April 26, 2019

Air Date: April 26, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Klobuchar Goes Green

View the page for this story

Minnesota Democratic Senator and Presidential hopeful Amy Klobuchar is campaigning for action on climate change. At a recent “youth-focused” CNN Town Hall, Senator Klobuchar explained she can engage rural America as climate change is taking a huge toll on the middle of the country as well as the coasts, and why she supports the Green New Deal. (03:17)

A Citizen Science BioBlitz

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

The City Nature Challenge is an international contest known as a bioblitz: a brief, intensive survey of biological diversity over a set area and time. With a handy smartphone app, anyone can participate between April 26 and 29 by cataloguing the nature in their neighborhoods. Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill met up with the Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls during a trip to Thompson Island in Boston Harbor, where a group of teens practiced their observational skills for the competition. (07:04)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discussed a recent rash of beehive theft, which may be happening in part because of the continued decline in bee populations. Also, the upgrades to New Orleans levees in the wake of Hurricane Katrina at a cost of $14 billion for taxpayers may not be up to the task in just four more years. And in the history vault, the two look back 44 years to the publishing of an infamous Newsweek story on global cooling, still used to this day by climate deniers seeking to sow confusion about the science. (03:53)

Microbeads in the Great Lakes

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

Microbeads are tiny plastic spheres found in facial scrubs and other cosmetics, but sewage treatment doesn't remove them from the water, so they end up in lakes and streams. As Kara Holsopple of the Allegheny Front reported in 2104, they are a hazard to fish and to anyone who might eat lake-caught fish. (04:35)

Microplastics Leading to Macro-Problems

View the page for this story

Updating Kara Holsopple’s 2014 report in 2019, microbeads in cosmetics are now illegal in the US but overall, microplastic pollution is a growing threat to freshwater and saltwater ecosystems. Andrea Thompson, an associate editor of sustainability with the Scientific American, joined Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the microplastics crisis is harming people and nature, and possible solutions. (10:34)

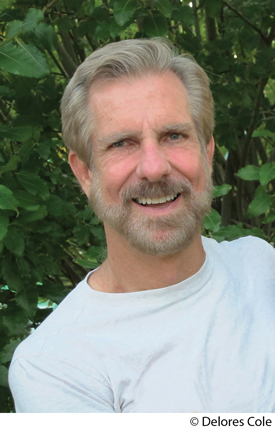

A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration

View the page for this story

Every spring and fall, a journey of thousands of miles begins, as migrating birds find their way between breeding and overwintering grounds. It’s an amazing phenomenon that naturalist Kenn Kaufman brings to life in his new book, A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Kaufman is the author of the Kaufman Field Guide series and is also a contributing field editor with the Audubon Society. He joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his latest book and what our species can do to avoid harming birds on their remarkable journeys. (16:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kenn Kaufman, Andrea Thompson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Kara Holsopple, Aynsley O’Neill

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Minnesota Democratic Senator and presidential hopeful Amy Klobuchar is campaigning for the Green New Deal.

KLOBUCHAR: Climate change isn’t happening a hundred years from now, it’s happening right now. And that’s why, as your president, on day one, I would get us back into the international climate change agreement. All right? That’s day one.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Also, microplastics are everywhere, and the magic of spring bird migration is in full swing, and the fall is even bigger.

KAUFMAN: Just leave a warbler, just drop it off in the north woods and it will find its way from northern Alberta, perhaps, down to Brazil, without any guidance. Without anyone showing it where to go. It’s amazing that they’ve got this instinct.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Klobuchar Goes Green

Amy Klobuchar is a U.S. Senator from Minnesota running as a Democrat in the 2020 Presidential Elections. (Photo: U.S. Senate, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

With the race for the Democratic presidential nomination already well underway, we’re keeping a close eye on what’s being said about climate change. On April 22nd, Earth Day, Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar spoke at a “youth-focused” CNN Town Hall. It was organized by the Institute of Politics, the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and the New Hampshire Institute of Politics. And sure enough, one of the 500 young voters in the audience at St. Anselm College in New Hampshire asked her about climate change. Senator Klobuchar supports the Green New Deal, and one student wanted to know how she was going to get buy-in for the Green New Deal from rural voters.

KLOBUCHAR: I think what's important, as you look at the goals in the Green New Deal -- and no one thinks we're going to dot every i and cross every t in a short period of time -- but we need those goals. We need as a nation to come behind goals, we need the energy of young people and people that really want to move on climate change. So this is what I say to my rural voters, I say, look at what's in front of you. Because for too long, we've been talking about it, I think, of more of a coastal issue -- which is true, rising sea levels; you just saw the Greenland ice sheet again was in the news today; hurricanes. But let's talk about it from the middle of the country where we need the political support. And I personally think someone from the heartland could do a pretty good job of that. What do we see in front of us? This is what we see: floods all over Iowa, Nebraska, and Missouri. This woman in Iowa, Fran, is literally standing with me with binoculars on, looking at her house which is submerged under water. And she says to me, this is where I live with my husband, and my two four year olds. And I said, well, is the river right there? Because it was looking... she says "no, the river's two and a half miles away. Ours is a house that's over a century old. There's still horsehair in the plaster. But this time for the first time, the water came in to my house." That's climate change.

Thanks for joining us for the #KlobucharTownHall! Now, take the next step and join the team >> https://t.co/iVg91M9DTq pic.twitter.com/bFEHnhD94b

— Amy Klobuchar (@amyklobuchar) April 22, 2019

Or you look at the wildfires in Colorado, or Arizona, or you think of that dad in Northern California, outside of Paradise, who's driving his little girl in the car with their house presumably burning behind them, and the flames are lapping over their car. And he's singing to her, singing to her, to calm her down. Climate change isn't happening 100 years from now. It's happening right now. And that's why as your President, on day one, I would get us back into the international climate change agreement.

[APPLAUSE]

All right? That's day one.

[CHEERS]

On day two -- on day two, and day three, I would bring back the Clean Power rules that the Obama administration worked out, that will make a big dent in it. [APPLAUSE] I would bring back, I would bring back the gas mileage standards that they just left and said, Oh, sorry, I know you car companies were ready to do it, but guess what you don't have to. That's what they did. And I would propose sweeping legislation for green buildings and new ideas. And we need to do this because guess what, it's you guys, not me. It's my daughter and you guys that are going to be inheriting this earth and that's why we need you on the front line. All right?

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Minnesota Democratic Senator Amy Klobuchar, speaking at a CNN Town Hall on April 22nd, 2019.

Related links:

- CNN Politics | “Takeaways from Amy Klobuchar’s CNN Town Hall”

- Amy Klobuchar’s Official Website

- United States Senator Amy Klobuchar | “Environment, Climate Change, Homegrown Energy and Natural Resources”

[MUSIC: Christian McBride Trio, “My Favorite Things” on Out Here, 2013 Mack Avenue Records II, LLC]

A Citizen Science BioBlitz

The first observation made on the trip to Thompson Island was made by Marc Albert of the National Park Service. The exciting find was coyote scat, but that didn’t stop the girls from getting up close to photograph it for iNaturalist. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

CURWOOD: Each spring brings the chance for city folks from all over the world to get outside and take part in the City Nature Challenge. It’s a bioblitz competition for people to document nature in their own communities. This year, an estimated 25,000 people, in over 150 cities, are expected to participate between April 26 and May 5. The team that collects the most data gets bragging rights for the year and all of the information collected is uploaded to a database and made available for scientific research. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill caught a ferry out to the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area with a group of teenage girls. They’re part of the Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls, and went to Thompson Island to practice their skills for the challenge.

[BOAT RUMBLE]

O’NEILL: It’s an overcast spring day, but our group of girls is still excited to be heading out to explore the island habitat. There are 10 of us onboard a small ferry boat, 5 teenagers from different Boston public schools, and their educators from Zoo New England, Brandeis University, and the National Park Service.

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: On the island the spring thaw and rain mean plenty of mud. Fortunately our guide for the day, Luke Thorson from Thompson Island Outward Bound, has planned ahead.

LUKE: We have some tools that we’re gonna give you that’s gonna help you explore today, help you feel comfortable going out, getting your feet… not wet, but your boots wet.

Luke Thorson from Thompson Island Outward Bound (left) Marc Albert from the National Park Service (center) help two of the BioBlitz teens out of a particularly sticky spot in the marsh. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

O’NEILL: This field site on Thompson Island is maintained by the program Outward Bound, and frequently hosts Boston public school students. Luke directs us to a shed where we change into knee-high waders.

LUKE: It is early in the season, so we’re gonna have to do some looking, and get down, and get dirty, and see where things are, meet them where they’re at.

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: Luke passes out some field guides and we hit the trail down to the salt marsh.

VOICE #1: What’d you catch?

VOICE #2: It was just a black bug that just, it hopped; it’s not that big.

O’NEILL: As we walk, we spot some bugs and some birds. And we’re hoping to see hermit crabs, oysters, fish maybe. But before we even get to the marsh the girls find something unexpected. Marc Albert from the Park Service, Colleen Hitchcock from Brandeis, and Luke help them identify it.

LUKE: Poop. Coyote poop.

COLLEEN: Scat. Look at that scat, guys.

LUKE: Do you all see that?

MARC: Someone should photograph that!

COLLEEN: Who’s going to iNat that?

VOICE #1: Do you want me to take a picture?

VOICE #2: Yeah, take a picture of it.

COLLEEN: Alright, so remember with iNaturalist, we not only can document things that are alive, we can document things that are dead, and we can document evidence of species. And so, taking a picture of this scat is a great thing to add.

O’NEILL: The girls take a picture and upload it to an online database using an app called iNaturalist where experts will identify whatever’s in the photo.

MARC: And I know this is poop, but it’s mostly hair of animals, so I’m going to touch it with the sticks. I’m just trying to show that there’s bones in here, which’ll make it clear that it’s probably not a dog.

VOICE #1: Coyote?

VOICE #2: Bone in the poopy?

MARC: Bone in the poopy! And look at the photo she was able to take using the magnifying lens.

VOICE #3: Bone in the poopy?

VOICE #2: Bone in the poopy.

VOICE #3: Whoa, there’s a bone in the poopy.

VOICE #4: So you have coyotes on the island?

LUKE: We do.

VOICE #4: That’s so interesting!

LUKE: They appeared here just a few years ago, just a male and female adult that came over, so we have a land bridge that opens up at low tide. So they made their way over, and then they had pups, so they had pups here. And so now we have a family, a grown-up family, that lives somewhere around here. They stay pretty much to themselves.

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: When we arrive at the marsh it’s a flurry of activity to get out nets and Petri dishes, and to grab the smartphones and tablets we’ll use to document the species. Within minutes the girls are sifting through water to find plankton, bugs, and perhaps the most hoped-for critter, hermit crabs.

VOICE #1: Oh, a hermit crab! Aah! Success!

Hermit crabs were one of the favorite finds of the girls. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

VOICE #2: He’s, like, hiding! Should we go do it on iNaturalist?

VOICE #1: Yes.

VOICE #3: We definitely have to iNat that. Yay!

VOICE #2: So cute!

VOICE #4: He’s, like, popping in and out.

VOICE #1: Nice job, Kendra. Okay. Let’s put a little tiny bit of water in there.

VOICE #3: Are you gonna hold it?

VOICE #5: Oh, I can hold it.

VOICE #1: Oh, does any of you want to hold it?

VOICE #3: Definitely should hold it.

VOICE #4: Really tiny!

VOICE #5: Let’s go see how many hermit crabs we can collect and see if we can find the biggest one.

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: When we wrap up at the marsh, the sun comes out and we head to the beach to look for native and invasive oysters.

MARC: So we want to go down as low as possible into the low tide area because oysters live underwater basically. They don’t want to be up here where it’s only covered during the high tides. But you can start to see oyster shells already. These are dead oysters, the shells wash up higher. But we ideally want to find some live oysters.

Within a small stretch of Thompson Island’s beach, 26 European Flat Oysters, invasive to the area, were documented. In contrast, in the same stretch of beach, only two native Eastern oysters were found. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: The oyster data that’s collected from the City Nature Challenge, will help researchers trying to determine the current ratio of native to invasive oysters in this region. The bioblitz team marks off an area and identifies as many oysters as they can find in that space.

VOICE #1: So, one, two, and then three, four, five, six, seven, seven and a half.

MARC: Actually, we found the other species!

VOICE #2: Oh!

MARC: So look at this! So if you open this up, see that purple thumbprint in there?

VOICE #1: Yeah.

MARC: That's an indicator that this is actually the native Eastern oyster.

VOICE #1: Wow, that’s cool!

MARC: And so they very strongly attach to rocks. So that's not surprising that we're seeing this one attached to rocks. But you see, you look inside these other ones, they don't have that same telltale sort of purple thumbprint.

VOICE #1: Wait, so these are the native ones?

MARC: These two are the native ones.

O’NEILL: Eventually, the team finds 26 of the invasive oysters, and just two of the native ones.

[FOOTSTEPS]

O’NEILL: As Thompson Island fades in the distance, I ask the girls what they’ve liked best.

VOICE #1: I think the salt marshes, because that’s when we saw the most life, and it was really fun, like with the boots, and like in the water, and finding all those hermit crabs and everything.

VOICE #2: Well, I also really liked the salt marshes, because we got to, like. I never really paid that close of attention to how much life there was. And I really liked just getting muddy and just exploring.

O’NEILL: And to document the life they’ve seen, the girls log on to iNaturalist. With heads down, huddled around our phones, we must look quite the sight – windswept, muddy, slightly sunburnt, and appreciating nature in our own new-fashioned way.

The Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls and their chaperones. (Photo: Courtesy of Colleen Hitchcock)

For Living on Earth, from Boston Harbor, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

[BOAT RUMBLE]

CURWOOD: Data collection for the City Nature Challenge happens April 26 through April 29, and between April 30 and May 5, naturalists will be identifying the observations. If you are a citizen scientist who would like to get involved, you can find out more on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The City Nature Challenge

- The iNaturalist website

- Learn more about the Boston BioBlitz Initiative for Girls

- Thompson Island Outward Bound Education Center

- Special thanks to the Boston Area City Nature Challenge Steering Committee

[MUSIC: DJ Sun, “Journey” on Qingxi, Soular Productions]

Beyond the Headlines

California’s agriculture is highly dependent on bee pollination, creating an opportunity for beehive bandits. (Photo: Justin Leonard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, at least the connection is up. Peter, are you there?

DYKSTRA: I'm here. How are you doing, Steve?

CURWOOD: Good. And tell us, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, this is a story that ran a little while back, chased down by Vice News. And it's about an environmentally-related crime that just hit me totally out of the blue. I didn't expect this. There's a rise in thefts of beehives.

CURWOOD: People are stealing bees?

DYKSTRA: People are stealing bees because bees are so essential to the pollination of a lot of crops. The biggest example would be the almond crop grown in this country almost entirely in California. The pollination season is February. The growers rent beehives from beekeepers all over the country. The hives go for as much as $350 each in rental and starting two years ago, there was a million bucks worth of beehives that just vanished. This year, the total might be higher.

CURWOOD: Huh. And who's stealing these?

DYKSTRA: They haven't figured out exactly who, but the suspects are other beekeepers. Obviously, they would have interest in having more bees, but also they would have the equipment, because if you're going to steal a beehive, you need the same equipment that you would need to keep a beehive and the only people who have that are beekeepers. So they are the persons of interest.

CURWOOD: And I imagine for the cops to catch these bee rustlers, they'll set up a sting.

DYKSTRA: Oh, you were just waiting for that one.

CURWOOD: Of course. Hey, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, New Orleans and the feds of the state of Louisiana spent $14 billion, mostly federal money, on upgrading New Orleans levees after Hurricane Katrina. But now the Army Corps of Engineers and some advocacy groups are saying that $14 billion is only going to last about four years of guaranteed protection for New Orleans.

The devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina led to the construction of levees to protect against flooding. Recent constructions are likely to need more work, due to the soft soil underneath and increasing sea level rise. (Photo: Ray Devlin, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wait a second, $14 billions to buy four years? That doesn't make a lot of sense.

DYKSTRA: Well, you've got two things going on. One is the natural process of land subsidence: when you have marshy land, like most of Louisiana, or like the islands in the Chesapeake Bay, they just tend to sink. And while they're sinking, sea levels are rising. The levees themselves are sinking a little bit with the land. And the Army Corps says the time is short before they're going to have to upgrade the levees again.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and one reason, by the way, that this land is sinking is that the Mississippi isn't allowed to make more land. It's getting channeled through there.

DYKSTRA: Oh, yeah. The Mississippi is chopped up. The oil and gas industry takes a lot of the blame for that. And people in Louisiana are scrambling to save their state.

CURWOOD: So let's take a look back in the history vaults.

DYKSTRA: Oh, this is one of my favorite ones. April 28, 1975. That's the day that Newsweek published its infamous "global cooling" story. It's been left in the dustbin of history except by climate deniers who use it to this day to sow doubt about climate science, which was back in its infancy then.

CURWOOD: And who wrote this story? And what was the basis for it?

DYKSTRA: Peter Gwynne was the science editor for Newsweek. He's a respected journalist, but we caught up with him a few years ago. He said a very journalist-like thing, he said he stands by the story based on the facts as we knew them, but he also acknowledges that science moved on very quickly from any theories about global cooling. Science moves on and advances and improves, the same way that the music industry does, which is why The Captain and Tennille aren't occupying the number one slot anymore.

The story “The Cooling World”, published by Newsweek in 1975, still acts as the banner for climate deniers to this day. The author wrote an article for Insider Science, explaining that climatology has changed, and that an old magazine article should not be used to deny current scientific data on climate change. (Photo: NASA Goddard, NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Of course, that was the hit music in April 28, 1975. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org. And DailyClimate.org. Hey, we'll talk to you again real soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Vice News | “Watch a Bee Theft Detective Bust a Hive Heist”

- Scientific American | “After a 14-Billion Upgrade, New Orleans’ Levees are Sinking”

- Inside Science | “My 1975 ‘Cooling World’ Story Doesn’t Make Scientists Wrong”

- Scientific American | “How the 'Global Cooling' Story Came to Be”

[Captain & Tennille, "Love Will Keep Us Together" on Love Will Keep Us Together, 1975 A&M Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Scientists have found microplastics everywhere from Arctic ice to human stools. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay Tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsfortheSea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Billy Childs Ensemble, “Scarborough Faire” on Lyric, traditional/arr.Billy Childs, Lunacy Music]

Microbeads in the Great Lakes

The majority of the plastic that Mason and her team found in the Great Lakes were tiny pieces called microplastics. (Photo: 5 Gyres)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In honor of Earth Month we are looking back at some of our favorite stories and bringing you an update. We commonly think of fossil fuels such as natural gas, oil, and coal, as having a long-term impact on the environment as they are burned and release the global warming gas carbon dioxide into the air. But those fossil fuels are also the principal feedstock for plastics, and these can persist in the environment for years as well. So today, we have a story from 2014 about plastic microbeads making their way into the Great Lakes. These tiny bits of plastic can be found in skin care products like facial scrubs and exfoliants, and are so small, water treatment plants don't remove them. Kara Holsopple from the public radio program The Allegheny Front had the story.

HOLSOPPLE: Salon owner Marla Degenhart is enjoying a hand massage with a creamy French vanilla scrub.

[SLATHERING SCRUB ON SKIN]

DEGENHART: That’s awesome. [LAUGHS] It feels great. Very scrubby, and it’s also a little more exfoliating than the oatmeal.

HOLSOPPLE: Degenhart makes the homemade scrubs herself for her Lunasea salon and spa in Pittsburgh.

DEGENHART: Everything that I use, every ingredient that I use is biodegradable. I’m very earth-conscious. I’ve been like a hippie my whole life. I don’t look like one, but I think like one. [LAUGHS]

HOLSOPPLE: Degenhart adds oatmeal, fine pumice, and even ground up walnut shells to her exfoliating masks and cleansers.

These natural skin care products are the kind that Dr. Sherri Mason says she’d like to see more of. She’s from the State University of New York at Fredonia. Mason’s been pulling an ingredient in the commercial version of cosmetic scrubs out of the Great Lakes by the thousands - microplastics.

MASON: About 60 percent of the microplastics we found were these perfectly round, spherical balls. And those definitely don’t come from the degradation of larger plastic items.

HOLSOPPLE: They come from face washes and cosmetics with small, colorful plastic beads - microbeads - that do the job of exfoliating skin. Mason and her team have been trawling the Great Lakes by boat for the last two summers, looking for plastic. Their work is the first study of plastics pollution within the Great Lakes, and one of the first on freshwater plastics pollution.

Half of the plastic in oceans are microplastics--pieces about 1 to 5 millimeters. In the Great Lakes, it’s 80 percent - most of it in Lake Erie.

Many of us think of plastic pollution as an eyesore--plastic cups and bottles floating near the beach. But little plastic pieces make their way into the Great Lakes first as those larger plastic items like bags or cups - trash that gets washed through storm drains. Then they get broken down by sun, wind, and water. In the case of microbeads, they come through municipal sewers. Mason says finding that so many of these microplastics were little beads was a surprise. And they could be creating big problems for wildlife.

MASON: They essentially look like fish eggs. They look like food. The biggest concern is the possible ingestion of these microplastics by aquatic organisms.

HOLSOPPLE: Mason says similar ocean studies show they are eaten by birds and fish--they’re so small even mussels and plankton - at the bottom of the food chain - can eat them. The plastics prevent wildlife from digesting real food, and that can kill them. But that’s not the only issue. Mason says the Great Lakes were once a dumping ground, and even though pollution is more regulated now, some chemicals are persistent. Plastics found during Mason’s study had elevated levels of industrial chemicals like PCBs. Michelle Naccarati-Chapkis with Women for a Healthy Environment explains why.

NACCARATI-CHAPKIS: Those dangerous chemicals can essentially bind to plastics.

HOLSOPPLE: Her Pittsburgh-based group’s been reaching out to other environmental groups in the Great Lakes region, asking them to put pressure on retailers to stop carrying products which contain hazardous chemicals. They’re worried about chemicals which can’t be removed through water treatment. Naccarati-Chapkis says it bioaccumulates; the fish eat these toxic-coated plastics and then we eat the fish.

NACCARATI-CHAPKIS: So we know that it works up the food chain and as a result will impact human health as well.

HOLSOPPLE: Naccarati-Chapkis, Sherri Mason and others say that eating fish from the Great Lakes - where commercial fishing is an important industry--could be dangerous because the toxins in the plastics the fish ingest could leach into their flesh that we eat as food.

CURWOOD: That 2014 report from Kara Holsopple came to us courtesy of the public radio program the Allegheny Front.

[MUSIC: The Roy Hargrove Quintet, “Strasbourg / St. Denis” on Earfood, 2008 Groovin’ High]

Microplastics Leading to Macro-Problems

Microplastics are being found all over the globe, including in areas relatively untouched by humans. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Back in 2015, Congress passed a law banning microbeads in personal care products that took effect in July of 2018. But it turns out plastic microbeads in cosmetics were only a small part of the problem. While we hear a lot about the large patches of plastics in the oceans, it is less well-known that scientists are also finding microscopic bits of plastic just about everywhere they’ve looked, including the human body. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Andrea Thompson, who wrote a three-part series about microplastics for the Scientific American.

THOMPSON: So there are both the sort of really tiny bits of plastic from things like bottles or bags that form as those bigger plastics degrade in the environment from exposure to water, or sunlight or being blown around by the wind. But there are also what are called microfibers, which are exactly what they sound like, fibers that slough off of our clothing and other fabrics that are already kind of micro-sized. And those cover not only a huge range of sizes, going from a few millimeters, to something we'd be able to see, down to things you have to have a microscope to see, as well as a whole bunch of different types of what are called polymers. So, the chemicals that make up plastic. And those are things like polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, which is you know, used in foam food containers. So it's, it's really a whole bunch of different things.

Microfibers make up a large component of microplastics and often come from fabrics. (Photo: GTM NERR, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And you write that there's also now something called nanoplastics, and these can be as small as the size of a virus. Can you tell me about that?

THOMPSON: Yeah, absolutely. So it's basically the same thing as microplastics, just on an even smaller scale. And those are something that scientists are really only beginning to grapple with. Because while we can detect them in laboratory tests, where we kind of know what we're looking for, the technology isn't really there to find them in the environment. Because the existing technology can't find things that small, we really don't have a good sense of how much of that is out in the environment. But given that, basically, the smaller the size you look at, the more number of particles you find. There's a good chance that there are quite a lot of them out there that we are only touching the tip of the iceberg with what we found so far.

BASCOMB: What is the scale of the problem of microplastics and nanoplastics in our environment? I mean, it is even a knowable answer.

THOMPSON: It is to a certain extent. So it's definitely a global problem. Basically, everywhere we've looked, we found them. You know, kind of started in the oceans, including particularly in what are called gyres. So basically, where ocean currents come together and swirl around and sort of collect junk. But we've started finding them in freshwater, there's been a lot of studies, including in the Great Lakes in the US, that have found them there in concentration similar to some of these garbage patches, these gyres. They've also been found in soil. So when, when you take wastewater, the sludge that's left over from cleaning wastewater, it's really rich in nutrients, and gets applied to agricultural fields as fertilizer. Unfortunately it seems to be rich in microfibers from the US washing our clothing. And so that actually gets applied as well. So we're definitely finding that in soil. But we've also found it as far away as the Arctic, on Arctic sea ice and within it, so if it's there, it's pretty much probably almost everywhere on the planet. So it's a really complex problem to try and figure out how much of this is out there, where it's coming from, and how it's moving around the environment. And that's what scientists are really grappling with now.

BASCOMB: That was my next question. I mean, I've read that they found, as you said, plastics, microplastics, everywhere that they've looked, from sediments at the very bottom of the ocean to isolated lakes in Mongolia. I mean, how are they getting there?

Plastic pollution is a major problem from the macro to micro scale. (Photo: Emilian Robert Vicol, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

THOMPSON: So we're still kind of working that out. You know, with the ocean, really it all originates from land, because that's where we live. And we're the only creatures that use plastic. In terms of the ocean, some of its washing from rivers, some of it might be coming from landfills, or things that are on coasts. Could be, you know, kind of just blowing off into the water. There is growing research to show that these microplastics are being carried around in the atmosphere. And that's one of the key ways they may reach some of these really remote places where there isn't a lot of human habitation to explain why there might be plastic. So that would tend to probably be stuff on the smaller range, and especially microfibers, because their shape just kind of naturally lends well to wafting in the air. You can see it if you're sitting and looking at a shaft of sunlight. And you notice the little things that particles of dust, some of that is probably microplastics and microfibers. Not all, and we don't know exactly the proportions yet. But those are some of the ways it's getting around as sort of following these natural air and ocean currents and rivers and things like that.

BASCOMB: A lot of us have probably seen these photographs of whales and fish with their guts just full of larger pieces of plastic. And they eventually kind of die of starvation since there's no room left over for food. But how did microplastics impact the health of marine animals that digest them.

THOMPSON: So we're still figuring that out a little bit. And they're a little different from these bigger plastics, because they are smaller in size. They have been found, in marine creatures is mostly where we've looked, but also some fresh water aquatic creatures. My belief, at least some laboratory experiments, things like earthworms can eat them too. So that brings it back to the terrestrial side. Some of the concerns for that are that they could rub against basically, you know, the gut lining, and cause irritation, inflammation that could lead to other health problems for these creatures. And if they're small enough, that they might actually get absorbed through the gut lining and get into the bloodstream, which has been shown that it can happen, we're not really sure how widespread that is. And the worries there are also that all of the other chemicals that are in these plastics, the things that get added to them, you know, either a coloration or what are called plasticizors, that make them more moldable, those could get introduced into animals this way, into the bloodstream if they're getting absorbed. So those could eventually maybe impact the reproductive ability of the species. And there has been some experimental evidence that shows that, at least in some species, introduced a certain types of microplastics that you do see, you know, declines and reproduction, and that that actually goes on to subsequent generations. So it's not just the fish that ingested the microplastics, but it's that fish’s children too.

BASCOMB: And what about people that eat fish that are full of microplastics, is that a concern?

THOMPSON: So it's a little bit of a concern, from what I've talked to from most people, because at least in fish, we haven't seen a lot of widespread evidence that it is, a lot of this micro plastic is getting outside of the gut into the wider tissue of the fish. So if most of it is getting trapped in the gut, we don't really eat the guts of fish. So most of it, we wouldn't be exposed to. Now, with shellfish like scallops and things, that's not the case, we might be exposed there. But it is clear that we are ingesting and likely inhaling microplastics from the air. There was another study actually, very recently, that looked at human stool samples and found pieces of microplastic in it. So that was some of the first direct evidence that we're definitely ingesting it. And then with inhalation, is enough of it small enough that it could penetrate deep into the lungs.

Microplastics have even been found in soil. (Photo: Surfrider Foundation Oregon Chapter, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So an obvious thing we need to do here is just produce less plastic to begin with. And a lot of cities are looking to do that either banning single use plastic grocery bags and straws, things like that. How far will that get us though, towards addressing this problem?

THOMPSON: Yeah, so pretty much everyone I've talked to who studies plastic pollution in general, but microplastics specifically too, has said, you know, bans are fine, but they're really only a starting point. They won't come as close to addressing the larger issue of the scale of the amount of plastic we produce. And they often don't target production directly, you know, so if one city bans them, the company that's making those bags might just shift their, you know, market to somewhere else. And that market may not have as good a waste system, as you know, a city in the US. So is that really the best way to do it? And there's also the consideration of what alternatives is that pushing people towards. If it just means we're doing more paper bags, or you know, everyone gets an organic cotton tote that comes with a lot of land use, fertilizer use, water use, you know, what is actually the best alternative. Another is that PET is one of the most recyclable, it's probably the only part of the plastic recycling system that is profitable, and really works really well. And that's the stuff that you know, water bottles and soft drink bottles are made of. The problem is, if you, say, introduce coloring to that, that makes that plastic less desirable to the recycler, it's harder for them to deal with. And that coloring isn't there for any food safety reason, it's a marketing thing. So we're taking one of the most recycled plastics and rendering it less valuable by adding coloring to it that isn't really necessary. So there are even little things like that that can make a big difference in terms of how much actually gets recycled.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor of sustainability with Scientific American. (Photo: Courtesy of Andrea Thompson)

BASCOMB: Now that we have an idea of the scope and the potential danger of this problem, I mean, what in the world can be done to clean up the microplastics that are already so ubiquitous in the environment?

THOMPSON: Most people that I talked to have said, at least in terms of addressing micro plastic pollution, the key is to stop stuff from getting into the environment, just to turn off the tap of things that are getting in there. Because right now, with any cleanup we can do, we can't clean it up as fast as it's going into the environment. So we'd be playing a constant game of catch up. So it's better to tackle the introduction and just stop new stuff from getting in there. And you know, that's going to take a dedicated look from lawmakers to figure out what are the things that are actually going to have kind of the most bang for our buck.

CURWOOD: Andrea Thompson is an associate editor of sustainability with the Scientific American. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Scientific American | “Earth Has a Hidden Plastic Problem—Scientists Are Hunting It Down”

- Scientific American | “Microplastics Are Blowing in the Wind”

- Scientific American | “Solving Microplastic Pollution Means Reducing, Recycling—and Fundamental Rethinking”

[MUSIC: Billy Childs Ensemble, “Scarborough Faire” on Lyric, traditional/arr.Billy Childs, Lunacy Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up - the trips of thousands of miles that begin with just a single flap of a wing. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Time For Three (featuring Branford Marsalis), “Queen Of Voodoo” on Time For Three, by R.Meyer & N.Kendall/arr.Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics]

A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration

Many songbirds are known to make their migration during the nighttime hours. (Photo: Unsplash, Barth Bailey, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Kenn Kaufman is a renowned writer, artist and naturalist who has produced a variety of books focusing on the natural world, including the eight-part Kaufman Field Guide series. Since the age of six, Kenn has been a self-proclaimed bird nerd. He joins us today from northwest Ohio to talk about his 2019 book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration. Thanks for being with us, Kenn!

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's great to talk with you.

CURWOOD: Your new book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." But you've written a bunch of them, how many guide books?

KAUFMAN: I've written about seven actual identification guides to nature. And, then a couple of books actually intended for reading.

CURWOOD: So we shouldn't read the guidebooks, huh?

KAUFMAN: Oh, well, a lot of people just look at the pictures!

CURWOOD: But, I bet little Kenn would have actually read it from cover to cover.

Kenn Kaufman’s new book A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration is available now. (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) I would have, yes. The guide books that I did have I did read cover to cover. I had memorized books by Roger Tory Peterson by the time I was 10 years old.

CURWOOD: What prompts, a kid really, to have practically memorized a field guide to the birds by Roger Tory Peterson.

KAUFMAN: Well, I was just so fascinated with birds as a little kid. I mean, I, I sort of discovered birds when I was about six. And, when you look at things like robins or grackles out on the lawn, and you get close to them, which you know, as a kid, you could just crawl across the lawn. Nobody thinks anything of it. Those birds are just so intense. They are so intensely alive, that I was just captivated by looking at them. And, so, I've just been utterly fascinated with birds and then with other aspects of nature, ever since I was six or seven years old.

CURWOOD: So, last time we spoke you were in Arizona, why are you in Ohio?

KAUFMAN: Well, I mean, Arizona is great for natural history in general. And there are a lot of birds there. But bird migration is not so obvious there as it is in eastern North America. There's just more birds that pass through the eastern half of the United States. And this area, Northwestern Ohio, the edge of Lake Erie, is really a fabulous concentration point for migratory birds.

CURWOOD: Well, how do you see them? Because as you write, the songbirds migrate principally at night.

Warblers are the most popular of the migratory songbirds that mark the peak of spring migration. The Blackburnian Warbler spends the winter in the Andes in South America, migrates north in spring through Central America, across the Gulf of Mexico, through the eastern U.S., heading for breeding grounds that are mostly in the spruce forests of Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: That's right! So, it's sort of this massive phenomenon that's largely invisible. And, that's that's part of what makes it interesting. But here, birds are coming north on a broad front across eastern North America, they come North across Ohio, they get close to the edge of Lake Erie, and if it's approaching dawn, they can see that there's water ahead. And these birds will just come down and then land and so the numbers pile up on the edge of Lake Erie, the little wood lights there. On a good morning, after a good night, those woods are just full of these small songbirds. They concentrate there, and often they'll stay for several days feeding and fattening up for the next flight.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a term that's often thrown around where birds go during migration called flyways. But you write that flyways are a dated concept, why?

KAUFMAN: It's an interesting concept. The idea of bird flyways was developed first by people who were studying duck migration. And it was easy to study duck migration, because you can catch a bunch of them at once at some water area and put bands on their legs and then later ask the hunting community to send in the duck bands from the ducks they've shot. You very quickly can get a sense of where a lot of these birds have gone. And ducks do sort of follow specific flyways from one water area to another. But the great majority of birds don't follow anything like that. If you could look down on North America from outer space on a night at the peak of migration to see where the birds were going, you wouldn't see rivers of birds flowing toward the north. It would look more like a blanket of birds being pulled northward.

CURWOOD: And, yet, you write that people often come at the spring migration time to where you live there in Northwest Ohio. So if it's not a flyway, why do people come from all over the world to watch the migratory birds in your neighborhood?

KAUFMAN: They come there, because of the sheer concentrations of birds. The birds are moving north on a broad front. So, there would be just as many individuals passing over an area, say 150 miles farther west. But in this area, they're pausing because they're coming up to the edge of Lake Erie. And, we also have a lot of really good habitat here. So, birders can spend all day, or spend all week, going from one wood lot to another, or going to the marshes, going to the fields. And every place they go, they'll see concentrations of these migratory birds that are stopping over.

CURWOOD: By the way, what about the fall migration?

In the summer the Eastern Kingbird live in the eastern two-thirds of the U.S. and southern Canada, feeding on insects in open country. In winter, they gather in flocks in the Amazon rainforest, feeding on small fruits in the treetops. Talk about a double life. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, fall migration is exciting. Actually, for the, the really serious birders they're often more excited about fall migration. There are more birds then. The total population is higher because the birds have been hatching young all summer. So you have all these young birds migrating south for the first time. So, the numbers are higher, and the young birds are more likely to wander out of range. So you'll get more rare birds, more things in places where they shouldn't be, during the fall. So, it's a very exciting time for birding. But to me, the thing about spring is that it's just a sense of resurrection, almost. A sense of rebirth. Especially if you're in northern Ohio, and things have been frozen solid all winter, and things start to thaw out. And all these birds come back. It's just such a, such a wonderful feeling that I can't help just wanting to go out and celebrate.

CURWOOD: Let's just say that one of the spring mornings, I'm with you there near the coast of Lake Erie. Springtime migration is happening. What does it sound like? What does it look like?

KAUFMAN: It's just a fabulous experience, if you can be out there at dawn or just before first light, along the edge of Lake Erie because you hear the night sounds, of course, there are the frogs and insects and there are a few night birds, like screech owls that are calling. But, then you hear the sounds of these birds. A lot of these nocturnal migrants are calling in flight, doing these little chip notes, little buzzes and things. And you hear more and more of that as the birds come lower. And some of them are coming in from the south and landing in the trees. But then as it starts to get light, you look out and there's small birds sort of flying along, paralleling the edge of the lake. There are others that are actually coming in from the north. Because, when these birds are migrating, if they're out over the open water when it gets light, they'll actually climb up somewhat higher and look around. We know this now from radar studies, right at dawn, we have birds arriving from all direction. Some are just pitching into the trees, some are flying along, paralleling the shore of the lake. And it's just an amazing amount of movement. It's just, it's like the whole world is alive with this movement of birds.

CURWOOD: How do they know where to go?

KAUFMAN: You know, that's a question that people have been working on for a long time. It's an amazing instinct that these migratory birds have. There are some kinds of birds that actually learn their migratory routes. Some things like cranes, for example, or swans or geese, the young birds just follow along with their parents and learn the route. So it's a tradition thing, not so much an instinct. But on the other hand, most of the small migratory birds, they're just going on instinct. And you can just leave a warbler, just drop it off in the north woods, and it will find its way from northern Alberta, perhaps, down to Brazil, without any guidance, without anyone showing it where to go. It's amazing that they've got this instinct. And then a lot of these small birds that migrate at night, they can navigate by the stars, they can detect the Earth's magnetic field. A lot of them can hear very low-pitched sounds, so they can hear, like, the sound of waves crashing on the beach from many miles away. We're still figuring out and still learning some of the things they use, but the navigational abilities of these birds are extraordinary.

CURWOOD: And yet we use the phrase birdbrain.

KAUFMAN: (LAUGHS) Yeah, I think birdbrain should be considered a compliment.

The Blackpoll Warbler is an extreme migrant among the warbler family, nesting across Canada and Alaska, wintering east of the Andes in South America. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

CURWOOD: So, in your book, you mentioned that birding is now seeming to become a more welcoming and diverse hobby. Talk to me a bit about that, and why you think that may be.

KAUFMAN: When I was a kid, birding was mostly a hobby for really well to do, you know, older white people. And even just as being a kid, I was sort of an oddity. And I once I wrote some books about birds in nature, and I started traveling around the country, speaking to bird clubs and things, it was really disturbing to me to see that I could go to some place where I knew that there was a very diverse local population, but I'd look out at the audience and just see a sea of white faces. And these people were all, you know, they were all perfectly nice, but I was just thinking about people who are not there. But now there are a lot of people who are starting to break down the stereotypes and the old barriers. And so when I go out in my local area on the boardwalk Magee Marsh to look at the migrating warblers in spring, I see a really diverse crowd. They're getting more and more families coming in. There are more people of color, there are people from other countries and other continents coming there. We're seeing lots of young people and every birdwatcher knows that diversity is good. You know, you want to go out and see lots of kinds of birds. You want to go out and see lots of kinds of people looking at birds. So to me, this is the best thing about what's happened in recent years.

CURWOOD: Kenn, what are some of the top locations here in North America that you suggest for migration birdwatching?

KAUFMAN: Some of the areas that are really outstanding in spring include the upper Texas coast, going over into Southwestern Louisiana. Just amazing numbers of breeds that stop off there in certain conditions in spring. There are places out on the Great Plains that are wonderful for shorebirds, some of the wetland areas in Kansas, for example, Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivira refuge in Kansas sometimes have amazing numbers of sandpipers that have come from South America and are headed to the Arctic. There are places in Florida, the Dry Tortugas off the end of the Florida Keys, wonderful area for migratory birds. And then when you turn it around and start looking in fall, there's a different set of places so that, for example, Cape May, New Jersey is one of the best places in the world to see migratory birds in fall. The area of Duluth, Minnesota right at the western end of Lake Superior is a fabulous place for fall migration.

CURWOOD: By the way, what have you observed in terms of climate change affecting bird migration?

KAUFMAN: I don't know any bird people who deny the reality of climate change, the fact that it's happening, and we're starting to see how it has an impact on birds. There are quite a few areas now where there are long term studies where we know that the birds are arriving earlier in spring. Arriving on average, like five to 10 days earlier. And in some cases, that puts them in difficult situations, because in some places, the birds are coming back a few days earlier, but the trees are leafing out much earlier than they used to. So the peak of insect populations now may be happening earlier in the season. And the birds are not in sync with it the way they would have been at one time. And I think we're still in early stages of it, and still in early stages of the studies. But I think we're going to see more and more impacts of climate change on these migratory birds.

CURWOOD: May be climate change, it may be chemicals, it's unclear, but there does seem to be a mass insect collapse going on. How do you think this is affecting the migrations for that matter, the whole business of being a bird?

KAUFMAN: Well, certainly a decline in inside populations is bad for birds, the majority of bird species in the world do feed on insects. So they're like the basic main item on the menu. One thing that's been determined recently is that, for birds that are wintering in the Caribbean, for example, there are long term studies in Jamaica, they found that if it's a really dry, warm winter, and insect populations are low, some of the migratory birds leave later in spring. You would think they would leave earlier just wanting to get out of dodge, because there's not much food. But apparently it takes them longer to build up fat reserves that they need. And that puts them at a disadvantage when they get to the breeding grounds. But this kind of thing is likely to happen all over the place. So decline in insect populations is going to be bad for birds across the board.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the more interesting illustrations in your book is a picture of a billboard that you bought of warning of the dangers of wind turbines. What's your concern?

Kenn Kaufman encourages thoughtful planning on the placement of wind turbines in his book. (Photo: Courtesy of Kenn Kaufman)

KAUFMAN: Well, I have to say, I'm not opposed to wind power, I don't think it's a bad thing. I think wind power is a really important source of renewable energy. And it's really worth developing, I just think the location is important. If you put up a wind turbine, any place, it's likely to kill a few birds. And that's just the way it goes. We can't take all the things threats to birds out of the environment. And it's so important to have green energy that, you know, we'll accept the fact that there's going to be some mortality of birds with these big spinning blades. But there's some places where wind turbines are going to kill so many birds that it's just not worth the risk. And one of the types of places where wind power is really a problem is in this major stop over habitat for birds. Like where we are on the shore of Lake Erie, there are all these nocturnal migrants coming in. They're landing in the dim light just before dawn, they're taking off in the dimness, just after it gets dark. And so they'd be going right through the sweep of these rotor blades on the wind turbines. Whereas a wind turbine out in the middle of farm country someplace, might not really be that damaging for bird life. Here on the lakeshore, in the middle of this stop over habitat, it could really do serious damage to populations of these long distance migrants that are already facing so many threats.

CURWOOD: For those people who live at a stop for birds on their migratory path, what can they do to make their local environments more welcoming and helpful to these traveling birds? Keep your cats inside, grow native plants, eliminate or at least reduce the use of chemical pesticides? And anything else, Kenn?

KAUFMAN: I really appreciate that question because that's something that's relevant everywhere. Just supporting conservation efforts in general, supporting protection of native habitats. There are cases where just by voting on certain issues, people can affect what happens with wildlife habitat in their local area. It's worthwhile for people to educate themselves about the issues and pay attention to what policy changes are going to have an impact on bird life.

Kenn Kaufman is a renowned birder and naturalist (Photo: Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

CURWOOD: Before we go, what do you hope readers will come away with after reading your book?

KAUFMAN: I'm hoping that people who read the book will learn something about the science of migration. But if I, if people were to come away with one thing from it, I hope they would just be taken with just the sense of wonder. Just the fact that this is an amazing, miraculous thing that we're seeing. And it, it happens everywhere. So it's a true miracle that happens twice a year, and that you can witness just about everywhere. And I think the more you learn about it the more magical it becomes. And, so, just the blend of science and magic is the one thing that I hope that people will take away from the book.

CURWOOD: Kenn Kaufman's book is called "A Season on the Wind: Inside the World of Spring Migration." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAUFMAN: Well, thanks, Steve. It's always great to talk with you.

Related links:

- Kenn Kaufman’s Official Twitter

- More about Kenn Kaufman

- Audubon | “Kenn Kaufman's Backyard Is One of the Best Spots to Witness Spring Migration”

MUSIC: Brian Rolland, “Lioness” on Long Night’s Moon, 2000 On The Full Moon Productions]

[SOUND OF THE NEBRASKA CONEHEAD]

CURWOOD: And now we bring you an insect instrumental. The Nebraska conehead is part of the katydid or long-horned grasshopper family. But it’s not quite accurately named.

[SOUND OF THE NEBRASKA CONEHEAD]

CURWOOD: Yes, they have broad coneheads, but their range extends far beyond Nebraska to as far south as Mississippi, and east to Maryland.

[SOUND OF THE NEBRASKA CONEHEAD]

CURWOOD: Coneheads can be green or brown. They live along roadsides in weeds and brush, at the edge of fields and woods, and can often be found hanging on a stem of grass, conehead down. Lang Elliott recorded the Nebraska Conehead, and it’s included on his CD called “The Song of Insects.”

[MUSIC: Brian Rolland, “Lioness” on Long Night’s Moon, 2000 On The Full Moon Productions]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. We welcome our new intern Joseph Winters this week. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth