May 10, 2019

Air Date: May 10, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bipartisan House Vote For ‘Climate Action Now’

View the page for this story

The US House of Representatives has passed a landmark bipartisan bill in the fight against climate change. The Climate Action Now Act, H.R. 9, calls for President Trump to make a plan for how the U.S. will keep its commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement, and also prevents the President from using federal funds to pull the U.S. out of the agreement, as he has vowed to do. Three Republicans joined all present Democrats as affirmative votes for the final tally on May 2. Congressman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-NJ), Chair of the Committee on Energy and Commerce for the House, spoke with Host Steve Curwood about the Climate Action Now bill, and where the House plans to go from here. (06:31)

Climate-Resilient Cities

View the page for this story

As climate disruption advances with rising sea levels and more intense storms, floods and wildfires, some people are thinking about safer places to live. And cities like Duluth, Minnesota and Buffalo, New York are already branding themselves as climate resilient, thanks to factors such as their cool climate and proximity to bountiful fresh water. New York Times reporter Kendra Pierre-Louis joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss why these two cities are attractive to climate refugees, as well as the potential threat of climate gentrification. (07:00)

A Grave Biodiversity Warning

View the page for this story

The United Nations recently released a shocking report on the state of the world’s biodiversity, warning that about a million plant and animal species are on the verge of extinction due to human activity. Noah Greenwald, the Endangered Species Director for the Center for Biological Diversity, spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the grim outlook for biodiversity. (08:29)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Looking beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra talks with Host Steve Curwood about an unexpected wildlife killer of creatures big and small: trains. They then discuss rising tourism to the world’s melting glaciers, as well as the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, a nonprofit floating lab and classroom founded by Pete Seeger to preserve the Hudson River through education, advocacy, and—of course—musical celebration. (05:08)

Goldman Prizewinner Vanquishes Oil Terminal Project

View the page for this story

When the Tesoro-Savage oil terminal project threatened to bring polluted air and the risk of devastating oil spills to her hometown of Vancouver, Washington, community organizer Linda Garcia got right to work – and along with her neighbors, vanquished the project. Garcia’s efforts to protect her community and stand up to fossil fuel interests have been recognized with one of the prestigious 2019 Goldman Environmental Prizes. She joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how her community fought and won against Tesoro-Savage, and why even threats and harassment couldn’t silence her. (11:04)

Exploring The Parks: North Cascades National Park

View the page for this story

North Cascades National Park, just a three-hour drive from Seattle, is at the heart of one of Washington State’s most expansive wild ecosystems. It has more glaciers than Glacier National Park, yet North Cascades is one of the least visited parks in the United States. Saul Weisberg, founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute and super docent of the North Cascades, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about his years exploring the park. (08:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Linda Garcia, Noah Greenwald, Kendra Pierre-Louis, Frank Pallone, Saul Weisberg.

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The US House has passed its first major climate bill in a decade. It would start Climate Action Now and keep the US in the Paris climate agreement.

PALLONE: My greatest fear is that we just fall behind while everybody moves ahead. In other words, China, India, the European Union, they develop solar panels and wind turbines and, you know, they create all the jobs. While, you know, we're in the 19th century by encouraging fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: Also, a UN report estimates that roughly 1 million species could soon go extinct.

GREENWALD: We are in an extinction crisis; species are going extinct at roughly 1,000 times background rate. But we do still have time, there's plenty of nature left. We just need to take steps to protect it and we need to curb our global emissions of greenhouse gasses.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Bipartisan House Vote For ‘Climate Action Now’

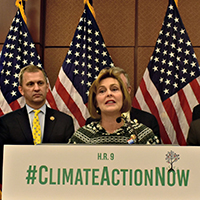

Florida Democratic Congresswoman Kathy Castor (center) introduced HR 9, Climate Action Now, on March 27, 2019. (Photo: House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The United States blocked an official joint communique of the eight nations of the Arctic Council on May 6th by opposing any mention of the dangers of climate change. In fact US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo told the Council he welcomes a warmer Arctic because “steady reductions in sea ice are opening new passageways and new opportunities for trade,” adding that “Arctic sea lanes could become the 21st century Suez and Panama Canals.” It’s all part of the Trump Administration’s efforts to deny the urgency of the climate crisis and its intention to back out of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. And though the Republican President and Senate majority continue to oppose climate action, the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives recently passed a bill called the Climate Action Now Act to keep the US in the Paris deal. Representative Frank Pallone Jr. of New Jersey is the Chair of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, and he joins me now -- welcome to Living on Earth!

PALLONE: Oh, thank you, Steve, glad to be on your show.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what was the driving force behind the Climate Action Now Act? What does it call for, exactly?

PALLONE: Well, basically two things. One is that no money will be spent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, which doesn't actually happen, or can't happen, I should say, until November of 2020. And then the second thing is to call upon the Trump administration to put together a plan to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Of course, all this is, by way of background, where the President has said that he wants to withdraw. And the President is repeatedly sabotaging any efforts that have been put in place by the federal government to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, you know, weakening the Clean Air Act, weakening the Clean Water Act, trying to get rid of fuel efficiency standards, you know, the list goes on.

The Paris Agreement was adopted within the United Nations in December of 2015, with 195 members signing onto it on Earth Day, 2016. The United States was represented by John Kerry, then Secretary of State. President Donald Trump has said he intends to withdraw the United States from the Agreement at the earliest possible moment, in 2020. (Photo: US Department of State, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Now, the Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell, has said he's not going to consider this bill. So what are the prospects that you could take the provision, especially prohibiting the administration from spending any resources on withdrawing from Paris, and put that on some sort of budget measure, something that the Senate would have to consider?

PALLONE: Well, of course, you can do that. It could be part of the appropriations bill. But you know, then it becomes part of the give-and-take as to what, you know, whether those appropriations bills pass, and whether there's a government shutdown. But sure, that could definitely be a bargaining chip in the process of the appropriation bills.

CURWOOD: And what's your position on that?

PALLONE: Well, I mean, that's fine. But I mean, you know, I assume that since McConnell and the Republican leadership in the Senate continue to be climate deniers, they're, you know, they're going to take the position that they don't support the Paris Agreement. But we'll see. You know, we have to do what we can in a bipartisan way, and then we have to try to push the Republicans a little further. So it can certainly be something that we say, look, this is important. And it'll be part of the appropriations process. That's certainly an option.

CURWOOD: Now, from your perspective, what is the importance of the United States staying in the Paris Climate Agreement?

PALLONE: My fear, Steve, is that, you know, every other country is moving towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. Now, it's voluntary, so there are various degrees, some are better than others. But we traditionally would take a leadership role in these things. And by taking a leadership role, not only is it more likely that the other countries follow the United States' lead, and so the Paris Agreement is successful in trying to, you know, cut back on greenhouse gases and climate change. But also, we're out front in terms of an innovation economy that, you know, tries to move that way and develops new technologies and jobs that improves our economy all along. My greatest fear is that we just fall behind while everybody moves ahead. In other words, China, India, the European Union, they develop solar panels and wind turbines, and you know, they create all the jobs and their economy moves forward through these innovations. While, you know, we're in the 19th century by encouraging fossil fuels. So it's both the health and safety aspects of trying to prevent climate change. And at the same time, trying to innovate and improve your economy towards the future, rather than, you know, looking at the past. And my fear is that we just fall behind and we become the outlier and we suffer the consequence.

Frank Pallone Jr. has served as US Representative as a Democrat for New Jersey’s 6th congressional district since 1988. He is the Chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. (Photo: US House of Representatives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Chairman Pallone, what's your top priority now as Chair of House Energy and Commerce?

PALLONE: Well, we are definitely moving forward with climate initiatives. We're hoping to do a major infrastructure bill in the next few months. And that's going to be a vehicle to do a number of initiatives. You know, for example, we had a hearing a couple weeks ago, on all the energy efficiency issues, you know, things like weatherization, improving buildings so they're more efficient, so you don't lose energy, you know, more efficient light bulbs, more efficient technology, that type of thing; weatherization. So those are the kinds of initiatives that we're going to hopefully include in our infrastructure bill, that would also cut back on greenhouse gases. And those are things we might get Republican support for.

CURWOOD: In terms of Republicans, on the Climate Action Now Act, you got three Republicans to come across the aisle; I remember back in the days of Waxman-Markey, it was a straight party line vote from the Democratic side.

PALLONE: You know, for eight years when Republicans were the majority on our committee, we weren't allowed to have any hearings or move any legislation that dealt with climate change. But as soon as we took the majority, we started having the hearings, the same Republicans were now saying, oh, we want to address climate change. We think it's important. And so what we're getting -- and this is why I think we might have some hope with this infrastructure bill -- they're not denying that climate change is human induced anymore. At least the leadership in our committee isn't saying that anymore. So there has been a change with some of the more moderate Republicans, that now they admit that climate change is human induced and needs to be addressed. So I am a little more optimistic. You know, McConnell probably won't take up, you know, H.R. 9 on the Paris Agreement. But if these things are included in an infrastructure bill, we may very well get some Republican support. They've changed in many ways, in what they articulate. We'll see what they actually do.

CURWOOD: Congressman Frank Pallone, Jr. represents New Jersey's sixth district and is Chair of the Committee on Energy and Commerce in the House. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PALLONE: Thank you, Steve. Take care.

Related links:

- Reuters | “House Backs Paris Agreement in First Climate Bill in a Decade”

- House Committee on Energy & Commerce | “E&C Chairman Pallone on House Passage of the Climate Action Now Act to Keep the U.S. in the Paris Agreement”

- H.R. 9, or the “Climate Action Now Act”

- Listen to our previous interview with Rep. Kathy Castor (D-FL) about HR 9 here

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “The Raven” on Soul Brother Cool, WJ3 Records]

Climate-Resilient Cities

Investing in climate migration could potentially create more jobs for the city of Duluth, Minnesota. (Photo: Jim Brekke, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND-2.0)

CURWOOD: As climate disruption advances with rising sea levels, more intense storms, floods and wildfires, some people are thinking about safer places to live. And cities including Duluth, Minnesota and Buffalo, New York are already branding themselves as climate resilient. Here to tell us more is New York Times reporter Kendra Pierre-Louis, who recently wrote about this trend. Thanks for joining us Kendra!

PIERRE-LOUIS: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what exactly are the criteria of being a good climate refuge city?

PIERRE-LOUIS: It's an abundance of water, because water is life. It is a location that is not going to be too hot or too cold as the climate warms. It's a location that has fewer of the worst negative impacts of climate change. So they're not going to be affected by sea level rise, you're not going to get slammed by a hurricane, they're not necessarily going to burn to the ground because of a wildfire. And they're an area where an economy can thrive. So they're somehow connected to an economic hub.

CURWOOD: So, why are these two cities model cities for climate refuge?

PIERRE-LOUIS: Buffalo and Duluth actually share a lot in common. So they're both on a great lake, which means they have a ready supply of fresh water. They're relatively cool places. So, as the climate warms up, they'll still be really comfortable places to live, especially in summer. I think Buffalo's never had a 100-degree day. They are near major metropolitan cities; in the case of Buffalo, it's Toronto, in the case of Duluth, it's the Twin Cities. And those larger metropolises are expected to fare relatively well under a warming climate, so they will have that economic anchor to tie them to. And both cities actually have a footprint that is larger than the number of people that live there, so there is room for growth.

CURWOOD: What other cities around North America do you think would meet this criteria?

PIERRE-LOUIS: Generally, a lot of the places along the Great Lakes are better places to retreat to. The thing, though, that you have to keep in mind is that nowhere on earth is safe from climate change. And so even Duluth, even Buffalo are dealing with the effects of climate change. Duluth has had serious flooding issues, they've had really big storms. But these are issues that are more readily or more able to mitigate against, right, like it's much harder to protect against rising seas, or hurricanes. It's easier, to a certain degree, to protect against flooding. And so these are cities that are not safe from climate change. It's just that the impacts of climate change are expected to be less bad, and we’re better able to protect against them.

Duluth Minnesota has cold temperatures and access to the fresh water of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes, which alone contains 10% of the world's surface fresh water. That makes it less vulnerable to heat waves and drought. (Photo: Glen Dahlam, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say that these places would give someone moving there maybe a bit more time than they would have elsewhere?

PIERRE-LOUIS: Yeah, I think that's a fair thing to say. Something else that one of the researchers I talked to raised, somewhat interestingly, is that both Minnesota and New York State are high-tax states, that means that these cities have a base from which to draw upon to actually do the adaptation and mitigation. So when you're looking at places that don't have as much money in terms of state income tax, or property taxes, even, you're having the same effects, but you don't necessarily have the ability to mitigate or adapt against it, absent federal dollars. And so that's just something else that I'm starting to think about really critically and to keep in mind. It's not just that these places are really geographically well-suited for a warming world, it's also that their social systems are designed in such a way that they're able to actually take action against it. And I saw that a lot in Duluth. Duluth has actually done a lot of climate change adaptation and mitigation work.

CURWOOD: Now, what signs are there that other cities are, in fact, looking into marketing themselves as places of climate refuge as well?

PIERRE-LOUIS: These are the two that are the strongest that have gone on record in one way or another as saying it, really boldly, that this is a thing that they're thinking about. But as I touch on in the piece, nobody really knows if it's going to work, especially in the case of Duluth, just because of how we know existing patterns of migration are. Over the past hundred years, for the most part, everyone in the United States has been migrating south, not north. The one exception is obviously the Great Migration. And that was people fleeing from Jim Crow, that was people fleeing from really horrible racism, from being lynched. It was a matter of immediate survival. And as soon as the United States government started passing legislation, like the Voter Rights Act, or the Civil Rights Act, that migration started flipping. There's been a really slow reverse migration of African Americans from the North into the South since the 1970s. And the other way that we tend to move is through social networks. So if you have a cousin or an aunt or an uncle who lives some place, and where you're living is like not that great, you might decide to move to where that extended family member is or where a friend network is, and you know you can get work. So in that regard, Buffalo is actually better positioned than Duluth because Duluth is pretty homogenous. Most of the people in Duluth are from the area, more or less, where Buffalo has really doubled down on immigration. You know, we've heard stories in Buffalo of a recycling center where they actually need a translator to hold meetings, because so many people speak so many different languages. And after Hurricane Maria, Buffalo got 10,000 people, which is huge for a city of about 250,000 people. And that's because Buffalo has this long history of having a large Puerto Rican population relative to the size of its city. Part of the reason some of the Puerto Ricans moved to Buffalo, is Buffalo had actually been advertising on Puerto Rican TV for years for teachers, they were looking for Spanish language teachers. And so people understood that Buffalo existed and was a place that they could move to and possibly find work. And I think even this conversation, even the article, in a weird way, kind of feeds into people's awareness of these cities and of these places. So sometimes those connections don't necessarily have to be super strong. It just has to be people have to be aware that those places exist and are an option.

Buffalo City Hall Observation Deck overlooks Lake Erie. Buffalo’s Mayor Byron W. Brom has been advocating for the city to become a climate refugee hub. (Photo: Andy Nystrom, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what about this concept of climate gentrification? What is this concern? And how does it come into play with cities such as Duluth and Buffalo?

PIERRE-LOUIS: That is an absolute concern, which is the idea that as people who have choice and preference, so people with money, move to avoid the worst effects of climate change, they push out people who are living in places that are relatively safe from climate change, and push those populations into riskier areas. It's less of a concern in Buffalo in a sense because Buffalo has a lot of empty housing stock still. So you could actually get a decent number of people into Buffalo before housing prices would go up significantly. In the case of a city like Duluth, this is a particular concern, because even though Duluth's footprint as a city is very large, they actually don't have a ton of excess housing. So if a lot of people were to move in before they built housing to accommodate them, there's a real risk it would cause housing prices to increase.

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a Climate Desk Reporter for The New York Times. (Photo: Courtesy of The New York Times)

CURWOOD: So Kendra, how often are you looking at the classified housing ads in Buffalo, New York?

PIERRE-LOUIS: [LAUGHS] Well, not too often because housing in Buffalo is so much cheaper than housing in New York City that it makes me really depressed. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Kendra Pierre-Louis is a reporter with The New York Times. Kendra, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PIERRE-LOUIS: No worries. Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: And, you can tell me. Are you really packing for Buffalo or not?

PIERRE-LOUIS: [LAUGHS] I am not.

Related links:

- New York Times | “Want to Escape Global Warming? These Cities Promise Cool Relief”

- The Buffalo News | “How to Escape Climate Change? Move to Buffalo, One Expert Says.”

- Duluth News Tribune | “Duluth as a Destination for Climate Refugees?”

[MUSIC: David Grisman Quintet, “Why Did the Mouse Marry the Elephant?” on Dawngation, by David Grisman, Acoustic Disc]

CURWOOD: Coming up - news from the frontlines of the battle for Nature’s survival. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Grisman Quintet, “Dawgnation” on Dawgnation, by David Grisman, Acoustic Disc]

A Grave Biodiversity Warning

Tropical Deforestation opened the door for invasive species and lessens the huge carbon sequestration potential that forests provide. This is a photograph of an oil palm plantation in the forest of the Sentabai Village of West Kalimantan. (Photo: Nanang Sujana, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The United Nations recently released a shocking report on the state of the world’s biodiversity. The UN scientists warn that roughly 1 million plant and animal species are on the verge of extinction due to human activity. It would be the first mass extinction since humans started walking the earth and has dire implications for the survival of our own species. Already humans are losing key ecosystem services that nature provides, including crop pollination, storm mitigation, and clean air and water. Noah Greenwald is the Endangered Species Director for the Center for Biological Diversity, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So what went into putting this study together?

GREENWALD: Well, so this is a UN study, and the intent of it was to be, you know, similar in scope to the IPCC reports on climate change. You know, so it's hundreds of scientists from around the globe coming together and compiling information on species extinctions and loss of habitat. And the UN wants to bring this issue to the forefront, in the same way that climate change has been brought to the forefront with those IPCC reports.

BASCOMB: Well, the headline being reported is that 1 million species are at risk of extinction. How did researchers arrive at that number?

GREENWALD: They got at that number by looking at the amount of diversity in different areas, the amount of habitat that's been lost, and the amount of habitat that's projected to be lost. It's an estimate, looking at threats and looking at what we know about species already.

BASCOMB: And what is the timeframe for this mass extinction?

GREENWALD: You know, for many of these species it's in the next just few decades. If we don't take action soon, say, the next 10 to 20 years, our ability to reverse these trends gets smaller and smaller. So it's, like with climate change, this is something we need to take action on right away.

BASCOMB: So climate change, and this biodiversity loss, they're really interrelated. I gather it's hard to separate one from the other.

GREENWALD: Very much so. I mean, in part because climate change, one of the biggest impacts from it is going to be species loss. And you know, we're already losing so many species because of our footprint, because of altered habitats. It makes it even harder for species to adapt to climate change because their ability to move is impacted by habitat loss and fragmentation.

BASCOMB: And then climate change, I would think, would make what habitat is left less suitable for them. If it's too warm, if it's too wet, if it's too dry, however the climate may be changing locally.

GREENWALD: Yeah, exactly. I mean, even things like the climate for plants, the climate might still be right, but it may no longer be right for their pollinators. So you can get things that become out of sync, essentially.

BASCOMB: And what are the other factors that are leading to this mass extinction?

GREENWALD: It's, you know, the same factors that we've been seeing in species conservation for a long time: habitat destruction, invasive species, pollution, exploitation. You know, so something particularly in the oceans these days for fisheries, you know, there's, I think the report concluded that a third of all fisheries are unsustainable. Poaching for species like elephants, or rhinos or lions, those -- direct exploitation becomes a serious problem as well.

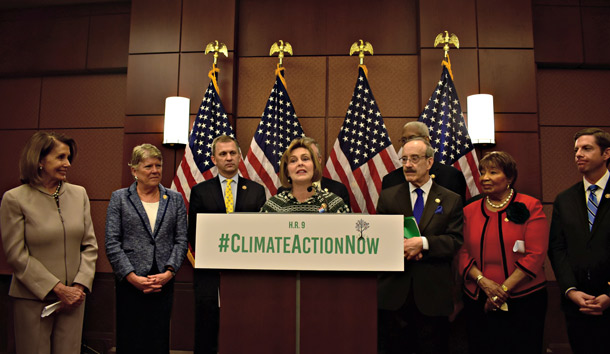

Coral Reefs harbor one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet as well as supporting fisheries, tourism and the overall health of the ocean. (Photo: Jim Maragos, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr, C BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, let's just look at a few examples of the different habitats that are being threatened and what they mean. What about the rainforest? I mean, tropical rainforests are arguably the most biologically diverse habitat on our planet. What does this report say about rainforests and the species that are at risk within them?

GREENWALD: I mean, it's true, tropical rain forests just hold an incredible diversity of species. And so their loss has a much greater impact on overall biodiversity loss. You know, we've known this for decades. And you know, efforts have been made to slow tropical forest deforestation. But it's, it's still ongoing, you know, the conversion to palm plantations in Indonesia has been one of the most striking examples in recent years, but there's others as well. And so we have to figure out a way to help these countries not destroy their forests and protect their forests. It's critically important for biodiversity. It's also critically important for climate too, because these forests, you know, help regulate our climate and store massive amounts of carbon. You know, closer to home here in North America, the extinction crisis is really happening, the leading edge of it is, our freshwater ecosystems, our rivers and streams. That's where the most species have been lost. We're at risk of losing many fish, mussels, crayfish, we've been working to get these species protected under the Endangered Species Act because of that.

BASCOMB: And what about coral reefs? I know that they're in really sharp decline all over the world. What's going on there in terms of possible species extinctions?

GREENWALD: So coral reefs are just hugely important to diversity in the oceans, you know, that's where most of the biodiversity is found, particularly in tropical waters. And, you know, overall, it's the near-shore habitats, you know, whether you're tropical or non-tropical, that have most of the species in the ocean. And that's also, of course, where we're having the most impact. And the report highlighted that a third of them have died since, I think it was 1970. I actually witnessed this personally, I was in a class in 1990, on the natural history of Hawaii, and spent a month at a campground in Maui, and there was a beautiful, beautiful reef there. It was amazing, just teeming with life. And I went back there for spring break this year, to Maui, and stayed at the same campground and, you know, observed, largely, a dead reef where they're had once been this incredibly live, you know, beautiful reef.

Noah Greenwald is the Endangered Species Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. (Photo: Courtesy of Noah Greenwald)

BASCOMB: Of course, human beings do not exist in a bubble. How might this loss of biodiversity affect people?

GREENWALD: Yeah, so I think the report did a really good job of highlighting why this matters to us. And that gets back to this concept of ecosystem services, so ecosystems do things for us. Most of our medicines come from species and from ecosystems; all of our food; ecosystems clean our water, they clean our air, they moderate floods, they moderate our climate. We need ecosystems for our quality of life and for our very own survival. And ecosystems are made up of species. It's, the parts of ecosystem are species. And so as you lose more and more species, the ability of ecosystems to function and provide these services becomes compromised. You know, an analogy that's often used is, say, like an airplane or a helicopter, you know, you can maybe lose a couple bolts here and there, and the plane will still fly. But as you lose more and more parts, you're going to eventually drop from the sky. And that's the concern, that we're going to lose these ecosystem services, which provide so much benefit to us.

BASCOMB: Well, this is all thoroughly depressing. And the scale of the problem just feels overwhelming. What can you say to someone listening right now that thinks the world's going to hell in a handbasket? I mean, what can possibly be done? What can I do?

GREENWALD: Yeah, I mean, I think it's important to remember that there's a lot of nature and the natural world that's left. And so there's a lot to protect, and we have, we still have a beautiful world. And we just need to work harder to protect it. We have to let those in power know that this is critically important to us, and that we need change. We need a fundamental transformation in how we do business, you know, both to address loss of biodiversity and to address climate change.

CURWOOD: Noah Greenwald of the Center for Biological Diversity, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- UN News | “The World is ‘on notice’ as major UN report shows one million species face extinction”

- New York Times | “Humans are Speeding Extinction and Altering the Natural World at an ‘Unprecedented’ Pace”

- IPBES | “Media Release: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’ ”

- Center for Biological Diversity | “Endangered Species”

[MUSIC: Kavita Shah, “Paper Planes” on Visions, by Thomas Wesley Pentz/Joe Strummer/Paul Simonon/Mick Jones/Topper Headonen & Mathangi Arulpragasam/arr. Kavita Shah, Inner Circle Music]

Beyond The Headlines

Untold numbers of animals, both big and small, from elephants to frogs, are killed on railroad tracks each year. One proposed solution is to play predator sounds near tracks. (Photo: Timothy Vogel, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a peek behind the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia; hi there, Peter. How are you doing?

DYKSTRA: Well, I've been working through a little cold, but bear with me. We've got some interesting things to talk about. Starting with railway collisions with wildlife, from elephants to grizzly bears to even small frogs that are too fat to jump over the rails, we're beginning to understand how big the problem is. One little fact in a field that doesn't really have many numbers attached to it yet: over the last 30 years on Indian railways alone, 220 elephants have been struck and killed by trains.

CURWOOD: So that means almost an elephant every month or two gets killed by a train there.

DYKSTRA: Right. Those have to be pretty messy collisions, in addition to impacting a population that doesn't need any more negatives.

CURWOOD: So of course, a railway creates an edge habitat, right? I mean, whenever the rail line went up, there's this little area that's right next to it that goes, you know, way back in the day and animals like.

DYKSTRA: A lot of animals love it, including deer, the main source of car collisions in this country and in a lot of other places. That edge habitat, where sunny areas meet the forest, is a great place for a lot of predators to find food. It's also a great place for plant-eaters to find food, and every railway is edge habitat.

CURWOOD: So what's to be done? I mean, we just heard about the precipitous decline in wildlife thanks to development and climate disruption. There must be something that could be done.

DYKSTRA: They’re trying a few things in a few places around the world. There are recordings of predator noises being played near railroad tracks, hopefully to scare away animals that might fear being eaten more than they fear being hit by a train. Airports in a lot of places use sound cannons, little blasts to scare away Canadian geese and other animals that could tend to get stuck in jet engines. We don't know how big the problem is. We're beginning to get a grip on it. And solutions need to come soon, because it's potentially a major impact on wildlife.

As glaciers melt, tourists flock to see the icefields before they’re gone. Pictured here is Alaska’s LeConte Glacier expanse, which—like so many glaciers around the world—is disappearing. (Photo: Carey Case, US Forest Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's an unusual increase in tourism: people flocking to see melting glaciers before the glaciers are entirely melted away. There's a big boom in Montana in Glacier National Park where many of the glaciers are already gone and the rest are going quickly. Places like Kilimanjaro; the Alps; folks are going out to see something that may not be there for long. I kind of did the same thing with my kids back in 2005. On a trip to New Orleans, I took them out to Grand Isle, the one beach town left in southern Louisiana, because I wanted to have them see a place that would be doomed by hurricanes. The irony is that Grand Isle is still there, and a lot of New Orleans disappeared six months later. It's kind of a reverse bucket list. Instead of seeing a place before you die, you see a place before it dies.

CURWOOD: Indeed, if we keep going the way we are, there are going to be a lot of places like that.

DYKSTRA: Right, there's a double-edged sword with the glacier tourism, though. There's more business, there's more climate change awareness when people go out to see vanishing glaciers. But at the same time, if you're increasing plane travel, or car or bus travel, just to see the glaciers, you're actually contributing to their death.

CURWOOD: If you're putting more carbon into the atmosphere, certainly. Alright, it's time for us to take a look back in the annals of history and -- tell me what you see.

Musician and activist Pete Seeger (with guitar) founded Hudson River Sloop Clearwater in 1969. The nonprofit is named after a 106-foot long replica of a historic sloop (a kind of boat that sailed the Hudson in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) that sailed the Hudson in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Today, the Clearwater organization uses education, advocacy, and music to promote conservation and sustainability. (Photo: Pete Seeger, “Turn, Turn, Turn,” Jim, the Photographer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: A 50th anniversary of note: Pete Seeger and some other volunteers launched the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater on May 17th, 1969. And for 50 years, the Clearwater has sailed up and down the Hudson River, other waterways and ports along the Northeastern US. It's a floating lab and a floating classroom on saving waterways. And it's been a symbol of the great comeback of the Hudson River for the past half century.

CURWOOD: But all is not well with the Hudson River yet though, is it?

DYKSTRA: No the PCB dumping that was the Hudson's biggest problem still isn’t resolved and believe it or not, the EPA just gave a pass to General Electric, PCB dumper back to the 1940s and earlier, to not continue with their cleanup. It's a setback. It's proof that not only does the Clearwater have more work to do, but other organizations it helped to spawn, like the Riverkeeper. The first Riverkeeper was started by a Clearwater crew member named John Cronin and also Bobby Kennedy, Jr. There are now Riverkeeper and Baykeeper chapters all over America and all over the world.

CURWOOD: This sounds largely like a success story, Peter. Thank you for reminding us of that. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on our website, loe.org.

[MUSIC: Pete Seeger, “Sailing Down My Golden River”]

Related links:

- The Revelator | “Death by Rail: What We’re Finally Learning About Preventing Wildlife-train Collisions”

- The Daily Climate | “People are flocking to see melting glaciers before they're gone—bringing both benefit and harm”

- Clearwater

CURWOOD: Coming up – A US national park with 300 glaciers that almost no one has heard of. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Don’t go away!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Afro-Cuban All Stars, “A Toda Cuba Le Gusta” on A Toda Cuba Le Gusta, by Remberto Becquer/arr.Juan de Marcos-Gonzalez, World Circuit/Nonesuch]

Goldman Prizewinner Vanquishes Oil Terminal Project

Linda Garcia near the Port of Vancouver, in Washington state. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Each spring, we look forward to hearing the stories of courageous activists who win the Goldman Environmental Prize. Its recipients are from every corner of the world. Today we bring you the story of Linda Garcia, a community organizer and activist. When a major export terminal project threatened to bring 360,000 gallons of crude oil per day through the Fruit Valley neighborhood of Vancouver, Washington along the Columbia River, Linda Garcia led a long fight against the project. She and her fellow activists finally celebrated the cancellation of the Tesoro-Savage project in 2018, when Washington Governor Jay Inslee rejected its permit. Linda Garcia joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, and congratulations!

GARCIA: Thank you, Steve. I appreciate it.

CURWOOD: So how does it feel to have fought and won against this oil terminal project?

GARCIA: Amazing. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Bet it does, yeah!

GARCIA: Yeah, I don't think any of us really anticipated the win. It's wonderful knowing that we did win one of the battles in the ultimate war.

CURWOOD: What do you mean, you didn't anticipate winning?

GARCIA: I think going into it, we recognized that a company that was, was trying to come into our community had a lot more power and a lot more resource, and a whole lot more money than what we did. But we ended up having people power. And we proved to them that that's the most important piece. It's not about the money. It's not about the profit, it's about people caring for each other.

CURWOOD: So what was the Tesoro-Savage Project trying to do with a new oil terminal facility in Vancouver, Washington; and why there, in particular?

GARCIA: Vancouver still has some room at their port, at the Port of Vancouver. And their goal was to bring in an oil by rail export terminal, and they were going to be bringing in unit cars filled with Bakken crude oil, both from the tar sands in Alberta, Canada, and the fields from South Dakota. And they were going to be bringing in multiple unit trains. One unit train is about 144 oil tank cars, train cars, and it's about a mile and a half long, and we were looking at between five and eight of those per day. And with each unit train comes more danger.

Linda Garcia meeting with a community member while door-to-door organizing against the Tesoro-Savage oil terminal project. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Yeah, let's talk about that. I mean, of course, there's always a catastrophic situation like a ginormous spill or derailment, but what would the day to day impacts of this project have been?

GARCIA: For me, specifically, and those in the Fruit Valley neighborhood immediate, the Port of Vancouver sits within the Fruit Valley neighborhood boundary. And for us, it was more about the air quality. The moment that that terminal would have gone online, every single second of every single day, there would have been VOCs, volatile organic compounds, emitted that pose great health risks and hazards, from asthma-causing chemicals to cancer-causing chemicals. And so for the majority of us in the beginning, it was about the air quality. And then as the battle kept going on, we started seeing more and more oil train derailments and explosions going along with that. The Lac-Mégantic in Canada, that was the largest one as far as oil by rail disasters. And then, just a few short months before the final decision was made, we had a derailment just about 40 miles east of us in Mosier, Oregon. That was tragic, and it brought the reality of that entire situation and the possibility of that happening so much closer to home. It was on the news 24-7, so it wasn't something that we could escape and pretend wasn't happening anymore. We couldn't say, "Oh, it's far away from home, that will that will never happen here." We saw that it could.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the stakeholders there. Among other things, you're in Fruit Valley; that must mean that you grow a lot of stuff that folks all over the United States must eat.

GARCIA: Fruit Valley was once known as the prune capital of the world. Back in the day, that was the place that prunes were grown and exported. Now, there aren't prunes, but there are still several home farms. The Earth is very fertile there; growing is almost year-round for many fruits and vegetables. So to have that blend of industry at the Port of Vancouver, it was a work, and we always worked well together, Fruit Valley has always worked well together with the Port of Vancouver and had a great working relationship. So we could continue with the farming. Obviously, with more and more development coming, we've lost some of our farmland down there. But there are some farmers still going strong.

CURWOOD: And tell me who's, who's there in terms of people? Who lives in this, this area?

GARCIA: Fruit Valley is a, it's a very diverse community, from socioeconomic, to racial and cultural. It's kind of like a very small, close-knit big city. [LAUGHS] That probably makes no sense. But there are so many people with so many differences, but we're close; we take care of each other, we protect each other. I think that's how everything started. We recognized the need to be there for those that maybe couldn't stand up for themselves in the moment.

The six 2019 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients participated in a ceremony on Friday, April 26th. From left: Belén Curamil Canio of Chile (on behalf of her father, Goldman recipient Alberto Curamil); Jacqueline Evans of the Cook Islands; Alfred Brownell of Liberia; Linda Garcia of Vancouver, Washington; Bayarjargal Agvaantseren of Mongolia; and Ana Colovic Lesoska of North Macedonia. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Well, tell me, how did you build this coalition?

GARCIA: Um, it started mainly as other organizations coming in and helping, environmental organizations. Then we started getting some strong opposition to the terminal, which meant support for our group from unions; some local politicians stepped up to the fight. And so it was kind of a, an overall community organization coming together. As far as other communities locally, we have the tribal nations coming in; their livelihood depends on that river. And anything that could have gone wrong would have directly impacted and affected the river and the inhabitants that live from it and work from it. After the Mosier incident, we had the mayor of Mosier come down and begin testifying at the port. And before city council, and talking to the politicians in the local area there as well. We had communities upriver and downriver, from Idaho, Canada, Eastern Washington, Oregon, even California, coming in and sharing their stories of what their communities looked like, before, during, and -- if anything similar to the project that we were looking at being proposed -- what it looked like after as well. Anything that we heard from them, I guess we, we multiplied it by, you know, infinite number because this was proposed to be North America's largest oil by rail terminal.

CURWOOD: Now, why you? Why was it important for Linda Garcia to fight this oil terminal?

GARCIA: Um, I mean, there's so many answers to that one. Um, I think it's, it's just because it was the right thing to do. I, I didn't feel comfortable not doing anything. And there were so many voices of so many people who were afraid to speak up, or they didn't have the time to get out there and do it, and go to all of the meetings and testify; they were scared to do that. I was scared to do that, but I just kept pushing through because I -- it's more than idealism. It depends on people stepping up, and making sure that corporations and government entities don't try and pull the rug out from under us, they don't try and blindside us with decisions that they think are best for us. Instead of coming in and speaking at us, talking at us, they needed to listen, and they weren't doing that. And so for me, I needed them to hear us. It wasn't just, "I would like you to sit and listen." It was, "I need you to hear what we're yelling at you. We started with small voices, and we're large and we're loud, and you need to hear what we're saying." Because this is about our lives. It's about our livelihood, our sustainability, our connectedness, our vitality. It didn't feel right in my heart to stop. And so I just listened to my heart and just kept going.

CURWOOD: Linda, to what extent did you get hassled, threatened, confronted in inappropriate ways about your activism here?

GARCIA: I started receiving threats via phone in 2015. And it was every now and again, it wasn't constant. Recently, because I continue my work, it has escalated and has turned into things like my home being broken into multiple times; being assaulted, threatened; every possible thing you could think of; it's, it's not pleasant. It's terrifying. They need to know that that can't happen. And I'm not stopping.

CURWOOD: So fossil fuel companies are still trying to export their products abroad, especially as this country is getting off of coal and reducing the use of oil. How vigilant do you think your community and other port towns need to be about future proposals similar to the Tesoro-Savage one for the oil terminal?

Linda Garcia with her Goldman Environmental Prize Ouroboros sculpture. In addition to a monetary prize, Goldman Prize winners each receive this bronze sculpture. Common to many cultures around the world, the Ouroboros, which depicts a serpent biting its tail, is a symbol of nature’s power of renewal. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

GARCIA: Very vigilant. They need to keep in mind that the false promise of jobs everywhere is exactly that. It's kind of a fallback that they tend to use, they find the weak point and go for that. And obviously post-recession, the weak point is employment, and finding those jobs. In that vigilance needs to come the idea, the vision that there are clean jobs and green jobs. And that doesn't just mean environmentally, that means, you know, that can be over healthcare and IT and education and high tech. There are places and spaces for that. But most organizations and politicos don't look at that. They don't see the larger, greater picture. They see an old model, and while most of us can understand and see that those old models aren't necessarily working, it's, now it's a matter of trying to, to push them forward and see the progressive ideal that there are different arenas that we can look at. We don't have to fall back and rely on the old commodities, the dirty, dangerous commodities, that there are newer things out there. And the fight continues. We look now to get policy into place so that newer infrastructure for these commodities can't be built.

CURWOOD: Linda Garcia is an organizer with the Washington Environmental Council, and the recipient of this year's North American Goldman Environmental Prize. Again, congratulations, Linda.

GARCIA: Thank you so very much. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- About Linda Garcia, 2019 Goldman Prize Recipient – North America

- Watch: Linda Garcia’s Goldman story

Exploring The Parks: North Cascades National Park

The sun breaks through early morning clouds near Easy Pass and Fisher Basin. (Photo: National Park Service, Public Domain)

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]

CURWOOD: As part of our occasional series on US public lands, this week we bring you a national park from Washington State: The North Cascades.

[SFX BIRDS AND OWL]

CURWOOD: An owl joins a chorus of other birds at Big Beaver Valley in the northern end of the park. The North Cascades is one of the least visited of the US National Parks. Perhaps names like Mount Fury, Poltergeist Pinnacle, and Forbidden Peak keep the crowds at bay. But despite its name, the beauty of Desolation Peak has captured many hearts, including that of the beat poet Jack Kerouac and more recently, Saul Weisberg, founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute. He joins us now from Bellingham, Washington. Saul, welcome to Living on Earth!

WEISBERG: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So for someone who's never been to North Cascades National Park, how would you describe it?

WEISBERG: Well, tucked away in northwest Washington is this amazing place of jagged mountains, glaciers, mighty rivers, big trees, incredible wildflower meadows. It's just, it's a special place. It's what the Northwest used to look like: big cedar, hemlock, Douglas-fir forests. And there's not a lot of it left and some of the best of it's left inside of, deep inside of North Cascades National Park.

CURWOOD: So the North Cascades National Park is one of only three national parks in the United States that we share some territory with Canada. There's Voyageurs, which is up in the Boundary Waters area there in Minnesota, there's Glacier National Park, and North Cascades. What makes North Cascades different from those parks?

WEISBERG: Well, one of the things that's unique about the park is that it's in the midst of this huge, wild ecosystem. And that ecosystem stretches, in northwestern Washington, it covers about 70 miles east to west long the Canadian border. The ecosystem is about 13 million acres, 7 million of the acres of that are protected public lands on both sides of the border: North Cascades National Park, three national forests, and then provincial parks in BC. And the park itself is only about six or 700,000 acres, but it's really the heart of that wild ecosystem. So it's the largest area of protected public lands across the whole US-Canada border. Very few roads go into the park itself. You have to get off on the trail, you have to climb or canoe the rivers to really get into that. And some people, climbers in particular, will access the park coming in from the north, driving around, and then hiking in through British Columbia.

Thirty years after discovering the park, Saul Weisberg still loves the North Cascades. (Photo: Courtesy of North Cascades Institute)

CURWOOD: As I understand it, North Cascades is one of the least visited of our national parks. Why do you suppose not so many people come to North Cascades?

WEISBERG: Well, part of it's the obvious answer that it's more remote. It takes more time to get to. When you're in downtown Seattle, you can see Mount Rainier and you can see the Olympics across Puget Sound. You don't see the North Cascades until you get north. And I've had people tell me well, North Cascades, that's somewhere up near Alaska, isn't it? And these are folks in Seattle who could get there in three hours. That's part of it. The other part of the low visitation is sort of an artifact of boundaries. The park complex itself is made up of the National Park, Ross Lake National Recreation Area, and the Lake Chelan recreation area. And most of the visitors are in those two recreation areas, which hug the lakes and the one highway that crosses the range. And to get in the park, you've got to get off that road. And I think there's still only, aside from the main highway, I think there's only six miles of paved road in the park. I could have that wrong, but it means that you've got to work to get into the park itself.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, when it comes to glaciers, of course, Glacier National Park is famous for glaciers, but the North Cascades, I gather -- you know, you have more.

WEISBERG: A lot more. Yeah. Over 300 active glaciers. Like all the glaciers, they're shrinking, some more rapidly than others. I was a climbing ranger in the park from 1979 to 1986, and you can see the difference pretty much everywhere you look. By late summer, areas that were glaciated now have just summer snowpack. There's areas where, in the early to mid 80s, where we would go into someplace and we would find, instead of a glacier, we would find a valley with a lake in it. And so it's been happening for a while, but it's really been accelerating recently. And we've seen the same thing in terms of wildlife where marmots and pikas are going up in elevation. And at some point those species, as the glaciers leave and the climate warms, essentially fall off the top of the mountains; they, there's no place for them to go because they are dependent upon snowpack for their livelihood.

Desolation Peak Lookout with Mt. Hozomeen in the background. (Photo: Pete Hoffman, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about your favorite places in the park. You're a climber, so I imagine there's some really steep mountains. But, but tell me, what are, what are your favorite parts there?

WEISBERG: I've never been to a place that didn't speak to me in some way if I spent enough time there. But I must admit that the Picket Range, which is some of the most rugged, most alpine, steep, scariest part of the mountains is a particular favorite. It's one of those places where you'd plot your route, usually spend a day or two just hiking to get up into the mountains. So you'd be hiking up deep, low-elevation valleys. And then you'd camp and you'd be looking at the route ahead through binoculars and just go, there's no way. It looks like, it looks like you're looking at the Gates of Mordor. And I just love that, a wilderness that is that wild and makes you feel that small.

CURWOOD: Well, the North Cascades National Park has some pretty foreboding names to it. You've got Desolation, Despair, Fury; what's with all the doom and gloom?

WEISBERG: Yeah, and you left out Torment and a few others. It shows you how the early white settlers and miners and trappers saw the place. For the native peoples it was home. But to the people who came in there and overwintered for the first time, it was a foreboding place. The days are short; in the valleys you might never see direct sunlight in the winter, because it's just creeping along behind the mountains. And it's cold. And there's a tremendous amount of rainfall. And so it just wasn't a happy place for folks who hadn't lived there for a long time. And it's interesting because a place like Desolation Peak, which is very hard to access most of the year when there's a lot of snow there -- in the summer, it's a beautiful, open, gorgeous forest with lush meadows of wildflowers, I mean, it's a heavenly place to camp.

Mount Shuksan and Picture Lake at North Cascades National Park. (Photo: jeffhollett, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, Jack Kerouac famously spent a couple of months camped out at Desolation Peak, calling the landscape one of the most beautiful he'd ever seen. Now you yourself have studied Kerouac and other poets, Beat poets, nature poets. In fact, you do poetry yourself. So how does poetry help you connect to the park?

WEISBERG: Poetry is how I slow down and pay attention. So when I'm hiking, I've always got a small notebook in my pocket, and I'm just jotting down an image or a thought. I call them field notes. And then gradually, over time, they kind of build and some build themselves into poems, and some never do. But it's, I often find myself, when I'm out, looking out either at a spectacular landscape, or maybe deep in the forest, just watching the raindrops cling to the branches and listen to the nuthatches in the trees. But it slows me down and makes me feel that I'm there.

CURWOOD: Saul, to wrap things up, we'd love to hear one of your poems from your collection. It's called "Headwaters." Please, if you could read that for us now.

WEISBERG: "Headwaters." With cupped hands, I bow and drink / Each day, a different stream / Many times from the same river / And once, the sea.

CURWOOD: Well, we certainly are all connected, aren't we? Saul Weisberg is founder and executive director of the North Cascades Institute, and perhaps you could call him the super docent of North Cascades National Park. Saul, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

WEISBERG: Well, thank you. It's been a pleasure to talk about one of my favorite places.

Related links:

- North Cascades Institute homepage

- National Geographic | “Venture into the Wild ‘American Alps’”

- New York Times | “Climbing a Peak That Stirred Kerouac”

- Saul Weisberg’s bio

[MUSIC: Herb Ellis, “America the Beautiful” on Texas Swings, by Samuel A. Ward/Katherine Lee Bates, Justice Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters and Jolanda Omari. And we say good bye this week to Delilah Bethel, thanks for all your help and sharing your popcorn! Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, iTunes and Google play. And like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth