April 19, 2019

Air Date: April 19, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Exxon Sued Over Climate Risks of Storage

View the page for this story

Sea level rise and intensifying storms are putting coastal homes and ecosystems at risk including the potential for disastrous industrial spills. That’s the basis of a lawsuit brought by the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) against ExxonMobil, over the alleged vulnerabilities of the company’s Boston Harbor storage facility to climate disruption. A federal judge recently allowed the suit to go forward, and CLF President Brad Campbell talks with Host Steve Curwood about the risks of storm-induced spills that storage tanks pose to local communities and the fragile Boston harbor ecosystem. (07:28)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Looking beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra takes Host Steve Curwood to Norway, where the government has decided against investing in drilling in the oil-rich Lofoten Islands. The opposite may happen in Florida, as President Trump moves towards developing offshore oil and gas drilling. They then talk about President Trump’s attempts to weaken the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and look back on President Richard Nixon’s environmental policies, including the birth of NEPA. (04:19)

Earth Day Checkup

View the page for this story

Every April 22nd since 1970 we celebrate Earth Day. And since that first Earth Day much has been done to clean up our air and water, here in the U.S. and elsewhere. But the world isn’t yet curbing carbon emissions fast enough, and the leadership that the U.S. once showed on the climate crisis has almost vanished. Jonathan Pershing led the U.S. delegation to the UN climate talks during the Obama Administration and discusses with Host Steve Curwood the current global outlook for addressing climate disruption. (15:58)

BirdNote®: What’s Your State Bird?

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

State birds are usually among the more common species in a state, but not always, as with the endangered Nene goose of Hawaii. And as BirdNote®’s MaryMcCann reports, in some cases they aren’t even native to the North American continent. (01:57)

Prepping for the City Nature Challenge

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

The City Nature Challenge is an international contest known as a bioblitz - a brief, intensive survey of biological diversity over a set area and time. With a handy smartphone app, anyone can participate by cataloging the nature in their neighborhoods. The Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls took a trip out to Thompson Island in Boston Harbor to practice their observational skills before the competition begins. (02:14)

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

View the page for this story

Deep within the remote wilderness of the Alaska Peninsula, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is one of the least-traveled places within the national park system. Designated by President Jimmy Carter as a national monument and preserve in 1978, Aniakchak is always open to visitors with no amenities, no cell service, and no park rangers -- hence its slogan, “No lines, no waiting!” Chris Solomon, who wrote about Aniakchak for Outside magazine, joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his experience among the grizzly bears and volcanism in this wild and remote patch of public land. (11:22)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Brad Campbell, Jonathan Pershing, Chris Solomon

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Taking stock of our planet 49 years after the first Earth Day.

PERSHING: I think we've made some huge progress in some places around local pollutants. We've cleaned up a great deal of the U.S. waterways, we've got much better air than we had back then, although it's getting worse again; we're much better on things like mercury. But some of the other big problems? Not looking too good.

CURWOOD: Also, a trip to one of the most stunning and least-visited places in our national park system.

SOLOMON: You can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And, it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Exxon Sued Over Climate Risks of Storage

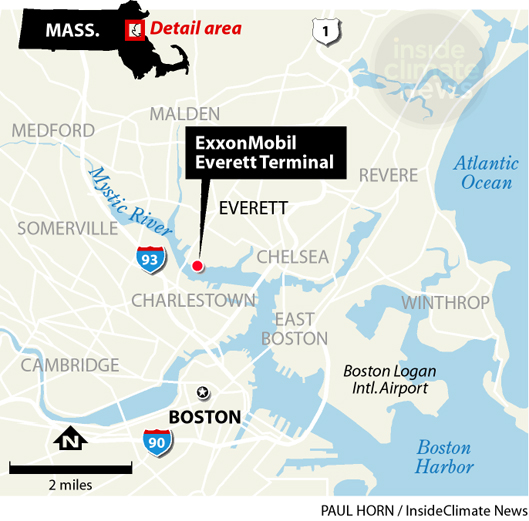

Even a Category 1 hurricane would inundate most of ExxonMobil’s Everett, MA oil storage facility. (Image: Courtesy of Conservation Law Foundation / USGS)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

ExxonMobil has another climate related lawsuit on its hands. Litigation alleging Exxon misled investors and the public about what it knew about the risks of climate change has been grinding on through the courts for years. And now a federal judge in Massachusetts is allowing a suit to go forward over climate risks related to ExxonMobil’s storage tanks near Boston Harbor. The Conservation Law Foundation alleges that the oil giant has failed to prepare an oil storage facility in Everett, Massachusetts against the stronger storms of climate disruption. Here to tell us more is Brad Campbell, the President of the Conservation Law Foundation. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

CAMPBELL: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about this ExxonMobil oil storage facility there in Boston. Where is it? And why are you concerned about the risks that that facility could pose to the community during an extreme weather event?

CAMPBELL: ExxonMobil has a large bulk terminal where they receive petrochemical products -- oil and other products. It's nestled right in the heart of a densely populated community. And it sits on a tributary to Boston harbor, which the public in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has spent literally billions of dollars to clean up, after a lawsuit that the Conservation Law Foundation initiated. So there's much at risk, both in terms of public safety, public health, public investment; and of course, the environment, if that facility were to be inundated, and that inundation were to lead to a catastrophic spill.

CURWOOD: So it's on a tributary; folks who know Boston would say it's on the Mystic River. How vulnerable is that spot, exactly, to sea level rise -- what kind of storm could bring a storm surge to this facility?

CAMPBELL: Every projection of a Category 1 storm puts this facility under water, fully inundated. And we've seen in Harvey, we've seen in Irene, we've seen in Sandy, that these are the types of tanks that collapse readily when there is an inundation of that nature. But there's a separate set of climate risks this facility is not addressing. And that's, that's the risk that we're seeing in the day to day now, with New England having a more than 70% increase in intense rains, where you get two or more inches of rain very intensely in less than 24 hours. This is a facility where, because it's been in industrial use for over a century, every drop of water that hits the ground has to be treated to remove very potent toxics, including a number of carcinogens. That rain pattern, that new rain pattern we have as a result of climate change, is overwhelming the treatment plant at this facility. And as a result, day in day out when these rains come, this plant is violating its Clean Water Act permit with major exceedances, in some cases, thousands of times their permitted level, of very potent toxics going into the Mystic River system.

CURWOOD: Now what specifically are these toxic chemicals? What are some of these oil products that ExxonMobil stores there; and talk to me, why they're dangerous?

CAMPBELL: Well, it's really a toxic stew that has to do not just with the oil that's stored there, but with the essentially century of use of this facility for various petrochemical products and hazardous substances. So some of them are very common things folks are familiar with: PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; benzene and toluene; xylene and so forth. But then there's also a more exotic set of very potent carcinogens that are showing up in the discharge monitoring reports that Exxon itself is self-reporting and that show very serious and very frequent violations of their Clean Water Act permit.

CURWOOD: So your lawsuit is at that typical stage in many lawsuits, just trying to get the right to have the lawsuit proceed to have a trial. But let's say that you get over that hurdle, there's a trial, and the court says, You're right, Conservation Law Foundation, this facility is, is not protecting the public in the way that it should. What's the remedy that you would like to have?

The ExxonMobil facility is situated right on the Mystic River, which joins the Charles River to form inner Boston Harbor. (Image: Courtesy of Paul Horn and InsideClimate News)

CAMPBELL: I think there are a number of remedies that have to be part of the solution here. One is that just as a matter of deterrence and example for other facilities, Exxon should have to pay civil penalties to the US Treasury for the hundreds of violations over hundreds and hundreds of days that have occurred at this facility that are alleged in our complaint. Secondly, they have to ensure that as we are now in this pattern of more intense rains, the improvements to their facility operation, mostly fixing their or upgrading their stormwater treatment system so that toxics are not washing off their facility directly into the harbor ecosystem. That's a second element of any remedy for this facility. And the third, of course, is implementing those safeguards, those protections that are needed from an engineering perspective to ensure that either the facility isn't inundated in the case of extreme weather that we know is imminent, or that if it is inundated, the tanks and the pipes and so forth are protected or designed in a way that they are essentially climate-ready.

CURWOOD: It would seem that protecting its facilities against the shift in climate would be in ExxonMobil's own interest. You're in court with them because you don't think they're prepared; why do you think they're not prepared?

CAMPBELL: Well, the sad fact is that it's in the public interest for them to harden this facility; in terms of their short term economic interests, which seems with Exxon to be paramount, you know, they're saving the costs of improving the treatment system, they're saving the costs of protecting the tanks from inundation. And in the event of a catastrophic spill, yes, Exxon will bear some costs. But the public will also be bearing a heavy cost. The families and businesses that will have oil and toxics flowing through their basements and into their homes, they will be bearing a cost. The taxpayers of the region, who paid billions to clean up Boston harbor, which is now a jewel of economic and urban rebirth here in Boston, they will suffer a terrible cost. Not all of those costs will fall on Exxon, and that's why it's important that we have statutes like the federal Clean Water Act. They require Exxon and other facilities like the one Exxon has in Everett to use best engineering practice. And best engineering practice means you look not just at what's happened in the past, but what the science tells you is already here in terms of the more intense rains, and that lies just ahead in terms of more intense extreme weather events coupled with rising seas.

CURWOOD: Brad Campbell is the President of the Conservation Law Foundation in Boston. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CAMPBELL: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: An Exxon representative says if the case had merit the EPA would be acting on it. But when we contacted the EPA a representative declined to comment on ongoing litigation.

Related links:

- Boston Globe | “Exxon suffers a big setback in climate-change case involving its Everett oil terminal”

- Read more about the Conservation Law Foundation lawsuit against ExxonMobil

- The text of the CLF lawsuit filed against ExxonMobil

- Listen to our previous interview with Brad Campbell when the lawsuit launched in 2016

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on Spirit, by Paul Simon (Jazz Legacy)]

Beyond The Headlines

Lofoten is an archipelago filled with beautiful scenery and history. Norway has abstained from oil drilling in this emblematic area, and is moving forward on keeping up with the commitments laid out in the Paris Climate agreement. (Photo: Melenama, Flickr, CC BY SA - 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's head down to Atlanta, Georgia now to talk with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with environmental health news -- that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org -- for a look beyond the headlines. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: But first, take a look out the window. Those magnolias are all blossoming there I imagine?

[BIRDSONG AND MUSIC: Rossini, William Tell Overture, “Morning Song”]

DYKSTRA: All the Magnolias are blossoming and you could inhale that sweet aroma of the magnolias, and you also get a nose full of pollen this time of year.

[MUSIC FADES]

CURWOOD: Hey, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, there are advocates of climate action, Bill McKibben is the most noteworthy, that have told us that in order to prevent the worst consequences of climate change, we're going to need to leave oil in the ground, large amounts of oil, or leave it under the sea. And you know what, Norway is actually doing that right now. The Lofoten Islands are an archipelago in the Arctic, Norway makes a bundle of oil elsewhere in places like the North Sea, they pull out over a million barrels a day, but in the Lofotens, it's estimated that there are one to three billion barrels of recoverable oil. Norway is gonna leave it right there under the sea and protect a pristine set of Arctic islands.

CURWOOD: But that's worth a lot of money. And they're doing this because?

DYKSTRA: They're partly doing this because they can, I mean Norway makes a lot of money off of oil. They have a huge pension fund, almost a trillion dollars. A lot of that comes from oil, but they have pledged that what they take in from oil is going to be reinvested in renewables.

CURWOOD: That's really an encouraging sign. What else do you have Peter? Any more good news?

DYKSTRA: No, not right now. Politico reported from some unnamed administration sources this week that the Trump administration is going to seek to auction oil and gas leases off of Florida, and that's both the East Coast and the Gulf Coast. That's something that even Republican supporters in Florida are likely to oppose.

CURWOOD: In fact, didn't former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s promise Rick Scott, who was then Governor, he’s now a senator, that Florida would remain untouched for offshore oil drilling?

DYKSTRA: He did and that may have helped Rick Scott get elected to the Senate in a very, very tight race. But if you go back even farther, George W. Bush as President said he considered opening up oil leases off Florida, and he was opposed by his own brother Jeb Bush, then the governor of Florida.

CURWOOD: It looks like a family fight among the Republicans, huh? Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, we're gonna have to look in coming weeks for one of the stealthiest attacks on environment from the Trump administration; it involves NEPA. Maybe you've never heard of NEPA, and if you haven't, you're not alone. It's the National Environmental Policy Act. It's been around for almost 50 years. And it's the law that requires an environmental impact statement for things like dams, pipelines, levees, any big federal government backed project.

CURWOOD: And it can take quite a while to do those statements; in fact, that's what kind of hung up the Keystone XL Pipeline.

DYKSTRA: That's correct. And it takes up to three to five years to put an EIS together, an environmental impact statement. The law also allows for public input on such projects. It was also the thing that created the President's Council on Environmental Quality, the main environmental advisors for the White House. President Trump says he wants to streamline the process. He's already waived NEPA and some other laws in order to push through his border wall.

CURWOOD: Ok, let’s go back in history now Peter. What do you see?

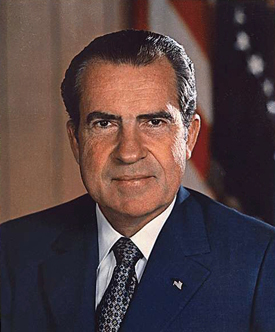

President Richard Nixon endorsed sustainability throughout much of U.S. policy during his time in office. (Photo: Central Intelligence Agency, Flickr, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: A 25th anniversary. April 22nd, 1994 -- April 22nd, of course, being Earth Day. 25 years ago on Earth Day, Richard Nixon died. Nixon created the EPA, he created NOAA, he signed the Clean Air Act. He actually vetoed the Clean Water Act, but then Congress overrode his veto. He created the Endangered Species Act and he also created the aforementioned National Environmental Policy Act. Richard Nixon died 25 years ago.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Independent | “Norway Refuses to Drill for Billions of Barrels of Oil in Arctic, Leaving ‘Whole Industry Surprised and Disappointed’ ”

- Environmental Health News | “Peter Dykstra: President’s Trump’s stealthiest environmental attack may be his biggest”

- Politico | “The Confidential Oil Plan that Could Cost Trump Reelection”

[MUSIC: Chris Belleau, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” on Swamp Fever, by Charles Mingus (Chris Belleau/Proud Dog Records)]

CURWOOD: Coming up – reflecting on the state of the planet in this time of Earth Day.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chris Belleau, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” on Swamp Fever, by Charles Mingus (Chris Belleau/Proud Dog Records)]

Earth Day Checkup

Earthrise is the image of planet Earth taken from the Apollo spacecraft during the first manned mission to the moon, led by NASA in 1968. This event has continuously sparked interest in the beauty of the earth, and the possibilities brought forth by science. (Photo: NASA, www.earthday.org, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Every April 22 since 1970 we celebrate Earth Day. And since that first Earth Day the water in the US is cleaner, and local air less polluted, but carbon pollution of the entire atmosphere of the planet has gotten worse and is changing our climate. The leadership that the U.S. government once showed on the climate crisis has almost vanished as President Trump vows to pull this country out of the landmark Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. Other big emitters like China and India are making big progress on renewable energy deployment, but face a difficult transition away from dependence on carbon heavy coal. To talk about these global responses to the climate challenge, we turn now to Jonathan Pershing, who led the US delegation to the UN climate negotiations during the Obama Administration. Jonathan is currently the Program Director of Environment at the Hewlett Foundation. Welcome to Living on Earth!

PERSHING: Great, thanks very much for having me.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Pershing, what is it costing the United States in terms of moral leadership to have backed away from the Paris Climate Agreement at this point?

PERSHING: I think it’s immense. The world is very, very clear about its own collective recognition of the severity of the problem. The United States actually turns out to have impacts that are significant, but they are dwarfed by the impacts that are faced by others. Just a few examples of places that people think about in the, in the news these days: we're having whole conversations around places like Bangladesh, where 10 million people are likely to be flooded out with only one foot of sea level rise. Where do they go? This is a very poor country, in a region that is currently quite volatile. Do they move into India? And what will India do with 10 million Bangladeshis moving in? Or take a look at what's going on now in Latin America. Latin America, clearly suffering in a number of different ways from a change in the climate today. Those are things that lead to a change in agricultural productivity, those in turn to a loss in jobs, those in turn to an increase in out migration from populations where there's nothing left at home. And where are they coming? Some are coming here. And we have those problems already today, already as a consequence, in part, of climate change; it's going to get worse. This is a part of the world in which 25% or more lives off of agriculture, and those damages are real. And those countries look at the US and say, You are one of the reasons we are being forced to leave. You, with your ways of significant emissions; if you curtailed, we'd have a much more promising future. Why can't you, why aren't you leading? We rely on you as a major partner in the global community, as a leader, to do just that. And when you back away, that has moral consequences, it has diplomatic consequences, it has consequences in terms of how people perceive us, not only in this arena, but in much wider arrays of climate and foreign policy.

Local air pollution in China has made coal power-related emissions related to climate change a key concern of its policies. China is now the leading investor on the world’s clean energy systems. (Photo: Leniners, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about, briefly, what the rest of the world is doing at this moment to deal with the climate emergency. Perhaps you want to start with China.

PERSHING: So I think countries have each chosen a somewhat different path. And that's to be expected. Each country will have its own circumstances, each country has its own opportunities. And so each country is choosing slightly different things to prioritize. Some, and the US is certainly one, is a diverse economy, with enormous landmass, with needs and change required in different parts of our country that would vary. You wouldn't expect Denver to do what you'd see in Detroit. These kinds of dynamics play out. And in a country as big as China, as another example, the same kinds of diversity holds. China's taking this quite seriously. In many ways, the government is run by a group of people who see the science as not only credible, but as urgent, who see impacts around their nation as being both immediate and far reaching, who have designs on the future, both in terms of the technology development, and in terms of protecting the nation against some of the worst impacts of climate, as being consistent with their vision of the future. What does that look like? Well, at one end, China's decided to go all-in on electric vehicles. So it turns out that transportation, and the heaviest part of that is cars and trucks, are responsible for about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. And we think that one of the futures for that sector is electric vehicles. China is leading in that regard, not just light-duty cars, but also things like buses. There's a city called Shenzhen, it is a city that has about 17,000 buses. Compare for a moment that to New York City. New York City only has 9000. Nearly twice as many buses in Shenzhen as in New York. They have electrified all 17,000 of those buses in the last three years.

CURWOOD: China has passed the United States in terms of absolute emissions, but not at all in per capita emissions. How are the Chinese doing, moving to the low or no-carbon economy, both in terms of the technology that they've deployed and the financial position that they have themselves in, compared to the US.

PERSHING: China has been the single largest reason for global growth in renewables, more renewables installed there than any other country in the world. But at the same time, for much of that period, Chinese demand has been growing. So instead of retiring one and replacing it with clean -- retiring coal and replacing it with solar -- you've added solar, you've added wind to the existing mix. The United States has been doing some of the same things, reducing a little bit, but mostly it's been about adding. In our case, we've added it, and what's replaced coal has been natural gas. That still has carbon emissions. So in that sense, our collective emissions have not declined as much as we thought. We went through a period of about a decade where U.S. emissions were slightly down; in the last couple of years, they've been inching back up. And that's a very, very daunting prospect as we look at the rate of change that is still required to solve the climate problem. China's in a similar place. This last year, Chinese emissions also went up, about the same percentage as ours did, actually; we're not all that different. But again, there, we represent the two largest greenhouse gas emitters in the world. And unless both of us can figure out how to change our trends, the world has only a slim chance of meeting our goals.

The city of Shenzhen, China, has the largest concentration of electric buses in the world. The transition to electric has helped reduce both smog and noise pollution. (Photo: Hans Johnson, Flickr, CC-BY ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way, what role is India playing? At the Paris gathering, Prime Minister Modi, who may or may not be reelected, pledged a trillion dollar fund to solarize much of the developing world and that they would get out of the coal business and move forward with renewable energies.

PERSHING: So I think it's a very -- at this instant, during the course of the election, it's a little hard to say what India is going to do next. I had the good fortune of being there just a few weeks ago, and had a set of conversations with a variety of officials in the government. And the sense that I took away from those meetings is that under the Modi administration, or even were he not to win, under a new administration, there is a commitment to this issue. That includes a commitment because of air quality, and that's largely driven by coal pollution, to really cutting back on their coal use. That's a commitment to being competitive in the global marketplace, including vis-a-vis China, and that means having the capacity to build their own renewables, including for export. That means a distributed generation question; they say that there's almost 400 million people in India who don't have access to electricity, and they're not going to run power lines to everybody, but they could put a solar panel on the roof. But they're seeing a demand requirement there. They're seeing the need that people have as they try to electrify the economy, so a great deal of what India has done has been additive. We're not really seeing retirements of coal. And as a consequence, Indian emissions have not gone down. They're going up. On a per capita basis, that's appropriate. Indian emissions are about one seventh the size of those of the United States. But can they become more efficient? Yes. Should they continue to be moving on the renewables? Yes, and they are. And will they need over the next 20 years to start retiring coal? Yes, they will, and that dynamic is going to be unfolding during the next presidency, whoever takes that office.

CURWOOD: What role does land use play in keeping carbon out of the atmosphere or even extracting it?

PERSHING: So land use is a huge share both of global emissions and of our future requirements to stop and to avoid the damages of climate change. The United States, on the end of the Obama administration term, we ended up doing an analysis to think about how we could get to an 80% reduction by the year 2050. And almost one third of that effort would have taken place in the US from land use and forestry. What does that mean? It means that you have to think about slowing and halting deforestation. It means that you have to think about some of the cover crops that you've got being modified to be more CO2 absorbent. It means that you think about how do you till the soil in such a way that you don't disturb the carbon and let it into the atmosphere, but you sequester it and hold it in those soils -- which by the way, makes them more productive, and makes them more useful for generating agricultural produce. And you'll also now have to think about adding forests, not just taking them away, or stopping taking them away; you actually have to add forest land, and those trees act like giant sponges in the atmosphere. And those are pretty good things; kind of, think about how Americans feel about their trees -- we love them. We like our parks, we like our wild spaces. We like our lands. And we like our parks if they're along rivers, and if they're in our cities. And if we add up that amount of wood and green space, can make a huge difference. Globally, same applies. Globally, we need to stop deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia. And globally, we have to manage the increase of our careful husbandry of agricultural lands and the increase of our forest lands.

CURWOOD: By the way, what about the rest of the world's financial needs? Less developed countries, some of them looking at the more immediate impacts of climate disruption, have less money to spend on both reducing emissions and adapting to this new world that we have. How well is the rest of the world doing in helping those places finance the new climate future?

PERSHING: I think this is a critical question, and one that has actually preoccupied negotiators the last decade and more. The question essentially, is, there are those who don't have resources, those who don't have the wherewithal to make these transitions. And there's been a commitment made by the rest of the world to provide assistance and support for them. It takes in my mind two completely different tracks, both of which are relevant to government policy, but are achieved in different ways. The first track is a direct transfer: support for development assistance, things that you do for the least developed countries, countries in Central Africa that don't have wherewithal. Countries in Central America that really are blocked, because there is no capacity. For those countries, you need technical assistance, you need some revenues, you need to provide aid in a direct fashion. But there's a separate set of countries, countries that have a middle class and a middle income community, countries where what you really want to do is invest. And that investment actually plays to the benefit of both those making the investment and those receiving it. That gives us a stake in the development of advanced countries in Africa. Ghana is a great example of a country moving very quickly down this path. We're seeing real work in Thailand and in Vietnam, moving down these paths. We're seeing big opportunities in places like Mexico, and in Peru, and in Chile, countries that actually will be recipients of major investment, and return to the credit of both the investor and the recipient. And we're competing in that market. China's making similar investments, Europe is making similar investments. It's up to us collectively to think about how we can win, because we're gonna be competing with others' resources for a future of our own trade export opportunities.

CURWOOD: How much money are we talking about to change our planet into a net zero carbon economy? What's the size of this?

PERSHING: So the size is actually probably measured in the trillions of dollars, it's a really remarkably large number. But I would be careful about using the number in the abstract; it sounds huge, except when you realize that no matter what we do, no matter how we think about our future, we'll still be spending trillions of dollars. So the relative difference between a world in which you have this very substantial changing climate, and a world in which the climate doesn't change anywhere near as much, that maybe is a 4% difference, 5% difference at most. And in fact, it may be offset by damages that you don't see. And those themselves would cost trillions of dollars. So in some sense, while the number is very large, the relative scale is relatively modest, and the damages avoided probably make the difference between a future that's quite bleak, and a future that's quite promising.

CURWOOD: Jonathan, before you go -- next year's the 50th anniversary of Earth Day; what would you like to see at that moment?

Jonathan Pershing was Special Envoy for the Climate during the Obama Administration and is now Program Director for Environment at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. (Photo: William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Public Domain)

PERSHING: You know, so, Earth Day is a remarkable thing. It brought to the table for the first time, this commitment at a global level, to the environment, to where we live. I think to a certain extent, prior to that, there had been a sense that you could continue to abuse the environment and it would keep on doing its thing, keep on being successful, absorb whatever punishment you gave it, and keep on ticking. And I think that was the beginning of a much deeper awareness about the fragility of some of these systems. Things are, in fact, in balance, and small changes can perturb that balance and lead to real consequences in the way we live our lives. Tim Wirth, who I worked for at the State Department in the early 1990s, had a very interesting phrase. He said "the economy is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the environment". If you in fact turn in the environment around, don't think the economy will keep on doing its thing. These are the things that Earth Day brought us. And now 50 years later, where are we? I think we've made some huge progress in some places around local pollutants. We've cleaned up a great deal of the US waterways; we've got much better air than we had back then -- although it's getting worse again; we're much better on things like mercury. But some of the other big problems? Not looking too good. The climate change problem, the bio diversity problem where we're seeing a loss of species; those problems are very big. And at this Earth Day, I would like us to recommit ourselves, not only to the local things we've begun to tackle, but to the big new global issues that we must also tackle if we're to have a life we'd like for our children and our grandchildren.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Pershing led international negotiations on the climate for the Obama administration, and now directs the Environment Program at the Hewlett Foundation. Jonathan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PERSHING: It's been a great pleasure to be with you.

Related links:

- William and Flora Hewlett Foundation | “Jonathan Pershing”

- Earth Day | “Earth Day 2019 - Protect our Species”

- Scientific American | “The Unfolding Tragedy of Climate Change in Bangladesh”

- Union of Concerned Scientists | “Renewable Energy”

- The Washington Post | “China’s Secret Weapon in the Electric Car Race”

- Earth Day Network | “Earth Day Network”

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on Spirit, by Paul Simon (Jazz Legacy)]

CURWOOD: Coming up- The City Nature Challenge, a bio-blitz to collect data about the wildlife in our neighborhoods.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on Spirit, by Paul Simon (Jazz Legacy)]

BirdNote®: What’s Your State Bird?

The Northern Cardinal is the most popular state bird, reigning in seven states total. (Photo: © Doug Greenberg)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Every state in the US has an official state bird. Typically, they’re native birds or have a strong connection to the state. But as BirdNote’s Mary Cann reports, that’s not always the case.

BirdNote®

What’s Your State Bird?

[Call of Ring-necked Pheasant]

MCCANN: This may sound strange, but a bird native to China is the official bird of South Dakota. It’s the Ring-necked Pheasant.

Most state birds are native, though — and common, except for Hawaii’s Nene (pronounced NAY-nay), a type of goose that’s endangered. [Nene call]

Some have special stories. In 1848, insects were devastating crops in Utah. A flock of California Gulls descended and devoured the pests, saving the Mormons’ first harvest. [California Gull calling in the background] A monument in Salt Lake City commemorates this avian intervention.

Utah’s state birds, California Gulls, are said to have saved Mormon farmers’ first harvest in the state when they wiped out crop-threatening insects. Salt Lake City commemorates these gulls with a monument. (Photo: © Terence Faircloth)

The “Blue Hen Chicken” is the state bird of Delaware.

[Clucking of Gallus gallus behind narration]

A captain in one of the first battalions from Delaware in the Revolutionary War raised Blue Hen Chickens for sport. Those soldiers — and those chickens — were famous for their fierce fighting. The company became known as "Blue Hen's Chickens,” still a source of state pride.

The Rhode Island Red’s place as state bird is a bit more mundane. The “Red,” a hardy and productive chicken, was nominated by the poultry industry.

The Northern Cardinal reigns in seven states — the most! [Northern Cardinal song].

The Western Meadowlark was picked by six [Western Meadowlark song].

And the noisy Northern Mockingbird by five. [Northern Mockingbird through end]

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Ellen Blackstone

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Ring-necked Pheasant and Nene recorded by G.F. Budney. California Gull recorded by R.C. Stein. Chicken recorded by W.W.H. Gunn. Northern Cardinal recorded by G.A. Keller. Western Meadowlark Gull recorded by W.R. Fish. Northern Mockingbird recorded by W.L. Hershberger.

Producer: John Kessler

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org April 2014/2016 March 2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

https://www.birdnote.org/show/whats-your-state-bird

CURWOOD: For pictures, fly on over to our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more on the BirdNote website

- State Symbols USA | “State Birds”

- 50States.com | “Official US State Birds”

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick and Friends, ”Orbit,” released as a single on www.joshuamessick.com]

Prepping for the City Nature Challenge

The first observation made on the trip to Thompson Island was made by Marc Albert of the National Park Service. The exciting find was coyote scat, but that didn’t stop the girls from getting up close to photograph it for iNaturalist. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

CURWOOD: Starting April 26th, thousands of people in hundreds of cities around the world will be participating in the City Nature Challenge, organized by the California Academy of Sciences. The event is what’s known as a bioblitz - a brief, intensive survey of biodiversity over a set area and time. Participants use their mobile devices to photograph the nature in their neighborhoods. The photos are then uploaded to an app called iNaturalist, where experts help identify every observation made. The data collected is available to any scientist for research. To practice their observational skills before the challenge, the Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls took some girls aged 12 to 15 to Thompson Island in Boston Harbor where they found some surprising evidence of local animals.

VOICE #1: Poop. Coyote poop.

VOICE #2: Scat. Look at that scat, guys.

VOICE #1: Do you all see that?

VOICE #3: Someone should photograph that!

VOICE #2: Who’s going to iNat that?

VOICE #4: Do you want me to take a picture?

VOICE #5: Yeah, take a picture.

VOICE #2: Alright, so remember with iNaturalist, we not only can document things that are

alive, we can document things that are dead, and we can document evidence of species. And so, taking a picture of this scat is a great thing to add.

VOICE #3: And I know this is poop, but it’s mostly hair of animals, so I’m going to touch it with the sticks. I’m just trying to show that there’s bones in here, which’ll make it clear that it’s probably not a dog.

VOICE #6: Coyote?

VOICE #4: Bone in the poopy?

VOICE #3: Bone in the poopy! And look at the photo she was able to take using the

magnifying lens.

VOICE #5: Bone in the poopy?

VOICE #4: Bone in the poopy.

VOICE #5: Whoa, there’s a bone in the poopy.

VOICE #7: So you have coyotes on the island?

VOICE #1: We do.

VOICE #7: That’s so interesting!

VOICE #1: They appeared here just a few years ago, just a male and female adult that came over, so we have a land bridge that opens up at low tide. So they made their way over, and then they had pups, so they had pups here. And so now we have a family, a grown-up family, that lives somewhere around here. They stay pretty much to themselves.

CUROOD: The City Nature Challenge will take place around the world from April 26 to 29 and it’s not too late to get involved. Anyone with a smartphone has the needed equipment, and you can find out how to participate on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- The City Nature Challenge

- The iNaturalist website

- Learn more about the Bostion BioBlitz Initiative for Girls

- Thompson Island Outward Bound Education Center

- Special thanks to the Boston Area City Nature Challenge Steering Committee

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co.]

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Aniakchak’s renowned caldera is a beautiful reminder of Alaska’s location within the Ring of Fire. (Photo: Courtesy Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: For much of the northern hemisphere, spring is finally in the air, and that has many of us thinking about summer travel plans. To help, we’ll be bringing you an occasional series in the coming months that explores the vacation possibilities in US public lands. A few weeks back we had a story about the Everglades National Park in Florida, and now we travel more than 5000 miles north to Alaska, and the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. This spot on the Alaska peninsula it is one of the least visited of our public lands and touts the catchphrase, “No lines, no waiting”. And it’s for the most adventurous among us as there are no roads to access the preserve. You must arrive by plane or by foot. But Outside Magazine contributing writer, Chris Solomon, says that’s part of the charm. Chris, welcome to Living on Earth!

SOLOMON: Oh, thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: What made you decide to go to one of the least visited places in the national park system?

SOLOMON: I really like to go as far off the map as possible. I mean, I've joked that my cell phone is a, is a bit like a reverse Geiger counter. As the cell phone bars of coverage drop, the possibility of adventure and a good time seems to increase. Everybody talks about the most popular national parks, and those places are great. But I wondered, what's the least popular place? And I wondered, is there something interesting about that place? Or maybe, why is it so unpopular? There was a list on the National Park Service website of the places that got the fewest visitors. And year after year, Aniakchak anchors the bottom of the list or is very close to the bottom.

CURWOOD: So, remind me, where in Alaska is Aniakchak actually located?

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve resides on Alaska’s peninsula, which leads into the Aleutian Islands. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: It's 350 to 450 miles, I forget exactly, southwest of Anchorage on this stub of a peninsula called the Alaska Peninsula that's warted with these quiescent volcanoes. It's where Katmai National Park is that people have probably heard of. Lake Clark National Park is in the area, these better known national parks. And then after the peninsula runs out, the Aleutian chain begins with people are probably more familiar with at least from a map. But, Aniakchak is on that peninsula as well. But, it's so little known that even as we sat in the airport, there was a big mural on the wall and these other national parks were on there and Aniakchak wasn't even on the mural in the airport as we headed there.

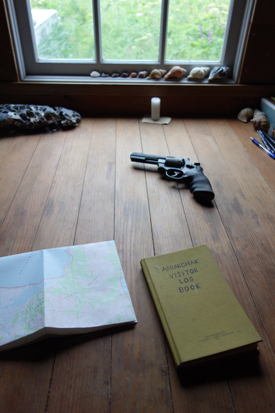

CURWOOD: What kind of company did you have with you, both two-legged and four-legged?

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so it was just three of us. There was a great photographer named Gabe Rogel, who's now a good friend. And our guide was Dan Oberlats who is the founder and chief guide of Alaska Alpine Adventures. So, it was just us three, along with a 44 Magnum called Pepe that was Dan's, to try and keep the bears at bay, because the Alaska Peninsula is, is known for some of the heaviest concentrations of the largest brown bears on Earth. They're relatives of the Kodiak brown bears, which are often said to be the largest bears, but the Alaska Peninsula bears are basically the same bears. One census found 400 brown bears per 600 miles, which is just astounding. I mean, there's something like 700 bears in 60,000 square miles of the Yellowstone ecosystem.

Chris’s guide carried a gun named Pepe to defend against grizzly bears. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Oh, my! So there you are, you head to Alaska, to Aniakchak, but I guess you just don't rent a car in Anchorage or something and start driving.

SOLOMON: No, you don't. So, you have to fly to, for instance, King Salmon, which is one of the bases of the Bristol Bay Salmon Fleet, and then maybe try to get to Port Heiden, which is a little dot of a town. And then, from there, you could either potentially fly a float plane into the monument, or in our case, the weather's so bad and unpredictable that we just decided to hoof it from Port Heiden. And we hiked about 22 miles up into the centerpiece of Aniakchak, which is this spectacular caldera.

CURWOOD: What exactly is the caldera?

SOLOMON: Yeah, so a caldera is essentially a volcano that has blown up, and then collapsed on itself and leaves a big bathtub. Essentially an empty ring, maybe the one readers would know best is Crater Lake in Oregon. And so Aniakchak has this great history and, it was so fun to discover this stuff, Steve. About 7000 years ago, as the Egyptians were kind of doing their thing and really dominating the Mediterranean area, this several thousand foot volcano, Aniakchak would have been, blew its top with the force of something like 10,000 atomic bombs. And then it, having done that, it collapsed upon itself. And over the course of a couple thousand years, it filled with several thousand feet of water. So it was this bathtub, and then one of the sides burst out with this tremendous flood. So then it became this empty ring with a hole in one side. And one of the great discoveries of doing this story is, you know, the native peoples, of course, knew about this place. But then in the early 20th century, this incredibly charismatic guy named Father Joseph Hubbard, who was called the “glacier priest”, came and quote-unquote, rediscovered it. And the glacier priest was this swashbuckling Jesuit from Santa Clara University, he would go on these expeditions around, around Alaska, often with a bunch of football players from Santa Clara University with their leather helmets on and they went to Aniakchak and they explored it. And they had found this place that hadn't blown up again in a couple thousand years. And inside were all these orchids growing in the warm soil, and they had bunnies that hadn't seen man. And so they would just walk right up to the football players who, who then ate them for dinner. And he described this sort of paradise found. And he wrote about this for, you know, places like National Geographic, and then he went away, and that year, it blew up again, and he came back and he described this kind of Dantean Inferno, and the place almost killed them with all the sulphurous gases. And so he wrote about it again, and became even more famous. So the glacier priest was one of the great finds of this story, and I was able to kind of follow some of his tales and writings as we explored the place.

At the bottom of Aniakchak’s caldera is Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: So take me back to a memorable moment or two for you in Aniakchak National Monument.

SOLOMON: We drop into the caldera after just being completely in the mist, you know, not knowing what we're going to find. And we drop into the caldera the second day, and we see this amazing place, and we camp by this beautiful little lake that's still the remnant of the bathtub that had been filled. And it's this lake called Surprise Lake where salmon still swim up into it and spawn, and they apparently taste like minerals from all the volcanic stuff that's still in the lake. And the next day we crawl out and we get on to the rim and you can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this, you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of you know of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it and it's just -- I still have the, the picture as my screensaver on my computer because I never tire of it.

Orange lava flows and hot springs speckle the bottom of the caldera, bleeding into Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: Is there another memory you have from there that you would like to share that’s sort of incredible?

SOLOMON: You know, one of the -- [LAUGHS] this might not be the kind of experience everyone wants, but we rounded a curve in a bay as we were exiting the monument. And around the corner, maybe a couple hundred yards away, was a, was a brown bear who was snuffling around, maybe he was on a kill, we couldn't tell. And he headed up on to the bluff where there was a lot of alders and underbrush and we couldn't see him anymore. That's not great because you want to keep an eye on the bear. So we decided to cut the corner across the bay and just walk through the tide flat and keep our distance. So we took off our shoes and started walking across the tide flat and the tide flat turned out to be almost thigh deep with tidal mud. So now we're reduced to walking at about one step every four or five seconds, as the mud is just sucking at our bodies. Meanwhile, we can hear the bear 150 yards away chuffing, you know, making unhappy noises in the underbrush. And then we get to the other side of the, of the bay. And the guide encourages us to walk as fast as possible. And I notice that he has drawn Pepe, the 44 Magnum, which encourages you to walk even faster. And we get to the other side of the brush. And we have no idea where the bear is. And there's a small path through the woods that we have to take. There's no alternative. And it turns out that it's what's called a bear trail. And these bear trails are these habitual paths that bears use for years, sometimes a century, sometimes longer. They're just, they're bear highways. And it was so well used by bears, by these thousand-pound bears, that the bear trail was knee deep with use. It was so worn. So we're walking through this incredibly dense thicket. We can't see 10 feet in front of us, with gun drawn, screaming and yelling 'hey bear!' 'Hey, bear!' with no idea where the bear is. And then we pop out on the other side safe. And we inflate our little rafts, and we float across a bay. And there's whales diving and puffins flying, and it was just a great end after a lot of adrenaline. So, [LAUGHS] It's the kind of thing that, you know, makes the colors a little brighter in life.

Brown bears are highly abundant within Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: How worth it was it to go?

SOLOMON: For someone like me who values wilderness, and solitude, and adventure, and who is willing to endure a little bit of discomfort and sogginess and freeze dried food [LAUGHS] for that payoff. It was a memory of a lifetime. And if you too are of that bent, I would encourage it highly. In 10 days, we saw two other people and they were fishermen who had simply pulled up on shore to just poke around for a few minutes. Otherwise we saw, we saw more bears than people; we saw beauty that I still tell people about. I made some friends for the rest of my life. I do find, and as I've written elsewhere, that the few people you go out with on these kind of experiences, these kind of wilderness experiences, have a way of really sharpening the relationships among the people that one spends time with. In short, it was one of better experiences of my life.

CURWOOD: Chris Solomon is a contributing writer for The New York Times and Outside Magazine. Chris, thanks so much for joining us today.

SOLOMON: Oh, it's my pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: And, I'm glad the bears didn't get ya.

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] So am I!

Chris Solomon is the Society of American Travel Writers 2018 Travel Writer of the Year. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

Related links:

- Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

- Outside | “Baked Alaska: Surviving Aniakchak National Monument”

- Chris Solomon’s Website

[MUSIC: Ray Charles, "America The Beautiful" on Ray Charles Forever, Concord Music Group]

[BEAR ROAR]

CURWOOD: We don’t have audio of the Aniakchak bears, but thanks to the National Park Service we do have a recording of grizzly bears in Yellowstone National Park.

[BEAR GROWL]

CURWOOD: Huffing and low growls indicate the bear is agitated or nervous.

Now, if you run into a grizzly, the Park Service has some advice: Don’t run.

Back away slowly and give the big bear lots of space.

[BEAR ROAR]

CURWOOD: That’s good advice, as a hungry grizzly can easily snap the bones of a one ton bison.

[BEAR HUFFING]

[MUSIC: Lawrence Blatt, “Here We Go” on Out of the Woodwork (LMB Music)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth