March 15, 2019

Air Date: March 15, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Youth Strike for Climate

View the page for this story

On March 15 an estimated million school children around the world went on strike for the climate, inspired by Greta Thunberg, who began striking outside the Swedish parliament during school hours in August of 2018 when she was fifteen years old. Anna Grace Hottinger helped organize the March 15 school strike in the US, and joined Host Steve Curwood to discuss the movement. (14:56)

Carbon Pricing and the Green New Deal

View the page for this story

The Green New Deal resolution recently introduced to Congress by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Senator Ed Markey (D-MA), calls for the U.S. to quickly decarbonize its economy. The resolution does not mention of carbon pricing, despite much interest among economists for carbon pricing, such as taxes, fees or cap-and-trade regimes. Stephen Stromberg, an editorial writer for the Washington Post, talks with Host Steve Curwood about why the Post urges that any Green New Deal put a high price on carbon rather than impose government mandates to encourage decarbonization. (07:23)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to dish out the disappointing truth about air-purifying houseplants. Then, they dive into how illegal gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon plays into deforestation. And then, from the history vault, they look back to 2009 when President Barack Obama signed the Omnibus Public Land Management Act. (04:35)

BirdNote®: How a Bird Came to Look Like a Caterpillar

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The Amazon rainforest is home to a wide array of fantastically-attired species. Among them is a bird whose chick, incredibly, looks like a caterpillar! BirdNote’s Michael Stein explains how evolution has driven a phenomenon called Batesian mimicry, in which certain species try to trick their would-be predators into thinking they’d make for a dangerous meal. (01:52)

“Hockey Stick” Climatologist Wins Tyler Prize

View the page for this story

Climatologist Michael Mann is the co-recipient of the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, considered by some as “the Nobel Prize for the environment”. In a conversation with Host Steve Curwood, Prof. Mann recounts his research that led to the famous “hockey stick” graph showing rapid global temperature rise, and the ensuing attacks on his scientific research and reputation by climate deniers allied with fossil fuel interests. Michael Mann also discusses his latest research findings and the promising new generation of science communicators. (18:17)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Anna Grace Hottinger, Michael Mann, Stephen Stromberg

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Young activists skipped school and took to the streets in more than 100 countries on March 15 to protest inaction on climate change.

HOTTINGER: There's really no point studying for a future, and a job that might not even be there because of what could happen. This is what being-a-teenager reality is for me; to create better change in the world, because my adults don't seem to be leading that.

CURWOOD: Also, why the Washington Post editorial board says any Green New Deal should put a price on carbon.

STROMBERG: In the ambitious scheme we're talking about, we're not talking about a small price on carbon. We're talking about a substantial price on carbon, a higher price on carbon than we've seen anywhere else before. One that would be much more effective at really fighting the coal industry and making it less and less economical.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Youth Strike for Climate

Young people on strike for the climate gather in the Karura Forest in Nairobi. (Photo: Flickr, UNEP, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On Friday March 15th as many as a million school children in as many as 100 different countries lined up for the school strike for the climate. They demonstrated from Honolulu to Holland to Hong Kong.

[CROWD CHANTING] What do want? Climate action! When do we want it? Now!

LILY: As you can tell, we’re in the Hague! It’s a global school strike today, so that we can make politicians wake up and do some action!

CURWOOD: At age 10 Lily marched in The Hague, as others spoke out in New Delhi and London.

BOY: Today, as you can see, a lot of people have come here and this movement has really gained momentum, even in Delhi. What I initially felt was that in India people are completely in denial of the fact that climate change is a thing. But as you can see, they’ve really, you know, made people get their voices heard. And we really spread this idea across, that change is possible.

[CROWD CHANTING]

ALICE: Alice, I’m 17. I came here because it’s scary, what’s happening to the world. It’s really scary, and no one is fixing it so we might as well try.

A student climate striker in Nottingham, England (Photo: kthrnr, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

REPORTER: How much do you think they’re doing right now?

ALICE: Nothing, they’re doing nothing. And they’re busy, I get that, Brexit’s happening. But they should be doing more because this isn’t going away anytime soon.

GREG: I’m Greg, I’m 16. I came here because there is a lack of action on climate change and it’s the most important issue at this day. The government needs to declare a climate emergency as soon as possible because we are seeing no action being taken and it’s ridiculous. We just need to show the government that this is an issue we really care about, because they’re ignoring us, essentially, and this is showing we care about this and it’s a huge issue. I worry that even if we stick in school and we get our educations that we won’t be able to get jobs, because the whole industries will be affected, everything’s going to be affected in the future. We’re going to see irreversible results of climate change if we don’t take action now, so it needs to be done. I’ll keep coming until more radical action is taken. My school isn’t totally supportive of it but at the end of the day, this is a bigger issue than my education.

LOOK AT THE SIZE OF THE MARCH IN BRUSSELS!!! Young people are rising in 2052 places in 123 countries on every continents.

— Mike Hudema (@MikeHudema) March 15, 2019

There is no time to waste. We must #ActOnClimate. #climatestrike #klimaatstaking #FridayForFutures #GreenNewDeal @GretaThunberg ???? via @JohnHyphen pic.twitter.com/3CGLMDYE8v

CURWOOD: Their common demand is simple. Take action now while there is still time to avert the worst possible effects from climate disruption. This is a growing movement. Students from roughly 1000 different schools in the US alone joined the school strike. And in South Africa, young climate champions gathered next to Parliament in Cape Town.

[CHANTING AND DRUMMING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The spark for the strike comes from Swedish student Greta Thunberg, who in August of 2018 at the age of 15 began skipping school and sat down in front of the Swedish Parliament. She was angry that Sweden would not meet its targets under the Paris Climate Agreement. Until the Swedish election on September 9th, she sat with a simple handmade sign proclaiming she was on a “school strike for the climate”. Every Friday following the elections, she has kept the strike going and inspired students around the globe to join her. By the way, Greta Thunberg is a distant relative of Nobel prize winning chemist Svante Arrhenius, the man who a century ago famously made calculations that showed increasing carbon dioxide emissions would lead to a warming world. And some people think Greta herself should get the Nobel Peace Prize. By December of 2018 she was invited to speak at the UN Climate Treaty negotiations in Poland.

Youth in 2 052 places in 123 countries across the globe are taking a stand demanding #ClimateAction!???? ???? ????.

— Greenpeace Africa (@Greenpeaceafric) March 15, 2019

Students outside parliament in #CapeTown making their voices heard.#FridaysForFuture #SchoolsStrike4Climate #ClimateStrike #Fridays4Future

Video source: .@AshrafRSA pic.twitter.com/aM5TitsPWz

THUNBERG: You only talk about moving forward with the same bad ideas that got us into this mess, even when the only sensible thing to do is pull the emergency brake. You are not mature enough to tell it like it is -- even that burden you leave to us children. But I don’t care about being popular, I care about climate justice and a living planet. Our civilization is being sacrificed for the opportunity of a very small number of people to continue making enormous amounts of money. Our biosphere is being sacrificed so that rich people in countries like mine can live in luxury. You say you love your children above all else, and yet you are stealing their future in front of their very eyes. Until you start focusing on what needs to be done, rather than what is politically possible there is no hope. We have not come here to beg world leaders to care. You have ignored us in the past and you will ignore us again. You have run out of excuses and we are running out of time. We have come here to let you know that change is coming, whether you like it or not. The real power belongs to the people. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Greta was more enthusiastically welcomed by the European Economic and Social Committee in Brussels in February of 2019.

[APPLAUSE]

THUNBERG: And if you think that we should be in school instead, then we suggest you take our place in the streets, striking from your work. Or better yet join us so we can speed up the process. And if you still say that we are wasting valuable lesson time, then let me remind you that our political leaders have wasted decades through denial and inaction. And since our time is running out we have decided to take action. We have decided to clean up your mess and we will not stop until we are done. Thank you.

Greta Thunberg sparked the School Strike for Climate movement, which began in August of 2018 when she began protesting Sweden’s lack of compliance in the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Anders Hellberg, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

[APPLAUSE]

[CROWD SINGING]: We want change, we want change. We want to save the human race…

CURWOOD: The majority of the million or so students around the world who went on strike for the climate March 15th appear to be young women, and a US organizer was 16-year old Anna Grace Hottinger of Shoreview, Minnesota. She joins us now. Anna Grace, welcome to Living on Earth!

HOTTINGER: Hi, thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: In your own words, please tell me about the Fridays for Future movement.

HOTTINGER: Yeah. So Fridays for Future was started by Greta Thunberg because Sweden was not on the Paris Agreement, and she wanted them to get back on board with them. And so Fridays for Future was started by her, because she strikes from school every Friday and went to the parliament. And it has now been brought forth to places all around the world. So people can join along and strike every single Friday, because striking is more important than education, if you might not have a reason to have that education in the future.

CURWOOD: Indeed. How concerned are you personally about this? What's the threat that you feel personally from climate disruption?

HOTTINGER: I personally just feel like I may not be able to see it in my own eyes in the future, because I am privileged enough to be able to move out of these situations. But also, that it soon won't be something that that we can shift out of, which is a very scary thing. Because no matter what, we'll all be stuck with this issue. But I see that we have the potential in it.

CURWOOD: So you say you're privileged to be able to move out of this. What do you mean?

HOTTINGER: The wildfires, for example. In California, people were able to hire private firefighters, and people to rebuild their giant houses, whereas other people couldn't move back to their houses. And you see that in hurricanes, and earthquakes, and all these sorts of things where people are able to move out of those situations and find a healthier and sustainable way to live. Whereas other people are not privileged enough to be able to go out of those places.

CURWOOD: Anna Grace, tell me the moment that you said, I have to do this.

HOTTINGER: Wow. So, I’m a big economy person, I love economics. And I looked into it, because I realized that the economy would be kind of screwed up. And then a few weeks later, my sister was actually in the California wildfires. And I hadn't done anything yet. But I decided that that's when I needed to do something, because this is an effect of climate change.

CURWOOD: Your sister was in the California wildfires. How is she?

HOTTINGER: She is doing great. She was evacuated from campus, but she's doing okay now. And it was definitely a rough semester for everybody around her.

I can't believe how big the #ClimateStrike is here in London. It's huge. It's been carrying on up the mall for ever. This is just incredible. They're so loud and so awesome. pic.twitter.com/XKVVCS2Yj0

— Dr Nick Crumpton (@LSmonster) March 15, 2019

CURWOOD: So, how did you get involved in the US climate strikes - the ones inspired by Greta in Sweden?

HOTTINGER: Yeah, so I got involved because I am in Minnesota Can't Wait, which is a Minnesota climate group. And somebody had reached out saying that there's this big thing coming up inspired by Greta that was going to be global, and everybody was going to be involved in it. And they were looking for some people to help out. So I just kind of jumped on the bandwagon. And it was an easy way in, and now we're doing great things.

CURWOOD: So, what's the message that you are hoping that these school strikes will send?

HOTTINGER: So, I'm hoping that, and we are hoping that, this message will be that climate change is urgent. And that by causing social disruption, such as leaving school in big numbers, will make it so it's a forceful thing that we need to look into. So for example, the March for Our Lives, when students left school, that caused a lot of stuff, and a lot of media attention came out. And so knowing that this is an urgent matter, and putting it on the table and making it clear to adults, that this is something that the youth care greatly about.

CURWOOD: So, what's the risk to you personally, about not going to school? You're supposed to be at school on Friday.

HOTTINGER: Yeah, so the risk of not going to school. I personally don't have any punishments, though, I do miss school a lot for this type of stuff. And it does tend to backfire on all of my academic things, such as my grades and my school attendance, which I wouldn't say is the most superb out of all the school attendance there.

CURWOOD: And it's worth it because?

US Youth Climate Strike organizer Anna Grace Hottinger is a sixteen-year-old activist. (Photo: Courtesy of Anna Grace Hottinger)

HOTTINGER: It's worth it because this is a future that I'm fighting for, and helping lead for not just myself, but for so many other people. It's not just about me, but also there's really no point of studying for a future and a job that might not even be there because of what could happen.

CURWOOD: The Fridays for Future website lists some hundred countries participating in the March 15 school strike, the Friday strike, with over 1000 events in different cities. How does it feel to be part of a truly global movement?

HOTTINGER: It feels fantastic. And it feels really cool, though I'm not doing this to get attention, because the reason we're doing this is to bring climate change to the front and center. But it feels really good, because without youth such as me, and such as Greta, and such as all the other leaders, we wouldn't have been here. And these policies that are coming forward wouldn't be here either.

CURWOOD: Anna Grace, I'm sure you understand that March 15 isn't going to bring instant victory for this movement. How long do you think it will take? And then what will it look like when you've arrived at the place you're looking for?

HOTTINGER: So I think one time, like March 15, will not create the change. And what will make that happen is by going every Friday to a local place and striking, and by making your actions heard and seen, and that is how the change will come. But I think that when it happens, we're going to have lawmakers and leaders who are on board with us. And we are going to be having all kinds of goals, such as being carbon neutral, being on the Paris Climate Agreement, and so many more things. And that is what accomplishment will look like. But it'll only look like that if we keep persisting, keep showing up and keep making our voices heard.

CURWOOD: What do your friends and family think about you being, well, really a leader and a spokesperson now for this movement?

HOTTINGER: So, my friends and family are very proud of my accomplishments. They usually are like, Oh, that's really cool Anna Grace, like, we're glad you're doing this. But sometimes it does get very frustrating because I spend my evenings going to meetings. So I'll go to meetings from 4:00 until 9:00, and I won't be able to go out to dinner, or go out to the movies with my friends, or go on trips with my friends, which it does break some social relationships, but they do recognize that this is a big deal.

CURWOOD: To what extent are people saying, Anna Grace, you're obsessed with this thing, lighten up!

HOTTINGER: Right now. It’s like, the biggest thing that my mom always tells me is that I need to lighten up and be more positive about it. And to live a life as a teenager.

CURWOOD: And you say?

HOTTINGER: And I always say that I do need to live a life as a teenager. But this is what being-a-teenager reality is for me, because I'm caring for everybody around me to have those teenage years, but also to create better change in the world because my adults don't seem to be leading that.

This #climatestrike march in #Dublin is huge! pic.twitter.com/9SlO1KsnOt

— Brian McDonagh (@brianmcdonagh) March 15, 2019

CURWOOD: Anna Grace Hottinger is a sophomore at EdVisions Off-Campus charter school in Shoreview, Minnesota. Anna Grace, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HOTTINGER: Yeah, thank you so much for having me, and making my voice heard, and our movement’s voice heard.

Related links:

- US Youth Climate Strike

- The Nation | “On March 15, the Climate Kids Are Coming”

- CNN | “Global Climate Strike: Students Around the World Protest Climate Inaction”

[MUSIC: Sing for the Climate Belgium – Final Clip, “Do It Now”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XGgBtHoIO4g]

CURWOOD: Coming up - The Washington Post editorial board on how to make a green new deal. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hanneke Cassel, “Captain H. Munro/Veronica’s Trip To Sophia Antipolis” on Trip To Walden Pond, Cassel Records]

Carbon Pricing and the Green New Deal

The Green New Deal put forth by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) does not mention putting a price on carbon. (Photo: Senate Democrats)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Green New Deal resolution recently introduced by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts, both Democrats, has attracted a lot of attention for its bold proposals to transform the U.S. economy. Many like its calls for moving to a 100% carbon-free electric grid in just ten years, as well as for a federal jobs guarantee and healthcare coverage for all Americans. But the AOC-Markey Green New Deal Resolution has also attracted criticism for going too far and being politically untenable. And some point out that their Green New Deal doesn’t even mention strategies like putting a price on carbon. The Washington Post Editorial Board recently laid out its argument for a Green New Deal that includes carbon pricing and stops short of broad progressive goals. Stephen Stromberg of the Washington Post authored the editorial. Steve, welcome to Living on Earth!

STROMBERG: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you this, how do you explain carbon pricing not being in the Green New Deal?

STROMBERG: So it's a very good question, because when you look at Ed Markey, for example, one of the co sponsors of the resolution, he co sponsored a carbon pricing bill in 2009, 2010, the Waxman-Markey carbon pricing bill, it was the premier global warming climate change legislation of the Obama era. It didn't pass. So there's been some hand wringing among environmentalists about the political attractiveness of a carbon pricing type program. On top of that you also have some who for a long time have been wary of carbon pricing, either through a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade program like California has, for a variety of reasons. Some people are more skeptical of market-based mechanisms and they prefer government mandates, and that's for sort of ideological reasons. Some people feel as though carbon pricing won't be effective enough in spurring research and development. And some people don't like the idea that companies would be able to pay to pollute, that it's not punitive enough, that pollution should not be something that you just get a fee for, but something that society should be saying is a shame, a problem. We accept that that's one way to look at it. But another way to look at it is, actually what it's doing is it's ramping down carbon emissions over time, it's doing so in a cost effective way, it's marshaling every dollar to its highest benefit. So if you can get over the discomfort of this appearance that companies are paying to pollute, what in fact you get is a highly effective, highly efficient system to get very far and in fact, we think where you need to be to fight climate change.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a common criticism about carbon pricing, and that's if it's not implemented well, it can perpetuate economic and public health inequities. That coal fired power plant next to a low income neighborhood that pays to continue its emissions means that people there are still going to breathe lousy air. How do you make sure that carbon pricing doesn't perpetuate economic and social inequities?

A carbon fee and dividend program, like the one recently introduced to Congress by Rep. Ted Deutch (D-FL), would return some or all of the money gathered to U.S. citizens. (Photo: Felix Jörg Müller, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

STROMBERG: Yeah, that's actually a very good point. And I should have said, that's another one of the reasons that there has been some skepticism around the carbon pricing type programs. So you have to do a few things. In any carbon pricing system, you're going to end up with revenue, the government will end up with revenue. And so one of the big questions is how you spend it, how you use it. And a slice of that revenue undoubtedly has to be spent on helping particularly low income people cope with the transition. So what that looks like is it could be rebates directly to Americans. It could be pumping up the earned income tax credit, which is a credit for the working poor. It could be a variety of other ways to feed back, recycle back, this revenue back into Americans' pockets. And this does a couple of things. One thing is it makes sure that low income, middle income, even some high income people who will be paying more in energy prices, in prices at the pump, will not be harmed by the energy transition. In fact, there's been study after study showing that people can be made whole if not better than whole, if you have this type of rebates system. Now, you bring up another point though, which is that if coal plants continue to produce emissions or other type of polluting industries continue to be able to do what they're doing, they'll also produce ambient pollution that's unhealthy for people. That's a substantial problem. So in the ambitious scheme we're talking about we're not talking about a small price on carbon, we're talking about a substantial price on carbon, a higher price on carbon than we've seen anywhere else before. One that would be much more effective at really fighting the coal industry and making it less and less economical, not to mention other industries that produce carbon emissions in various ways.

CURWOOD: And one of the themes of the Green New Deal is that massive public investments are needed for big mandates like high speed rail, for example. Your essays in the Washington Post editorial page say that's a bad idea.

STROMBERG: Yeah, we single out high speed rail, in part because of the spectacular failure that you just saw in California on the high speed rail front. And despite this, it's still in the resolution as an important piece of the Green New Deal goal, which, to us signified an insensitivity to the lessons of recent government waste. That's what we're really worried about, is this idea that the government will spend a large amount of money, will muster man-hours and resources toward projects that seem like they might help in this really important fight, but then they end up not helping. High speed rail is just one example. All that said, we believe that there does need to be in some cases direct government spending and intervention beyond a carbon pricing plan. So for one thing, we believe that local public transportation, you need to provide good alternatives, reliable alternatives to cars, and the government has to provide that, particularly for the low income who can't afford just to Uber everywhere or something like that, or can't afford to pay higher gas taxes. You need to provide research and development funding much more than what we're doing now, so that you can develop the technologies that are going to get us out of this carbon rut. You need to provide efficiency standards so that appliances and cars will get more efficient. A carbon pricing program would do some of that but it wouldn't get you as much efficiency as you might need. You get greenhouse emissions in cement making, in some other industrial processes; you'd have to have some kind of response to that, tailored to each of these sectors. So there are gaps in a carbon pricing system. You do have to have some willingness to set mandates, some willingness to spend money, just, we believe that that shouldn't be the first impulse. That should be sort of the backup impulse after you've put carbon pricing system in place.

CURWOOD: Stephen Stromberg is an editorial writer for The Washington Post's opinion section. Steve, thanks so much for taking the time today.

STROMBERG: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Washington Post Opinion | “Want a Green New Deal? Here’s a Better One.”

- Read the Green New Deal Resolution

- The Energy Innovation and Carbon Dividend Act is a bipartisan carbon pricing plan

[MUSIC: Lake Street Dive, “Dupont” on Promises, Promises, self-published]

Beyond The Headlines

Peace Lilies are lovely, but can only offer a tiny amount of air-purifying for households, recent research says. (Photo: Flickr, Shawn Harquail, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We're going to start with a little episode of scientists being scientists. Back in 1989 there was a NASA scientist named William Wolverton. He was involved in research on house plants and their ability to clean and purify indoor air. What he came out with was a real boost for the house plant industry. It helped it grow to $47 billion annually, just in this country. There was a real rush in the 90s and early 2000s to buy indoor houseplants under the assumption that they clean things like the volatile organics that would come from paint and carpet and all the other things that go into modern living.

CURWOOD: Yeah, we were excited about that, we had him on Living on Earth back then, he listed a whole bunch of plants that would help clean up the air in your house. But I guess new research says something a little different?

DYKSTRA: That was your basic 20th century science. And here's the 21st century. There's recent research from Drexel University, actually a meta study in which they reviewed about 150 scientific works on houseplants and indoor air, and they discovered that you'd have to have an absolutely ungodly number of houseplants in a room to match the air purifying value of either just opening a window or having a clean filter and a properly functioning HVAC system.

CURWOOD: How many plants you talking about, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Enough plants that you couldn't fit yourself in the room.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

DYKSTRA: That doesn't mean that houseplants are bad, I like the ones that I have. There's no reason not to have a Ficus or a Peace Lily or anything else you want to put in your room. But don't expect them to clean your air.

CURWOOD: Alright, so I'm going to keep my Peace Lily and my dracaena, but they're there for their beauty not for their work. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Satellite monitoring is used for a lot of environmental context. It's really been a help to monitor the open oceans for illegal fishing, remote lands for illegal logging and mining. But one of the latest revelations as reported by the website Mongabay shows a rampant increase in illegal logging in the Peruvian Amazon. And not only is there logging in the rainforest, but the reason that this logging is going on is to enable illegal gold mining.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh, gold mining is really very dirty. I mean, they use all kinds of things like cyanide to try to strip the gold out of the ore. It can be really, really hard on a wild place.

DYKSTRA: Yeah. It's an environmentally filthy business and to denude the rain forest to make it happen in the first place has its own really dire consequences. It’s estimated that somewhere between 6000 to 7000 people have moved into some lands that were once pristine and wild bordering a Peruvian National Park, a nature preserve and some native areas. There are allegations of massive corruption on the part of the previous national government in Peru along with current local governments.

The Tambopata River in the Peruvian Amazon, threatened by mining. (Photo: Flickr, Joseph King, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hmm. Hey, what do you have from the history vaults for us?

DYKSTRA: 10th anniversary of something with kind of an obscure bureaucratic name. In late March 2009, President Obama signed a bill, Congress passed a bill, that gave the highest level of protection to 2 million acres of land in parcels all over the United States. That bureaucratic name was the 2009 Omnibus Public Land Management Act.

CURWOOD: And what did it protect?

DYKSTRA: Well there were areas that already had some protection. Some national parks, refuges and elsewhere that went, ranged from the Appalachians in West Virginia and Virginia; around Mount Hood in Oregon; the San Gabriel Mountains outside LA; the Pictured Rocks Lakeshore in the Great Lakes; Rocky Mountain National Park and other sites. 2 million acres added to protected lands. That's something that's not really going on in the current day and age.

Parts of Picture Rocks National Lakeshore in Michigan received wilderness designation in the 2009 Omnibus Lands Act. Miners’ Castle in the Lakeshore suffered the collapse of a turret in April 2006. (Photo: Charles Dawley, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: That's right. And just a reminder to folks that a wilderness protection means that you can only walk or take a horse. You can't bring any motor vehicles or anything like that into those areas.

DYKSTRA: Nothing at all. It's the highest level of absolutely pristine protection we have.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks Peter, Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories and our website loe.org.

Related links:

- The Atlantic | "A Popular Benefit of Houseplants Is a Myth"

- Mongabay | "Record levels of deforestation in Peruvian Amazon as gold mines spread"

- CNN Politics | "Obama signs sweeping public land reform legislation"

BirdNote®: How a Bird Came to Look Like a Caterpillar

The Cinereous Mourner (Laniocera hypopyrra) is a quintessential example of Batesian mimicry, the disguise that some harmless creatures adopt in order to trick would-be predators into thinking they’re dangerous. (Photo: © David R. Santiago)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: The unique evolutionary pressures of life in the Amazon rainforest

have spawned an incredible array of fabulously-attired animals. BirdNote’s Michael Stein tells us about a colorful bird that evolved to mimic… a caterpillar.

BirdNote®

How a Bird Came to Look Like a Caterpillar

STEIN: In nature, one way to avoid being eaten is to look like something you’re not—ideally, something that tastes really awful — or that might even kill you.

Science calls this Batesian mimicry, named for a 19th century naturalist. Bates found that some perfectly edible butterflies had evolved color patterns that mimic those of toxic butterflies, which predators avoid.

Well, these butterflies are not alone.

The Cinereous Mourner is a small, ashy-gray bird that lives in the forest understory of the Amazon Basin. And it’s taking mimicry to the next level: its chick looks like a poisonous caterpillar!

[Cinereous Mourner call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/98606, 0.10-.14]

The chick is covered in vivid orange feathers punctuated with black dots. Lying alone in its cup-shaped nest, it’s a near match to a highly toxic caterpillar — one that snakes and monkeys won’t eat. The chick even waves its head like a caterpillar, increasing the illusion.

Cinereous Mourners live in an area where many birds’ nestlings are routinely lost to predators—and this may explain how a bird wound up dressed as a deadly caterpillar.

[Cinereous Mourner call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/98606, 0.10-.14]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by ML 225024 B. Oshea and ML 98606 D Finch.

BirdNote’s theme music composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler; Managing Producer: Jason Saul; Editor: Ashley Ahearn; Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone; Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill.

© 2019 Tune In to Nature.org March 2019 Narrator: Michael Stein

https://www.birdnote.org/show/how-bird-came-look-caterpillar

CURWOOD: For pictures, fly on over to our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote® website

- More about the Cinereous Mourner from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Thelonious Monk, “Dinah (Take 2)” on Solo Monk, by H.Akst/S.Lewis/J.Young, Columbia/Legacy Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Climate scientist Michael Mann on winning the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement after years of attacks from the fossil fuel industry. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thelonious Monk, “Dinah (Take 2)” on Solo Monk, by H.Akst/S.Lewis/J.Young, Columbia/Legacy Records]

“Hockey Stick” Climatologist Wins Tyler Prize

Warren M. Washington, left, and Michael Mann, right, are the 2019 recipients of the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn / Tyler Prize)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement recognizes outstanding scientists. And past recipients have included E.O. Wilson, Roger Revelle, and Jane Goodall. For 2019, two atmospheric scientists share the Tyler Prize: Warren M. Washington, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and climatologist Michael Mann, Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. Professor Mann has been a regular guest on this show to explain what’s going on with climate disruption including hurricanes, wildfires, heat waves, and the polar vortex. Beginning in the 1990s, he got attention for developing the "hockey stick" graph that starkly depicts the recent rapid increase in average world temperature. But his climate research has also earned him the ire of the fossil fuel industry. Michael Mann joins us now in our studio. Welcome back to Living on Earth -- and congratulations!

MANN: Thanks so much, Steve. Really appreciate that.

CURWOOD: So, you're famous research-wise for doing what some folks would call paleoclimate work. That is, you look back at what happened hundreds, thousands of years ago to say what might be happening in the future. Talk to me about that. And why did you become intrigued with that?

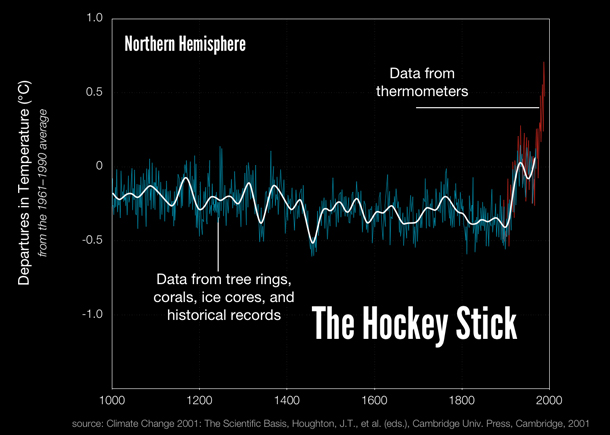

The famous “hockey stick” graph, showing time reconstructions [blue] and instrumental data [red] for Northern Hemisphere mean temperature. In both cases, the zero line corresponds to the 1902-80 calibration mean of the quantity. Raw data are shown up to 1995. The thick white line corresponds to a lowpass filtered version of the reconstruction. (Photo: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis, Houghton, J.T., et al. (eds.), Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2001)

MANN: Yeah. So what we did is we used all the natural archives that we could get our hands on: tree rings, of course, tell us something about past conditions related to tree growth -- rainfall and temperature. So we can glean information about climate from the thickness and even the density of the rings in tree cores from sort of continental, extratropical locations. Tropical trees aren't useful for tree ring research. So you're only getting information really from the extratropical continents, and that's not the whole planet, right? So you need to fill in those gaps. Well, we do that by using other data like ice cores, which come from high latitudes or even in some cases the tropics, at very high elevations, like Mount Kilimanjaro or in the Andes. So now you're starting to fill in those gaps. You've got the tropics, you've got the polar regions, then the oceans; well, we can turn to corals. The calcium carbonate skeleton of a coral contains, typically, annual growth rings. And we can look at the isotopes of oxygen in those growth rings; that tells us something about the seawater that that coral was growing in. And so what our project was about was taking this increasingly rich information coming from scientists around the world producing these different kinds of records, and assimilating them into a single reconstruction of past large-scale temperature patterns around the globe. Now to us, the most interesting thing about those reconstructions was what we could learn about the regional patterns of past climate -- the El Nino phenomenon; what happened during the largest prehistoric eruptions. It was those sort of regional patterns that we were really interested in, what they could teach us about climate dynamics. But what ended up becoming by far the single most prominent aspect of that research was what happens when you average over all of the regions, you average away a lot of those interesting details. And you come up with one number for each year, the average temperature of the Northern Hemisphere. And we could plot that back in time. And when you do that, what you see is that it was relatively warm about 1000 years ago. And then we descended into the depths of the Little Ice Age, in the 17-, 18-, 1900s; and then we see this warming spike, of the past century. And it is so sharp that it takes us well outside of the range that we see over the past thousand years. So laid on its side, it looks like, you know, the sports implement that we refer to as a hockey stick. And that's the name that it got, and the name stuck.

CURWOOD: So you do this research, you publish this research; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change uses the hockey stick chart as part of its summary in 2001, big assessment; and you go get a job at the University of Virginia. And then... trouble.

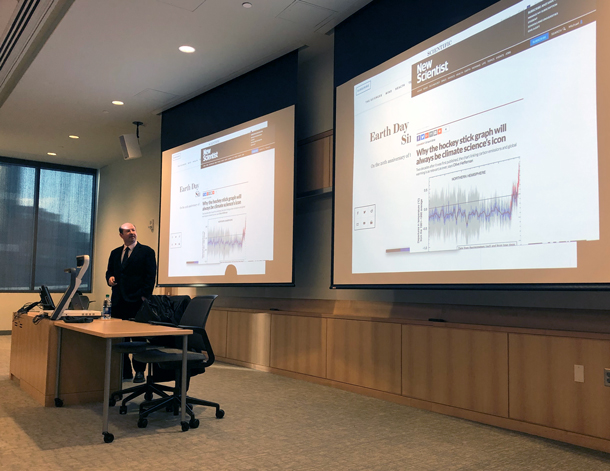

Michael Mann was invited to give a lecture about climate change impacts at the University of Massachusetts Boston on March 5, 2019, by the university’s School for the Environment. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

MANN: Well that's right; you know, I was subject to sort of this crescendo of attacks on the hockey stick, but often on me personally -- efforts to discredit me and thereby, you know, presumably discredit this iconic curve, the hockey stick curve, this symbol in the climate change debate. There, you know, started to be op-eds and editorials attacking the hockey stick and me, in conservative media venues, The Wall Street Journal for example. And all of that was happening about the time I arrived at the University of Virginia. And I'm trying to of course acclimate to this new role, this new job that I had as a professor, I've got to teach and advise students, and I'm juggling all that. But I'm also sort of dealing with the increasing amount of publicity surrounding the hockey stick curve. Pretty soon, I would find myself at the receiving end of attacks by prominent politicians closely tied to fossil fuel interests, like James Inhofe of Oklahoma, who has dismissed climate change as the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people. Back in 2005, the head of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Joe Barton, a Republican from Texas, very closely tied to fossil fuel interests, tried to subpoena all of my personal emails, and those of my two coauthors on the original hockey stick article; held a hearing, trying to attack the hockey stick. And typically these attacks would coincide with major policy developments. For example, there was an energy bill potentially dealing with climate change that was about to be voted on by the US Congress, and in advance of that Joe Barton, again, used -- or some would say, abused -- his authority as the chair of that influential committee to run a show trial attacking the hockey stick, and essentially go on this campaign of vilification against me and my coauthors.

CURWOOD: So famously, the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Virginia came after you, and people may or may not think of Virginia as a coal state, but they got plenty of coal out west of Virginia, the fossil fuel industry was very concerned about your research; and the Attorney General came after you. What was the accusation and what happened as a result of those accusations?

MANN: Yeah. So this was Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, who is often referred to as a Tea Party Republican, elected in 2009; attempted to subpoena my emails using what's known as a civil investigative demand, which exists in Virginia law so that the attorney general can ferret out state waste and fraud. And so what he tried to argue with that the science of climate change is fraudulent -- dismissing of course the overwhelming consensus of the world's scientists -- and thereby arguing that he could use this investigative demand which was really designed to deal with Medicare fraud. But nonetheless he attempted to use this as a cudgel, to go after me and my coauthors, much in the way that Joe Barton before him had done. Again, Ken Cuccinelli, conservative Republican who was heavily funded by some of those fossil fuel interests, including coal interests, which do have an influential role in the state of Virginia.

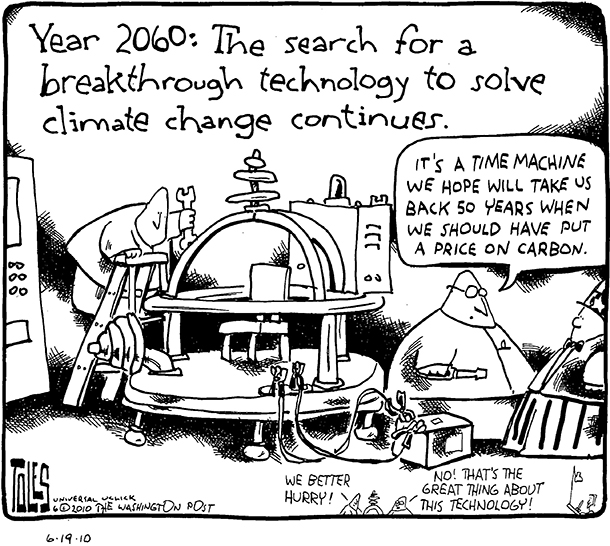

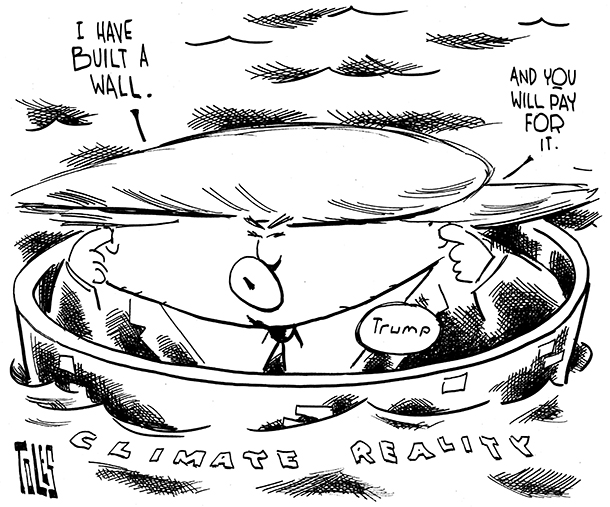

Michael Mann and cartoonist Tom Toles coauthored the book “The Madhouse Effect: How Climate Denial Is Threatening Our Planet, Destroying Our Politics, and Driving Us Crazy”. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

CURWOOD: This wasn't a small case, I mean, it winds up in the Virginia Supreme Court; if not millions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of dollars being spent on legal fees, and what was the outcome?

MANN: Yeah, that's right. And the University of Virginia was forced to spend millions of dollars defending itself. It was very costly for them and a distraction for everyone. And in the end, it was dismissed by the lower court because they found that in his 40-plus page filing to the court he had failed to show any evidence of wrongdoing on my part, any evidence of any malfeasance at all. And so it was dismissed by the lower court. Cuccinelli challenge that decision, it went to the state Supreme Court, which ultimately rejected his case with prejudice, meaning, they never want to see an attorney general come to the court, come back to the court with something like that again. So that was a battle that we won. It was a battle that was won on the side of science and reason and logic and honesty, but it was just one in many skirmishes in this battle.

CURWOOD: The struggle in the courts of Virginia over your research got you a lot of attention in the United States, but internationally, you became famous, Michael Mann, because of an email hack. Tell me about that story.

MANN: Yeah, you know, there was a fair amount of attention in the US and internationally, drawn to this affair that came to be known as climategate -- ironically, because much like Watergate, the only real indiscretion, the wrongdoing, was the criminal theft of those emails in the first place. But what hackers working with, what were probably state actors, we now think--

CURWOOD: You're thinking Russians?

MANN: There's some evidence that Russia and Saudi Arabia were both involved in this, as a means of sort of thwarting progress at the 2009 Copenhagen summit. So the Copenhagen international climate summit in December 2009 was really the first opportunity in years for international policy action, for an agreement that would really help us tackle the problem of climate change. And fossil fuel interests and state actors working on their behalf, did everything they could to sabotage those proceedings. What they did: they combed through thousands of stolen emails, and looked for individual words or phrases that could be taken out of context to make it sound like scientists had been cooking the books, using words like "trick", which, a trick, in science means it's a clever way of solving a vexing problem. But to the person on the street, you take that out of context, you tell them, Look, these scientists are playing tricks, it's a way, again, to try to take the language of these scientists out of context, to misrepresent what they were doing, and to smear them and discredit them.

CURWOOD: Today, Michael Mann, how afraid are scientists of harassment and difficulties when telling the story of climate disruption?

MANN: I think that that is part of the purpose of these attacks, is to frighten especially young scientists, who might think of becoming more active in the public conversation about climate science and climate change. But in my view, I think it's had the opposite effect. I think the attacks have so enraged the scientific community, this assault on science. And, you know, some would argue that the assault on science that we were dealing with has now metastasized into something larger in our politics today, which is an assault on truth, objective truth, and facts. And if you don't like the facts, there are alternative facts, as we have come to know, that many people are willing to promote. So we've lost sort of this objectivity in our public discourse. In climate change, we saw that years before, we saw that, the thing that we're now seeing writ large in American politics was already happening there. And I think that that was truly distressing to scientists, the idea that the forces of science denial would sort of stoop to the most dishonest of tactics in an effort to discredit science itself. I think that that brought in a whole new breed of scientists who were not only passionate about science, but wanted to help defend it against these attacks. And now there is this cadre of young scientists coming up in the field who are extremely active when it comes to outreach and communication and it's become a very valued part of their identity as a scientist. And so I like to think that the attacks that were intended to frighten away would-be scientist communicators have instead led to a whole new generation of pretty thick-skinned scientist communicators who want to make sure that we have an objective conversation about the science and its implications.

"The Madhouse Effect" features incisive critique of prominent climate deniers. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

"The Madhouse Effect" features incisive critique of prominent climate deniers. (Cartoon by Tom Toles)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about today. What are your latest findings?

MANN: So I -- you know, most people when they think of me, they think of the hockey stick and they think of paleoclimate. But these days, my scientific interests are more focused on the impacts of climate change -- coastal impacts, understanding how climate change is impacting coastal storms, hurricanes and tropical storms, and how that is combining with global sea level rise to threaten our coastlines, with a focus on, you know, places like New York City that of course, have dealt with devastating recent coastal storms like Superstorm Sandy, unprecedented flooding. How much worse is that going to get? You know, what does the future look like? There's a lot of interesting scientific uncertainty there, particularly with respect to global sea level rise, because that depends on the stability of the ice sheets. And we're starting to learn that the West Antarctic ice sheet, the Greenland ice sheet, may be less stable to near-term warming than we thought. So there's a lot of uncertainty there. But it's not our friend. It means we could be in for far more damaging sea level rise impacts in the future. That's an area of interest to me, because it involves some really interesting science to understand how climate change is going to influence the characteristics of hurricanes, the frequency and the intensity and the size of these storms. There's a lot of really interesting underlying atmospheric physics there. I'm also very interested in the impact that climate change is having on extreme weather events in general, particularly summer weather extremes, like the sorts of droughts and heat waves and floods and wildfires out west that we've seen in recent summers. In fact, 2018 was sort of a poster child for how climate change is increasing many of these devastating extreme summer weather events. And our own research suggests that there are processes, fairly subtle physical processes involved, that are actually exacerbating these extreme weather events in a way that isn't captured in current generation climate models.

CURWOOD: Oh?

MANN: No - it has to do with some fairly subtle features, that have to do with waves in the atmosphere. In fact, in the March issue of Scientific American, I have an article about this phenomenon. It turns out, it's interesting scientifically, because there is actually a connection between these wave phenomena in the atmosphere and sort of the physics of quantum mechanics. And some of the mathematics we use to study this problem actually comes from math that was developed to solve problems in quantum mechanics.

CURWOOD: So you're talking about a new way of looking, really, at resonance, if I were to oversimplify it.

Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science and the Director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University. (Photo: Sydney Herdle)

MANN: Absolutely. What has made these extreme weather events so extreme, like last summer, summer 2018, was the fact that we had these exaggerated waves in the atmosphere. When you look at the jet stream and it wiggles north and south as it crosses the United States for example, those north and south wiggles are associated with high and low pressure systems. And the larger the wiggles, the bigger those highs and lows. Big high pressure gives you the sort of heat and dryness that yields unprecedented California wildfires like we saw this summer. But you get the flip side of that wave, you get the trough, the low pressure back east, and you get unprecedented rainfall. And we saw the wettest summer on record, where I live in Central Pennsylvania; I think Quabbin reservoir in the western part of Massachusetts reached the highest level that it has ever seen. And so what made those events so profound, so extreme, was both the large nature of the waves in the atmosphere that give you those big surface high and low pressure systems, that give you unusual weather, and the fact that they were very persistent, they just stayed locked in place. The ridges and the troughs basically sat over the same regions. That means those highs and lows are sitting over the same place, either baking you, or dumping rain on you, day after day. And that's when you get truly unprecedented weather extremes. That phenomenon, the waves getting larger, is a resonance phenomenon.

CURWOOD: So what should the public do now in response to your latest research?

Michael Mann and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MANN: Well, I think one thing that our work and a large family of research in this field has shown us in recent years is that uncertainty isn't our friend. As we begin to understand and better model some of these processes, we're not finding that climate change is less of a problem than we thought, we're finding in many cases that it's worse of a problem. The ice sheets can melt faster; that means we can get more sea level rise sooner than we thought. Climate change is exacerbating extreme weather events in a way that we didn't fully appreciate. But we're seeing play out in real time now on our television screens and our newspaper headlines. Uncertainty is not our friend. If anything, it's a reason for more concerted action. So when the critics say, well, there's uncertainty in the science, and they use that as a crutch for inaction --actually, uncertainty implies just the opposite. We want to take an insurance policy because of the potential for things to be far worse than even our current projections suggest.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University and a cowinner of the 2019 Tyler Environmental Prize. Professor, congratulations!

MANN: Thank you very much, Steve, it means a lot.

Related links:

- Michael Mann’s article in the March 2019 issue of Scientific American

- About Michael E. Mann and Warren M. Washington, 2019 Tyler Prize recipients

- LOE’s interview with Mann about climate change and 2018’s Hurricane Michael

- LOE’s interview with Mann on the release of his book “The Madhouse Effect”

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, “So What”, on Kind Of Blue, Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth