August 2, 2019

Air Date: August 2, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

View the page for this story

Deep within the remote wilderness of the Alaska Peninsula, Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve is one of the least-traveled places within the national park system. Designated by President Jimmy Carter as a national monument and preserve in 1978, Aniakchak is always open to visitors with no amenities, no cell service, and no park rangers -- hence its slogan, “No lines, no waiting!” Chris Solomon, who wrote about Aniakchak for Outside magazine, joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about his experience among the grizzly bears and volcanism in this wild and remote patch of public land. (12:02)

BirdNote: Exquisite Thrush Song

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Thrushes are widely regarded to have some of the most musical bird songs. BirdNote’s Michael Stein explains how these birds use a special anatomical structure to create their elaborate songs. (03:22)

Vegan Generation Gap

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

Traditional family recipes can go back through the generations, and that can present challenges when members of the newest generation go vegan. Ratatouille can be one answer, as Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran tells us. (03:01)

An Afternoon with Pete Seeger

View the page for this story

Renowned for his combination of music and social activism, the late folk music legend Pete Seeger explained to Host Steve Curwood on afternoon in 1998 that it was Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring that had inspired his environmental activism. They discussed how the year before the first Earth Day Mr. Seeger built a sloop he christened the Clearwater with the help of other musicians and activists, because that was his intention: to clear the waters of the Hudson River of pollution and garbage. In this interview that is a mix of story and song, he sounded notes of hope and harmony for this troubled world. (28:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pete Seeger, Chris Solomon

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Today a trip to one of the most stunning and least-visited places in our national park system.

SOLOMON: You can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And, it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it.

CURWOOD: And In this year when the late famed activist and folk singer Pete Seeger would have been 100 years old we recall how he got involved with the environment.

SEEGER: It was Rachel Carson's famous book "Silent Spring." I read it in The New Yorker, in installments. Up to then, I'd thought the main job to do is help the meek inherit the Earth. And I still, that's a job that's got to be done. But I realized if we didn't do something soon, what the meek would inherit would be a pretty poisonous place to live.

CURWOOD: That’s this week on Living on Earth.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Exploring the Parks: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Aniakchak’s renowned caldera is a beautiful reminder of Alaska’s location within the Ring of Fire. (Photo: Courtesy Chris Solomon)

Summer is a time of travel in the Northern hemisphere, and you have probably already had plans. But if you don’t or are thinking ahead to next year, we’ll be bringing you some stories in the weeks ahead that explore the vacation possibilities in US public lands.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co.]

CURWOOD: Today we look more than 5000 miles north to Alaska, and the Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. This spot on the Alaska peninsula it is one of the least visited of our public lands and touts the catchphrase, “No lines, no waiting”. And it’s for the most adventurous among us as there are no roads to access the preserve. You must arrive by plane or by foot and don’t think about going in winter. But Outside Magazine contributing writer, Chris Solomon, says that’s all part of the charm. Chris, welcome to Living on Earth!

SOLOMON: Oh, thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: What made you decide to go to one of the least visited places in the national park system?

SOLOMON: I really like to go as far off the map as possible. I mean, I've joked that my cell phone is a, is a bit like a reverse Geiger counter. As the cell phone bars of coverage drop, the possibility of adventure and a good time seems to increase. Everybody talks about the most popular national parks, and those places are great. But I wondered, what's the least popular place? And I wondered, is there something interesting about that place? Or maybe, why is it so unpopular? There was a list on the National Park Service website of the places that got the fewest visitors. And year after year, Aniakchak anchors the bottom of the list or is very close to the bottom.

CURWOOD: So, remind me, where in Alaska is Aniakchak actually located?

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve resides on Alaska’s peninsula, which leads into the Aleutian Islands. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: It's 350 to 450 miles, I forget exactly, southwest of Anchorage on this stub of a peninsula called the Alaska Peninsula that's warted with these quiescent volcanoes. It's where Katmai National Park is that people have probably heard of. Lake Clark National Park is in the area, these better known national parks. And then after the peninsula runs out, the Aleutian chain begins with people are probably more familiar with at least from a map. But, Aniakchak is on that peninsula as well. But, it's so little known that even as we sat in the airport, there was a big mural on the wall and these other national parks were on there and Aniakchak wasn't even on the mural in the airport as we headed there.

CURWOOD: What kind of company did you have with you, both two-legged and four-legged?

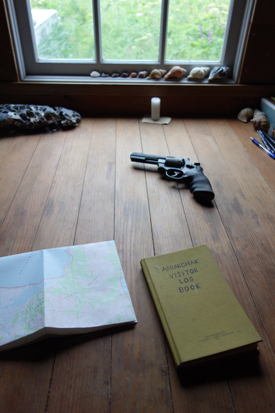

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so it was just three of us. There was a great photographer named Gabe Rogel, who's now a good friend. And our guide was Dan Oberlats who is the founder and chief guide of Alaska Alpine Adventures. So, it was just us three, along with a 44 Magnum called Pepe that was Dan's, to try and keep the bears at bay, because the Alaska Peninsula is, is known for some of the heaviest concentrations of the largest brown bears on Earth. They're relatives of the Kodiak brown bears, which are often said to be the largest bears, but the Alaska Peninsula bears are basically the same bears. One census found 400 brown bears per 600 miles, which is just astounding. I mean, there's something like 700 bears in 60,000 square miles of the Yellowstone ecosystem.

Chris’s guide carried a gun named Pepe to defend against grizzly bears. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Oh, my! So there you are, you head to Alaska, to Aniakchak, but I guess you just don't rent a car in Anchorage or something and start driving.

SOLOMON: No, you don't. So, you have to fly to for instance, King Salmon, which is one of the bases of the Bristol Bay Salmon Fleet, and then maybe try to get to Port Heiden, which is a little dot of a town. And then, from there, you could either potentially fly a float plane into the monument, or in our case, the weather's so bad and unpredictable that we just decided to hoof it from Port Heiden. And we hiked about 22 miles up into the centerpiece of Aniakchak, which is this spectacular caldera.

CURWOOD: What exactly is the caldera?

SOLOMON: Yeah, so a caldera is essentially a volcano that has blown up, and then collapsed on itself and leaves a big bathtub. Essentially an empty ring, maybe the one readers would know best is Crater Lake in Oregon. And so Aniakchak has this great history and, it was so fun to discover this stuff, Steve. About 7000 years ago, as the Egyptians were kind of doing their thing and really dominating the Mediterranean area, this several thousand foot volcano, Aniakchak would have been, blew its top with the force of something like 10,000 atomic bombs. And then it, having done that, it collapsed upon itself. And over the course of a couple thousand years, it filled with several thousand feet of water. So it was this bathtub, and then one of the sides burst out with this tremendous flood. So then it became this empty ring with a hole in one side. And one of the great discoveries of doing this story is, you know, the native peoples, of course, knew about this place. But then in the early 20th century, this incredibly charismatic guy named Father Joseph Hubbard, who was called the “glacier priest”, came and quote-unquote, rediscovered it. And the glacier priest was this swashbuckling Jesuit from Santa Clara University, he would go on these expeditions around, around Alaska, often with a bunch of football players from Santa Clara University with their leather helmets on and they went to Aniakchak and they explored it. And they had found this place that hadn't blown up again in a couple thousand years. And inside were all these orchids growing in the warm soil, and they had bunnies that hadn't seen man. And so they would just walk right up to the football players who, who then ate them for dinner. And he described this sort of paradise found. And he wrote about this for, you know, places like National Geographic, and then he went away, and that year, it blew up again, and he came back and he described this kind of Dantean Inferno, and the place almost killed them with all the sulphurous gases. And so he wrote about it again, and became even more famous. So the glacier priest was one of the great finds of this story, and I was able to kind of follow some of his tales and writings as we explored the place.

At the bottom of Aniakchak’s caldera is Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

CURWOOD: So take me back to a memorable moment or two for you in Aniakchak National Monument.

SOLOMON: We drop into the caldera after just being completely in the mist, you know, not knowing what we're going to find. And we drop into the caldera the second day, and we see this amazing place, and we camp by this beautiful little lake that's still the remnant of the bathtub that had been filled. And it's this lake called Surprise Lake where salmon still swim up into it and spawn, and they apparently taste like minerals from all the volcanic stuff that's still in the lake. And the next day we crawl out and we get on to the rim and you can look down and there are these pumpkin-colored hot springs that still push up out of the floor of the volcano. And it's just some of the most dramatic colors I've ever seen. And so you have this, you have this Surprise Lake that's the blue of you know of like a gemstone and right next to it you have this yellow and red hot spring pouring into it and it's just -- I still have the, the picture as my screensaver on my computer because I never tire of it.

CURWOOD: Is there another memory you have from there that you would like to share that’s sort of incredible?

Orange lava flows and hot springs speckle the bottom of the caldera, bleeding into Surprise Lake. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: You know, one of the -- [LAUGHS] this might not be the kind of experience everyone wants, but we rounded a curve in a bay as we were exiting the monument. And around the corner, maybe a couple hundred yards away, was a, was a brown bear who was snuffling around, maybe he was on a kill, we couldn't tell. And he headed up on to the bluff where there was a lot of alders and underbrush and we couldn't see him anymore. That's not great because you want to keep an eye on the bear. So we decided to cut the corner across the bay and just walk through the tide flat and keep our distance. So we took off our shoes and started walking across the tide flat and the tide flat turned out to be almost thigh deep with tidal mud. So now we're reduced to walking at about one step every four or five seconds, as the mud is just sucking at our bodies. Meanwhile, we can hear the bear 150 yards away chuffing, you know, making unhappy noises in the underbrush. And then we get to the other side of the, of the bay. And the guide encourages us to walk as fast as possible. And I notice that he has drawn Pepe, the 44 Magnum, which encourages you to walk even faster. And we get to the other side of the brush. And we have no idea where the bear is. And there's a small path through the woods that we have to take. There's no alternative. And it turns out that it's what's called a bear trail. And these bear trails are these habitual paths that bears use for years, sometimes a century, sometimes longer. They're just, they're bear highways. And it was so well used by bears, by these thousand-pound bears, that the bear trail was knee deep with use. It was so worn. So we're walking through this incredibly dense thicket. We can't see 10 feet in front of us, with gun drawn, screaming and yelling 'hey bear!' 'Hey, bear!' with no idea where the bear is. And then we pop out on the other side safe. And we inflate our little rafts, and we float across a bay. And there's whales diving and puffins flying, and it was just a great end after a lot of adrenaline. So, [LAUGHS] It's the kind of thing that, you know, makes the colors a little brighter in life.

CURWOOD: How worth it was it to go?

Brown bears are highly abundant within Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

SOLOMON: For someone like me who values wilderness, and solitude, and adventure, and who is willing to endure a little bit of discomfort and sogginess and freeze dried food [LAUGHS] for that payoff. It was a memory of a lifetime. And if you too are of that bent, I would encourage it highly. In 10 days, we saw two other people and they were fishermen who had simply pulled up on shore to just poke around for a few minutes. Otherwise we saw, we saw more bears than people; we saw beauty that I still tell people about. I made some friends for the rest of my life. I do find, and as I've written elsewhere, that the few people you go out with on these kind of experiences, these kind of wilderness experiences, have a way of really sharpening the relationships among the people that one spends time with. In short, it was one of better experiences of my life.

CURWOOD: Chris Solomon is a contributing writer for The New York Times and Outside Magazine. Chris, thanks so much for joining us today.

SOLOMON: Oh, it's my pleasure. Thank you.

CURWOOD: And, I'm glad the bears didn't get ya.

SOLOMON: [LAUGHS] So am I!

Chris Solomon is the Society of American Travel Writers 2018 Travel Writer of the Year. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Solomon)

Related links:

- Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

- Outside | “Baked Alaska: Surviving Aniakchak National Monument”

- Chris Solomon’s Website

[MUSIC: Ray Charles, "America The Beautiful" on Ray Charles Forever, Concord Music Group]

CURWOOD: Coming up. Going vegan when the rest of the family isn’t. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chris Belleau, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” on Swamp Fever, by Charles Mingus (Chris Belleau/Proud Dog Records)]

BirdNote: Exquisite Thrush Song

A Hermit Thrush coos on the branch of a coniferous tree. (Photo: Mike Hamilton ©)

CURWOOD: In nature all creatures are beautiful in their own ways, even if we don’t always understand or appreciate them. But there is one genus of birds that has some of the easiest songs for humans to love, as Michael Stein tells us in today’s Bird Note.

[Wood Thrush song]

STEIN: Some believe the song of the Wood Thrush to be the most beautiful bird song in North America.

[Wood Thrush song]

Others select the song of the Hermit Thrush.

[Hermit Thrush song]

Still others name the singing of the Swainson’s Thrush.

[Swainson’s Thrush]

STEIN: So how do thrushes create such fine music? The answer is that the birds have a double voice box. Bird song emanates from a complex structure, unique to birds, called the syrinx. Syrinx is also the Greek word for the musical instrument we call panpipes, which have multiple pipes. It’s a fitting name for this essential part of a bird’s vocal anatomy, because, like panpipes, birds have two separate pipes to sing with. A fine singer like a thrush can voice notes independently and simultaneously from each half of its syrinx, notes which blend brilliantly as ethereal, harmonious tones.

A Wood Thrush sings on the muddy banks of a small body of water. (Photo: Greg Miller ©)

[Hermit Thrush song]

Fortunately for us, the results are lovely and haunting.

[Wood Thrush Song]

I’m Michael Stein.

[Wood Thrush song]

CURWOOD: For photos of these songsters, wing your way to our website, loe.org.

And by the way, the wood thrush typically migrates north to the US in Early April from wintering grounds in tropical forests from southern Mexico to Colombia. Over the past several decades, the wood thrush population has declined by 60 percent or more, with the loss of habitat cited as the major culprit. But you can still hear them today, mostly after the leaves come out in the Eastern deciduous forests.

And for your listening pleasure, here’s a longer recording of a wood thrush that Lang Elliot made on a late April day in a deep ravine in the Smoky Mountains, as part of his series Music of Nature.

[Wood Thrush Song]

Related links:

- Listen on the BirdNote Website

- More on how songbirds produce their tunes

- Music of Nature: “Wood Thrush, Flautist of Nature” by Lang Elliott

[Wood Thrush Song]

Vegan Generation Gap

Paloma cooking with her mother, Marcia Fontes. (Photo: Courtesy of Paloma Beltran)

CURWOOD: More and more people today are choosing to eat less meat as a way to take better care of the planet and themselves. But Living on Earth intern Paloma Beltran says it’s not always easy.

BELTRAN: One of my favorite things about visiting my family is my mom’s cooking.

My mom, to me, is an undiscovered celebrity masterchef. Her name is Marcia, and she is definitely the cook of the house. It’s amazing how everything she makes comes out tasting so good, like from a five star restaurant. I have always praised her culinary skills, I’m like her number one fan.

So when I went vegan it was a much harder job for her. I stopped eating a lot of her food because it contains dairy or animal products. She uses this seasoning called norswisa, which is made up of ground chicken – it basically contains the waddle, the beak, the legs… It’s a very common seasoning in Mexico.

So I was a little bit hesitant to continue eating her food, even though she claimed it was 100% vegan -- but I still did. Until one day – I caught her in the act. She was sprinkling some norswisa into a veggie broth. After that, I completely stopped eating her food, for months. And she was heartbroken.

Ratatouille is a dish that can be easily made using all vegan ingredients. (Photo: benmillett, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It took her a while to try and incorporate vegan ingredients. I really didn’t expect her to, but she wanted to; very sweet of her. We started working together on vegan recipes -- things we could share. One of our favorite dishes is ratatouille. It’s very simple to make.

It basically consists of eggplant, cebolla, tomates, tomato paste, vegan butter, ajo, and fresh parsley. You’d start off with a Pyrex and at the bottom you’d put butter, onions, and salt and pepper. Then you’d soak slices of the berenjena in water, that way it softens up.

Once the eggplant is softened you can start making layers: of berenjena, tomato, onions, tomato paste, and seasoning. You’d continue making layers up to the top of the dish. Once you got to the top you’d sprinkle some fresh perejil, and then pop it into the oven, around 350 degrees. You’d leave it there until it’s softened up, and everything harmonizes. And that’s our favorite dish.

[MUSIC: Pete Seeger, “We Shall Overcome” on The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, Written by Charles Albert Tindley, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings]

An Afternoon with Pete Seeger

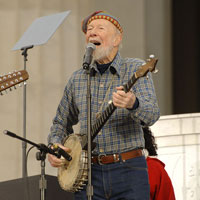

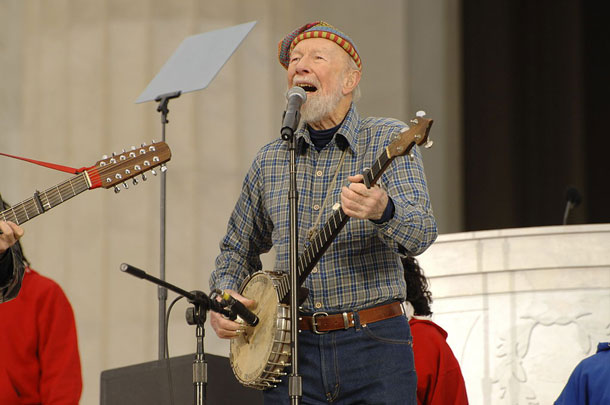

Pete Seeger was a legendary American folk singer and activist. (Photo: Donna Lou Morgan, U.S. Navy, Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Back in the 1940’s Radio station WNYC in New York featured the music of a tall banjo-and guitar playing man named Pete Seeger. He became an icon of the post World War Two folk music scene and also a social and environmental activist and won a lifetime Grammy. Pete Seeger was born almost exactly 100 years ago, so we thought this would a good opportunity to feature a piece we did when we spent an afternoon with him a few years back.

[AUDIENCE CLAPPING]

SEEGER: [SINGING] I've lived all my life in this country.

I love every flower and tree.

I expect to live here till I'm 90.

It's the nukes that must go and not me.

AUDIENCE: [SINGING] It's the nukes that must go and not me.

The nukes that must go and not me.

I expect to live here till I'm 90.

It's the nukes that must go and not me.

CURWOOD: That's Pete Seeger leading a crowd in an anti-nuclear song at a Harvard University gathering back in 1980. For some in the audience, this may be the apex of their protest days. For Pete Seeger, it's another night on the town as the nation's troubadour of conscience. America's tuning fork, some call him. For more than half a century, Pete Seeger has been leading people throughout the world in song, and in the process he's become a walking history of folk music and social activism. In the 1930s and '40s, you'd find him and his famous banjo on the union picket line.

SEEGER: [STRUMMING BANJO] Now you want higher wages, let me tell you what to do.

Got to talk to the workers in the shop with you.

You got to build you a union, got to make it strong.

But if you all stick together, boys, 'twon't be long.

You get shorter hours. Better working conditions.

Vacations with pay, take the kids to the seashore...

CURWOOD: Singing songs with outspoken political views led Pete Seeger in 1955 to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Congress wanted him to testify about alleged Communist affiliations. Name names, it was called. Mr. Seeger refused, was ordered to jail, and blacklisted. An appeals court blocked his prison term, and Pete Seeger kept on singing. In the 1960s it was songs for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam.

SEEGER: [SINGING] The sergeant said, "Sir, are you sure this is the best way back to the base?" "Sergeant go on, I fought at this river about a mile above this place.

It'll be a little soggy but just keep sloggin', we'll soon be on dry ground.

We were waist deep in the big muddy, the big fool says to push on...

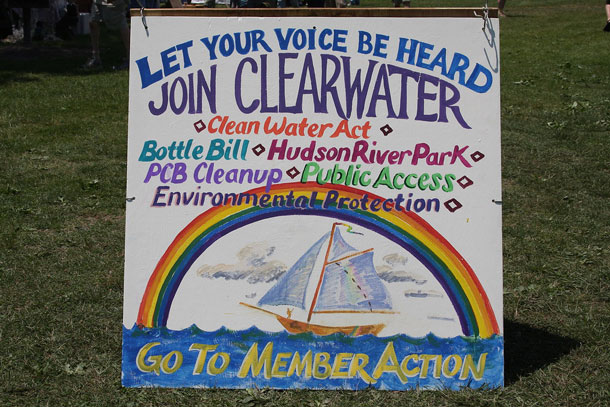

CURWOOD: And ever since then it's been the environment. In 1969, with the help of other musicians and activists, Pete Seeger built a sloop he christened the Clearwater, because that was his intention: to clear the waters of the Hudson River of pollution and garbage.

Pete Seeger, his wife Toshi and friends founded the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc. to help combat the pollution in the Hudson River. (Photo: Flickr, Jim the Photographer CC BY 2.0)

Pete Seeger lives on the Hudson, in a small quiet town called Beacon, about an hour north of New York City, and just 30 miles from where he was born. For decades, he and his neighbors have met on the river's banks at the Sloop Club to socialize and organize over potluck suppers. He's asked us to meet him there, where it's his turn to set up for this month's gathering.

A bright red pickup truck loaded with logs and plywood pulls up. A tall, wiry man with a white beard and glasses jumps out.

[DOOR SHUTTING]

SEEGER: Hope you haven't been waiting too long.

CURWOOD: Nope, how are you?

Pete Seeger has lived eight decades, but he moves with the ease and energy of someone who still has a lot to do.

[TO SEEGER] Mr. Seeger, you got here a Ford Ranger, except it didn't make much noise when you pulled up.

SEEGER: I bought it for $8,000. A schoolteacher who teaches electricity wanted to learn more about electric cars, so he made his own electric car. And he put into it a 28-horsepower electric motor, and 20 6-volt batteries.

CURWOOD: Can I see under the hood?

SEEGER: Sure.

[HOOD OPENS]

SEEGER: Not much here.

CURWOOD: Nope. Except a sign that says, "Caution, wear rubber gloves. You could be electrocuted." [LAUGHS]

SEEGER: Right. There's like 400 amps. For me it's perfect. I live on a very steep mountainside and I'm always carrying rocks and logs, and with a low range and 4-wheel drive I can inch up the steepest kind of slope with a ton of logs. It can go a foot a minute if I want to go that slowly, because I just feed in more or less power with the accelerator. I'd be burning out the clutch if I was using a regular gasoline car.

CURWOOD: Let's go over here by the...your dock’s here out of the water and we can chat a bit. What a place for a sunset, huh?

[WATER LAPPING ON SHORE]

SEEGER: This waterfront was a tangle of weeds, and the river was like an open sewer 30 years ago when the Clearwater started. And little by little it's gotten better. That park over there was our big victory. We petitioned and petitioned and people laughed at us, but, by gosh, the petitions finally had an effect. And a little city money and a lot of federal and state money - a million dollars to make a park out of seven and a half acres of garbage.

CURWOOD: Aha. Pete Seeger, how'd you get involved in environmental concerns?

SEEGER: It was Rachel Carson's famous book "Silent Spring." I read it in The New Yorker, in installments. Up to then, I'd thought the main job to do is help the meek inherit the Earth. And I still, that's a job that's got to be done. But I realized if we didn't do something soon, what the meek would inherit would be a pretty poisonous place to live. And so I made almost a 180-degree turn, started reading books like "The Population Bomb" by Paul Ehrlich, or "The Poverty of Power" by Barry Commoner. I'm a readaholic. And I was reading a book about the sailboats that sailed here, oh, all during the 19th century. Alexander Hamilton wrote one of the Federalist Papers on his way to Poughkeepsie in a sloop, where they were arguing whether or not to sign the Constitution idea and agree to it.

Cleaning up the Hudson River was a key mission for Pete Seeger. (Photo: Flickr, Kalyan CC BY-SA 2.0)

Well, I write a letter to my friend: wouldn't it be great to build a replica of one of these? Probably cost $100,000. Nobody we know has that money, but if we got 1,000 people together we could all chip in. Maybe we could hire a skilled captain to see it's run safely and the rest of us could volunteer. And three years later the sloop Clearwater was built up in Maine, and I helped sail it down with Don McLean and a batch of other singers. And now it takes school kids out. It's not a rich man's cruise boat. Two or three times a day it takes groups of 50 school kids out, teaches them what makes rivers dirty and what's got to be done to clean them up. Of course, people say what can a sailboat do? It can't do much except bring people together. But when people come together, that's when miracles happen, right?

CURWOOD: What do you think it's done for the river?

SEEGER: It drew attention to it in such a friendly way that people couldn't help getting attracted. In the little town of Cold Spring south of here, there were some very conservative people who thought it was a communist, treasonous project, because I was involved with it.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Aren't you communist, Pete Seeger? [LAUGHS]

SEEGER: I told people at age seven I became a communist when I read about American Indians. And anthropologists, that's the term they use for the way our ancestors lived anywhere in the world. The men hunted, the women gathered berries and dug for roots and carried babies on their back. And somebody killed something to eat, the meat was shared. That's communism. I admit, it seems romantic to want to go back to that, but I really do believe that if there is a world here, if there's a human race here in 100 years, we will have learned how to share again.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

SEEGER: Well, down in this little town, a man came down to see the Clearwater, and he beckoned to me. He said, "Seeger, can I talk to you a minute?" I said, "Sure." He said, "I don't want you to think I agree with you, not one-tenth of one percent, but that sure is a beautiful boat." He couldn't take his eyes off it. [CURWOOD LAUGHS] 160-foot tall the mast goes up. I call it a symphony of curves. There are hardly any straight lines on a sailboat and very few right angles. Curves, curves.

[SINGING WHILE PLAYING GUITAR]

Sailing down my golden river.

Sun and water all my own.

Yet I was never alone.

Sun and water are all life givers.

I'll have them where'er I roam.

And I was not far from home.

SEEGER: That was the first Hudson River song I wrote. The Clearwater had not been built. I hadn’t even thought of the idea. I was sailing a little plastic boat and there I looked at the water beneath me. There was lumps of this and that floating by with the toilet paper. And the phrase of John Kenneth Galbraith came to mind. “Private affluence, public squalor.”

I had money to buy this little plastic boat. We had money to go to the moon. But we didn’t have money to keep the rivers clean. And later on, I was sailing by myself and I saw the sun go down and the sky turned from yellow, to pink, to purple, to midnight blue, and I had [SINGING] sailing down my golden river, sun and water all my own, but I was never alone.

[GUITAR STRUMMING]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back with more music and conversation from Pete Seeger in just a minute or so. So keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pete Seeger: “One Percent Phospherous Banjo Riff” from 89 (Appleseed Entertainment 2008)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Back now to our Afternoon with Pete Seeger, recorded in 1988.

[GUITAR STRUMMING]

CURWOOD: Let's talk about some other songs. Garbage.

SEEGER: This was written by a young fellow named Bill Steele who has for years been the head of the folk song club up in Ithaca, New York. But he wrote it in San Francisco when he was visiting there, and it became an underground hit. There must be thousands of people all around the country who know this song and sing it. I added a verse. A friend of mine had written the first part of the verse: [SINGS]

In Mr. Thompson's factory they're making plastic Christmas trees.

Complete with silver tinsel and a geodesic stand.

The plastic's mixed in giant vats from some conglomeration

That's been piped from deep within the Earth or strip-mined from the land.

Well, then he went on to say and so the water gets dirty in Long Island Sound, but I changed the words: [SINGS]

And if you question anything they say why don't you see?

It's absolutely needed for the economy.

Garbage, garbage, garbage,

Their stocks and their bonds, all garbage.

What will they do when their system goes to smash?

There's no value to their cash.

There's no money to be made.

But there's a world to be repaid.

Their kids will read in history books

About financiers and other crooks,

And feudalism and slavery and nukes and all their knavery.

To history's dustbin they're consigned along with many other kinds of garbage, garbage, garbage...

You know, I drew blood with that verse? I sang it on “The Today Show” once, and Fortune magazine says, "Esso was sponsoring that program. Do they know what songs are being sung with their money?" [CURWOOD LAUGHS] And they quoted the verse I'd sung. I don't necessarily like to draw blood. I'd rather persuade people to laugh and eventually agree that maybe I've got a little right on this side.

Incidentally, the only way I got it on “The Today Show” was by -- I have to confess -- a little bit of devious preparation. I knew that NBC wouldn't be happy about me singing it. I come in at 6:30 in the morning; they say, "Pete, what are you going to sing?" I said, "Well, I've got a cheerful little banjo tune; I've got something else a little more serious." "Well, let's hear them." Played the banjo tune. "Fine, what's the other?" I sang “Garbage.” They say, "Well, Pete, it's a little early in the morning. You got something else?" I was prepared. I sang [SINGS}: Walking down death row...

They say, "Pete, you got something else?"

[SINGS] If a revolution comes to my country...

“Well, Pete, I guess we better stick with ‘Garbage.’” [CURWOOD LAUGHS] The whole studio broke up: the cameraman, the prop man: yes, we'll stick with “Garbage”!

[SINGS]: Mr. Thompson starts his Cadillac,

Winds it down the freeway track,

Leaving friends and neighbors in a hydrocarbon haze.

He's joined by lots of smaller cars all sending gases to the stars,

There to form a seething cloud that hangs for 30 days.

And the sun blinks down into it with an ultraviolet tongue,

Turns it into smog, then it settles in our lungs.

Oh! Garbage, garbage garbage...

We're filling up the sky with garbage.

What will we do when there's nothing left to breathe but garbage?...

Woody Guthrie was good friends with Pete Seeger. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: You've spent a lot of time with Woody Guthrie. I'm thinking of Woody Guthrie's song “Roll On Columbia” in which he speaks in such glowing terms of the dams that are there.

SEEGER: Yeah. I think if Woody was around now, he would find some funny song. He was wonderful at combining tragedy and humor, all in one song. He did have a funny verse: Them salmon fish are pretty shrewd. They've got politicians, too. Run every four years. [CURWOOD LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: What's the most important thing when it comes to the environment?

SEEGER: I tell people, work in your local community. The world's going to be saved by people who fight for their homes. Now, there may be glamorous places to go to, far across the oceans on, but really the world's going to be saved by people who fight for their homes.

CURWOOD: Is there a song that you'd like to talk about in connection with, you know, working in your own community, working in your town, to make the environment better?

SEEGER: Well, a lot of songs are about it. [SINGS]

Inch by inch, row by row,

Gonna make this garden grow.

It's “The Garden Song,” written by a fellow up in the state of Maine, and Arlo Guthrie and I and lots of others have recorded it. I've also written a little song I sing on the general subject of praying, because I think church people and non-church people should find ways to get together. It was just about a year ago, a little over a year ago, I was out getting wood to start the morning fire. We heat our house with wood. And I look up and see the sun poking itself up over the mountain. [SINGS] Early in the morning, I first see the sun,

I'll say a little prayer for the world.

Hope all the little children live a long, long time.

Every little boy and little girl.

Hope they'll learn to laugh at the way some precious old words seem to change,

'cause that's what life is all about: to arrange and rearrange and rearrange.

And I have a little chorus: [SINGS]

Oh, whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

You get the audience singing it.

CURWOOD: Come on, you guys. [LAUGHS]

Steve Curwood and Pete Seeger during the recording of the April 17th, 1998 Living on Earth broadcast “An Afternoon with Pete Seeger” (Photo: Eileen Bolinksy)

SEEGER: You'll have to help me out, next time. It's like a zipper song; anything nice that happens you can have a new verse. For me, it was ten and a half years ago, one A.M. our son-in-law Shabazz knocks on the door: "The baby's coming!" I said ‘have you called the midwife?’ "Yes, yes, she's bringing two friends."

Well, so we called up a couple friends. It was a party for three and a half hours. Our daughter beamed like she was in heaven, and on occasion she'd let out a shriek and then beam some more. And after three and a half hours her firstborn, who was six years old at the time, says, "I see the head! I see the head!" [SINGS]

Heard the first yowl of a brand new baby,

And I said a little prayer for the world.

Hope all the little children live a long, long time,

Yes every little boy and little girl. [CLAPS]

Hope they'll learn to laugh at the way some precious old words do seem to change.

'Cause that's what life is all about: to arrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Sing it with me.

BOTH: [SINGING] Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

SEEGER: [SINGS]

Well, sometimes I wake in the middle of the night

And rub my achin' old eyes.

Is that a voice from inside my head,

Or does it come down from the skies?

There's a time to laugh but there's a time to weep,

A time to make a big change: wake up, ya bum!

The time has come to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Sing it again!

BOTH: [SINGING] Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

[LAUGHS]

SEEGER: I've tried to write lots of songs, but I have to admit that it's one thing to try and write a song and another thing to write one good enough for people to want to remember and sing. Woody Guthrie wrote 1,000 songs and there's maybe a dozen which will be widely sung. And a friend of mine had started a small record company, and he says, "Pete, would you be able to put out a record of some of your own songs?" I said, "My voice is gone, it's too wobbly, too raggedy.” When I stand on a stage mainly what I do is get the audience singing; I accompany them. I line out the hymn, as they say in church. But he says, "What if I get other people to sing them?" I said, "Fine, if you can find them." Well, by gosh, he got some awful well-known singers: Bruce Springsteen and Bonnie Raitt and Billy Bragg and Judy Collins and a whole lot of others, put out 2 CDs, mainly of songs that I wrote. And other songs like “We Shall Overcome.” All I did was make an arrangement of them.

Pete Seeger passed away on January 7th, 2014 at the age of 94, but his legacy lives on. (Photo: Flickr, Jens Schott Knudsen CC BY 2.0)

SPRINGSTEEN: [SINGS] Hey, we shall overcome.

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day.

Darlin', here in my heart, yeah I do believe

We shall overcome some day.

Well, we'll walk hand in hand.

We'll walk hand in hand...

SEEGER: That's an interesting story. Did you know that there's an old gospel song, quite well known, [SINGS AND CLAPS] "I'll overcome. I'll overcome. I'll overcome some day..."

Well, 300 women were on strike in 1946. It was in winter and I guess on the picket line they probably had a barrel with a little fire in it, and people were warming their hands and singing old gospel songs to keep their courage up. And one woman, Lucille Simmons by name, loved this song, but she sang it, what they call long meter style. And she changed one word. "I'll" became now "we." And she sang, [SINGS SLOWLY] "We will overcome."

Now church people know how to harmonize, and the basses get the low notes and the sopranos get the high notes, and you weave in and out. And a group of people can make beautiful music just improvising with each other. It became one of their favorite strike songs: we will overcome some day.

Well, a white woman, a union organizer, Zilphia Horton by name, she learned it from the strikers, it became her favorite song. Anyway, I spread the song around the country, but I didn't have a good voice like that, those two women, so I gave it a banjo accompaniment: omm, chinka oom, chinka oom chinka omm, chinka oom, chinka oom... I got audiences in town hall and others singing it, but it didn't really spread -- until 1960, a young friend of mine, Guy Carawan by name, had a workshop called “Singing in the Movement.” And some 70 young people from Texas to Florida to Virginia gathered at that little Highlander School and swapped songs for a weekend and made up new verses and so on. And when Guy taught them this song, they said, "Oh, Guy, you got a song here!" And Guy had started giving it a kind of rhythm, which now everybody knows. It's...musicians call it 12/8 time, that is, four beats, but each four beat is divided up in three little beats...one two three, one two three, one two three, one, two, three, four...

SEEGER [CLAPPING AND SINGING WITH AN AUDIENCE]:

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day.

Oh, deep in my heart, I know that I do believe,

Oh we shall overcome, someday.

We shall live in peace!

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace some day.

Ohhh, deep in my heart I do believe we shall overcome someday.

The whole wide world around!...

[TO CURWOOD]: Saving the world is not going to be easy. It's going to require huge arguments. People who call themselves environmentalists don't always agree. One says, "Don't have any dams," but along comes a man and says, "If you have a lot of small dams they won't do any damage, or not enough, and saves burning fossil fuels." Who knows what's going to happen?

All I know is I wish I could live another 30 or 40 years, because some of the most exciting things are going to happen. When I meet people who say, "Oh, there's no hope, Peter, look at the things that are going wrong, and those stupid people in Bosnia, there are going to be things like that all around the world, where power-hungry people says 'I know how to handle this, just give me the bomb.' There's no hope."

But I say to them, I said, "Did you think that our great Watergate president would leave office the way he did?" "No, I guess I didn't think that." I said, "Did you think that the Berlin Wall would come down so peacefully?" "No, I didn't think that would happen, yeah." I said, "Did you think Mandela would be president of South Africa?" "No, I didn't predict that." "Well, if you couldn't predict those three things, then don't be so confident that there's no hope." And I give them a bumper sticker. It says, "There's No Hope, But I May Be Wrong."

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

[SEEGER STRUMS GUITAR]

CURWOOD: Pete Seeger, thanks so much for taking this time with us on Living on Earth today.

SEEGER: Thank you for inviting me.

CURWOOD: What's it say on your banjo here? It says...

SEEGER: "This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender." I hope.

On Pete Seeger’s banjo it says “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender.” (Photo: Flickr, Jim the Photographer CC BY 2.0)

[STRUMS GUITAR AND SINGS]: Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well may the world go when I'm far away.

Well may the skiers turn, the swimmers churn, the lovers burn.

Peace may the generals learn when I'm far away. [SINGS WITH OTHERS]

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO MUSIC]

Sweet may the fiddle sound, the banjo play, the old hoe-down,

Dancers swing round and round when I’m far away.

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO BRIDGE]

Fresh may the breezes blow, clear may the streams flow,

Blue above and green below when I’m far away.

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO BRIDGE]

CURWOOD: Pete Seeger, sadly now very far away - but if the world goes well, it's at least partly thanks to his banjo, his optimism and his hard work. We bid him a very fond farewell. Thanks for everything, Pete.

SEEGER: Yes - well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Every week we put together a newsletter for you, the listeners to Living on Earth. There you can have an insider’s look at the people and ideas that come together to make this program. And right now you can even give us some advice. When you sign up for the newsletter you’ll be invited to complete a survey to tell what you think about our program. Just go to loe.org to subscribe where it says newsletter.

Related links:

- Learn more about Pete Seeger and his legacy

- Learn more about the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, Inc

[MUSIC: Pete Seeger, “Banjo Medley: Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss / Cripple Creek / Ida Red / Old Joe Clark”, on The Smithsonian Folkways Collection, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Meralin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google play, and like us, please, on our Facebook page, PRI’s Living on Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth