February 8, 2019

Air Date: February 8, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Toxicants in Diapers and Sanitary Pads

View the page for this story

An international team of scientists tested single-use diapers and sanitary pads for toxic chemicals, and has discovered phthalates and volatile organic compounds in every brand tested. These chemicals are known to cause a variety of health complications, including birth defects and endocrine disruption. Jodi Flaws, a co-author on the paper, joins Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb to talk about these toxic substances and how they impact health. (10:34)

A Green New Deal For All

View the page for this story

Support for a “Green New Deal,” drafted by freshman Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Senator Ed Markey (D-MA), is solidifying among environmental groups. Over 600 of them recently signed a letter calling on Congress to bring forth Green New Deal legislation, to create jobs as well as alleviate environmental health risks for vulnerable communities. Vien Truong is the CEO of Green For All, one of the groups that signed on to the letter. She talks with host Steve Curwood about why environmental justice and economic justice go hand-in-hand. (08:35)

Bangladesh’s Climate Migration Crisis

View the page for this story

In Bangladesh, hundreds of thousands of people are being displaced from their coastal homes, and are moving into the slums of cities underprepared to handle this crisis. Journalist and 2018 National Geographic Explorer Tim McDonnell talks with host Steve Curwood about the climate migration crisis in Bangladesh. (10:55)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood this week to discuss how history is repeating itself on America’s public lands, as the pro-extraction Trump Administration mirrors actions taken by the Reagan Administration in the 1980s. Also, a recent study from the University of Southern California links traffic pollution to a junk food diet. Finally, a look back to celebrate the 160th birthday of scientist Svante Arrhenius, who published one of the first definitive papers on the greenhouse effect. (03:46)

Neighborhood Burn Squads Fight Fire With Fire

View the page for this story

California communities nestled among the forested foothills of the Sierras are vulnerable to wildfire, and some communities are taking steps to reduce their risk. Nathanael Johnson, a senior writer for Grist, witnessed a neighborhood burn squad in action in his hometown of Nevada City, California, and he tells host Steve Curwood about the potential benefits, and risks, of these community-driven controlled burns. (13:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jodi Flaws, Nathanael Johnson, Tim McDonnell, Vien Truong

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A new study has found concerning levels of toxicants in feminine hygiene products and paper diapers.

FLAWS: Some of these chemicals can interfere with the nervous system, and can lead to potentially cognitive and behavioral problems. Outside of the reproductive system, almost any endocrine system you can think of, these chemicals have been shown to have a negative impact.

CURWOOD: Also, sea level rise, more powerful storms and saltwater intrusion are forcing people to abandon their homes in low lying parts of Bangladesh

McDONNELL: That's where you start to see these climate impacts bleed over into economic impacts. And it starts to kind of blur the line between people who are climate refugees or disaster refugees and economic migrants.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Toxicants in Diapers and Sanitary Pads

Volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, and phthalates were found in fifteen different brands of single-use diapers and sanitary pads. (Photo: Jim Makos, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Feminine hygiene products and paper diapers may expose women and children to dangerous chemicals, a study based at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has found. The study came in the wake of a 2017 class action lawsuit joined by more than 15,000 women in South Korea. They alleged the maker of Lilian sanitary pads caused health problems including skin rashes, painful cramping and irregular bleeding. The Illinois team sampled a variety of pads and paper diapers and found phthalates and volatile organic compounds, or VOCs in every brand they studied. Professor Jodi Flaws is part of the research team and we asked her to share some of the findings and how the research was done. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

FLAWS: So, we went about the research by gathering different brands of sanitary pads, and in a scientific manner, taking samples from each of these different brands, and then using those samples to measure the levels of volatile organic chemicals that were in each of the different brands. And we looked both at what's in the brand as well as what was in the air surrounding the packaging of the brands. And what we found were that all of the brands did contain some levels of volatile organic chemicals, and the levels varied quite a bit by brand, and the types of chemicals that were in the brands also varied.

BASCOMB: And, what are some of the health implications of exposure to volatile organic compounds?

FLAWS: It depends on the level of exposure, and the route of exposure, but many of these compounds have been shown to have reproductive effects, such as abnormal menstrual cyclicity. They’ve been shown to have problems with allergic reactions, skin irritation, some issues with changing the levels of women's sex steroid hormone levels as well.

BASCOMB: And you also looked at phthalates. Can you tell me about that?

FLAWS: Yes. So we looked at phthalates because phthalates, in many studies now, have been shown to be reproductive toxicants. In both animals and humans, phthalates can alter hormone levels, they can reduce fertility, they can cause some problems with the ovaries and the uterus. And in our study, we did find that these brands that we selected all had measurable levels of phthalates.

BASCOMB: And phthalates are an endocrine disruptor. Can you tell me a bit about the concerns associated with that?

FLAWS: Yes. So, endocrine disrupting chemicals are chemicals that can interfere with any aspect of hormones, either the production of hormones, the action of hormones, the function of hormones in the body. And some of these chemicals can interfere with the nervous system and can lead to potentially cognitive and behavioral problems. Many of these chemicals have been shown to interfere with thyroid function and lead to problems with metabolism. And they've also been shown to affect the pancreas, so there could be some concern about diabetes. And several of the chemicals are what we call obesogens, which have been linked to obesity, and so outside of the reproductive system, almost any endocrine system that you can think of, these chemicals have been shown to have a negative impact.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. And, sort of the insidious thing about phthalates, I mean, the dose doesn't make the poison. So it's a very specific exposure that can cause problems.

FLAWS: Correct, and actually a big concern with a lot of these endocrine disrupting chemicals is that the dose doesn't make the poison. It's not always the higher doses that we need to be concerned about. Sometimes the really low doses can have the most profound effects. So, it really does matter what the dose is and we can't just assume, because it's a low dose, that it's a safe dose.

BASCOMB: And the people using these products, I mean, we're talking about babies and women of reproductive age. Those are some of the most vulnerable people in our population. Can you talk to me a bit about how chemical exposure in those groups is a concern?

FLAWS: It's a concern in adult women for a couple of reasons. So, one, if the chemicals are in the sanitary pads, there's potential for chronic exposure, because if you consider that most women will have a menstrual period at least once a month, and they're wearing these for several days of that month, from puberty until the time of menopause. And so there's potential for long-term exposure. The other issue is that the pads are placed in the genital area, which is a very sensitive area, and the skin there is quite thin, so it's pretty easy to absorb volatile organic chemicals from that area. And with babies, I would say there is a concern because baby skin is very sensitive and very thin. And it's easier to absorb chemicals through baby's skin than probably some adult skin, depending on that the age. And so there's concern about there being chemicals that are right in the areas, which would be sensitive in the babies as well.

BASCOMB: And why might these chemicals be found in these products to begin with? What's their function?

FLAWS: So these products, both diapers, and sanitary pads, are made to be absorbent, and so some of these chemicals might be in the materials that are used to make products more absorbent. These chemicals can also be found in plastics and so, some of the containers or packaging, they're made out of plastic. And some of the barriers include some of these plastic linings, which could also contain the chemicals.

BASCOMB: Now, phthalates are in a lot of products, they're in plastic toys and things that babies might put in their mouths. How did the levels that you found in these products compared to other ways that people are exposed to phthalates?

FLAWS: So, it runs a quite a big range. So depending on the phthalate, we've got levels that are quite different. But in general, some of these levels that we're detecting are much higher than from exposure through other routes. So, one of the particular phthalates, it's about a 6000-fold increase in exposure than what has been documented in other routes of exposure. So, I think the levels can vary quite a bit, depending on the type of exposure, but a lot of these, we're seeing higher levels than have been reported from other types of products or exposures. We were actually pretty surprised to find such a large range. To us, that meant that the products are all being manufactured possibly in different ways, or packaged in different ways. But having said that, given the abnormal dose-response curves that happen with some of these chemicals, we can't just always assume that a low amount is better. What we need to figure out is which levels of chemicals could be harmful, and then try to make sure that we could design products that either don't have the chemicals at all or have levels of chemicals that are not going to cause harm.

BASCOMB: You said there's a very wide range in your study. Some brands have relatively low levels, and others very high. Why didn't you name which brands are more concerning?

FLAWS: Partially because it would get into some legal issues that we’re not prepared to handle, and also some scientific journals actually have restrictions on writing about specific products. Also, I think my colleagues and I wanted to err on the side of being a little bit cautious in that, this is probably the first study to really look at this issue in a scientific manner. We want other people to test these products and be certain before we say something is, you know, bad because we don't want to put a certain product in jeopardy or make a certain product sound really good when we've only got one study now measuring these things.

BASCOMB: Well, what can you say to someone who's listening right now and concerned about what products they're using? If you're standing in the aisle in the grocery store and trying to choose a brand, choose a product, what should they be looking for? What should they be doing?

FLAWS: So, I think that one thing they could do is look, possibly, to make sure that when they buy the products, to maybe open up the wrapper and let the product air out for a while, because these chemicals are volatile. And so it is possible that you could get rid of some of it by just letting the product air out. The other thing is, maybe, if it were me, I would be choosing products that might not be the most absorbent products. In the Korean TV report, what was happening is women there were choosing products that were super, super, super absorbent and had gels in them. And so, I think those products are probably on the tail end of the spectrum where they caused a lot of problems. And so, picking products that don't contain those kind of gels and don't have a strong smell.

BASCOMB: And I mean, there's other products, there's the menstrual cup, and then, of course, there's reusable diapers. Are those things that you think people should look into?

FLAWS: Yes, absolutely. As far as the babies, I would say that cloth diapers would be a really healthy alternative to looking at that. And yes, you're absolutely right the menstrual cup is an option for women to consider.

CURWOOD: Jodi Flaws, professor of Comparative Biosciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb. According to the Korean Herald, on December 7, 2018, Procter & Gamble Korea decide to withdraw their sanitary pad “Whisper” from Korean shelves due to the controversy. But US press representatives for Proctor and Gamble have declined to comment. There is a link on our web page to an article in the Korean Herald that names some of the other companies investigated by regulators in Korea.

Sanitary pads and tampons are considered medical devices in the US and come under the purview of the federal Food and Drug Administration, but we were unable to get a comment from the FDA.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “How Diapers and Menstrual Pads Are Exposing Babies and Women to Hormone-Disrupting, Toxic Chemicals”

- Click here to view the original article in Reproductive Toxicology

- The Korea Herald | “Lilian to Refund All Sanitary Pads”

- The Korea Herald | “P&G Korea to Pull Out of South Korea’s Sanitary Pad Market”

- Cosmopolitan | “9 Organic Pads Your Bathroom Cabinet Needs”

[MUSIC: The Winter’s Tale Ensemble, “The Argument Of Time” on The Winter’s Tale, by Michael J. Veloso, published by Michael J. Veloso]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Saving the climate while saving family incomes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Grisman Quintet, “Desert Dawg” ]

A Green New Deal For All

The solar energy industry can create jobs through the manufacture as well as the installation of solar panels. (Photo: Fort Dix / U.S. Army Environmental Command, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

About half of families in the US have savings of less than $500, and virtually all of the US is at risk from pollution and the deleterious effects of climate disruption. So to boost the economy and protect the environment at the same time, some 600 progressive economic and environmental advocacy groups are pushing for a Green New Deal. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts are both Democrats working on a draft resolution for Congress. They say the US needs "a national, social, industrial and economic mobilization at a scale not seen since World War II." Green For All is a member of this coalition in Oakland, California. It calls for a green economy to help lift people out of poverty. Vien Truong is CEO of Green For All and she joins us now, Welcome to Living on Earth!

TRUONG: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So first tell me, why is your organization, Green For All, pushing for a Green New Deal?

Vien Truong is the CEO of Green For All (Photo: Courtesy of Green For All)

TRUONG: We've been pushing on this for a while, since 2007. And it's because our leaders and our people know both the dual problems of pollution and poverty are especially hurting low-income communities and communities of color. So Green For All has been pushing for a new economy, a new green economy strong enough to lift people out of poverty. And that's the work that we're doing, and that's what work we're excited to pick up and continue doing as part of the Green New Deal.

CURWOOD: Vien, I understand that environmental justice is something that's pretty close to your heart. Tell me about your experiences and how they shaped what drives you now.

TRUONG: Yeah, I grew up in Oakland, and I'm the youngest of 11 kids. My family came here from Vietnam after the war, as part of the boat people refugees. And the first jobs they could find were working on farmlands as migrant farm workers, picking strawberries and snow peas, in these toxic fields. And then they graduated to working in sweatshops in Oakland, during the crack years. We lived in a community where one out of four people had asthma, where our schools were going from neglected to dangerous, where most of my friends were in and out of jail or dropped out. The local newspaper once created a mapping system to look at what the life expectancy is for people in my community versus others. And they saw that people who lived in my zip code, 94601, were living 12 years less than people who lived in a more affluent community just seven miles away. And so for me, it is an urgency around how do I make sure that my kids don't get robbed of their 12 years just because of where we live, or because of the zip code in which we're in? And not only am I doing that for my kids but people who live in communities like mine across this country.

Vien Truong’s hometown of Oakland, California is a network of freeways that pollute the air of low-income communities. (Photo: Rodrigo Soares on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Now, briefly summarize, what is the pitch here, how do you protect the environment, at the same time, have more sustainable lives for people?

TRUONG: It's easy, you know, solar panels don't put themselves up. Smart batteries, wind turbines can't manufacture themselves. We can create jobs in creating solar panels and installing them on rooftops, we can create jobs in the Midwest, in areas that have been de-industrialized, post-industrialization, in building the turbines, building the smart batteries and smart technology. We also want to see smart grids, we want to see more investment into safe homes and housing, through energy efficiency, through making sure that we have the right materials in our homes that are non-toxic, we want to make sure we're investing in the local businesses and local communities. That's the exciting part of the Green New Deal for me. The opportunities that goes from helping to invest in small independent farmers to help us with planting crops that actually pulls carbon out of the air, and make sure that we're growing foods and vegetables and sequestration in our country, to making sure it's smart manufacturing; to making sure that we are actually creating economic diversity across the country, I think that's the opportunity in the Green New Deal here.

CURWOOD: Now, recently there was a letter that some hundreds of, actually of different environmental groups signed, saying that, hey, when it comes to a Green New Deal, they don't want to see market-based mechanisms and certain technology options. So when they talk about market-based mechanisms, they're talking about carbon and emissions tradings and offsets, that sort of thing. Sounds like you see more nuance there.

TRUONG: You know, I think if we're really looking at the scale and the level of the Green New Deal that we need to be at, in order for us to have a sustainable future, then we got to make sure that we're looking at all of the tools and all of the policy options that we need to in order for us to fund it. The way that I read the letter, which by the way we signed on to and support, is that the hope is, we've got to make sure that we're getting to the green new future, the Green New Deal in ways that is just and equitable. And for too long, these carbon pricing schemes have been schemes. They have been manipulations of what is a good intent, around getting to a green policy, but hiding the devil's in the details, which then creates continuous pollution, aggravating the problems in low-income communities like the one that I live in. And so we want to make sure that that doesn't continue. And I think the intent of the letter is to say, let's make sure that we get to a just transition to get to the future that we want to have.

CURWOOD: So how would you get these market-based mechanisms to be just?

TRUONG: Well, I think we have some examples of them across the country. One that I worked on is in California, where we help to shoot at some ambitious policies around getting to 100% renewable energy, around making sure that we're reducing our pollution to 1990 levels by 2020. And then in California, what they did was have a carbon pricing program -- in this case, it's cap and trade -- and use the investments that are generated from having big polluters responsible to clean up and then pay up and then investing that money into solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate clean technology. Now, let me just say, I don't think that the policy is perfect in California. And there's a lot of room for growth. And what we're beginning to worry about now is where and how we can begin to actually invest even better in the communities that have suffered from pollution. And I think as we're beginning to improve on the California model, we also have to begin not just to throw the whole thing out, but figure out how in the national level we learn from those lessons and improve upon it at the federal level, and then in states across the country.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think the Green New Deal will enter into the 2020 general election race? How should it enter into this upcoming political contest?

Truong is cautiously optimistic about the usefulness of carbon trading as a tool for combating climate change. If implemented poorly, she says, it can end up reinforcing environmental injustices like the siting of polluting industries near low-income communities and communities of color. (Photo: Patrick Hendry on Unsplash)

TRUONG: We're now in a place where we have the clean technology, we have the science, we have the facts, but what we don't have is the political will necessary to really deploy the solutions at the scale that we need. And we need to continue demanding our elected leaders, our politicians to stand up and to be bolder, like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to continue to push for and represent our communities and not Big Oil. At the state and local levels, state leaders, governors have a huge amount of opportunity for them to lead on the fight, to show us how it's done. California, Washington, Oregon, New York, Colorado, we've begun to see great leadership at the elected leaders level, I think we can see even better and maybe more competitive levels of leadership from our private sector. I think that would be exciting to see businesses step up even further as they did during the Paris Climate Agreement negotiations. I think there's a role for them to play here now. I also think that it would be important for us to be calling for a debate on climate change. We're hearing more and more people now declare they're going to run for president, they're going to run for president. That's great. That's fantastic. Now, I would love to see not only people declare that they want to be president, but why they want to lead and what kind of solutions they're going to be leading on. And I think climate change is a huge problem. And I would love to see a debate on climate change that in each of the debates for them to address how they're going to tackle one of the biggest problems that we're faced with now globally. And then finally, I think for us, people who care about the issue and want to get involved, they can join us in however ways they want to contribute to the solution where there's policy, whether it's with your artistry or whether it's different things. There's a lot of things people can do, but I think it takes all of us now and now is the right time.

CURWOOD: Vien Truong is the CEO of Green For All. It's a nonprofit focused on building a green economy that can lift people out of poverty. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

TRUONG: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Green New Deal Letter to Congress

- The Green New Deal House Resolution text

- Vox | “The Green New Deal, explained”

- About Green For All

- New Republic | “Some of the Biggest Green Groups Have Cold Feet Over the ‘Green New Deal’”

[MUSIC: Sinead O’Connor, “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” on I Do No Want What I Haven’t Got, Chrysalis Records]

Bangladesh’s Climate Migration Crisis

Flooding is a major issue in Bangladesh that affects thousands of people’s lives. (Photo: Flickr, Climate Centre CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate disruption already has millions of people on the move

forcing entire communities from their homes. And perhaps no population is more imperiled than the people of Bangladesh. Nearly 80 percent of Bangladesh sits in a flood plain, near the rising seas. More frequent strong storms have meant even more flooding and saltwater intrusion for a country that is already routinely flooded during the monsoon season. National Geographic writer Tim McDonnell recently traveled to Bangladesh and joins us now from Washington D.C. Thanks for joining us, Tim!

MCDONNELL: Great to be here, Steve. Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: Tim, what exactly is happening in Bangladesh that's leading to this climate migrant crisis for people living along the coast?

MCDONNELL: So, Bangladesh is one of the world's most vulnerable countries to climate change. And, it's experiencing a pretty wide range of different impacts everything from riverbank erosion that is increasing because of ice melting in the Himalayas, that's coming down through rivers in Bangladesh, increasing the volume of water there and leading to erosion. They have, of course, tropical storms and cyclones that affect people. They have regular flooding. They have an increase in saltwater intrusion in the coastal areas because of sea level rise, that's poisoning crops and fishing areas there. And, in fact, in the north of the country, they also experience drought. So they really get all of these different impacts. Bangladesh, being a very densely populated country, a lot of the times these impacts lead to people being displaced in one way or another

CURWOOD: As I understand it a lot of people who have been affected by this climate disruption are moving into Dhaka that's the capital city of Bangladesh. But, you report that they're not exactly finding solace instead they're getting stuck in slums and working in difficult hard labor jobs. Just how well is Dhaka doing at receiving this inundation of people and what are they doing to adjust to this population increase?

MCDONNELL: Well, Dhaka is really I think out of its depth. And I spoke to everyone from 'course migrants themselves to scientists, urban planners, really a broad range of different people who are involved in this space. And there was pretty much universal agreement that the city is beyond its capacity. They have thousands of people arriving there every day. Not all of those are climate change migrants, of course, but many of them are. And actually, 40% of the city's population lives in slum areas. You know, the city really has very little in the way of affordable housing. It's really not prepared for this influx at all. And so people are kind of finding housing anywhere that they can. On the fringes of construction sites, in the kind of backyards of skyscrapers. I visited one slum community that the land had actually been built from scratch over what used to be a lagoon. People had filled in a lagoon with sand and then kind of built a new community on top of that. So, you know, people are really just kind of looking for any place that they can stay. But it's it's happening all in a very kind of helter-skelter, unplanned sort of way that creates a lot of problems for people living there. They have a problem with human trafficking. So it's kind of security, health, utilities, basic living conditions, all of these things are really negatively affected when you have so many people coming in, in such a kind of unplanned way.

CURWOOD: And, we should mention that this is a bit of a perfect storm, because along with the climate disruption, there are all these folks who are being forced to flee out of Burma if they are from the Rohingya group. And I imagine that's had a huge impact as well.

MCDONNELL: Definitely. And what's really interesting about that crisis to is that it's sort of a double crisis. You have refugees who are fleeing into Bangladesh, because of that Rohingya crisis. They're finding relative, you know, kind of safety in Bangladesh, but then also moving into areas that are again, highly exposed to climate change, mudslides, flooding, that sort of thing is really a problem for those Rohingya refugee settlements. And that's something that I think is something that really needs to be looked at closely all around the world, is not only how climate change is prompting migration or prompting refugee crises, but is creating additional problems for, you know, migrants or refugees who maybe move because of violence or other forms of persecution. They may be exposed to climate change impacts in the place where they arrive. And certainly, that is happening in Bangladesh.

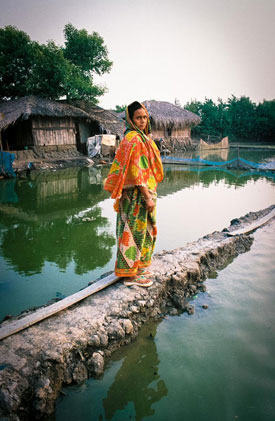

Forida Khatun stands behind her house in Gabura, Bangladesh, in November. Two of her sons migrated to Dhaka after the family home was destroyed by storms multiple times and agricultural jobs were lost due to salinity intrusion. “Only Allah can save us," she says. "We don’t have any power to save our children.” (Photo: Tim McDonnell)

CURWOOD: So, there are monsoons there in South Asia, it's nothing new to Bangladesh. People there time and time again, survive sometimes horrific monsoons and rebuild. What's changed what's different now?

MCDONNELL: There's a few things that are different. In some cases, the impacts that people are experiencing are new. For example, this kind of saltwater intrusion that I mentioned. Because of sea level rise, salt water coming into coastal areas that are really predominantly agricultural. People have fish farms and rice paddies there and salt water has had a huge impact on people's ability to grow crops and fish in that area. And there was a study that actually just came out in November, indicating that in the next few decades, hundreds of thousands of people could be displaced just because of that salt water impact alone. So, that's a kind of new impact. In other cases, as you mentioned, some of these impacts are things that people who have been living in this Ganges River Delta have been dealing with for 10s of thousands of years. Riverbank erosion is nothing new. Tropical storms are not new. You mentioned the monsoons, of course, not new. But it's really the rate that these things are happening and the kind of scale of impact. And, also, one thing that climate change does is it tends to disrupt the rainfall patterns, the seasonal rainfall patterns. So, you're getting rain at times, when you don't expect it, you're not getting rain at times when you think that it should be coming. So it's really throwing off the course of the monsoon, sometimes strengthening the monsoon. So it's just kind of throwing a wrench in all of the works of these natural cycles that people are used to. And then, of course, in the background of that, you have really high rates of population growth. So at the same time that these environmental catastrophes are happening, you just have more people who are exposed to the challenge. And that leads to an increase in the level of displacement.

CURWOOD: So, if the weather systems are messed up, how are people eating? How are people able to grow the food they need?

MCDONNELL: One thing that you see in the coastal regions that I visited was people switching rice paddies over to shrimp farming, which tends to be a little bit more tolerant of the salt. So, people kind of are experimenting with different ways of growing crops, I met a few farmers who are experimenting with trying to grow salt-tolerant rice. So, there's a kind of science and adaptation element here where people are looking for new opportunities, you know, trying to kind of fill in where they can. One of the problems with shrimp farming, interestingly, is that it's more tolerant to salt, but it employs far fewer people. You could have one shrimp farm that, you know, the same area, if you are growing rice, you could maybe employ 100 people. For shrimp farm, you're just employing one or two, it's very kind of low maintenance. And, again, so that's where you start to see these climate impacts bleed over into economic impacts. And it starts to kind of blur the line between people who are climate refugees or disaster refugees and economic migrants.

Due to saltwater intrusion, many farmers in Bangladesh are converting their rice patties into shrimp farms which are more tolerant of salt. (Photo: Flickr, Amir Jina CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How did you feel seeing all this?

MCDONNELL: Well, it was-it was really disturbing. The way that one person described it, kind of local leader in one of the coastal areas that I went to, is that this kind of migration, the loss of people in these coastal communities, what the way he said it is that it leaves a hole in the heart of the village. So people, I think, really feel kind of emotional strain from losing their family members, obviously, and people feeling like they're really kind of starting to lose faith in their ability to maintain a life in this coastal area that they have called home for generations. I mean, no one wants to leave. In all these cases, you know, I didn't meet a single person who said, "I'm really excited to get to go try my luck in Dhaka." This is always a very painful choice for people. But at the same time, I found that people in Bangladesh were really up for trying to adapt the best that they can. One scientist I interviewed said Bangladesh might be one of the world's most vulnerable countries to climate change, but it's also one of the most ready to adapt. People here have been kind of living with environmental catastrophe for generations and generations.

CURWOOD: By the way, how close to sea level are these coastal towns within Bangladesh, and how much has sea level been rising for them?

MCDONNELL: In some places that I went to, I talked to one local leader who told me that in his area the high tide has been coming up by about a foot a year for the last several years. So that's, you know, it's really quite an alarming rate of sea level rise. In the coming decades, you know, you're going to see a lot of area that is just totally submerged. Permanently, year round. So that's just something that people are kind of having to deal with now, is that looking forward to that kind of future.

CURWOOD: Looking ahead, how much of Bangladesh will potentially, well, just become uninhabitable?

MCDONNELL: Yeah, so there was a study that was done that found that because of sea level rise, the land on which more than 800,000 people currently live, is expected to be permanently submerged by the year 2100. So I mean, that just really shows you the level of change that's happening. Hundreds of thousands of people, the land that they're currently living on, is going to just be permanently underwater. And that's really just only, you know, a kind of piece of the pie because you have all these other factors like storms, saltwater intrusion, that are simultaneously displacing other people. You know, it's all of these factors that come together, that's how you get up to this number of more than 13 million, which is what the World Bank prediction for the number of climate migrants in Bangladesh by 2050.

CURWOOD: So, people sometimes say that the Bay of Bengal, where Bangladesh is, is the canary in the coal mine for what the risks that civilization is running with climate disruption. How fair is that?

MCDONNELL: I think that's very true, actually. A country like Bangladesh really encapsulates a wide number of the risks that climate change poses to all different parts of the world. All these things that are prompting kind of human migration. And when you look at Bangladesh, especially, you see what happens when you have this kind of unprecedented level of human mobility. You have this unchecked rampant urbanization that's a problem. You have risk for all sorts of vulnerabilities, health problems, human trafficking, all these other things that people have to face there. And it really encapsulates the challenge that lots of different countries are going to face moving forward. And that's why it's so important now, at this stage for world leaders to become more serious about dealing with this climate change and migration nexus. Figuring out ways to provide safe passage for people. Getting more serious about what this crisis is going to look like and what we can do to try to ease, you know, life for people who are affected by this.

CURWOOD: Tim McDonnell is a journalist and National Geographic Explorer. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Tim.

MCDONNELL: My pleasure, Steve. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- More stories by Tim McDonnell

- National Geographic | “Climate Change Creates a New Migrant Crisis for Bangladesh”

- World Bank’s Assessment of Bangladesh’s Climate Crisis

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Mo Drums” on Entrain Live: Vol 1, Rise Up]

CURWOOD: Coming up – fighting fire with fire. Literally. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Art Blakely, “Moose the Mooche” on Drums Around the Corner, by Charlie Parker, Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Beyond The Headlines

Utah’s Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. And with me now on the line from Atlanta, I think, is Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN dot org and DailyClimate.org. Are you there, Peter?

DYKSTRA: You think, therefore I am. How you doing?

CURWOOD: Good. All right. Well, I want you to tell us about what's going on beyond the headlines. What do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, back in the 1980s, a very controversial Secretary of Interior for President Reagan, James Watt, became known for laying out oil and gas leases offshore and on land without checking with the oil industry to see if there was any interest in leasing them. And a lot of times, they're just wasn't. There's kind of a rerun of that going on now in public lands in Utah. The Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument created by President Clinton under the Antiquities Act was reduced by President Trump, largely so that some coal interests and copper mining interests could get into areas that they had expressed mining interest in, in the past. Turned out there was no interest in the very low-grade coal that was available there. And now a copper mine that was proposed by a Canadian company has been dropped because the company's out of money.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's right. Remember copper just makes pennies, there's not a lot of dough in it these days.

DYKSTRA: Not a lot of dough. You know, all of this is part of the legacy of Watt's spiritual successor, Ryan Zinke; he resigned in December in a cloud of controversy. And this week, President Trump announced he'll nominate David Bernhardt, who was Zinke's assistant; and unlike the replacement at EPA for the scandal-plagued Scott Pruitt -- Andrew Wheeler over at EPA was a former coal lobbyist -- but David Bernhardt, likely to be Interior Secretary, is actually a former oil lobbyist, so there's a big difference there. He had also worked to lobby for copper miners in the past.

CURWOOD: You know, you need diversity among your crew. What else do you have for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Ah, well there's a study from the University of Southern California, suggesting that there could be a link between early exposure to traffic pollution and a fondness later on for a junk food diet. This was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition based on a previous study on animals that suggested that exposure to diesel exhaust made mice crave higher calorie diets. The new study follows human kids who consumed 34% more food high in trans fats if they had constant early exposure to air pollution.

CURWOOD: So was this related to income or race or anything like that?

DYKSTRA: No, the scientists that did the study said they were very careful to make sure it crossed economic lines, racial lines and looked at all income levels.

CURWOOD: So, it turns out that sitting in a car isn't what makes you fat, necessarily; breathing the air that goes by, huh?

DYKSTRA: Breathing the air -- and apparently there's a possible link between inhaling air pollution and later on inhaling Big Macs.

Svante Arrhenius authored one of the first definitive papers on the greenhouse effect. (Photo: Personal Head shot, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: And what do you have from the history vault for us today?

DYKSTRA: The 160th birthday of one of the leading lights of climate scientists, the chemist Svante Arrhenius, a Swede, born on February 18, 1859. He published one of the first definitive papers on what we now call the greenhouse effect. It turned out to be one of the biggest I-told-you-so's in the history of science, back in 1896 when he suggested that coal burning could impact temperatures in Europe.

CURWOOD: Well, he got that one right! So this Swede was a big deal scientist of his times, right?

DYKSTRA: That's right, Arrhenius was also involved in researching the Northern Lights, the aurora borealis, and he won the third ever Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on electrical conductivity. Happy 160, Svante Arrhenius!

CURWOOD: Thank you, Peter! Peter Dykstra's with Environmental Health News, that's EHN dot org, and DailyClimate dot org -- and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these on our website LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- The Salt Lake Tribune | “Trump’s team offers a new vision for Utah’s former Grand Staircase: Nearly 700,000 acres would be open to mining or drilling”

- USC News | “Does air pollution make teens eat fattening foods?”

- Lenntech | “History of the Greenhouse Effect and Global Warming”

[MUSIC: Manhattan Transfer, “The Twelfth” on Vibrate, by John Yano, Telarc]

Neighborhood Burn Squads Fight Fire With Fire

Nevada City residents at work on a controlled burn. (Photo: Nathanael Johnson / Grist)

CURWOOD: In November 2018, in the wake of the devastating Camp Fire, a town called Paradise looked more like Hell. That burned out California community was just another victim of climate change-fueled wildfire. Now, some Californians who live in fire-prone areas are starting to take matters into their own hands, but very carefully. They’re forming “neighborhood burn squads” teams of residents who learn how to safely set fire to the pine litter and scrub bushes known as chaparral close to their homes. Nathanael Johnson wrote for Grist about one of these grassroots efforts, in Nevada City, California. He joins me now from Berkeley. Nate, welcome to Living on Earth!

JOHNSON: Great to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So you grew up in Nevada City. What was that like?

JOHNSON: Nevada City is a beautiful place. It was a great place for me to grow up, as someone who loved the outdoors and liked kayaking down the rivers and climbing on the rocks and that sort of thing. We went backpacking every summer. And we were surrounded by trees, trees were a big part of my childhood. And so were fires. There were a few big fires that really left an imprint on my memories.

CURWOOD: Tell me what it looks like there. People can maybe relate to it in terms of Lake Tahoe, perhaps?

JOHNSON: Yep, it's about halfway between Sacramento and Tahoe. So, you're climbing up into the mountains, but you're not all the way up in the alpine region. So there's a mix of oak hardwoods and Ponderosa pines, and this really red earth, and lots of chaparral growing into the bare spots, which is also a real fire starter.

CURWOOD: So, Nate, you've witnessed one of these neighborhood burns squads in action on a property there in Nevada City, what was that like?

JOHNSON: It was a lot of fun, actually. I went early one morning, it was just after a rain, so things were a little bit damp and cool; the fire wasn't likely to get out of hand because of that. And there's something about fire that just draws people together. It's fascinating. It's warm. And we just watched as the people who had a little more experience with this, set the pine needles on the ground on fire, and felt the warmth coming off of them and watched as it moved along the ground. And they did this very carefully. Fire moves uphill, so they started at the top of the hill and made a little burned strip and then moved a little bit down and made the next burn strip; and just tried to stay out of the smoke and watched as this fire turned this thick layer -- you know, there was about three or four inches of duff on the ground, these leaves and pine needles that you could kick up with the back of your heel. And it would turn the top of that from maybe two inches to just this thin film of ash.

CURWOOD: And how close to houses were these folks doing this burn?

JOHNSON: This was pretty much right up against the house. There was a house about 100 feet away, and it was separated by a rock wall, and we raked clear a little strip next to the wall in hopes of making sure that it didn't jump over and get to the house.

CURWOOD: So who led you in this process? I mean, most people don't know how to do controlled burns, I would guess.

JOHNSON: That's right. This was led by a guy named Dario Davidson, who is a retired forester who's done a lot of controlled burns in his life. Dario is an older gentleman, he's -- white hair and white beard closely cropped. When I got there, he had on his yellow firefighter long-sleeve shirt and really grubby baseball cap and well-worn leather gloves and he was holding this drip can, which is, you know, basically a very low-powered flamethrower, that drips fuel out onto the ground and lights it on fire at the same time.

Dario Davidson is a retired forester who is helping conduct safe controlled burns. (Photo: Nathanael Johnson / Grist)

CURWOOD: Now, what got Dario doing this. I mean, he's out of the forestry business after all.

JOHNSON: So Dario bought about five acres of land nearby where this controlled burn was. And because he was a forester, he knew he had to clear around his house and cut back the underbrush that was growing to protect against fire. And he thought he was doing a great job. But when he started to look at maps of fires, he could see that these big fires, they burned right through. They didn't leave these little gaps of the properties of people who'd done a good job clearing their land. They just burned everything. If you've got enough heat going up, it's just going to set everything on fire. And so he realized that if his preparations were going to count for anything, he had to enlist his neighbors as well. And so he started calling around and got some people together, and figured out a mailing list for the folks in his area, and started organizing, getting people to talk to each other and motivate each other to make their entire community more fire safe.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the physics, really, of where these houses are located and the fire risk that they run.

JOHNSON: So in this area, people move up into these forested communities because they love trees. And a lot of these houses are really nestled in among these dense Ponderosa pines and Douglas firs, which is just a terrible idea when you're in fire country. And so when you have a big fire coming up the hill that's lighting the canopies, that's lighting the tree tops, if you're tucked in among the trees, your house is going to go. Now the fire agencies suggest that you have 100 feet minimum of defensible space that's clear around your house. And if that's the case, you know, you have a fighting chance of saving the house. But it all depends on how hot the fire is. If you have just a massive fire coming up the hill, it's going to throw off enough heat that even 100 feet away it may be hot enough to ignite the house. So that's where these neighborhood solutions really start to matter. If you're reducing the fuels on a neighborhood scale, then there's just less heat overall. And these houses aren't as likely to go up in flames.

CURWOOD: Nate, talk to me about how residents are actually organizing themselves into these burn squads to do the kind of controlled burns that you went and saw.

JOHNSON: This is a, very much a grassroots kind of thing. People are getting together in their living rooms. They're inviting their neighbors over, they're writing letters to people who they don't know but they know their address because they drive by the driveway every day on their way home. And there's some organizations that help with this. So there's something called Firewise Communities, which is a national organization that can help people figure out what to do once they've formed the basics of community organization, what kinds of programs they might want to pursue, and how to get grants to help them chop down the brush and carted out of their properties and that sort of thing.

Because fire moves uphill, the group started at the top of the hill and worked in sections, gradually moving down the hill. (Photo: Nathanael Johnson / Grist)

CURWOOD: So local chapters of this are formed; talk to me about the woman Suzanne you described in your story.

JOHNSON: Suzanne is a member of the Fire Wise Council that I profiled in my story, and I went to this particular one because I was up visiting my mother for Christmas, and she's a neighbor of my mother, this is all very close to home. And Suzanne is just another local landowner who moved to the area knowing that she was moving into a forest, knowing that she'd have to deal with some wildfire risks. And really became acutely aware of this as these big burns started to happen throughout the state, and turned to this local organization that was rising up as a way to prepare -- you know, channel some of that anxiety -- and prepare for what she sees as the inevitable. She told me that for her, it's it's not a matter of if, it's a matter of when there will be a big fire in that area.

CURWOOD: Oh my. So why doesn't she move?

JOHNSON: Well, as she sees it, there's risks all over the country. She lived in a place where there were risks of hurricanes, she lived in another place that was downstream of a big dam that carried a risk for a major flood. So it's kind of hard to get away from risk entirely, especially as the climate changes. Sometimes my wife will ask me, you know, you write about the climate; where should we move to get away from climate risk? And my answer is always, there really isn't any place. Anywhere you're going to be, you're going to have to weigh the risks.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent do any of the Nevada City residents talk about our changing climate as a factor in wildfires?

JOHNSON: They talk a lot about it. Nevada city is, it's one of those classically hippie and redneck type of mixes. So, you have the old timber economy and the old mining economy, and you have this new wave of people who are moving up, who are artists and who are tech workers working remotely. And they mix together sometimes harmoniously, sometimes less so. But certainly, the new wave of people that are, that were drawn up to the area by this sense that it was this artsy, happening place, are believers in climate change. And there's also just this sense that something is different now. You know, we used to have these big fires once every five or 10 years. And now in the last five years, it's seemed like we've had several fires in the county itself every summer, it seems like recently And then you have these massive fires elsewhere in the West that cast smoke across the sky, and really impact the quality of life for major sections of the population. And that certainly leaves you with the sense that the world is burning down or ending, it really feels apocalyptic. So the recent years have felt truly different when it comes to the fire season. And when people are looking around to see what's changed, they cast their eye toward climate change.

CURWOOD: I imagine there's some practical suggestions, or even some practical trainings that these Firewise Councils do; tell me some of those things.

JOHNSON: Well, they suggest that the members of these communities work together to clear the brush from their land, to teach each other how to make their homes more fire safe. You can do things like switching out the wooden shakes on your roof for aluminum roofing or asphalt tiles; you can clear a sort of a meadow around your house, rather than having kind of a dense forest right up to the walls. So there's all these sort of just basic education. And then there's also this motivation to create a plan. So what do you do when a big fire comes? If you have one day to evacuate, how much are you going to pack? What are the things you're going to throw into the car? If you have one hour to evacuate, who are you going to call, what are the things you're going to throw into the car? And these are the kinds of things that, if you have a plan, if you have something written down, it's a lot easier to remember and to do it correctly. So Suzanne showed me her copy of her plan. And it was just really impressive, you know, these things that I wouldn't have thought of, like turning off the electric garage door so that it could be opened by hand, if firefighters needed to get in there and the lines were down.

Firewise associations are popping up all over Nevada County in California (Photo: Nathanael Johnson / Grist)

CURWOOD: So what's the level of concern that folks might carelessly try to do their own controlled burns without the proper experience or knowledge?

JOHNSON: I think there's a lot of concern about that. If people are just setting things on fire, the results are going to be catastrophic. And the reason that this particular controlled burn worked and was so safe and so manageable was that, you know, maybe three or five years back people had already come in and taken out the underbrush. So we're really just talking about this layer of pine needles that was burning. If you go to an overgrown lot somewhere in Nevada County that hasn't been treated and you think "well, I don't want to do all this hard work, cutting back the Manzanita and pulling out the Scotch broom, I'll just set this on fire," you're going to create a major forest fire. So even people like Dario Davidson, who was saying, look, really what we need to do is these repeated, small, slow, controlled burns and reduce the fuels -- even he was saying, I don't really know if I want individual landowners just doing this for themselves. We really need to make sure that for every one of these, there's someone there that has done it before and knows what they're doing and signs off on it.

CURWOOD: Nathanael Johnson is a senior writer for Grist. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Nate.

JOHNSON: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Grist | “Friendly Fire: Can neighborhood burn squads save California from the next big wildfire?”

- Firewise Communities

- New York Times | “Climate Change Is Fueling Wildfires Nationwide, New Report Warns”

[MUSIC: Connie Dover, “An Air For Mary Tipton” on Somebody, by C. Dover, Taylor Park Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth