July 19, 2019

Air Date: July 19, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Fracking and Your Health

View the page for this story

Fracking forces water, sand and chemicals into shale rock at high pressures, extracting much more oil and gas than conventional wells. But this highly efficient method comes with environmental and health risks including birth defects, cancer, and asthma. A new meta study brings together the findings of more than 1700 studies, articles and reports on the health impacts of fracking. Coauthor Sandra Steingraber, a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the importance of this massive body of evidence. (09:26)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra and Bobby Bascomb look at the Navajo and other Native American tribes’ shift from fossil fuels to solar energy. Then, they talk about Germany’s plans to reduce dependence on coal mining without sending miners to the unemployment lines. Finally, the pair look back on a couple of post-apocalyptic movies that incorporated environmental themes. (05:12)

Exploring the Parks: Petrified Forest National Park

View the page for this story

Living on Earth’s series on US public lands takes a trip to Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona where visitors can see the fossilized remains of trees more than six feet in diameter that lived there more than 200 million years ago. Sarah Herve, the acting chief of interpretation for the park, tells Host Bobby Bascomb about the unique geological process that preserved the ancient trees. (09:08)

Offsetting Your Carbon Footprint

View the page for this story

Carbon-intensive activities including global air travel have been growing for decades. For individuals and companies interested in reducing their carbon footprints, carbon offsets promise to mitigate the damage caused by flying and other emissions sources through the investment in projects that either sequester carbon, like reforestation or forest conservation, or develop alternative energy infrastructure that reduce future emissions. Cool Effect CEO Marisa de Belloy discusses her non-profit crowdfunding platform that sells these offsets with Host Bobby Bascomb. (08:28)

"Hadestown" Brings Climate Change To Broadway

View the page for this story

Tony Award-winning musical "Hadestown" retells the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice with a Great Depression-inspired industrial post-apocalyptic setting. The show infuses themes like isolationism, exploitation of workers, and even climate change with New Orleans jazz, folk, and pop music. Director Rachel Chavkin joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss the show’s environmental themes. (08:21)

Camels at the Henbury Craters

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The wild dromedary camels of Australia's Henbury Craters are not native to the area, but they thrive in the dry heat nevertheless. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, bears witness. (03:25)

BirdNote®: House Sparrows’ Dance

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Many wild animals go out of their way to avoid humans and our structures, but some seem to thrive in the built environment. Such is the case of the House Sparrow, a common sight and sound from home improvement stores to rural barns and churches. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has more on this chirpy little bird. (02:06)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Rachel Chavkin, Marisa De Belloy, Sarah Herve, Sandra Steingraber

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Hundreds of studies link fracking to cancer, birth defects, preterm birth, and other public health impacts.

STEINGRABER: We uncovered no regulatory framework that could avert these harms. So in other words, there's no evidence that fracking can operate without threatening public health directly, or without imperiling climate stability, on which public health of course depends.

BASCOMB: Also, the Tony award winning musical “Hadestown” a retelling of ancient Greek myth and a parable about climate change.

CHAVKIN: The metaphors of industry and there being this terrible imbalance between how an industry consumes the natural world and what the natural world is able to sustain and give on its own, are all through the piece.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Fracking and Your Health

Fracking pads and roads, seen here from the air, can turn a rural landscape into a network of industrial infrastructure. (Photo: Simon Fraser University, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

Fracking has revolutionized the extraction of oil and gas in just a few years. By forcing water, sand and chemicals into shale rock at high pressures, companies can extract more oil and gas than using conventional wells. But this highly efficient method comes with environmental and health risks, and a growing body of research ties the fracking activities to a host of health problems including birth defects, cancer, and asthma. A new meta study jointly published by Physicians for Social Responsibility and Concerned Health Professionals of New York brings together the findings of more than 1700 studies, articles and reports on the health impacts of fracking. It’s the sixth edition of a report originally released in 2014, which helped inform New York State’s decision to ban fracking. A group of public health professionals that included Sandra Steingraber, a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College, wanted to make sure science was part of that decision.

STEINGRABER: So we went to work, translating the science into plain English for our political leaders, members of the press, and most importantly, people in frontline communities who are going to be compelled to endure the risks that fracking brings to people's health. And when we first did this, we didn't call it a compendium, we called it a memo, [LAUGHS] because there were only nine studies in the peer-reviewed literature. And then when we finally banned fracking in New York in December 2014, we had an edition of the compendium with 400 studies. Well, at that point, people all over the world were at this same point in thinking about fracking, whether to allow it or not allow it. And so our Compendium was in great demand. So we've kept going with it.

BASCOMB: So what was your basic finding in this most recent report?

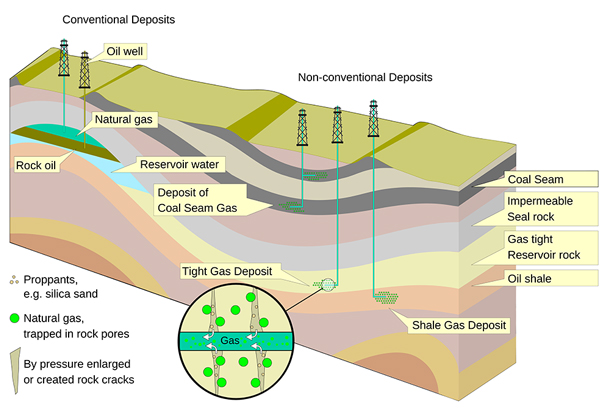

A diagram of “non-conventional” deposits accessed via fracking, which releases tightly-held oil and gas within shale rock. (Photo: MagentaGreen, Wikimedia Common CC BY-SA 4.0)

STEINGRABER: Well, we looked across a wide range of parameters. We looked at air pollution, water pollution, radioactivity, social disruption, we looked at impacts on climate. And across all these data, we saw a plethora of recurring problems and harms. And we uncovered no regulatory framework that could avert these harms. So in other words, there's no evidence that fracking can operate without threatening public health directly or without imperiling climate stability, on which public health of course depends.

BASCOMB: And so what are the public health concerns associated with fracking?

STEINGRABER: Well, there are 17 different topics in this Compendium and it starts off with air pollution. Air pollution accompanies fracking wherever it goes; things like methane leaks that result in smog, ground level ozone, which is a killer. So we know ground level ozone contributes to stroke risk, to premature birth, to heart attack, and to asthma. And then when we actually looked at public health effects measured directly, we saw in places where there is a lot of fracking activity, the kinds of health effects that are linked to this kind of air pollution. And I think what we would agree is the most troubling, is pregnant women who live near drilling and fracking operations during pregnancies are at higher risk for poor birth outcomes, including premature birth, including certain kinds of birth defects, including small for date births, meaning, infants are born quite small for the number of months of pregnancy.

BASCOMB: And is the only way that people are exposed to it is by air, or is it also in the water?

Studies show pregnant mothers living near fracking operations are at a higher risk of delivering their babies early. (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

STEINGRABER: Water contamination by fracking is a proven thing. Fracking relies on using our fresh drinking water sources as a club to shatter the shale below our feet. The idea here being that there are bubbles of methane -- natural gas -- and oil that are actually trapped inside the rock, they won't flow up the borehole on their own. So we use our freshwater resources to shatter the shale and get at those bubbles of methane. But when the water comes back up again, it's contaminated not only with toxic fracking chemicals that were added in the first place, but also there's a whole periodic chart of toxic chemicals down in the shale, things like heavy metals, arsenic, barium, strontium, uranium. And some of these things, like radium and radon, are actually radioactive. And the question is, how do you dispose of all that? And the actual standard practice is to re-inject it into the ground again. But this raises the risk for contaminating our drinking water aquifers, which this wastewater has to be pushed through. And in addition, because there are lots of lubricating chemicals that are added to fracking fluid, you can actually lubricate fault lines and trigger earthquakes. And we have a whole section dedicated to public health and safety risks around seismic activity.

BASCOMB: Now I understand that there's also an environmental justice component to fracking and health impacts. Can you tell me about that please?

STEINGRABER: Fracking has an environmental justice component for sure. The oil and gas, of course, are located under many parts of the United States. But where fracking infrastructure and fracking well pads are located, turn out to be disproportionately sited in communities of color, poor communities, and rural communities. No one wants to live next to a massive, loud industrial zone that 24/7 exposes you and your family to toxic chemicals, to noise pollution, with massive truck traffic going back and forth, risk of earthquakes and so forth. And so toxic facilities tend to be sited in communities that can offer the least resistance, in communities where people don't necessarily have friends in Congress, they don't have legal assistance, it's difficult mount a strong resistance. In one case in Colorado that we looked closely at, fracking well pads were initially planned to go in next to a school servicing largely white children from wealth, in a wealthier community. And that community succeeded in pushing it back. And then it landed next to a school where a lot of poor kids, who were not white, and whose parents didn't speak English, and perhaps had undocumented immigrants living there, who were less likely to speak out.

BASCOMB: And this report also looked at how fracking contributes to climate change. Can you tell me what you found along those lines?

STEINGRABER: Climate change is the big theme of the sixth edition of the Compendium. And that's because the data are really clear now that methane is surging in the atmosphere. It started rising really rapidly around 2007. And methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, about 86 times more powerful over a 20 year timeframe than carbon dioxide. And 20 years, of course, is about the length of time we have left to really get the climate stabilized and decarbonize. So we have to look closely at methane. So increasing evidence suggests that North American fracking operations are driving a lot of that surge. And we're discovering that fracking operations and all their attendant infrastructure, all the way to the pipelines, to the compressor stations, to the distribution pipes that bring it into your home, are far more leaky than we formerly appreciated. And there are no good fixes for this problem. So all of this is quite alarming, showing us that fracking is absolutely incompatible with climate stability.

Methane, which is most of what makes up natural gas, is a very potent greenhouse gas, and studies have shown that it can leak via infrastructure from the point of extraction, through pipelines, all the way to the point of use. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: But we've been told that fracking and natural gas is a bridge fuel, that it's going to help us get out of the problem with climate change.

STEINGRABER: [LAUGHS] Yeah, the metaphorical, mythical bridge. That's been an industry talking point since the very beginning. And there was never really a lot of data to suggest that natural gas worked that way, but at this late stage in the climate crisis we find ourselves in, we know that that's absolutely not the case. To put a more hopeful spin on it, and why the bridge metaphor doesn't really make sense, is that we're already on the other side of the water, right? We have renewable resources that are deployable now, in the form of solar, wind and water power that can be backed up with battery storage, obviating the need for fracking. So fracking is no longer a bridge. It might have been a bridge 80 or 90 years ago. Today, it's a wrecking ball that is swinging at our climate.

BASCOMB: So what kind of reception have you had to your report, now that it's out?

STEINGRABER: We get emails every week from people who are submitting it as expert commentary, bringing it to their elected representatives, holding reading groups in their synagogues and churches. It's always gratifying to see, especially in this day and age where this administration has turned its back on science in general and on climate science in specific, to see people hungry for this information. And from the ground up this science is really making a difference.

BASCOMB: Sandra Steingraber is a professor of Environmental Studies and Sciences at Ithaca College and coauthor of the sixth Fracking Science Compendium. Sandra, thank you so much for taking this time.

STEINGRABER: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Sixth Compendium of Scientific, Medical, and Media Findings Demonstrating Risks and Harms of Fracking

- Environmental Health News | ““No Evidence” That Fracking Can Be Done Without Threatening Human Health: Report”

- About Sandra Steingraber

[MUSIC: The Original Cast of “Once,” “Falling Slowly (Reprise),” by Glen Hansard & Marketa Irglova, Original Cast Recording of “Once,” Sony Music Entertainment/Masterworks and Masterworks Broadway]

Beyond the Headlines

Increasingly, Native American tribes across the United States are installing solar panels on tribal lands as a way of boosting their economies. (Photo: Solar Nation, GPA Photo Archive, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. You know, for years, Native American reservations in many cases have boosted their economies, even become prosperous through a couple of odd forms of reparations: gambling casinos, and the sale of untaxed cigarettes. And there's something that's beginning to pop up in a lot of reservations out West, that's maybe a more benign and traditionally comfortable form of revenue generation. And that's solar energy on Native American reservations.

BASCOMB: Great, and how widespread is this idea of selling solar instead of cigarettes?

DYKSTRA: Oh, there’s a foundation that's been set up by making small grants for small scale projects. There are also big projects, the most noteworthy of which is probably the Navajo Nation in Arizona; the Navajo Coal Generating Station was a major source of pollution and CO2 in the American Southwest. The Navajo station is closing down. It's no longer cost-competitive, in addition to its pollution and climate problems, and the Navajo government is looking more and more to solar to begin to fill the gap that's going to be caused when Navajo coal is no longer producing power.

BASCOMB: Well, that's very forward thinking. What else do you have for us this week?

Gerweiler is an open coal mine West of Germany. (Photo: Bert Kaufmann, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We're going to stick with coal for a minute and go to Germany. Over several decades, Germany's actually planned for the demise of its coal industry. We know that coal -- for climate reasons, for competitive reasons -- is on the decline throughout the world, particularly in the United States. Germany has known for long time, long before concern about climate change, that its involvement in the coal business was coming to an end, because they're running out of domestic coal to mine. There have been plans to convert miners and mining communities to not only cleaning up the old coal facilities, but finding new businesses, founding new universities in coal towns to help them make that switch.

BASCOMB: Wow. So are there some lessons to be learned here for American mining operations?

DYKSTRA: A not-so-good lesson because that same kind of preparation for conversion has never happened in the United States.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Let's do a little Living on Earth goes to the movies. There been some real stinkers of movies done about the environment over the years. I'm thinking specifically about one that was released on July 24, 1971. It involved legendary movie bad guy, Godzilla, who turned into a good guy and an environmentalist in one of the long series of Godzilla movies. This one was called “Godzilla Vs. The Smog Monster”.

BASCOMB: And what was a smog monster, and how was Godzilla supposed to help?

DYKSTRA: Well, instead of stomping Tokyo, which was Godzilla's reputation to date, Godzilla actually saved Tokyo from Hedorah, the smog monster who spit out sludge and spewed smoke all over Tokyo in a way that encouraged moviegoers to think that Tokyo's very real pollution problems were caused by prehistoric monsters and solved by prehistoric monsters, rather than being maybe a little bit more man-made.

Godzilla vs. Hedorah, also known as Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, is an apocalyptic movie featuring Godzilla saving the earth from a monster created by pollution. (Photo: Tom Simpsom, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Sounds like maybe a little bit of propaganda then.

DYKSTRA: A little bit of propaganda, but we don't want to let Hollywood off the hook for bad environmental movies.

BASCOMB: Oh, no, indeed. I think one of the worst movies of any kind I’ve ever seen was “Waterworld”. I saw it back in the day and I thought Geez, there's two hours of my life I'm never going to get back.

DYKSTRA: And those two hours were in July of 1995 when “Waterworld” was released, or foisted on an unsuspected public. It was a stinker of a movie. It depicted a dystopic future world where everyone lived at sea because of sea level rise. People lived and died without ever seeing dry land. And they were also plagued by seagoing pirates called smokers who were led by Dennis Hopper, who ran a very, very ancient rusty Exxon Valdez and terrorized the good guys on the open seas.

BASCOMB: All right, Peter. Well, thanks for that news. We'll talk to you again next week.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Bobby, talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And there's more on these stories on our website, loe.org.

[Godzilla Vs. The Smog Monster – Trailer]

KID: Godzilla!!

MAN: Godzilla vs the Smog Monster. Nothing men can do can stop the Smog Monster.

[SCREAMS]

MAN: Can Godzilla save the earth from this mastodon of destruction?

Related links:

- Bloomberg Environment | “From Gambling to Solar, U.S. Tribes Bet on New Revenue Stream”

- The Sydney Morning Herald | “How Germany Closed its Coal Industry Without Sacking a Single Miner”

- Read more about Godzilla vs. Hedorah

[MUSIC: SAVE THE EARTH (English version of "Kaese! Taiyou Wo") Lyricist: Guy Hemric, Adryan Russ, Composer: Manabe Riichiro, Singer: Adryan Russ, 1970 AIP Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up, a trip through ancient time in one of our national parks.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Issi Rosen, “Mediterranean Samba” on Homeland Blues, by Issi Rosen, Brownstone Records]

Exploring the Parks: Petrified Forest National Park

Petrified Forest National Park reaches into the Painted Desert in Arizona, which boasts a colorful badlands ecosystem. (Photo: Woody Hibbard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]

BASCOMB: We continue our series on US public lands now with a trip to one of our more unusual National Parks. Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park is full of wildlife, and the beautiful hiking trails that we’ve come to expect in our public lands. But what really sets it apart are the trees that died there more than 200 million years ago. The fossilized remains of those trees, logs more than 6 feet in diameter, are still there today, cast in stone. Here to explain more about the unique geological process that preserved the ancient trees is Sarah Herve, the acting chief of interpretation for the park.

Sarah, welcome to Living on Earth!

HERVE: Thank you. It's great to be with you.

BASCOMB: So what exactly is petrified wood? How was it formed?

HERVE: So petrified wood is a fossil. A lot of times people think that it's something different than you know, any other kind of fossil, which is basically the fossilized remains of some living organism. And in our case, the petrified wood is the remains of gigantic forests that were here during the Late Triassic. The logs that we now find, you know, on their sides on the ground, have been turned to stone by rapid burial. There's silica in the materials that the trees were buried in and the cellular structure has been replaced by silica. There's other minerals present, but the glassy mineral silica is really, really good at exchanging places with cellular material. And that's why you have maybe, you know, a big piece of petrified wood that still looks like wood, but then you go to pick it up, and it's really heavy because it's been turn to stone.

BASCOMB: So the end result then, is you have these logs lying around that look exactly like trees, you can see the rings in them, the bark, the whole thing, but it's stone.

HERVE: Yeah, exactly, yeah. And in some cases, we can't see any of the rings, the petrification process has been so complete, that all of the cellular structure of the rings, everything has just blown apart. But that wood is oftentimes what we call rainbow wood, because it's very, very colorful. And so on the outside, it may look just like, you know, regular wood, or kind of a reddish color wood. But then when you look on the inside, there's all kinds of pinks and purples and blue colors, blacks, and it's really just amazing. The amounts of petrified wood are also very staggering, and the size of the logs in some cases, you know. If you can picture these logs when they were trees, they would be comparable to like the giant sequoias of California.

BASCOMB: And these trees were living some 225 million years ago. What are scientists able to learn about the geology of the area and the trees themselves from studying this petrified wood?

HERVE: So by looking at the rocks and understanding the rocks and the geologic setting, paleontologists and geologists are able to understand that this part of northern Arizona was a much more tropical kind of environment. We were closer to the equator at that time, the continents were together to form Pangaea, there was quite a bit more water through this region. And that's, I mean that's based on looking at the different fossils that are found within these rocks and the rocks themselves. It's thought that there was a tremendous river system that was running through this area. And when I say large river, I'm talking about something on the same magnitude as like the Mississippi or the Amazon River. So a huge, you know, very, very wide river that goes for hundreds and hundreds of miles.

Petrified Forest National Park’s name comes from its famous fossils of fallen trees from the Late Triassic, about 225 million years ago. (Photo: Kumar Appaiah, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: And this is Arizona we're talking about, so things have changed a lot.

HERVE: [LAUGHS] Right, exactly! Yeah. So our current environment, when you look at it, it's really hard to imagine, you know, a place so full of trees and crocodile-like animals running around and lots of amphibians, right. Those are some of the different fossils that we find. And you know, when you look around today, we are in the middle of a big beautiful grassland. And then we have, you know, incredible badland topography. So that's what a lot of people, you know, call the Painted Desert. And it is very, very colorful, that's why it gets that name. But those deposits are the remains of those ancient rivers.

BASCOMB: And you alluded to this just now, but trees aren't the only things that you have preserved in the park, I understand you have a large trove of dinosaur fossils there.

HERVE: The dinosaurs that we find at Petrified Forest, they're generally pretty small. So we're at a time way before all the big dinosaurs happened. So you know, the Triassic was a time when a lot of animals were, you know, their lineages were getting started. And those lineages became many of the animals that we're familiar with today, especially in the reptile and amphibian world.

BASCOMB: I understand that you also have petroglyphs there, left over from early inhabitants of the area. Can you tell me about those?

HERVE: Yeah, so, we have a 13,000-year archaeological record here in the park, so that's continual occupation of some indigenous people. And we can see through the archaeological evidence that we find in the park, people coming and going in the area and technologies changing. The petroglyphs themselves are really interesting. There's a lot of petroglyphs or what we call rock art in the park. There's different, you know, sometimes animistic forms. So you'll see things that look like different kinds of birds or things that look really obviously like deer, you know, or elk or pronghorn antelope, which are animals that still live in the park today. And then some of the forms are very, very strange, and really hard to interpret. Some of the petroglyphs are also considered what we call solstice markers, or solar calendars. And so they have light interactions with the sun during different times of the year, usually associated with either the solstice or the equinox.

BASCOMB: So with all of these ancient records, the park must just be a treasure trove for archaeologists and paleontologists. What kind of research is going on there today?

Petrified Forest National Park was made a national park in 1962, when it had previously been a national monument since 1906. (Photo: Barbara Ann Spengler, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

HERVE: It definitely is! [LAUGHS] You know, we have a variety of different kinds of researchers, you know, so even within the world of paleontology, you might have someone who's specifically focused on aetosaurs, which is a type of crocodile ancestor. Or you might have someone who studies fossil pollen. Paleobotanists, you know, so people that are coming and studying the plant material, not just the logs, but we find incredible, like fossil ferns and cycads and other, you know, kinds of plants that you usually associate with more tropical environments, than the grasslands of northern Arizona. And then the archaeology story is equally as exciting and have lots of interest from archaeologists in this place, simply because we have an incredible amount of archaeological material and we have that long time span of continuous occupation. And then also because of where we're located, and that there are still descendants of the people who called this place home, you know, for thousands of years.

BASCOMB: And I understand there's also some pretty spectacular hikes in the park. Can you tell me about some of the most popular trails there and the unusual landscape that visitors walk through on them?

HERVE: Sure, we do have a variety of hiking trails that are, you know, some are paved, some are just, you know, sort of a dirt surface. Most of those are fairly short walks, they can be either, you know, into some of the badland formations, for example, the Blue Mesa, which is a favorite area of mine, and a lot of visitors enjoy going there. It takes you into a canyon, where you're walking amongst layers of purple and green and red. And then you know, we have a walk that goes around an ancestral Puebloan village called Puerco Pueblo, and you can see petroglyphs from the trail there. You know, we also tell stories associated with Route 66 because we have a section of Route 66 preserved within the park. So you know, you can do a variety of different trails and see a variety of different things in the park that encompass all of our different themes.

BASCOMB: And, you know, we have a lot of national parks in our country; we're very lucky that way. Why should somebody visit this park as opposed to any other?

Archaeological sites, such as petroglyphs carved into rock surfaces, suggest that people lived in the park as long as 8,000 years ago. (Photo: Finetooth, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

HERVE: You know, what I hear from a lot of park visitors is, you know, “wow, we're so glad we came here, we like this better than Grand Canyon!” And that's not a dig on Grand Canyon. But it's always interesting to me to hear that because I think a lot of times people don't realize right when they get off the interstate what they're in for, and then they get in the park and they're driving through and they see the different scenes of the Painted Desert and go into the museum and learn more about the park, and they just realize that this place has so much to it, that you know it can be kind of underestimated at first glance.

BASCOMB: Sarah Herve is the Acting Chief of interpretation for Petrified Forest National Park. Sarah, thank you for sharing the park with us today.

HERVE: Thanks so much for having me on the show. And I hope to see some of your listeners visit us in the Petrified Forest National Park.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Petrified Forest National Park

- Listen to a recent Living on Earth segment on the US National Parks

[MUSIC: Chuck Berry “Route 66” on New Juke Box Hits, Written by Bobby Toup, CHESS Records]

Offsetting Your Carbon Footprint

Many carbon offset projects seek to preserve carbon through the protection of forests. (Photo: Loren Kerns, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well if you are planning to visit some of our national parks this summer you might also be thinking about the carbon you’ll emit to get there. Carbon offsets are one way to reduce or eliminate our carbon footprint, and dozens of businesses offer ways to do it. For more on how carbon offsets actually work, we turn now to Marisa De Belloy, CEO of Cool Effect, a non-profit crowdfunding platform that sells carbon offsets. Marisa, welcome to Living on Earth.

DE BELLOY: Thanks, great to be here.

BASCOMB: So what do people choose to offset with your carbon emissions offset program?

DE BELLOY: So people come to Cool Effect to offset a whole bunch of different things. So, they'll offset a flight, they'll offset their trips to work; some will offset their entire year. The average American emits about 17 tons of carbon pollution every year. And so some people like to wipe that clean by offsetting that at Cool Effect. These are people who are committed environmentalists who are already doing what they can do in their daily lives, to reduce their impact. And that might be eating less meat, it might be traveling less often, it might be having an electric car or solar panels. And they're looking to either, you know, erase their impact entirely and go neutral, or to really just do more to fight climate change.

BASCOMB: So give me some examples of projects that participate.

DE BELLOY: We have a wide variety of projects. We have a team of scientists who go out and figure out, you know, which projects are really doing what they say they’re doing. We do what we call “triple-verifying” their projects. So each of these projects will have met the requirements of an independent standard, they'll have been verified independently of us, and then we do our own very deep due diligence that lasts a couple of months on each project, to make sure that they're doing exactly what they say they're doing. And that leads us to projects all over the world. So we have a project, for example, in Vietnam that installs biogas digesters, which is a very simple technology that takes animal waste, and turns it into clean cooking fuel for homes. We have a project in the United States that's protecting the forest, or another one protecting grasslands; a project in Honduras that is providing clean cookstoves for families down there who were basically dying from air pollution from cooking over open fires, who now have a clean source of cooking that's also obviously good for the planet. But it's also about, you know, families and health. And each one of these projects, and they're really, we have a range all over the globe and at different price points. But they all are truly additional, meaning they're truly having an impact on the planet. And then they also all have their own set of co-benefits. So you know, for the cookstove project, it's the health of the families. In some cases, it's local jobs. In some cases, it's protecting wildlife or a whole forest ecosystem and the people who live there. So we try to have a real range. But the key thing that underlies all the projects is that we have made sure that they're actually doing the work of verifiably reducing carbon emissions.

BASCOMB: And how do you actually verify that? I mean, how do you know that this project wouldn't have been done anyway without this money?

Some consumers purchase carbon offsets when partaking in carbon intensive activities like air travel. Various airlines such as JetBlue, Delta, and Alaska Air have offered optional carbon offsets when booking flights. (Photo: Sean MacEntee, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

DE BELLOY: Well, I mean, there's a couple of different ways, but one is you have to understand what their financial model is, both when they started the business and currently. Is there a profitable way to do what they're doing without the revenue from carbon offsets? And if the answer is yes, then the project is likely not additional. Another way to look for additionality is regulatory additionality. So, is there a law in place that's requiring this business or this nonprofit to do what it's doing? And you know, that might seem obvious, but in many cases, it's actually not that obvious. Because if there's a law in place, then people are going to do it anyway. There's another one in the developing world: is this standard practice? So for example, there are some areas in the developing world where more efficient cookstoves are standard practice. And you know, and that's a great thing. But you wouldn't go and start a cookstove project there and call it additional, because it's something that people generally speaking already have access to.

BASCOMB: And then once you've identified a good project to work with, how do you guarantee the longevity of that? I mean, I saw that you have one in Brazil, protecting the Amazon, and Brazil is a famously lawless area, especially with the new president that really doesn't encourage conservation. How can you be sure that those trees will still be standing 10 years from now, or that the landowner won't take that money and then clear cut in a different area?

DE BELLOY: So on the trees still standing portion, that's built into the methodology, so they will no longer be able to offer credits if those trees start disappearing. And each of the methodologies includes a certain buffer amount of trees, you know, because trees do die, and you can have natural fires and that sort of thing. And we take a particularly conservative approach to these projects, if there's any doubt that, you know, the cook stove was in use, or the tree was still standing, or, you know, the animals were still having access to these grasslands, then a credit is not issued for that amount. So wherever there's doubt, the credit is not issued. The only credits that are issued are for places where you're absolutely certain that carbon has been sequestered or removed. Now on the point about, in forestry, it's called leakage. And that's the idea that you do save a piece of forest in one area. And another piece, you know, somebody just shifts and cuts down a different forest. That's a really tricky issue. And again, it requires a lot of monitoring. We do a lot of work to ensure that's not the case. It's very, very hard to say, 100%, for sure that, you know, that it hasn't happened, and particularly when you go beyond national borders. So it's one thing to look in Brazil, and there's actually some great drone technology now to map out forestry all across the region. And so you can see, you know, very easily and quickly what's been cut down and what hasn't. But, you know, I'm the first to admit that there's no way to really do it 100%, for sure and particularly when you go across national borders. So did that Brazilian entrepreneur who wanted to cut down the forest, switch over to the Ecuadorian side? It's very hard to know. We're out there trying, but it's hard to guarantee for certain.

BASCOMB: And do you send people to actually audit these projects and hold them accountable?

DE BELLOY: Yes, yeah, we do. So as part of their credit issuance process, which again, goes through one of the major international standards, like The Gold Standard, or the Climate Action Reserve here in California, they will already have an independent verification and have to meet a certain set of standards and provide a whole bunch of information. But then we on top of that also will verify the projects.

BASCOMB: And how much does this cost for consumers? How much is a ton of carbon dioxide? I understand there's different prices based on which project you're supporting. But how do you come up with those costs, and what are they to begin with?

Many of the carbon offsets offered by Cool Effect are less than $10 for a metric ton. (Photo: Frank Douwes, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

DE BELLOY: Well, the costs are actually very reasonable. So it goes from about $5 to about $13 a ton. So if you think about the average American having 17 tons of carbon pollution every year, it's a really reasonable amount of money to spend to wipe away that impact that we're all having. And the way Cool Effect does it in terms of pricing is we try to, you know, unlike other providers, we work directly with the project to understand what their financial model is; to understand, actually the inner workings of the project, and to really come up with what is a reasonable price, both for the project and for the customer.

BASCOMB: The problem of climate change can seem so overwhelming and so daunting. How big of an impact do you think this approach can have to really addressing it?

DE BELLOY: I mean look, we all need to do everything we can in every possible way to fight climate change, because this is such a big problem. So if you look at carbon credits, outside of the mandatory schemes, and there are, as you know, in California, there's a cap and trade system, which involves carbon credits, and there's one in Ontario, and there's a few others that are coming into place. But just on the voluntary, so people like you and me who are buying carbon credits. Already about 400 million tons of carbon pollution has been removed, just in that way. So I mean, that gets to a fair number, and the market is actually growing. More and more businesses are thinking about doing this, the airlines have gotten together and are thinking about implementing a big carbon offset scheme. So you can actually have a pretty decent impact. And I'd say that for individuals, what's really important is to do the next thing that you can, to start having some impact. Because if we're all doing something, that adds up to a very large impact, and that's why we named our platform Cool Effect. The Cool Effect is like the butterfly effect. It's the idea that if enough people do take small actions, then we can have a big impact together.

BASCOMB: Marisa de Belloy is CEO of Cool Effect. Thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

DE BELLOY: Thank you. It was a lot of fun.

Related links:

- CoolEffect.org

- NYTimes | "If Seeing the World Helps Ruin It, Should We Stay Home?"

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Mountain Laurel” on Woodland Dance, by Joshua Messick, self-published]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Camels native to the Sahara find a home down under. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Mountain Laurel” on Woodland Dance, by Joshua Messick, self-published]

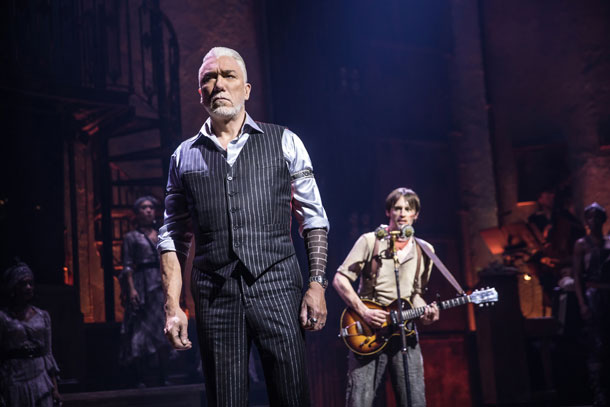

"Hadestown" Brings Climate Change To Broadway

Hadestown garnered 14 Tony Nominations and won eight Tony Awards including Best Musical. Pictured, Amber Gray plays Persephone. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

According to ancient Greek myth, Hades, ruler of the underworld, kidnaps the Goddess Persephone and brings about the first winter on earth. For writer Anaïs Mitchell, that sudden change in the climate is the perfect backdrop for the story of her Tony Award-winning Broadway musical “Hadestown”. The show infuses the theme of climate change with New Orleans jazz, folk, and pop music. Here to tell us more is the director of “Hadestown”, Rachel Chavkin. Rachel, welcome to Living on Earth.

CHAVKIN: Thanks very much.

BASCOMB: So for someone that hasn't seen the show or listened to the music yet, can you give me a quick summary of what it's about?

The musical tells the Greek Mythological tale of Orpheus and Eurydice in a Great Depression-era-inspired, post-apocalyptic setting. Reeve Carney and Eva Noblezada play the characters on stage. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

CHAVKIN: Yeah. So “Hadestown” is a retelling of an ancient story, for those who know their Greek mythology, which is the Orpheus and Eurydice story, as it intersects with the myth of Hades and Persephone. Eurydice says -- I think these lyrics are no longer exactly in it, but -- "flood will get you if the fire don’t”. So there's a sense that the above world is a dangerous place. But you hear about this mythic place, which is Hadestown, and Hadestown is a land of plenty and a land where you sort of aren't ever worried about where your next meal is going to come from. And so during Act One Eurydice chooses to go down to Hadestown, and the audience along with Eurydice discover that Hadestown is actually basically this proto-fascist state. And you hear about a wall that is getting built, and the wall will never be done. And Orpheus comes down to Hadestown to try to get the love of his life back.

BASCOMB: So here at Living on Earth, we tend to look at everything through the lens of the environment. But it seems pretty clear to me that there's some clear allusions to climate change. Can you tell me about that?

CHAVKIN: Yeah. So the image of the climate being out of whack has been a core one for Anaïs since she started writing the show. And so as we thought more and more about shaping the world that Eurydice and Orpheus are living in, a world caused by, in Greek mythological terms, the decay of this ancient marriage between Hades and Persephone, a world that is out of balance, where it is either freezing or it’s blazing hot, and that food becomes a really, you know, a scarcer substance and the idea of stability becomes harder to imagine, and that Eurydice is, is a character who has spent her life running. All of those are things that kind of crystallized while we were making the show.

BASCOMB: Well, let's play a song from the show. I want to play a clip of “Any Way the Wind Blows”. But before we do, can you set it up for me? What's happening at this point in the storyline?

CHAVKIN: Yeah, so “Any Way the Wind Blows” is really right at the top of the story. It's really where you hear her, this kind of tough chick who is this survivor, walk into this bar, that is Hermes' bar where she will eventually, right after this song, meet Orpheus, the love of her life. And she talks about how screwed up the weather is.

Hadestown is an underground factory that serves as refuge from the weather above. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Any Way the Wind Blows”, By Anaïs Mitchell]

Weather ain't the way it was before.

Ain't no spring or fall at all anymore.

It's either blazing hot, or freezing cold. Any way the wind blows.

And there ain't a thing that

you can do when the weather takes a turn on

you, 'Cept for hurry up and

hit the road. Any way the wind blows…

BASCOMB: So that song seems a little post-apocalyptic, but in keeping with what scientists tell us to expect with climate change, you know, shifting seasons, droughts and floods. Was that the idea here?

CHAVKIN: Definitely Anaïs was profoundly impacted by the news that was happening. I mean, every day while we were making this, while we were making this work. During the last fire season when California seemed to be you know, totally, totally a flame. And, and then meanwhile, on the East, you had these tremendous floods that now we're seeing in the Midwest. Yeah, all of that, all of that news impacted the lyrics and imagery of the, of the show.

André De Shields plays Hermes, the show’s narrator. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Any Way the Wind Blows”, By Anaïs Mitchell]

When your body aches, to lay it down.

When you're hungry and there ain't enough to go round.

Ain't no length to which a girl won’t go

any way the wind blows.

BASCOMB: You could probably make the argument that Eurydice is considered an environmental refugee. I mean, she leaves her cold home in seeking something that's safe and warm in Hadestown. To what degree do you think that that's true?

CHAVKIN: I would say that is very fair to how we discussed it. You know, I think that there is the idea that Eurydice, has many, many things, many demons chasing her; the weather is one of them. The weather is of course, also a metaphor for economic injustice. She makes the choice to go to Hadestown, you know, she's choosing between the love of her life and the ability to have food, and know that she has a place to sleep and a bed to lie down in, and a job to go to, so that the environment is part of what she's running from is exactly right.

BASCOMB: Now, Hadestown is actually an underground factory, and maybe indirectly, the source of the problems above ground, you know, the changes in weather and so; that also seems pretty clear commentary on the toll that industry is taking on our environment.

Patrick Page plays Hades, an industrial CEO of the Hadestown factory. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

CHAVKIN: Definitely, the metaphors of industry and there being this terrible imbalance between how an industry consumes the natural world, and what the natural world is able to sustain and give on its own, are all through the piece. Ultimately, we think about the marriage of Hades and Persephone, and this marriage between industry and nature, as being one that it's not to say, industry is bad, it's to say that industry is totally out of balance. And as we understand it, that Hades was always a builder, but that at a certain point, when he began to be afraid that Persephone wouldn't come back to him. And he began to be jealous of her time away -- you know, the mythological six months that she had above ground -- that he began to over produce and consume. And there's this image of his jealousy, sort of almost spreading like an oil slick across the land. And Hadestown is the product of that. So it's almost like industry on steroids.

BASCOMB: Well, at the end of the day, what do you hope that people will take away from watching “Hadestown”, from experiencing the music and the show?

CHAVKIN: Hadestown is about many things. But for me the final image and the image that I hope that people leave with happens during “Road to Hell II”. It's the final song in the show proper that Hermes sings. And there's this image of, yes, it's a sad song. It's an old song. But we sing this song, we sing the story of Orpheus and Eurydice anyway, because there is hope in the simple act of retelling the tale. There is hope in the community that gets gathered to hear the tale and that essentially with each generation, the needle moves a little bit, whether we see change in our lifetime or not.

Eva Noblezada as Eurydice. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

BASCOMB: Rachel Chavkin is the Tony Award-winning director of “Hadestown”. Rachel, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

CHAVKIN: It's a pleasure.

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Road to Hell (Reprise)” By Anaïs Mitchell]

See, Orpheus was a poor boy.

(Anybody got a match?)

But he had a gift to give.

(Give me that.)

He could make you see how the world could be

In spite of the way that it is.

Can you see it?

Can you hear it?

Can you feel it?...

Related links:

- Learn more about the show

- See Hadestown’s collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council

Camels at the Henbury Craters

Hundreds of thousands of camels roam Australia’s outback, including the protected Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve in Northern Australia. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: From Hadestown to another land down under…. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, found a creature that will make itself at home in nearly any hot, dry inhospitable place. "

Camels at the Henbury Craters

© 2017 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

Looking up, lying on my back, the Firmament is a bottomless well where infinite height turns to infinite depth and the worst kind of vertigo. The kind that derives from, our insignificance.

But the Milky Way casts like a net across the sky and there is comfort in that. Most days the wetted air of Long Island Sound makes it impossible to see. And the constellations are also preternaturally bright: Orion’s Belt rising as if from the ocean; Ursa Major named for a Bear and shaped like a cup; the Pleiades, those seven sisters candling the night light years from here; and the Great Magellanic Cloud.

Australia’s wild camels can have a negative impact on their environment, ingesting more than 80% of the available plant species and often fouling waterholes. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Meteor!

Angled low it splinters like a struck match exploding into parts. It leaves behind a pale green afterglow…. And now instead of being present as I was, I am thinking about… the red desert heart of Australia, and the middle, of the middle, of nowhere.

On a day that turned into an evening just like this, I strolled across the landscape of Henbury where a piece of the sky fell down, forty-four hundred years before. The dryness makes the desert night turn cold and I was shivering. From that, and from the thought of what it must have been like when some nameless thing broke free crashing through the upper atmosphere, and seven huge fragments arrived in a storm of fire. The craters left behind, no less apparent than the craters of the moon are Memory, brought into the present, from the distance and the past.

Though considered pests, these wild camels can be manageable if kept out of critical habitat, and at a moderate population. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Down to earth, I turned to go and there on the other side of the gravel road, also as if dropped from the sky, a herd of camels appeared. Eleven of them. Watching as if I was the alien one despite the seventy or eighty thousand years by which humanity preceded their presence. Here, for once, it is the camels, not human beings, who are newcomers. They don’t belong, yet have succeeded, some would say too well. This despite that they were brought without their consent, and when no longer profitable, thrown out, like rags.

Without water. In that heat. And no food. On foot, unwillingly into the silent desolation of Henbury I wouldn’t last a week, wouldn't last the day.

Maybe, this is what who belongs and who does not really means.

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- Learn more about the wild camels in Western Australia

[MUSIC: Sidney Gish, “Persephone” on No Dogs Allowed, Self-Recorded]

BASCOMB: You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org. That's LOE dot O-R-G. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you: You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Once again, comments@loe.org. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line, at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121.

BirdNote®: House Sparrows’ Dance

A House Sparrow shows off its courtship display (Photo: © Tony Marfell)

[BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BASCOMB: Many wild animals go out of their way to avoid humans and our

structures, but some seem to thrive in the built environment. Such is the case of the House Sparrow, a common sight and sound from home improvement stores to rural barns and churches. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has more on this chirpy little bird.

BirdNote®

House Sparrows’ Dance

STEIN: Back in 1559, Duke August of Saxony ordered that the House Sparrows of Dresden be excommunicated.

[House Sparrow songs and calls, ML 169771]

The familiar birds were slipping into Holy Cross Church and interrupting the sermon with their exuberant chirping — and, as Duke August described it, their “endless unchaste behavior” before the altar.

[House Sparrow songs and calls, ML 169771]

It’s nearly 500 years later, and they’re still at it. That manic chirping can now be heard almost worldwide. Their cheeping and peeping rings from suburban rooftops, home improvement centers, and yes, even the inside of some churches.

[House Sparrow songs and calls, ML 169771]

House Sparrows are at their noisiest, and their most endearing, during the male’s courtship display. As he struts and spins in front of his intended, the little brown Romeo puffs out his handsome black breast and droops his wings and cocks his tail to expose the silvery feathers of his rump.

[House Sparrow songs and calls, ML 169771]

Other males soon join in, their chirping growing ever louder and faster as they face off. All the fuss and attention act as a “super-stimulus” to the flattered female.

[House Sparrow songs and calls, ML 169771]

Look for the sparrows’ underappreciated dance in your neighborhood. It might just be enough to distract you from the sermon, too.

I’m Michael Stein.

###

House Sparrows seem to thrive in the built environment, and can often be heard chirping away in home improvement stores, barns and churches. (Photo: © Dennis Sanderson))

Written by Rick Wright

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 169771 recorded by Curtis A. Marantz.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org July/August 2017/2019 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# HOSP-04-2017-07-11 HOSP-04

References:

Bugs and Beasts Before the Law, by E.P. Evans http://bit.ly/2rGRHi0

Communal Display of the House Sparrow, by D. Summers-Smith http://bit.ly/2rTLmAX

https://www.birdnote.org/show/house-sparrows-dance

BASCOMB: For pictures of the House Sparrow, strut on over to our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the House Sparrow on the BirdNote® website

- Audubon information on the House Sparrow

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: House Sparrow Life History

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, by G.Velez, CMP Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Diego Arenas, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth