August 9, 2019

Air Date: August 9, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

No-Show Green Voters

View the page for this story

About 20 million registered voters in the US list the environment as one of their top two priorities. But compared to other voters they’re more likely to stay home on Election Day. These "super-environmentalists" are also more likely to be in a minority group -- they're often African-American or Hispanic -- and they tend to be young and live in cities. Founder of the Environmental Voter Project, Nathaniel Stinnett, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what it might mean for environmental policies if these 20 million "super-environmentalists" registered voters actually show up at the polls in greater numbers and what his organization is doing to get out that green vote. (11:29)

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson, Arizona is the latest subject of Living on Earth’s occasional series on America’s public lands. There’s plenty of heat and cacti, of course, but also many species ordinarily found far north of the desert Southwest. With a local biologist as her guide, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on the remarkably diverse biomes of Arizona’s Sky Islands. (11:01)

BirdNote®: Ponderosa Pine Savanna

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The unique ecology of the ponderosa pine savanna, which covers much of the desert Southwest, has been shaped in large part by fire. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more about the birds that call this landscape home. (01:52)

Fighting Climate Change, Naturally

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Climate mitigation often focuses on technical solutions. But experts say as much as one-fifth of the United States’ current carbon emissions could be offset through “natural climate solutions,” which manage and restore land. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill reports. (03:03)

Free the Beaches: Desegregating America’s Shoreline

View the page for this story

The US civil rights movement to end racial segregation in the 1960’s may have been most intense the South, but there were battles in the North, including in the State of Connecticut. Just about all of the Long Island Sound beaches in Connecticut were off limits to people of color until Ned Coll came along. In his 2018 book Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline, historian Andrew Kahrl describes Coll’s creative protests to smash the color bar and let all children cool off on hot days at the beach. He spoke with host Steve Curwood. (17:22)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Andrew Kahrl, Nathaniel Stinnett

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Mary McCann, Aynsley O’Neill

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

With the presidential primaries coming on the horizon, motivating voter turnout is key to getting climate action, activists say.

STINNETT: Politicians go where the votes are. And so if you get more environmentalists to vote, any politician, whether they're liberal, conservative, or in the middle, they're going to pay attention, because they're in the business of winning elections

CURWOOD: Also, an oasis of cool in the hot desert of the American Southwest.

AVILA: When we are at 110 degrees down in Tucson, you can come up here and be at a nice 70 or 75 degrees. And so yeah, the sky islands are this amazing mix of desert and mountains and little treasures. You might go into one of these canyons and find a little creek or something and see something that you didn't expect to see.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

No-Show Green Voters

The Americans who care most strongly about the environment are more likely to be African-American or Hispanic, make less than $50,000 a year, and live in cities. These populations are among those most affected by environmental justice issues – and tend to vote less often than other demographics. (Photo: Becker1999, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Surveys show the majority of registered voters who say the environment is a top priority for them didn’t bother to cast a ballot in the 2018 US elections. To increase the turnout of environmentally concerned voters and thus influence environmental policies, the non-partisan, non-profit Environmental Voter Project was founded. Nathaniel Stinnett is the Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project, and we’ve been following his work. His group tried an experiment to increase turnout among green-focused registered voters in the midterms and he is with us today to discuss the results.

Nathaniel, welcome back to Living on Earth!

STINNETT: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Remind us, please, of your criteria. How do you determine if a voter is what you call an environmental voter?

STINNETT: So we have a very stringent set of criteria. We are only going after people who care so deeply about climate or other environmental issues, that it's their number one priority, over all others, or their number two priority. So these are people we like to call “super-environmentalists”.

CURWOOD: And, demographically, who's most likely to be a “super-environmental” voter?

STINNETT: Well, it's not who you might think. It's not yuppies, in fleeces, jumping out of their Priuses. It is far more likely to be Latinos, African Americans, often people who make less than $50,000 a year, and usually people who live within five or 10 miles of an urban core. With each passing year, this is increasingly a population of poor people, and people who tend to be part of minorities.

CURWOOD: Why do you think so many people of color are in this category of being super-environmentalists?

STINNETT: People of color and poor people are far, far more likely to be on the front lines of climate change, of air quality issues, and water quality issues. So it should come as no surprise to us that the people who care most about these issues are the ones who are being impacted the most by these issues.

CURWOOD: And at the same time, these people don't vote so much.

STINNETT: That's right, they don't. The environmental movement does not have a persuasion problem. There are tons of people who care deeply about environmental issues. We have a turnout problem, we're not showing up on election day. And it's starting to get a little bit better, but it's not getting better fast enough.

CURWOOD: So what do you think it is that holds people back?

STINNETT: We don't know for sure. But let me tell you what we do know, because we know some of the reasons why these people aren't voting. One reason is, as we discussed previously, we know that if you deeply care about the environment, you're more likely to be Latino, African American, poor, and probably young. And those four groups that I just mentioned, they tend to vote less often than the general electorate does. So part of what's going on here is just a basic demographic correlation. But here's the really interesting thing, Steve, if you only look at Latinos, the ones who care about the environment vote less often than the other Latinos. If you only look at young people, the ones who care about the environment vote less often than other young people. So there's something else going on there. And I'm not going to pretend like we know what it is. We've researched it over and over and over again. And it's really hard to figure out. I can tell you some of the excuses that people give. Some people are saying, oh, politicians don't care about the issues that I care about. I think that's probably accurate. But you know how to change that Steve? Vote! Vote! [LAUGHS] So that's part of what we're trying to do here.

I think another thing that's going on is ballot access issues. In any state, where there are laws and regulations that are making it harder for people to register to vote, or harder for people to show up on election day, usually, those laws are making it harder for people of color or young people to vote. And those are the environmentalists. I think it's very important for the environmental movement to internalize this. We're getting better when we talk about environmental justice issues, to realize that environmental issues are often civil rights issues. But it goes the other way as well. Chances are, if there is any civil rights issue at play, it is also disproportionately impacting the environmental movement, because the environmental movement is disproportionately made up of people of color, poor people and young people. And so environmental groups really need to pay attention to ballot access issues. If there is a state that makes it harder for people of color to vote, that means that fewer environmentalists are voting, and that's hurting our ability to impact policymaking.

CURWOOD: Now, your organization focuses on increasing voter turnout, rather than campaigning for any particular candidate or issue. How exactly does that work?

Instead of advocating for particular candidates, the Environmental Voter Project focuses on turning out larger number of environmentally conscious voters at the polls. The EVP believes this is key to making politicians act on the climate crisis. (Photo: Marc Nozell, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

STINNETT: So, we essentially do two things: we focus on data science and behavioral science. So the first part of it is, we will poll tens of thousands of people to try to identify people who are these super-environmentalists we're talking about, people who care so deeply about climate or the environment, it's one of their top two priorities. Then, we don't talk to the people who are already good voters, they don't need our help, we only focus on the ones who aren't voting. And that's when we shift into the second part of what we do, which is behavioral science. We already know that these people are with us, Steve. So we're not trying to change their opinions about anything. We're just trying to change their behavior, we're trying to turn them into better voters. And the good news at that point is, we can afford to use whatever works, because we don't need to change these people's minds. And so we can take advantage of all of this great research, and just use the messaging that we know has the highest likelihood of getting their rear ends out the door on election day.

CURWOOD: And that is?

STINNETT: We try to take advantage of the fact that we are social animals, not rational animals. So instead of trying to rationally convince someone who cares about a particular issue of the value of their vote, instead, we send them letters telling them how many of their neighbors turned out last time there was an election. Or we used very normative categorical statements like 'real environmentalists vote', or we'll have a canvasser get someone to promise to vote, and then we'll follow up with that voter and we'll say, “Don't you want to be an honest promise-keeper? Follow through on your promise to vote!” We take advantage of these norms that we all buy into, because we've realize that we're not all walking around in a cost-benefit analysis, we're social beings.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about a particular place where you have used these techniques and how people responded.

STINNETT: So a perfect example is we were targeting almost 900,000 unlikely-to-vote environmentalists in Florida. And what we did was, we never tried to rationally convince them of the value of their vote. We never tried to tell them, hey, you care about the environment, or you care about climate change, this is why you've got to vote. We know from all of our previous work that that doesn't work. Instead, we worked with over 2000 volunteers to text and call and canvass these voters. And we sent them direct mail and we sent them digital advertisements. But all of them, all of the messaging, and all of those media, simply focused on these sort of normative, peer-pressure focused messages that I discussed. And you wouldn't think that that would make a big difference. You'd think, gosh, this is like, really juvenile messaging, you're essentially using everything we learned in fourth grade. And you'd be right to think that.

But the results were extraordinary. In Florida alone, we increased turnout 2.2 percentage points among the people we were targeting. And that might not sound like a lot to you. But we were responsible for adding over 17,000 brand-new environmental voters to the electorate in Florida. And what we know, Steve, I know this sounds cynical, but it's just the truth, is that politicians go where the votes are. And so if you get more environmentalists to vote, any politician, whether they're liberal, conservative, or in the middle, they're going to pay attention, because they're in the business of winning elections.

In 2016, the climate crisis was all but ignored in the presidential debates, but several Democratic presidential hopefuls for 2020, including Jay Inslee, have made the climate a priority for their campaigns. (Photo: Jay Inslee, Office of the Governor, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, we're talking at a time that the Democratic field of contenders for the presidency is fairly large. And that means in the early primary, relatively small numbers of votes can make a huge difference. The percentage or two can be huge in the early going.

STINNETT: Well, you're absolutely right, a percentage or two can be the difference maker. And I think we're seeing something really extraordinary go on in American politics right now. Because four years ago, in the Democratic primary, no one was talking about climate change and environmental issues. They weren't. And now, almost everybody is. Signing on to the Green New Deal is almost seen like a litmus test. You have particular candidates, like Jay Inslee, centering their entire presidential campaign around climate change, but you also have other candidates talking about it quite a bit. And this is really extraordinary. A Monmouth poll of likely caucus goers in Iowa, showed that they list climate change as their second most important priority, and environment and pollution as their fifth highest priority. So my advice for people running for president is, talk about this issue. It's what voters increasingly want to hear about.

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

But, there's a huge caveat here, Steve. We're not seeing that yet in the general election numbers. When you sweep in Independents, and Republicans and also ten millions of new voters of all persuasions who are going to vote in the general election, climate and environmental issues are at best sixth, seventh, eighth, on people's lists of priorities. And I think this is why you're seeing Democrats who are running for president on the stump in New Hampshire promote the Green New Deal. And then when they're back in DC in the well of the Senate, they don't sign on to it. And it's because they're trying to appeal to two different electorates at once. And I think this illustrates perfectly the importance of voting. Politicians go where the votes are. And they're starting to wake up to the realization that there are lots of climate voters in the Democratic primary. But they're also cognizant of the fact that there aren't yet enough climate votes in the general, and we need to change that.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel Stinnett is founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Thanks so much for taking the time, Nathaniel.

STINNETT: It was my pleasure. Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- The Environmental Voter Project Website

- The Guardian | “’We Need Some Fire’: Climate Change Activists Issue Call to Arms for Voters”

- Listen to LOE’s previous interview with Nathaniel Stinnett

[MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, ”All Or Nothing At All” on Ballads, Blue Thumb Records]

Exploring the Parks: Cactus and Snow in the Desert Sky Islands

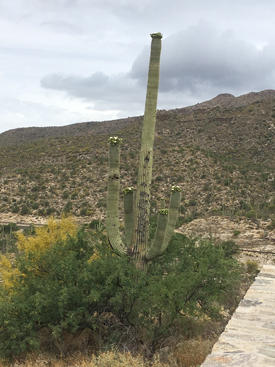

Coronado National Forest has an area of nearly 2 million acres spread throughout southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico, including the Sky Islands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, "This Land is Your Land" on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]

CURWOOD: More than 50 percent of Arizona is actually public land, a tapestry of state and federal land, including national parks and forests. That makes it an excellent destination for summer travels. I know what you may be thinking…. Arizona in summer time? No, thanks! Well, for this installment in our occasional series on public lands, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb visited the Coronado National Forest, north of Tucson and found the forest there is literally full of cool surprises. She went on a hike and drove up Mount Lemmon, roughly 80 miles north of the US border with Mexico. It’s a popular destination for locals and tourists alike.

[SFX CAR PASSES]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on the side of the road at the base of Mount Lemmon. It’s sunny and a pleasant 75 degrees. Sharp grasses and spiny succulents with bright yellow and pink flowers blanket the parched desert ground. I’m here with wildlife biologist Sergio Avila.

AVILA: We can see Sonoran desert plants and animals. We can hear right now some Cardinals, we can hear some Curve-billed thrashers, we can hear some mockingbirds.

BASCOMB: Sergio is outdoors coordinator for Sierra Club in the Southwest Region. Originally from Mexico, Sergio has thick black hair pulled back in a low ponytail.

AVILA: We are looking at the saguaros, which is the iconic, kind of descriptive plant of the Sonoran Desert.

BASCOMB: These saguaro cactuses stand sentry some 60 feet tall with large white flowers on each of their massive arms reaching upwards. I think the inventors of those cactus-shaped margarita glasses must have had the saguaro in mind.

The Saguaro cactus is an icon of the Sonoran Desert. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: So, for a plant like this, to have some arms, at least 250 to 300 years have passed for them to have their arms. So a lot of these saguaros that we see here are easily three, 400 years old, so they're ancient saguaros.

BASCOMB: Some of these cactuses may have been here when the Spaniards were establishing settlements. But Sergio says the native people of the area, the Tohono O’odham, have always had a close cultural connection with the saguaro.

AVILA: The new year, or the year for the Tohono O’odham starts on July 1st, and that is connected to when the fruit of the saguaro drops from the plant and around when the rainy season starts.

BASCOMB: And he tells me the fruits of the saguaro are an important food for everything from mice and skunks to foxes and coyotes. Their flowers provide pollen for a variety of bats and birds. The shallow roots are crucial for holding soil intact during the monsoon rains. And the body of the cactus itself provides housing for a number of residents.

AVILA: Saguaros are like apartment buildings with cavities, and so little owls, kestrels, woodpeckers, many other birds depend on saguaros to live inside of these cavities.

Sergio Avila is a wildlife biologist, as well as an outdoor activities coordinator with Sierra Club. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Unlike the Sahara, the monsoon rains pour on the desert here each summer, and scientists say that makes it this the wettest desert in the world. So even in the dry season, the Sonoran landscape is teeming with life. But as captivating as it is, there is so much more to see. So, Sergio and I pile into our car and head up the mountain.

[SFX CAR DOOR SLAMS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We drive around a bend in the road and suddenly the saguaro are gone. Within 1000 or so feet of elevation gain, it’s too cold for them.

[DRIVING SOUND 1-2 SECONDS]

We pass a scenic overlook, Tucson lies below us, and from here it’s clear to see why these are called sky islands.

AVILA: The sky islands, here in Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent parts in Mexico, are mountain ranges surrounded by grassland sort of deserts that make them look like islands.

BASCOMB: Back 15 to 20 thousand years ago, the climate of the southwest was much cooler and wetter. With the end of the last ice age, temperatures rose and desert came to dominate the landscape. But at higher elevations, temperate plants and animals were able to survive. Today those remnant biomes are marooned as mountain islands, surrounded by the sea of the desert.

Mount Lemmon. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: In this region of the sky islands, is the only place, or is the place where jaguars and black bears meet. It’s the place where you have northern birds like sandhill cranes, and birds from the tropics, like military macaws.

BASCOMB: The Sky Islands sit at the confluence of 4 different ecosystems, the Rocky Mountains to the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, and Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts. With so much diversity in one area, Sergio says, the sky islands are a biodiversity hotspot.

AVILA: So this biological region brings together a species from the north and the south that they don't meet in anywhere else.

[SFX CAR DOOR SHUTS]

BASCOMB: We get out of the car and walk along a small trail. The path we are on is actually part of the Arizona trail that goes from Mexico to Utah. We are driving up Mount Lemmon today but you can also hike the mountain in about 5 hours.

AVILA: I think right here we're at about 4500 feet of elevation. We've been going up on the mountain, and you can see a little bit of the change. Now we start seeing some oak trees. And I have to say, I'm pretty cold.

BASCOMB: I'm chilly.

AVILA: Yeah, yeah, let's go see what we see over here in the trees.

BASCOMB: We’re walking in an oak woodland, but dotted in the understory of a forest you might see in Pennsylvania are huge cactuses, waist high covered in orange and yellow flowers.

AVILA: This is a prickly pear. Eventually those flowers will turn into prickly pear fruit, which is a super juicy fruit that is a tremendous food source and water source for a lot of animals.

BASCOMB: It makes a good cocktail too.

AVILA: Oh, well I'm glad you mentioned that because part of the trip includes prickly pear fruit margaritas and that is a sky island staple. (laughs)

The Sky Islands are in the midst of four different ecosystems – the Rocky Mountains in the North, the Sierra Madre in the South, the Sonoran Desert to the West, and the Chihuahuan Desert to the East. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh perfect.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

AVILA: One thing I wanted to share, for example, this region has four different species of skunks.

BASCOMB: Really?

AVILA: Yeah, so it’s not, you know, just skunks, but we have striped skunks. We have spotted skunks, we have hog nose skunks, and hooded skunks.

BASCOMB: And are they all just as stinky?

AVILA: No! Those who are specialists in skunks actually say that different skunks smell different. Those who have experience with skunks can even tell one skunk species from the other from their smell. Which, you know, I think it's a level of skill that I don't know if I'm ever going to get to but…

BASCOMB: Do you really want to practice? [LAUGHS]

AVILA: Ah, exactly right. Like, what does what does it take to learn that? But it also speaks about … skunks, eat insects, skunks dig around for rodents, skunks might eat some reptiles. So the fact that we have four different species of skunks, in my mind says that we have a tremendous diversity of insects and rodents, and everything that is food for skunks, you know what I mean? We also have two different species of deer, white tail and mule deer, or black-tailed deer, that are adapted to a different elevation. We have four different species of cats in this region. The better-known bobcat, which is the short one with a short tail, and the mountain lion, or the cougar. And then the tree tropical ones, which are the ocelot, and the jaguar, the two spotted cats that come from the tropics. Having four species of cats, it's also an indication that we have a lot of different animals that can be food. And so the sky island region is a really good example of a whole ecosystem working together.

BASCOMB: So, these sky islands are a chain of mountains that start near San Javier, Mexico, 300 miles south of the border, and run into Aravaipa, Arizona, some 200 miles north of the international boundary. These mountains are a crucial corridor for migrating animals, like jaguar, that can migrate several hundred miles in search of territory and a mate. So, I ask Sergio how a high-security border wall could affect migrating wildlife.

Sky islands are mountains whose ecosystems are drastically different compared to their surrounding lowland environment. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

AVILA: You might be separating populations of carnivores, you might be separating populations of herbivores that are making use of some areas. And so this rich diversity in our region is very important. And it's one of the things that is under threat, short term by the border wall and other infrastructure there, and long term by climate change.

[CAR SOUNDS, DRIVING]

BASCOMB: Back in the car, we head up the mountain again. At about 7,000 feet of elevation, the oaks and cactus give way to pine trees. It looks exactly like a typical forest in New England. Around the corner we need to stop the car.

SERGIO: So we're looking at two white-tailed deer on the side of the road. They look like really young fawns. I would say these are young, from this last summer. I wonder where mom is.

BASCOMB: We peer into the thick vegetation, but don’t see mom, so once the deer are safely across we continue on to the top of the mountain to the Mount Lemmon Ski Valley. That’s right, alpine skiing in Arizona.

SERGIO: We are at 9000 feet of elevation in the ski area, the top of Mount Lemmon. We are surrounded by a meadow of aspen. If you've ever been in Colorado, you will recognize these trees very quickly. And we are in front of this ski lift and it is snowing. And here we are prepared for a field trip in the summer in Arizona and we are super cold.

Mount Lemmon reaches heights of over 9,000 feet and its summit area receives around 200 inches of snow every year. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: I'm wearing shorts and a sweatshirt and I'm uncomfortable. The thermometer in the car says it's 35 degrees up here. There’s snow sticking in your hair.

AVILA: Yeah. I also wanted to say we are seeing different birds, we saw a robin. Seeing different colored birds, but it is very gray and clouds are very dense. And so even the sound is kind of like hard… It’s not very noisy right here and so we only hear the wind blowing in the aspen trees. It is pretty, but it is cold.

BASCOMB: When we were driving up here we saw signs that say snow plow ahead and beware of ice, and that sort of thing.

SERGIO: And we were laughing at those signs on the road. Yeah, what did we know?

BASCOMB: We're not laughing anymore!

SERGIO: We’re not laughing anymore, no!

The trail map for Coronado National Forest, outlining the Sky Island Scenic Byway. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In terms of the climate and habitats, we’ve gone from Mexico to Canada in less than an hour. We warm up with some hot chocolate at the top of the mountain and then head back down the way we came. My ears pop with the sudden elevation change and I’m struck by the remarkable diversity one small mountain has to offer. And in the monsoon season, it’s different still, when a flush of life emerges to greet the rain and complete an entire life cycle in a matter of weeks. Far from the barren desert one might imagine, the Sky Islands of Arizona are full of surprises and well worth a visit nearly any time of year.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in the Sky Islands of Arizona.

Related links:

- Coronado National Forest

- Listen to Living on Earth’s most recent segment on the National Parks

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Ponderosa Pine Savanna

The Cassin’s Finch is right at home in a Ponderosa pine savanna. (Photo: © Tom Munson)

CURWOOD: Birders love the Sky Islands, where it’s one-stop shopping for both tropical and temperate birds, and BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more about the birds that call this landscape home, where fire can be a friend.

BirdNote®

Ponderosa Pine Savanna

[Western Meadowlark song]

We’re in a Ponderosa pine savanna.

A mountainside in Arizona’s Sky Islands shows a Ponderosa pine savanna, the result of a fire from several years prior. (Photo: Katja Schulz, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[Western Meadowlark song]

Tall pines with bark the reddish-brown of terra cotta dot an open, grassy landscape flecked with blue and yellow wildflowers. The warm air is fragrant with the spicy scent of resin. Dry pine needles crunch beneath your feet.

[W. Bluebird calls]

A Western Bluebird flits from a gnarly branch, as a Cassin’s Finch belts out a rapid song.

[Cassin’s Finch song]

The trees here grow singly or in small stands, making it easy to walk through and admire this Western landscape. Upslope, the pines become denser, mixing with firs. Downhill, the trees give way to an open grassland, where a Western Meadowlark sings.

[Western Meadowlark song]

The Western Meadowlark favors the open grassland of a Ponderosa pine savanna. (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

The open structure of this savanna, found on mountain slopes from the Rockies to the Cascades, results from recurring natural fires. Fast-moving blazes sweep through, burning the low vegetation but sparing the larger trees, which are protected by very thick bark.

After a fire, grass and wildflowers re-grow quickly, helping ensure that the meadowlark’s song will continue to ring across the hillside.

[Western Meadowlark song]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Sounds of the birds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Western Meadowlark: 23045 recorded by W.R. Fish; 106608 by R.S. Little and 137513 by G. Vyn; Western Bluebird 44896 by G.A. Keller; Cassin’s Finch 50197 and Pygmy Nuthatch 119403 by G.A.Keller.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2017 Tune In to Nature.org May 2017/2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# savanna-01-2012-05-11 savanna-01

https://www.birdnote.org/show/ponderosa-pine-savanna

CURWOOD: For pictures, head on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Learn more on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Walking In Two Worlds” on Southwest, Cheshire Records]

Fighting Climate Change, Naturally

Some of the most effective natural climate solutions include the restoration of forests, wetlands, grasslands and other ecosystems. (Photo: Pacific Southwest, Region 5, US Forest Service, USDA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: A lot of talk about tackling climate change focuses on technical solutions, like fuel-efficient cars and solar panels. But, there are also so-called “natural climate solutions,” which focus on better management of our ecosystems. A study from the Nature Conservancy suggests how things like letting trees and grasses grow could have a huge impact. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill has been looking into the study. Hey there, Aynsley.

O’NEILL: Hi, Steve. So, in this report, The Nature Conservancy tried to quantify what improved management and restoration of the land could do to help stabilize the climate.

They looked at how much carbon could be sequestered by such things as leaving grasslands intact and not turning them into agricultural fields. They also looked at the impact of planting trees or restoring wetlands. In fact, there are some twenty-one different natural climate solutions that they investigated. Here’s Joe Fargione, lead author of the study.

FARGIONE: Our study shows natural climate solutions can help fight climate change with a potential benefit that's equivalent to one-fifth of our nation's current net emissions. And that's the same as if every car and truck in the country stopped polluting the climate.

O’NEILL: And Joe Fargione says that if we implement all twenty-one of these approaches, it could set us on the path to meeting our obligations for the Paris Climate Agreement.

FARGIONE: If you look at between now and 2030, if natural climate solutions were ramped up, that could address about 37% of the reduction in climate pollution needed to keep warming well below two degrees, which is, of course, the target that was agreed to at the Paris Agreement.

O’NEILL: One thing we could improve is the US Agriculture Department’s Conservation Reserve Program, where farmers get paid to take marginal land out of crop production, and replant it with native species. Joe Fargione says, since 2007, we’ve lost 13 million acres from that program.

FARGIONE: We estimate that if we put all of that land back into the Conservation Reserve Program, you would get about 9 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent stored per year, the same as taking 2 million cars off the road.

Natural climate solutions have the ability to offer 37% of the carbon mitigation needed through 2030, but only receive 0.8% of public and private climate financing globally. (Photo: Greenfleet Australia, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wow, Aynsley, that’s huge. But how difficult would it be to actually put some of these into practice? It sounds kind of expensive.

O’NEILL: Well, some of these ideas are expensive. But the Nature Conservancy report details some low-cost strategies, like planting cover crops and improving how we manage animal waste. I spoke to Benton Taylor, a postdoc at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. He told me one of the easiest, cheapest, and most effective natural climate solutions is passive – just letting trees reforest themselves, which is practically free!

TAYLOR: When we look at sites that that have been passively versus actively reforested, we don't really see much of a difference in how quickly they get to the sort of old growth forest standard that we're looking for. So, it turns out that nature does a very good job of reforestation on its own. It is much less expensive to passively reforest.

O’NEILL: So, Steve, if we take away the incentives to cut down forests and let them regrow, we could save a lot of effort and money, which we could use to mitigate climate change in other ways.

CURWOOD: And of course, there are lots of benefits to reforestation other than carbon capture.

O’NEILL: Yeah, and Benton Taylor made that point to me as well.

TAYLOR: Reforestation is good for, sort of, counting beans when we're thinking about carbon, but it's also good for a lot of other things biodiversity, soil stability, that sort of thing.

CURWOOD: Alright, thanks, Aynsley, for that report.

O’NEILL: Sure thing, Steve.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- New York Times | “Part of the Answer to Climate Change May Be America’s Trees and Dirt, Scientists Say”

- Click here to read the study in Science Advances

- The Nature Conservancy

- Joe Fargione at The Nature Conservancy

- Benton Taylor’s Website

[MUSIC: David Mallet, “Garden Song” on David Mallet (1978), Neworld Media]

Free the Beaches: Desegregating America’s Shoreline

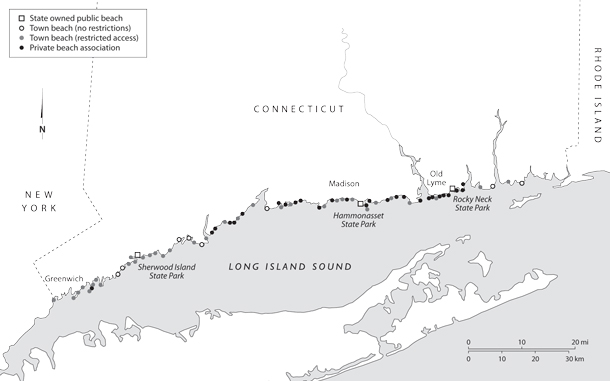

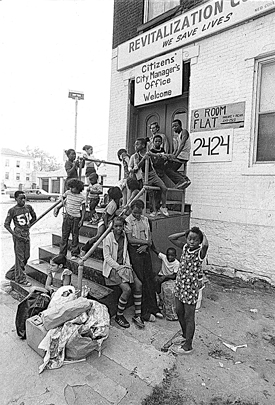

Members of Ned Coll’s Revitalization Corps march for open beaches in the town of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in 1959 a physician in Biloxi Mississippi led a group of black people onto a segregated beach to protest discrimination. The protestors were repulsed by white homeowners and the police, but the “wade in” – as it was dubbed, became part of the civil rights movement not only in the deep South but also in the North. Connecticut and other northern states also had a long history of wealthy white folks barring people of color and the less affluent from their sandy shorelines. So in the 1960s the Connecticut beaches on Long Island Sound became the target of wade-ins, often led by activist Ned Coll. Historian Andrew Kahrl has written a book titled, Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth!

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Please describe for us briefly what the beaches were like along the Connecticut shore in the 60s and 70s, and who got to use them?

KAHRL: Well, they were very limited in their public access. It was a 253-mile shoreline, 72 miles of it was white sand beaches, and of that only seven miles were open to the public. The rest were in the hands of private homeowners, private beach associations, which were sort of like gated communities, as well as clubs and other residential corporations. So, it was, it was a shoreline that has, was effectively off limits to the general public. It was something that really was exclusive to the upper-middle class and wealthy communities that were fortunate enough to live or own summer cottages along the shore.

CURWOOD: So, on to this scene of unequal beach access comes Ned Coll. Who was he and what led him to lead a campaign to free the beaches?

KAHRL: Yeah, so Ned Coll was a young white Irish Catholic, recent college grad, who in 1964, he was working in a comfortable job in the insurance industry in Hartford, Connecticut, and had. You know, was very distraught after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, sensed that spirit of a kind of new frontier of volunteerism of civic engagement was in danger after his death, and quit his job and decided to found an anti-poverty organization called Revitalization Corps. It was – he fashioned it as a domestic Peace Corps that aim to get middle-class, white Americans, primarily those who sort of were living in sort of relative privilege and comfort to become more involved in solving the problems of poverty, of segregation and of racism in America.

Names, locations, and legal status of public beaches along Connecticut’s Gold Coast. (Image: Andrew Kahrl)

He came to the issue of beach access almost by accident. He and the volunteers, many African-American mothers who lived in the communities where he was serving wanted to sort of find ways to get children out of the city during the summer, give them more cultural enrichment activities, whether it be trips to the countryside or other excursions, and they just decided during the summer of 1971 that they would start leading trips down to the shore. They didn't think of it as a protest at all. They thought of it as just another sort of activity that they could do during the summer when kids are out of school. They loaded up a bus of children and mothers and headed down to the state shoreline and discovered that there was very little access available to them. There was few places that they could actually go, and the beaches that they did try to access, they were not welcomed at.

CURWOOD: Hey, remind us how much access that poor black kids growing up in public housing in the 60s and 70s had to places where they could play or cool off on hot summer days there in Connecticut, whether it's Bridgeport or Hartford or whatever.

KAHRL: No, this was a real serious issue. I mean, this was something I talked a lot about in the book is how the summer season really brought a whole host of injustices and deprivations into focus, and it was oftentimes as a result of tragedy. There was a shockingly high number of children in cities like Hartford and Harlem in many cities across the country that would would drown each summer oftentimes playing in unsupervised bodies of water and they were there because there was few other options available. This was something that the Kerner Commission which studied civil disorder in the 1960s and looked to sort of understand the roots of African-American unrest found that, in fact, recreation and the sort of lack of decent and safe places of recreation ranked very high on the list of African-American grievances in some of the cities or racked by violence during these years.

CURWOOD: What did the law say about the public right to access the beaches and where did the idea that beaches belong to everyone come from originally?

KAHRL: Yeah, I mean the idea that the shoreline belonged to the public originated in the Roman Empire. In the year 530 C.E. the Roman emperor Justinian proclaimed that shorelines are common to mankind, that they’re subject to the same law as the sea itself and that no law one can be forbidden from approaching them.

This idea what's later became known as the public trust doctrine has deep deep roots in western law. It formed the basis of the English common law, this notion that beaches were public land and then it became part of American common law with the founding of the Republic. So, this notion that beaches are public property has deep deep roots in American law.

CURWOOD: So, Ned Coll begins really a campaign to free the beaches and he takes this busload of kids and mothers down to the shore and there's not a lot of access. What's the turning point when he decides, hey, I need to make this a cause?

KAHRL: Yeah, really I think you can sort of date it back to that summer of 1971 when they went to the town of Old Lyme, Connecticut, which was one of the many old, upper middle class wealthier communities along the shore, and were greeted very hostilely by the homeowners who felt as if, this was their private beach, this was, they were trying to sort of access what was a private beach association's shoreline. The sort of anger and hostility that greeted him really unnerved him and woke him up to some of the realities of racism in these places that had not really been on their radar. I mean, these are isolated small, sort of little summer enclaves of people of sort of great privilege and it turned his attention to seeking to first engage with these communities and as they became increasingly resistant and hostile to his very presence, seeking to sort of protest and draw attention to this issue.

CURWOOD: There's a passage from your book that describes one of his demos, if you could call that. It's an amphibious invasion of one of these beaches. Could you please read from your book there? I think it's page 187.

KAHRL: Yeah, sure.

On the ride to the shore the kids could barely contain their excitement it would be a Fourth of July to remember. As the Long Island Sound came into view, the vans pulled into the boat landing located next to the private club whose festivities they would soon be crashing. Ned and one of his assistants leapt out of the van and began unfastening the boats from the roof and dropping them into the water. Someone else hung a ladder off the pier.

Once everything was in place, Ned and the volunteers scurried down the ladder and into the boats. The children strapped on their life jackets, climbed aboard the vessels and headed out to sea. On the shore members of the exclusive Madison Beach Club who underwent a rigorous vetting process and paid a $300 annual membership for days like this were trickling out onto the beach and planting themselves underneath one of the club's neatly arranged green umbrellas. Just before noon, three boats appeared, all headed toward the club shore. Ned, with an American flag attached to a pole, leaped off the bow and began marching, MacArthuresque, toward the beach, stopping just before he reached the dry sand he shouted, "Happy Fourth of July everyone," and defiantly planted the flag in the sand.

Children and staff outside Revitalization Corps’s headquarters on Hartford’s North End, c. 1975. (Photo: courtesy of Bob Adelman)

Moments later a plane began circling overhead carrying a banner that read, "Free America's beaches". Club members stared in disbelief. This was an ambush. Parents sqooped their children off the beach and made a hasty retreat to the clubhouse.

CURWOOD: Sounds like those folks were scared.

KAHRL: Yeah, in a sense, it was kind of unlike anything they had ever seen before because the shoreline in many of these towns had been so effective in the limited public access, and not just limiting public access to the beach, but also sort of limiting diversity within their communities. I mean, one of the things that I talk a lot about in the book is the way that many of these towns had and acted exclusionary zoning ordinances that prevented low-income housing or really sort of preventing anyone below a certain income level from being able to live in these towns. So, these were virtually all white and very sort of class homogenous as well. So, the very presence of a busload of children from inner city Hartford was unthinkable for them.

The one thing that I think that really sort of stood out to me especially as someone who had who had previously studied desegregation of shorelines in the South during the civil rights movement at a time where there was horrific violence characterized by efforts to desegregate beaches, you know, wade-ins that took place where mobs of white segregationists would come out into the water with baseball bats and tire irons and violence would sort of erupt. Here in these sort of very well-to-do communities, oftentimes the response was to simply sort of retreat to the clubhouse, remove their children. That was really one of the saddest things is that white and black children would be playing together here on the shore and parents would grab their children and sort of take them away as if that this was some sort of threat to them. At first they sort of reacted with a degree of shock and then anger and hostility as they realized that Ned wasn't coming there seeking permission. They were coming there as asserting their right to access this beach whenever they pleased.

CURWOOD: Now, after a while, of course, there’s litigation, and the advocates for freeing the beaches move ahead, in many cases in court. What stands out as most significant among those cases?

KAHRL: The protests that Ned Coll and others were waging in Connecticut dovetailed with this open beaches movement, which was really national in scope, and from one 1970 to 1980, there were over 150 beach access cases heard in state and local courts. That's up from 10 the previous decade. One of the issues that many of these cases challenged was the right of local communities that had accepted substantial amounts of state and federal tax dollars to help build and enhance their shorelines. Whether they could limit access to residents only when it was really everyone who had helped to pay for these facilities. Now, the interesting thing that happened in Connecticut was the way that very wealthy towns like Greenwich and Madison interpreted these cases was to say, well, the solution for us is to never accept state or federal tax dollars, and they were wealthy enough that they could do that. And so Greenwich in particular developed almost a phobia of any outside funding that was being dangled before them fearing as if it would be some sort of poison chalice that would then lead them into court.

CURWOOD: You write that when some of these communities who were forced to open up their shorelines "to the public" that they found some rather ingenious ways to – and I say that in the diabolical sense of the word –

KAHRL: Mmhmm.

CURWOOD: to nonetheless keep people out. Can you give me some examples?

KAHRL: Yes, so in 2001, the state of Connecticut, the state Supreme Court declared that the restrictions that Greenwich and many others communities were using that explicitly barred nonresidents from accessing their shorelines was unconstitutional. So, at that point legally the beaches were open to everyone, but towns were finding new ways to sort of get around this, and so it could either be through very limited parking access or say having parking lots that only residents could park in. Selling beach passes in a way that was – made it very difficult for non-residents to actually purchase them, but oftentimes, on this issue in particular, there was a real effort to distance ... these communities really stressed that their beach access policies had nothing to do with race. It was simply a matter of private property rights, of the rights of local communities to limit access to residents only, and even went so far oftentimes in a very cynical way to acclaim that they were restricting access out of environmental concerns, that they were fearing that if they letting anyone on to the shores then the shores themselves would be harmed.

CURWOOD: So, basically nature designed the beaches, the coastal areas to be dynamic. That at times the coastline would receded, at other times it would advance. What has all this privatization of beaches done for our ecology do you think, and the lesson we might be able to learn?

KAHRL: Yeah, you're absolutely right. I mean, beaches exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. They're in constant motion. They resist any attempt to sort of stabilize and yet that is sort of the story of coastal America in the 20th century was this constant effort to try to sort of hold beaches in place, whether it be through sea walls, beach nourishment projects. I mean, we spent millions of dollars a year pumping sand onto shorelines in the interest of sort of making them attractive to vacationers or to homeowners and yet much of this is not only sort of is oftentimes quite literally washed out to sea when a storm hits but as well makes the sort of problems that sea level rise poses all the more daunting and pushes us further away from a more sensible and more sustainable relationship with these very fragile stretches of land.

Andrew Kahrl is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Virginia. (Photo: University of Virginia)

And one of the problems that I see ... this was plainly evident after Superstorm Sandy in 2012 was a reluctance to face up to the reality and to heed the call that many coastal scientists have been issuing for years now, which is that we need to begin to retreat from areas that are highly vulnerable to sea level rise and will be uninhabitable, and yet we consistently resist that and instead double down on development and double down on rebuilding. And what drives this? Well, in part it's that ability to be able to sort of colonize the shore and claim beachfront property as your own. This is highly desirable real estate and it's made all the more desirable by the ability of homeowners to be able to not just sort of enjoy the spaces but also to restrict access to others.

CURWOOD: You're an academic, you're not a judge or jury, but how would you rate Ned Coll’s success in his enterprise to try to desegregate Connecticut's beaches?

KAHRL: Well, I think it's undeniable that the activism that he engaged in in the 1970s raised awareness of not just the issue of beach access, but of a larger set of inequalities that were shaping life in the northeast and across the country. For a time Revitalization Corps was really truly national in scope. It spawned hundreds of volunteers, dozens of chapters across the country. People really were drawn to his spirit of civic engagement and sort of local activism, but ultimately it struggled to make long-term gains because of Ned's reluctance to sort of work with others, and to sort of partner with other organizations and to really put in place an infrastructure that would allow communities to organize themselves, and because he was so single-minded in his focus and so adamant in his beliefs, and the issues he cared deeply about that it was oftentimes sort of his way or the highway.

Now that said, the gains that have been made with regard to public beach access are significant. I think that the decision in 2001 by the Connecticut Supreme Court that opened up the state's shoreline to the public could not have been possible were it not for the activism of Ned Coll in the 1970s. But we still see across America this steady trend toward closing off public access and of increased sort of retreat amongst many Americans into private spaces, and that really poses a threat to our democracy as a whole. I mean, as I argue in the book, public space plays a very essential role in a democratic society. These are sort of places where people of different backgrounds, races and ethnicities and income levels can come into contact with each other and really in the process learn how to get along and when we don't have that it leads toward increased polarization, increased division, increased parochialism, and I think the cause that he was championing is an important one that still remains very much with us today.

CURWOOD: Andrew Kahrl teaches history and African-American studies at the University of Virginia. His book is called "Free the Beaches." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAHRL: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Free the Beaches book

- About Andrew Kahrl, Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Virginia

[MUSIC: Summertime (Instrumental) DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince.]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google Play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth