hoop trap, Chris finds a Blanding’s turtle inside (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: One of the interns working at Grassroots this summer wades into the thigh-deep water at Great Meadows.

HICKLING: I’m Chris Hickling, I’m going to be a rising senior at the University of Richmond.

[MORE SPLASHING SOUNDS]

DOERING: Wearing rubber chest waders like Chris, I follow him into the pond and we head for a large mesh trap set up a few yards from the muddy bank.

WINDMILLER: So that we can determine how many there are, how many boys, how many girls, how many young ones, how many old ones, and so that we can get hold of some of the ladies and we can radio track them to where they nest, we start out by trapping them.

Chris tells Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering about a Blanding’s turtle uncovered from the trap. (Photo: Don Lyman)

[MORE WATER SOUNDS]

DOERING: Chris opens the trap.

DOERING: All right, what have we got?

HICKLING: We have two painted turtles, and one Blanding’s turtle; and this Blanding’s turtle does not appear to be fully grown – the shell’s pretty worn for a young turtle.

DOERING The team uses a marking system that gives each turtle a number so they can record it in a database. This turtle’s shell is about six inches long, and Chris points to marks notched around the edge.

HICKLING: So how we mark them is -- so these are the ones, the tens, the hundreds, and the thousands. And each of them has a notch number. So this’d be one, two, three, you see he’s notched here.

DOERING: So it’s like going around the face of a clock?

Bryan Windmiller with a larger Blanding’s turtle caught in the trap (Photo: Don Lyman)

HICKLING: Exactly.

DOERING: Counting around clockwise.

HICKLING: Clockwise, exactly. So this one was raised in one of the classrooms around here, at some point.

DOERING: Bryan takes a look at the shell markings and identifies this turtle as number 401.

WINDMILLER: That’s really, really cool. So that turtle hatched in 2008, released in 2009, and that’s actually the first year that we head started turtles, and this would have been the first in that group.

DOERING: The head start program is crucial because Blanding’s turtle hatchlings are an easy snack for predators. Their tiny, half-dollar-sized shells are actually folded inside the egg, and Bryan Windmiller says they’re still soft for months after they hatch.

WINDMILLER: So we take them when they’re at that real vulnerable stage and we give them to schools, and they raise the turtles for nine months, take care of them all winter, keep them warm, feed the turtles as much as they want. And in that environment, they grow super quick, so when we let them go, they’re on average about 12 times, sometimes 15 or 20 times, heavier. They’ve got a much bigger shell, really strong shell. They don’t have to worry about chipmunks, they don’t have to worry about bullfrogs, they don’t have to worry about blue jays, and garter snakes.

Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge covers more than 3,800 acres (Photo: Stephanie Liszewski / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

DOERING: But natural predators aren’t the only hazards that threaten the turtle hatchlings.

WINDMILLER: Sometimes they’d be destroyed completely unintentionally by people, because sometimes they nest in farm fields that would get plowed, or they nest in people’s perennial beds that might get turned over and stuff like that.

DOERING: Bryan says that because of these threats -- from both natural predators and human development -- the Blanding’s turtle population here has been declining for decades.

WINDMILLER: There are only about 50 adult Blanding’s turtles here at Great Meadows, spread among a bunch of wetlands. And that’s down from probably 150 in the early 1970s, so our overall goal here is to help restore this population.

DOERING: And despite having just a few dozen adult Blanding’s turtles, the population at Great Meadows is actually the third largest in Massachusetts and the fifth largest in the Northeast. So boosting numbers here could give the species a significant leg up locally.

Sam Linde, another Grassroots Wildlife Conservation intern, holds one of the Blanding’s turtles caught in the trap (Photo: Don Lyman)

[WATER SOUNDS]

DOERING: In the pond at Great Meadows, Chris and I wade through the cool water to check another trap.

HICKLING: Whoa! Another Blanding’s. A big one.

DOERING: That’s really big. The shell is about nine inches long and dome-shaped.

HICKLING: Yeah. So that’s a male, because it doesn’t have a radio tracker. So that’s the easiest way to tell, because we don’t, you know…We’re concerned with finding the nests and the females, and the males have nothing to do with it at that point. This is one of the bigger ones I’ve seen. His shell’s very worn, and you can see the algae all on the shell here.

DOERING: Bryan takes a look at the turtle and recognizes it as one he’s caught before.

WINDMILLER: By looking at this guy, even though we first caught him about five years ago, this turtle is at least sixty.

Chris and Sam measure a larger Blanding’s turtle (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: Blanding’s turtles have a similar lifespan to humans. Scientists guess that they can live up to ninety years, but no one is sure because there’s not enough data about the species yet. Bryan explains that these turtles we’ve just caught will contribute a couple more data points to what’s known about them.

WINDMILLER: So we’ll get these guys measured and weighed. Then they’ll be released here, but we’re gonna start on our main business for the evening, which is looking for the moms. So we’ll start by going up in the tower, and we’re gonna check with a radio tracking receiver. We’re gonna check on the signals of the moms that haven’t nested yet around here. And we’ll get a sense of where they are, and then we’re gonna go look for some of them.

[STEPS ON TOWER SOUNDS]

DOERING: The metal, twenty-foot-high tower overlooks most of Great Meadows and is a good high point for radio tracking. We meet up with Lea Kablik, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who helps with the tracking. Lea turns on the receiver and holds the antenna over her head, pointing it in different directions.

Bryan Windmiller examines turtle number 401, one of the very first turtles in Grassroots Wildlife Conservation’s head-start program. (Photo: Don Lyman)

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

DOERING: The beeping sound clues Lea in to where the turtle could be. It’s faint right now because this turtle’s not close.

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

DOERING: Do they all sound the same?

KABLIK: Yeah, each beep sounds the same as all the others. It’s just knowing what frequency that you have programmed into the receiver.

WINDMILLER: The turtle has a radio station. And it’s just like all the turtle radio stations. The different radio turtle stations are playing exactly the same tune, but you can listen to all the different ones that sound exactly the same just by dialing in your particular channel. So this year, altogether we’re tracking eleven females here at Great Meadows, one of whom we’re just not picking up a signal from. Two have nested, and so, with the one that’s not working, that leaves us eight to run after right now. We should go start off looking for 2028.

Bryan explains the predators that like to eat turtle eggs. A skunk dug up and ate most of the eggs in this snapping turtle nest, but the Grassroots Wildlife Conservation team was able to protect the remaining eggs with a mesh screen. (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: We drive to a quiet neighborhood just a short distance away. The lawns are well-kept, the backyards have big shade trees, and we see several residents hanging out on their porches on this fine June evening.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, well, we’re over at the side of this house, and this is where Chris and Stephanie and Lea last night tracked turtle number 2028, and they put a little thread bobbin on her just as a visual way of tracking her in case she decided to nest late at night. Blanding’s turtles almost always nest as it’s getting dark, and usually they’re done by 11:00 or so, but some of them like to stay really late, and we don’t, so if people need to leave, then sometimes we put these thread bobbins. So as the turtle walks, the thread just spools out until it runs out, and the turtle just walks away. They don’t detain the turtle, but unfortunately in this case the thread broke, so now we’ll go find the turtle with her radio.

DOERING: Actually, it turns out a well-meaning neighbor thought the turtle was trapped, and the good Samaritan cut the thread. But on the whole, Bryan says, having the neighborhood involved is a great boon for turtle conservation.

Blanding’s turtles will sometimes make their nest next to concrete curbs (Photo: Stephanie Liszewski / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

WINDMILLER: If you do it right, if you involve the people to the extent that you can. The local human population can be an asset for conservation, instead of a problem. Because that’s the tendency. Biologists assume that people are always the problem. And yet, here, the turtles are nesting in people’s front yards. People are on – They tell us, they call us when they see turtles, they’re looking out for the turtles, they’re looking out for the nests. We have several thousand schoolkids in Massachusetts who raise young turtles for us as part of this conservation program, so people are in all kinds of ways directly helping out.

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

DOERING: Lea starts moving around with the radio tracking equipment. Getting an accurate signal is proving difficult because the radio waves bounce off of the flat sides of the houses. I ask Bryan where the turtle we’re looking for, number 2028, would most likely be nesting.

WINDMILLER: Well, if she’s going to be nesting, she’s going to be nesting in an open, relatively sunny place. There’s a good chance the turtle right now is just continuing to kind of hide in some of the shrubs and plantings near the house. Blanding’s turtles take a long time. The moms are really meticulous about finding a good spot to nest, and they almost never nest the first night they come out of the water. They’ll often spend a few days, a week, sometimes, on land. Sometimes they’ll walk around…We’re just like chasing them around these neighborhoods, and they dig a few holes there, don’t like it, dig a few holes there, and check out an area, and sometimes they’ll go all the way back to the wetlands of Great Meadows, and they’ll hang out in the water and come back a few days later and finally nest.

Lea Kablik, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist, uses radio tracking equipment to try to find the nesting turtle (Photo: Don Lyman)

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

DOERING: We keep searching for 2028, but she’s proving elusive. A resident comes up to Lea to say she’d seen the turtle not long before.

NEIGHBOR: Okay, She was like right up on the pavement. And just wanted to let you know, that was the last time I saw her… maybe 45 minutes ago?

KABLIK: Oh, really! Okay.

NEIGHBOR: Yeah, yeah. So it wasn’t that long.

KABLIK: Okay, Thank you.

NEIGHBOR: And I’m not sure how fast they move!

KABLIK: Surprisingly fast.

‘Why did the turtle cross the road?’ Perhaps to make her nest in a Concord neighborhood. (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

NEIGHBOR: It had the antenna, and it had duct tape on it. She was basically where that watering can is.

WINDMILLER: By far the loudest spot is still in the ivy here.

[LOUDER RADIO TRACKING SOUNDS AND RUSTLING THROUGH IVY SOUNDS]

DOERING: Finally Bryan locates the turtle in the front yard of the house next door.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, she’s in the mulch.

HICKLING: Looks like she’s digging right now. You can see the pile of mulch just behind her that she’s kicked out of the way right there, on the edge.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, she’s definitely working. She’s certainly trying to do something over there.

DOERING: We need to be really quiet and keep our distance to make sure we don’t disturb her.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, I mean, you never know, the turtles are funny. Turtles who nest over here are obviously used to seeing people, and, I think, we caught this turtle – This is 2028 – I think we first caught this turtle ten years ago as a juvenile. It’s a pretty young mom. So she’s used to people. But just instinctively, Blanding’s turtles, all turtles are very wary when they’re first starting to commit to laying their eggs. Once they start laying their eggs, it’s like they go in a trance, and it doesn’t matter what’s going on around them. They’re going to try and finish. But before she actually starts laying her eggs and commits herself to her nesting spot, the best thing is to leave her be right now. She’s clearly, if she’s digging, she’s just started. So the best thing is for us to go concentrate on the other turtles, see where they are right now. And then we’ll come back and check on her later and see what she’s doing.

A Blanding’s turtle lays eggs in a nest at Borderland State Park in Massachusetts (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

DOERING: With Bryan and the rest of the team we walk over to the edge of Great Meadows, just down the street from the nesting turtle, to try to check on the other females. Chris explains how the tracking works each night.

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

HICKLING: The first thing we do is we usually check from the tower, to get kind of a signal of whether they’re in the lower or upper pool.

WINDMILLER: By this time of evening, if the turtle is in the swamp, she’s not gonna nest tonight. I mean, we’re like 99% sure. The turtles are individuals, you get some turtles that don’t read the books, want to do their own thing, and decide at 2:00 in the morning to come out and nest, and we’re just not gonna find that one. But the great majority of turtles, if they’re still in the water this time of evening, they’re not nesting tonight. So that’s really what we’re trying to do is sa”OK, is it in the water, that way, or are we missing it, and maybe it’s over here on land and we need to go find it.”

DOERING: The radio signals tell them that the other female turtles are all in the water, so we go back to the house where number 2028 is digging her nest in the mulch, to see if we can gauge her progress.

[CRICKETS, RUSTLING SOUNDS]

DOERING: It’s hard to tell, but Bryan has a guess.

[MORE CRICKETS, BIRDS]

Bryan gently digs in the mulch in front of a Concord home to uncover the first few eggs in turtle 2028’s nest. (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: She’s got a big hole. I think she’s just starting to cover up, because I couldn’t see the eggs in there, so I’m guessing that she’s already pushed some dirt over the top egg. Yeah, so at this point it’s nice because I’m in my neighborhood, and this is the point where I usually go over to my house, I sit down, watch a little bit of the Red Sox game if they’re still on, have a beer, come out in half an hour, check on her. She’ll probably spend, at this point, because she’s got still a lot of a hole to fill, she’ll probably spend another hour or so over here. They’re kind of very slow but steady.

DOERING: While we wait, Bryan explains that the ponds at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge aren’t actually natural. People created them as duck ponds for hunting, and many of the turtles still living at Great Meadows were here first.

WINDMILLER: They pre-date Great Meadows. Those ponds were created in the 1950s. So a lot of the older turtles at least were alive before those ponds were created. So they’re used to, or at least were born into, a radically different environment. Henry David Thoreau caught a Blanding’s turtle at Great Meadows in 1854. He killed it because a buddy of his, Louis Agassiz, had started the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard and really wanted a Blanding’s turtle for his collection, so Thoreau gave him a Blanding’s turtle and then wrote in his journal about how guilty he felt over killing the Balnding’s turtle, and you can still see the Blanding’s turtle on display at the MCZ at Harvard. And so the turtles were here, but the environment was totally different. I mean, you imagine it was called Great Meadows because a lot of it was the wetlands, were shallow, much more open, but not ponds.

The first few eggs in the nest dug by turtle 2028 (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: An hour or so later we return to the nest site…and turtle 2028 is gone. Bryan gently digs in the mulch to uncover her nest.

WINDMILLER: There we go.

DOERING: That’s pretty cool.

WINDMILLER: So we can just expose the top three eggs of her nest – actually you can see at least four. They’re about four inches deep. We’re very glad, she started about 7:30. It’s now about 11:30, looks like she pretty recently finished, so this is awesome. And this is really a typical kind of place for the Blanding’s turtles to nest here. She’s kind of near their stone paved walkway over to the front entrance of the house. And right in their mulch bed by their little perennial border about ten feet off the side of the house, a very nice spot for her nest. So now we’ll just cover it back up with dirt, like she did, like Mom did, and put a screen over it so raccoons and skunks can’t get it.

DOERING: Bryan goes to the car to get the protective metal screen and stakes.

[METAL CLINKING; CAR DOOR SLAMS]

WINDMILLER: So here in the suburbs it’s mostly skunks and raccoons. Foxes dig up turtle nests sometimes too. In this neighborhood in particular, there are a lot of skunks around here, and they’re very good at finding turtle eggs.

[METAL SOUNDS]

DOERING: Bryan thinks that nesting Blanding’s turtles may intentionally find refuge in housing developments.

Covering the nest with a mesh screen protects it from predators like skunks and raccoons (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: The great majority of them nest in places just like this, right by people’s houses. And at least I like to believe that the turtles have figured it out, that this is actually in many ways a better place for them to nest. First, they’re able to find these warmer little microhabitats, next to asphalt driveways, and little bits of landscape rock, and in mulched areas, where also the mulch will absorb some of the sun’s radiation. But in addition I think the turtles may have learned that when they nest in a place like this right up against somebody’s house, it’s really rare for raccoons and skunks to bother them.

[MORE METALLIC SOUNDS]

DOERING: He lays a square of chicken-wire mesh on the spot where the nest is buried and pushes metal stakes firmly into the mulch to hold it down.

[METAL SOUNDS]

DOERING: With the screen in place, turtle 2028’s nest is protected, and for tonight, the work of Bryan Windmiller, Chris Hickling, Lea Kablik, and Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is done.

WINDMILLER: And then we just wait, and we put the temperature loggers down by the eggs to monitor the nest temperature so we can try and guess whether they’re gonna be boys or girls. And just wait until late August or September, when the babies come out.

DOERING: And we plan to be back, too, to check on those babies when they hatch. For Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation’s Blanding’s Turtle Monitoring and Headstarting project

- 2014 report on GWC’s Blanding’s turtle project

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

- About Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

- Blanding’s turtle specimen caught by Henry David Thoreau for Louis Agassiz

- About Bryan Windmiller

- Watch a Blanding's turtle laying eggs

[MUSIC: Julie Scolnik/Franziska Huhn, “Piece en Forme de Habanera,” Bejeweled: Encore Gems For Flute and Harp, Maurice Ravel, Julie Scolnik & Franziska Huhn (publisher)]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org. Once again, comments at LOE.org. And visit our web page at LOE.org. That's LOE.org.

Coming up...the deep, deep bass voice of the singing sea is just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kotoja, “Vami Duwe (Let’s Dance),” One World, Danjuma Adamu, Putumayo]

Beyond the Headlines

Congressman Richard Hudson (R-NC) (Photo: Tom Raftery, Flickr CC BY-NC- SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Time to check in on stories beyond the headlines now. We’ll join Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org.

Hi there, Peter, kinda steamy down there in Conyers, Georgia, huh?

DYKSTRA: Well it’s 90 degrees or more for the umpteenth consecutive day here. We’ll talk a little bit later about the heat here, but, y’know, there have been a lot of intensive efforts to hamstring the US EPA from doing its job enforcing pollution laws and protecting the environment.

But here’s one that’s just a tiny bit over the top.

CURWOOD: Congress going over the top? Impossible!

DYKSTRA: An amendment on the bill to fund EPA, the Interior Department, the Forest Service and other agencies, Congressman Richard Hudson of North Carolina has attached the following amendment: “None of the funds made available by this Act may be used to pay the costs of any officer or employee of the Environmental Protection Agency for official travel by airplane.”

CURWOOD: So Representative Hudson wants to put the entire EPA in its own No-Fly-Zone.?

DYKSTRA: That’s right. In fairness to Mr. Hudson, nothing in the Amendment would prohibit EPA employees from paying for government travel out of their own pockets, nor is there a ban on traveling by Greyhound, covered wagon, stagecoach, or camel to monitor and inspect EPA’s over 1,300 Superfund sites and tens of thousands of permitted air and water dischargers, mine reclamation sites, pesticide application sites, hazardous materials production, and storage sites and more.

CURWOOD: Don’t forget Amtrak, if Congress doesn’t cut its budget any further. Do you get the impression that maybe the Congressman just doesn’t want EPA to be able to do its job?

DYKSTRA: It’s a little different than that, Steve. Congressman Hudson has previously introduced measures to prevent EPA from regulating backyard barbecues and NASCAR, and those are things that EPA apparently has no intention of doing.

CURWOOD: More fodder for a most interesting political year. What else did you bring us?

DYKSTRA: A little more of the same terrible news we’ve already heard enough of. Another environmental activist in Honduras was abducted and beaten to death last week. Lesbia Yaneth Urquia was a vocal opponent of hydro dam construction and mining on indigenous lands in the nation that had already been deemed the deadliest place on earth for environmentalists.

El Cajon Dam, Honduras (Photo: Dwwhyd, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: We reported on the murder of Berta Cáceres, the Honduran environmental leader and Goldman Prize winner, just a few months ago.

DYKSTRA: And since then, another Honduran activist, Nelson García, was also shot dead by Honduran security forces, and you reported on that, too. The watchdog group Global Witness says there have been over a hundred murders of activists in Honduras since the year 2010.

CURWOOD: The hate mail and harassment of activists and even some scientists gets pretty strong in this country, but a hundred murders in a relatively tiny nation like Honduras is another thing altogether. Give us something – and preferably not bad news - from the environmental history files for this week.

DYKSTRA: This month marks two anniversaries in the history of our trying to cool off. On July 14, 1847, a physician named John Gorrie was looking for a way to help his patients in Apalachicola, Florida, to stay cool while dealing with malaria and other tropical diseases. He designed a machine that cycles highly compressed air to produce ice. In Florida. In 1847!

CURWOOD: So every time we cool down with a summer beverage, we can thank Dr. John Gorrie?

DYKSTRA: Yes and no. Gorrie obtained a patent for his ice machine in 1851, but then his financial backer died, then Gorrie died four years later. He endured a lot of criticism from afar – the big northern newspapers scoffed at the idea that a crackpot claimed to have made ice in steamy Florida.

Other inventors came along using ammonia instead of compressed air, and ice-making came of age in the last half of the nineteenth century. It revolutionized the food industry and accelerated the race to conquer the Western US for cattle grazing and more, eventually enabled large-scale fisheries, filled billions of fast-food drink cups, and last month, allowed the National Hockey League to place a new team in Las Vegas. Hockey in Vegas, folks.

CURWOOD: Okay, so what’s your other cool invention?

DYKSTRA: On July 17, 1902, a good citizen of Pittsburgh named Willis Carrier laid out plans for what would become known as the world’s first air conditioning system. Today we would consider it to be more like the world’s first dehumidifier – he dried out the thick summer air, and later on, CARRIER and others combined his design with refrigeration machines to cool the air down.

Air conditioners on a high-rise apartment building (Photo: Arvind Grover, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And today folks consider air conditioning more of a necessity than a luxury – all with a huge carbon footprint.

DYKSTRA: Correct. In 1973, 52 percent of U.S. homes had AC; now, it’s over ninety percent.

I tried to look up the percentage of homes in Anchorage, Alaska that have AC, couldn’t find a hard number, but I found 24 Anchorage businesses listed as offering air conditioning repair.

CURWOOD: Wow. But at ninety percent, the US is nearly maxed out. What about the rest of the world?

DYKSTRA: You mean the world that’s getting wealthier and warmer at the same time? AC sales have doubled in China in the last five years, and one estimate says the city of Mumbai devotes 40 percent of its electric output just to power air conditioners.

The carbon footprint implications are enormous, but let’s look at what else AC has done.

There’s no count on the number of lives it may have saved during heat waves. Without it, there would be no huge metropolitan areas like Phoenix and Las Vegas, each with its own vanishing water supply, golf courses, and of course hockey franchises. Here in suburban Atlanta, on our umpteenth consecutive day of ninety degrees or more, I sit in comfort, occasionally gazing out the window to see my garden wilt. If the growth of clean energy and more efficient ways to stay cool can outpace the growth of AC, it can provide less costly comfort worldwide.

CURWOOD: Right. Otherwise, there’s the supreme irony that our ability to stay comfortable will just make things hotter.

Related links:

- HR 5538: Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017

- Rep. Hudson’s no-fly amendment

- Grist: “Congressman wants EPA officials on the no-fly list”

- The Guardian: “Honduras confirms murder of another member of Berta Cáceres’s activist group”

- About John Gorrie’s refridgerator

- Smithsonian: “Chilly Reception: Dr. John Gorrie found the competition all fired up when he tried to market his ice-making machine”

- Willis Carrier, designer of the air conditioner

- VICE: “As the World Prospers, More People are Getting Air Conditioning – And That’s Really Bad for the Climate”

- Percentage of US homes with air conditioning from 1979 to 2003

[MUSIC: Bob Marley, “One Love (dub version),” One World, Island Records, licensed from PolyGram Special Markets by Putumayo]

The Whistling Caribbean

Scientists have found that a current in the Caribbean Sea reverberates to make a “whistle”. (Photo: Sushant Jadhav, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sailors grow misty-eyed, dreaming of the song of the sea, but many folks see that description as merely a charming metaphor. But now science has caught up with art and reports that, yes, the sea does sing in a way – and it sings a very deep A-flat. Researchers at the UK’s National Oceanographic Centre in Liverpool have recently discovered that a cyclical pattern of water flow in the Caribbean Sea resonates in a way that can be detected from outer space. Researcher Joanne Williams is part of the Liverpool team looking at this phenomenon and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WILLIAMS: Hello.

CURWOOD: So, your team is looking into this cyclical pattern of water flow in the Caribbean that makes a whistle. Please explain to me, what are the mechanics of how a whistle would work here.

WILLIAMS: OK. So, in a whistle that you blow down as an instrument, you've got a current of air going through the whistle and it resonates with the frequency that fits nicely in that size of instrument and that's the sort of thing that we've got going on the Caribbean. So we've got a current of water, the Caribbean current, going right through the basin, and the wavelength that fits nicely in that basin just happens to be the right wavelength that also likes to resonate at that latitude in the ocean. So it's the Rossby wavelength.

A still from a video showing how the wave propagates (Photo: University of Liverpool)

CURWOOD: So, tell me what is a Rossby wave, and how is this different from any other kind of wave?

WILLIAMS: So, a Rossby wave is a very low frequency wave that you can get anywhere in the oceans, and what you have to understand is that you get very high frequency waves, the sort of thing, if you stand on the beach, you can watch the surfers, and they are coming in every couple of minutes, and then you get these very, very low frequency things that take days or months to cross the ocean. And Rossby waves are a particular wavelength according to the latitude in the ocean. And at the Caribbean, it would take about 120 days to cross the Caribbean basin which is 1,000 kilometers.

CURWOOD: So, these are called Rossby waves. Who is Rossby?

WILLIAMS: Rossby was an early 20th century scientist who studied waves in the atmosphere on Earth. But those studies also applied to the ocean.

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a listen to this wave, except I guess we can't really hear the wave itself because, how low in frequency is it? Remind me, please.

WILLIAMS: It's about 30 octaves below what you would find on a piano. So nothing can hear this.

CURWOOD: Not even very Barry White's voice is going to get down there, I guess, huh?

WILLIAMS: Not even Barry White. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a listen to the sound as it is sped up how many times?

Cartagena, Colombia, one of the places most seriously threatened by sea level rise in the Caribbean (Photo: Igvir, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Two to the power of 32.

CURWOOD: That's a big speed up. [LAUGHS]

[SOUNDS OF THE WAVE]

CURWOOD: So, in musical terms, what key is this whistle in?

WILLIAMS: So, this whistle...It plays A-flat. But it's an A-flat, 31 octaves below what you can hear. It's very, very low indeed.

CURWOOD: Now, when an orchestra plays an A, it’s very nice. When it goes down, when it flats down to an A-flat, it really warms things up. So we have a warm wave here.

WILLIAMS: [LAUGHS] You could call it that, suitable for the Caribbean.

CURWOOD: So, where else might you find this on the planet?

WILLIAMS: So, you might see it in other enclosed seas, but the particular thing with the Caribbean is that it's just exactly the right length to fit in the Rossby wavelength. So you get a lovely resonance there, an echo chamber, if you'd like.

CURWOOD: So, of course, when you say this can be heard from space, you need air to actually hear things. So this is a metaphorical thing that you're saying about it being heard from space.

WILLIAMS: Absolutely, yeah, and what we're actually recording from space is, the satellite uses radar to bounce off the sea surface and measure the height of the sea surface, and it's called “satellite altimetry.” It passes over a particular point in the ocean about every 20 days, and, as the Earth turns underneath, it passes over every point in the ocean.

Joanne Williams (Photo: UK National Oceanographic Centre)

CURWOOD: How high is this wave?

WILLIAMS: It's only a few centimeters, a few inches if you'd like. Down in the Caribbean, they haven't got very big tides, so it's big enough to show up.

CURWOOD: So, how do these findings inform our understanding of sea level rise, especially in terms of coastal communities? And of course we’re concerned about sea level rise with our changing climate.

WILLIAMS: Absolutely. What this will help us do is take out one of those signals from the sea level records. The more signals you understand, if you can take those out of the record, then what's left, it's easier to fetch trends and understand what's going on with the long term rise and also to make predictions of what you might see over the next couple of years and whether, for example, one of the peaks in this wave might coincide with other peaks and cause a particular flooding incident. When you find a strange signal in an old dataset it's really nice to know where it comes from. It's very reassuring when you find that it fits in nicely with all the ocean physics that you understand already.

CURWOOD: Joanne Williams is with the National Oceanography Center based in Liverpool, England. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today thank you very much and may the wave be with you.

WILLIAMS: [LAUGHS] OK, goodbye.

Related links:

- Watch and listen to the Caribbean Sea’s Rossby wave, sped up to the audible range

- RT News: “Caribbean Sea emits mysterious noise which can be ‘heard’ from space”

- About Joanne Williams

When Mother is a Hungry Bear

The mother polar bear has been wounded on her forearm (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Off to a much colder sea now, the chilly Hudson Strait off Canada. There you’ll find Akpatok Island and its many Polar Bears. They come there to hunt the large colony of seabirds called Thick-billed Murre; to steal eggs when they can, or to take the chicks on their first flight if they fail to reach the sea. But as our Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender observed, eggs and chicks are only snacks for a hungry polar bear. And by now, some bruins have been through so much with nursing and protecting their cubs that they’re down to their last reserves.

Bear, Walking

Akpatok Island

Hudson Strait

© Mark Seth Lender

All Rights reserved

LENDER: Left front, left back

Right front, right back,

Shluf, shlef, shluff, shliff,

She lifts –

As she sniffs –

Thick-billed murre fly low over the sea (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

SNAAAAAAhhh! –

Looks behind, looks ahead

As she -

Shliff, shleff, shliff, shluff

And on, along, the sand…

And all above her the limestone cliffs of Akpatok two hundred fifty meters tall (artifact of an ancient continental thrust); cascading toward the beach the cone-shaped talus mounds (hourglass of an ancient tearing down). She is young beside the land, young among polar bears.

Inside herself, inside the place she knows, Polar Bear is growing old.

The polar bear stretches out on the snow (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Shoulders pointed, hips narrow, and low; she does not, cannot hurry. Nor is there need. She cranes her scrawny neck that was thick and muscled as a hundred-season oak, her black snout pointing, searching, singling out (a thing that only she can see).

She stops –

- And stares:

The cubs that nursed her substance away in the frozen snow cave and for all that self-consuming time prowling the land are gone without a trace (except for the diminished state of her).

Does she think of them now, reminded by her stapled gate, a forearm that cannot lift or lengthen with natural ease? The bloody puncture marks where his teeth sank deep; the dark patch on her shoulder raked by claws when she fought for them…

These are readily visible signs. As to what she feels? Thinks? Imagines of her past and future self? The absence? Like the turned face among the crowd, but only the movement is caught; the thoughts, the pain at living lost in the silence.

The polar bear walks towards the icebergs (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

She lies down, the wounded limb stretched out upon a last remaining patch of snow.

Seven, thick-billed murre row past, their little wings against the wind. Between their path and the polar bear the water drifts blue to green as it shallows along the shore. The sky is untempered in its clarity and not a single cloud. The flood tide rolls beneath the omnipresent sun of these longest Arctic days, this shortest time of Arctic year...

And the lingering scent of cold always pervades.

She rises, and continues toward the distant headland where the last blue icebergs are marooned, both polar bear and ice diminishing into the inexorable paradox that Being becomes Non-being.

CURWOOD: Mark took photos of this bear – and her habitat – you’ll find them at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- More of Mark Seth Lender’s photography

- Adventure Canada

- Parks Canada

[MUSIC: Count Basie Orchestra, “After Supper (1994 Remastered Version),” The Complete Atomic Basie, Neal Hefti, Parlophone Records Ltd, a Warner Music Group Company]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes fom the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth