February 22, 2019

Air Date: February 22, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Wall Street and the Green New Deal

View the page for this story

Much of the criticism of the Green New Deal, a bold plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and create jobs, focuses on its significant costs. But when it comes to financing, the federal government doesn’t have to go it alone, some Wall Street observers point out. Sustainable investing is already a $12 trillion market and growing. Jon Powers is the president of Clean Capital and sits down with Host Bobby Bascomb to explain how investors might be enticed to claim a slice of the Green New Deal pie. (07:56)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how a coal plant that transformed Paradise, Kentucky into a ghost town is now being shut down. Then, they look at a study from NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab, which confirms that recent spikes in atmospheric methane are linked to oil and gas fracking. And in the history calendar, a look back to the hundred-year anniversaries of two of the most-visited National Parks, Grand Canyon and Acadia. (04:38)

Listening to Forests Can Aid Conservation

View the page for this story

A technique called bioacoustic monitoring is helping scientists get a better picture of the biodiversity of forests. Animals like birds, primates and insects make sounds that can be picked up by recording devices and tell scientists a lot about the health of a forest. Rhett Butler, the CEO and founder of the environmental news agency Mongabay, talked with host Bobby Bascomb about the possibilities of using bioacoustics data for conservation in places like the Amazon and the Bornean rainforest. (09:47)

California Tree Deaths Could Hurt Forests on the East Coast

View the page for this story

New research shows that tree deaths in California can hinder plant growth all the way across the continent in Eastern North America. Abigail Swann from the University of Washington, explains to Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood how tree deaths cause changes in atmospheric moisture and impact local climates thousands of miles away. (08:13)

Confronting Climate Change Through Sound

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

The seemingly constant onslaught of grim statistics and graphs about climate change may cause some people to shut down, unwilling or unable to process one of the most serious environmental issues of our time. To draw people back into a conversation about our changing climate, researchers at the University of Virginia are using something called eco-acoustics – sounds that illustrate the relationship between humans and their environment. Reporter Sandy Hausman has the story. (04:09)

Saltwater Beavers Bring Life Back to Estuaries

View the page for this story

Until recently, biologists assumed that beavers occupied freshwater ecosystems only. But scientists are now studying beavers living in brackish water and how they help restore degraded estuaries and provide crucial habitat for salmon, waterfowl, and many other species. Journalist Ben Goldfarb speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb. (09:43)

BirdNote®: Anna’s Hummingbirds Winter in the North

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Most hummingbirds in the northern hemisphere head south during the winter, seeking out warmer climates near the equator. Anna's Hummingbirds, however, stick around as far north as British Columbia, using a nightly hibernation technique to keep themselves warm throughout the chilly winter nights. BirdNote's Mary McCann has the story. (02:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Rhett Butler, Ben Goldfarb, Jon Powers, Abigail Swann

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Sandy Hausman, Mary McCann

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

From the Amazon to Papua New Guinea, listening to tropical forests can tell us a lot about biodiversity.

BUTLER: Bioacoustics is really interesting because you can capture a much broader range than you would get with camera traps. So this gives us a more nuanced look at what's actually happening under the tree cover -- what species are present, and even the health of an ecosystem.

BASCOMB: Using sounds of the forest to catch poachers and illegal loggers. Also, an overlooked habitat for the busy beaver.

GOLDFARB: They're not only using saltwater to disperse, they're actually living full-time in these intertidal estuaries, and are actually doing all kinds of really interesting engineering and architecture, and are playing this really important ecological role in saltwater ecosystems.

BASCOMB: How coastal beaver dams can help baby salmon thrive.

That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Wall Street and the Green New Deal

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Senator Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, right, announcing their Green New Deal resolution on February 7, 2019. (Photo: Senate Democrats, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

The Green New Deal resolution was recently introduced to Congress. It aims to address the climate crisis, in part, by committing to 100% zero carbon energy in the next ten years. It’s also a plan to alleviate poverty and create millions of new green jobs. One of the biggest criticisms of the ambitious plan is the cost. Even if Congress could agree in principle, critics say the government can’t afford to fund the proposed programs. However, they may be overlooking an obvious source of revenue: Wall Street. Sustainable investing is already a 12 trillion dollar market and growing. Jon Powers is the president of Clean Capital and served as federal Chief Sustainability Officer under President Obama. He joins me now to explain how investors might get behind portions of the Green New Deal. Jon, welcome to Living on Earth!

POWERS: Thanks so much for having me.

BASCOMB: So how willing are banks and private equity firms when it comes to investing in renewable energy? And why is green energy or renewable energy, why is that a good investment for these institutions?

POWERS: Yeah. So the reality is they're looking for capital to put out that is going to have solid return. So let's look at a solar project and look at how it's financed, right. So when you have a big corporation, a lot of corporates, whether be Walmart, Apple, eBay, are going 100% renewable energy through these contracting measures called power purchase agreements, and it's a growing space. You've got unbelievable opportunity right now where corporate leaders are filling the void of Washington by going ahead and committing to this power. So they put in place a 20 year contract to buy electricity off of, for instance, solar panels that are on the roof of the warehouse. So that's a 20 year cash flow of an investment for a proven technology. It’s a pretty safe bet for the investors and you know, they can put their money to work and see returns pile up year after year.

BASCOMB: So part of the strategy of the Green New Deal, of course, is to create jobs in the course of installing all that renewable energy, you know, solar panel installers, for instance. Is job creation something that investors consider it all or is this purely about the bottom line for them?

POWERS: You know, it's obviously an important part; I think, depending on the investor, it's about the bottom line. Some investors have different metrics like ESG, Environmental Sustainability and Governance goals, and that can be driven by job growth or things like pollinators at solar panels, at solar arrays. So there's different ways to measure those ESG goals. The interesting things about the jobs space, and I think it's important to step back and look and where we are with clean energy. In 2008, there was barely any solar out there, for instance, and wind was just beginning to grow. Things really began to take off because you had policy certainty begin to come into place and you had alignment of efficiencies across the market. So what does that mean? Under President Bush, they put in place the Energy Security Act, which gave tax credits of things like wind and solar. And then when the market sort of crashed in 2008, a lot of government capital came into what was known as shovel-ready projects. And as a result, clean energy really started to get traction. Technologies like solar began to become proven. And then specific jobs like solar installers or O&M technicians began to grow. And more and more folks entered that space. Then you have what's known as sort of efficiency in the market. Right? People knew how to install these things. They knew how to measure them and manage them. And as that efficiency grew, more and more capital moved into that market, continuing to drive down the cost of doing the deal and making, for instance, doing things like solar and wind that much more affordable.

BASCOMB: Well, critics of the Green New Deal say that the proposals are just too expensive and the government can't foot the bill for them. What is the potential, do you think for Wall Street and private investors to cover these costs. I mean how far could this investment money actually get us towards these goals?

Jon Powers is the president of CleanCapital and served as Federal Chief Sustainability Officer under President Barack Obama. (Photo: Jon Powers, CleanCapitalLLC)

POWERS: It's a weak argument for the critics, because the reality is the government capital that will be used is to hopefully provide certainty to allow the markets to flow, right. So if you looked at, again, flashing back to clean energy the last 10 years, as certainty began to come into place, people understand these technologies work. People talked about putting solar power in New Jersey in 2008. People would say, Hey, does the sun even shine enough in New Jersey to get these projects, do these solar panels work? Now, flash forward 10 years, there's solar all across New Jersey, people know what contracts like power purchase agreements are, they know what the solar renewable energy credits work, and how the market works. And capital’s flowing that you don't need the government money to do it. You just need that policy certainty.

BASCOMB: We've always heard that the one thing that investors really need most when it comes to making decisions about where to put their money is stability, to know what the future of the market is going to look like. How true is that and why?

POWERS: Yeah, that's, I think that's very important and critical. So when you're looking at investments -- so think about Nevada last year, there was an effort in Nevada to pull what were known as net metering policies off the table. So why does that matter? So if you're making clean energy or solar, you can sell the power back to the grid for a time that it's not being used. WelI, if you did a deal that had that policy in place, once that's removed it can cut the legs out of the transaction, because you actually have to, what's known as sort of model that risk into the deal. So every time those policies swing back and forth it's a challenge to get capital to commit. And the problem with that is not -- there's, there will be capital out there that will take those riskier bets. But the problem is that's more expensive money. The more certainty you have, the better cost of capital you can have. So you can have pension funds or long term life insurance investors for instance that have lower cost of capital commit to those longer investments, making the deals that much more efficient; it’d make the cost of electricity, for instance coming off that deal cheaper so we can see more and more growth of the market. Again, the certainty’s key to get that cheaper capital. When there's not certainty, the money will just be more expensive.

BASCOMB: Right. Well, I've read that sustainable investing is already a $12 trillion market in the US. What do you see as the future for that type of investment? Where's it going from here do you suppose?

POWERS: So, sustainable investing covers a broad spectrum. And it can go from investing in clean energy projects, it can count in things like green bonds, water programs, supply chain investing. But you know, that is a relatively, still a new area; corporate America is wrapping their heads around sustainability, for instance, in their practices. And as the data becomes clearer, the metrics become clearer, people will understand better what they're investing in, that will only continue to grow.

BASCOMB: Now you are president of a company called Clean Capital. Investing in clean energy is your bread and butter. It's right there in the name. But if we look at Wall Street investors more generally, how willing are they to also put their money towards renewable energy projects? Do you think that you’re representative of the whole?

POWERS: There is a phenomenal demand right now to move into clean energy. You'll see it, for instance, in the ideas around fossil fuel divesting that's happening with pension funds and college endowments. Now we need to take those initiatives to the next step, which is investing. For us, it's not just about investing in clean energy, though. It's about making a solid investment as an asset class. Clean energy is that asset class. It's matured enough that people understand that now, but it still takes continuous education, like in any asset age; not student loans, not home mortgages. This is still a growing space.

BASCOMB: Jon Powers is host of the podcast Experts Only, President of Clean Capital and former federal Chief Sustainability Officer under President Obama. Jon, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

POWERS: Yeah! Thanks so much for having me. And again, thanks so much for focusing on this issue.

Related link:

Bloomberg Businessweek | “Wall Street is More Than Willing to Fund the Green New Deal”

[MUSIC: Nino Rota/conducted by Franco Ferrarra, “La bella malinconica” on Arrivederci Italy, by Nino Rota, Sony Music]

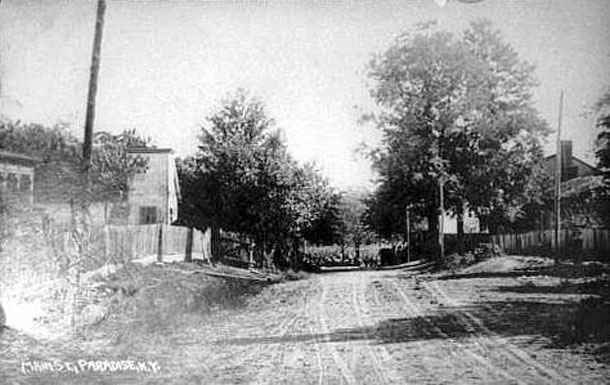

Beyond the Headlines

Main Street, Paradise, Kentucky. Paradise is a ghost town, the only structure left standing is a coal plant built in 1959 by the Tennessee Valley Authority. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey, there, Peter. What do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. You know, there's a song been running through my head the past few days. It’s an old classic by John Prine about a ghost town called Paradise in Western Kentucky. The town was bought out by the Tennessee Valley Authority due to pollution from a huge coal plant and the fact that there were open coal mines all throughout the area.

BASCOMB: And what's got you thinking about that song this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's a piece in Inside Climate News reporting that the TVA has proposed that the antiquated Paradise coal plant, along with another coal plant in Bull Run, Tennessee, be shut down over the next few years. All of this in spite the fact that President Trump has been lobbying to preserve these coal plants, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky has also been lobbying to keep the plants open.

BASCOMB: I’ve read that one of the coal mines that supplies coal to the plant in Paradise is actually owned by Robert Murray. He’s CEO of Murray Energy and also happens to be a big donor to President Trump's campaign.

DYKSTRA: And one of the biggest, most outspoken boosters of the coal industry and deniers of the effects of climate change.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. All right. And what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, Houston, we have a fracking problem. There's a new NASA study from the Jet Propulsion Labs that may solve a climate mystery, confirming that recent spikes in the greenhouse gas methane are linked to oil and gas fracking.

BASCOMB: What's the source of that exactly?

DYKSTRA: Uh, well, the methane discharges are an inherent part of fracking. Bear in mind that methane is 86 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. The JPL study said that the rise in atmospheric methane is largely a result of fracking operations picking up around the world.

BASCOMB: So climate advocates might say there's some good news this week. Uh, coal just can't compete, but it's being replaced to some degree by natural gas, which might be just as bad or worse.

DYKSTRA: Or worse. And that's a distinct possibility.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Hundredth anniversary of note, actually two of them. February 25, 1919, Grand Canyon National Park was created. The Grand Canyon had actually been a national monument. Back in 1906, Theodore Roosevelt started using the Antiquities Act to preserve wild areas of the west. Grand Canyon got that protection in 1908, became a park in 1919, and so did another park you may not have heard of: the Lafayette National Park.

BASCOMB: I haven't heard of that one.

DYKSTRA: Well, you may have heard of it in its new name. 10 years later, in 1929, the Lafayette National Park was renamed Acadia National Park, the crown jewel of the park system on the East Coast. Acadia, and of course, the Grand Canyon are two of the most heavily visited parks in the whole system.

The Grand Canyon was named as a National Park in 1919. Previously, it had been an official national monument since 1908. (Photo: Paul Fundenburg, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: I've been lucky enough to visit both and they're beautiful, but not the oldest, of course. Yellowstone has that distinction. It's the oldest park in the country and the second oldest in the world.

DYKSTRA: It is, and the park system in the US is a gift that keeps on giving. We may be looking at the follow up to the land-based park system. The series of marine reserves that the US and other nations have created around the world could be the national parks of the 21st century.

BASCOMB: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter. We'll talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: There's more on these stories on our website LOE.org and by the way, here's a snippet of that John Prine song about Paradise, Kentucky.

[MUSIC: John Prine, “Paradise” on John Prine, Atlantic Records]

Related links:

- The song “Paradise” by John Prine

- Inside Climate News | "TVA Votes to Close 2 Coal Plants, Despite Political Pressure From Trump and Kentucky GOP"

- EcoWatch | “New NASA Study Solves Climate Mystery, Confirms Methane Spike Tied to Oil and Gas”

- History.com | “Theodore Roosevelt Makes Grand Canyon a National Monument”

- Friends of Acadia | “Acadia Name Day: January 19”

BASCOMB: Coming up – How dead trees in California can impact plant grown on the East Coast. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nino Rota/conducted by Franco Ferrarra, “La bella malinconica” on Arrivederci Italy, by Nino Rota, Sony Music]

Listening to Forests Can Aid Conservation

Zuzana Burivalova and researchers gather around programming the recorders used to monitor sound. (Photo: Justine Haushneer, The Nature Conservancy)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

A tropical rainforest looks a bit like broccoli from above. Tall canopy trees spread their branches ever higher and wider in search of the sun, creating a bumpy uneven carpet of green. Satellite images of a rainforest might show a lush tree canopy, but they reveal very little about the biodiversity of the ecosystem. So, to see if a forest is intact and healthy, perhaps we should be listening instead of looking. Using a technique called bioacoustics, researchers are exploring ways to monitor forest health by listening to the animals living there. Rhett Butler is editor in chief of the environmental news agency Mongabay and co-authored a recent paper about bio-acoustics in the journal Science. Rhett, welcome to Living on Earth.

BUTLER: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So you can listen to an ecosystem. Why is that preferable over something like remote sensing, using satellites to look at an ecosystem, as opposed to listen to it, or even on the ground surveys?

BUTLER: Well, remote sensing is really important. It gives us a very big picture look at what's happening. But if we want to actually see what's happening under the tree canopy, then using something like a camera trap can be very useful. But bioacoustics is really interesting, because you can capture a much broader range than you get with camera traps. So this gives us a more nuanced look at what's actually happening under the tree cover -- what species are present, and even the health of an ecosystem.

BASCOMB: So how many of these study sites do you have in place, and where are they?

BUTLER: My coauthor and the lead author on this paper that just came out in Science, Zuzana Burivalova, and our other coauthor Eddie Game, they have study sites in Borneo and Papua New Guinea. That said, there are a lot of other researchers who are using bioacoustics all around the world. So we're talking a very large number of sites where data is being collected right now.

BASCOMB: So how does this work in a place like the Bornean rainforest? I mean, tropical forests are, by definition, hot wet places. That's not the best environment to have sophisticated recording devices lying around.

Bioacoustics allows researchers to gather data over time and determine what are the best conservation methods in protected areas. (Photo: Ben Von Wong)

BUTLER: Yeah so there a couple of ways to go about this. So the most common way is to use these waterproof boxes that have a recording device in them, and these are very standard, off the shelf stuff. It's really not that expensive anymore. And you just mount these in the trees. So you can set them to record at certain times of the day, and then just come back and collect the data every, you know, few weeks, months. So that's, that's one mechanism. A more exciting mechanism, from my viewpoint, is setting up something that's linked to a network. And so there's this project called Rainforest Connection, which uses modified cell phones, and it mounts these high, maybe 100 feet in the canopy, and it has a solar array around the cell phone to power it, and they just sit up there and collect data and then send it in real time, because there's a network link, and then it, you can listen to it, you know, in California.

BASCOMB: If you had an interconnected network like that, I imagine that opens up the possibility, too, of more enforcement. So if you hear a chainsaw or gunshot or something in the forest, you could send out law enforcement to go check it out and address the issue.

BUTLER: Exactly. That's, that's one of the most exciting things about this space, is the possibility of doing real time law enforcement and other forms of interdiction. So if you hear a gunshot, if you hear a car engine, if you hear voices, you know, you can get a real time alert and then take action as something's happening. And so with satellite data, you have this delay. With most systems, you're looking at, at best a week delay in terms of when you start to see something on a satellite versus when you can actually take action. So a bioacoustic system that's networked, you could actually take action before deforestation occurs. So once you first start to hear the first chainsaws you could send someone in before it actually becomes deforestation.

BASCOMB: Well, you've sent us some examples of what a healthy forest sounds like versus one that's been selectively logged. Let's take a listen before and after. I believe this is from Borneo, right?

BUTLER: Yeah. So this would be from East Kalimantan which is Indonesian Borneo. And this would have been recorded by Zuzana Burivalova.

BASCOMB: Great. Well, let's take a listen to the before.

[FOREST SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: What are we hearing there, Rhett?

BUTLER: Well, you're hearing a very busy forest. So all these different frequencies are being filled by different animals. And so you can hear kind of, the raucous call of the hornbill; you have a lot of other birds; the background noise is a lot of insects; there's a gibbon calling, which tends to be on the low end of the spectrum. And so, Bernie Krause, who's kind of a legend in this, in the soundscape ecology field, and I think even coined the name, you know, he's described this as there's different niches and you'll have different organisms that fill different parts of that. I think in this example, you can really hear kind of the full range of animals and it showcases that this is a biodiverse, healthy system.

BASCOMB: Well, let's hear the same area after selective logging has taken place. I believe it's about two weeks after the forest was logged. Let's have a listen to that.

[FOREST SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Wow. That's pretty quiet by comparison.

BUTLER: Yeah, you've lost the birds, you've lost the mammals. Really you just have the background insects. I mean, it's just a night and day difference.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it really is. Well, what got you interested in how bioacoustics can be used to monitor forest health?

BUTLER: So this project emerged out of a series we did a couple years ago looking at what works and what doesn't work in conservation. And that series specifically looked at what does the science tell us. And we hired Zuzana Burivalova, who again is the lead author on this paper, to be the lead scientist on the project. And what we found is that the science has not done really a great job at evaluating effectiveness of different conservation interventions. So it's hard to say what really works and what doesn't work based on the science. So you have to kind of go into the gray zone and anecdotal evidence. And so that got us thinking about, well, are there ways that we could kind of address this issue, and Zuzana works on bioacoustics. And digging into it a bit more, it seemed like a great way to scale up monitoring of biodiversity, which could then be used to inform evaluations on what's working, what's not working, because you could compare different conservation interventions and say, okay, well, in this forest, you have this level of biodiversity, where in this one, it's a lower level or something like that. So the other great thing about this is that you can create historical baselines. And then as technology and species identification improves over time, you can go back and run algorithms against that original data and see what's been lost and how things have changed.

Acoustic recorders can detect sound from hundreds of meters away, helping researchers monitor wide areas in the rainforest. (Photo: Justine Hausheer, The Nature Conservancy)

BASCOMB: Or, I mean, there's sustainable palm oil growers. But how sustainable is it really, if you're not protecting the biodiversity? I guess you could use it in that way.

BUTLER: Yeah. And so we see a big opportunity around these zero deforestation commitments that a lot of palm oil companies have been signing. And so the idea of one of these commandments is, a palm oil company may have an area of forest within their concession that they agree not to chop down as part of this commitment. But what bioacoustics could do is it can tell us the quality of that forest area. And so one of the issues in oil palm plantations is because you have all this fruit on the ground, in Asia, you tend to have explosions in the population of pigs. So then the pigs are, you know, feeding on this oil palm fruit and then they kind of run amuck and take over the forest reserve. And so you may end up with a highly degraded forest reserve, and even though it's protected, it's no longer a high-quality forest. You know, in other cases you may have hunting within these concessions. So you may see, okay, well, there's trees there, but there's no actual wildlife on the ground. So that's one aspect, you can use it for monitoring. But companies could also use it for looking for risk to their commitments, so they could hear whether you're, the area you've committed to protecting is being cut down, or threatened by poachers or things like that. So a company could actually, you know, send in someone to take a look at what's happening in that forest. And where this is particularly relevant is in Southeast Asia, so Sumatra and Borneo, where in the dry season, you have a high risk of fire. And so if you have forest reserves that are supposed to be protected and are within these concessions, and all of a sudden you're hearing gunshots or voices or, or chainsaws, that tells you that there are people present, which is a risk for fire. Because all it really takes is one cigarette in a dried out peat area to trigger a fire that could then get a company in a lot of trouble.

BASCOMB: What do you see as the future of using this technology, are you looking to scale up and have it in other parts of the world?

BUTLER: What I would love to see is all this data being collected in a central repository that's open to scientists who could then run algorithms against the data to look for patterns. So it could be anything from species distribution to degradation to the impacts of climate change. This could become really powerful with networked bioacoustic devices, where you have large amounts of data getting just fed into the central repository. So I think if you took that, combined it with camera traps, especially networked camera traps, and then satellite data, you would get a really, really a much better picture of what's happening with biodiversity, wildlife populations and forests in these places.

BASCOMB: Rhett Butler is the founder and CEO of the environmental news agency Mongabay. Right. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me.

BUTLER: Thank you. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Mongabay | "Eavesdrop on Forest Sounds to Effectively Monitor Biodiversity"

- Read the paper: “Forest Soundscapes Monitor Conservation Efforts Inexpensively, Effectively”

- About Zuzana Burivalova

- About Rhett Butler

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma/Rosa Passos/Paquito D’Rivera/et al, “Aquarela Do Brasil” on Obrigado Brazil Live In Concert, by Ary Barroso/arr.J. Callandrelli]

California Tree Deaths Could Hurt Forests on the East Coast

Drought-killed trees killed in California, pictured in 2016. (Photo: Nathan Stephenson, USGS)

BASCOMB: Deforestation and tree loss are not isolated to the tropics, of course. Since 2010 roughly 130 million trees have died in California alone. Instead of chainsaws and agriculture, bark beetles and drought are largely to blame but the result is the same. And according to new forest modeling research those tree deaths in California can have big impacts on other parts of the country, as far away as the East Coast. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood spoke with University of Washington Professor Abigail Swann about her recent study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

SWANN: We looked at a bunch of regions in the US. And we've looked at what would happen if forests were removed in those regions. And these are regions that the National Science Foundation has identified as sort of eco-regions. And we took each of these ones that had a lot of forest cover in them, and we said, What would happen if those forests were gone? So it turns out that plants are able to influence the atmosphere around them, so they can influence the local climate that's experienced nearby, but that the atmosphere, because it is circulating around, is moving, those local changes, they can get communicated to other places. And so changes in plants in one location can actually have impacts on the climate somewhere else. And that can also impact the plants somewhere else. Because plants are influenced by the climate that they're experiencing. We found that the location of the forests really matter. So in general, losing tree cover in the West, particularly in areas like California had bigger negative impacts, meaning it, it led to less plant growth across the continental US. But there were some places where removing trees led to more plant growth across the US in general.

CURWOOD: So what makes a difference?

SWANN: It's really the location of where those plants are, and how they're able to influence the atmosphere and what changes in climate that leads to, that plants care about. So what we found is that in general, plants grew more when the summers were a little bit cooler and a little bit wetter. And so if forest loss led to hotter summers, or drier summers, then we saw less benefit for plants in general.

CURWOOD: How exactly does that work? I imagine it's related to evaporation, among other things.

SWANN: Right well, the local surface temperatures care a lot about how much water gets evaporated. So in general, when water is able to evaporate off the surface, you'll get less change in temperature. So your skin, when water evaporates off your skin, when you sweat, it helps keep you cool. If there isn't as much water available, the surface is likely to get warmer. And so that influences the local temperatures. The reason the atmosphere can sort of propagate that signal elsewhere is because it's essentially, you know, the atmosphere is a big fluid. And so waves and other things propagate in the atmosphere. And that signal can be transmitted somewhere else where it then has some impact on climate. The really classic example of this would be like an El Nino. So we're all pretty comfortable with the idea that this thing called El Nino influences climate in places in North America. But it's actually a big sloshing around of temperature in the tropical Pacific Ocean. And so that big sort of oscillation in temperature in the tropics influences the atmosphere, kind of like dropping a rock in the pond. And that signal propagates to North America where it then influences temperature or rainfall over different parts of the US.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is, if you lose a bunch of trees in California, it's like dropping a rock into this fluid we call the atmosphere, and the ripple will come out east and it'll have effect on trees there?

SWANN: That's the idea. And our hypothesis, based on these simulations, is that that impact is generally bad for plants across the eastern US.

CURWOOD: And remind us of what's driving the tree loss to begin with in the West.

SWANN: Right. So the tree last that we are seeing across California has really been driven by an extreme drought over the last few years. So it's been very dry. And I think the Forest Service has estimated about 120 million trees have died due to these really harsh conditions of low water and high temperature. And so there, there has been pretty significant tree death occurring across California just in the last couple of years. But more extensively across the western US in the last decades, we've seen a lot of trees that have died due to beetle outbreaks and other pest problems.

Wildfires in the forests of the American West are becoming more frequent and, in California, they took a devastating toll on lives and property in 2018. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory)

CURWOOD: A couple of decades ago, people looking at how much carbon was going into the atmosphere from North America were doing a happy dance about all the trees that had come back in the East that had been cut down, during the farming in the 1800s. And now this area, especially Adirondacks, is afforested, you guys would say, and that this was sucking a lot more carbon out of the atmosphere. What you're telling me is that, well, wait a second, those trees may not be in such a great position now to remove carbon given what's happening out West.

SWANN: Well, that's possible, right? And this is one of the big uncertainties of how much carbon the whole land system will be able to store going forward is, you know, we there has been an uptake of carbon by those forests, as they regrew. But I think it's very uncertain what that will look like, as we go into the future -- either in North America, or really anywhere else on the globe. There's things about changing climate that will help plants grow better, like increasing temperatures in places that were colder; higher levels of carbon dioxide help plants grow a little bit more. But if they become more water stressed or if it leads to more plant death, that could be really bad. And this is a huge open question in our scientific field that we really don't know the answer to yet.

CURWOOD: So Abby, you study atmospheric science and biology. Sometimes you scientists say that our present time, or up until recently, anyway, we were in a fairly stable what you call an interglacial period, that things were staying pretty much the same. To what extent does your research suggest that well, things really aren't so much the same anymore?

SWANN: Right? Well, I'd say climate change in general, is pushing us very strongly out of that stable environment that we've been in in the past. And as you mentioned, climate change can lead to more stress on trees, that can lead to more tree loss. And we think that in a specific example of our own research, that this would have these larger scale impacts. In general, I think if we think about land systems and plants and how they grow, there's a lot of unknowns about what tipping points might exist. If you think about a system like the Amazon forest, and is it vulnerable to change? What will that system look like in the future under a much hotter climate? We have no examples on Earth right now to compare that to. There aren't places that are hotter than the Amazon but also wet, so we have no place to look to see what that might be like. And so there's a lot of work to do from a scientific standpoint, to try to understand that. But also, I think it's important to say that we don't understand yet, but the potential is scary.

CURWOOD: A number of years ago, the Met Office, that is the UK weather and climate modeling group, said that by the year 2050, the Amazon really could just be a grassland. What do you make of that research? And given your research, what might that tell us? Or what might that warn us?

Forest loss in California could hinder the growth of trees and other plants on the East Coast. Here, a Vermont forest in the midst of its colorful autumn transformation. (Photo: Brad Fickeisen on Unsplash)

SWANN: Right, so there's been a lot of work since the original findings came out. And I think that we understand a lot more about what some of the limitations were of those original studies. But the sort of premise still exists that the Amazon will be experiencing a very unseen climate – or, unseen in any sort of human timescales. Maybe if we go back to the time of dinosaurs, there were temperatures that were that high, but that this is a really new or novel climate that the Amazon will be experiencing. And there's a real question as to what that forest will look like. I think there's less of a thought that it would collapse completely into a grassland, but still a lot of questions of if it will be able to maintain as many trees, or as high of a biomass, or as high of a biodiversity as it does now.

BASCOMB: Abigail Swann is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Atmospheric Sciences and Biology at the University of Washington in Seattle. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Read the journal article published in Environmental Research Letters

- About Abigail Swann’s Ecoclimate Lab at the University of Washington

[MUSIC: Tracy Chapman, “New Beginning” on New Beginning, Elektra Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – listening to the impacts of climate change.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ikebe Shakedown, “Out Of the Shadows” on The Way Home, by Alter/Bourla/Chiarito/Schmidt, Colemine Records]

Confronting Climate Change Through Sound

As glaciers shift and melt, many unsuspected sounds can emerge from the ice. (Photo: Unsplash, Vince Gx)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

When we see statistics and graphs about climate change, many of us may start to shut down, unwilling or unable to process one of the most serious environmental issues of our time. To draw people back into a conversation about our changing climate, researchers at the University of Virginia are using something called eco-acoustics – sounds that illustrate the relationship between humans and their environment. Reporter Sandy Hausman has the story.

HAUSMAN: Willis Jenkins teaches religious studies, but lately he’s been called to the coast, to record the sounds of sea level rise and oyster reefs.

JENKINS: When you hear the reef recording you’re going to hear a snapping or cracking sound, and that is actually pistol shrimp, and then you can also hear kind of micro-currents of water moving in and around the reef, and there may be a few low fish calls.”

HAUSMAN: People who hear that recording are drawn into dialogue.

JENKINS: The sound element is so captivating that people ask lots of questions about it, and then they begin to ask questions about organisms and data change over decades, in conversations that typically go longer than if I were to just tell you about the health of these wetlands.

HAUSMAN: His colleague in UVA’s music department agrees. Matthew Burtner is now working from a cabin near Anchorage, where he’s recording glaciers as they melt slowly --- or suddenly fall into the sea.

BURTNER: It’s an amazing symphony of sounds actually. There are incredibly low, booming sounds. They sound like jet engines up close as these large pieces of ice calve and fall, and then there are most delicate tinkling, trickling sounds that you’ve ever heard – these little tiny patterns of water moving across the ice as the ice melts and creates little tiny melodies, little tiny rhythms, and the whole surface of the glacier is just alive with sound.

HAUSMAN: After recording the sounds of the arctic, he translates climate data into notes and combines them to create compositions that tell the story of global warming. Hearing it, he says, is fundamentally different from reading or talking about climate change.

BURTNER: A lot happens when we shift our focus from looking at the world and moving in the world to just listening to the world. It’s a more contemplative way of being. If we could understand the glaciers as a complex symphony of sound the way we listen to Beethoven, that could do a lot for our relationship to the natural world.

HAUSMAN: The work itself is challenging. It was 65 degrees in Charlottesville when I reached Burtner in Alaska’s Chugach Mountains. There, he said, conditions were very different.

BURTNER: Today it’s three degrees and it’s snowing outside. You know, to do anything you have to shovel out and then you’re constantly trying to keep the equipment warm, because the equipment is not designed to function in sub-zero temperatures.

HAUSMAN: But he loves being outside in any weather, and recording off the Eastern Shore is a pleasure. He and Jenkins can now assess the health of an oyster reef through sound and monitor the size of crustaceans by listening to what they call crab flutes – sounds heard as the wind blows over holes in the sand.

BURTNER: We hoped to be able to record the crab, but the crab made almost no sound, and we couldn’t hear it, but we could hear the wind whistling over the top of the crab glute – this wind instrument that the crab has made.

HAUSMAN: You can hear Burtner’s work on his newly released album, Glacier Music on Revallo Records, featuring what will surely be a hit song entitled the “Syntax of Snow”.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Hausman.

BASCOMB: Sandy Hausman’s story comes to us courtesy of WVTF in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Related links:

- Read the original story from WVTF

- More on Pistol Shrimp

[MUSIC: Snorre Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records Compilation Vol. 25, by Snorre Kirk, Sundance Music/Stunt Records]

Saltwater Beavers Bring Life Back to Estuaries

Because they build dams that shape the very environments in which they live, beavers are a classic example of a “keystone species”. (Photo: Becky Matsubara, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: The eager beaver is an extremely effective engineer of its environment. Beaver dams hold back water that can be a nuisance to homeowners, but they create a complex system of ponds and wetlands that are a haven for numerous plant and animal species.

[SFX WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: On a recent winter morning I went to look for the tell tale signs of the iron toothed rodents at a pond near my home in New Hampshire. I enlisted the help of my 4 year old daughter, Sage, to find, as she calls them, beaver trees.

SAGE: 1,2,3,4,5 a beaver tree

A thin layer of ice blankets the network of ponds, streams, and wetlands in the frigid woods.

SAGE: I found a beaver tree!

BASCOMB: How do you know that’s a beaver tree?

SAGE: Because it chewed all the way down. Ok, let’s keep going to see more.

David Bailey, a biologist with the Tulalip Tribes, stands next to a beaver dam exposed at low tide on the Snohomish River in Washington State. (Photo: Ben Goldfarb)

BASCOMB: Well, we found our “beaver trees” right where you might expect: near a freshwater pond. But scientists recently discovered that beavers are also happy to live in the brackish mix of fresh and salt water in coastal areas. And just as they help restore freshwater ecosystems, beavers could also hold the key to restoring damaged coastal wetlands. Journalist Ben Goldfarb wrote about saltwater beavers for Hakai Magazine, and he joins me now. Ben, welcome back to Living on Earth!

GOLDFARB: Thanks for having me again.

BASCOMB: So first, Ben, how surprised were you to find out that there are saltwater beavers? I mean, you're a self-described beaver believer. You wear beaver t-shirts, you wrote a book about beavers, I mean, you know a thing or two about beavers. How surprising was this?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it was definitely surprising. I think that I and, you know, and all beaver biologists knew that beavers occasionally would swim into saltwater, you know, they dispersed from the mainland to islands in some places. Sometimes they'll go out to the mouth of the river, hang a right up the coastline and travel up aways looking for the next river mouth to go up into. But I think it's just really within the last several years, thanks in large part to this guy, Greg Hood, a scientist who works in the Skagit river in Washington, that we've begun to understand that they're not only using saltwater to disperse. They're actually living full-time in these intertidal estuaries and are actually doing all kinds of really interesting engineering and architecture and are playing this really important ecological role in saltwater ecosystems.

BASCOMB: You actually went to visit one of those beaver lodges on this Snohomish river in Puget Sound. Can you describe that? What was it like there?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it's a really amazing place. So it's basically this kind of vast intertidal estuary and the beavers are building in these kinds of tidal channels. So there are basically, it's kind of this huge salt marsh that's scored with these little freshwater channels that fresh water comes down in. But then when the tide comes up twice a day, those fresh water channels are completely submerged, they're inundated. So it's this really dynamic ecosystem with the tides are just going in and out all the time. And beavers are actually building in there. So they'll build these dams that when the tide comes up, the dams are actually completely submerged under water, you could kayak over the top of one of these dams and have no idea that they were beavers building there. And then when the tide goes out again those dams suddenly reemerge, essentially, and now they're holding back these pools of water in these intertidal channels, so it's almost like the beavers are anticipating these tidal fluctuations and are accounting for them in their construction, and in this really sophisticated way.

The sediment-rich waters of the Elwha River flow out into Washington State’s Strait of Juan de Fuca. The removal of two dams on the Elwha River from 2011 to 2014 restored sediment flow in this important salmon-bearing river. (Photo: John Felis, USGS, Public domain)

BASCOMB: Wow, that is sophisticated. I mean, that's Army Corps of Engineers-level engineering, I think.

GOLDFARB: Totally, except better for the environment than the Army Corps, you might argue [LAUGHS].

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Yeah. So you got there and you found this extraordinary feat of engineering, really, by these beavers. And how do their dams in these intertidal areas affect the ecosystem around them? What kind of habitat are they creating?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, that's a great question. So most of what we know about how important these habitats are comes from Greg Hood, who did a lot of intertidal beaver research on the Skagit River, which is another river in Washington where beavers sort of occupy these intertidal areas. And basically what Greg found is that these are enormously important, these beaver construction sites, are hugely important for juvenile salmon, especially. You know when the tide goes out, those fish would get flushed out into these estuaries where they're really at risk of being preyed upon by larger fish, by birds. That's a pretty challenging habitat to be a little finger-length salmon in. But at low tide because beavers are holding back these deep pools of water they're creating these fantastic refuges essentially for juvenile salmon, that are deep enough that birds like great blue herons can't really get in there to prey on the juvenile salmon. So it turns out, Greg discovered, that baby salmon were three times more abundant in these beaver pools than in other habitat. So clearly they're just creating these fantastic salmon refuges, which is something that we knew that beavers did in fresh water. But we didn't realize until Greg's research a few years ago that they were also playing this same role of creating these salmon refuges in the estuaries as well.

BASCOMB: Wow. So, they really serve a critical function. I mean, everybody likes salmon, right? The bears, the whales, people. Everybody likes salmon, and they're in sharp decline; I mean, could beavers be something of a game changer for salmon habitat, for helping the salmon rebound?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, and I think that again, in freshwater streams, you know, beavers are already being considered this crucial keystone species for salmon recovery. There are so many beaver restoration efforts here in the Pacific Northwest where I live aimed at getting beavers back in these streams and basically creating salmon habitat. There are so many scientific studies that have been published basically showing that beavers dramatically help the survival of juvenile salmon. So that sort of pro-beaver work is already happening in much of the Northwest. You know, a lot of it's catalyzed -- we, you know we saw this past year just how badly the Southern Resident killer whales are doing, the orcas in Puget Sound, and they're essentially starving because there's just not enough salmon for them to eat. And there's this renewed focus I think on creating salmon habitat to feed both the whales and of course ourselves, and beavers are a part of that solution and it might turn out that estuary beavers are a part of the solution as well.

BASCOMB: Wow. So help the beavers, help the whales?

GOLDFARB: Exactly, yeah. By helping the salmon.

BASCOMB: By helping the salmon, it's all connected. Now, you write about how beaver ponds can help restore degraded coastal wetlands. And there's clear evidence for that in removal of dams on the Elwha River in Washington State. Can you tell me about that, please?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, so the Elwha is a fascinating story. So the Elwha's a river on the Olympic Peninsula. And these two enormous dams had basically been there since the 20s I think, just trapping enormous amounts of sediment and blocking salmon runs. It was sort of this environmental disaster. And, you know, a few years ago the government actually bought those dams and -- thanks to pressure from native tribes -- and removed the dams, and opened up this huge amount of spawning habitat for salmon, so now salmon are swimming up river, past the former dam sites. But the kind of, the amazing outcome for beavers was that by breaching those dams we essentially unlocked this huge pulse of sediment, that had been trapped in the reservoirs and all this sediment just rushed downstream and basically settled at the mouth of the Elwha River. The river mouth had been starved of sediment for so long that it basically just flowed straight into the ocean. There was no real estuary there. Suddenly there's this huge beach and sandbar complex, about 100 acres of new habitat. And in the course of writing this article, I went out there and walked around on the kind of the Elwha floodplain, essentially, at the mouth of the river. And just everywhere you see cut willow and alder, and cherry; beavers are really going into town in there. And by creating burrows and canals and dams, they're just creating this amazing habitat complexity. They're just opening up lots and lots of little spaces for all kinds of salmon and trout and other fish to live in.

The mouths of the Elwha, Snohomish, and Skagit Rivers in Washington State provide important saltwater habitat for beavers, salmon, and many other estuarine species. (Photo: Illustration by Mark Garrison)

BASCOMB: Now you've written a whole book about how people are increasingly seeing beavers as hydrological saviors in freshwater ecosystems. What do you think it will take for them to gain that same recognition in their coastal contributions?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, that's a good question. I think that part of the issue is that we've lost so much of this coastal habitat here in Washington. These intertidal ecosystems are some of the first places that when colonists arrived, those habitats were essentially drained and converted into farmland, and we've lost about 95% of these kind of intertidal shrub-lands where beavers are so important. So I think that the first thing that has to happen is just a broader recognition of the, kind of the historical role of these intertidal ecosystems in producing salmon. And then once we've acknowledged that this habitat is so vital, then we can sort of start talking about how important beavers are there. Most of this research is sort of focused on beavers' role in tidal ecosystems in Western Washington, but are they playing a similar role in salt marshes in New England, or in the Carolinas, where beavers are really abundant, and where there are lots of salt marshes? We've lost so much of this intertidal habitat and we've lost so many beavers that, I think we've really lost a lot of these ecological linkages.

BASCOMB: Ben Goldfarb is author of the book "Eager: The Surprising, Secret Lives of Beavers and Why They Matter." He wrote about saltwater beavers for Hakai Magazine. Thanks for taking the time with me, Ben.

GOLDFARB: Thanks again for having me back.

Related links:

- Ben Goldfarb for Hakai Magazine | “The Gnawing Question of Saltwater Beavers”

- A previous Living on Earth interview about beavers with Ben Goldfarb

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Anna’s Hummingbirds Winter in the North

Most hummingbirds in the Northern Hemisphere migrate south for the winter, but the Anna’s Hummingbird sticks around as far north as British Columbia. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

BASCOMB: During the long, cold winters northern bird feeders could be graced with the usual suspects – blue jays, chickadees, perhaps a cardinal. But BirdNote’s Mary McCann tells us there are also some unlikely year-round residents.

BirdNote®

Anna’s Hummingbirds Winter in the North

[Male Anna’s Hummingbird singing]

On a chilly February morning near Seattle, with the temperature hovering below 40 degrees, a bird is singing lustily.

[Male Anna’s Hummingbird singing]

And not just any bird. It’s a hummingbird! A male Anna’s Hummingbird, whose throat and crown flash iridescent rose.

[Male Anna’s Hummingbird singing]

But what is a hummingbird doing this far north in winter?

While most hummingbirds retreat south in autumn, Anna’s are found in northern latitudes throughout the year. Since 1960, they’ve moved their year-round limit north from California to British Columbia. They’re taking advantage of widely planted flowering plants and shrubs as well as hummingbird feeders.

But how do they survive the northern cold? They seem unlikely pioneers, since hummingbirds have no down feathers for insulation and a metabolism that runs so high that they would exhaust their energy reserves on a cold night.

[Cold winter wind ambient]

The hummingbird’s solution? Suspend that high rate of metabolism by entering a state of torpor – a sort of nightly hibernation, where heart rate and body temperature are reduced to a bare minimum. Many hummingbirds, such as those residing in the high Andes, rely on the same strategy.

Yes, Anna’s Hummingbird has come north to stay.

[Wing whir of male Anna’s Hummingbird]

And its jewel-like presence at the nectar feeder adds sparkle to any winter day.

[Wing whir of male Anna’s Hummingbird]

I’m Mary McCann.

Anna’s Hummingbirds cope with the winter chill by entering a state of torpor, similar to hibernation, every night. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

#####

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Wing whir recorded by David Allen [6121]. Male Anna's Hummingbird song [111006] recorded by T.G. Sander.

Winter ambient C Peterson and Kessler Productions

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2019 Tune In to Nature.org February 2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/annas-hummingbirds-winter-north

BASCOMB: For pictures, buzz on over to our website, loe dot org

Related link:

Learn more on the BirdNote® website

BASCOMB: Next time on Living on Earth, One man’s quest to follow the migration route of the now extinct Great Auk.

O'CALLAHAN: He wanted to make a 1,500-mile kayak journey, from northern Newfoundland, all the way down to Buzzard's Bay. Well, I've grown up by the sea, and I knew that was almost impossible.

BASCOMB: Dick Wheeler’s not-so impossible dream. I’m Bobby Bascomb and that’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: John Scofield, “Southern Pacific” on A Go Go, 1998 The Verve Music Group, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc.]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Delilah Bethel, Paloma Beltran, Bobby Bascomb,Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. Also, you can find us on instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth