November 8, 2019

Air Date: November 8, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Big Keystone Oil Spill

View the page for this story

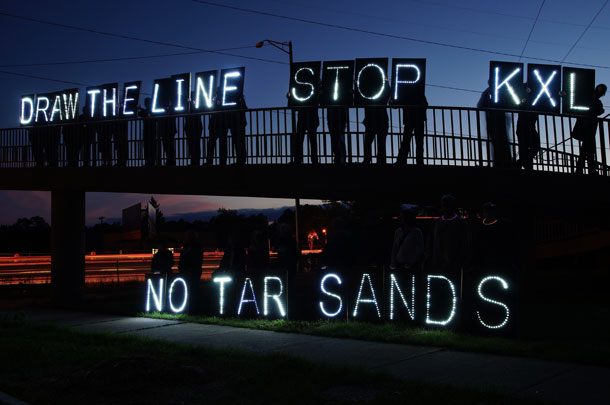

On Oct 29 a nearly 400,000-gallon oil spill was discovered in the Keystone pipeline system in North Dakota, inundating a wetland with heavy crude oil mined from the Alberta tar sands. A controversial proposed extension of the Keystone pipeline system to the Gulf Coast known as Keystone XL has been the focus of ongoing protests and court battles, and the report of the spill came on the same day operator TC Energy was assuring regulators at a hearing it has properly considered environmental and safety impacts of the proposed extension. Sierra Club Senior Attorney Doug Hayes and Host Steve Curwood discuss the impact of the spill and the ongoing legal battle over Keystone XL. (08:13)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

In light of the murder of Indigenous climate activist Paolo Paulino Guajajara in Brazil, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood consider the correlation between violence towards environmental activists and authoritarian regimes. They also turn to a dramatic increase in New Delhi air pollution and the measures that the city is employing to fight back, including the distribution of 5 million face masks to school kids. Peter Dykstra wraps up on a more uplifting note by celebrating the Washington Nationals’ World Series Victory with the tale of EPA whistleblower Hugh Kaufman and his alter ego: The Chicken Man. (04:02)

Wildfires Strike Baja California

View the page for this story

The extreme heat and winds that fueled wildfires in the State of California this October also fed fires in Mexico’s Baja California. KPBS reporter Max Rivlin-Nadler reports on the recovery efforts already underway, and tells Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about how limited resources made fighting these fires especially difficult. (08:54)

BirdNote®: The Butcherbird

View the page for this story

Wander through the open tundra and green taiga forests of northern North America in summer and you might hear the sweet and herky-jerky call of the Northern Shrike. But as BirdNote’s Ashley Ahearn warns: don’t be fooled, this singer has a dark side. It’s a ferocious hunter, a demon butcher of tweet street that impales its prey on thorns or even barbed wire, then slowly tears it apart. That’s why the shrike is also known by another name, the “butcherbird.” (01:36)

Let The Leaves Be And Feed The Birds

View the page for this story

Autumn brings fallen leaves in temperate zones, and the chore of raking all those leaves into piles. But it turns out that a lazy fall yard-work ethic can help native birds. Tod Winston of the New York Audubon Society explains to Host Steve Curwood why leaving fallen leaves and dead flowers helps insects that are food for birds. (07:42)

Rainforests ‘Worth More Alive Than Dead’

View the page for this story

Earth’s rainforests are astonishingly biodiverse ecosystems that can even drive the climates on faraway continents. But they’re disappearing in the name of the kind of economic development that values rainforests more when logged, mined, or turned into farmland. Tony Juniper, author of the book Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth’s Most Vital Frontlines, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the amazing science of how rainforests work and why leaving them intact offers more, not less, economic benefit. (14:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Doug Hayes, Tony Juniper, Max Rivlin-Nadler, Tod Winston

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra, Max Rivlin-Nadler

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Nearly 400,000 gallons of oil recently spilled from the existing part of the Keystone pipeline into a North Dakota wetland, raising questions about its extension.

HAYES: There are several endangered species along the pipeline route. Birds like the whooping crane, interior least tern, piping plover. So, an oil spill anywhere along the pipeline route would have significant impacts to species.

CURWOOD: Also, why Leaving those fallen leaves on the ground and dead flowers standing helps feed the birds.

WINSTON: In a flower garden, leave the flower heads of beautiful flowers like sunflowers, black-eyed susans, coneflowers - those seed heads provide millions of seeds that last through the winter and provide a smorgasbord for birds to feast on all winter long.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Big Keystone Oil Spill

Protests against the Keystone XL Pipeline have been ongoing since its proposal by TC Energy in 2009. (Photo: Courtesy of the Sierra Club, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The proposed Keystone XL pipeline link would bring tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada through North Dakota all the way to the gulf coast in Texas. The project has been in and out of the courts for years and continues to be a controversial point of protest, especially for Native Americans in the region. In response to a federal court order State Department officials recently held a public hearing about the project’s safety and environmental impact. That very same day nearly 400,000 gallons of oil spilled from a leak in an existing portion of the pipeline into a wetland in North Dakota. For more I’m joined now by Doug Hayes, a Senior Attorney at the Sierra Club. Doug, welcome to Living on Earth!

HAYES: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: These spills seem to keep happening. Talk to me, please about the history of Trans Canada Energy's pipelines when it comes to oil spills.

HAYES: Sure, well, the Keystone One pipeline was approved in 2008 and came online in 2010. At the time, they billed it as state of the art technology, one of the safest pipelines ever built. And it spilled thirty-five times in its first year of operation alone. So that was fourteen times in the United States and twenty-one times in Canada. And then in the last few years, we've seen at least four significant spills. So this pipeline spill in North Dakota was almost 400,000 gallons. In 2017, there was another spill of around 400,000 gallons in South Dakota. Also there were big spills in 2011 in 2016. A lot of these seem to have been caused by problems created during construction. So TC Energy seems to have some serious problems with their Keystone system.

CURWOOD: Doug, how does it strike you that at the same time that Trans Canada energy is trying to move the Keystone project forward, and in fact, they are at a public hearing in Billings, Montana that same day, you get this rather large spill, what does it tell you about the company?

HAYES: It certainly causes some concern and casts doubt on their assurances that this pipeline will be operated safely. The larger problem is that these pipelines cross, and Keystone XL in particular, would cross over 1000 waterways. One of the main concerns on the Keystone XL pipeline is the crossing of the Missouri River, which is just outside the Fort Peck Assiniboine Sioux Reservation in Montana. The pipeline would cross under the Missouri River just upstream from their water supply system. And that's just one of many places where a spill would cause catastrophic damage. Also, the pipeline would cross the Ogallala Aquifer and other important water resources in Nebraska, and other places along the pipeline route.

The spill in Walsh County, North Dakota. (Photo: Taylor DeVries, North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality)

CURWOOD: Well surely there are more concerns than just drinking water. I mean, in a wetland, there are a number of creatures from amphibians, birds, all kinds of creatures that rely on drinkable water themselves.

HAYES: That's right. And the federal judge in Montana last year ruled that the State Department had not adequately analyzed the risk of oil spills to endangered species. So there are several endangered species on the pipeline route. Birds like the whooping crane, interior least turn, the piping plover, and in the Missouri River, there's the pallid sturgeon endangered pallid sturgeon. So you're right, the oil spill and any of these not just into the waterways, but anywhere along the pipeline route would have significant impacts to species that live along the route.

CURWOOD: What are the complicating factors in cleaning up these types of spills?

HAYES: The oil pipelines that carry tar sands crude oil pose unique risks because the tar sands oil is what's known as diluted bitumen. It behaves differently when released into waterways. So, if you think about a conventional crude oil spill onto waterways, a lot of it will float on the top and there's a certain spill response mechanisms that they can use, such as skimmers and booms and other things that would contain the spill. With tar sands crude oil or diluted bitumen it's much heavier and it separates, a lot of the properties fall to the bottom of the water column. So, a lot of those traditional cleanup technologies are ineffective for tar sands crude. So they're only just realizing, you know, some of these unique risks and coming up with ways to respond to tar sands spills. But so far the conventional cleanup technologies have proven ineffective.

CURWOOD: Now talk to me about the legal battles going on around the Keystone pipeline system. I gather that there's a lawsuit that your organization, the Sierra Club and other groups, including, what, the NRDC and the Center for Biological Diversity, the Bold Alliance, perhaps and others have against the US Army Corps. What is that suit all about, and what's its status?

Diluted bitumen from Canadian tar sands is a heavy form of crude oil that can sink to the bottom of lakes and streams, contaminating waterways. (Photo: Joe Brusky, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HAYES: You're right, we have a coalition of environmental groups, including the ones that you just named have a lawsuit challenging the US Army Corps approval of the pipeline in federal court in Montana. And the lawsuit challenges the Army Corps streamlined approval process for the majority of the water crossings along the Keystone XL route. So as I said the pipeline will cross about 1200 different waterways. There are outstanding permits that the Army Corps still has to grant for the Missouri River crossing in Montana and that's the subject of the ongoing environmental review. So that approval has not happened yet. But the Army Corps has already approved the vast majority of the pipelines’ water crossings in the four states without doing any meaningful environmental review, without allowing the public to be involved without evaluating oil spills at all. It's a streamlined process that the Corps uses called Nationwide Permit 12. It's sort of a blanket approval, and that's what the lawsuit is challenging.

CURWOOD: So what's the status of the construction of completing Keystone XL right now?

HAYES: So TC Energy has not started construction of the Keystone XL pipeline. The injunction imposed by the Federal Court in Montana prevented them from starting any construction in 2019. They began to do some preconstruction work, which includes building the worker camps, stocking pipes in pipe yards and so forth but they did not complete all of that work in 2019. And just last month announced that they would not do any further preconstruction. So no single mile of Keystone XL pipeline has been constructed yet.

CURWOOD: To what extent does the future of efforts to complete the Keystone XL pipeline project depend on who occupies the White House a little more than a year from now?

Doug Hayes is a Senior Attorney with the Sierra Club. (Photo: Courtesy of the Sierra Club)

HAYES: Well, that's a good question. I mean, the State Department since 1968, has had a permitting process over cross border pipelines like Keystone XL. Last year Trump threw that out the window and said from now on, you know, the President will sign the permits himself or herself. And I think because he essentially scrapped the process altogether and made a unilateral decision, I think that you know, really opens the door to the potential for an incoming president to reverse that decision. If TC energy were to start construction of the pipeline next year, I think that it would not yet be operational by the time that January 2021 comes along and a new president comes into office.

CURWOOD: Doug Hayes is a senior attorney with the Sierra Club. Doug, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HAYES: Sure, happy to be here.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Keystone Pipeline Leaks 383,000 Gallons of Oil in Second Big Spill in Two Years”

- SFGate | “South Dakota Keystone XL Opponents Point to North Dakota Spill”

[MUSIC: The Wayfaring Strangers, “Cluck Old Hen” on This Train, Rounder Records, a division of Concord Music Group]

Beyond the Headlines

Illegal loggers have threatened the Guajajara Indigenous group as well as their forests. (Picture: crustmania, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta. Hi there, Peter. How you doing?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. I want to start with something that we touch on, it seems at least once a year. It's not a fun topic, but it's something we have to discuss. There's been another environmental activist, murdered, this time in Brazil.

CURWOOD: This story just comes up too many times. Who is it this time Peter?

DYKSTRA: Paolo Paulino Guajajara is 26 years old. He's an indigenous leader trying to protect a pristine area along the northeastern coast of Brazil. He was ambushed by loggers. Another one of his group Guardians of the Forest was wounded. Paolo was shot through the head and killed.

CURWOOD: Boy, I have to say that it's tough for environmental activists everywhere but it seems like Latin America is especially risky.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, what we always hear is that Honduras is the most dangerous place for environmental activists with a huge death toll and intimidation in the air. We've talked quite a bit about Berta Cáceres, the anti-dam activist who was murdered in 2016.

CURWOOD: Yeah, just after she had won the Goldman environmental prize.

DYKSTRA: Right, and there tends to be common ground between harassment and violence toward environmental activists and authoritarian regimes.

CURWOOD: Okay, here you go. What else do you have for us this week?

In 2019, New Delhi’s air pollution has been ranked among the worst in the world. (Photo: Sumitmpsd, Wikimedia Commons, CC-SA BY 4.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, it seems India and China are always involved in a gruesome annual competition to see whose cities have the worst air pollution problems.

CURWOOD: Alright, so who gets the dystopian prize this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, last week, New Delhi distributed 5 million facemasks to school kids. The streets there in a normal time of year are choked with the air from dirty cars and from dirty factories. But this time of year crop burning in the areas around New Delhi makes things even worse. Pollution levels there last week were more than seven times what's considered to be hazardous.

CURWOOD: Oh boy, that's pretty tough. I hope you have something more uplifting for us from the history vaults this week.

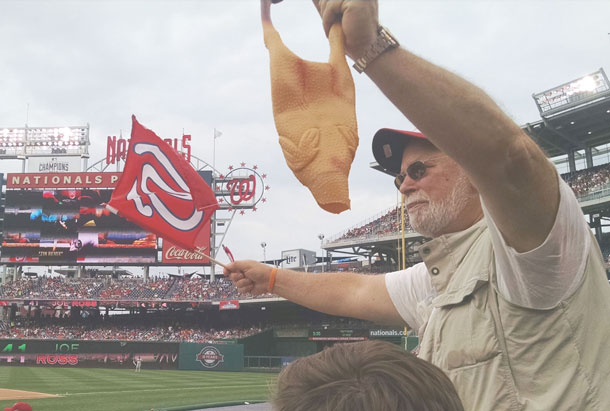

DYKSTRA: Yeah, actually we do. We should congratulate the Washington Nationals for winning the World Series. The last time a Washington team won the World Series was in 1924. But there's a connection between the national pastime and the things we normally talk about here in this show.

CURWOOD: And that would be?

DYKSTRA: A gentleman named Hugh Kaufman. 76-year-old career EPA employee, started punching a clock at EPA headquarters a few months after the agency was founded in the early 70's. And he's a lifelong Washington baseball fan.

CURWOOD: And I know that name Hugh Kaufman and that would be because?

DYKSTRA: Back in 1983, Hugh became the toast of Washington whistleblowers when he released documents that led to the scandalous downfall of EPA boss Anne Gorsuch and sent her top deputy Rita Lavelle to the slammer for perjury.

CURWOOD: Oh yes, part of the Ronald Reagan administration's efforts to dismantle environmental regulation. And of course Anne Gorsuch's son is now Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch.

EPA whistleblower Hugh Kaufman waves his signature rubber chicken to ensure good fortune for his team, the Washington Nationals. (Photo: Edwin S. Grosvenor, Wikimedia Commons, CC-SA BY 4.0)

DYKSTRA: And Hugh Kaufman continues his work at EPA by day but also by night and during ball games. He's sort of a mascot for the Washington Nationals. Known as the chicken man, he sits behind the Nationals dugout and waves a rubber chicken to cheer on the Nats and to try and rattle the opposing team which seemed to have worked in the series.

CURWOOD: Indeed I think it must have. Hey, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website including a picture of the rubber chicken at loe.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | The political context of Guajajara’s murder and his indigenous forest guard Guardians of the Forest

- Read more on New Delhi’s car rationing system

- Interview with Hugh Kaufman and his rubber chicken at a Washington Nationals game

[MUSIC: Madeleine Peyroux, “Reckless Blues” on Dreamland, by Bessie Smith & Jack Gee, Atlantic Recording Corporation]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The wildfires in the state of California don’t just stop at the border with Mexico. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Wayfaring Strangers, “Cluck Old Hen” on This Train, Rounder Records, a division of Concord Music Group]

Wildfires Strike Baja California

The wildfires carried by the Santa Ana Winds destroyed several homes in Colonia Morelos Rosarito. (Photo: Max Rivlin-Nadler)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

California has been especially hard hit by wildfires this year, on both sides of the border with Mexico. The recent spate of fires in the State of California burned thousands of acres of land and left millions without power. And south of the border in Baja California, fast moving fires recently had firefighters struggling to get control. At least 3 people died in the outbreak. KPBS reporter Max Rivlin-Nadler has the story.

RIVLIN-NADLER: Aracely Brown is the mayor of Rosarito once a resort beach town that has in the past 20 years exploded into a city of over 70,000 people. We're driving up to Colonia Morelos, a neighborhood that's perched on a hill overlooking the city. On Friday night, Brown had raced to the neighborhood to help residents escape a fast moving wildfire that had swept through a nearby valley, fueled by Santa Ana winds.

BROWN: No, never before in the history of Baja California have there been fires like this. Never.

RIVLIN-NADLER: Brown says the fires destroyed more than 60 houses in Rosarito and at least three people died. Brown says that following strong rains over the winter, there was far more vegetation in the valleys that was able to burn.

BROWN: [La lumber brincaba] The fire leapt in. Other times the fire ran no more, but this time the fire jumped and it fell on the roof of the houses and burned down the houses quickly.

RIVLIN-NADLER: The communities hardest hit by the fires last weekend were the ones highest up in the hills where the residents were least eager to leave their properties. Many residents don't have official paperwork to show that their homes belonged to them and were worried that if they left they wouldn't be allowed to return. Up in Morelos, the city has set up a station where people whose houses have burned down can register for assistance, get a medical checkup and get replacement documents like birth certificates that might have been destroyed in the fire. Brown's administration is handing out large tents for people to stay in on their properties while they rebuild. Eusebia Supulveda-Vega lived in her home with seven other family members. She's lived there for 17 years. Their entire house burned down.

SUPULVEDA-VEGA: There have been fires, but they never came here.

RIVLIN-NADLER: Her family only had a few minutes to escape the flames. They didn't have time to take anything with them, so all of their possessions were destroyed. But they aren't wasting any time rebuilding their home. Volunteers have offered food, their labor, and even an oven as they try to recreate what they've lost. Eusebia says she knows that with more winds in the forecast and extremely dry conditions, that they're still at risk. She says they only plan to rebuild just this once.

Volunteers have started rebuilding buildings affected by the fires. (Photo: Max Rivlin-Nadler)

SUPULVEDA-VEGA: No, no, nothing more. Only one time.

RIVLIN-NADLER: Seasonal fires have long been a part of the ecosystem in Baja California. This isn't the first time that the area around Morelos has burned. In fact, before the neighborhood was called Morelos, it was known as “los quemados” or “the burned”. The previous settlement there was destroyed by a wildfire decades ago. Omar Ortiz is the head of the firefighters in Rosarito. It was up to his small department of under one hundred firefighters, both full time and volunteer, to put out rapidly advancing flames in Morelos, which has no running water.

ORTIZ: The topography is very complicated. The mountains are very steep. It's very difficult for the equipment to get there. It's tough to bring the water up from below and then it gets muddy and it's even harder to get the trucks pass.

RIVLIN-NADLER: Ortiz says the risk of fire has only increased as people have moved up into the mountains trying to find cheaper places to live in the prospering city.

ORTIZ: Situations like this will become more common and we're going to need more firefighters, more trucks, more hoses, more firefighters in this area.

RIVLIN-NADLER: The rebuilding of Morelos has begun. Local businesses have donated their workers and resources and students have begun clearing out toxic ash from hollowed out houses with cities expanding their footprints further into areas that have a long history of seasonal burning. The question for these neighborhoods is not if the next fire will hit, but when, and if they'll be ready or able to get out of the danger in time.

CURWOOD: For more details about the fires in Baja, KPBS reporter Max Rivlin-Nadler spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran, who grew up in Rosarito.

BELTRAN: Could you please describe the scene in Rosarito?

RIVLIN-NADLER: So Rosarito is a town in between Tijuana, which is this massive metropolis, and Ensenada, which is a much more established city. Rosarito has been growing for the past two decades, it's doubled in size. And as it's doubled in size, what's happened is people have moved away from the city center and up more into the hills, into places that weren't really seeing a lot of development before. It was a lot of, you know, it was forest, it was coastal forest, and then it became farming. And now it's becoming residential, you'll see these huge residential complexes stretching off into the horizon, where before there was nothing. So that's really fueling the growth, is kind of this internal growth. And then of course, you have the "gringos", you've got the Americans coming down. This is something, you know, we see playing out in California as well, where if you have an affordability crisis, people tend to move to where things are cheaper, a little bit more off the grid. And unfortunately in California, that means you're running a much higher fire risk. And that's what we've seen in Baja over the past two weeks, just as California has had to deal with really, really dry conditions and very strong winds, the same has been happening in Rosarito and Baja in general and that led to a series of fires.

BELTRAN: Yeah, I grew up in Baja California, and I remember the Santa Ana winds. They are definitely strong in Rosarito. But I have honestly never seen fires this big. Why are they so out of control this year?

RIVLIN-NADLER: One of the reasons why they're much bigger this year is because of a very wet winter for this area. There was a lot of fuel to burn and a lot of wind to help that burn and keep moving. But also, because Baja just hadn't burned in a really long time. There haven't been large forest fires. So you're seeing a lot of things that have been built up over a series of years get ready to ignite. On top of that, you do have kind of smaller fire departments that are less equipped to deal with multiple fires at once. They are stretched very thin for places that are growing very quickly and that don't have as large of a tax base as California does, just through people not paying taxes or much more informal styles of housing. So you have these fire departments that have maybe less than 100 people in the case of Rosarito, that's including volunteers, who are fighting very active fires that are fast moving and that are tough. And on top of that, a lot of these areas do not have running water to begin with. So one thing that we require in California, for example, is you have to have some, some access to potable water. A lot of these communities that were in harm's way in Baja did not have access to running water and had not been set up to the grid. So any water that was needed to fight these fires had to be trucked up.

Max Rivlin-Nadler is an investigative reporter for KPBS News in San Diego. (Photo: Courtesy of Max Rivlin-Nadler)

BELTRAN: I know California residents are accustomed to fires breaking out each year, but this definitely came out as a surprise to people in Rosarito. How are Rosaritenses dealing with this, for instance, in evacuation and the unprecedented loss of their homes?

RIVLIN-NADLER: Right. So one thing that we found and, you know, mentioned in the story is that people are really wary of leaving their homes, especially in kind of these more informal neighborhoods where people don't necessarily have legal documentation that says this home is theirs. You know, they've been living here for 20 years, it's intergenerational; nobody with them present would challenge that. That being said, much like California, Baja California is experiencing an incredible land rush where real estate prices are skyrocketing, foreign investment is way up. A lot of people are interested in getting into Baja land ownership. So a lot of these people are really, really wary of leaving high risk areas just because their families lived there forever. So even in the case of where a family had their home entirely burned down, they weren't going to leave and that's where the government kind of met them halfway and said okay, if you're not going to leave, we're not going to make you leave. One thing we are going to do is we're going to give you a very large, you know, eight person tent and you could live in that house, the remains of the house, until you can rebuild. And the rebuilding started almost immediately. You know, in the US, we have a system where people look for insurance payments, these things take years, whereas in Mexico, there is no insurance for these homes. A lot of the people living there have not paid taxes which would qualify them for some semblance of insurance in the Mexican system. So what you end up with is people wary of vacating their homes, setting up their own campsites, literally where their homes used to be and then reconstructing them, essentially on the ash of their old home.

CURWOOD: That’s KPBS reporter Max Rivlin Nadler speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- KPBS | “Wildfires Scorch a Growing Rosarito in Baja California”

- Al Jazeera | “The ‘Crisis’ Driving Some Americans to Move to Mexico”

- The Atlantic | “California Is Becoming Unlivable”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: The Butcherbird

Northern Shrike posing in Nome, Alaska, on the coast of the Seward Peninsula. (Photo: Mick Thompson, CC)

CURWOOD: Halloween may be over but as Ashley Ahearn of Bird Note reports, some birds do have a spooky way to catch their dinner.

BirdNote®

The Butcherbird

[Song of Northern Shrike]

AHEARN: The Northern Shrike is a robin-sized, pale gray bird with black wings and a jet-black mask. But don’t let this quirky, metallic song fool you. It’s the call of a bloodthirsty killer.

[More song]

The Northern Shrike breeds in the tundra and taiga of the north, but migrates south for the winter, perching on the tops of tall trees and shrubs to look for prey.

A juvenile Northern Shrike begs for food. (Photo: © Robert Mortensen)

The shrike is a meat-eater, diving down from its tall perches to catch insects, small mammals, and even other birds. It’s such a fierce hunter, it’ll often take down prey bigger than itself. Then it carries its meal over to a thorny bush, or maybe to a barbed wire fence, and impales it, sticking its meat on a hook, before slowly tearing it apart — the way we might eat a rotisserie chicken.

That’s why shrikes are also known by another name, the “butcherbirds.”

If you want to see a Northern Shrike in action, head to open country in Canada and the northern U.S. And listen for the “butcherbird’s” innocent-sounding song.

I’m Ashley Ahearn.

[Song of the Northern Shrike]

###

Adapted from a script by Frances Wood

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Narrator: Ashley Ahearn

Song of the Northern Shrike recorded by Kevin J. Colver. Used with permission. Eastern Washington ambient recorded by C. Peterson.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2019 BirdNote November 2019

ID# 110905NSHR NSHR-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/butcherbird

CURWOOD: For pictures fly over to the Living on Earth web site, loe.org

Related links:

- This Butcherbird story on the BirdNote® website

- Click here to learn more about identifying the Northern Shrike in the wild

- Audubon Society | Shrikes Have an Absolutely Brutal Way of Killing Large Prey

- Learn more about the latest Shrike research

[MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley “Autumn Leaves” on the Jazz Playlist, Pt. 11, River Records]

Let The Leaves Be And Feed The Birds

Many birds, like the Black-Capped Chickadee, rummage through the leaf litter in fall and winter in search of the seeds and bugs that may be hiding underneath. (Photo: Tom Murray; Flickr CC)

CURWOOD: A lazy fall yard-work ethic can actually be big help for native birds. And the Audubon Society has tips on how to use leaf litter to create helpful spaces for birds in your own back yard. Tod Winston is a Birding Guide and Research Assistant for the New York City Audubon Society, and joins me now. Welcome to living on earth.

WINSTON: Thank you so much, happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why would keeping a messy fall yard be a benefit for birds?

WINSTON: Well, you know, in so many areas where people live, an aesthetic has taken over, over the past decades that is something like a pristine English estate, you know of lawn, and house, and not much more, a few ornamental shrubs. And that habitat is something that people feel comfortable with. But it's really not a habitat that's made for birds and wildlife. And something approximating more of a wild habitat can provide a much richer habitat for the wildlife and birds that so many of us love.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, though, I mean, this is such a wonderful thing to do in the fall, you get the family together, you all get out there raking and you do pruning and everything looks all neat and tidy afterwards. And it's a whole ritual.

WINSTON: So, I'm remembering lovely times, raking the leaves, I guess that you remember the good parts of it, it wasn't all lovely. But I remember raking the leaves with my father and grandfather, that was something we all did in the fall, it was something that was expected of us. But I guess what I would recommend though, is leave a space that is a happy place for birds and wildlife to spend the winter and you know, that's something that will reap benefits throughout the entire year, not just the wintertime.

CURWOOD: So Todd, what can you do to keep up what you call a messy yard?

It may be customary to rake leaves in the fall, but taking a break from the yard work may help the wildlife in your backyard by providing them food and shelter. (Photo: Jessica Quinn; Flickr CC)

WINSTON: So, you know, there are a number of things to think about, and one is certainly to leave the leaves on your property or rearrange them at least, so that they can provide a nice leafy rich understory for critters to overwinter in. Another is to, in a flower garden, leave the flower heads of beautiful flowers like sunflowers, black-eyed susans, cone flowers, those seed heads provided millions of seeds that last through the winter, and provide a smorgasbord for birds to feast on all winter long. Another way to provide a great habitat for birds is to create a brush pile of fallen branches or pruned branches. And you can do that by building a brush pile with larger branches underneath and smaller branches above; that creates an amazing shelter for all sorts of critters, including birds. And related to those dead branches is to leave dead branches where they fall and leave, if you can, snags or dead trees standing, which are great habitat for woodpeckers. Woodpeckers will excavate holes that, then, all sorts of birds like chickadees, and titmice, nuthatches will also nest in. So you know many of us in our desire to clean up our woods remove dead trees and those dead trees are really important for birds.

CURWOOD: Of course under leaves, one finds worms, right?

WINSTON: Right. So there are all sorts of critters that live under leaves, and some are good for birds, worms, and particularly moth pupae, you know, you see moths and butterflies and you don't often think about, a lot of us, I think, that all moths and butterflies are in cocoons, like a monarch butterfly on a plant. But actually, the vast majority of moth pupae are in the ground. Those moths, that caterpillars that are munching on leaves when they're ready to metamorphose they dropped to the ground. And so on a property without a rich ground habitat of leaves, those moths have nowhere to create their pupae and create a new generation of moths. And, come springtime many birds, forest birds depend on all the critters that live in the leaf litter - beetles, moth pupae, worms. As well, many creatures that are beneficial to the garden - praying mantises, lace wings, ladybugs, they all over winter in that leaf litter. So if you - you're actually doing your garden a service by leaving that leaf letter and providing habitat for critters that are beneficial to the garden.

CURWOOD: Tod, you must have some tips for folks who are really avid bird fans.

WINSTON: You know, a lot of folks who first get into birding are shocked when they just start to listen and open their eyes to see what lands in their, as birders say, patch. And that means just see what shows up where you live. An important thing to think about look to see what's growing there. You may have native plants that are really important for birds that are right there and you don't have to buy them, all you have to do is give them a chance to thrive in your yard.

CURWOOD: So, what specific varieties of plants do you recommend to encourage visitation from our feathered friends where I am, we have actually an invasive species an autumn olive that well the bird seem to like that.

WINSTON: Well, you know, like people like potato chips and Cheetos, birds like shrubs like the autumn olive. Autumn olive berries are kind of tasty, I kind of like them myself, but that really is part of the problem with non-native shrubs that have been planted and have escaped and spread all over the United States. Plants like autumn olive, multiflora rose, bitter sweet, Japanese honeysuckle, the list goes on and on. Those are plants, all of which have tasty berries that birds like, and birds eat those berries and then spread the seeds all over the place. But when it comes to the spring time, and birds need bugs to feed their babies, those non native plants don't have, host a rich insect life and do not provide the protein that, via insects, that birds need to feed their babies. That's really the problem. So when we're thinking about what to plant in our yards we should be thinking about what birds need all year round. There are many kinds of shrubs, service berry, and trees, black cherry, that are native to where we live, at least here in the in the northeast. And there are varieties and of those plants across the United States that can be great for birds.

Tod Winston is a Research Associate with the NYC Audubon Society. (Photo: NYC Audubon Society)

CURWOOD: Tod, you live in New York City. Where do you live, a place where you have control over your yard?

WINSTON: I live in an apartment on the third floor of a little apartment building. But you know, even people who live in urban settings can put some native plants on their balcony or on their patio. And those plants could be useful both to breeding birds and to migratory birds that pass through the city.

CURWOOD: By the way, talk to me about the history of yard work. Why do people rake up the leaves in their yards to begin with?

WINSTON: You know, I honestly don't understand that, people are obsessed with being neat and tidy. You know. And that is a basic part of it, that people are afraid of the disorder, afraid of what's lurking in those leaves. And, you know, part of this effort to get people to connect to the nature in their backyards, to have positive impact for the nature in their backyards, is to connect them to what lives in that leaf litter. They're all sorts of fascinating creatures and beautiful creatures that depend on messiness, that depend on native plants. And, you know, just like new birdwatchers, people who are new to really observing what's in their gardens can be amazed by the variety of life that live there.

CURWOOD: Tod Winston, birding guide and research assistant for New York City's Audubon. Tod, thanks for taking the time with us today.

WINSTON: Thank you so much for having me on. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about local birds in your neck of the woods

- Find out which plants are native to your neighborhood

[MUSIC: Cannonball Adderley “Autumn Leaves” on the Jazz Playlist, Pt. 11, River Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The global importance of rainforests and a roadmap for saving them. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jerry Leake, “In a Sentimental Mood” on Vibrance -- Jazz Vibes and World Percussion, by Duke Ellington, Rhombus Publishing]

Rainforests ‘Worth More Alive Than Dead’

Through a mechanism called the biotic pump, rainforests are able to generate rain that falls back on them and can even influence faraway climates. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

From the Congo to the Amazon to Borneo, rainforests are home to countless species we haven’t even discovered yet. But these treasures of biodiversity are rapidly disappearing. Western market forces place a higher value on soy, oil palm, or cattle that are grown on deforested land than on the intact rainforest itself. In Brazil, for instance, slash-and-burn efforts to clear the Amazon have led to an increase in deforestation in 2019 of about 85%, compared to 2018. All is not yet lost, but we’re running out of time, writes author Tony Juniper. Tony’s new book, Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth’s Most Vital Frontlines relates the astonishing science of how Earth’s rainforests are connected with climates and landscapes all the way around our blue green marble and uses conservation success stories as a roadmap for saving what’s left. He joins me now from Cambridge, in the UK. Tony, welcome back to Living on Earth!

JUNIPER: Very nice to see you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: What's famous about the Amazon rainforest to many people is that it is incredibly diverse. A temperate forest might have maybe half a dozen or a dozen tree species, you write in your book. But of course, a tropical rainforest is gonna have, what, 500 or more in a single hectare! Why are rainforests so incredibly diverse, what makes them so?

Tropical rainforests require flowering plans to invest in blooms and nectar to attract animals to move their pollen. Passion Flower (Passiflora vitifolia), Costa Rica. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: This is a really good question, one that's been pored over by ecologists for decades. My answer would be it comes down to the long term stability of these systems and the extent to which they don't really have seasons. So in a temperate forest, you find we go through spring, summer, autumn, winter, and the system is being interrupted. But in the tropical forest, you have this continuity of circumstances running through the entire year, year after year. And this causes the ecology to become very diverse with lots of threads of interconnections being created, that otherwise wouldn't necessarily be sustained if you had these seasonal annual interruptions. And you can look at all these threads of connections and they become very, very specialized in tropical forests with, for example, a single insect being the sole pollinator of a particular kind of plant, a particular tree; its fruit is being moved by a particular partner bird or mammal. And those things, they become very tightly woven. And the other thing is the extent to which these conditions create opportunities for diseases as in pests to become very rapacious. And so the trees and other organisms have adapted strategies to be able to cope with attacks by pests by dispersing themselves through the forest and making sure that any one species is living at quite low density. So, it's the combination of these kinds of factors, which I think come down in the end to this very high level of productivity coupled with stability, that leads to these incredible webs of life to emerge over long periods of time.

CURWOOD: Tony, there's really interesting part of your book, Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth's Most Vital Frontlines, where you describe how the rainforests like the Amazon can drive their own weather. Talk to us about how this biotic pump works, please.

An astonishing diversity of insects, birds, and bats help pollinate the flowers of rainforest plants. Geoffroy’s tailless bat (Anoura geoffroyi), Costa Rica. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: So you imagine the forest there, and rainforests, obviously, they have a lot of water falling upon them. Less appreciated is the amount of water coming out. And so across the Amazon each day, some 20 billion tons of water are being evaporated into the atmosphere. And when that water vapor is coming from the leaves on the trees, it's in the form of a gas, vapor. But when that vapor, what goes up into the air on the warm rising air currents that are being driven by the sunshine, the water vapor gets up to high altitude, and when it gets to high altitude, it condenses, it turns back into tiny water droplets because of the cooler conditions. And at that point, the vapor going from gas to liquid, it collapses in on itself, it occupies a smaller space of atmosphere. And this then creates a vacuum, which then causes this colossal, powerful updraft to come from beneath. So the condensation is really a pump that's driving the air currents skywards, and then you get these towering great storm clouds over the forest. And they're obviously creating vast amounts of rainfall, but they're also driving atmospheric circulation at a much bigger scale, with the Hadley cells, which drive the circulation of the Earth's atmosphere in the middle latitudes being driven by this updraft reaching a certain altitude, then going horizontally towards the subtropics. And as the forest is pumping air skywards, it's drawing in air from the side, you could imagine this circulation where air is coming off of the sea. And as it's being pulled off of the sea by this vacuum that's pushing the moisture up into the sky, it's bringing in moisture off of the Atlantic and then that's being pulled right across thousands of miles of the rainforest towards the great wall of the Andes Mountains. And this great system is only now really just beginning to be appreciated. But it has huge implications for the entire world because those moist forests that run around the equator, some of them at least, are pushing out water that's traveling thousands of miles. And indeed, during the course of my research, I spoke to American researchers who were finding connections between the forests of Central America and the Amazon, and indeed the grain fields of the Great Plains of North America, in the Dakotas and in Manitoba into Canada, water even traveling that far, which has its origins over the tropical rainforests.

Giant trees like this one hold a high proportion of the above ground carbon trapped in the living fabric of the forest. Masoala National Park, Madagascar. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

CURWOOD: You write about how dust serves as a natural fertilizer and gets to the Amazon rainforest on the wind. How does that work?

JUNIPER: One of the things about the tropical rainforests is how they are living on a nutrient knife-edge, that the nutrients are being consumed in a voracious way because of the way the plant growth is, is so rapid and so lush. And some of those nutrients are being lost along rivers as a result of the decay of plant material. And some of that is being washed into waterways and being removed. And in those areas of tropical rain forests that are on very ancient rocks, the nutrients were used up tens of thousands of years ago. And so in order for the forest to continue to function, nutrients need to come in from elsewhere. And one connection that I write about is the input of nutrients coming from the North African Sahara Desert, and how that driest part of the world is helping the ecosystem in one of the wettest parts of the world to function. And there's a place in the Sahara called the Bodélé Depression, where great dust storms occur quite regularly. And this is kicking up material into the atmosphere that's traveling at high altitude and you can see this on satellite photographs showing this dust plume going away across the Atlantic, with some of this material falling out over the Amazon, bringing with it, for example, phosphorus, an essential plant nutrient, which is helping the system to keep going. And it's another example of these global interconnections. One is water, one is carbon, and another is nutrients. And I think you know, the more we understand about all of these things, the more we can see the interconnectedness of how this entire system is working.

Dust from the Sahara Desert provides vital nutrients for the Amazon rainforest. (Photo: Wolfgang Hasselmann, Unsplash, public domain)

CURWOOD: Just recently, the United States and Brazil agreed to promote private sector development in the Amazon and in fact, Brazil's foreign minister said that opening the rainforest to economic development was, in his view, the only way to protect it. And they pledged 100 million dollars to a biodiversity conservation fund. How helpful do you think this is, or not?

Some ecologists hypothesize that the lack of seasons and long periods of stability in rainforests have contributed to elaborate evolutionary adaptations like the camouflage on this lichen katydid (Markia hystrix) in Costa Rica. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: It will depend upon the details and what kind of development the strategists of that kind of program have in mind. But what I would point out is how the rainforests are already very important for economic development for the people who've lived there for thousands of years, namely, the indigenous people. And it's really a question of what kind of economy we think can coexist with those ecosystems, because the indigenous people have been there, literally for thousands of years, and they've been sustaining their societies, their civilizations, through an economic system that regards the forest as worth more alive than dead. The Western kind of economic model tends to see the forest as most valuable when it's been converted into timber, or when the minerals have been extracted from underneath, or when the forest has been cleared away to make way for agriculture. And so economic development can mean many things to many different interest groups, and it certainly can be compatible with the long term conservation of the forest. But if the decision makers who are putting together these proposals think that economic development that involves the removal of the forest and its replacement with fields, farms, hydroelectric dams, and mines is sustainable, then I would beg to differ. I don't think that is sustainable. And in the case of the Amazon, we're approaching the point where we know that we do run the risk of reaching tipping points whereby we will have cleared so much forest, that even that which is left will no longer function properly, because the system has been degraded beyond the state that keeps it going. And this is particularly the case in relation to rainfall. And the extent to which that will remain a wet forest, after a certain level of clearance and fragmentation that causes that finely-poised hydrological system to break down in ways that cause it to turn into a savanna, or even into a grassland. And when it's in those states, that territory, it will provide a different set of values to the world than those which it's providing now. And those values that we're getting at the moment are important for the entire planet, from the point of view of economic development, literally. And so we know climate change is a global problem. And the carbon that's held in those forests at the moment is benefiting the entire world economy. If we start to degrade that function in order to get short term economic growth of the Western kind, then I do think that would be a mistake.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that Indonesia has made attempts to curb deforestation and the associated fires there. And in June of 2019, the Environment Minister pledge to make a moratorium on new forest clearing for palm plantations or logging operations, make that permanent. How effective has that moratorium been so far?

Tony Juniper is the author of Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth’s Most Vital Frontlines and eight other books. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: It's to be warmly welcomed that we see this kind of policy being laid out by the Indonesian government. But as is the case everywhere it's the difference between the ambition and the practical implementation, which is really the key test. And in Indonesia, a very complex situation exists on the ground whereby government policy isn't necessarily translated into the kinds of things that we would hope to see. And there is a high level of illegal activity in that country in terms of land that should be protected inside national parks and other conservation areas being encroached by palm oil plantations or illegal logging operations. One would hope that the Indonesian government can be working with others to be able to not only set out the ambition of policy and to back that with good science, but to have the means to be able to implement that on the ground. And this is, you know, it's not only about the question of illegal versus legal activities, of course, this is about social development with very large numbers of people living in remote rural areas who often have little opportunity other than to be growing crops for either their own consumption or for market, and being able to work with them to enable and to support sustainable practices so that they can make a living without destroying the forest.

CURWOOD: There have been successes in protecting rainforests around the planet. And you write with some enthusiasm about what's happened in East Africa and Tanzania, in the mountains there, the Amani forest. Describe that for us, would you please.

Fungi are among the myriad of species that assist in the rapid recycling of nutrients in rainforests. Cup fungi, Choco rainforest, Colombia. (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: So there's this fragment of upland forest in the Tanzanian Highlands, an area of incredible biological richness, lots of species unique in the world there. And, you know, the forest has been highly fragmented and much of it gone. And there's one area that was considered doomed by scientists back in the 1970s, but which is still there, as a result of people taking a much more integrated approach towards local communities, being able to help people make a living out of their land without encroaching into the forest any further and on the back of that community engagement to be able to think about how to reconnect areas of the little bits of forest that remain to create bigger tracts, which would be much more resilient in the future in being able to hang on to their wildlife. And so this is really a story of social development and community engagement. And across the world, we can see many examples of this. And another one, which I wrote about in the book, which is, I find quite inspiring, at least, is the example of Costa Rica, which sought a route towards economic development that not only didn't involve deforestation, but included putting much of the forest back. And if you look at that country, between the 1980s and now the forest cover has doubled, so has the country's per capita GDP. And this was through the realization, literally, by the finance ministry in that country 30 years ago, that the forest was worth more for the nation alive than dead. And they have good reasons to think that in terms of their power sector, their electricity was coming from hydroelectric dams that were being powered by rivers topped up by rain forests. They found that they had vast quantities of clean water coming out of the forest that didn't need to be cleaned up in water treatment works. And then the real visionary opportunity that they spotted was for eco tourism. And so putting all these things together, and in the future, they may be able to participate in carbon markets too, they've managed to hang on to the forest, expand it, at the same time as grow their agricultural sector. They are a very major exporter of coffee, of pineapples and bananas. And they've blended all of these economic dimensions into a plan which is really about keeping the forest there for the national good. So if you want to have development into the future, keep and expand the forest. That's what the science and indeed the good practice is now telling us.

CURWOOD: Tony Juniper is Chair of Natural England and author of Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth's Most Vital Frontlines. Tony, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

Costa Rica is home to over 174 species of toads, salamanders, and frogs like the red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas). (Photo: Thomas Marent)

JUNIPER: My pleasure, Steve, it was a great joy to be able to sit and speak for a bit.

Related links:

- Rainforest: Dispatches from Earth’s Most Vital Frontlines by Tony Juniper

- Listen to LOE’s segment discussing the Pope’s Amazon Synod

- Listen to LOE’s segment on how healthcare and forest health can go hand in hand

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Golliwog's Cakewalk” on Kaleidoscope, HighNote Records]

[SFX]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week in the rainforest of Borneo in the company of orangutans.

[SFX]

CURWOOD: The huffing sound made by this adult male orangutan is an indication of extreme agitation, likely a response to the people recording him.

[SFX HUFFING SOUND THEN SMOOCHING SOUND]

CURWOOD: The smooching sound is a common noise orangutans make when they encounter something unusual or frightening like a predator.

[SFX]

CURWOOD: There are roughly 60,000 orangutans left in the wild and exist only on two Islands in Indonesia - Borneo and Sumatra. This recording comes to us courtesy of Wendy Erb at the Center for Conservation Bioacoustics.

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Golliwog's Cakewalk” on Kaleidoscope, HighNote Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth