May 3, 2019

Air Date: May 3, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Refugee Camp Becomes a City

View the page for this story

Driven by civil war, hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese families have fled their home country to neighboring Uganda in the last few years. In Uganda’s Bidibidi refugee camp, progressive policies that include local residents and enable refugees to live, farm, and work freely together are fostering the growth of small businesses and infrastructure. The goal: to attract outside investments and build a future city that could endure long beyond the refugees’ eventual return home. Nina Strochlic, a staff writer for National Geographic Magazine, sits down with Host Steve Curwood to discuss how temporary refugee camps can be transformed into rising cities. (11:20)

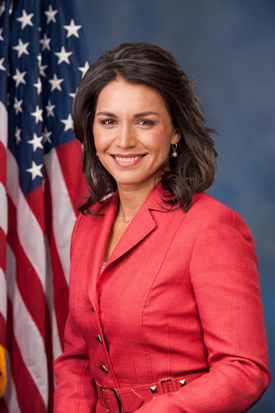

Tulsi Gabbard’s Presidential Bid

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Representative Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) is running as a Democratic candidate for President. At a recent hall meeting held in Exeter, New Hampshire, Congresswoman Gabbard spoke about the importance of addressing climate change and reducing military spending on trying to change regimes in other countries. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports from New Hampshire. (08:47)

No-Show Green Voters

View the page for this story

About 20 million registered voters in the US list the environment as one of their top two priorities. But compared to other voters they’re more likely to stay home on Election Day. These "super-environmentalists" are also more likely to be in a minority group -- they're often African-American or Hispanic -- and they tend to be young and live in cities. Founder of the Environmental Voter Project, Nathaniel Stinnett, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what it might mean for environmental policies if these 20 million "super-environmentalists" registered voters actually show up at the polls in greater numbers and what his organization is doing to get out that green vote. (11:33)

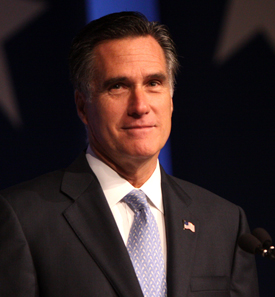

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Looking beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra takes Host Steve Curwood to the sinking Indonesian capital of Jakarta. The city has been plagued by subsidence and groundwater depletion, prompting the government to consider relocating to a safer, drier place. They then discuss the green jobs market and its promise to deliver higher wages and lower entry barriers, and conclude with a history calendar note on Utah Senator Mitt Romney. 15 years ago, as Governor of Massachusetts, Mr. Romney signed a groundbreaking Climate Action Plan, but shifted his beliefs on climate change after entering the 2012 presidential race. (03:50)

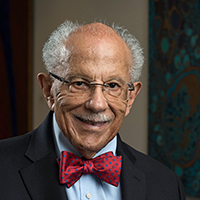

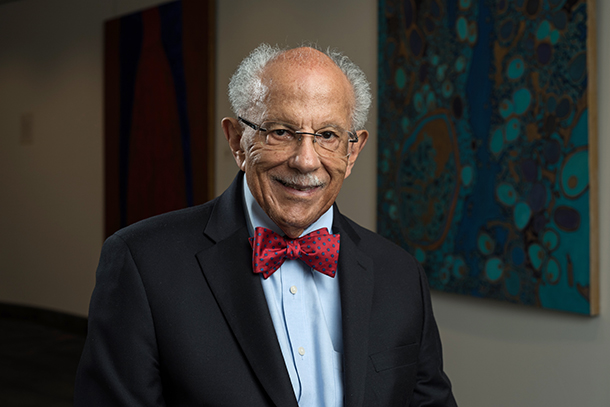

Pioneer Warren Washington Wins Tyler Prize

View the page for this story

Warren Washington, a distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, spent the first years of his more than five-decade career as a key developer of some of the earliest computer models of global climate. A pioneer among African American scientists, he has received multiple awards in recognition of his contributions to the field of climate science, the latest being the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, which he shares with climatologist Michael Mann. Warren Washington speaks with host Steve Curwood about his career, the climate challenge, and leading the way for fellow scientists of color. (11:18)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nathaniel Stinnett, Nina Strochlic, Warren Washington

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Registered voters who lean green tend to vote less reliably than the general population, but there are ways to improve turnout.

STINNETT: Politicians go where the votes are. And so if you get more environmentalists to vote, any politician, whether they're liberal, conservative, or in the middle, they're going to pay attention, because they're in the business of winning elections.

CURWOOD: Also, Democratic presidential hopeful and Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard from Hawaii on her relationship with the environment.

GABBARD: Growing up as a kid, the ocean and the mountains was our playground. When I first learned how to swim, I was in the ocean and grew up surfing and just having a deep appreciation for our environment. It was something that was a part of our culture and just something that came naturally.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

A Refugee Camp Becomes a City

Photo of a mobile business in Bidibidi. (Photo: Nancy Ostertag, courtesy of National Geographic)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The category four cyclone Kenneth recently slammed ashore in sparsely populated northern Mozambique, killing dozens of people, displacing thousands, and setting off massive flooding. Kenneth was the strongest cyclone ever recorded in this part of Africa, and came on the heels of cyclone Idai in March. Idai was a category three storm before it barreled into Beira, a city of a half million further south in Mozambique. Idai killed nearly a thousand people, leveled more than 110,000 homes, and flooded many parts of Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe. The scale of the devastation is massive and aid workers caution that long-term assistance and refugee camps will be necessary.

For inspiration, Mozambique might look north to Uganda, where the government and international agencies have taken an innovative approach to housing displaced persons by building more permanent facilities that serve both refugees and local residents. Bidibidi refugee camp houses roughly a quarter million South Sudanese who fled civil war in their country. Until recently it was the largest refugee camp in the world. Nina Strochlic recently traveled to Bidibidi for National Geographic magazine and joins me now.

STROCHLIC: Thanks so much for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: What was the landscape like when South Sudanese refugees first settled in Uganda?

STROCHLIC: Well, when refugees started coming over the border with Uganda in late 2016, they were more or less entering a forest. They were in a very densely forested area that had to be immediately adapted to fit the tens of thousands of people who were coming to stay. So they ended up clearing acres and acres of land, and the first thing they did was they made 250 miles of roads going through.

CURWOOD: Oh my. Nina, I understand that there are now around a quarter million, perhaps 250,000, South Sudanese individuals in Bidibidi. So what about access to food and water?

STROCHLIC: Yeah, well there's a really interesting way of managing that that they have created in Bidibidi. So every month South Sudanese refugees get corn and oil and sort of the basic staples that they need to survive, but it's certainly not enough for a family. So what they've done in Bidibidi is they've given everyone plots of land. And on those plots, people build their homes, sort of a family-style cluster of homes. And they also have room to grow food, so fruits and vegetables, maybe peanuts to make peanut butter to sell, sunflowers to make oil, things that they can supplement their diet with. And they are also able to get a second area of land a little bit outside of camp center where they can do more agriculture and use that as a job and a way to survive. What you see when you first enter Bidibidi is that it doesn't feel like a refugee camp where you're imagining tons of white tents crammed together, tarps, really temporary-looking structures. You see solidly-built, small huts with thatched roofs like you might find across East Africa. And around that, little areas of land that people are using to farm.

CURWOOD: These are nice resources to have in East Africa, where there are many, many challenges. What access do Ugandans have to these facilities? Or are they strictly available for refugees?

STROCHLIC: One of the major sort of turning points in the international response in Uganda and for the South Sudanese crisis was that the Ugandan officials wanted to make sure that an influx of hundreds of thousands of people, over a million at this point, wouldn't create tensions with local populations. So what they did to ensure that locals would feel that the refugees were not taking resources that might have been available for them, is they earmarked 30% of all international funding to go towards local amenities. So what that means on the ground, for example, is if a school is built, they're hoping to get 30% of those students as local students, 70% refugees. If a health center is built, they want 30% of the resources from that to go to local communities. So that it's more of a shared benefit and it doesn't feel like the government and the international community only cares about the refugee population and doesn't care about normal Ugandans.

CURWOOD: So how is that 30% number arrived at, do you think?

STROCHLIC: In 2016, the UN announced its comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, which is basically aimed at trying to get host populations to incorporate refugees more into their economy, and saying, you know, it doesn't serve anyone to stick a bunch of people in a remote area, having them live on food rations and in tents, and unable to work, unable to do anything to help themselves for, it could be, decades. There are camps around the world that have existed for decades and decades and still haven't, you know, been fully utilized, where people feel that they are able to sort of self-sustain. So how you see this new policy play out on the ground, is that the schools, the health centers, and other infrastructure are being built for permanence. So they're not tarps, though there still are some temporary structures. But for the most part, they're very nice looking brick and mortar buildings. And the hope is that, regardless of how long the refugees stay there, those buildings will last and they'll serve the local population for years to come.

CURWOOD: Let's cut to the chase though: there has to be economic activity. So how at Bidibidi are people able to have incomes and move forward with setting up a life for themselves, not just existing, but having a life?

Hair salons are a hot commodity in Bidibidi just like any other city. (Photo: Nancy Ostertag, courtesy of National Geographic)

STROCHLIC: People I spoke to who had been there in the early days said, of course, supply and demand. So when people started coming over the border, it was not long at all until a market popped up around that main reception area. And now you can see markets in every zone of the camp and within villages in each of those zones. So there's definitely a small-scale economy that is flourishing in the camp. A lot of what you see are small snack stands, people selling the produce that they're growing outside of their plots, used clothing markets, seamstresses, and then there are even the things that you would find in a normal city to entertain yourself. There are TV halls all around the camp, where people can pay a small amount of money and watch Nigerian movies or soccer games, or the World Cup that's going on. There are, you know, places where people will just relax and, like we would anywhere in the world, play pool or dominoes or, you know, get their hair cut.

CURWOOD: Uganda is not exactly one of the wealthiest places on the planet itself. The government is stable these days, but they need a lot as well. So how are locals reacting to Bidibidi becoming a more intentional, more supported settlement, become a city, really?

STROCHLIC: The locals who I interacted with were mostly within the camp or lived in the towns and the villages, sort of interspersed within many zones of Bidibidi, and people said they were really hoping for employment opportunities in that area. Specifically, these large humanitarian organizations who come in and hire drivers and cooks and construction workers and all of these things. And I think they were a little disappointed that there weren't more opportunities for them to work for the large NGOs who are operating around Bidibidi right now. But people then would also say, you know, that they could come into the camp, they could go to the health clinic, they could get medical attention that they were not able to get before. They could send their kids to school if they were living right next to one of the camp zones. And it also provided potential markets. So there were vendors in the markets, who were local Ugandans, who saw this large influx of people and thought, hey, if I open a charging station, people need to charge their phones, they'll pay me a little bit of money for that. Or I could import sodas from Kampala, eight hours south of the camp, and bring in things that aren't readily available in the region and sell them and get some income that way. So local Ugandans are definitely seeing benefits of having a quarter million new people moving into the North. But I wouldn't say they're overjoyed at it. And I think that's what makes the efforts of the Ugandan government to ensure that there's sort of this shared benefit for both locals and refugees really important because without that dialogue going on, tensions can arise. And that's where conflict becomes possible as well.

CURWOOD: So if Bidibidi is so successful as a refugee camp, what happens suddenly if South Sudan is a peaceful place, and refugees could go back? What will happen to this city, do you think?

A church service being held at Bidibidi (Photo: Nancy Ostertag, courtesy of National Geographic)

STROCHLIC: So the idea is that in the future, say it's possible for South Sudanese refugees to return home, I think many people would like to do that, even though they understand that could be many years from now. But the infrastructure that remains is intended to be put to use for local Ugandan communities. That's how the camp was built, with that future in mind. And if it doesn't come to fruition, well then, it will be used by South Sudanese for years to come. Or if it does, it'll hopefully be integrated into Uganda and used by Ugandan locals.

CURWOOD: Nice problem to have, I imagine.

STROCHLIC: Yeah.

CURWOOD: So refugee camps are big business these days on this planet, whether it's a conflict zone, in Syria, or in Bangladesh, where the Rohingya have had to flee. But also in Bangladesh, you have climate refugees. What do you think the United States could learn from the experience of Bidibidi when it comes to dealing with refugees who come to our borders?

STROCHLIC: I think there's definitely a beneficial lesson in Bidibidi that shows that if refugees are given the opportunity, they will do everything they can to become self-sufficient. And that, in the end, can benefit the society as a whole. So there are a lot of people in the international community thinking now that we've existed for hundreds of years in this sort of mindset where refugees are just to be temporarily held and then returned as quickly as possible to the country where they came from. But that almost never happens. There are statistics that show that refugees stay in exile for 10 years on average now, and certainly with some of the wars that we're seeing happen in the world that could be a lot longer. So trying to change that mindset is really something that's on the table now, on the international level. And I think that in the US we could be looking at that as well.

CURWOOD: Nina Strochlic's article about Bidibidi is in the April issue of National Geographic. Nina, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

STROCHLIC: Thanks, Steve. It was great to talk with you.

Related links:

- How Bidibidi Uganda Refugee Camps Became a City

- American Refugee Committee | Welcome to the Bidibidi Refugee Settlement

- The Guardian| Inside the World’s Largest Refugee Camp

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XaGuniEqQEY

Samite of Uganda, “Embalasasa” on Embalasasa, Triloka Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – How to encourage environmental voters to turn out at the polls. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsForTheSea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hsSKCmMP8k

Samite of Uganda (Abaana Bakesa), “Muno Muno” on Pearl Of Africa Reborn, Shanachie Records]

Tulsi Gabbard’s Presidential Bid

Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) speaks at an Exeter, NH town hall meeting. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

With the New Hampshire first-in-the-nation presidential primary fast approaching, there’s a steady parade of the 20-candidate Democratic field passing through the Granite State. They include Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii. At age 38 she has represented Hawaii’s second district since 2013, but she got her start in politics in the state legislature. Tulsi Gabbard was just 21 years old at the time, which made her one of the youngest female state representatives in US history. She left the state government to join the Hawaii Army National Guard and served two tours of duty in Iraq and Kuwait. Representative Gabbard recently campaigned in Exeter, New Hampshire, where Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb caught up with her.

[SFX CROWD SOUNDS INSIDE TOWN HALL]

BASCOMB: A crowd of about 100 people gather in the historic Exeter town hall, where Abraham Lincoln spoke back in 1860. The wooden seats are filled and a handful of people stand at the back of the room. As people wait for Tulsi, plastic flower leis are handed out by staff and volunteers, including Doug Brenner, who says he likes Tulsi’s environmental record.

BRENNER: She talks about how important it is for all of us to breathe clean air and to have clean water and she talks about environmental issues in a very bipartisan way because it’s not just one party or the other that wants clean air. It’s something that we all need.

BASCOMB: Indeed, the League of Conservation Voters gives Tulsi a 96% lifetime voting record, meaning LCV believes she has voted in favor of the environment 96% of the time.

[CROWD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Tulsi is a lifelong vegetarian and a practicing Hindu, like her mother who is of German descent. Her father is American Samoan and Catholic. Many supporters, including Doug Brenner, say they are impressed by her military service and platform for peace.

[SFX CROWD CHANTING “TULSI, TULSI, TULSI”]

GABBARD: Aloha.

CROWD: Aloha!

GABBARD: It’s so great to be back here in Exeter, it’s so great to be back here amongst all of you. Hearing your voices, hearing your resounding aloha filled my heart….

BASCOMB: Congresswoman Gabbard talks for about 45 minutes, much about the need to scale back on military intervention abroad. She says there is a peace dividend to be had when we stop spending trillions of dollars on regime change wars. We should instead invest that money domestically on health care, infrastructure and the environment.

GABBARD: Every single one of us is paying the price for these wars. And we see this every time we are told by politicians that there is just not enough money. There’s just not enough money to make sure that mothers and fathers and sons and daughters in places like Merrimack, New Hampshire have clean water to drink. There’s just not enough money to make sure that we have safe roads and bridges to drive on.

BASCOMB: As she closes, Tulsi brings her audience to its feet.

GABBARD: When we stand united we can bend that arc of history away from war and towards peace. This is what I’m asking you to join me in doing: revive that vision our founders had that our government is of, by and…

CROWD: For the people.

GABBARD: Let’s try that one more time. And…

CROWD: For the people!

GABBARD: Thank you all so much for being here. Aloha!

[CLAPPING, TULSI, TULSI, TULSI]

[SFX CROWD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: After her speech I caught up with Ms. Gabbard to chat for a few minutes.

BASCOMB: You grew up in Hawaii, surfing, how did that inform your relationship with the environment?

GABBARD: Tremendously. You know, growing up as a kid, the ocean and the mountains was our playground. When I first learned how to swim, it was in the ocean and grew up surfing and just having a deep appreciation for, for our environment. You know, it wasn't something that had to be taught to me as you know, a political issue or here's something you have to do. It was something that was a part of our culture, growing up and just something that came naturally in saying, hey, this is our home, and we've got to do what we can to protect it. And it's what inspired me to run for the State House in Hawaii when I was 21 years old, my concern about these environmental issues and impacts.

Representative Gabbard has served in the Hawaii Army National Guard since 2003. She was promoted to Major in 2015. (Photo: Office of Representative Gabbard, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: What were you concerned about back then and what concerns you most about the environment today?

GABBARD: Unfortunately, they're very similar - water quality. The impact on our water, both on our oceans, but also back then we were dealing with issues like landfills being built over some of our largest aquifers, and threatening the very source of really beautiful water that we have to drink in Hawaii. And today, this is one of the main concerns that we continue to have that afflicts so many people in this country, I think more than many folks realize. You know, we heard about Flint, Michigan in the headlines for a little while. Unfortunately, they have been out of the headlines for a long time, but their water is still toxic, their water is still poisonous. Water is life, it is essential to everything else. If we don't have clean water to drink, then we'd have nothing.

[CROWD AMBI UNDER TRACK]

BASCOMB: Back in 2016 as a person of native Samoan decent, Tulsi traveled to North Dakota along with thousands of Native Americans and other military veterans to join the Standing Rock Sioux in rejecting the Dakota Access Pipeline. Tulsi says her decision to join the Sioux tribe was in part motivated by her concern for water safety.

GABBARD: It's hard to describe in words, what it was like to go to Standing Rock to meet with the leaders of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, to see the unity amongst tribes that had come about because of this recognition that water is life and that unless we all stand together to protect our water from the very real threats that we face -- there it’s an oil pipeline, and in other places it's other things but unless we stand together, recognizing that a threat to our water in one place is a threat to our water everywhere, then then we are threatened and destined to perish.

I've kept in touch with the leaders of the tribes there. And the beautiful thing is that they have made a commitment to take all of their community, to take their reservation completely off of any dependence on fossil fuels, and be self-sufficient and reliant on their own green renewable energy economy.

Tulsi Gabbard is a Democratic Congresswoman from Hawaii and a veteran of the Iraq war. (Photo: United States Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Representative Gabbard has not co-sponsored the Green New Deal resolution to tackle climate change. She’s concerned that the language of the resolution introduced is too vague. But, in 2017 she did introduce a measure that would eliminate tax breaks for fossil fuel companies and provide transitional support for workers in those industries, and its goal was for the US to generate 100% renewable energy by 2035.

GABBARD: We have to address the seriousness of this threat and stop treating it like a political football issue. And we can and must do so by recognizing that the effects of climate change are threatening people in communities all across the country, are threatening people everywhere, whether you're in a Republican state or a Democratic state. And in order to bring about the kind of big change that we need to see, we have to come together and unite towards making the big investments that we need to make -- to get off of fossil fuels, and invest in a green renewable energy economy, to invest in a workforce to work in that economy, to invest in sustainable infrastructure, to invest in sustainable agriculture, something that's not often talked about when we're dealing with climate change, but is one of the biggest contributors of carbon to our environment and to our atmosphere. And we have to be real about the fact that even as we must do all that we can here in this country, it still won't be enough, unless we build relationships based on cooperation rather than conflict with other countries that are big contributors to this threat, countries like China, for example. And while we have differences in certain areas, this is an issue that is a global crisis, and can only be addressed with global action.

BASCOMB: After our chat Tulsi shakes hands with New Hampshire voters. She greets nearly everyone with a handshake and a warm “aloha”. She says “aloha” means much more than just hello and goodbye. It’s an expression of love, kindness, and mutual respect, both for people and the land. Much like our first president from Hawaii, Barack Obama, Tulsi hopes that the spirit of aloha will carry her all the way to the White House.

BASCOMB: For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Exeter, New Hampshire.

Related links:

- Tulsi Gabbard’s 2020 Presidential Campaign Website

- Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs | “Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard-Build Don’t Bomb: A New American Foreign policy”

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpfT8AzAl0c

Ledward Kaapana, "Kolomona Slack Key" Kihoʻalu: Hawaiian Slack Key Guitar, Rhythm & Roots Records]

No-Show Green Voters

The Americans who care most strongly about the environment are more likely to be African-American or Hispanic, make less than $50,000 a year, and live in cities. These populations are among those most affected by environmental justice issues – and tend to vote less often than other demographics. (Photo: Becker1999, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Congresswoman Gabbard may appeal to environmentally-minded voters, but it’s a tough crowd to get to the polls. Surveys show the majority of registered voters who say the environment is a top priority for them didn’t bother to cast a ballot in the most recent midterm elections in the US. To increase the turnout of environmentally concerned voters and thus influence environmental policies, the non-partisan, non-profit Environmental Voter Project was founded. Nathaniel Stinnett is the Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project, and we’ve been following his work. His group tried an experiment to increase turnout among green-focused registered voters in the midterms and he is with us today to discuss the results. Nathaniel, welcome back to Living on Earth!

STINNETT: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Remind us, please, of your criteria. How do you determine if a voter is what you call an environmental voter?

STINNETT: So we have a very stringent set of criteria. We are only going after people who care so deeply about climate or other environmental issues, that it's their number one priority, over all others, or their number two priority. So these are people we like to call “super-environmentalists”.

CURWOOD: And, demographically, who's most likely to be a “super-environmental” voter?

STINNETT: Well, it's not who you might think. It's not yuppies, in fleeces, jumping out of their Priuses. It is far more likely to be Latinos, African Americans, often people who make less than $50,000 a year, and usually people who live within five or 10 miles of an urban core. With each passing year, this is increasingly a population of poor people, and people who tend to be part of minorities.

CURWOOD: Why do you think so many people of color are in this category of being super-environmentalists?

STINNETT: People of color and poor people are far, far more likely to be on the front lines of climate change, of air quality issues, and water quality issues. So it should come as no surprise to us that the people who care most about these issues are the ones who are being impacted the most by these issues.

CURWOOD: And at the same time, these people don't vote so much.

STINNETT: That's right, they don't. The environmental movement does not have a persuasion problem. There are tons of people who care deeply about environmental issues. We have a turnout problem, we're not showing up on election day. And it's starting to get a little bit better, but it's not getting better fast enough.

CURWOOD: So what do you think it is that holds people back?

STINNETT: We don't know for sure. But let me tell you what we do know, because we know some of the reasons why these people aren't voting. One reason is, as we discussed previously, we know that if you deeply care about the environment, you're more likely to be Latino, African American, poor, and probably young. And those four groups that I just mentioned, they tend to vote less often than the general electorate does. So part of what's going on here is just a basic demographic correlation. But here's the really interesting thing, Steve, if you only look at Latinos, the ones who care about the environment vote less often than the other Latinos. If you only look at young people, the ones who care about the environment vote less often than other young people. So there's something else going on there. And I'm not going to pretend like we know what it is. We've researched it over and over and over again. And it's really hard to figure out. I can tell you some of the excuses that people give. Some people are saying, oh, politicians don't care about the issues that I care about. I think that's probably accurate. But you know how to change that Steve? Vote! Vote! [LAUGHS] So that's part of what we're trying to do here.

I think another thing that's going on is ballot access issues. In any state, where there are laws and regulations that are making it harder for people to register to vote, or harder for people to show up on election day, usually, those laws are making it harder for people of color or young people to vote. And those are the environmentalists. I think it's very important for the environmental movement to internalize this. We're getting better when we talk about environmental justice issues, to realize that environmental issues are often civil rights issues. But it goes the other way as well. Chances are, if there is any civil rights issue at play, it is also disproportionately impacting the environmental movement, because the environmental movement is disproportionately made up of people of color, poor people and young people. And so environmental groups really need to pay attention to ballot access issues. If there is a state that makes it harder for people of color to vote, that means that fewer environmentalists are voting, and that's hurting our ability to impact policy making.

CURWOOD: Now, your organization focuses on increasing voter turnout, rather than campaigning for any particular candidate or issue. How exactly does that work?

Instead of advocating for particular candidates, the Environmental Voter Project focuses on turning out larger number of environmentally conscious voters at the polls. The EVP believes this is key to making politicians act on the climate crisis. (Photo: Marc Nozell, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

STINNETT: So, we essentially do two things: we focus on data science and behavioral science. So the first part of it is, we will poll tens of thousands of people to try to identify people who are these super-environmentalists we're talking about, people who care so deeply about climate or the environment, it's one of their top two priorities. Then, we don't talk to the people who are already good voters, they don't need our help, we only focus on the ones who aren't voting. And that's when we shift into the second part of what we do, which is behavioral science. We already know that these people are with us, Steve. So we're not trying to change their opinions about anything. We're just trying to change their behavior, we're trying to turn them into better voters. And the good news at that point is, we can afford to use whatever works, because we don't need to change these people's minds. And so we can take advantage of all of this great research, and just use the messaging that we know has the highest likelihood of getting their rear ends out the door on election day.

CURWOOD: And that is?

STINNETT: We try to take advantage of the fact that we are social animals, not rational animals. So instead of trying to rationally convince someone who cares about a particular issue of the value of their vote, instead, we send them letters telling them how many of their neighbors turned out last time there was an election. Or we used very normative categorical statements like 'real environmentalists vote', or we'll have a canvasser get someone to promise to vote, and then we'll follow up with that voter and we'll say, “Don't you want to be an honest promise-keeper? Follow through on your promise to vote!” We take advantage of these norms that we all buy into, because we've realize that we're not all walking around in a cost-benefit analysis, we're social beings.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about a particular place where you have used these techniques and how people responded.

STINNETT: So a perfect example is we were targeting almost 900,000 unlikely-to-vote environmentalists in Florida. And what we did was, we never tried to rationally convince them of the value of their vote. We never tried to tell them, hey, you care about the environment, or you care about climate change, this is why you've got to vote. We know from all of our previous work that that doesn't work. Instead, we worked with over 2000 volunteers to text and call and canvass these voters. And we sent them direct mail and we sent them digital advertisements. But all of them, all of the messaging, and all of those media, simply focused on these sort of normative, peer-pressure focused messages that I discussed. And you wouldn't think that that would make a big difference. You'd think, gosh, this is like, really juvenile messaging, you're essentially using everything we learned in fourth grade. And you'd be right to think that.

But the results were extraordinary. In Florida alone, we increased turnout 2.2 percentage points among the people we were targeting. And that might not sound like a lot to you. But we were responsible for adding over 17,000 brand-new environmental voters to the electorate in Florida. And what we know, Steve, I know this sounds cynical, but it's just the truth, is that politicians go where the votes are. And so if you get more environmentalists to vote, any politician, whether they're liberal, conservative, or in the middle, they're going to pay attention, because they're in the business of winning elections.

In 2016, the climate crisis was all but ignored in the presidential debates, but several Democratic presidential hopefuls for 2020, including Jay Inslee, have made the climate a priority for their campaigns. (Photo: Jay Inslee, Office of the Governor, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, we're talking at a time that the Democratic field of contenders for the presidency is fairly large. And that means in the early primary, relatively small numbers of votes can make a huge difference. The percentage or two can be huge in the early going.

STINNETT: Well, you're absolutely right, a percentage or two can be the difference maker. And I think we're seeing something really extraordinary go on in American politics right now. Because four years ago, in the Democratic primary, no one was talking about climate change and environmental issues. They weren't. And now, almost everybody is. Signing on to the Green New Deal is almost seen like a litmus test. You have particular candidates, like Jay Inslee, centering their entire presidential campaign around climate change, but you also have other candidates talking about it quite a bit. And this is really extraordinary. A Monmouth poll of likely caucus goers in Iowa, showed that they list climate change as their second most important priority, and environment and pollution as their fifth highest priority. So my advice for people running for president is, talk about this issue. It's what voters increasingly want to hear about.

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

But, there's a huge caveat here, Steve. We're not seeing that yet in the general election numbers. When you sweep in Independents, and Republicans and also ten millions of new voters of all persuasions who are going to vote in the general election, climate and environmental issues are at best sixth, seventh, eighth, on people's lists of priorities. And I think this is why you're seeing Democrats who are running for president on the stump in New Hampshire promote the Green New Deal. And then when they're back in DC in the well of the Senate, they don't sign on to it. And it's because they're trying to appeal to two different electorates at once. And I think this illustrates perfectly the importance of voting. Politicians go where the votes are. And they're starting to wake up to the realization that there are lots of climate voters in the Democratic primary. But they're also cognizant of the fact that there aren't yet enough climate votes in the general, and we need to change that.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel Stinnett is founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Thanks so much for taking the time, Nathaniel.

STINNETT: It was my pleasure. Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- The Environmental Voter Project Website

- The Guardian | “’We Need Some Fire’: Climate Change Activists Issue Call to Arms for Voters”

- Listen to LOE’s previous interview with Nathaniel Stinnett

[MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, ”All Or Nothing At All” on Ballads, Blue Thumb Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A conversation with history-making Warren Washington, a winner of this year’s Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, ”All Or Nothing At All” on Ballads, Blue Thumb Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Indonesian capital of Jakarta, which is home to 10 million people, is sinking, causing the government to consider relocating to higher ground. (Photo: Jakarta, Indonesia, Gordon, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Time now for us to take a look beyond the headlines. And for this journey, we travel to Atlanta, Georgia to talk with Peter Dykstra. He is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And on the line, hey there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. You know, one of the world's great cities is sinking. Jakarta is home to 10 million people, it's Indonesia's capital. It's a major victim of subsidence. That's where marshy land forces whatever is built on top of it to literally sink. The other problem with Jakarta and those 10 million people - 10 million thirsty people - is that they're drawing down groundwater, which aggravates the subsidence problem even more. Add sea level rise to the mix, and it's prompted the Indonesian government to look into moving its capital.

CURWOOD: Okay, they could move the capital, but what about the 10 million other people?

DYKSTRA: Well, that's why they're not going to move the 10 million people, they're only going to move the people and the buildings associated with running the Indonesian government. They'll move them to a safer location, and Indonesia's planning minister said it's no surprise. They've known this for decades, it's bound to happen. They say that moving the government will also help alleviate pollution and traffic, and however many of the 10 million remain.

CURWOOD: I mean, if the government folks can get out of town and avoid getting flooded out, it still leaves the ordinary folks there.

DYKSTRA: Well, they have our thoughts and prayers.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Okay. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well there's a report out from the Brookings Institution about the green jobs economy, the clean energy economy that lies in our future. The Green New Deal didn't pass in Congress this time around, but it's really helped push up the dialogue about it. The green jobs economy promises, according to Brookings, that there'll be better paying jobs that'll be easier for many people to access, but it won't be an ideal new deal.

According to a new analysis by Brookings, the green jobs economy promises higher wages and lower entry barriers. (Photo: Solar Panels on Everitt, shantontcady, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's un-ideal about it?

DYKSTRA: What's un-ideal is that a lot of these jobs have tended so far to be focused toward whites and men. And the diversity aspect of it isn't that strong. But the economic aspect of it promises a $5 to $10 premium, according to Brookings, in what these jobs pay, not just in clean energy, but also energy efficiency, and then the planning and management aspects of both of those things.

CURWOOD: Five to 10 bucks more an hour really matters. All right, well let's look back now in history. What would you like to talk about today?

DYKSTRA: Coming up on the 15th anniversary, May 7, 2004, Massachusetts Governor - this is up by you guys - Mitt Romney spearheaded something called the Climate Action Plan. It was groundbreaking, not only because no other state had a similarly ambitious climate action plan, but it was spearheaded by a Republican.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but you know, just about when he was going to finish his term, he didn't quite sign what's known as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. Some said it was because he had his eyes on another job.

As Republican Governor of Massachusetts, Mitt Romney spearheaded a groundbreaking Climate Action Plan. He changed his tune just before entering the 2012 presidential race. (Photo: Mitt Romney 2011, Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, he left that to his successor, a Democrat named Deval Patrick, to sign for Massachusetts. And Mitt Romney, when he got to the 2012 presidential election, when he ran against Barack Obama, by that time, he was expressing doubt about climate change, just like a whole lot of other Republicans made a U-turn on the issue. Now he's a Republican senator from Utah. So we shall see how it all works out for Senator Romney.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- BBC | “Indonesia's planning minister announces capital city move”

- LA Times | “Mitt Romney worked to combat climate change as governor”

- CityLab | “A Bottom-Line Case for the Green New Deal: The Jobs Pay More”

[MUSIC: Jon Manasse/Jon Nakamatsu, “Three Preludes, 1. Allegro ben rimato e deciso” on Bernstein, Gershwin, Novacek, D’Rivera: American Music For Clarinet and Piano, by George Gershwin, Harmonia Mundi]

Pioneer Warren Washington Wins Tyler Prize

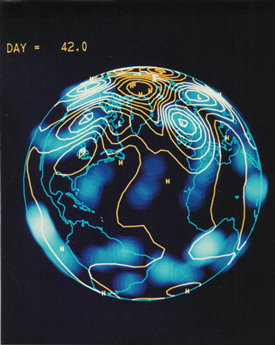

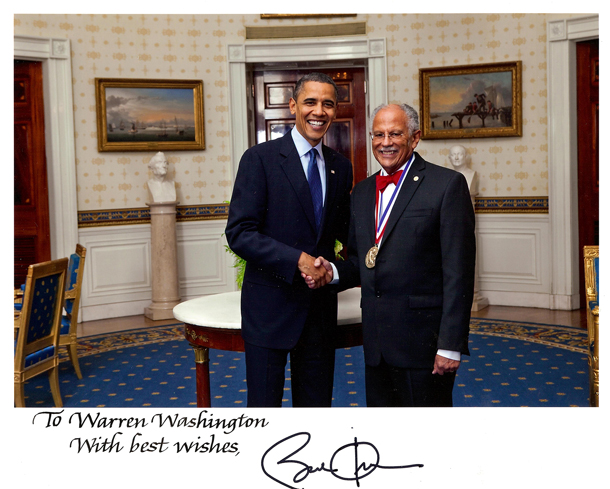

Warren Washington is a 2019 co-recipient of the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn)

CURWOOD: The world may be moving too slowly to fight climate change, but thanks to good science, at least we have been warned of what’s coming. And today we bring you a conversation with one of the pioneers of climate modeling, who built one of the first models more than fifty years ago and dedicated the rest of his career to improving them. As an African American he was also a pioneer in this mostly white world of science. Warren Washington recently retired from his position as a Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and has received many awards for his work, including the National Medal of Science, conferred by President Obama in 2010. Most recently he was honored with the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement alongside climate scientist Michael Mann. Warren Washington joins me now from Boulder, Colorado. Welcome to Living on Earth, and congratulations!

WASHINGTON: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So you're famous for modeling how the climate works and trying to identify how it's changing. Computing has changed radically since you first started working in weather and climate modeling back in the late 1950s. What was it like to model on those earliest computers?

WASHINGTON: It was very painful. [LAUGHS] Because it took essentially one day of computer time to run one day of simulation. So there was probably a little bit more emphasis on weather computing, because that's just a short two or three weeks at the most. Whereas climate, really you have to do at least a month or so in order to get anywhere. So sometimes it would be very slow. But things happen very quickly, and in the early 60s, in the fact that we were able to implement new computers every year or so. And the newer computers were sometimes two or three or four times as fast. So the technology was catching up.

Warren Washington’s first model, developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the late 1960s. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: Warren Washington, when did you begin to understand how serious the risks of climate change are, and what it poses to humanity?

WASHINGTON: Well, there was an interesting article that Jerry Meehl and I wrote in 1980, and it was published in a journal called Climate Dynamics. Well, the editor of Nature magazine, I believe his name is Maddox, wrote an editorial about our work on climate change. And he thought that this was the real start of a need to define special journals, a Nature series of journals, dealing with climate change issues, and that got us a lot of publicity. Then the other model simulation was in 1989, where we coupled, I think, on the first fully ocean to an atmospheric model, and it was picked up by Newsweek magazine. And John Sununu, who was the chief of staff for the President Bush -- the first President Bush -- said some things in there that weren't quite right in the article. So I sent a telegram to the White House saying, if you need some help understanding, please get in touch. And I was away at a meeting at Stony Brook. And I went home that evening; guess what, there was a call from John Sununu, asking me how I thought he was wrong. And he asked several mathematical questions; turns out he did his PhD at MIT, and he knew some of the numerical methods. So he wanted more details, so I sent him a copy of my book with Claire Parkinson. And I ended up installing a model -- a simple model -- in the White House so that John Sununu could do some experiments. And I spoke with the cabinet of the science agencies and departments. So I spent some time giving advice to him and to the others. As a result, I, over the years I've been an advisor on committees for five presidents.

CURWOOD: What did you take away from your science advising roles for those presidents?

WASHINGTON: I think that even from the very start, when climate change was becoming important, there was a struggle in between the members of the administration and the cabinet and so forth. Some of the members felt that this is a serious problem and they wanted to get started in doing something about it, by taking steps to cut back emissions. And others felt that no, we shouldn't do anything, because there may be an error in the models, or the models aren't quite, aren't good enough. And it comes about by the fact that the oil and gas industry, in my opinion, and the coal industry, has been contributing to one party in our country, more than the other, to essentially not do anything that will slow down the use of fossil fuel energy.

CURWOOD: It's about the money, isn't it?

WASHINGTON: Yeah. Because they're looking for people to sponsor their campaigns.

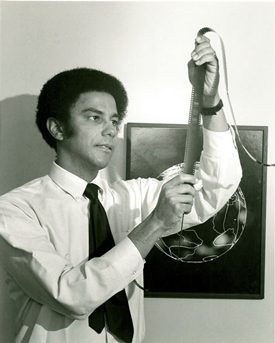

Warren Washington as a young scientist at NCAR. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: I understand that science has been a lifelong passion for you. What drew you to science as a kid, what was going on at home?

WASHINGTON: Early on, I was one of those nerdy kids who wanted to know how things worked. And I was really turned on in my junior year of high school when I had a lady teacher, I think her name was Mrs. Teeters. When I asked her in class, why are egg yolks yellow? She said, Well, why don't you find out? [LAUGHS] And that was intriguing, because that put me on the path of doing a little bit of research -- you know, not actual research in a laboratory, but library research about why egg yolks are yellow.

CURWOOD: By the way, what's the answer?

WASHINGTON: The answer is that there are sulfur compounds in the egg, and that's what you get the orange from. And of course, you know, eggs can, if they're rotten or something, can smell pretty bad. And that's hydrogen sulfide. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I imagine, what, junior year you take physics, is that it?

WASHINGTON: Yeah, I took physics in my senior year, but it was chemistry in my, in my junior year. I eventually ended up going to Oregon State University. And my advisor advised me not to go into science. But to switch over to business, he thought I would have more chance of success. I was pretty stubborn. I ignored his advice and stuck to science.

CURWOOD: Well, yeah, let's talk role models here. You consider yourself African American; how many African Americans did you see around you in the science community?

WASHINGTON: Very few. [LAUGHS] In fact, when I was at Oregon State, there were probably like 10 students or so, African Americans, at the university. I was the only one that wasn't on the football team.

In October, 2010 President Barack Obama named Warren Washington one of 10 eminent researchers to be awarded the National Medal of Science. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: Of course, then as a black scientist, you've not only done this groundbreaking research, but you've broken barriers. I'm looking at a, at a summary of your career that has you as the first black President of the American Meteorological Society, and then you're considered by many to be only the second black person to earn a doctoral degree in meteorology. Talk to me about what it's meant to you to be able to lead the way for other scientists of color.

WASHINGTON: Well, obviously, this has always been a problem of, we're not getting enough diversity in the, in the STEM fields. I've tried to work on that in effective ways. And President Clinton appointed me to the National Science Board, the governing board to the National Science Foundation; I eventually became Chair of the National Science Board. So I had an opportunity to press forward on trying to get programs to deal with the paucity of African Americans and other underrepresented minorities in science and engineering and so forth. I think we've been successful. I think there's real serious attitudes at academic institutions now for a more diverse campus as part of the educational life of universities and colleges. So hopefully, for the next generation it won't be so hard. People ask me, did I encounter a lot of discrimination and so forth? And I did, to a certain extent when I was in grade school, when people would call you names that were very offensive, and so forth. But my parents told me to ignore that, and just keep your eyes on learning, and educating yourself, rather than spend a lot of time in a hostile mood, just because somebody calls you an inappropriate name.

Warren Washington with Tyler Prize co-recipient Michael Mann, a climatologist and geophysicist. (Photo: Joshua Yospyn)

CURWOOD: What gives you hope now, for our ability to deal with climate, to meet the climate challenge?

WASHINGTON: Well, I think the way it's happening now, you can see what's happening in the news. Almost every day, there's some weather or climate issue comes up. And there's a group of statisticians at Yale University that has been carefully taking polls of the public's attitude about climate change. And what is surprising is that 70% of the people agree that climate change is a serious issue, which is much higher than the representation in the Congress. But gradually, the Congress is coming around. I see that the Green New Deal didn't pass in the Congress, but that's just the first step. I see more steps of pushing for controls on fossil fuels by the states. There's real enthusiasm and success being shown as people switch from, you know, fossil fuels to other forms of energy production. And even on the science side and technology side, we're finally learning how to make good batteries, and better batteries using newer technologies. Eventually, we're going to win over, I think, to having a president that's going to really do something. So it may not happen in my lifetime. But it's coming.

CURWOOD: Warren Washington is a retired Senior Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and a winner of the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

WASHINGTON: Thank you for listening.

Related links:

- About the 2019 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement

- About Warren Washington

- Listen to LOE’s interview with Tyler Prize co-recipient Michael Mann

[MUSIC: John Williams, “Tango” on Dinner Classics: A Taste Of Spain, by Joaquin Turina, CBS Masterworks]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Delilah Bethel, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters, and Jolanda Omari, Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth