December 7, 2018

Air Date: December 7, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Meet Deb Haaland, Native American Congresswoman

View the page for this story

New Mexico’s 1st Congressional District is sending to Capitol Hill one of the first two Native American women to ever go to Congress, both elected as Democrats in 2018. Deb Haaland campaigned on climate change and other environmental issues, and cites a lifelong care for the environment inspired by her father. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood talks with Deb about her environmental priorities for the new Democratic-majority House of Representatives. (09:35)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to take a look at the environmental legacy of the late President George H. W. Bush, who strengthened the Clean Air Act, signed the UN Climate Treaty and once expressed a desire to be the “environmental president” of the United States. (03:20)

The Environmental Voting Gap

View the page for this story

Those US registered voters most likely to put the environment or climate as a top priority are young, African-American and Hispanic. But only about a fifth of these ‘super-environmentalist’ voters actually turned up at the ballot box to vote in the 2014 midterm elections, well below the national turnout rate. They came out in larger numbers in 2018 but still below national turnout rates. Environmental Voter Project Founder Nathaniel Stinnett joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what it might mean for environmental policies if politicians tap into this base of some 20 million ‘super-environmentalist’ registered voters. (11:20)

The Right To Repair

View the page for this story

The Right to Repair movement promotes resources people need to fix their stuff, from smartphones to dishwashers to agricultural equipment. The movement started as a response to the growing stream of e-waste but has expanded past that. Nathan Proctor is the Director of US PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign and he spoke with Host Steve Curwood. (06:00)

Is Shopping In A Store Greener Than Buying Online?

/ Jaime KaiserView the page for this story

Some like to buy gifts amid the festive atmosphere of a mall around Christmastime, while others would prefer to buy gifts online. And this decision can impact not only our budgets but the planet as well, but is there a right answer? Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser reports. (03:20)

Green Gifts For The Holiday Season

View the page for this story

Some holiday gifts can create needless consumption. But there are greener ways to show care to loved ones, from books that inspire stewardship, to sponsorships for animals in need. The Living on Earth team is here to share our “green gifts” in hopes of inspiring gifts that are ever-green. (05:30)

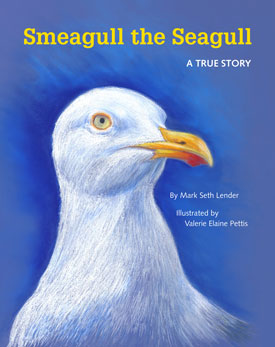

Smeagull The Seagull: A True Story

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Smeagull the Seagull comes to the house near the shore every day and knocks on the sliding glass door. He knocks when he’s hungry and the people who live there feed him. Those humans are Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender, and his wife and illustrator Valerie Elaine Pettis. Their new children’s book Smeagull the Seagull: A True Story teaches young children about the value of experiencing and protecting animals and nature. Mark reads his book aloud. (06:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Deb Haaland, Nathan Proctor, Nathaniel Stinnett

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Jaime Kaiser, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Deb Haaland is one of the first two Native American women to serve in Congress and she wants to represent those who often don’t have a voice.

HAALAND: You know when climate change hits, it’s the folks who can't afford to move, folks who can't afford to rebuild, it’s people who can't afford to endure the cost that climate change brings with it. So, we have to ensure that these folks actually do have a voice.

CURWOOD: Also, the ecology of holiday shopping in a store or online?

MAN: I’m staying with a friend right now and he had a huge shipment from Amazon yesterday, so I was just like, how much waste is there, boxes, and from ordering stuff online, like, I think it’s insane.

CURWOOD: Though kids do like to play in those big boxes. We have that and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Meet Deb Haaland, Native American Congresswoman

In 2018 New Mexican Congresswoman Deb Haaland bcame one of the first Native American women elected to Congress, along with fellow freshman Sharice Davids from Kansas. (Photo: Deb for Congress)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On November 6th, Deb Haaland from the Laguna Pueblo tribe in New Mexico became one of the first two Native American women to be elected to Congress. Sharice Davids of the Ho-Chunk tribe in Kansas is also an incoming freshman in the House of Representatives, and both women are Democrats. Congresswoman-elect Haaland previously chaired New Mexico’s Democratic party, and she joins us now. Welcome to the show, Deb!

HAALAND: Thank you so much. Really happy to be here.

CURWOOD: And happy belated birthday.

HAALAND: Oh, thank you. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Help me with some nomenclature. How do you describe yourself? Some people say Native American. Other people say indigenous. How do you identify your background?

HAALAND: I identify as a Native American woman, a Pueblo woman, if you will, from New Mexico, the daughter of veterans, a single mom, a grassroots organizer.

CURWOOD: How ancient is that society of Pueblo?

HAALAND: Well, you know, the Pueblo Indians, that's a Spanish word that essentially stuck when the Spanish came in the late 1500s. And the Pueblo Indians migrated to this area of New Mexico in the late 1200s, from Bears Ears, from Chaco Canyon, from Mesa Verde. So, the Pueblo Indians have been in the Rio Grande Valley and beyond, since about the late 1200s.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the platform that you campaigned on, in terms of the environmental issues. I think you were involved with renewable energy, and so forth.

HAALAND: Right. So, here in New Mexico, we have 310 days of sun per year. It seems to me that we are ripe to be a global leader in renewable energy. And, we should be. And I'm happy to note that up and down the ticket, we elected Democrats who believe strongly in renewable energy and fighting climate change. So, I feel like we'll be able to make some positive changes here in New Mexico.

CURWOOD: So, in the beginning of January, you get to raise your right hand and become a member of what is it, the 116th Congress?

HAALAND: That's correct, yes.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what you want to work with your colleagues there to get done in terms of environmental and conservation issues.

HAALAND: So, I was back in DC this past week for orientation week. And during that time, I participated in a press conference for the Green New Deal. And there are a number of legislators who are committed to that. Part of that is making sure that the Democrats come up with viable and, I mean, I want to say hardcore, renewable energy infrastructure plan, right? I think we have to be very strong on this issue. You know, there are still climate deniers out there and it's up to us to really push this issue to make sure that we're building relationships around an infrastructure plan that everybody can get behind it. You know, when we've seen all of these hurricanes, and droughts, and fires in California, we have a responsibility to these communities to be a leader in fighting climate change, moving toward renewable energy.

Cong. Deb Haaland(D-NM) is a member of the Laguna Pueblo Tribe in New Mexico. (Photo: Pueblo Laguna)

CURWOOD: The Trump administration is taking a number of steps to move ahead with fossil fuel, everything from shrinking the Bears Ears National Monument - so there could be resource extraction there - to opening up the Arctic National wildlife refuge for drilling for oil. What do you intend to do about these developments while you're in Washington?

HAALAND: We did win back the House this time around, so we can stop any bad legislation that's coming out of the Senate, for example. We can also hold hearings on issues, right? We can hold hearings on the environment, we can invite scientists, we can get all of these things on record. But I think we need to look at what's happening. We don't have to drill more. We don't have to increase the fossil fuel industry; we instead should put our resources toward renewable energy and find ways of making sure that we're coming into the 21st century.

CURWOOD: Congresswoman, talk to me about how indigenous rights are closely linked to environmental justice, in particular climate justice, from your perspective.

HAALAND: Right, of course. Well, I went to Standing Rock in September of 2016, to stand with the water protectors. I felt it was an important movement that I needed to be present at, just to make sure that I was lending my voice and adding my voice to that movement to protect a sacred lake and essentially water for this tribe. What it highlighted was that there are so many sacred sites and traditional homelands of Indian tribes that are not within our tribal boundaries. That doesn't mean that we shouldn't have a voice in how those lands are developed. That land was Indian land long before it wasn't. I just feel like we need to make sure that Indian tribes have a seat at the table, that they should have a voice in how this land is getting developed, in how things are moving forward. And so, I really feel strongly that environmental review should include a voice for tribes in any area. And if they are sacred, traditional sacred lands, that we should find a way to respect that as a country and as a government.

HAALAND: What's your perspective on the disenfranchisement that indigenous peoples endure and how they are often disproportionately affected by environmental issues?

CURWOOD: Right. Well, of course, that has a lot to do with voting as well, we saw that happen this time around. It wasn't just Native Americans, it was African Americans and Hispanic Americans. People, who are on the ground, whose voice needs to be heard above so many other peoples, and yet they found a way to ensure that they didn't have a way to vote. You know, if we take North Dakota for example, the legislator who penned the law that would disenfranchise Indian tribes in North Dakota was defeated by a Native American woman, Ruth Anna Buffalo. And I want to work hard on voting rights when I get to Congress because, when climate change hits, it's the folks who can't afford to move, folks who can afford to rebuild, it's people who can't afford to endure the cost that climate change brings with it. So, we have to ensure that these folks, the underrepresented people in our country, actually do have a voice and, and I really want to make sure that they do.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about being one of the first Native American women elected to the US Congress?

HAALAND: I mean, I'm humbled, of course. I'm honored, I'm humbled. I realize the weight that I will carry. This year in Congress, we've had more women of color elected to Congress than any time in our history. The first two Native American women after 240 plus years of not having representation, Native women finally have representation in our Congress.

CURWOOD: You're part of an incoming class that’s making history - more people of color, more women. What kind of a difference to think this is going to make in terms of America's attitude towards conservation and environmental stewardship?

HAALAND: Well, I think that it's going to make a huge difference in – it’s environmental stewardship, yes, there's so many of us, who you've seen in the news who want a green New Deal, who campaigned on that. And I think, you know, a lot of us will stand together to make sure that we're working on that. But also other voices. There's an incoming freshman, Lucy McBath, whose son was killed, who was murdered by gun violence. And she turned her grief into activism, the ultimate activism, right? She ran for a seat in Congress and won.

Deb Haaland (D-NM) is one of the growing group of elected representatives who have signed on to the Green New Deal, started by New York Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. (Photo: Deb for Congress)

So, a lot of these issues that legislators just wouldn't touch or their voices, the ones who wanted it got drowned out. But I think that all these voices together, they're going to help us live in a new world and fight for the issues in an effective way to make sure that we are getting things done. You know, I did a TEDx ABQ talk one time. The title of it was "Who Speaks For You", but essentially, it was about what if all of our elected officials looked like the communities they serve, right? We would live in a different world. And so, I think more of that is happening as time goes on and it absolutely happened to a lot of districts in this election.

CURWOOD: So, what made you so passionate about nature and the environment?

HAALAND: My dad grew up on a farm and was extremely close to the environment. He wouldn't lecture us about nature, he would take us out and we walked for hours just walking along the beach and not saying a word. Nature was something that was very dear to him, that he felt compelled to share with us. So, me and my siblings, we care deeply about the environment, all of us. And so in this new position that I have, I'll have more of an opportunity to protect it.

CURWOOD: Deb Haaland is New Mexico's Congresswoman-elect and one of two first Indigenous women in the United States Congress. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HAALAND: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Deb Haaland’s campaign platform

- Deb Haaland’s environmental priorities

- More information on the Pueblo Laguna tribe

- Updates on the protests at Standing Rock

- The Select Committee for a Green New Deal Draft Text

[MUSIC: Alan Miceli, “Mocha Java” on One Meatball, Appleseed Recordings]

Beyond The Headlines

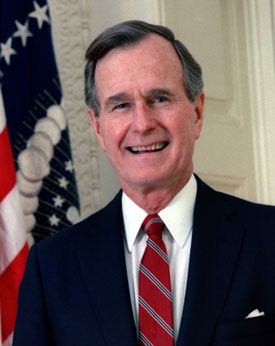

Former President George H. W. Bush passed away on November 30, 2018. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Andrea Hanks, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the man who looks beyond the headlines for us here at Living on Earth. And he's on the line now from Atlanta. Peters an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We’ll talk a little bit about George Herbert Walker Bush, George Bush Senior. We’ve heard so much about him and his passing. There's a lot more to focus on for George Bush and the environment. He was a New England Yankee turned into a Texas oilman. And if you measure him by the standard of a Texas oil man, or even by the standard of a 2018 Republican, he was also somewhere between a good, or at least a benign, force on the environment.

CURWOOD: For example?

DYKSTRA: Well he started in an aggressive multi-billion-dollar cleanup of nuclear weapons sites that goes on to this day, and will go on for decades more. He instituted a ban on elephant ivory imports, but his no-net loss of wetlands promise proved to be very, very difficult to keep. And his staff was not always on the same page that he was. Notably, his Chief of Staff - the avidly pro-nuke, pro-oil John Sununu.

CURWOOD: So Peter, what would you say was the crown environmental achievement of George Herbert Walker Bush?

DYKSTRA: His biggest mark is pretty clear to me, and that is clearing the air. The Clean Air Act was originally signed and passed under Richard Nixon in 1970. But Bush's Clean Air Act strengthened the US ability to deal with ozone, to deal with health issues, and to deal with acid rain, which is a problem that is still around in some circles, but has largely gone away and been solved, just like the ozone Hall is known to be closing up these days. Two big victories, both of whom George H.W. Bush had a hand in.

George H. W. Bush’s Presidential Portrait. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about George H.W. Bush's record on the climate.

DYKSTRA: Well, he had a little trouble getting the domestic ball rolling, but internationally, it's been said time and time again that he was strong on foreign policy, and he went to Rio de Janeiro for the first Climate Summit in 1992. He signed the UN Climate document that's gotten the whole ball rolling for the past quarter century on what the world can do in unison on climate change. It wasn't a perfect document, but it's something that today's White House would never consider.

CURWOOD: Indeed, that treaty is meeting as we speak, Peter, in the heart of coal country in Poland. A bit under stress, as President Trump has said that he wants to pull out of the international agreement, the Paris Climate Accord, but still so far, moving forward.

DYKSTRA: President Trump never promised to be the environmental president, which is exactly what George Bush said on the campaign trail. He also went out after his opponent, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis and hit him at home. Boston Harbor had serious pollution problems back then and George Bush, in a debate, said this.

BUSH: That answer was a bad as clear as Boston Harbor, now....

CURWOOD: Well, and Peter course today you can swim in Boston Harbor, and a lot of Bostonians love that song with the line, “love that dirty water”.

DYKSTRA: Well, technically Steve, it's December. I wouldn't want to swim in Boston Harbor right now.

CURWOOD: [Laughs] Agreed. By the way, anything more about George H.W. Bush?

DYKSTRA: Something that has very little to do with the environment directly, but has a lot to do with me personally. As you know I've been in a wheelchair for nearly two years. President Bush signed and was a big advocate for the Americans with Disabilities Act. It's something that I benefit by every day. George Herbert Walker Bush is very much to thank for that law being a reality.

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush updated the Clean Air Act, substantially increasing the federal government’s authority over and responsibility for the environment. (Photo: Carol T. Powers, U.S. EPA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, Peter. And I'm glad President Bush's life touched you as well. And I guess that also suffices for our usual history segment. So I'll simply say that you're an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And thanks, and we'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve. Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on the stories that our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- New York Times | “The Environmental Impact of President Bush”

- Forbes | “The Surprising Climate And Environmental Legacy of President George H. W. Bush”

- Washington Post | “The Energy 202: How George H.W. Bush Helped Turn Acid Rain Into a Problem of Yesteryear”

[MUSIC: The Standells, “Dirty Water” on The Very Best of The Standells, Geffen Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Why politicians can be slow to act on climate change - most registered voters who say it’s a high priority don’t bother to vote.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “St. Mary’s (Nashville tuning)” on Wine, Women & Waltz, Relativity Recordings]

The Environmental Voting Gap

The Americans who care strongly about the environment tend to be young, African American or Latino, and make under $50,000 a year. (Photo: Joe Brusky, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The 2018 Midterms resulted in the election of many environmentally-focused candidates for office at the national, state, and local levels. But to get re-elected, they may have to buck some tough demographics because a majority of registered voters who say the environment is a top priority for them didn’t bother to cast a ballot. To find out who these voters are, and why they might not be making it to the polls as often as other voters, we turn now to Nathaniel Stinnett, the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, based in Boston. He’s on the line now. Nathaniel, Welcome to Living on Earth!

STINNETT: Thank you for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: First, your criteria. Tell us how do you determine if a voter is what you call an environmental voter?

STINNETT: So, we look for the real tip of the spear. We only target environmental voters if they list climate change or some other environmental issue as either their number one most important priority, or their number two most important priority. So, we're going after the real dyed-in-the-wool super-environmentalists. We've identified 20.1 million already registered super-environmentalists. The problem is, even though there are 20.1 million who are already registered, they don't always show up on election day.

CURWOOD: Now, I know you have numbers from the 2014 midterm, about these types of voters showing up. What are those numbers?

STINNETT: So, in 2014, only 4.78 million of those 20 million voters bothered to vote. So, the last midterm elections, 44 percent of registered voters showed up to vote, but only 21 percent of environmentalists. So, there's a big drop off.

CURWOOD: Now, it's fairly soon after the midterms and I'm sure you're still looking and gathering numbers. But so far, what do you see, to get the data on the 2018 midterms?

STINNETT: So you're right, we still are collecting a lot of data. However, we can glean a lot of very good information from exit polling data. So, this is polls taken of people after they left the polls on election day. And what we saw was that a stunning seven percent of voters listed the environment as the single most important issue facing the country. And seven percent might not sound like a lot, Steve. But that's three or four times higher than what exit polls saw just two or four years ago. We had 116 million people vote in these midterm elections in November. So, seven percent of that 116 million is over eight million voters listed the environment as the single most important issue. And that's a pretty big constituency.

CURWOOD: I know this isn’t apples to apples, but if you take this approximation with the data you have, from last time, roughly twice the number of environmentally focused voters came out.

STINNETT: That's right. It's not apples to apples. But clearly, the data shows that something is changing. Either more of our existing environmentalists turned out to vote, or there are some existing voters whose priorities are changing. Maybe they didn't care about the environment two years ago or four years ago, but now they care about it a lot more. There's definitely something changing.

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

CURWOOD: Alright, well, let's talk about this. What do you think kept them home?

STINNETT: You ask a really good question, Steve. And unfortunately, there's not an easy answer to it. But we do know is that people who are likely to really care about the environment are also more likely to be young, African American, or Latino. And those three groups that I just mentioned, historically, vote less often than the overall population. But that's only part of the story. What's really interesting is when we look just at Latinos, the ones who care about the environment vote less often than the other Latinos. Or if we look just at young people, the people who care about the environment vote less often than other young people. So, there's something else going on there. And the truth is, we don't know why these environmentalists aren't voting.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, what's your best guess as to the one or two reasons that are really holding these environmental voters back?

STINNETT: I think part of what's going on here is that political campaigns are in the business of disenfranchising voters. And by that, I mean who you vote for, Steve, is secret, but whether you vote or not, that's public information. That's public record. And so the first thing any campaign does is they look at who votes and who doesn't vote, and they really only spend their time and money talking to good voters. And so right now, all these environmentalists who are saying, “oh, politicians don't care about me”… Well, they're absolutely right. If you have a public record of not voting, why on Earth would a politician care about you? And so I think what's going on here is that politicians make a very clear choice to not spend any time or money talking to, or caring about, people who don't vote. And environmentalists, by and large, don't vote.

CURWOOD: Interesting thought. Any other thoughts about what keeps the enviro-centric voter at home?

STINNETT: I think part of it also goes back to those demographic correlations that I mentioned. Environmentalists are far more likely than other people in the population to be African American, to be Latino, to live within five miles of an urban core, or to make less than $50,000 a year. And what this means is, environmentalists are much more likely to have voting barriers thrown up in front of them. And I think it's important that the environmental movement understand when certain states and certain counties make it harder for minorities or poor people to vote, that disproportionately affects our constituency. That's hurting environmental voters.

Instead of advocating for particular candidates, the Environmental Voter Project focuses on changing the voter base so that a larger number of environmentally conscious voters turn out to the polls. (Photo: ClatieK, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, one thing that you surprise me with in our conversation is that typically people point fingers at the big environmental organizations and say, where are the people of color? And yet, you're saying, those are the people who care most. How do you square that circle?

STINNETT: So, I'm not sure I do square that circle. I think you're absolutely right to point out that the leadership in certain environmental organizations - and I'll say the same thing about the Environmental Voter Project - we do not accurately reflect the constituency that we're trying to serve. I think most people when they imagine an environmentalist think about a yuppie, wearing Patagonia-fleeces, hopping out of their Prius in the suburbs. And maybe that was accurate 20 or 30 years ago, but it's not accurate now. A lot of studies show that the people who are disproportionately feeling the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation are - surprise, surprise - the people who care about it most on Election Day, and these are not wealthy white people in the suburbs. These are African Americans, these are Hispanics, these are people living in environmental justice communities, places where it's hard to breathe, and places that have power plants. These people are the new face of the environmental movement.

CURWOOD: People are looking ahead to 2020, looking ahead to who the Democrats might field. You've worked in political campaigns, you've advised folks from running for everything from city council to the United States Senate. What advice would you offer to any of the Democratic candidates for president, about tapping into what you see as a really underused resource, the environmental voter?

STINNETT: I would say that regardless of what people were seeing in their polls two years ago, or four years ago, the entire landscape has changed. And particularly, when you look at the people who are going to show up in a Democratic presidential primary, climate voters and environmental voters are going to be an enormous constituency. I would go so far as to say, Steve, that maybe 20 percent of the people who vote in the Democratic presidential primary could end up listing climate and the environment as either their number one or number two issue. So, this is an enormous constituency that could be mobilized if someone focused their messaging on talking about climate change. Bernie Sanders is hosting a town hall meeting just about climate change. You're seeing other people like Jay Inslee, Governor of Washington, thinking about running, and he talks about climate. You're seeing Jeff Merkley from Oregon who talks about climate all the time. A lot of people are talking more and more about climate change, and they see it as an advantage. And I just think that's an extraordinary thing to recognize, Steve. I mean, it was only two years ago that we had a whole series of presidential debates and climate change wasn't mentioned once.

CURWOOD: Not once.

STINNETT: Not once. And we're seeing that changing. And politicians aren't stupid. They're not going to talk about something that voters don't care about. So, the fact that so many people who want to run for president are now talking about climate change is a really interesting indication of where they think they can win.

CURWOOD: This may be fairly obvious to some people listening to us, but others may wonder, why is it important for environmentalists to vote?

The turnout of voters who list the environment as one of their top two priorities nearly doubled from the 2014 midterm to the 2018 midterm elections. (Photo: Mark Klotz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

STINNETT: Well, it's important for a few reasons Steve. One, obviously the more environmentalists who vote, the more environmental leaders we will elect. But beyond that, even if you live in a district or a state where you have an incumbent that isn't being challenged, or you live in a dark blue, or a dark red part of the country, it's still important for environmentalists to vote for one very clear reason, and that is this: whether you vote or not, is public record. And simply by voting, you become a first class citizen. Simply by voting, you become part of the unfortunately very small group of Americans who politicians pay attention to, because politicians - surprise surprise - don't care about the opinions of non-voters. They only care about the opinions of voters. So, by voting in every election - local, state and federal - you get to drive policy. You get to tell politicians, hey, look at me, look at my public voting record, I vote and that means you get to drive policy in this country. And that's something that we environmentalists can't pass up.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel Stinnett is founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Nathaniel.

STINNETT: My pleasure. Thank you for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Introduction to the Environmental Voter Project

- The Environmental Voter Project Website

- The Guardian | “‘We Need Some Fire’: Climate Change Activists Issue Call to Arms for Voters”

[MUSIC: Drake, “Passionfruit” on More Life, Cash Money, OVO Sound, Republic, Young Money]

The Right To Repair

Electronics are a rapidly growing part of the waste stream, because devices like smartphones are becoming more difficult and expensive to repair. (Photo: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Wikimedia commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: As we have more stuff, we produce more and more waste. One response to our throw away culture is the Right to Repair, a movement to get people the things they need to fix their stuff. In October, the Library of Congress and the US Copyright Office modified rules to allow consumers to hack into embedded software as needed for repair and maintenance. A major win for the Right the Repair movement, but as Nathan Proctor explains, there’s still a ways to go. Nathan is with the Right to Repair campaign of the Public Interest Research Group. And he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

PROCTOR: Thank you, Steve. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell us about the Right to Repair movement. What exactly is it? And how does it relate to environmental impact?

PROCTOR: Well, I believe that people should be able to fix their stuff. And when you can't fix something, it means that it ends up in the waste stream before it might normally need to go in the trash. And as our world has gotten more and more computerized, it's getting more and more difficult for people to maintain the things in their lives. And this is true of our smartphones and our dishwashers and even of tractors and other ag. equipment.

CURWOOD: Well, we all know what it's like to call a service person and imagine you have a big piece of equipment out in the middle of the field and you're trying to move forward with this planting or this harvest. I imagine the bill just to have somebody come and have them come on a timely basis is going to be fairly steep, as opposed to just simply putting one's own head under the hood and figuring out what's going wrong here.

PROCTOR: Yeah. Most farmers who had their own farm equipment usually had ways to keep that equipment going that was more or less local to them. If they couldn't fix it, there was somebody close by who could fix it. And as these products started getting more and more computerized, there were examples where they took those tools into their own hands in order to execute repairs. And the most famous example now is a set of farmers in Nebraska, who when they were faced with an impossible repair, instead of loading their combine onto a flatbed truck and driving it to the dealership, which would have cost them several thousand dollars, and potentially could have affected their ability to harvest the crops that they were using. The story goes that they hired Ukrainian hackers using Bit Torrent to send broken cracked versions of the John Deere software, so that they could access the same tools that the dealership would use to diagnose and repair a tractor.

CURWOOD: So a few hundred bucks to a hacker instead of a few thousand bucks to the dealer, huh?

The California Farm Bureau Federation reached an agreement with the Far West Equipment Dealer’s Association to increase farmers’ access to parts and software needed for repair. Many criticize the agreement as not going far enough to ensure farmers’ rights to fix their property. (Photo: werktuigendagen, Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

PROCTOR: Yeah, and in 2015, the Library of Congress issued an exemption to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act for ag equipment, specifically saying that farmers had the right to modify software if it interfered with their ability to repair their device. And almost overnight, John Deere updated their terms of service for using a tractor. You know, when you, like, download a new app, you get that 12-page agreement that you unthinkingly hit “agree” on. They updated those terms of service to basically make any modification to the software to be a violation of those terms of service.

CURWOOD: So, just how common is it that consumers can't repair their own stuff? What does that usually look like?

PROCTOR: Well, we know that electronic waste is one of the most rapidly growing parts of the waste stream. And the UN estimates that 60 million tons of electronic waste is generated each year...60 million tons of e-waste would be about 125,000 jumbo jets worth.

CURWOOD: Oh, my.

PROCTOR: And Americans throw out 416,000 smartphones every day.

CURWOOD: Whoa.

PROCTOR: So, we buy these incredible $800 computers, which are very useful. I like to say that on Star Trek, they had five different devices to do the things that one smartphone can do. And we treat them as they're essentially disposable. And this is kind of a new thing that's happening in the world of consumer goods. I mean, 10 years ago, it would be un-thought of to buy a phone and keep it for one year, and then upgrade to another phone.

Nathan Proctor is the Director of US PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign. (Photo: Courtesy of Nathan Proctor)

CURWOOD: OK, so what is it about our smartphones, that we're just chucking them instead of fixing them?

PROCTOR: One of the main problems with our smartphones is that the batteries are very difficult to replace. They are held in with adhesive and the instructions for how to properly switch them out are not being provided by the manufacturers anymore. And the original replacement batteries are no longer being sold by the manufacturer. You have to go through an authorized provider to get that battery service. And a lot of times, if you take it to that provider, they will just try to sell you a new phone.

CURWOOD: In your view, what's the model legislation for a Right to Repair bill?

PROCTOR: So, our model Right to Repair bill includes five things that we think are necessary for repair. We think of them like a five legged stool, which means that if it missing one leg, it's still stable, but it's much more stable with all five legs. And those five things are access to replacement parts, any specialized tools needed for repair, diagnostic software, manuals or schematics, and firmware. And if you have all five of those things, then you can fix it.

CURWOOD: Nathan Proctor is Director of the US Public Interest Research Group’s Right to Repair campaign. Thanks for taking the time today, Nathan.

PROCTOR: Thank you.

Related links:

- US PIRG’s Right to Repair campaign homepage

- Motherboard: “Farmer Lobbying Group Sells Out Farmers, Helps Enshrine John Deere’s Tractor Repair Monopoly”

- Original announcement from the California Farm Bureau Federation on the “right to repair” agreement

[MUSIC: Tab Benoit/Debbie Davies/Kenny Neal, “So Cold” on Homesick For the Road, Telarc]

CURWOOD: Looking for green holiday gifts? The Living on Earth staff has some suggestions just ahead. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chet Baker, “Isn’t It Romantic?” on My Funny Valentine, by Rodgers-Hart, Pacific Jazz Records]

Is Shopping In A Store Greener Than Buying Online?

The CambridgeSide Mall bustles with holiday shoppers. (Photo: Jaime Kaiser)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Tis the season to be ... an online consumer. More holiday shoppers are turning to Amazon and other internet retailers than ever before. But is buying those gifts online a good decision for the planet, or should you head out to a traditional store? Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser went to a Boston-area mall to see how consumers are making the choice.

[MALL SOUNDS]

KAISER: So, the other day I was at the mall doing some holiday shopping, when I found these really goofy socks that I knew my Dad would love. They seemed a little pricey, so I whipped out my phone to see if I could find a better deal. A quick Internet search showed that I could buy them online for five dollars less. Decisions like this one don’t just matter for our budgets or our time. Each purchase knocks the planet too.

[CASH REGISTER SOUND]

So, in terms of climate change, which holiday gifts hit harder -- the ones we buy online, or those in-store purchases? I put this question to a group of mall-goers. It seemed many of them weren’t actually there to shop at all!

MAN: Taking the little guy to see Santa.

WOMAN: I come to the mall usually just to hang around, window shop most of the time.

MAN: I had to come into town for a doctor’s appointment, thought we would just come and wander around. I do my level best to avoid shopping malls anytime in the month of December.

KAISER: Even those who like malls said they prefer to shop online.

WOMAN: I shop online mostly, and I love to come to the malls during Christmas.

A growing number of consumers are opting to have all their holidays gifts shipped right to their front door. (Photo: Global Panorama, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

MAN: We have a baby now, so it’s a lot easier just to do it online as opposed to getting in the car, and then coming to the mall.

KAISER: But the prevailing assumption was that brick-and-mortar stores, were better for the planet.

WOMAN: I’m assuming that shopping here, in the malls, is better for the environment.

MAN: I’m staying with a friend right now and he had a huge shipment from Amazon yesterday, so I was just like, how much waste is there, boxes, and from ordering stuff online, like, I think it’s insane.

MAN: I would think it would probably be more environmentally friendly to go to a mall. Because if you’re ordering online and you’re ordering a half a dozen to a dozen gifts throughout the season, you’ve got trucks going back and forth.

KAISER: The answer? Well, it’s complicated.

If we just focus on carbon emissions, most major studies actually suggest that buying online results in a lower carbon footprint. Research at Carnegie Mellon's Green Design Institute found that if you only shop online, it could lead to a 35 percent reduction in energy consumption. Another study from the UK found that the average trip to the store to buy a non-food item results in 24 times more carbon dioxide emissions than ordering that product online.

But, there are caveats.

Buying in stores might ultimately be the more sustainable option for you, depending on all sorts of variables, like the distance you travel to get to the store, your mode of transportation, and how many other shoppers you’re with.

And, of course, none of this considers all those cardboard boxes for shipping online orders, or supporting local employment.

In the end, I decided to buy those socks from the store. I mean, I already had them in hand, so, why wait? And hey, I’d already burned the carbon to get there.

For Living On Earth, I’m Jaime Kaiser, at the Cambridgeside Mall in Cambridge Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Alternet: Which is better for the environment – Online shopping or going to the store?

- An analysis of the carbon footprint from conventional shopping or online retail

- The Carnegie Mellon Study

Green Gifts For The Holiday Season

Newspaper can be a great alternative to wrapping paper. (Photo: underthesun, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

[MALL SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Are you rolling?

REGO: I’m rolling.

CURWOOD: We're at three two. And then there's one.

[MUSIC: E’s Jammy Jams, “Jingle Bells (Instrumental Jazz)”, Youtube Audio Library, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62HJXjDxL_Q]

CURWOOD: This is Steve Curwood, host and executive producer of Living on Earth and my initials are the same as Santa Claus. So, that means I love giving gifts. And this year my green gifts are two books. One is Sy Montgomery's memoir “How to be a Good Creature”. That's a book you're going to love. And the other is by Gary Paul Nabhan. It’s called “Food From the Radical Center: Healing our Land and Communities”. And really the subtitle should be the title. That is “Healing our Land and Communities”, provocative. And very green! Both of these you will love and be inspired by.

DOERING: My name is Jenni Doering and I'm a producer with Living on Earth. And I recently came across this company called Conscious Step, and what they do is they partner with organizations like Oceana and Conservation International to sell socks that will actually do good. So, they've got socks that plant trees, socks that conserve rainforests, or give books, or protect oceans. The ones that protect oceans have these cool blue waves on them. They've got socks, of course, with little trees on them. And Conscious Step says that the socks that conserve rainforests will actually save 20 rainforest trees from being cut down.

LYMAN: Hi I'm Don Lyman. I do Science Note segments with Living on Earth and so I thought it fitting to suggest science ties for my green gift idea. I've got several science ties: a periodic table of the elements tie, a scientific glassware tie, and my favorite – a herpetology tie with pictures of various reptiles and amphibians on it. People often compliment me on my science ties and ask me where I bought them because they'd like to buy them for people they know who work in science-related fields. I buy my science ties at Harvard University, but you can buy similar ties at various online outlets as well.

O'NEILL: My name is Aynsley O'Neill and I'm a producer here at Living on Earth. My younger brother has always wanted a lion cub. He saw the Lion King when he was a kid and it has been his dream ever since. But he's a high schooler in suburban New Jersey, so it's a bit of an inappropriate gift for him. Instead, what I'll be giving him is a symbolic adoption of a lion cub. I donate money to a conservation fund, they put that money towards protecting animals, and in return, we get a certificate of adoption, we get information about what animal we adopted, and we even get a small stuffed toy.

Although they are cute, lion cubs are not the ideal green gift. But, donating to a fund that protects them might be! (Photo: Tambako the Jaguar, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

KAISER: Hi, my name is Jamie Kaiser. I'm a producer here. So, I was out shopping for a gift for my mom a couple weeks ago, and I was at her favorite store, and I came across a reusable bag. It's called the Stasher bag. It's billed as an eco-conscious alternative to one-use plastic bags and it's made of a food grade silicone that's free of petroleum, PVC, and latex.

BASCOMB: I'm Bobby Bascomb, Managing Producer here at LOE. Almost everyone I know already has enough stuff. So, I try to give experiences instead. In the past, I've given concert and theater tickets, and tickets for sporting events. One year, I got my parents a weekend at a bed-and-breakfast. Now I have kids and for them I like the idea of an annual museum pass or a membership at a play center. But my favorite green gift experience might be a membership to a state or local national park.

REGO: Hi, I'm Jake Rego, Technical Director at Living on Earth. This year I will be giving bamboo smartphone passive amplifiers. These amplifiers require no battery or power supply. Just simply place your smartphone in the box and it naturally amplifies the sound.

MALLOY: Hi, my name is Liz Malloy, and I'm a Producer at Living on Earth. I recently found these cards made by a local artist that feature species native to New England on them. The best part, though, is that instead of throwing them away or storing them in a box forever, you can plant the card in your garden and native wild flowers will grow.

ARENBERG: I'm Naomi Arenberg. I choose the music for each week's show and do the music reporting. When the holidays come, I think about wrapping paper and how the whole concept of gift giving goes back to the origin of the December holidays all around the world. There's a problem though. Wrapping paper, at least in my neck of the woods is not recyclable. And you can see in the week after Christmas or Hanukkah, or any other celebration where you're giving gifts, you can see bins full of paper being thrown away and going to landfills. So, wrap your gift in a sock, maybe one of the socks that Jenni mentioned. Wrap your gift in a beautiful kitchen towel. If one kitchen towel isn't big enough, tie some interesting knots, tie a few together. You’re creative, I know you can do this! Happy holidays.

CURWOOD: Happy holidays.

DOERING: Happy holidays.

LYMAN: Happy holidays.

O'NEILL: Happy holidays.

BASCOMB: Happy holidays.

REGO: Happy holidays.

MALLOY: Happy holidays.

Related links:

- More green gifts ideas

- And, for even more eco-friendly gift inspiration

- Living on Earth archives: “Shopping for eco-gifts”

Smeagull The Seagull: A True Story

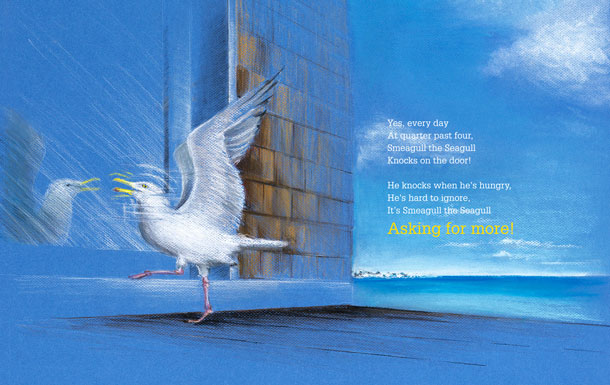

Smeagull the Seagull comes to the house near the shore every day and knocks on the sliding glass door. (Illustration by Valerie Elaine Pettis)

CURWOOD: You may have noticed Mark Seth Lender, our Explorer in Residence, was missing from our holiday gift ideas segment. Mark brings us evocative essays from his travels with stories of lions hunting on the Serengeti or close encounters with polar bears in the Arctic. But his gift for this holiday season is his experience with wildlife much closer to home, literally in his back yard. Mark will be giving a book for children he wrote and his wife Valerie Elaine Pettis illustrated, about a herring gull that visits his Connecticut home every day looking to be fed, of course. So to preview our holiday storytelling season, here is Mark reading his book, Smeagull the Seagull.

LENDER: There's a house near a seawall, facing the shore, and that house has a porch with a sliding glass door. And the people who live there, Valerie and me, stand by that door and look toward the sea.

Smeagull The Seagull is available now. (Illustration by Valerie Elaine Pettis)

Because Seamgull the Seagull knows that we know. He comes in the rain. He comes in the snow.

He comes in summer, I'm telling the truth. He comes when icicles hang from the roof.

He comes in the spring. He comes in the fall. He comes when it's cloudy, and there's no sun at all.

Yes, every day at quarter past four, Smeagull the Seagull knocks on the door. He knocks when he's hungry. He's hard to ignore. It's Smeagull the Seagull, asking for more.

Again in the morning at 10 past 6, Smeagull comes knocking. It's loud is a stick when he knocks with his beak on the sliding glass door. It's Smeagull the Seagull, asking for more.

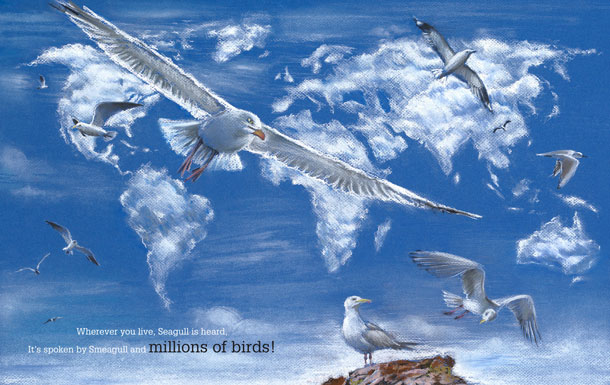

Wherever you live Seagull is heard. It’s spoken by Smeagull and millions of birds.

I can say I'm tired and I'm going to bed.

I can say I'm hungry and I want to be fed.

I can say I'm angry, angry and mad.

I can say please. I can say I'm so sad.

The book is based on the story of the real “Smeagull” who would often greet Mark and Valerie at their Connecticut home. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Some people think they're smarter than birds. But can they speak Seagull? Not one single word.

I was talking and talking. I was all out of breath. So I started knocking, knocking works best. My people know when I knock on the door, it's Smeagull the Seagull, and I'm here for more.

I only eat fish from the Starfish Store. I'm a star, named Smeagull, and I'm ready for more.

Smeagull the Seagull walks down the beach. He lands on the seawall, he flies out of reach. All of the children, all over the town cry, there goes Smeagull! Smeagull’s around!

All that walking and flying keeps Smeagull fit, but it does make him hungry, and he eats quite a bit. So we bought a new freezer, with a really big shelf. Full of fish, for Smeagull, it's all for himself!

It stands in the kitchen from ceiling to floor. We thought we'd be ready when Smeagull said, “more.”

Then Valerie cried “Where’s Smeagull’s fish! The shelf is empty. There's no food in his dish! Starfish will be closing in a minute or two.”

I said, “Start the pickup!” Down the driveway we flew.

Captain Mike had the keys. He was locking the store. He was fresh out of fish. But he said, “I’ll get more.”

Hungry for scraps of sustainable seafood, Smeagull visits even in a snowstorm. (Illustration by Valerie Elaine Pettis)

So he climbed aboard his boat, the Collette, named after his wife who keeps Starfish as pets.

“Don't worry, he said we're not finished yet I'll head out to see, and see what I get.”

The engine roared. He was soon out of sight. “If we have to,” we called, “We'll wait here all night.”

Captain Mike returned with a net full of smelts. “They're fish” he said, “they’re good for your health.”

And he gave us enough to fill Smeagull’s shelf.

We drove home in the pickup with our fish neatly wrapped. Smeagull didn't greet us, was he taking a nap?

All we could do was shake our heads.

“We have to find Smeagull,” was all that we said.

All of the children all over the town helped look for Smeagull. They looked up, they looked down.

They looked in the trees. They looked on the ground. But Smeagull The Seagull was not to be found.

We were tired and hungry, but we couldn't eat. We turned off the lights, but we couldn't sleep.

It was cold, and windy, and day after day, we waited for Smeagull but he'd gone away.

The sea cannot hear you. The sky cannot speak. Life without Smeagull is lonely and bleak.

But what is that sound I here at the door? That knock, it’s familiar! We ran cross the floor.

“I'm Smeagull The Seagull. I'm back with my seagull. Her name is Shegull. She's a seagull like me. There's an egg in our nest and we’ll soon be a family of three.”

The calls of the gulls are a familiar sound not only at the coast, but far inland. Seagulls are found on every continent including Antarctica. (Illustration by Valerie Elaine Pettis)

There used to be one gull and now there are three gulls. Smeagull, Shegull, and baby gull Megull.

They're our family birds and we love them too much for words.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s explorer in residence Mark Seth Lender, reading his new book Smeagull the Seagull. You can find out how to get his book, and see photos of the real Smeagull, on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Buy a signed copy of Smeagull the Seagull and support Living on Earth

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Sierra Maestra, “Sangre negra” on Sonando Ya, by Eduardo Himely, World Village Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, the creation story of planet earth.

STEWART: Our nearest neighbor, our partner in space -- the Moon -- is a key part of that story because it set the ending of Earth's growth, and the beginning of our climate.

CURWOOD: Studying the moon to understand the genesis of our planet. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Nora Jones, “Cold, Cold Heart” on Come Away With Me, by Hank Williams, Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. Also, you can find us on instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth