October 18, 2019

Air Date: October 18, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

10,000 Farmers Want a Green New Deal

View the page for this story

A bipartisan coalition of over 10,000 farmers and ranchers from across the United States has signed on to a letter that urges Congress to support a Green New Deal. They’re asking for a massive overhaul of food and farming policy in order to address the climate crisis while providing economic security for independent family farms. Ronnie Cummins is a co-founder of Regeneration International, and an organizer of U.S. Farmers & Ranchers For a Green New Deal, and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (09:39)

BirdNote®: Who Likes Suet?

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

If you’re looking to feed the birds, seeds aren’t the only snacks you can offer. There’s also suet, a type of fat that comes from cows and sheep and is packed with energy. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more about which birds like suet best. (01:48)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering kick off the segment with a call for scientists to receive support in dealing with the grief of ecological loss. They also discuss the mounting pressure to take down four lower Snake River dams which have contributed to the steep decline of salmon populations in the Pacific Northwest. And in the history calendar, they look back to a victory in what some say was the first environmental justice battle. (04:05)

The Economic Value of the National Parks

View the page for this story

The National Parks have been famously called “America’s Best Idea,” but they may also be “America’s Best Investment”, thanks to the valuable services they provide such as recreation, carbon storage, and educational programs. In the new book "Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs," John Loomis and Linda Bilmes attempt to sum up the vast value of the National Parks. Linda Bilmes teaches Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, and joins Host Steve Curwood in the Living on Earth studios. (15:30)

Exploring the Parks: Great Smoky Mountains

View the page for this story

The latest in our series on public lands takes us to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which straddles the mountains of Eastern Tennessee and Western North Carolina. Jeremy Markovich, writer for Our State magazine and host of a podcast called Away Message, shares his segment on finding the most remote spot in the Great Smoky Mountains and chats with Steve Curwood about his time in one of the most biodiverse places in the United States. (11:42)

Arctic Fox Hunting

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender reflects on the resilient attitude Arctic Foxes display in the cold North Pole environment. (03:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Linda Bilmes, Ronnie Cummins, Jeremy Markovich

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Nature is priceless, but we can put a price on the benefits of our national parks.

BILMES: We call them "America's best investment" because Americans treasure the National Parks, both for the recreational spaces that they provide, for the historical places that they curate, for the watersheds and ecosystems they protect, and yet we invest a very very small amount of money in these treasures.

CURWOOD: Also, more than 10,000 farmers and ranchers want a Green New Deal.

CUMMINS: We're talking about a Green New Deal with a strong regenerative focus. And this is the way to bring rural America into an alliance with urban America, farmers and consumers united together, to where we can heal some of this insane polarization that is entirely unnecessary.

DOERING: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

10,000 Farmers Want a Green New Deal

Over 10,000 farmers and ranchers are calling for Green New Deal legislation that prioritizes small, independent farms. (Photo: Ken Hawkins, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

A coalition representing over 10,000 farmers and ranchers from across the United States has signed onto a letter that urges Congress to support a Green New Deal. They’re asking for a massive overhaul of food and farming policy in order to address the climate crisis while providing economic security for independent family farms. Ronnie Cummins is a co-founder of Regeneration International, and an organizer of U.S. Farmers & Ranchers For a Green New Deal. Ronnie, welcome back to Living on Earth!

CUMMINS: Good to be with you.

DOERING: First, your organization is called Regeneration International. And it focuses on the regenerative agriculture movement. So, what do you mean by regenerative agriculture?

CUMMINS: Regenerative agriculture is sort of the next stage of sustainable agriculture. It is a major trend in food and farming because of the climate crisis. Because regenerative agriculture not only avoids the toxic chemicals and the excessive fossil fuel use of industrial agriculture, but it also aims to sequester as much carbon as possible. And so the idea is that if you can reduce in the United States, for example, our fossil fuel burning by, say 50% by 2030, you could literally suck down the remaining 50% equivalent of emissions. And that way you could reach net zero emissions by 2030. That's what the Green New Deal calls for.

DOERING: Wow, I mean, it's an ambitious goal, that's for sure.

CUMMINS: Yes, but we're already, right now in the United States, our forests and our wetlands and our soils, even in their currently degraded state, are sucking down 11% of all the emissions that we send up to the atmosphere. So basically, we're talking about scaling up that sequestration that already exists naturally while we go to renewable energy.

Herbivorous animals such as cows used to be grazed on pastureland before industrial agriculture moved to feeding them grain. (Photo: Aimee Brown, Oregon State University’s Harvey Ranch, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: You know, some people point to deforestation to make room for crops, or the methane releases from the cattle industry. And they say, well, look, farming is one of the biggest problems contributing to climate change. So how could a shift in the way we farm be a part of the solution to the climate crisis?

CUMMINS: Well, before we plowed up the Great Plains and whacked down so many trees, we did have a balance of carbon in the atmosphere and in the soils and the living plants and trees. What happened though, is modern industrial agriculture went too far. And so instead of the Great Plains with deep rooted prairie grasses, what we have now are monocrop corn and soybeans and wheat, and the carbon that used to be in the ground is now in the atmosphere and the ocean. So, it's simply, how do we get it back where it was, you know, 150 years ago. And it's not rocket science. Simply, we have to change the way we manage our farmland and pasture land. We need to have public policy and public awareness and financial investments that will scale up this farmer and rancher innovation that's already out there.

DOERING: You know, I think a lot of us realize that we're consuming in a way, especially when it comes to food, that's just not sustainable. So, what would this actually look like if we had a sustainable animal agriculture system?

CUMMINS: Well, what we say is, right now in the United States, 90 to 95% of all the meat out there, sold retail or served up in restaurants, is coming from factory farms. Intensive confinement operations where -- you know, cows are herbivores, sheep are herbivores. Goats are herbivores, buffalo are herbivores. These animals should not be eating grain. You know, it fattens them up, yes, but it lowers their nutritional profile and it destroys the environment. So, if you look at the land in the United States, about three quarters of all the farmland in the United States is used to graze animals before they go into a factory farm, or to grow the animal feed that they eat in a confined factory farm. This is 10 times as much land as we're using to grow, you know, fruits and vegetables and herbs for our consumption. So, we literally have to change this situation. Stop feeding herbivores grain, get them back out grazing on pasture, which is what they used to all do, and graze them in a way... If you want to sequester carbon, you don't overgraze, but you also don't undergraze, and you're trying to mimic the way animals behaved before we confined them. Typically, under natural conditions, they just eat the top third of the plant, and then they move on. They don't eat the grass all the way to the ground. When the top third of it gets eaten, plants concentrate all their energy rebuilding their flowers and their seeds. This is a survival thing. Well, this is what puts carbon down into the soil. You're not really putting any carbon in the soil if you're growing row crops, corn and soybeans, like most of our prairie that we've plowed up has. So by grazing animals in a way that mimics their natural behavior, you're putting carbon back in the soil. I mean, right now, we're subsidizing factory farms and industrial agriculture. We got to stop paying farmers to do things the wrong way, and start giving them incentives to do things the right way.

DOERING: So, what could Green New Deal legislation do for smaller, independent farms?

CUMMINS: Well, it could make it possible for all the people who would like to get into farming to do so. There's a strong movement in the United States and worldwide of young people who want to get back to the land. You know, the problem, though, it's very difficult to do this if you don't have money. And so we're going to need to incentivize the possibility of young people farming. And you know, minority communities like African Americans, who once were predominantly farmers, Native Americans who were, you know, farmers and herdspeople, they need some subsidies to make up for all the damage that's been done over these years. Latinos are the people who do grow our food and pick our food for the most part, but they certainly don't have enough money to start being farmers. So people are talking not just about the technical changes we need, but about the justice aspects of what we need. There's a lot more people who'd love to farm and they will farm as soon as they're given the opportunity to do so.

Ronnie Cummins is one of the organizers of U.S. Farmers and Ranchers for a Green New Deal. (Photo: Courtesy of Regeneration International)

DOERING: It's interesting that there's all these farmers that have signed on to this letter urging Congress to do some kind of Green New Deal that involves farming because predominantly, the rural communities are more conservative. And, I don't think the Green New Deal can be seen in any stretch of the imagination as a conservative idea at this point. So, what's the political struggle that you have dealt with as you put this coalition together?

CUMMINS: Well, at first, you face that. I mean, Trump got 65% of the rural vote. But a lot of people, they want to see practical results. And so the reason we didn't get the whole National Farmers Union, which has 200,000 members, we haven't gotten them to sign on to this yet; it's because a lot of their members say 'Oh, this is socialism' or 'Oh, this is just the Democratic Party', or 'I like some of the proposals, but let's not talk about Medicare For All and free public education and jobs for everyone, and so on'. And so what we have to try to explain to people is, look, if you want a New Deal for farmers and ranchers, you need the majority of the population to support this. And they're not going to support this unless it's part of a package that, you know, satisfied their primary needs. I mean, Americans don't wake up in the morning thinking about the farm crisis. Everyday people wake up thinking about, oh my God, I can't pay my bills, or I hate my job, or I don't have health insurance, or my kids aren't learning in school, or this is a dangerous neighborhood. So, the brilliance of the Green New Deal, like the New Deal before it, is it's a comprehensive system changing vision. And there's something in there for the overwhelming majority of the population. That's why they're going to support the parts about sustainable and regenerative agriculture, food and farming. You know, they don't want to pay their student loan debt anymore. You know, they don't want to pay the high bills for health care and so on. And the Green New Deal, if food and farming advocates want change, they have to support a holistic package. You know, if environmental justice folks want change, they cannot leave out rural America and still get something through. We're talking about a Green New Deal with a strong regenerative focus. That's what we need. And this is the way to bring rural America, or at least a lot of rural America, into an alliance with urban America, farmers and consumers united together, to where we can heal some of this insane polarization that is entirely unnecessary.

DOERING: Ronnie Cummins is a national coordinator for the US Farmers and Ranchers for a Green New Deal. Ronnie, thank you so much for taking the time.

CUMMINS: Great to be with you today.

Related links:

- Click here to read the group’s letter to Congress

- Consumers for a Green New Deal

- The Regeneration International Website

- HuffPost | “10,000 Farmers and Ranchers Endorse Green New Deal in Letter to Congress”

[MUSIC: Brownie McGhee, “Ain’t No Tellin’” on The Complete Brownie McGhee, by Brownie McGhee, Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Thinking beyond just birdseed to help our feathered friends get through the winter months ahead. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hot Tuna, “Embryonic Journey” on Live at Sweetwater, by Jorma Kaukonen, Eagle Records]

BirdNote®: Who Likes Suet?

Northern Flickers are big fans of suet in the cooler months. (Photo: Courtesy of BirdNote)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: If you’re looking to feed the birds, seeds aren’t the only snacks you

can offer. There’s also suet, a type of fat that comes from cows and sheep and is packed with energy. BirdNote’s Mary McCann tells us more about which birds like suet best.

BirdNote®

Who Likes Suet?

[Tufted Titmouse song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/192213, 0,16-.19]

Fall is a great time to put out a suet feeder. Suet cakes are mostly fat, giving birds a high energy boost to help them survive the cold weather.

Who likes suet? It’s a long and varied list. [White-breasted Nuthatch call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/176168, 0.04-.07]

The chickadee is another fan of suet to help build up their fat reserves to survive the winter. (Photo: Courtesy of BirdNote)

Typical visitors include chickadees and titmice, nuthatches, jays, and woodpeckers.

And keep an eye out for other birds at your suet feeder, especially those whose beaks can’t open seeds. Tiny kinglets, among the smallest of all songbirds, sometimes hover at the feeder. Wrens love a bite of suet, too, as well as almost any kind of sparrow or wintering warbler. [Bewick’s Wren song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/187044, 0.07-.10]

Alas, non-native European Starlings also find suet hard to resist. But there are suet feeders designed to exclude starlings while letting the regular native birds get to the good stuff.

One of those native birds is the Brown Creeper. It’s an especially cool bird to discover at your feeder, because it’s most often glimpsed disappearing briskly up the trunk of a tree.

In the West, mobs of tiny Bushtits sometimes blanket a chunk of suet, taking a break from their normal diet of insects and spiders.

It’s high time to hang up the suet feeder.

I’m Mary McCann.

The Red-breasted Nuthatch likes to frequent suet feeders. (Photo: Mike Hamilton)

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Jay W McGowan, Geoffrey A Keller and Bob McGuire.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org October 2018/2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

https://www.birdnote.org/show/who-likes-suet

CURWOOD: For pictures, fly on over to our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Find out more about this story on the BirdNote website

- Learn more tips about how to feed wintering birds

[MUSIC: Cab Calloway and His Orchestra, “Everybody Eats When They Come To My House,” on Cab Calloway and His Orchestra Selected Favorites, Vol.3, by Jeanne Burns, the Orchard Music/EMI Music Publishing/Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

Beyond the Headlines

The Snake River is a major river of the Pacific Northwest and is the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. (Photo: Flickr, Jerry and Pat Donaho CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. He joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey Peter, how's it going?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Jenni. Gonna talk about an ecological disaster of a different kind. It's one that may be taking its toll on the mental health of scientists who study issues like climate change, extinction, habitat loss, toxic waste, cancer clusters, all the lovely things we cover here on Living on Earth.

DOERING: Oh, yeah. It's really hard not to get depressed doing this kind of work.

DYKSTRA: It is, even though there are also solution stories and at least occasional good news out there. There's a lot of bad news. There's a lot of risk. And because of that, some prominent scientists in the UK published a letter in the journal Science. Not a peer reviewed study, but a letter calling for academic institutions and other places that employ scientists studying the environment that those scientists should be supported, and quote "allowed to cry."

DOERING: Hmm, what kinds of other resources do they suggest giving to scientists?

DYKSTRA: Well, monitoring and a system that might be similar to the grief counselors that are sent into schools or workplaces that have had shootings or perhaps weather disasters. And scientists aren't the only ones, there are environmental activists, there are environmental journalists, in covering these issues every day, have a great potential to get really depressed by what we see.

DOERING: Gosh, well, we need them to keep doing the good work that they do. So, I hope that they do get the help they need. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We'll go to the Pacific Northwest. The Snake River, the Columbia River, spectacular scenery, a lot of commerce and much of that commerce is enabled by huge dams on those rivers and some of the tributaries. They provide hydroelectric power, they allow for navigation, and they control floods. But those dams, as power producers, are beginning to become money losers. So the long push to remove those dams and have the rivers be free flowing is gaining some momentum.

DOERING: It's kind of surprising. I mean, they're so expensive and these dams, don't they provide a good source of low carbon, carbon free energy?

DYKSTRA: They do but they're costly in another way, and that's that they impede the migration of salmon. Salmon, of course, are a anadromous fish. That means they spend their life cycle in both fresh and saltwater. When they swim upstream to spawn, the dams are huge obstacles. There are fish ladders in the river, and other artificial, no pun intended, applications to help the salmon, but the populations have crashed. They're also threatened by disease, potentially by overfishing, and most definitely, by climate change. Add up all of those and removing the dams may be the best hope at saving the salmon.

DOERING: Hmm. So Peter, what's in the history calendar this week?

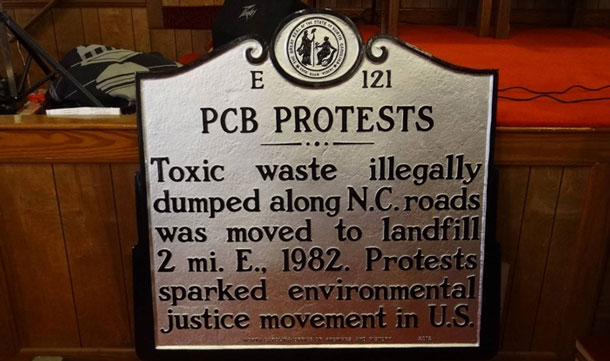

Warren County North Carolina’s protest against illegal PCB dumping is said to be the catalyst for the environmental justice movement within the United States. (Photo: North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program)

DYKSTRA: We're going to turn the calendar back to October 19th, 1982, Warren County, North Carolina. There was a victory in what many people regard as the first big environmental justice battle in this country. Warren County is a generally poor, mostly African American, largely rural county, and the state decided to cite a PCB dump in Warren County. PCBs, of course, are a notorious long lasting carcinogen. And, um, this sparked a huge and unprecedented protest, a month's worth of demonstrations in Warren County, and then the North Carolina capital city of Raleigh. The governor Jim hunt finally yielded to the protest, canceled the project. But here we are four decades later, and environmental justice issues still pop up on an almost everyday basis.

DOERING: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Peter, we'll talk to you next week!

DYKSTRA: All right, Jenni. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories at our website Loe.org.

Related links:

- The Independent | “‘They should be allowed to cry’: Ecological disaster taking toll on scientists’ mental health”

- Inside Climate News | “Global Warming Is Pushing Pacific Salmon to the Brink, Federal Scientists Warn”

- Timeline | “The EPA chose this county for a toxic dump because its residents were ‘few, black, and poor’”

[MUSIC: Tim & Molly O’Brien, “If I Had My Way” on Remember Me, by Rev. Gary Davis, Sugar Hill Records]

The Economic Value of the National Parks

Funding for the National Park service has remained flat for decades despite a steady rise in visitors from 200 million in 1980 to 330 million in 2018. (Photo: Grand Canyon National Park, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The National Parks have been famously called “America’s Best Idea,” but they may also be “America’s Best Investment”, thanks to the valuable services they provide such as recreation, carbon storage, and educational programs just to name a few. In the new book "Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs," John Loomis and Linda Bilmes attempt to sum up the vast value of the National Parks. Linda Bilmes teaches Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, and she joins me now in the Living on Earth studios. Linda, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BILMES: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So what makes the national parks and programs "America's best investment"?

BILMES: We call them America's best investment because Americans treasure the national parks both for the recreational spaces they provide, for the historical places they, that they curate, for the watersheds and ecosystems they protect. And yet we invest a very, very small amount of money in these treasures. So when we looked at them carefully, and we tried to understand, well, what is the value of protecting the national parks, we found that the value is at least 100 billion dollars, which is a 30 times multiple of what the federal government actually spends on the national parks each year.

CURWOOD: So the National Park Service gets about three billion dollars, two or three billion dollars a year?

BILMES: Well, the national parks are funded through a very complex formula, but overall, over the last 20 years, their funding has been flat at the same time that the number of visitors in the parks has increased by about 50%. So they get about, from the federal government, they get about two and a half to three billion dollars a year. And they get some money from private philanthropy and they get some money from concessionaires. But overall, they're operating on a shoestring.

CURWOOD: For something that's worth 100 billion dollars, you say.

BILMES: Well, for something that on a very conservative basis is worth 100 billion dollars. And what we did in the book, and in the study over the past 10 years is we tried to put a price on something that is, in many ways, priceless. But we tried to use standard economic techniques to figure out, if we did try to understand and estimate the value of protecting these places, what would the American people actually say? What would they be willing to pay in additional taxes to not lose these treasures? And we found that at a very conservative level, that figure was 100 billion dollars, at least.

The National Park system protects unique features like Corona Arch in Arches National Park, Utah. (Photo: Tom Gainor, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: So throughout your book, there are these constant reminders that the national park system and the associated programs contribute to society in ways that we just don't really realize. Remind us of those underappreciated contributions that we get from the parks.

BILMES: Well, we went through in our book a number of ways that the national parks create value. And some of them are, are things you, you could think of, like ecosystem services, for example; they sequester carbon, they are, some of the national parks are carbon sinks. They also protect watersheds, they protect wildlife, they generate a lot of tourism dollars. And they also, however, do a few other things that don't immediately come to mind. So one of the interesting chapters in our book, is where we talk about the importance of the national parks in the US movie and TV industries. There have been thousands of blockbuster films that have been filmed in the national parks -- thousands.

CURWOOD: Your favorites?

BILMES: Well, I mean, I have to admit, I am a Star Wars fan.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

BILMES: And the Star Wars Tatooine was filmed in Death Valley. And we interviewed some people who had been involved with Lucasfilm, and they talked about how they chose it, and how it was a place that really looked like it was another planet.

And they also didn't have to worry when they were filming there about having a McDonald's arch in the background, because it was protected. But I also am a fan of the, the redwoods, where ET was filmed, and Forrest Gump, which was filmed on the National Mall, which is a park. So I think that the sort of iconic films have a value, and what we tried to do is to look at and break down that value. So there are values like the fact that the national parks protect certain iconic places. So for example, in the Planet of the Apes when they come back and they see the Statue of Liberty, you don't have to say anymore. It's an icon. Now, that's protected by the National Park. So we try to just introduce the fact that this is one of the most successful industries in the United States. And actually, the National Parks plays a role, even though they don't derive any money from this service.

Parks including the treasured Yellowstone National Park have been shuttered during multiple government shutdowns in recent years. (Photo: National Parks Conservation Association, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: I understand there's a maintenance backlog in the National Park Service of, what, 12 billion dollars? And you point out in your book that the current funding mechanisms just aren't sustainable. So you propose strategies like setting up a national parks endowment. Why would that help ensure that the National Park Service can carry out its, its mission in the generations to come?

BILMES: Well, the National Parks has a very interesting mission. The mission is to protect these special places in perpetuity, in pristine condition, for the enjoyment and recreation of the public. So it's a dual mission, both to protect these places in perpetuity, and to protect them so that people can go visit them and have recreational opportunities in them. And that means you can't just protect them by kind of shutting people out; the whole purpose is to protect them for people's enjoyment. So there's a fundamental disconnect, a misalignment, between the goal of the parks, which is this perpetuity kind of goal and mission, and the way that we fund the parks, which is on a very annual basis where we fund just the operational salaries. And what we have been falling behind on is investing all these long term assets. So maintaining the roads, maintaining the trails, maintaining the parking lots, maintaining the visitor centers, investing in the forests, investing in making sure that firefighting prevention is up to date -- all of these things just keep falling further behind because we've just been sort of funding the, the minimum of the operational needs year to year.

CURWOOD: And there's nothing like a government shutdown to make funding even crazier. Now, let's break down some of the suggestions you have to make the funding of the parks consistent. First of all, an endowment. What would that be? How do you envision an endowment working?

The National Park Service’s Junior Ranger program provides kids with the opportunity to learn more about the national parks. (Photo: daveynin, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BILMES: When I served on the Second Century Commission, I served with a number of luminaries, including Sandra Day O'Connor and civil war historian, Pulitzer Prize winner James McPherson, and many others. And we spend a year thinking about the fact that we are now celebrating the centennial of the National Parks and thinking, isn't it great that 100 years ago, we had this great idea, which has now been adopted throughout the world of protecting these places. And we tried to think, 100 years from now, what can we do today that we will look back on and think, Oy, we are so glad that 100 years ago we had that idea. And one of the things that we thought about was the funding structure, that if we could figure out a way to make the funding sustainable for the next century, that would be a great thing to do. So we looked at what is the way that organizations with a long term mission create sustainable funding? So organizations like universities have endowments. Many organizations like museums, and hospitals have endowments, and these are a mechanism for enabling an institution to prepare for and fund the long term.

CURWOOD: So Linda, institutions, I'm thinking of the Smithsonian, which is supported in part by federal funding, don't charge for admission. But I think with the exception of the Great Smokies National Park, just about all the big national parks charge a pretty hefty fee per vehicle -- what, 30, 35 dollars? Why do we charge at the gate, how necessary is that, and what does that do for access for people that maybe don't have that much disposable income?

Star Wars, A New Hope, filming in Death Valley. Many iconic movies and TV series have been filmed in U.S. National Parks, at a very low production cost. (Photo: NPS)

BILMES: I think that the question of access to the parks is a really important question. And there are different ways that one could think about it. When you think about the Smithsonian, the Smithsonian Institution is funded partly through a trust, and partly through the federal government. So they have a mixture.

CURWOOD: So that trust is your endowment that you're talking about?

BILMES: Well, it's structured a little bit differently, but I mean, they do have the ability to fund things outside of the federal government funding. Now, the National Park fees overall, there's been a lot of effort to keep them low, to keep entrance fees low. But the fact is that the national parks are in pretty difficult shape right now, in terms of their financial circumstances. You have a situation where, since 1980, we've gone from 200 million visits a year, to 330 million visits last year. At the same time, their budget has remained flat, and the number of requirements and mandates that the national park staff has to do just to keep up has gone up. For example, the amount of fire prevention efforts that they have to do, and the amount of trail maintenance, has increased. But in order to make ends meet, the national parks have cut the number of staff members by 7%. And I think that the public kind of understands that, but all of these numbers are pretty hard to put in perspective. So when I think about the national park budget, and I think about the overall budget, I think, well, the national parks are this incredibly beloved part of the government. People love the parks. And when we were doing our study, when we were first doing this survey, we did focus groups around the country, and I heard people from all over the country talking about how they had emigrated to the US from wherever they had come from -- that they might themselves not be that interested in nature or parks or whatever. But they were so happy that their children had this opportunity to go to the seashore, to go and learn about historical places, to go and to hear this American story in these special places, that they, this was one of the best things about their new country. And yet we are not funding them. And it's not just a matter of giving them a few more dollars every year. It's a matter of aligning the structure of the funding, giving more flexibility to private benefactors and donors and to the national parks themselves, to be able to create a funding structure that is able to keep these places going for the next hundred years.

CURWOOD: You write about perhaps having a multi-year budget cycle for the National Park System. I think a lot of agencies would love to be in a multi-year cycle and not have to put up with the annoying wrestling on Capitol Hill; why should the National Park Service have such an arrangement, do you think?

Some National Parks feature excellent night sky viewing. (Photo: David Morris on Unsplash)

BILMES: Well, I believe that there are many agencies in government that should be on a two year cycle rather than a one year cycle. I was very supportive of the Department of Veterans Affairs going to a two year cycle, because they shouldn't be disrupted when they're administering hospitals around the country in the middle of the cycle because Congress can't pass a budget. But the fact that the national parks are so beloved, has made them kind of fair game to be a potato in these government shutdown games. So every time there's a government shutdown, the National Parks has to shut down. And every time there's almost a government shutdown, the National Parks has to prepare to shut down. So you have these places which are all over the country, they take a lot of management because they have visitors, they have facilities, they have all this operational stuff that goes on, and they keep having to either prepare to shut down or shut down, and then they shut down, they have to reopen, they have to reopen the facilities.

CURWOOD: I'm thinking of the most recent set of shut downs, we saw Joshua trees literally getting cut in the Joshua Tree National Park.

BILMES: Well, I think people are extremely indignant because the national parks belong to everybody. And so people from all different walks of life are deciding that they're going to take a vacation, and they're going to go and see the Joshua Tree or they're going to go and see the giant redwood trees that have been around for hundreds of years. Or they're going to go and see those trees at Gettysburg which have got cannonballs embedded in them, that were alive during the Battle of Gettysburg. They're going to go and see this. This is for many people a once in a lifetime trip where they're going to take their children, they've organized themselves to do this. And then because the government can't pass a budget, completely unrelated to anything about the parks, the parks become this political hot potato, this political football, that get shut down. I think it's ridiculous, in general, but I think that one quick fix would be to give the parks a multi-year appropriation.

CURWOOD: In your work you, of course, work closely with a number of economists and scientists and researchers, but you also run into ordinary people when you're out there. Tell me a story of when you were out in one of these national parks, you met somebody and it really, it really inspired you to keep up with this work, which obviously isn't particularly easy.

From left, Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood with Professor Linda Bilmes. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

BILMES: I will tell you a story that almost broke my heart. Some years ago when I was serving on the National Parks Advisory Board, we were in the Santa Monica National Recreation Area. And we participated in a trip that the local Los Angeles School District was partnering with the Park Service, with the rangers, in bringing kids to the beach. And these were fifth graders who lived maybe half an hour from the beach. And we got to the beach, and so many of them had never seen the sea. Ever. They were in the fifth grade. And they were kicking off their shoes, and running into the waves. And they were so happy and excited and just joyful with the sea. And it was just incredible because many of them had never been there. And they come from families that have, are working three jobs. They don't have time to bring their kids to the seashore. Or maybe that's not something that they're confident about. And it was just wonderful to see this partnership between the national parks and the schools, bringing these fourth and fifth graders to the sea.

CURWOOD: Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs was edited by Linda Bilmes and John Loomis. Thank you so much for taking time with us today. Thank you.

Related links:

- Valuing U.S. National Parks and Programs: America’s Best Investment

- Learn more about the National Park Service and “Find Your Park”

- About Linda Bilmes

[MUSIC: Peter Ostroushko, “Mallard Island Hymn” on The National Parks – America’s Best Idea (Soundtrack) by Peter Ostroushko, The National Parks Film Project/PBS]

DOERING: Coming up – We’ll continue our ongoing National Parks series and take a trip off the beaten path, literally, through the most visited national park in the United States.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, “Brazilia” on The Classic Quartet-Complete Impulse! Studio Recordings, by John Coltrane, The Verve Music Group]

Exploring the Parks: Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains. (Photo: Andrew Kornylak, Our State Magazine)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, “This Land is Your Land” on Naturally, Daptone Recording Co]]

[SOUND OF BULL ELK CALL]

That’s a bull elk bugling along the Catalochee Creek in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, one of sixty-eight native mammals in what’s considered the most biologically diverse national park in the system. And there are some 200 native birds, including the barred owl with its ghostly call.

[CALL OF BARRED OWL]

CURWOOD: It’s home to 30 species of salamanders, and 14 different frogs and toads, including the bull frog.

[SOUND OF BULL FROG]

But its vast biological diversity doesn’t end there. There are more than 1500 varieties of flowering plants, over a hundred trees and dozens of native fish and reptiles.

In all, science has documented over 19,000 species in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and last November scientists and the park celebrated the discovery of the one thousandth unique species to be found nowhere else except the Great Smokies. It was a lichen.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is huge, with more than a half million acres that straddle the mountains of Eastern Tennessee and Western North Carolina. And it has the highest point along the Appalachian Trail, Clingman’s Dome, which is higher than New Hampshire’s Mount Washington. It’s the most popular national park, with more than 11 million visitors each year, nearly twice that of the second most visited, the Grand Canyon. It is also the only major national park that is free. The roads in the park make it accessible, and that’s how most of the millions of visitors enjoy it. But it has a huge backcountry, home to some fifteen hundred bears, and that is where reporter Jeremy Markovich of the North Carolina Magazine, Our State went looking for the most remote spot in his state, defined as the furthest point from a road.

MARKOVICH: This story begins where the road ends.

MAN: Well, now there’s an echo.

The backcountry of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. (Photo: Andrew Kornylak, Our State Magazine)

MARKOVICH: This is the end of what’s called the “Road to Nowhere.” It’s a road through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park that was never finished, and ends on the other side of a tunnel a few miles west of Bryson City.

The trails on the other side will get us very close to the most remote place in North Carolina. In all, it’s a 21-mile hike that’ll take us two days.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

The most remote spot in North Carolina is deep in the backcountry of the Great Smoky Mountains State Park – five and a half miles away from a road. That’s where I find myself hiking with my friend, the photographer Andrew Kornylak, and a local guy we found in Bryson City named Dwayne Parton. A man who had thru-hiked the entire length of the Appalachian Trail, and got the trail name “Jellybean”.

PARTON: Jellybean, yep.

MARKOVICH: Because one time he’d shared his jellybeans with another hiker.

PARTON: And I let him take out of the jar.

MARKOVICH: And that hiker gave him the norovirus.

PARTON: Well, I got the norovirus the next day. [LAUGHS]

MARKOVICH: The first day of hiking was easy. The weather was great. We crossed beautiful mountain streams, saw butterflies and snakes. When we got to the campsite, we sat down and talked with Dwayne, who said he enjoys the outdoors, but came to it very late in life.

PARTON: I needed a reset.

MARKOVICH: Why did you need a reset?

PARTON: Well the truth [is], I went through a really nasty divorce. Everything that you knew about yourself is gone. It’s like you wake up and then someone that you love tells you, ‘Hey I don’t love you.’ Oh my gosh, what just happened? You’re floored. And that’s the start.

MARKOVICH: Three years ago, Dwayne hiked the Appalachian Trail — and he finished on his 30th birthday. Since then, he’s bounced around a bit, to Alaska, Oregon, Montana and then back to North Carolina.

MARKOVICH [TO PARTON]: What did you learn about yourself after doing all that?

PARTON: I don’t know if it’s like anything specific, you just feel more confident in who you are. Like, if singing is your example, maybe my voice is just never meant to sound like someone who can sing really well, and just coming to grips with that. Like, that’s just who I am, and that’s okay. Like, having peace with just being who you are instead of trying to be someone that you’re not is a pretty big part of being alone.

[SOUNDS OF RAIN ON TENT]

MARKOVICH: So it’s almost 9:00 on day two, and that sound is the rain that’s hitting my tent.

So, here’s a fun fact: The Smokies are the wettest part of North Carolina. And so, we set out to find the most remote spot in the state in a downpour.

[HIKING SOUNDS]

MARKOVICH: First, we hiked up to the top of a ridge. Then, at 4,900 feet in elevation, we followed a new trail along the ridgeline for a mile until…

PARTON: If start making our way down the hill there, I think we’ll hit it.

MARKOVICH:… we had to leave the trail behind. And this is why we’d brought Dwayne with us, because he had experience going off-trail. And going off trail is not something you take lightly. Right away, we were surrounded by green in every direction. Dwayne was wearing a green shirt — not the best choice.

MARKOVICH [TO PARTON]: Where’d you go?

MARKOVICH: Plus, it was slippery and I fell.

[MUFFLED SOUNDS]

MARKOVICH: But soon, thanks to the GPS on my phone –

This is it.

-- we found the most remote spot in North Carolina.

KORNYLAK: Who in their right mind would go out here? [LAUGHS] Nobody!

MARKOVICH: It was anti-climactic.

MARKOVICH [TO KORNYLAK]: What do you think about, about this?

KORNYLAK: It’d be cooler if we saw a bear. That would make it cool.

North Carolina’s most remote spot. (Photo: Andrew Kornylak, Our State Magazine)

MARKOVICH: We’d planned on staying here longer — to listen, to look around and to feel what we could feel. But we were wet and tired. And after 15 minutes, we set back out to find the trail. After a long, long hike back, we made it back to our cars -- just before nightfall.

That night, Dwayne, Andrew and I had pizza and beer in Bryson City. By then, the rain had let up and you could see these wispy white clouds hanging among the green mountains. And I remembered what Dwayne had said the day before, about his reason for coming with us.

PARTON: I had kind of forgotten what it was like to be on the trail. So, you come out and set up camp and you’re walking around in the woods and there’s no internet to distract you. It’s kind of like ‘Oh wow, this is kind of nice. Yeah, this feels good. I forgot how good this feels.’

MARKOVICH: Remote isn’t always a place. Sometimes, it’s a state of mind.

CURWOOD: Jeremy Markovich is a reporter for the North Carolina magazine Our State. He's also host of the podcast Away Message. And he joins me now. Thanks, Jeremy. That's a really nice story.

MARKOVICH: Oh, thank you.

CURWOOD: So, what's it look like right now here in the fall, towards the end of October, in the Great Smokies?

MARKOVICH: You know, it's great no matter when you're up there, but this time of year is especially vibrant. And this is the time when the Smokies really get packed with leaf peepers. And it's just... all the colors are amazing. And everywhere you look it's just this amazing palette of color and just... it's great. It's something that you have to take in, I mean, pictures sometimes don't even do it justice. It's just in every direction.

CURWOOD: And you can see these colors in the back country, where you were, finding this most remote place, but right on the roads.

MARKOVICH: Oh yeah, like right off the road. Heading through the park, the color is just everywhere. And this is the interesting thing. I mean, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most visited park in the national park system, but there are different parts of it. So, the parts off the roads are usually packed with people and in the parts that I went to, which is kind of the western edge of the park, there's not as many people. In fact, the place where we left for the hike, you know, we saw a few people in maybe the first mile, and then that was about it. So, the Smokies are usually very busy, but not busy everywhere.

CURWOOD: Right, so, with the folks who maybe don't want to hike, there's beautiful stuff to see and maybe a few more people, but in the back country, you can be by yourself. And the lesson of your story, apparently, is that you have to go away to find oneself. How fair is it to say that?

MARKOVICH: You know, sometimes it's a little bit presumptuous to think that we can go out and find ourselves in a weekend, over a couple of days, over one long hike. I think, when I set out, I just wanted to see what it was like, but I kind of thought it would shake something loose. And it did, but not in the way that I thought. I mean, I thought I would go to this most remote place and feel something that I didn't actually feel. And what I ended up coming out of it was... you know, it really is a state of mind. You really have to think about yourself and what it means to isolate maybe your mind as opposed to isolating your physical presence. So, it took me a trip way out in the Smokies to figure that out. But that is something that I figured out.

CURWOOD: Uh-huh. And what was the benefit?

Jeremy Markovich, writer for Our State magazine and host of a podcast called Away Message. (Photo: Courtesy of Our State)

MARKOVICH: You know, I think it's a matter of sending yourself to somewhere that you don't know what's going to happen. I think sometimes it's very easy, in an age where you can Google anything, you can bring anything up at your fingertips right away, the information is there. I mean, if you want to learn about anything on Earth, it's not hard to at least get a few sentences on it. And when I stood out there, you know, I knew a little bit about what it was going to be like out there. I didn't know exactly what it was gonna be like until I got there. I really didn't have any clue as to what this spot would be like. And when you get there, it's a spot in the woods. It's a little bit underwhelming. But it's something that you do feel a little bit of discovery. You feel like 'I've done something that very few people have.' And so I think it is setting a goal and then trying to achieve that goal and then you get a lot out of it that you didn't even think you were going to get out of it.

CURWOOD: Even if you fall on your tail feathers.

MARKOVICH: Even if you do that.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, how valuable is the Great Smokies National Park? If I understand this correctly, this is the largest wild space east of the Rockies. It's one of the very few places where you can actually get to a wild space, with everything from bears and elk and many, many stinging mosquitoes.

MARKOVICH: Yeah, it's kind of this green oasis in the mountains. And there are a lot of wild spaces all across that area, but it's as accessible and as useful as you want it to be. I think that's the part, is that you can explore in the Smokies for a very long time and see so many different things. I mean, one of the things about being out there was, one of the nights we camped, I was in my tent and everything kind of lit up as if there was a car out there. As if there were, you know, headlights coming across the tent flap. And I walked out and I was, 'Well, what is this?' And it's the fireflies. And the fireflies were so bright, and the light was just incredible. And, you know, you have to be in the right place at the right time or go out there to experience it for yourself to see those sorts of things. You know, another group of people that we actually met out there, they go out there every year, and they've been doing that for maybe a week at a time every year, for years and years and years, these two guys. And they barely ever see anybody, maybe they’ve seen like a dozen people during that entire time out there. So, they keep on exploring this one huge place. And it allows you to come back and back and back and just see different aspects of the same place. Every time you go out there, it surprises you.

CURWOOD: Isn't it amazing that the fireflies actually blink in synchronicity? That they do it all as a group?

MARKOVICH: Yeah. It's incredible. I mean, I knew that that was a thing. And then I got out there and it happened and I was just like, 'Wait, what?' It like erases your mind because it's just... happens in a way that you do not expect. And so you have to see, oh, this is the thing that you expected and you're still blown away by it.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about an amazing creature or plant that you've seen there.

MARKOVICH: You know, that's the thing. It is so vibrant. It's like it was painted by Disney illustrator. It is lush and green in every direction. You are really in a temperate rainforest, and that's not like an exaggeration. You know, some parts get up to like eight feet of precipitation every year. And so it just causes everything to grow and grow green. And then you can run into a bear out there. You can run into all kinds of stuff out there. Whatever direction you look in, you're going to see some aspect of nature and it goes on in all directions, as far as you can see.

CURWOOD: Amazing. Jeremy Markovich is a reporter for the North Carolina magazine, Our State, and also hosts the podcast Away Message. Jeremy, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

MARKOVICH: Thank you.

Related links:

- Away Message Podcast

- Our State | “The Getaway”

- Our State Magazine

- More from Jeremy Markovich

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Woodsong Wanderlust”]

Arctic Fox Hunting

An Arctic fox lies down on a patch of snow. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: Winter is on its way in the far north, a time when animals must use all their senses to get by in the vast white landscape. And as Living on Earth’s Explorer in residence Mark Seth Lender reports, the Arctic Fox is well equipped for the stark environment.

Arctic Fox Hunting

Churchill Point, Manitoba

© 2019 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

Cold slams shut like a safe door, the snow locked down like an iron box. Along the ridge, and through the icebound scrub, where the Arctic willow holds

back its buds comes the Arctic Fox, into the clearing. He stops. He cocks his head --

2 Left, 3 Right, 5 Left -- listening for the tumblers to click. And pounces! Face buried in the powdery stuff. And comes up empty. Arctic vole won’t let go of her stronghold house made fast by snow and silence.

An Arctic fox prancing through the snow. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Arctic Fox changes tack, working instead by the sharp of a nose that follows the track his eyes cannot see, the sound his ears cannot hear. Inhaling... Exhaling... The odors he detects are both storyline and cartography. Of what went this way and that. And what hides. He prods and tests, trying to pick an unpickable lock; to beat Winter’s Time Clock. And Time, is running, out. Head down, body slinking low, fox climbs onto the blue ice rising between boulders… suddenly trapped by a scent, too sweet to pass. His attention in its gentle grasp he rolls, onto his shoulders and stretches his limbs, toes outspread, ears pulled back, lips teased to a foxy grin.

What does the unseen world say to Arctic Fox? What is his pleasure? What perfumes speak from the rime crusted cold? Sea sweet innards of seal drizzled down the chin of polar bear? The place where ptarmigan found [YAWNS] sleep? Did a pair of Arctic hare have congress here in anticipation of a distant Spring? Did snowy owl dine on some delicious morsel, right here? He knows, of Wonders you and I will never uncover.

Arctic fox. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Arctic Fox stands and arches his back in what might seem a domesticated gesture reminiscent of the lapping dog, who will never be his equal in the perpetual Quest, never contribute his fluffy manicured pallor to the white on white; only Arctic Fox invests with meaning.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender. To see pictures, check out our website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s Website

- Special Thanks to Frontiers North

[MUSIC: Bill Evans, “Waltz for Debby” on Live in NYC, OJC]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks to Frontiers North. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth