August 18, 2017

Air Date: August 18, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

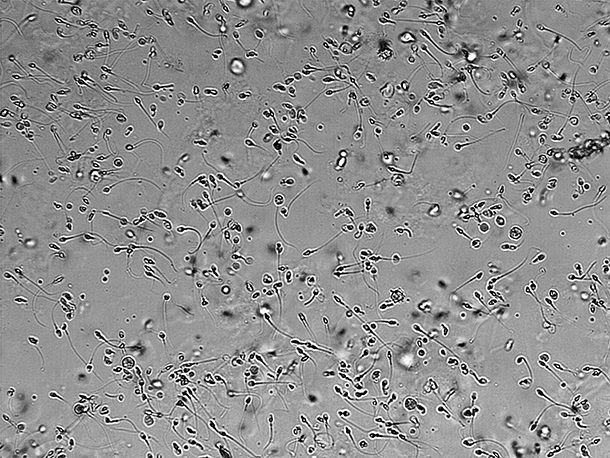

Chemicals Reduce Sperm Counts

View the page for this story

Fifteen years ago, over half of potential sperm donors in Hunan Province, China, met quality standards. Now, only 18% do, a decline blamed on endocrine disrupting chemicals. Host Steve Curwood discusses the implications of this new study with epidemiologist Shanna Swan, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. (10:46)

Freshening China’s Fish Farms

/ Jocelyn FordView the page for this story

Consumer demand in both the U.S. and China for safe and healthy farmed fish is shaping aquaculture practices in the world’s most populous country. And fish farmers are using traditional Chinese medicine as well as high-tech monitoring systems as they strive to keep their fish healthy and their farming practices transparent. Jocelyn Ford reports from the Hainan Province. (18:07)

BirdNote: Thieving Frigatebirds

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Some seabirds are brilliant at catching fish, but as Mary McCann explains, blue-footed boobies need to watch out for hungry thieving Frigatebirds. (02:03)

Golden Gobi Grizzlies

View the page for this story

Just a few dozen grizzly bears with bright yellow coats live in the forbidding Gobi Desert in Mongolia. Living On Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with writer and wildlife biologist Douglas Chadwick -- who has returned to the Gobi desert season after season to track these astonishing bears -- about how they survive and what can be done to better protect them. (12:20)

Polar Bear Summits Talus Mound

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Up in the arctic north of Canada’s Akpatok Island, a large, male polar bear climbs crags in search of murre fledglings, but instead finds a plane full of sightseers rounding the bluff, surprising each other. Writer Mark Seth Lender reports from the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. (03:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Shanna Swan, Douglas Chadwick

REPORTERS: Jocelyn Ford, Mary McCann, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI – it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. How chemicals that disrupt the hormone system can reduce fertility and more.

SWAN: Those men who have poor reproduction function, say low sperm count – several studies have now shown that their overall mortality is higher. In other words, they will die earlier.

CURWOOD: The dangers endocrine disruptors pose for men’s health. Also, fish farms in China aim to clean up their operations and reassure consumers in both the U.S. and at home:

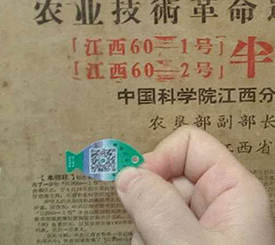

KUMAR: Put a camera into the farm area. A customer buys a bag of fish – you have a QR code on the bag. Run your smartphone through our QR code on the bag. And you will have a chance to see the actual farm that raised this fish in your bag.

CURWOOD: How both high-tech and traditional practices could make farmed fish safer.

Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Chemicals Reduce Sperm Counts

Human sperm counts continue to decline, says a new study. (Photo: Doruk Salancı, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

More than a half century ago, Rachel Carson sounded the alarm about the effects that a chemical could have on reproduction – in Silent Spring she was concerned about DDT’s impact on thinning the eggs of birds such as eagles and brown pelicans.

Well, today researchers in Taiwan are sounding the alarm about chemicals that are sharply reducing human sperm counts there. These chemicals are known as endocrine disruptors, and they can mimic or interfere with the natural hormones that control growth and a body’s immune system, neurological functioning, and fertility. Studies from Denmark a quarter century ago showed that sperm counts had declined by about a half from a generation earlier. Now the Taiwanese team has found that semen quantity and quality sampled from sperm donors have deteriorated even more in recent years, a change that is linked to endocrine disrupting chemicals. Epidemiologist Shanna Swan says these chemicals are everywhere.

Mounting evidence suggests there is a link between endocrine disrupting chemicals and the continuing decline in male fertility and reproductive health in different countries around the world. (Photo: Stephane Moussie, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

SWAN: Chemicals that make plastics soft, which are phthalates or chemicals that make plastics hard like Bisphenol A, or chemicals that are flame retardants, chemicals that are in Teflon, and so on, pesticides. Many, many classes of chemicals that are in our daily lives all the time.

CURWOOD: Dr. Swan studies endocrine disruptors and their effects at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. And years ago I talked with her about the Danish semen quality studies so I called her up again to relate the new study from China to the earlier research.

SWAN: So, the study you talked about from many years ago was a study, actually 25 years ago, 1992, by Elizabeth Carlsen who was working with Niels Skakkebaek and that was a -- I would say -- a landmark study. And what they said in that study was that sperm counts had declined 50 percent in the 50 years prior to that study, and this was pretty dramatic. There was nothing said about the cause of that decline at that time, but just that this was a considerable concern. Now, 25 years later, we're seeing that this has not gone away despite all the arguments to the contrary -- people who had not accepted that initial finding. And we are still asking why, but we have increasing evidence that chemicals in the environment play a significant part in that decline, if not producing it.

CURWOOD: And just how much of a reduction is this Taiwanese study suggesting we're experiencing now?

SWAN: Well, the Taiwanese study, I believe, said that something like only 20 percent of men who were previously suitable for their sperm donor bank would make it in now. There's a similar study actually from Israel that found almost the same numbers. And, because you have to keep the quality high to bring people in for assisted reproduction, if the quality is going down, and we see the quality going down because the WHO standards for western normal sperm has gotten lower and lower over the years … So, I would say it's probably not just China or Israel or Denmark ... it's probably many places in the world, although probably not all. And it's probably not equally a problem in all countries in the world, but it is a problem.

Male reproductive health can be compromised both in utero -- a permanent change, involving the structure of the reproductive organs – as well as in adulthood, when sperm quality and quantity can be impacted by various factors. (Photo: Carol Lara, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what do you think the odds are that it's affecting the quality of sperm here in the United States.

SWAN: I think that's … it’s pretty certain that semen quality has gone down in the United States. We have many U.S. studies. I personally have been involved in several of them. I would say we have very good evidence that male reproductive health, not just semen quality by the way, is in trouble, and this has consequences, not just for the ability to have a child, but it also impacts the health of the man. So, I think this is like a “canary in the coal mine,” that it's indicating there is a problem with male health, focusing on reproductive health but having impacts on the entire health of the male.

CURWOOD: What problems are you thinking of?

SWAN: Well, the immediately related problems are those that are linked to the function of the testes. There's a lot of evidence now that, when the male is in utero, the development of the testes governs a lot of what happens in the reproductive tract, and when you have problems with that testicular development, you can get in a whole array of things which have been called now the Testicular Disgenesis Syndrome. It includes low sperm count, infertility, testicular cancer, and various general defects. One of them is undescended testicles, another one is a condition where the opening of the urethera is not where it should be, and all of these have to do with the development of the testes at the right time in pregnancy, which requires the right amount of testosterone. So they're all linked to interference with testosterone production, which is a hormone produced by the endocrine system, and which can be disrupted by endocrine disruptors. So it kind of ties all together. Those men who have poor reproductive function, say low sperm count, several studies have now shown that their overall mortality is higher. In other words, they will die earlier.

CURWOOD: What's the evidence that chemicals are causing this?

Common household items including Teflon-coated pots and pans and sunscreens can contain endocrine disruptors. (Photo: Your Best Digs, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

SWAN: So, that's really a great question and one that I and many, many, many people are looking at. So, you can interfere in two ways. You can interfere with the development in utero, which is a permanent change. You can interfere with the adult function, which is a transient, a temporary, change. So, for example, there's a famous story of men who were growing pineapples in Hawaii and in Israel, using a chemical pesticide called DBCP, Dibromochloropropane, and it turned out, when the wives got together and talked about it, they were not getting pregnant. When the men were tested, they had no sperm. Zero sperm. Azoospermia. OK? Very severe adult interference, OK? They were taken off that job. The chemical was taken away, and their sperm function came back gradually, and after a while, it was restored. So, that's a pesticide that interferes with sperm function in adulthood. Lead does that. X-ray does that. Many chemicals can interfere at high doses to adult function.

CURWOOD: What do you think we've seen in terms of regulatory action to clean up these chemicals in our environment?

SWAN: I'm somewhat encouraged by the fact that levels of the phthalates that we were most concerned about and wrote about in 2005, those chemicals have gone down in the urine of pregnant women, about 50 percent, which is really, really encouraging.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

SWAN: Which means that there was some government action, although not for exposure to pregnancy. It was for children's toys, but OK. There was some government action. There was a lot of consumer concern, and I'm sure many manufacturers took the steps to reduce these chemicals in their products. So, that is excellent.

Plastics in many children’s toys contain Bisphenol A, to make them hard; and/or phthalates, to make them soft. Both of these chemicals are endocrine disruptors. (Photo: Chris Bickham, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

The downside is that, for these chemicals, these phthalates and also for Bisphenol A, as those things have been taken out, you buy something “Bisphenol-free,” then it's going to have Bisphenol F and Bisphenol S, which are substitutes, which now we learn have similar action to Bisphenol A. And we see that with substitutes for phthalates too.

So, it's kind of a, you know, it's a moving target. So, we say, “OK, we'll show you that these things are harmful,” and we do that, and we convince people to take them out of products, and then there are substitutes are put in which are not tested. So, I'd say the progress has been very slow, but not negligent. We have made progress.

CURWOOD: So, what can people do on their own, then, to reduce exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals?

SWAN: I'll tell you a few things. One problem is, though, that they’re more expensive. So if I say, “Eat organic. Eat unprocessed food,” there are segments of the population that can't do that. First of all, they might not have fresh food nearby. They might not have the money to pay for organic food, which is always more expensive. So, I can say, “Yes, I would recommend eating organic, eating unprocessed food, because processing does introduce endocrine disruptors into food. We know that.” Ideally, you would go to a farmer's market. You would buy organic produce. You would cook it yourself, and you would eat it right away. You wouldn't store in plastic. You wouldn't ship in plastic, and so on.

By the way, looking at the recycling codes on the bottoms of bottles and products in your house, there's a helpful thing that says, “Four, five, one, and two, all the rest are bad for you”, it has to do with the recycling codes. So, recycling codes four, five, one and two certainly not as bad as the others. You would be careful about what you put on your body, the sunscreens, the personal care products all contain endocrine disruptors. If you weren't sure, I would say, you go to Environmental Working Group's website and put in a product, and they will tell you how many endocrine disruptors there are in there and which ones are preferable. And I do that, and I recommend it to my kids and my students.

I would say, I don't cook in Teflon. I try to look at the chemical burdens of products that come into my home, and to the extent that we are told about these – You can't, by the way, on a can, see the phthalates that are in the product. You won't know that. So that's very difficult. That's why I'm saying you should eat unprocessed foods to the extent possible.

Dr. Shanna Swan is an epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. (Photo: Dr. Shanna Swan)

CURWOOD: Dr. Swan, how scary is all of this, this rather precipitous drop in sperm counts, the other effects of chemicals on our endocrine systems. Just how much trouble are we in?

SWAN: I personally think it's a very serious problem, which is why I've spent the last 20 years trying to understand it and help people minimize it. I think that it's one of the major challenges that we are facing as a society, and it's something that people are not taking seriously enough.

CURWOOD: Shanna Swan is a Professor of Environmental Medicine and Public Health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Dr. Swan.

SWAN: It was a pleasure, Steve. Nice to talk to you again.

Related links:

- China Post: Sperm count among male donors in Taiwan on the decline: study

- Environmental Working Group list of endocrine disruptors

- Our 2015 conversation with Shanna Swan on phthalates and hormone disruption

- LOE: “Hormone Disruptors Linked to Genital Changes and Sexual Preference”

- NYTimes: “Are Your Sperm in Trouble?”

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E9b-3Anffrw Layne Redmond, “Seven Heaven,” on Invoking the Muse, self-published by Layne Redmond]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Using traditional Chinese medicine – to make farmed fish healthier. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER1: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ron Block, “What Wondrous Love Is This” on Walking Song, traditional Appalachian, Rounder Records]

Freshening China’s Fish Farms

Harvesting tilapia for export on an internationally certified farm (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. If you buy fish sticks or tilapia filets, chances are they came from fish grown on a farm in China. But the rising middle class in China and the hunger in America for quick and convenient fish products have led to practices that can be unhealthy for both humans and the natural environment.

Aquaculture dates back thousands of years in China, but surging demand has led in some cases to pollution and the overuse of antibiotics. We sent Beijing-based reporter Jocelyn Ford to the island of Hainan, a major base of aquaculture in South China, where fish farmers are using everything from high tech to traditional medicine to clean up their industry.

[NEW DORY MUSIC, “FINDING DORY (MAIN TITLE)” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-n0699l7Ts 2AMBI DORY OPEN OCEAN https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rKjxJqIQTsE]

CURWOOD: But first she took a detour to Hollywood—

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: which recently has been enjoying a boom in animated fish.

[MUSIC]

DORY: Wait wait, no, I know where my parents are, they’re in... um, uh, what's it called? The place -- Soap ’N Lotion?

OTHERS: Open ocean.

DORY: Open Ocean!

OTHER: Open ocean! I know where that is!

FORD: Ah, the romance of colorful fish swimming freely in the wide open ocean! In the Disney version, the heroine is Dory. She triumphs when she escapes from human captivity, and swims back to her parents. But in the real world, it is the captive fish that are heroes, the fish on fish farms. They're saving the wild fish.

HAN HAN: With such a huge population in China, if we didn't have the aquaculture, if we totally relied on the wild fishery. I guess we would already running out of all these wild fish, maybe 10 or 20 years ago.

Fishing boats on Hainan. China relies on aquaculture for most of its seafood (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

FORD: That's Han Han, the founder of the China Blue Sustainability Institute, China's first non-governmental, environmental organization focused on sustainable fishing and aquaculture. Today, aquaculture accounts for one of every two fish that land on the dinner table worldwide, and it's growing faster than other sources of animal protein. China is the global aquaculture leader, and because of its expertise here, it wants to help other countries. Fisheries Bureau Deputy Director General, Li Shumin says...

LI SHUMIN [translated with voiceover]: We have many good aquaculture technologies that we would like to share with other developing countries because we know that fishing is not going to be sustainable.

FORD: Aquaculture is expanding globally at about five percent a year, and that’s a plus for some of the Earth's most pressing environmental issues. For example, compared to a pound of beef, a pound of fish has only about one-seventh of the carbon footprint. But large-scale aquaculture has created new problems. Naturally, farmed fish need to eat. And gone are the days when Chinese fish farms were all organic. Qi Genliu is a professor at Shanghai Ocean University.

QI: Traditionally we used grass to culture grass carp.

FORD: That changed with the growth of the fish feed industry and the need to feed carnivorous marine fish.

QI: Now we use feeds. It will not only more efficient, but it will also save labor.

Waste water is released untreated into the ocean at this hatchery in Hainan (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

FORD: About a quarter of global wild fish catch is used for fishmeal or fish oil. So now many of the so-called “trash fish,” which include anchovies and the young of other species, are being overfished. Then, there’s the problem of water quality. In China, many farmers overstock their ponds, and don’t properly clean the water. Fish get sick. The farmers dump in antibiotics. Again, Han Han, of the China Blue Sustainability Institute.

HAN HAN: We can produce all this seafood in such a low cost. It is because we have been industrialized to produce them in a massive scale. That can lower your new unit cost, but you didn't take into account the massive pollution.

[CAR DOOR, TAXI DISCO MUSIC]

FORD: Hop into a taxi, drive around 90 minutes from Han Han's office, and you reach Wenchang. This is the capital of fish farming on China's tropical southern island of Hainan. The roads are lined with coconut palms and artificial ponds. There are square ponds the size of several volleyball courts, and oblong ones as big as soccer fields. Fan Qingwei is a sea cucumber production manager. He agreed to give me an unauthorized tour of his former hatchery.

[FOOTSTEPS AND WATER TANK]

FORD: What’s this?

FAN: Sea cucumber.

FORD: Is that one of your babies?

FAN: Yeah.

FORD: It’s cute, it’s slimy.

FORD: Fan Qingwei’s claim to fame. Last year he bred one-and-a-half million baby sea cucumbers, a Chinese delicacy that is said to have health benefits. He takes me to the beach, a stone’s throw beyond the hatchery’s ponds.

The sea cucumber is a Chinese delicacy (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

[WAVES, WALKING ON BEACH]

FAN: The water pour out the pipe, here.

FORD: Let me go take a look. Oh, there's a crab!

FORD: The hatchery is a few hundred feet from the ocean. Technically that's a violation of recent regulations. The water is discharged without treatment.

FORD: So the water's really sort of murky and brown and foamy. Not great quality, huh?

FAN: Yeah, not great quality.

FORD: Depending on who you talk to, there are hundreds or thousands of such farms. Many are small, family-owned factories that operate under the radar screen. They release water back into the sea that is contaminated with fish waste, as well as left over fish feed and medicines such as antibiotics. The concoction is like a witches brew. It worries some experts such as Cai Yan.

CAI YAN: Antibiotics kill a lot of bacteria. So they reduce the diversity of microbes in the environment.

FORD: Professor Cai Yan is an aquaculture researcher at Hainan University.

CAI YAN: You actually resulted in more super bacteria that you can't do anything with them. You know, you can't kill them. So if these bacteria, these super bacterias, go into the human system. OK, one day you get sick, you don't have any medicines to kill it. That is the big worry.

FORD: While Professor Cai Yan says there are no known cases in Hainan of humans getting sick from super bacteria, marine technician Fan Qingwei says, fish farmers are having problems. Medicines they once used when fish fell ill are no longer effective. Some farmers have seen big die-offs.

FAN [translated with voiceover]: The damaged environment has already hurt their profits.

FORD: The government has taken action. It's banned the carcinogenic antibiotics, and in Wenchang created a fund for a water treatment plant. The idea is that all the farmers could send their dirty water through the plant before it returns to the ocean. But with so many small operations, the project would be both costly and complicated. And it’s unclear if it’ll get off the ground.

The beaches and mild climate of the island of Hainan make it a popular destination for vacationers from China and abroad as well providing favorable conditions for fish farmers. (Photo: Thomas Fischler, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

There also aren't enough inspectors to police every farm. But my visit to Fan Qingwei's hatchery suggests some government scare tactics are having an impact on reducing the use of antibiotics.

[SOUNDS VIDEO GAME]

It's lunch break. 30-year-old worker Huang Defu, in charge of shellfish at the hatchery, is busy with his cell phone.

FAN: He's playing the game in the cell phone.

FORD: Wait for him to finish his game.

[SOUNDS OF VIDEO GAME]

FORD: The conversation turns to recent, high-profile arrests of fish farmers.

FAN [translated with voiceover]: The government tests the fish. If they find you using illegal antibiotics, they might put you in jail.

FORD: So, the boss has ordered Huang Defu to use, instead, probiotics, the kind of good bacteria that's found, for example, in yogurt. Across the ocean, health-conscious consumers in America are also helping make farming practices here in China safer and more environmentally friendly.

[COMMERCIAL JINGLE: “Trust the Gorton Fisherman”]

FORD: China is the largest single exporter of tilapia to the U.S. 95 percent of tilapia farmed on Hainan ends up on U.S. store shelves, much of it as filets or fishsticks. So when a couple of years ago some of China's fish shipments to the U.S. were rejected due to unsafe antibiotics, exports took a hit. Companies like Gorton’s try to reassure consumers with generic pledges on their website. But regaining trust isn’t as simple as singing a jingle. Han Xuefeng heads the two-year-old Hainan Tilapia Sustainability Alliance. He says for the Tilapia industry, boosting quality is a matter of life or death.

HAN [translated with voiceover]: Since prices fell in 2014, we've felt we are on the brink of a crisis.

FORD: A number of small farmers and processing plants have gone out of business. Others are teetering. But the Chinese character for "crisis," weiji, also means “opportunity.”

HAN [translated with voiceover]: What we need to do now is to find out how to promote sustainable production in order to make use of the opportunity. We’ve already worked hard to make many people in the industry realize the importance of sustainability.

Zhang Meiyu feeds the fish she raises with Chinese herbal medicine techniques (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

FORD: Han Xuefeng's association has found a partner in the island's most important export market. Two years ago, The Fishin’ Company, America's largest tilapia importer, stepped up to the plate.

[VIDEO SOUND TRACK with man's voice "I should not be here, actually, right? But the reason I'm here, is..."]

FORD: The founder and president of The Fishin’ Company, Manish Kumar, started coming to Hainan to build a coalition for a safer, more environmentally sound and sustainable tilapia industry. His company is sponsoring trainings, and offering financial incentives to a few model farms that invest in improvements. The idea is, others will follow suit if they see it makes financial sense. Many of the small fish farmers have no prior professional training. So the Fishin’ Company starts with simple things, like helping farmers keep records. They track weather conditions and water temperature, which affect fish health. And the farmers keep records of the feed and the medicine they use. The plan is to help more farmers get international certification by third parties. It's a brave, bold move for the industry leader and a contrast to Manish Kumar's diffident demeanor.

KUMAR: Hey Jocelyn, I haven't probably warned you, but I'm extremely nervous, uh...

FORD: Am I scary?

KUMAR: Not at all...

FORD: As America's largest tilapia importer and the supplier for Walmart, Manish Kumar has a lot at stake.

KUMAR: I'm gambling for the future prosperity of this industry, which has given me so much, which is my career, and I'm gambling against losing my reputation. And I'm gambling very hard for positive change.

Fish in Zhang Meiyu’s aquaculture ponds (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

FORD: His ideas include increasing omega-3 levels in the tilapia, the fish oil that may help lower risk of heart disease, cancer and arthritis. To help reassure customers who are nervous about what their fish are eating, next year he's planning a state of the art oversight system that involves cameras, QR codes, and consumer monitoring.

KUMAR: We will now proceed to do something no one in the industry has done before. Put a camera system into the farm area. A customer buys a bag of fish. You have a QR code on the bag. Run your smartphone through our QR code on the bag, and you will have a chance to see the actual farm that raised this fish in your bag. And how it's being raised.

FORD: Customers can see the type of feed, and the plant where the feed was made, and the insomniacs can watch the fish grow 24/7. Manish Kumar says the extra cost will be negligible. As the largest supplier of tilapia, he expects to be able to take advantage of economies of scale.

A fish farmer participating in the Fishin’ Company’s training program. (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

KUMAR: I see, in the early part of next year, us having the ability to, through our packaging, give customers who have any, even a shred of doubt, feel better about what they are buying from us. And, I challenge the rest of the industry to do it. And then the people who don't do it will be the ones on the hot seat.

FORD: Meantime, the picture is different for Chinese consumers. They have more reason to be concerned about food safety than Americans. As of today, Chinese consumers don't have much of an appetite for frozen tilapia. Many prefer to purchase their fish live rather than frozen, but they are increasingly concerned about what goes into their food, and Han Xuefeng of the Hainan Sustainable Tilapia Alliance sees that as an opportunity.

[SPEECH BY MOTIVATIONAL SPEAKER FOLLOWED BY APPLAUSE]

FORD: On this day Han Xuefeng and his staff attended a lecture on how to build a brand. He thinks, as an island, Hainan can profit from the argument that its water is less polluted than water in other parts of China where Tilapia is farmed.

HAN [translated with voiceover]: We're at a turning point. Before Chinese were only concerned about how to get enough food to eat. Now they want it to taste good and be healthy and safe.

FORD: Meanwhile, some erstwhile consumers are taking matters into their own hands, by producing fish they can trust.

[SOUND OF BEATING THE SIDE OF A TANK]

FORD: Not far from the sea cucumber hatchery, Zhang Meiyu is signaling to her fish that it’s feeding time.

[SOUND OF BEATING THE SIDE OF A TANK]

FORD: She is improbably dressed in high heels, tight white pants, and a fashionable gray tunic, and she’s wearing blue eyeshadow. Zhang beats the side of the tank and a large mob of fish swarm toward her.

FORD: What kind of fish?

ZHANG [in Chinese]: Zhege shi longban.

FAN: Grouper.

FORD: Just over a year ago, Zhang vacationed on Hainan, known as China's Hawaii. Then, on the spur of the moment, she decided to buy an abandoned fish hatchery. Within a month she’d relocated to the island.

ZHANG [translated with voiceover]: I had been in business. I didn't understand fish. I'd never touched one. But I discovered all the farmed fish back home was frightening. Even if you give it to me, I won’t eat it.

A fish from a Beijing restaurant (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

FORD: Zhang had a dream. She wanted to have safe fish and create a brand that others could have confidence in. She believed she could do so by using a new version of an ancient practice: Chinese herbal medicine – but for fish.

ZHANG [translated with voiceover]: Everyone laughed at me and said I was crazy. They don’t trust Chinese herbal medicine.

FORD: Zhang Yumei is a pioneer in her neighborhood, but Chinese scientists have been researching how to farm fish using Chinese herbal medicine for many years. Dr. Guo Weiliang conducts experiments at Hainan University.

GUO [translated with voiceover]: After we notice the bad effects of antibiotics, and then we realized maybe we can do something else, for example these, Chinese herb things.

FORD: China has been using herbs for human treatment for thousands of years, and Dr. Guo is applying the know-how to fish, using western scientific techniques. The approach is preventative. The idea is to boost the immune system before the fish get sick.

[WATER TANK SOUNDS]

FORD: At the hatchery, Zhang had a steep learning curve. In the early days, she lost a lot of fish because she failed to recognize when they weren’t feeling well. Today, she’s proud of her results. In the last half year, she’s only had four deaths.

ZHANG [translated with voiceover]: When we discover the fish are about to get sick, we take action.

FORD: Zhang says the herbal treatment costs more than cheap antibiotics, but in the long run, she believes, she’ll come out ahead, and other farmers will want to copy her. Professor Guo says, however, it will be a while before cost of herbal treatments certified for fish will come down. For one, there are not enough researchers knowledgeable about fish, Chinese medicine and agriculture. And those that are, are likely to find more lucrative jobs. But the government is concerned about the quality of the fish, and the falling Tilapia exports.

[LI SHUMIN SPEAKING IN CHINESE]

FORD: Fisheries Bureau Deputy Director General, Li Shumin, says he’d like Americans to eat more tilapia, and he emphasizes that not only the government but also industry is now doing safety inspections before exporting to the U.S. At the end of the day, it may well be increasingly affluent and health-conscious Chinese consumers who start driving the change.

QR code from restaurant fish (Photo: Jocelyn Ford)

[RESTAURANT SOUNDS AND MUSIC]

FORD: Back in Beijing, at this Chairman Mao themed restaurant, an itinerant singer belts out songs for $7 a pop. My dinner party goes to a white-tiled fish tank as big as a queen-sized bed, to choose our dinner…live.

[SOUND OF FISH FLOPPING]

FORD: Our dinner has a tiny green fish-shaped tag on its fin, with a QR code.

So you just scanned it. And what does it tell us?

WOMAN: It’s just like a phone number who sold this fish. If you call the number, of course the person is going to tell you the fish is authentic. They sold this fish!

FORD: It's a gimmick. Like anyone could fake this, anyway.

WOMAN: Yeah, exactly, it’s not like a third party supervision, something.

FORD: But if Manish Kumar’s Fishin’ Company’s idea catches on of giving consumers 24-7 access to witness just how that fish got to their table, you can bet Chinese consumers will want the same thing for fish they put on their plates. And once that happens, the economies of scale would take over, and might make environmentally-friendly farmed-fish more affordable for all.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jocelyn Ford, in Beijing.

Related links:

- China Blue Sustainability Institute

- Stanford-led study says China's aquaculture sector can tip the balance in world fish supplies

- Hainan Tilapia Sustainability Alliance

- US FDA Import Alert pertaining to Chinese seafood

- Journal article on traditional Chinese medicine and fish immunity

- Hainan University (In Chinese)

- The Fishin' Company

BirdNote: Thieving Frigatebirds

A frigatebird attacks a seabird for its meal. (Photo: Neil Winkelmann)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: One of the most glorious sights of tropical oceans is the vision of the

Magnificent Frigatebird soaring over the waves. But as Mary McCann points out in today’s BirdNote, sometimes the way these fork-tailed creatures behave is – well, less than magnanimous.

http://birdnote.org/show/frigatebirds-kleptoparasitism

BirdNote®

Frigatebirds’ Kleptoparasitism

[Featured bird sound/audio]

MCCANN: Some birds are masters at catching fish. In the warmer regions of the world’s oceans, large seabirds called “boobies” plunge headfirst into the water, snatching fish in their dagger-shaped bills. But as a booby flies up from the waves with a fish now in its gullet, there may be another big seabird, a frigatebird, waiting overhead, with its eye on the booby and on the booby’s fresh catch.

[Red-footed Booby aggressive call, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/6036, .32-.33]

Airborne Frigatebird. (Photo: José Zayas)

Now begins one of nature’s great chase scenes. The booby flaps full throttle away from the frigatebird, but there’s no escaping. With a light body suspended on long, narrow wings and a long, scissor-like tail to match, the frigatebird is faster and more agile. It lopes up behind the frantic booby and with its long, slender, hooked bill, clamps onto the booby’s tail or wing-tip. Thus snagged in mid-air, the booby flails. A crash is imminent, unless it surrenders what the frigatebird wants. So it disgorges the fish it’s just captured. The frigatebird releases the booby and swiftly snatches the free-falling fish.

[Magnificent Frigatebird, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/136232, 0.04-.06]

Fortunately for boobies, frigatebirds don’t steal all their meals. Most of the time, they hunt their own seafood, perhaps a squid snapped from the ocean surface or a flying fish as it skims across the waves.

But now and again, when a chance comes up, they’ll take it.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Magnificent Frigatebird, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/136232, 0.04-.06]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

6036 recorded by Robert J. Shallenberger and 136232 recorded by Martha J. Fischer.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org March 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

Video of frigatebird kleptoparasitism: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifes66o4t7s

Another good source is http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Fregatidae/

http://birdnote.org/show/frigatebirds-kleptoparasitism

CURWOOD: And for photos, soar on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen on the BirdNote website

- More about Frigatebirds from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds

- Another BirdNote about Frigatebirds

[MUSIC: Cecil Payne Quartet, “Bosco,” Casbah, Cecil Payne, Stash Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Camels are common in deserts, but the Gobi desert of Mongolia has camels and grizzly bears…That’s ahead here on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Marcus Robert - Foggy Day - Album - Gershwin For Lovers (1994) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KG1vUC6--Jc]

Golden Gobi Grizzlies

A Gobi Grizzly negotiates a dry rocky slope (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Grizzly bears can be huge and fearsome beasts, not to be messed with when you're out in wild country. Their range extends across western North America – and through much of Asia. There’s even a tiny population of grizzly bears that roams the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, notable for their shocking coats of bright gold fur. Wildlife biologist and writer Douglas Chadwick spent many seasons with a team traveling in the Gobi to photograph and learn more about these creatures that seem to defy all odds. He’s the author of Tracking Gobi Grizzlies, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

CHADWICK: Thank you. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: Hey, tell me about your fascination with Grizzly bears. In your book you explain that your interest in Grizzlies began way before you arrived in the Gobi. What sparked that fascination?

CHADWICK: Well, I was like most people, Steve. I knew of the stories. I knew the “There I Was” movies, the little pioneer girl getting chased by the big bear. I carried a big .44 Magnum on my hip and worried a lot when I first started hiking in bear country. And one day I watched three bears. It was a mother sliding down a snow bank in the summer. It was a hot afternoon. I had been doing the same thing. And then she went back up to the top of the snow-bank and put her two cubs on her lap and slid down on her back with them, and then they went up and did it again. And this went on for about 20 minutes and by the end of that I said, “I like these people. I want to know more about them. I don't think the stories and everything I've been told has given me any kind of reasonable picture of one of the master mammals out here with me.”

Douglas Chadwick chronicles his desert adventures in his new book, “Tracking Gobi Grizzlies: Surviving Beyond the Back of Beyond.” (Photo: Elena Meredith)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now, how did you learn that there was a population of Grizzly bears living in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia? I mean, this is, you know, a lot of rocks and expansive deserts, not a place that I think of Grizzlies.

CHADWICK: Not a place I would have thought of Grizzlies. And I was thinking about bears while I was hiking in northwestern Mongolia in the mountains in a place that looked a lot like Montana with forests and glaciers up above on the border of Russia and Kazakhstan. And I was tracking Snow Leopards on a story for National Geographic. And my translator, who’s a woman working for the Snow Leopard Trust, told me while we weren't seeing any Brown bears, which are the same as Grizzly bears, and I had expected we might because we were hot on the trail of Snow Leopards. There were ibex watching us from the cliffs as it was just that kind of place, but the bears had been pretty much shot out. And she happened to mention, “Well, we also got these other Grizzly bears in Mongolia.” And I said, "Where?" And she said, "In the Gobi Desert.” And I said, "We've got a communication problem. I thought you just told me there were Grizzly bears living in the Gobi Desert.” And she said, "My father happens to be the director of the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area, and he has studied them for 30 years.” And I said, “OK. Next question is, how many of these kinds of bears are there in Mongolia?” And she said, “About 30.” I said, “Now that's in Mongolia. How many are there?" and she said. “They're all in Mongolia and nowhere else. There are 30 Gobi Grizzly bears left in the world.”

CURWOOD: So, then you had to go! So, describe to me the first time you actually got to sight a Gobi Grizzly in the wild, and how did you react?

The front claws of a Gobi bear that move across that same rock terrain month after month. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CHADWICK: Well, it's small and lean compared to our North American Grizzly bears. It has wildly mussed up – I call it bed hair – sticking out all over the place and is very much a Grizzly. We would catch them in a box trap in order to place satellite radio collars on them. And yet even a tranquilized Gobi Grizzly, it was clear to me the power of the bear is the same as the ones we live with here, and certainly, as it came out of the drug, it started smashing up the trap and then proceeded to chase off a large van full of Mongolians and a couple of Americans that was five times its size. I said, “Yes, that's a Grizzly.”

But it smelled sweet. It smelled like dust. It smelled like plants that it had been digging. Its breath was warm. It had these stubby claws that said at a glance, “I have been walking on rocks all my life, and I have been digging through gravel to find roots, and I am a beat-up, thirsty, dusty bear on the outer edge of possibility, but I'm here.”

CURWOOD: So, why were you in the Gobi at that time, by the way?

CHADWICK: I had been invited to come down and join a research team of Americans and Mongolians, small group. I joined in 2011. I intended to just go over and learn about these bears and write about them based on one season. And the season is after they wake up in the spring and before June arrives because by then it's getting to be close to 100 [degrees] in the day, and any animal captured in a trap is the subject to heat stress. So we’d quit, and we’d go home.

The project leader and others go back again to the Gobi in the fall and just simply track the animals. But I went over for five springs in a row and spent a month there camped out, not sure where I was half the time, but camped out somewhere, where we could access three or four oases, set up traps there and then spend the day tracking them through the countryside, observing other wildlife, finding out these little details, like Gobi bears often drink from pools that have been dug by the wild asses with their sharp hoofs. So if you're not saving wild asses you may not be able to save Gobi bears.

CURWOOD: You mentioned that they're small. Why are they so small?

CHADWICK: It's pretty hard to get big on a diet of wild rhubarb, wild onions, lizards, beetles, occasionally scavenging the carcass of a larger animal, but everything is few and far between, both plants and animals. And that number I gave you, 30, is probably an underestimate. It looks as though there are three to possibly four dozen, and it also looks as though they have been increasing very slightly since the study started in 2005.

Gobi Bear Project leader Harry Reynolds (left) and Michael Proctor check the mouth of a captured male. Tooth pattern and sharpness are good indicators of a grizzly’s age, but in the Gobi, estimates are adjusted to account for wear and tear from gravel and sand when foraging for roots, insects, and burrowing rodents. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the harsh environment, the outdoor environment there in the Gobi. It’s so dissimilar from the ones where nearly every other Grizzly population is located. In the warm time of year, it could be, what, 120 degrees? And in the winter, it can be, what, minus 40, huh?

CHADWICK: It can be minus 40 with a heck of a wind coming off the Gobi Altai Mountains, and the bears do hibernate there, and their cycle is a lot like the one you’d find here with the bears in Montana in Glacier Park.

CURWOOD: So, Doug, there are just perhaps as many as three dozen, maybe four dozen of these bears. That's not many bears. Originally, how many would there have been there, and what happened?

CHADWICK: You know, it's a little like asking how many bison or how many Grizzlies used to be in North America. Nobody knows because we blew through them so quickly. And there are estimates, and that's all you can have. And look, Gobi bears were not discovered or proven to exist until 1943, and that's simply a tribute to the size of the Gobi and the difficulty of living there and the fact that it was still just barely beginning to be explored around the early 1900s, and the Gobi bear was a myth. It was like Bigfoot or Sasquatch or something. There was something big and hairy roaming around out there that occasionally walked on two legs. And so I can't give you the number of how many would've been around. I doubt it was in the thousands, but it might have been.

Harry Reynolds sedates a captured bear. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: I understand that the pilot conservation project helps the bears by feeding. How exactly do you feed a Grizzly?

CHADWICK: Well, first of all I spend a lot of time in Montana working with biologists and state and federal agency people going around telling people, “Please do not feed the bears.” And a fed bear is a dead bear because it learns to get food near humans and that's not a good strategy for staying alive. And suddenly I find myself not only in the back-of-beyond, riding around in a Russian-made van with a small herd of Mongols wondering what I'm doing, but we're going out to feed Grizzly bears.

And what you do is dump sacks of livestock chowder, or chow, into a big bin with a trough on the bottom and put it near the oasis. They don't depend on it, but there's a lot of drought years, and it's not getting any better in a warming, drying climate.

CURWOOD: Doug, how is the Mongolian government responding to these conservation efforts for the Gobi Grizzlies?

CHADWICK: The Mongolian government...The best way to say this is, in 2013, the Mongolian declared that the year of the Gobi bear, which they call Mazaalai. And there were, there's even a Mazaalai vodka you can buy, and there's Mazaalai bread. And they know about the golden Grizzlies of the Gobi Desert, and they want to preserve them. It's just that nobody had any... OK, we all want to save them. How? What do they need? What can be done? They've improved some of the water sources. They've got some solar-powered pumps that work. They've even tried cloud-seeding in the area. We work with University scientists from Mongolia. We've had the Minister of the Environment come down and join the team. They're more than willing to help.

Douglas Chadwick is a wildlife biologist and author with a love for grizzly bears. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: So, how well are these efforts going?

CHADWICK: Um, how it's going is the story I really wanted to tell, and that was the main incentive for the book. It’s on the upswing, and some of the happiest moments of my life have been standing out even in a duststorm and bitter cold winds, but checking the images on the automatic camera set up near the feeder. And as you scroll through them, all of a sudden there are two baby bears with their mom, so they are reproducing.

We're also finding more bears. The way you count them is...Obviously you're not going to cover an area five times the size of Yellowstone Park…but you can collect hair, and that count is going up by the year. So, it's very encouraging. And recently the Mongolian government just set aside a large reserve. It links this great Gobi Strictly Protected Area where all the last bears are, through this new reserve to Gobi Gurvan Saikhan, which means Three Jewels National Park. And that is a bit wetter. It's got more vegetation, and it is a former range of the bears. And if they can connect through there, back into that former range, I think they'll do well.

Really, this story isn't just about, how do you save a Gobi bear? It's, how could you turn your back once you know they're there? You have to help somehow. That's how I felt. But more importantly, it's, like, if we can pull this off, it says something about all those big animals out there, so many of which are at risk around the world.

CURWOOD: Douglas Chadwick is a wildlife biologist and author of "Tracking Gobi Grizzlies." Doug, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CHADWICK: Well, thank you so much for the time, and I don't know how else Gobi bears are ever going to be heard about or known by the rest of the world, and I'm glad for the opportunity. Thank you.

Related links:

- Tracking Gobi Grizzlies book website

- Douglas Chadwick for National Geographic: “Can World’s Rarest Bear Be Saved?”

- IUCN lists Grizzly bears as a whole as “Least Concern”, though some local populations are declining

- Douglas Chadwick’s National Geographic profile

[MUSIC: Childsplay, “Bob’s Child” on Twelve-Gated City, Matt Glaser, self-released by Childsplay]

Polar Bear Summits Talus Mound

Murre nest high up on rocky cliffs in the lower arctic region. Polar bears often climb in search of them for food. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: And we stay with bears for this next story. This time, it’s a different bear, of a color as different as night and day.

We’re up in the north of Canada, in Hudson Strait on the island of Akpatok, noted for its Polar bears, as well as 700 foot high limestone cliffs where the thick-billed murre nest. They’re a species of auk with stubby, penguin-like wings whose nests lure the great white bears who also live there. But as our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender observed, sometimes the bears seem to contemplate other potential sources of nourishment.

Bear on the Talus Mound © 2015 Mark Seth Lender All Rights Reserved.

LENDER: He is big and white and perfect. That kind of polar bear a certain kind of hunter wants to see, mounted on a wall. All things being equal, you can be certain, Bear’s the one bringing all the trophies home.

Two weeks and the fledgling thick-billed murre will begin to fall from their hard rock nests on Akpatok, in the sheer limestone wall. Unable to fly, they will tumble five, six, seven hundred feet straight down, aiming for water. Lucky for the ones who make it. The others? Manna in Feathers (that’s what Bear is waiting for).

Hudson Strait and Akpatok Island is one of the uninhabited Canadian Arctic islands in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And Bear no doubt is tired of waiting.

Up he goes walking the loose detritus of the talus mound, the slope steep as an avalanche though to Bear with his wide gripping feet the incline might as well be level ground. A hundred yards high, Bear sits down.

He looks about as if he’s enjoying the view. Though there is no view. Only the blank face of an ocean just as well admired from below. And with nothing to eat there is nothing for Bear to do. No reason for the climb, the calories burned, this particular place. No apparent cause for Bear’s demeanor, and that lolling lazy look on his face.

The Plane curls around the corner in close, wing high not more than thirty meters between the vertical of the cliff and the fuselage. Looking for polar bear but entering the space from the wrong side: They had no way of knowing Bear, was there.

Yet there he is. Right altitude right attitude to look, straight, into the little windows like seal holes in the ice, and the funny chewy little faces pressed against the Plexiglass. Nice. Very nice.

The murre are not there, but bear climbs anyway. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And the Rolls Royce engines hit the red line with a growl that even a polar bear cannot match and the airplane levels out again and vanishes at a couple of three hundred knots.

Bear does not run, though I’ve seen bigger ones than him take off like a shot with far less provocation. Instead, Bear lies down, his chin resting on those huge white paws like some guy stretched out on the couch.

Late in the afternoon the same plane makes another pass. Same approach. Same altitude. Same distance off the cliff.

Bear is not there.

There are no polar bears at all.

And I wonder, as they disappear into the clouds, all those paying customers and all the money they just spent, really: Who’s the entertainment?

CURWOOD: Our resident explorer Mark Seth Lender – and there are photos of this close encounters of the ursine kind at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- More about the common murre

- Akpatok Island is one of the uninhabited Canadian Arctic islands

- Mark reached Akpatok onboard ship with Adventure Canada

- Parks Canada

[MUSIC: David Bowie Eight Line Poem, Hunky Dory, 2015 Rykodisc]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Helen Palmer, Rebecca Redelmeier, Olivia Reardon Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger and Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth