September 21, 2018

Air Date: September 21, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Wastes Flood The Carolinas

View the page for this story

Heavy rains and floods from Hurricane Florence inundated North and South Carolina with hog and poultry manure, and also threaten the structural integrity of coal ash ponds loaded with toxic metals. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb spoke with Catawba Riverkeeper Sam Perkins about how weak regulations and lack of enforcement put public health at risk. (07:47)

Science Note: Hurricanes, Lizards and Leafblowers

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Hurricanes may act as a force of natural selection for Caribbean lizards, according to a recent study in the journal Nature. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman explains how scientists used leaf blowers to simulate hurricane-force winds to study how the hardiest lizards hang on. (02:10)

“Pa’lante”: Puerto Rican Resilience After Maria

View the page for this story

It’s been a year since Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, taking roughly 3,000 lives. Most the morbidity came not from the wind and rain of the hurricane itself, but rather from the isolation that followed. Cut off from the outside world, many people died from such conditions as treatable infections, unsafe water and accidental electrocution. But as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, some communities are looking at Hurricane Maria as a call to organize and become more resilient for future storms. (19:09)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss the extra hardships that the Gullah and Geechee people, who are descended from slaves and live off the coast of South Carolina, face in the wake of Hurricane Florence. Then, they note the dangers of an alternative to BPA and take a look at how the removals of major hydroelectric dams can help struggling fish populations recover. (04:11)

Women Climate Scientists Threatened and Harassed

View the page for this story

Climate scientists of all genders face harassment, bogus records requests, and even death threats. But women climate researchers are often subjected to sexist and misogynistic attacks as well. There are allegations climate-denying “lone wolves” and climate denial organizations may be linked to these efforts to silence climate scientists. Lauren Kurtz, the Executive Director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund, tells Host Bobby Bascomb about the kinds of harassment and threats her clients have faced and fought back against. (07:08)

An App For Urban Foraging

/ Savannah ChristiansenView the page for this story

The harvest season brings a bounty of edible foods, even in cities. An online map called Falling Fruit is using public datasets to guide foragers to food for the taking. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen reports. (05:51)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Lauren Kurtz, Sam Perkins

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I'm Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood

Hurricane Florence caused major flooding for industries, including hog farms, along the coast of the Carolinas.

PERKINS: Over the course of just over 2 years, we've now had 2 500-year events, and we've had catastrophic flooding. So, maybe this is not the best place to have a high density of so much animal waste.

BASCOMB: Also, on the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico we’ll share personal stories from survivors.

NIEVES: It was like all the moves that you’ve seen of Armageddon, of destruction, of the end of days. It was like, this is done. And the fact that the communication collapsed meant that we couldn’t hear the government but we couldn’t hear each other. All we had was the people next to us.

BASCOMB: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Wastes Flood The Carolinas

Homes surrounded by water flowing out of the Cape Fear River in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence. (Photo: North Carolina National Guard, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood is on assignment.

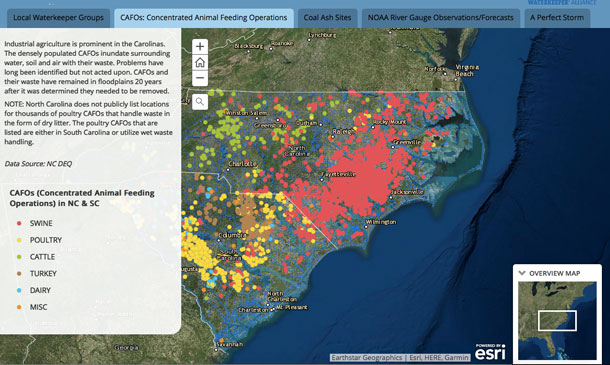

Coastal North Carolina is prone to flooding. Its many estuaries, deltas, and flood plains span a region often hit by hurricanes. It’s also home to many hog waste lagoons, coal ash storage facilities and superfund sites. Hurricane Florence recently dumped up to 30 inches of rain on parts of the coast, flushing bacteria-laden feces and toxic ash into local rivers. Here to tell us more is Sam Perkins, he’s the River Keeper for the Catawba River Keeper Foundation in North Carolina. He’s used GIS software to map the polluting industries sitting in the path of Hurricane Florence.

PERKINS: When you pull up the map, the first thing you will see is an outline of the river basins in the Carolinas, and you'll also see a blue layer that is of flood plain. That's the 100-year flood plain. As you progress to the next tabs, you'll see layers that include concentrated animal feeding operations, so this is industrial agriculture, it's very high density, it's a lot of hogs out east, it's a lot of poultry, a lot of dairy. We are the number two producer for hogs, and with Hurricane Floyd in 1999, we saw a disaster with a lot of dead animals and a lot of waste released. We saw it happen again two years ago with Hurricane Matthew, and guess what, once again we're having a so-called 500-year flood event with yet another major hurricane so maybe this is not the best place to have a high density of so much animal waste.

A swine lagoon, photographed just days after the Hurricane. (Photo: Forrest English, Pamlico Tar Riverkeeper)

BASCOMB: The big concern with these feedlots is the lagoons that hold the animal waste, they can actually fill with rainwater and rivers rise up to fill in the lagoons and then spill out into the surrounding river. Can you talked to me a bit about the health concerns with that, with all this animal waste being spilled into the environment?

PERKINS: I know it might seem like this is natural animal waste, how bad could it be, but it is so potent you can get knocked off your feet just from the fumes from these facilities. You can have trouble breathing, and there are people, disproportionately people of color, who have to live with this every single day. They even found hog DNA on the inside walls of homes.

BASCOMB: Oh, God.

PERKINS: So, when the waste gets sprayed out on fields, it's not all going to the crops, it's going into the air and it's even going into people's homes, their bodies. There's, of course, a lot of a bacteria in this waste, so you do not want to get it in a cut, you don't want to have any contact with that, it can make you incredibly sick. And it's a problem that has just really stalled and not gone anywhere for two decades, and so I really hope that seeing the problems with this hurricane will remind people that we have to do something about this issue.

BASCOMB: And, Sam, what kind of legislative action has been taken to reduce the risk of flooding in these CAFO lagoons?

PERKINS: There has not been a whole lot of good legislative action in trying to deal with this very potent waste problem. In fact, we've seen kind of the opposite. The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality is the entity that really needs to be the one policing and forcing the protections that we have on the books, and instead the state has drastically cut funding and resources for them to be able to go out and check for instance, if you have a hog lagoon spraying waste when a flood watch has been issued, which is not supposed to happen, we go out, we fly over and we try to document this, but we have an enforcement agency that is grossly understaffed, does not have the resources to hold accountable these polluters.

Coal ash spilling from the site of the now-defunct Cape Fear Power Plant. (Photo: Emily Sutton, Haw Riverkeeper)

There was a moratorium passed on hog CAFOs 21 years ago because North Carolina realized this is out of control, we need to do something to at least stop it from growing and becoming too much worse. But unfortunately nothing really has happened since then, and the problems and the spraying and the waste locations have persisted, and that's across the governors of multiple political parties who could have done something. At the same time, poultry was not part of that legislation. So, the poultry industry came in North Carolina, they are exempt from public records, so they have exploded onto the scene.

BASCOMB: Well, you also have another layer on your map dedicated to coal ash facilities. Can you explain what is coal ash and where are the coal ash sites located?

PERKINS: North Carolina is the capital of coal ash. Coal ash is what is left over after you have coal that is burned to generate electricity. The ash that's left over is very concentrated in heavy metals. A lot of these occur naturally. Arsenic occurs naturally, but they get very concentrated in coal ash, and what power plants do is they mix that ash with water and they pipe it to a pond, and they dump it. These sites are unlined and surrounded by nothing but earth. This isn't like a concrete dam. These are not all that elaborate. I like to say they're like a pile of mashed potatoes holding back toxic gravy. That's sort of the comparison that you would use for the land, and we have 14 of these sites in North Carolina. The highest in the state is about 130 feet, and the ones in eastern North Carolina are very susceptible to failure, whether it's heavy rain, flood water. The Sutton site near Wilmington, North Carolina where Hurricane Florence made landfall as a category one, but still that site had a significant breach of coal ash, and the last thing you want is a potent source of heavy metals getting into your drinking water source.

A screenshot of Sam Perkins’s interactive map. This display documents the Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) in North and South Carolina. Many of these sites also house toxic chemicals at risk of being released into the environment during a storm. (Photo: WaterKeeper Alliance)

BASCOMB: So, what are these states doing to adjust the flooding risk for these industries or to make regulations to mitigate the risk?

PERKINS: North Carolina took a stab at trying to regulate coal ash after the 2014 Dan River disaster. It was a major blow out of coal ash, one of the largest ever recorded, but there hasn't been great enforcement. And now we're seeing some of the federal baselines, the minimal regulations that started to get set at the end of 2015 being attacked by the current administration. In South Carolina at least, utilities in South Carolina have realized this is not a great idea, and it did take water keepers and the Southern Environmental Law Center entering in litigation, but they said it's not worth the risk. We're going to clean up these sites, move away from water, recycling it in the concrete - which actually reduces the carbon footprint of concrete and improves the quality of concrete - and we're going to get this off of our portfolio as a risk.

BASCOMB: North Carolina somewhat infamously made it illegal to consider climate change when creating new laws or management plans for these types of issues, but I mean this is one of the most vulnerable states in the country when it comes to hurricanes and flooding and and the impacts on the economy and so much industry there. Do you think this experience of Florence might shift the thinking at all?

Sam Perkins of the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation. (Photo: Courtesy of the Waterkeeper Alliance)

PERKINS: It's difficult to say exactly, but it's embarrassing because we have great research institutions especially around marine science studying things like sea level rise, and we have great coastline, we have incredible beaches, we have the outer banks. Those are really valuable economically, so it is absolutely bizarre. You would think this would be a bipartisan common sense thing to say we need to do everything we can to preserve a very beautiful valuable natural asset and instead we're getting battered frequently by 500-year flood events.

BASCOMB: Sam Perkins is the RiverKeeper for the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me, Sam.

PERKINS: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Explore Sam Perkins’ Map Here

- Sam Perkins Profile

- More on the Catawba Riverkeeper Foundation

- New York Times | “Lagoons of Pig Waste Are Overflowing After Florence. Yes, That’s as Nasty as It Sounds.”

Science Note: Hurricanes, Lizards and Leafblowers

A female anolis scriptus lizard. (Photo: Rian Castillo, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Later in the show, the me too movement in climate change research but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[MUSIC: SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: A recent study published in the journal Nature, demonstrated that hurricanes might act as a force in natural selection for certain lizards. Scientists were already studying a species of anole, Anolis scriptus, a small lizard native to the Turks and Caicos, when Hurricane Irma hit their study area in 2017. The scientists returned to their research site after the storm, and observed that the surviving lizards had longer forelimbs, shorter hindlimbs and bigger toe pads on average, than the overall population of lizards present before the hurricane.

The researchers speculated that perhaps these body characteristics might have helped the remaining lizards survive the hurricane, meaning hurricanes could be a factor in natural selection, possibly affecting the evolutionary trajectory of the lizards. But the scientists also wanted to know how the lizards survived the hurricane to begin with. Did they hide on the ground, or in crevices in trees, or did they ride the storm out by clinging to branches and tree trunks?

A male Anolis scriptus lizard hangs on. (Photo: Rian Castillo, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

To find out they took lizards back to the lab, where they perched them on small wooden poles, then simulated hurricane force winds with a leaf blower, gradually ratcheting up the velocity. The researchers found that the lizards stayed on the perch, as opposed to fleeing, and moved to the lee of the perch – the side away from where the wind was blowing. As wind speeds increased, the lizards lost hold with their hindlimbs first, and hung on by their forelimbs until the wind was strong enough to blow them off their perches, unharmed, into a safety net.

If the lizards chose to hide from the wind there would be no reason to think longer or shorter limbs would have anything to do with their survival. But because the lizards chose to ride out the storm on their perch, longer forelimbs could be advantageous.

Scientists caution that there may be other explanations for the body characteristics of the surviving lizards, but hurricane-induced natural selection, or in this case a leaf blower, seems like the best explanation. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

The paper in Nature: “Hurricane-induced selection on the morphology of an island lizard”

BASCOMB: Just ahead – Catastrophe and community – Surviving Puerto Rico’s Hurricane Maria and the isolation that followed. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Isaac Hayes, “Something” on Let It Be – Black America Sings Lennon, McCartney and Harrison, by Lennon & McCartney/arr.Dale Warren and Isaac Hayes, Ace Records]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Isaac Hayes, “Something” on Let It Be – Black America Sings Lennon, McCartney and Harrison, by Lennon & McCartney/arr.Dale Warren and Isaac Hayes, Ace Records]

“Pa’lante”: Puerto Rican Resilience After Maria

Gloria Vasquez points towards the broken and battered trees behind her house. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

We continue our series this week on deadly Hurricane Maria. It’s the one- year anniversary of when Maria slammed ashore Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017.

Some 3,000 people died, but most of those deaths were not from wind and rain but the isolation that followed the storm. The slow aid response after the hurricane left vulnerable people stranded for weeks and months. Many died from treatable infections, contaminated water, or electrocution from downed powerlines. Nine months after Maria I traveled to Puerto Rico and found people that are now looking to each other, not the government, to create more resilient communities and prepare for the next storm.

[DRIVING SOUNDS GPS DIRECTIONS ‘IN HALF A MILE…’]

BASCOMB: To get to Humacao, Puerto Rico you can take highway 53, past McDonalds, grocery stores, and car dealerships. Except for the palm trees, it feels like you could be anywhere in the US. But turn up the narrow, twisty mountain road toward Humacao and it’s a different story. Electrical poles stick out of the ground at awkward angles. Electrical wires hang casually over the road, swaying in a light breeze.

NIEVES: There’s a lot of posts that look like they’re about to fall on people. Trees near highways that look like they are about to fall on cars. And that actually happened.

BASCOMB: Christine Nieves, she’s director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, based in a community center at the very top of the mountain in Humacao. Christina says downed power lines and unstable trees are now common here.

Christine Nieves is director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, founded after Hurricane Maria to help her community recover from the storm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: There was a tragedy not too long ago of a young man dying from having a tree collapse on top of him. So you’re still seeing that.

BASCOMB: Christine is petit with wavy black hair and a bright smile. She wears a flowy pink top and long earrings. She left Puerto Rico to go to college at Penn State and then got her master’s degree at Oxford in England. She came back to Puerto Rico 6 months before Maria hit the island and settled here in Humacao, where the hurricane actually made landfall.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

Christine leads the way across a large parking lot to the edge of the mountain and points to a wide green valley below us.

NIEVES: So this is where the eye of the hurricane enters.

BASCOMB: Through this valley?

NIEVES: Yes. It actually made landfall first in this community and all of these mountains.

BASCOMB: Just to describe this area where we are. So right there is the ocean, so that’s obviously where the hurricane came in and just traveled up this little valley in between us here, between the mountain that we’re standing on and that mountain over there and hit these homes right in front of us.

Hurricane Maria travelled up this wide green valley to the interior of Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: Mmhm, absolutely.

BASCOMB: Were you here during the hurricane?

NIEVES: I was, yeah. My house is actually not too far from here.

BASCOMB: So what did it feel like?

NIEVES: It was chaotic. We prepared so well because we had basically a two-week heads-up. We were prepared from Irma already. We had storm shutters were up. We got water you know, a few days before the hurricane and we filled our cistern. But the actual hurricane, because we were so close we started feeling it on the 19th. One in the morning, we wake up - we start feeling, and hearing, the sounds, and it’s just loud and you can barely hear each other. And that’s when we started noticing that the water was coming in, through all the windows.

These homes in Humacao were some of the very first in Puerto Rico to feel the impacts of the Hurricane. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: into your house?

NIEVES: yeah, through all the windows. Through the storm shutters, it didn’t matter. It was just coming through. And at first we were trying to figure out if we could dry the water and like address that. and then we also started noticing, we have all of our doors, glass sliding doors, and we noticed that the glass was bending inward, so to try to keep it from being pushed into the house, we took all of our furniture and backed it up to the wall, from the door to the wall, like in a chain. It was like, you know, the table, and the chair, and the bookshelf - and everything supported each other all the way to the nearest column.

But that didn’t help. And it was around 4 in the morning that the, skylights exploded in, and then the windows exploded in as well. So there was glass flying. So at that point we actually got into the safest spot, which was a bathroom under the staircase. Dog, cat, three adults, in this tiny bathroom, and just waited. And then we started seeing the water coming in from under the door. It’s just like coming in, and coming in, so we’re like, what do we do? So we just put everything we had and basically everything that got wet we had to toss away.

And it was just, the hurricane came in. So… it was not just water, it was leaves. And then the painting from inside the walls was stripped… scraped off from the pressure. It was like a pressure washer had come into the house and just scraped… not only outside, but inside.

BASCOMB: The paint came right off your walls?

NIEVES: Mm hm.

BASCOMB: That sounds really scary.

NIEVES: Oh yeah. I mean, it was… Luis is a musician, so he was playing - my partner - he was playing the guitar. His cousin is also, you know, his entire family plays some sort of instrument, so he was playing the drums, or the percussion. So we were dealing with it by singing. And we spent the entire hurricane like that. And then once we actually got into the bathroom there was not a lot of space, so we kind of took a nap, sometime in the middle of the night, because you’re so exhausted, and there’s nothing you can do, you know, everything’s getting destroyed. And when we came out at 7 in the morning, we noticed that the, our 2,000 gallon cistern - something had come off, so the entire cistern was getting, was emptying out. And that was just at the moment when the wind was changing directions. So we never felt the calm of the storm, we were kind of… it was basically the wall of the eye, we never got the actual eye.

A sign advertises that the Mutual Aid Project accepts $5 “solidarity donations” for lunch Monday through Friday. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

So this was like, that wall of the eye just passed right through us. And we got, because of our altitude, we also got the strongest winds, and some of the storm shutters were actually pulled off of the wall. It was like, it was something so massive that you can’t quite understand it and comprehend it, when you see that something that’s designed to withstand storms didn’t, that’s when you realize, ok, we’re dealing with something that’s beyond the scales that we’re used to.

BASCOMB: So this forest in front of us, I mean, you can see that it used to be a forest, and it still is to some degree, but there are no leaves really on the side of the trees and all of the tops are cut off at the same length, at the same height.

NIEVES: Yeah, so, all of these trees that you see here, they were massive. You couldn’t see beyond them. It was so thick, you couldn’t see the houses even. It looks much better eight months later, because nature is so wonderful and it can bounce back so much faster than human beings can in many ways. But that was actually one of the first things I noticed, that even before FEMA arrived to the island, to Mariana, we were seeing the trees bouncing back. So the trees were faster in their response, than FEMA even.

BASCOMB: It looks like just a big chainsaw went through and just cut the tops off everything and stripped the sides off the trees.

NIEVES: Mm hm, mm hm, yeah. It was like a bomb exploded. And it was also… if you had come here the days after, it looked just like sticks, like matchsticks, just like sticking up, everything looked grey, and it was actually one of the hardest things, because people who live here, obviously, love nature, and it’s one of the reasons I moved back, and it was very hard to see the amount of destruction. It looks like something went through, yeah, and cut them.

BASCOMB: When you came out here the day or two after the hurricane, how did it make you feel to see it look so different, to see the trees just denuded?

NIEVES: when we walked out of the bathroom and went to one of the windows in the house, we were on the bottom part of the house… oh my god, I - Luis, actually, my partner, he started crying, because those were the trees that he grew up with. And it was just a complete feeling of… it was like all the movies that you’ve seen of Armageddon, of destruction, of the end of days, it was like - this is done. And the fact that the communication collapsed meant that also we couldn’t hear the government, but we couldn’t hear each other. All we had was the people next to us.

Eight months after the storm Puerto Ricans were still being injured and killed by falling trees and electrical poles. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In my 2.5 weeks reporting in Puerto Rico I heard this same sentiment over and over again. Communities were isolate, FEMA and the government were slow to respond, so people turned to their neighbors for help. In many cases the dense forest before the hurricane had blocked their view of each other. People might not even know there was a house across the street or down the way a bit but after Maria turned the lush forest into match sticks neighbors could see each other for the first time and came to rely on one another for help.

NIEVES: the people in this area that are starting to understand that the government is not going to respond and save them, it’s actually going to be their neighbors, having, you know, the machetes ready. Knowing how to disinfect a wound. That’s one of the things that they saw the most, was wounds that could have been disinfected actually ended up in amputations. So they had to cut so many feet off because people were wearing flip-flops in standing water that had infections and they just couldn’t, they didn’t have something like iodine or something that could be easily over-the-counter, anyone can have, disinfecting the wound at the right time. So, it’s that kind of education and preparedness and it’s also community organizing to prepare for the next hurricane.

BASCOMB: Most of the residents of Humacao are older, retirees, who live alone and have been without electricity since the hurricane. Christine takes me to meet one of them.

NIEVES: So, let’s go find Gloria.

[CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I follow Christine down the mountain to meet Gloria Vasquez at her house a few miles away. A downed electrical wire grazes the top of a car parked in front of her house. She’s standing on her porch watering a potted pepper plant.

Gloria Vasquez standing in her living room. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Buenas!

VASQUEZ: Hello, buenas!

BASCOMB: Como estas?

VASQUEZ: Bien, bien.

VASQUEZ: Let me show her something I am planting.

BASCOMB: Of course.

BASCOMB: Gloria is 70 years old, she wears an oversized red t-shirt and her hair slicked back in a small pony tail. Her house sits on the side of the mountain overlooking the valley. She can see clear to the ocean some 40 miles away. Before the hurricane Gloria says she could only see the dense forest in her yard and an avocado tree taller than her house.

VASQUEZ: the tree, it was so big, tall. It feel me very very bad. And I cry like crazy. Because I don’t think that Puerto Rico is going to be like that, you know.

BASCOMB: You didn’t think it could look like that.

VASQUEZ: No, no. No, I don’t think it’s going to be like that. And still I hurt. I feel, you know, about what happened to Puerto Rico.

BASCOMB: Gloria has accepted her lost trees and the broken landscape but she’s still struggling to deal with day to day life living alone without electricity.

GLORIA: It’s hard. Sometime I sit there and I cry because the light, I need the light, you know? I don’t have no fridge, to cool my stuff, because I got diabetes and I need to put my insulin in the fridge.

BASCOMB: So what do you do?

GLORIA: sometime I take it the lady’s in my neighborhood, Sandra, and then Sandra let me, give me a key to put them inside the refrigerator. She got a generator.

BASCOMB: How do you manage it at nighttime?

Each week a group of volunteers gathers to cook for the community. Feeding their neighbors is a type of therapy. The ladies get out of their lonely dark homes for the day and connect with friends. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: By 6:30 it’s starting getting darker so I lock the gate and I lock the door and I stay inside the house, ‘cause you don’t know, you know. There’s a lot of thief here

BASCOMB: A lot of theft.

VASQUEZ: Yeah. They ask me, oh are you there by yourself - no, I’m not by myself. I got a husband. My husband is the police and he is working.

BASCOMB: Gloria lived most of her life in the Bronx. She moved there as a teenager with her family and worked for 50 years, mostly as a hair dresser. She saved her money all those years to retire in her native Puerto Rico where she bought this 3 bedroom cement house.

VASQUEZ: You want to come inside the house?

BASCOMB: Yeah.

[SFX - shuffling into house]

VASQUEZ: This is the living room over here. This is my dining room, and the kitchen. You see, it’s dark. Let me get the flashlight.

BASCOMB: Gloria shows me around her dark house. She pauses at a crèche and a statue of the virgin Mary given to her by her mother.

GLORIA: She gave me this one and this one here. They always here with me. Those are the ones that take care of me.

BASCOMB: She points out framed pictures of her grandchildren and her three sons.

GLORIA: That’s my baby boy here when he graduate.

BASCOMB: How old is he now?

VASQUEZ: He’s going to be 40. And that’s me when I graduate from beauty school. Midway Beauty School in New York.

BASCOMB: In her tidy kitchen Gloria has a few vegetables on the counter, a gas stove, a refrigerator empty but for a bottle of maple syrup, and a small red cooler on the floor where she keeps perishables like milk.

VASQUEZ: But I don’t buy no meat, because meat is getting worse quick.

BASCOMB: It goes bad quickly.

VASQUEZ: yeah

BASCOMB: What do you eat then?

VASQUEZ: If I want to eat something, I go into the store right there, I buy whatever I want to eat, and then I bring it. Today I’m gonna eat verdura.

BASCOMB: vegetables

VASQUEZ: Yeah. This is my dinner for today.

BASCOMB: Eggplant and plantain

VASQUEZ: eggplant, banana, and potato. That’s my dinner and my lunch, is going to be today. And this, hamonia.

BASCOMB: That’s like spam.

Maria cooks up chunks of pork for lunch at the community center in Humacao. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: Yeah, spam. And then I cook it and eat half, and I leave the other half for later. That’s the life here. Hard, hard. But what I gonna do?

BASCOMB: That’s the life for most of the residents in Humacao. The majority of people here are elderly, living alone, and without power. That isolation can be depressing and deadly. But since Maria hit locals are looking to each other for solace and sustenance.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

The next day I drove the twisty road back to the mountain top community center in Humacao. Half a dozen older women have gathered today to cook for their neighbors, as they do each week, Monday through Friday.

There’s a sign out front that indicates when they’ll be cooking and says ‘aceptamos donativos solidarios’ we accept solidarity donations. For five dollars any one can buy a home made lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Maybe some fruit if one of the ladies has extra papaya or pineapple coming up at home. Today a woman, ironically named Maria, is cooking up chunks of pork.

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

MARIA: I like to make the meat soft and nice and tender. Would you like a bite?

BASCOMB: it’s very good.

MARIA: it is, it is. rice and beans… oh gosh we’re eating good here.

BASCOMB: Maria says coming here to feed the community is a type of therapy for her. She gets out of her lonely dark house for the day and cooks with her friends. They chat about family and argue like sisters. Life feels normal again.

This theme of working together and resilience is everywhere in post- Maria Puerto Rico.

Lunch is served! For $5, anyone can buy a lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Beyond food, community members can connect with one another and feel less alone. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

About 9 months after the storm a local musician named Hurray for the Riff Raff produced a song in part about recovery on the island. The music video shows scenes of hurricane ravaged communities and tells the story of a young family trying to work through it.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

Pa’lante is truncated from the Spanish phrase para adelante, which literally means move forward but Humacao community organizer, Christine Nieves says it means much more than that now.

NIEVES: So, ‘pa’lante’ means we’re going to keep moving forward, we’re going to keep rising, and we’re going to keep fighting. it’s about connecting with the root. we’ll look back at this moment in history and I think it’ll have a huge fork on the road in what it does to the Puerto Rican psyche. The conclusion at the end of this disaster that we’re still living in is that it’s us, we were the ones that could respond. We were the ones that were capable of saving lives, and it was community members that were capable of doing it. So, pa’lante. We keep building, we keep building.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

BASCOMB: If there’s any silver lining to the devastation that Maria brought here it might be this: a renewed sense of community, Puerto Rican pride, and resiliency that people hope will keep them moving forward to rebuild and meet the next challenge together.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

Related links:

- Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo

- Hurray for the Riff Raff

BASCOMB: Coming up – Using a smart phone app to forage for food in the city. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Samite, “Resilience” on Resilience, Samite Music]

Beyond The Headlines

Hurricane Florence is one of many natural disasters that have affected the southeast barrier islands. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Let’s take a look now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org. Hey Peter!

DYKSTRA: Hi Bobby. Let’s look at a piece from the website Citylab. They looked at an aspect from Hurricane Florence that a lot of people haven’t examined or even considered. We see plenty about the storm surge, the beach damage, in inland flooding, the power failures, the fallen trees. But there are an estimated 200,000 Gullah and Geechee people who live in the Southeast, mostly on barrier islands along the coast, and they don’t have all the legal paperwork to show that they own the land when they, out on the barrier islands, become some of the first victims of a hurricane.

BASCOMB: Why don’t they have the legal paperwork?

DYKSTRA: It’s happened over years – the Gullah and Geechees are descendants of slaves, the land has been handed down to them over generations, and the paperwork system that’s common in most places just never happened along the coast for the Gullah and Geechee people. And it makes for a real hard time when they go to apply for aid or loans from FEMA and other agencies in the wake of hurricane damage.

BASCOMB: Right, yeah, I can imagine that must be a really difficult situation for them.

DYKSTRA: And on the other side, even though those barrier islands are eventually going to be damaged beyond repair, and maybe even disappear from sea level rise and increased storms, there are still developers looking for that valuable coastal land, trying to buy the Gullah and Geechee people out, turning traditional land into golf courses and resorts.

Bisphenol-A found in many plastic containers and water bottles is known to be harmful, but the substitute Bisphenol-S could be just as bad. (Photo: MMarsolais, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, golf courses and resorts that are going to be flooding in the coming decades. What else do you have for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, we go into supermarkets and you see lots of proclamations, marking pitches on packages that something is “gluten-free” or “98% fat free”. One of the increasing ones, in recent years, has been on plastic bottles and containers, saying that they’re “BPA-free”. Bisphenol-A, a substance that’s been found to mimic hormones, specifically estrogen, and play havoc with the human reproductive system.

BASCOMB: So, what’s going on with that now?

DYKSTRA: Well, there’s a researcher who’s been a pioneer in BPA research named Pat Hunt at Washington State University, and she and her team have found that BPA substitutes that are being marketed – there’s another one called bisphenol-S – may be just as bad, just as harmful, just as risky, as bisphenol-A, BPA.

BASCOMB: Man, well, back to the drawing board for that, then, I guess.

DYKSTRA: Right.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: You know, it’s been over a century since hydrodams became a source of hydroelectric power in rivers all over the country, but the older ones have become obsolete as a source of power. One thing they’re still very effective at is blocking the progress of migratory fish.

BASCOMB: Right, fish like salmon need to migrate up rivers to reproduce.

DYKSTRA: Right, anadromous fish, the ones that live much of their lives in the ocean but come into rivers to reproduce. Not only salmon, but steelhead, shad, and sturgeon. And on September 23rd of 2011, on the Elwha river, in Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula, the process started to remove an obsolete hydrodam. This is one of the biggest such projects in the country.

BASCOMB: Right, we did a few stories about that back when the dam was being taken down. Do we know anything about how the river’s doing today?

DYKSTRA: The river’s doing pretty well. It’s hard to restore a river to its absolute pristine natural state, but the Elwha is recovering nicely, those anadromous fish are coming back, as they are in other places like the Penobscot River in Maine, where a mid-19th century dam was removed several years ago.

After the removal of the Elwha Dam, Washington’s Elwha River has begun a return to its former glory. (Photo: John McMillan, NOAA, Wikimedia Commons - Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Right, we did a story about that as well, actually. Well, thanks for those updates, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: You can find more on these stories on our website, L-O-E dot O-R-G.

Related links:

- CityLab | “After Florence, the Gullah Could Face New Threats”

- Living on Earth | “Undamming the Elwha”

- Living on Earth | “Helping Fish Return to the Elwha River”

- Seattle Times | “WSSU Researchers Say BPA Alternatives Pose Health Risks”

[MUSIC: Jeff Little, “Minor Swing” on Piano Man from the Blue Ridge, composed by Reinhardt/Grapelli, self-published.]

Women Climate Scientists Threatened and Harassed

“Defending Science Is Defending Women,” reads a sign carried in the San Francisco, California Women’s March on January 21st, 2017. (Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: The Me Too movement of women exposing the prevalence sexual harassment and assault, has made it’s way across the spectrum of American life from entertainment to media, and now famously again to US Supreme Court choices.

Sexual harassment also affects women working the STEM fields, putting science, technology, engineering and math degrees to work. But women only hold about a quarter of those jobs. And in a male-dominated workplace sexual harassment persists.

A recent study found that 58 percent of female academic faculty and staff working in STEM fields have experienced sexual harassment. And for women who work as climate scientists, harassment can be especially brutal, intensified by the polarized politics of climate change. Male climate scientists receive attacks and threats as well but for female climate scientists those attacks often have a sexist, even violent tone. To learn more we turn now to Lauren Kurtz. She’s the Executive Director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. Welcome to Living on Earth, Lauren!

A protestor at the Boston Women’s March in 2017. A number of people who participated in this march, and corresponding marches across the country, were there to call out President Trump’s disparaging comments about science and women. (Photo: Jarred Barber)

KURTZ: Thanks so much.

BASCOMB: What specifically are some of the kinds of attacks that women in climate science face?

KURTZ: I think there's really two sorts of issues. One is the sorts of issues that all climate scientists face. These days it can be issues of government censorship, hostile messages on Twitter, e-mail, or voicemail. Things like misuse of state open records laws. And with women scientists, there can sometimes be this extra layer of hostility or aggression or discounting of the issues that has a flavor of sexism sometimes.

The second kind of attack they can face is just over outright sexism, rape, threats, sexual harassment, those sorts of things. We deal with less of the second part. We're really founded to deal with overall the sorts of attacks that scientists face, but we do sometimes have women scientists come to us and say my advisor groped me in the field, in which case, we usually try to refer them to someone who deals a little bit more concretely with those sorts of issues, or we get scientists who come to us and say I'm dealing with situation where I work for the government and my supervisor is no longer letting me talk to the press. And at times there's been a perception that they're not being taken as seriously or they're experiencing actual hurdles because of some sort of ingrained sexism. And again, these things can happen to male scientists but there's not the misogynistic overtones.

BASCOMB: Right. Male scientists aren't getting rape threats.

KURTZ: I have never heard of that one, and this isn't to say it hasn't happened, but that has not come to our doorstep anyway.

BASCOMB: I've read that studies show men are actually more skeptical of climate science than women. Why do you suppose that is, and how does that play into how female scientists are treated?

KURTZ: Yes, an interesting one. I will say that my experience is that people who reject climate science a non-zero amount of time often overlap with people who are also raging misogynists. In some ways it seems like they want to come back to a 1950s perception of the world where women knew their place, climate change was not an issue, America was an economic powerhouse, that sort of era. I don't know why that is exactly, but that does seem to be how things play out sometimes.

BASCOMB: Well, what recourse do climate scientists have when they receive these kinds of attacks? What can you actually do for them?

Michael Mann, Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University, became the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund’s first client when a climate denial group sought to obtain 38,000 of his emails. (Photo: Penn State University)

KURTZ: We have helped the scientists serve a restraining order someone who is leaving death threats on voicemail. We'll do things like will explore internal grievance channels. We'll also look at things like external whistleblowing complaints. When it comes to things like harassing messages on Twitter, there's opportunities perhaps to contact Twitter and let them know that they have a user who sending threatening messages. There's opportunity sometimes if there's ongoing litigation to help the scientists intervene so that they can have their voice heard in a larger issue. So, it really depends.

BASCOMB: To what extent do you think threats and attacks on climate scientists come from random individuals or are they sometimes orchestrated by larger forces, organized groups?

KURTZ: Yeah, so that's a really good question. It's actually both. There are definitely some lone wolf types who, for whatever reason or another, enjoy doing these sorts of things sending nasty e-mails or Twitter messages. The more insidious stuff though in a way I would categorize as organized.

BASCOMB: Really.

KURTZ: Yes. So, we were formed actually to help scientists who get embroiled in bogus litigation, and that's a sort of thing that is unfortunately pretty well funded. There are several groups out there that as part of their mission to reduce the regulations surrounding the oil and gas and coal industries, they try to discredit researchers. Through that discrediting they can really get pretty hostile and invasive and harassing, and that sort of thing we know now is actually funded by the coal industry and the oil and gas industry.

Lauren Kurtz is the Executive Director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. (Photo: Climate Science Legal Defense Fund)

BASCOMB: Can you give us some specific examples if you're willing to name names of the institutions that are funding this sort of harassment of climate scientists?

KURTZ: Yeah, so there are definitely a number of groups out there and they have been decently well covered in the news, in part, because a number of the people who have worked at these groups are now or have been at one point members of the Trump administration. There's a group called the Energy Environment Legal Institute. They use the legal system to target scientists. They'll try and do things like, in one situation, obtain 13 years of e-mails with a pretty blatant attempt to try and find something in an e-mail that they can use to take out of context and thereby seemingly try to discredit climate science as a whole. There's another related group called the Free Market Environmental Law Clinic they do basically the same things and work in conjunction with any legal.

BASCOMB: And of course climate scientist Michael Mann knows about that all too well. I mean that's exactly what happened to him right?

KURTZ: Yeah, so Michael Mann is a climate scientist who at one point was at the University of Virginia. He is now at Penn State. He was actually the first person that we helped. There was a group out there, in fact, the predecessor to the Energy Environment Legal Group. They tried to use state laws to obtain virtually every e-mail that he'd ever sent or received while he was a professor at the University of Virginia. It was something like 38,000 messages. I mean, surely if you hand a hostile party, 38,000 emails, some of which were just sent to you that you didn't write yourself, I'm sure there was a phrase or two in there that could be taken out of context. So, we were founded to help fight that. It was successful thankfully.

BASCOMB: Lauren Kurtz is the executive director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund. Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me.

KURTZ: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Climate Science Legal Defense Fund

- E&E News | “‘Ugly fake scientist.’ Women say sexist attacks on the rise”

[MUSIC: Jeff Little, “E.M.D.” on Piano Man from the Blue Ridge]

An App For Urban Foraging

David Craft picks black cherries from a tree in Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

BASCOMB: It’s the end of summer, a time when many city-dwellers visit local farms to go apple or peach picking. But if you know what you’re looking for harvestable food is actually all around us, even in cities. Urban foraging might sound fun but how do you get started? Well, like many things, there’s an app for that. Living on Earth’s Savannah Christiansen has our story.

[CITY SOUNDS]

CHRISTIANSEN: Memorial Drive in Cambridge is a busy thoroughfare full of traffic. It’s right across the Charles River from Boston. An unlikely place to look for edible plants but David Craft says that Magazine Beach Park, which sits between the busy road and the river, is one of the best places to forage.

CRAFT: Well right around here, there's burdock, and there’s milkweed and there’s oak trees for acorns. There’s Evening Primrose, Japanese knotweed.

CHRISTIANSEN: The thick clumps of weeds and grasses along the river bank are full of edibles.

CRAFT: Sometimes I find like lambs’ quarters and ladies thumb. I see some inky cap mushrooms right there by the base of that tree.

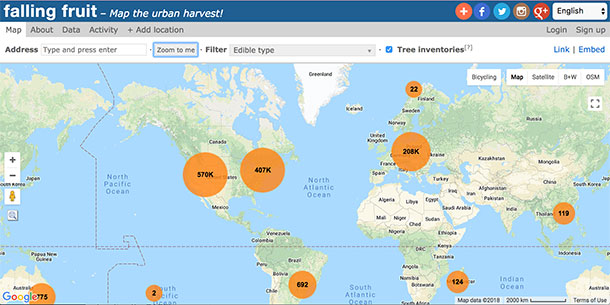

CHRISTIANSEN: David is an Assistant Professor of Radiation Oncology at Harvard Medical School. He’s also a local foraging expert. But if you don’t happen to have a foraging guru handy, there’s the Falling Fruit app, an online map that uses imported datasets to guide foragers to the locations of public fruit trees, edible plants, and mushrooms.

David and I pull open the map on our phones.

CRAFT: If I zoom into that guy...pokeweed.

CHRISTIANSEN: Some pokeweed? Mulberry?

CRAFT: Yep. Evening primrose, serviceberry

CHRISTIANSEN: Orange dots on the map indicate the location of an edible. Sometimes it simply names the species. Other times, a user writes a description of the plant and a tip for when to harvest. For instance, mulberries are only good in June, and Linden leaves and Evening Primrose roots can be harvested in early spring. I notice a more familiar name on the other side of the park: black cherry. The user warns they’re not as good as store-bought cherries, but David and I make our way over to check them out anyway.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

CHRISTIANSEN: We don’t get far before David stops and pulls a slender, white tuber out of the ground.

The home page of the Falling Fruit map. (Photo: Fallingfruit.org)

CRAFT: This is the wild carrot. It’s also known as Queen Anne's lace. You wouldn't eat it right now because it's too woody. Usually when a plant is flowering is not when you want to forage it. You want to eat the wild carrot when it looks like this, that's a new, young wild carrot we could actually eat that one, that one would be soft enough. And then you could…

The carrots you buy across the street there at Trader Joe's are a lot better than this. However, you can at least taste the distant memory of a carrot. You know it’s stringier. It's got a bitter aftertaste. But a long time ago people said, “hey it’s pretty good, let's bring these into our garden and let's select the ones that are bigger, and you know my gosh there's more one with an orange root!”

CHRISTIANSEN: David samples many of the things we walk by, crushing and smelling leaves in his fingers to help identify them. He stops at a shrub growing in the cracks of the sidewalk.

CRAFT: It’s called pineapple weed. It’s closely related to Chamomile and you can make a good tea out of this, and if you squeeze that and smell that, it's like a pineapple-y scent?

CHRISTIANSEN: Yeah, its fruity.

DC: Yeah fruity. It likes the beaten down, sandy soil next to bike paths. That’s actually its preferred habitat I find. Really compact, sandy, busted soil that nothing else likes to... it thrives there.

CHRISTIANSEN: We continue following the little orange dot on our phones towards the cherry tree.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

CRAFT: Here we're coming up to a black cherry tree.

CHRISTIANSEN: Wow right on the edge of the bridge here!

DC: Yea see the cherries up there? They’re small...

CHRISTIANSEN: Oh, I didn’t realize it was such a large tree.

CRAFT: Yeah.

CHRISTIANSEN: All right so any of the dark ones are good?

CRAFT: Any of the dark ones are good to go. They have a pit. They're definitely not as good as a store-bought cherry.

David holds up a young, wild carrot, also known as Queen Anne’s lace. (Photo: Savannah Christiansen)

CHRISTIANSEN: They're slightly more bitter than regular cherries, but they’re good.

CHRISTIANSEN: Unlike store bought produce, wild foods don’t all taste the same just because they’re the same species.

CRAFT: Now, you could find another cherry tree, perfectly ripe, somewhere across town right now and it would taste horrible.

CHRISTIANSEN: Why?

CRAFT: I'm not sure if it's a genetic thing, or if it's the soil that it's growing in. So it's like nature versus nurture, I don't really know. But this is a particularly good black cherry tree.

CHRISTIANSEN: Despite the wealth of foraging possibilities, David says he still feels like the practice hasn’t caught on with many people.

CRAFT: I still can count on one hand, almost, the number of times I've seen other people out here foraging. And it drives me nuts when I’m picking some strange fruit from a tree in the middle of Boston and people walk right by me and they don't even ask it's like are you kidding me? You’re not slightly curious as to what this crazy guy is doing?

CHRISTIANSEN: So, you would want people to ask?

CRAFT: Yeah sure a little curiosity. And talk to your neighbors! People around you, you know? And it’s a nice it's a nice way to spend time with people too, you know, you can say “hey let's go for a walk in the river and try to identify some plants.” But if you're so cautious you don't try anything you're never going to kind of experience the fun that comes with harvesting a meal, or at least a snack.

CHRISTIANSEN: Foraging for snacks might be an unlikely activity for most people but a growing number of cities including Boston, New York and Los Angeles actually offer foraging tours each year. And for anyone who wants to skip the farm and go apple picking in their neighborhood this fall, there’s the Falling Fruit app. For Living on Earth, I’m Savannah Christiansen in Boston, MA.

Related links:

- Falling Fruit: Map the Urban Harvest!

- David Craft’s Foraging Live Blog

- David Craft’s book, Urban Foraging

- Netta Davis’ YouTube videos on foraged foods

- Mother Nature Network “Urban Foraging is on the Upswing”

[MUSIC: New Black Eagle Jazz Band, “Peace In the Valley” on Higher Ground, self-published]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Sarah Rappaport, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. Steve Curwood is the Executive Producer of our show, and he’ll be back next week. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth