November 29, 2019

Air Date: November 29, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Silent Killer Called PM2.5

View the page for this story

Ultra-fine particulate air pollution known as PM 2.5 is so small that it can work its way through the lungs into the bloodstream, and from there into major organs including the heart, brain, and kidneys. A new study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA, finds a link between PM 2.5 air pollution at levels considered safe by the EPA and the deaths of 200,000 veterans over a recent decade. Earlier research linked PM2.5 with many disorders, including heart attacks and strokes, and this latest study adds three previously uncorrelated specific causes of death: dementia, kidney disease, and hypertension. Ziyad Al-Aly is a nephrologist and epidemiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a coauthor of the study and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the findings. (09:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This holiday week, Peter Dykstra notes that there is hope yet for the highly endangered Vaquita porpoise, whose pups offer the potential for repopulation. He and host Steve Curwood also examine the recent Harvard - Yale football game, where students from both schools banded together in protest to demand that their respective institutions divest their endowments from fossil fuels. Heading further into the world of fossil fuels, Peter Dykstra reflects on the 20th anniversary of the Exxon Mobil merger and the company’s alleged efforts to bury climate science. (03:20)

Science Note: Toad Mimics Venomous Snake

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

If you want to make it, fake it: researchers have discovered that harmless Giant Congolese Toads (Sclerophyrs channingi) mimic the venomous Gaboon vipers (Bitis gabonica) that share their central African rainforest homes. The toads, which are the first toads known to mimic a snake, use a whole toady toolkit, as Living on Earth’s Don Lyman tells us. Their bodies mimic the heads of vipers, and they raise their hindquarters to mimic a viper’s strike pose, even hissing like a snake if anyone gets too close. (01:35)

Cosmic Crisp Apples

/ Enrique Perez de la RosaView the page for this story

A new variety of apples, the Cosmic Crisp, hits grocery stores around the country on December 1st, after more than 20 years of development by the Washington State University Tree Fruit Research Commission. The Cosmic Crisp is a descendant of the popular Honey Crisp apple, and its breeders hope it can complete the holy grail of apple qualities: Great taste, easy growing and harvesting, and a long shelf life. Enrique Pérez de la Rosa of Northwest Public Broadcasting reports on how orchards are taking special care to ensure the first crop hits the shelves as a winner that matches the hype. (04:55)

Brewing a Specialty Coffee Market

/ Crystal LigoriView the page for this story

Coffee is no longer simply a generic drink to wake you up as there is now a sizable market for specialty coffees with unique flavors. To link up coffee growers with that market and ensure they get a fair price, a Portland, Oregon-based nonprofit called the Alliance for Coffee Excellence started a coffee tasting “cupping” and auction. Crystal Ligori from Oregon Public Broadcasting reports on how this project, now celebrating its 20th anniversary, has increased the earnings of coffee farmers around the world. (07:50)

A Typical Carbon Footprint of Thanksgiving

/ Lou BlouinView the page for this story

Each November, Americans travel to share feasts with family and friends, and all of this consumption can come at a cost to the climate. The Allegheny Front's Lou Blouin investigates. (04:20)

Reflections on the Native American Tradition of Giving Thanks

View the page for this story

Thanksgiving is a time for American families and friends to gather and be thankful, but for Native Americans it can also be a reminder of the displacement, violence and disease brought by the white colonists. Joe Bruchac, an author and storyteller of the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe, joined Host Steve Curwood to reflect on Thanksgiving’s complicated legacy for Native Americans and the long Native tradition of giving thanks. (10:00)

Cranberries Take Center Stage

View the page for this story

For some, it wouldn’t be Thanksgiving without the cranberry sauce. Living on Earth’s Emily Taylor and Dennis Foley bring us this audio postcard featuring Leo Cakounes, a cranberry farmer on Cape Cod, and the voices of cranberry enthusiasts. (04:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ziyad Al-Aly, Joe Brushac

REPORTERS: Lou Blouin, Peter Dykstra, Crystal Ligori, Don Lyman, Enrique Perez de La Rosa

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

New research finds tiny particles of air pollution known as PM2.5 can be deadly, even at legal levels.

AL-ALY: So when we breathe PM2.5, it goes to our lungs, but because it's also so small, it permeates through the lung tissue into the bloodstream. And then goes to other organs, including the kidneys, the brain, the heart, the liver, the pancreas.

CURWOOD: Also, an elder of the Nulhegan Abenaki tribal nation of New York on how he views Thanksgiving.

BRUSHAC: Within our traditions here in the Northeast one of the most important things we start with is giving thanks. It's not the idea of Thanksgiving but the way it's been framed within American culture that's difficult for native people.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

The Silent Killer Called PM2.5

Industrial pollution in Bratislava, Slovakia. Smokestacks from coal-fired power plants and factories are a major source of PM 2.5 air pollution in middle- and low-income countries. (Photo: Dominik Dancs on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

There’s more evidence that supposedly safe levels of air pollution can actually be deadly. According to a study recently published in a Journal of the American Medical Association 200,000 deaths of military veterans were linked to long term exposure to ultra fine particle pollution below EPA acceptable limits. Epidemiologists compared the records of 4.5 million veterans who died over a recent decade to levels of ultra fine particulates where they lived. These pollutants are called PM 2.5 for their size, which is two and half microns or about 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair, and almost all of us breathe them in every day, mostly thanks to the burning of coal and the tailpipes of millions of motor vehicles. Earlier studies have linked PM 2.5 pollution with a wide variety of maladies ranging from heart attacks and strokes to asthma and dementia. But now this research conducted at Washington University in Missouri has found associations with a total of nine disorders, including hypertension and kidney disease. Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly is a coauthor of the study and joins me now from St. Louis. Welcome to Living on Earth!

AL-ALY: Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about what you found about the relationship between these fine particles found in pollution with disease and mortality.

AL-ALY: Sure. So we've known for a long time that PM 2.5, or ambient fine particulate matter air pollution is associated with all cause mortality, is associated with increased risk of death. And there have been a few causes of death that previously have been linked to ambient particulate matter air pollution, that's PM 2.5. But we didn't really know all the causes of death that were associated with PM 2.5 exposure. So we set out to define and characterize all the causes of death that are associated with exposure to high levels of PM 2.5. And we found in total nine. You know, several, as I said, have been characterized before, including deaths due to heart disease and deaths due to lung cancer and lung disease. But then a few are new, which include kidney disease, dementia, and deaths due to hypertension or elevated blood pressure.

CURWOOD: What was your resource for this study? How were you able to determine this?

AL-ALY: So we built a cohort of about 4.5 million participants from using a database at the VA, and then characterize the relationship between exposure to PM 2.5, and risk of death, all cause mortality, and ran risk of cause specific mortality, causes of death in core participants, and this is how we were able to, you know, figure out the causes of death associated with the PM 2.5 exposure.

Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly and his colleagues were able to find a correlation between PM 2.5 air pollution and hypertension, or high blood pressure, a previously unknown link. (Photo: Ryan Adams, http://homedust.com/, Flickr)

CURWOOD: Now over what period of time did you look at the exposure to the air pollution? Was it the week before they died, the two years before they died, how long?

AL-ALY: We were interested in more long term exposure to PM 2.5, and so we've taken annual exposure, sort of the average annual exposure to PM 2.5 throughout the duration of the study, which was more than 10 years.

CURWOOD: What's the level of exposure to fine particulates that we're talking about here? What are the numbers and what exactly is measured in that number?

AL-ALY: The numbers really vary. There are some people in the United States who are exposed to PM 2.5 of about five, and some about six and seven and eight, nine and 10 and 12 micrograms per meter cubed. So that's sort of a, it's a quantitative measure of evaluating the concentration of those particles in a volume of air.

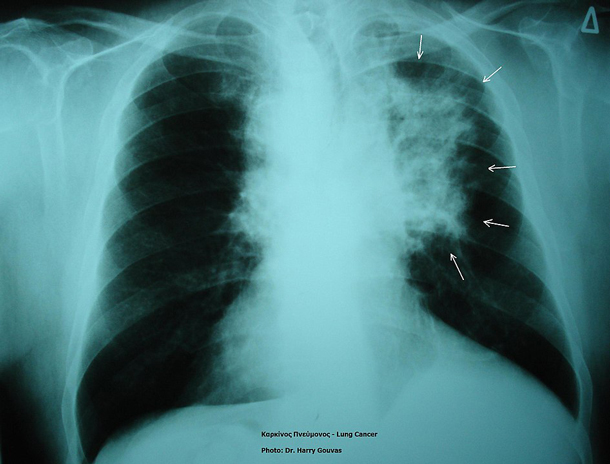

Lung cancer is also linked to PM 2.5 air pollution. (Photo: Δρ. Χαράλαμπος Γκούβας, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Okay.

AL-ALY: And obviously, the higher the worse, and the threshold that was set by the EPA is 12. So levels below 12 micrograms per meter cube now is considered from a regulatory perspective, considered safe.

CURWOOD: What does the World Health Organization say?

AL-ALY: The World Health Organization sets the level at 10 micrograms per meter cubed.

CURWOOD: So what's the mechanism of how these fine particulates cause illness and death?

AL-ALY: So when we breathe PM 2.5, it goes to our lungs, but because it is also so small, it permeates through the lung tissue into the bloodstream. And once it's in the blood, it circulates in the blood and then goes to other organs including the kidneys, the brain, the heart, the liver, the pancreas, where it may then affect them adversely.

CURWOOD: What parts of the country did you find a lot more mortality associated with PM 2.5, if there was any place?

AL-ALY: So it's really, the burden is not evenly distributed. You know, parts of the Midwest and parts of the South are more disproportionately affected.

Air pollution in Anyang City, Henan Province, China, where coal-fired power plants and factories produce much of the PM2.5 air pollution. (Photo: V.T. Polywoda, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So it's interesting that one finding of your study is that even when exposed to comparably the same amount of fine particulate air pollution, that black patients, black veterans were more likely to die from this type of pollution than white patients. What do you think is going on there?

AL-ALY: Correct. This is really what was eye-opening, for the same exact level of PM 2.5, let's say for PM 2.5 equals 10 micrograms per meter cubed, for the same exact level of PM 2.5, black patients, black veterans exhibited higher risk. And when we adjusted or controlled or held constant, you know, socioeconomic deprivation, you know, still race, you know, exhibited what we call that statistically an interaction. What that really means that black people in our cohort were more vulnerable for the same level of PM 2.5 than white people, irrespective of their socioeconomic background. That could mean a lot of things. One of the potential explanations for this is that perhaps minorities may have less access to resources or health care or preventive measures, or a means to mitigate, you know, the adverse consequences of exposure to pollution. And as a result, they become more sensitive to it or more vulnerable to levels of PM 2.5. And geographically, black people tend to also to live in an area where there is high pollution. So not only do they live in areas that have a higher level of PM 2.5, or higher levels of pollution, but they're also more sensitive to it, or more vulnerable to it. And that's really almost like the odds are stacked significantly against racial minorities. And that's sort of a piece of environmental injustice.

CURWOOD: Now what are the major sources of fine particulates, PM 2.5, now in the US?

AL-ALY: So in the US it's primary land traffic, it's really cars on the roads. In other parts of the world, industrial emissions, including power plants that are burning coal, are really number one. And there are places in Southeast Asia and also in India, where biomass burning, when farmers would actually burn the remnants of their fields to try to get rid of the agricultural byproduct of producing rice and other things, and that also produces a huge amount of PM 2.5. But in the United States, the primary source of PM 2.5 island traffic, meaning cars on the road.

In the United States, cars and trucks are the largest source of fine particulate air pollution. (Photo: Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine, public domain)

CURWOOD: Now what about wildfires, to what extent do wildfires raise fine particulate levels as well?

AL-ALY: They do contribute to it, but wildfires tend to be in the United States only regional and primarily on the west coast. They're not really distributed throughout the nation, and also really seasonal in the sense that they, you know, happen only for like about a month per year. And then they produce spikes in PM 2.5, and that generally affects the yearly average, but not really, not really very dramatically. But they're certainly a source of PM 2.5 exposure that need to be considered in the discussion.

CURWOOD: One of the things that's startling about your research is that these deaths are linked to folks breathing air that the Environmental Protection Agency says is supposed to be safe.

AL-ALY: So yes, I mean, you can read this both ways. So when one of the ways that you could read this is that most of the deaths that we found are actually below the EPA recommended level of 12. So one way to read this is really enormous success of the EPA and the Clean Air Act in reducing PM 2.5 in the United States, and that, you know, most of the PM 2.5 in the US now is below 12, so most of the health consequences that you see are below 12. So our other reading of this is that oh, you know, like most of the deaths now are below 12. So maybe we should think about how do we, or what's the right threshold for us to try to, at the same time not really curb economic productivity or curb progress, you know, encourage progress, but while at the same time also reducing, you know, the health burden or the health consequences or mitigating those to the extent possible.

Farmers prepare to burn crop residues in harvested rice fields in Punjab, India, prior to the wheat season. Crop burning contributed to an air quality crisis in northern India in October and November of 2019. (Photo: Neil Palmer / CIAT, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, air pollution, of course, is hard to avoid, but to what extent is there anything that people can do to protect themselves? Let's start with here in the US.

AL-ALY: Well, when it comes to the individual level, it's really hard to sort of advise people on wearing masks; maybe when there is like wildfires like in Northern California and you know, about a month ago or so, and maybe wearing masks and trying to stay in door when the fire is raging, as a lot of you know, smoke outside, or a lot of PM 2.5 in the air. But short of that for like the average daily, you know, life of a person living in a major city or living in the suburbs or living in rural areas in the United States. I think there's not a whole lot a person can do other than really participate in the discussion. As, how do we as a society, try to, you know, work together to, you know, come up with ways of while at the same time encouraging economic productivity, curbing air pollution, to the extent possible to reduce the health impact of air pollution.

Fine particulate air pollution has been linked to an increased risk of developing Type II diabetes. (Photo: momboleum, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly of Washington University School of Medicine, thank you so much for taking your time with us today.

AL-ALY: Thanks a lot.

CURWOOD: And by the way, when there is a strong rainstorm it can briefly wash fine particulates out of the air, so if you notice a clean fresh smell after a rain storm you may in fact be breathing cleaner air.

Related links:

- WIRED | “Air Pollution Is Still Killing Thousands of People in the US”

- Read the journal article in JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association

Beyond the Headlines

The vaquita porpoise (which means “little cow” in Spanish) is the world’s rarest marine mammal. (Photo: Paula Olson, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with environmental health news that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey, did you have a great Thanksgiving?

DYKSTRA: I sure did Steve, hope you did, too. I want to start with a little good news, possibly good news, at least. Vaquita porpoises are the tiniest marine mammals, they top out at about 110 pounds. They have some of the tiniest habitat, only a portion of the Gulf of California, of Baja California. And they probably also have the tiniest chance for survival. They're largely wiped out as bycatch by gill net fishermen.

CURWOOD: But there's good news you say.

DYKSTRA: The good news is despite the fact that the species may be down to as few as 20 animals left, there's been very, very little ability by Mexico to enforce conservation laws. In spite of it all, there are some young ones. There are some viquita porpoise calves have been spotted in the last few years. And they offer what biologists term as slim hope for a species that once was considered to have no hope at all.

CURWOOD: Well, let's hope those vaquitas keep having babies. Huh? What else do you have for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: We have a final score from New Haven, Yale 50, Harvard 43 climate protest arrests 42. Well, it's been decades since the Yale Harvard football game meant anything among college football elite. But this past weekend, the game often known as The Game, got some game of its own has hundreds of students from both schools non-violently stormed the field at halftime to call for both Yale and Harvard to divest their fossil fuel investments.

Harvard and Yale students non-violently stormed the field at halftime in the Yale Bowl stadium. (Photo: Timothy R. O'Meara / Harvard Crimson)

CURWOOD: Both of those schools have huge endowments. Harvard has north of $40 billion, I think Yale has $30 billion dollars.

DYKSTRA: The protests delayed the restart of the game, and most importantly, it forced ESPN to mention climate change.

CURWOOD: So I wonder if other schools will consider this?

DYKSTRA: Well, I'll be really impressed when the Oklahoma State football team sees a similar event at the T. Boone Pickens Memorial Stadium, or when a pro game is disrupted at Lucas Oil Field in Indianapolis.

CURWOOD: So yeah and of course T. Boone Pickens is a famous oil man.

DYKSTRA: That's right, and that'll be your Living on Earth sports report for today.

CURWOOD

Okay Peter. Let's have you take a look back in history and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: November 30, 1999, it's the 20th anniversary of the Exxon Mobil merger, actually a re-merger. It undid a major part of the breakup of Standard Oil from the work of Teddy Roosevelt and the trustbusters nearly a century before.

CURWOOD: Indeed, taking on monopolies back then. It's a pretty big company now.

DYKSTRA: It's a huge company now. In recent years, Exxon Mobil has been accused of burying its own climate change science and funding climate denier groups, in addition to being one of the biggest contributors to climate change throughout the world.

An ExxonMobil facility. The enterprises called Exxon and Mobil were part of the Standard Oil Trust that was broken up by the US government in 1911. And before they merged back into a common enterprise in 1999, Exxon and Mobil were fierce competitors. (Photo: Alf van Beem, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Indeed. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website loe.org.

Related links:

- More information about the vaquita and its endangered species status

- ESPN | “42 charged after protest at Harvard-Yale game”

- A 1999 account of Exxon’s merger with Mobil

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Network Music Ensemble, “We Gather Together” on Jazz Hymns, by Adriaen Valerius/Eduard Kremser, Network Music]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Coming up – helping coffee farmers get a better price for better coffee but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Science Note: Toad Mimics Venomous Snake

Subadult Comparison: A side-by-side comparison between a subadult Congolese giant toad and a subadult Gaboon viper from above, showing similar color pattern, shape and size. (Photo: courtesy of Eli Greenbaum)

LYMAN: There are well known examples of harmless animals mimicking deadly snakes. Burrowing owls can make a sound like a rattle snake. Benign snakes, like the

scarlet king snake, mimic the color patterns of venomous snakes, like the coral snake. But now researchers have discovered what they believe to be the first known case of a toad species imitating a venomous snake.

A young Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica) on the rainforest floor in Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Photo: Colin Tilbury, courtesy of Eli Greenbaum)

Scientists analyzed specimens of giant Congolese toads, and Gaboon vipers, Bitis gabonica, and found that the rear end of the toads looked an awful lot like the heads of the Gaboon viper. Both species evolved together 4 to 5 million years ago in the same Congolese rainforest. The toads also appear to have evolved two behaviors that imitate the Gaboon viper. The toads display a color pattern and shape that resembles the cocked head of a Gaboon viper in a strike position. And, when the toads feel threatened, they make a hissing sound similar to the Gaboon viper's hiss.

An adult Congolese giant toad (Sclerophrys channingi) from Democratic Republic of Congo ( (Photo: Konrad Mebert, courtesy of Eli Greenbaum)

[SFX GABOON VIPER HISS]

LYMAN: Scientists believe this unusual case of mimicry helps protect toads from being eaten by predators, which might be tricked into thinking a harmless toad the size of a fist is a 6 foot long venomous snake. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Giant Congolese Toad? Nope! This is the real thing, the Gaboon Viper (Photo: Tom Conger on Flickr, CC)

Related links:

- More about how the mimicry works

- Read the original scientific publication in The Journal of Natural History

- Click here to watch a deadly Gaboon Viper in action

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Cosmic Crisp Apples

A close-up view of the Cosmic Crisp. (Photo: courtesy of Proprietary Variety Management ©)

CURWOOD: Few things seem as pure and simple as taking a bite out of a fresh fall apple but growing apples is actually somewhat complicated. You can’t just throw some McIntosh seeds in the ground and expect to get a mac. You’ll likely get a hybrid that tastes nothing like the parent fruit. In fact, Johnny Apple Seed was likely sowing seeds for apple cider, not snacks or pie. Today, most apples are grown as a graft onto a root stock. A lot of trial and error goes into creating a new variety of apple but a new apple offering, the cosmic crisp, is getting ready to hit markets soon. Apple growers hope it will be as sweet and crunchy as a honey crisp but have a longer shelf life, making it easier to ship and store. Enrique Perez de La Rosa from Northwest Public Broadcasting has the story.

DE LA ROSA: Ask Aaron Clark how the cosmic Chris harvest is going and how answer with cautious optimism.

CLARK: This certainly I think, has got an opportunity to have some broad based appeal and, and, you know, everybody's pretty excited about it.

And I am too, but we'll see.

DE LA ROSA: That's because he's waiting for the apple to hit grocery stores at the end of the year. Clark is vice president of Price Cold Storage in Yakima and a fourth generation grower. Simply put, Clark is a businessman. Like many growers in the state Price Cold Storage sees a lot of potential in the apple. They've planted about 80 acres of Cosmic Crisp in their orchards compared to the 2000 acres of tree fruit they harvest that may not sound like much, but Clark says that's a lot for a new apple considering it takes upwards of $35,000 to buy and plant new trees.

A Cosmic Crisp apple tree (Photo: courtesy of Proprietary Variety Management ©)

CLARK: So this orchard you're looking at right here is a we got an easy a million four in it, and we're just getting our first crop.

DE LA ROSA: And that's not even all of it.

So what's so great about Cosmic Crisp? The Washington State University tree fruit research commission has been breeding Cosmic Crisp since 1997. Ines Hanrahan is executive director there, she says compared to its genetic parent Honey Crisp Cosmic Crisp is just a sweet and easier to grow. But though it's easier to grow Hanrahan says, growing new apples is not so simple.

HANRAHAN: Well, it's like any new thing you have to learn how to handle it doesn't mean that you can just plug some piece of wood in the ground that grows by itself you still have to manage it horticulturally.

DE LA ROSA: That's why the research commission spent weeks ahead of harvest teaching growers how Cosmic Crisp matures on the tree. If you take a bite out of cosmic before harvest. That's really good. It tastes it looks like it's right for picking. But Cosmic Crisp matures slowly which means growers have to rely on an iodine solution to see how much starch stored in the apple through photosynthesis has been converted into sugar. They spray the solution and sugars turned dark. Too much sugar or not enough means the apples might not store as well. But Cosmic Crisp can run into more serious challenges if not managed well from the start. Accor ding to WSU researcher Bernardita Sallato the variety is vigorous meaning it can grow quickly in most soil. But that can also mean it can grow too quickly. If not fertilized, properly mismanaged trees can develop something called blind wood.

Legacy Orchard in Washington State, one place where Cosmic Crisp apples are being grown (Photo: courtesy of Proprietary Variety Management ©)

SALLATO: Which is something like what you see here that you have a wood that it doesn't have any buds or a spores with no fruit so that's why they call it blind wood.

DE LA ROSA: So there's just nothing on it.

HANRAHAN: Yeah, but those things those challenges they can be managed.

DE LA ROSA: Sallato says most growers have avoided blind wood because it's cause and remedy are well known. Older apples like Granny Smith and Fujis also suffer from it. However, other issues are harder to manage because they're not as well understood by science. Take green spot, a cosmetic defect that doesn't change the taste of Cosmic Crisp, but could make it harder to sell. Sallato says it's probably just like bitter pit and Honey Crisp caused by a calcium deficiency. But she's not sure yet. She and other WSU researchers are looking into its causes.

SALLATO: If a the management of vigor or nitrogen can have some factor on that, the sprays of calcium with or without, so this many different factors that will be evaluated.

De La Rosa: Back at Price Cold Storage, Aaron Clark says he hasn't seen any of those issues. But experience has taught him that challenges are a natural part of taking an apple from the lab to the orchard.

CLARK: There's a big difference between test blocks and places that Wazoo would do and commercial farming. It's it's a lot of trial and error. It's just planting it and seeing where it goes.

DE LA ROSA: And this December It's going to market after 20 years and development

CURWOOD: That story of the cosmic crisp apple from Enrique Perez de la Rosa comes to us courtesy of Northwest Public Broadcasting.

Related links:

- Northwest Public Broadcasting | “What Does It Take To Get A New Apple Variety To Market? A Lot. And Cosmic Crisp Shows It”

- Click here to see if Cosmic Crisp apples are in a store near you

- Click here to read about the enormous ad campaign linked to the apple’s release

[MUSIC: Yehudi Menuhin/Stephane Grappelli/Max Harris, “Button Up Your Overcoat” on Menuhin & Grappelli Play Jealousy & Other Great Standards, by Lou Henderson/B.G. DeSylva/Lew Brown, Warner Classics]

Brewing a Specialty Coffee Market

A cup of joe is made by brewing roasted coffee beans, which are really the pits of coffee cherries. (Photo: Neil Palmer, CIET, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: At the end of your Thanksgiving feast you might have reached for a cup of coffee to go with that pumpkin pie, or poured one to get going as you headed out on the road for the drive back home. It costs around 15 to 20 cents to brew a cup of coffee at home, and coffee shops can charge way more, but the tropical farmers who actually grow the coffee typically get less than a penny for a cup’s worth of beans. But here is a change on the way, at least as far as a Portland, Oregon based non-profit is concerned.

Crystal Ligori from Oregon Public Broadcasting has the story.

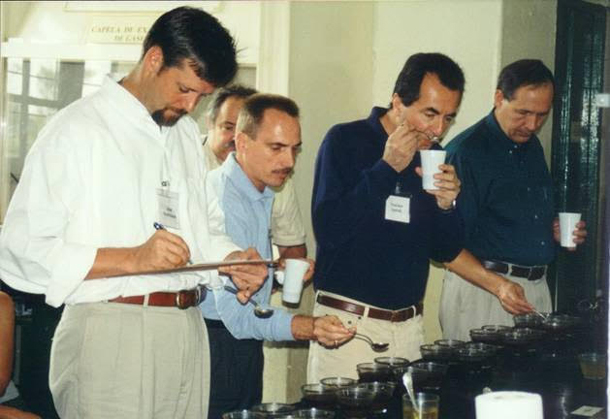

LIGORI: At an industrial building in southeast Portland, Steve Kirbach and Brian Freire are tasting coffee.

KIRBACH: had a nice weightyness like a tackiness to it. And then overall enjoy this coffee so I was an eighty seven two five on this coffee. Yeah, this was my favorite on the table. I also scored it eighty seven two five.

LIGORI: Kirbach is an 18 year coffee veteran and the director of sourcing and manufacturing at Coava Coffee Roasters. He and lab manager green buyer Freire do these cuppings multiple times a week, sometimes multiple times a day to evaluate their coffees.

FREIRE: Golden raisins and fig on the nose red apple, clove, brown sugar stone fruit hibiscus, dulce de leches and pear trail mix.

LIGORI: How we talk about coffee, how it's evaluated, scored and subsequently priced. It hasn't always been this way. In fact, people only started using the term specialty coffee in the 1970s. That's the underlying idea that much like wine, specific microclimates and coffee varietals produce different flavor profiles of coffee. Think the difference between a red delicious apple and a honeycrisp. You probably drink coffee without thinking much about where it starts. So you may not know that that coffee bean isn't actually a been at all.

SPINDLER: I think most people don't realize that coffee comes from a cherry. A lot of times the look on their faces is... What?

LIGORI: That's Suzy Spindler. She's an icon in the specialty coffee industry, who in the late 80s answered an ad in a Chicago newspaper with a pretty catchy opening line.

SPINDLER: Do you love coffee?

LIGORI: Spindler ended up working for the international coffee organization and in 1997, was tapped to be part of the gourmet coffee project. It was an effort by a group of trade organizations to study transparency in the supply chain in five countries, Uganda, Bolivia, Ethiopia, Papua New Guinea and Brazil. The idea was to get growers more money for producing better quality coffee, and in turn reduce the economic vulnerability for those coffee growing countries. Historically, coffee exported from a region was lumped together sometimes literally, without much thought on the type of coffee or how it was grown or produced. So Spindler and a colleague were tasked with finding out if Brazil, the world's largest coffee producing country, could grow that higher quality coffee. And it could, but changing the minds of people like importers and roasters wasn't easy.

Evaluating coffees at the first Cup of Excellence in 1999. Since then the Alliance for Coffee Excellence has held over 140 auctions in more than a dozen countries. (Photo: Courtesy of the Alliance for Coffee Excellence)

SPINDLER: We couldn't convince anybody that it was not just a fluke, it wasn't going to happen.

LIGORI: So they thought having a coffee competition in Brazil can be the answer. They’d bring judges into taste the coffees, rank them and award the best. But that idea quickly shifted.

SPINDLER: Well, at the end of the day, when we got to thinking about this strategy, we went well, what good is a certificate? You can't take a certificate to the grocery store. You can't take a certificate to the bank. What is it going to do to change coffee prices? Nothing.

LIGORI: Instead, they turn to the internet. This was 1999, just a few years after eBay started and was becoming a recognizable concept. They decided to build their own auction platform. They pick 10 coffees to auction off to the highest bidder.

SPINDLER: The rest is kind of history, I guess. I think the number one copy was certainly less than $3 a pound. And it just I mean, it went, Oh my gosh, oh my gosh.

LIGORI: That winning coffee sold for $2 and 60 cents a pound more than double the commodity market price for coffee. Here's why that's important. Coffee is sold on commodities markets around the world just like wheat, cotton, sugar and plenty of other agricultural products. But the system is flawed when it comes to coffee. For example, today's current commodities market rate for coffee was 96 cents a pound. But on average, it costs around $1 40 a pound to produce. o cup of excellence auctions help Connect growers with buyers who actually cared about and would pay more for higher quality coffee. That first auction started to change the whole mindset around where specialty coffee could come from. So with the help of the Brazil specialty coffee association, another auction was held, this time being called Best of Brazil.

.jpg)

Evaluating coffee or “cupping” uses a worksheet with eight categories: sweetness, acidity, mouthfeel, clean cup, flavor, aftertaste, balance and the overall score. (Photo: Tony Chen, Alliance for Coffee Excellence)

SPINDLER: And I'll never forget this day, sitting in the cupping room with the discussion and hearing one of the cuppers go, "what country are we in? Brazil doesn't produce this kind of coffee."

LIGORI: Spindler ended up co-founding the Alliance for Coffee Excellence to oversee the cup of Excellence Program. They've held over 140 auctions in more than a dozen countries. And this month, they celebrate their 20th anniversary.

Back in the cupping lab, the guys at Coava are evaluating everything from acidity to mouthfeel on a cupping form that looks a lot like a math worksheet. There's a specific process to cupping from how coarsely ground the beans are to the temperature of the water to that aeration or slurp of the brew. From a cafe in Oregon to a farm in Ethiopia, it's something that can be replicated anywhere. And it needs to be because it's how coffee across the world is evaluated now, by third wave coffee companies like Stumptown or Intelligentsia, to small micro roasters in Europe to the biggies like Starbucks or Pete's. Here's Kirbach again,

KIRBACH: Specialty coffee is from eighty and above. But there's a huge discrepancy between 80 and 86. Even within the smaller range of like 84 and above there are very distinct price tiers typically.

LIGORI: Coffees in a Cup of Excellence auctions must score 87 or higher. This past summer Kirbach was a head judge for a Yemen auction and the competitions are fierce. Before the auction even begins, judges evaluate up to 9000 samples with the top coffees tasted more than 100 times. But this world of specialty coffee can often feel disconnected from your everyday drinker.

KIRBACH: Somewhere down the line. It was established that $1 cup of coffee is okay. And that probably should have never happened. You know what I mean? Like that only happened because somebody was getting exploited.

The Cup of Excellence auction is a selective event in which 9,000 coffees can compete but only 30 can pass. (Photo: PhotoTony Chen, Alliance for Coffee Excellence)

LIGORI: The Alliance for Coffee Excellent showed coffee farmers that extra work was worth it. From being selective about picking only the ripest cherries to using different methods to process the coffee beans. In the end, people would pay more for better quality coffee. Here's Susie Spindler again.

SPINDLER: There's a lot of charities out there. There's a lot of NGOs out there. There's a lot of different kinds of organizations that try to help farmers. But the Alliance for Coffee Excellence if you look at the structure of it, what it does is it asks the marketplace to do the right thing for the farmers and just provides the structure in the middle of it to make that happen.

LIGORI: And after two decades the cup of excellence auctions have brought in more than $60 million for farmers.

CURWOOD: That’s Crystal Ligori from Oregon Public Broadcasting.

Related links:

- OPB | “How a Portland Nonprofit Brings Better Coffee to Your Cup”

- Alliance for Coffee Excellence: Click here to read more about specialty coffee

[MUSIC: Los Incas, “El Condor Pasa” on El Condor Pasa, by Daniel Alomía Robles, Warner Chappell]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Just how earth-friendly was the typical Thanksgiving feast.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Los Incas, “El Condor Pasa” on El Condor Pasa, by Daniel Alomía Robles, Warner Chappell]

A Typical Carbon Footprint of Thanksgiving

The traditional Thanksgiving Day meal might be a belt-buster, but it won't bust your carbon footprint score. (Photo: Jack Amick, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

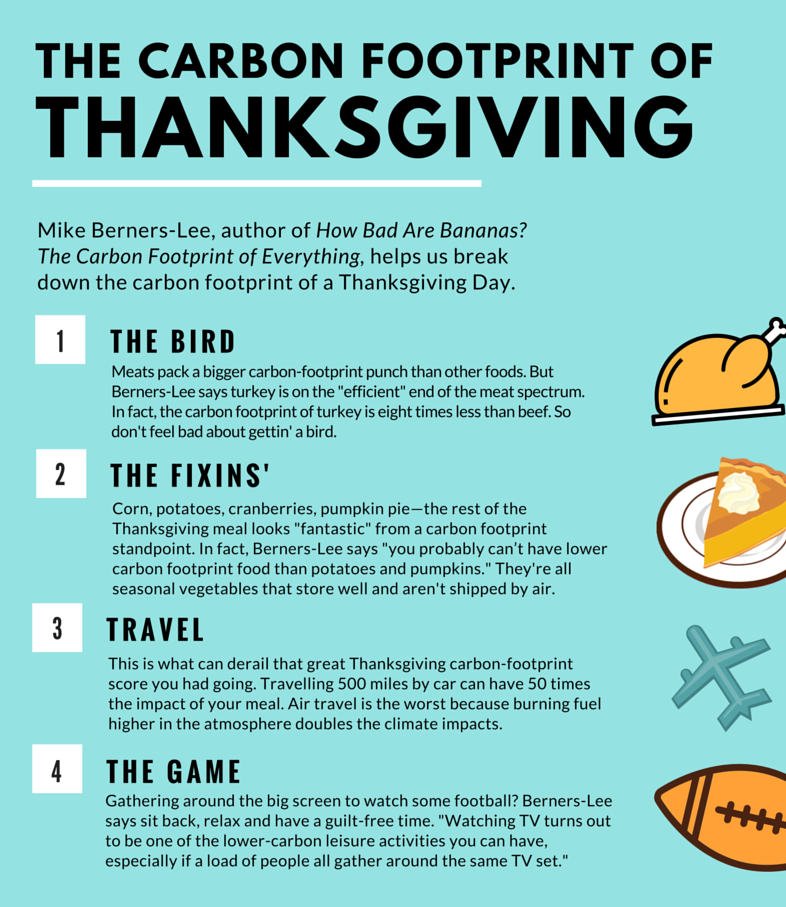

By now, for many of us that Thanksgiving turkey is history, and maybe we’ve even finished the leftovers as we visited with family and friends. Some like to ask just how much of an impact does this American holiday have on our planet, including reporter Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front. One year just before Thanksgiving he decided to investigate the carbon cost of a typical Thanksgiving feast.

BLOUIN: Turns out the guy who may know the most about the carbon footprint of an American Thanksgiving, hasn't ever experienced one himself.

BERNERS-LEE: I haven't actually. Although it doesn't look all that dissimilar from our Christmas dinner in the UK.

BLOUIN: This is Mike Berners-Lee, and he's considered one of the world's leading experts on carbon footprint of, well, everything. In fact, he wrote a book subtitled, the "Carbon Footprint of Everything". So earlier this week, I phoned him at his office in the UK to talk a little turkey.

BERNERS-LEE: Yeah, Sure, Ok. Well, turkey is a meat, and most of the time the thing to say about meats is that they’re quite inefficient way of having nutrition. But having said that, chickens and turkeys are very much at the efficient end of the meat spectrum.

BLOUIN: That’s because a Thanksgiving turkey can go from egg to a bird that’s 20 pounds or more in just 14 weeks. So they’re not really on the planet long enough to make that big an impact. And it turns out it doesn't even matter all that much if you go with a local bird, which only has to ship from the farmer down the road.

BERNERS-LEE: Well, it matters a bit, but it would still be fairly small compared to the actual footprint of growing the animal in the first place.

BLOUIN: In fact, Berners-Lee says transportation might only account for about 25 percent of the turkey’s total carbon footprint, assuming it’s not shipping by air. But bottom line—having a turkey on your Thanksgiving table is not all that bad. And the same goes for corn, potatoes, cranberries, pumpkins and a lot of the other foods that end up on your plate.

BERNERS-LEE: So, they’re seasonal vegetables, and they keep well. And you don’t have to do anything crazy like put them on an airplane. So they’re fantastic. In fact you probably can’t have lower carbon footprint food than potatoes and pumpkins.

BLOUIN: So all in all, the Thanksgiving dinner looks pretty good from a carbon footprint standpoint. That is, if you go traditional.

KRAUSS: Yeah, so, okay. This year is a little bit different. Little bit of a curveball. But there is no turkey.

BLOUIN: This WESA reporter Margaret Krauss. She agreed to let us dissect the carbon footprint of her Thanksgiving plans, which are still kind of coming together.

KRAUSS: There is a meat that will be grilled outside: maybe we’re doing bratwurst. Maybe we’re doing chicken. Maybe we’re doing steak?

BLOUIN: Whatever she decides to cook, it sounds like it’s going to be a bit of a fire drill. The plan is to get on a plane, and on Wednesday night, hit the supermarket to pick up some supplies when she lands.

KRAUSS: So check this: I’m getting on a bus that will take me to the airport that will take me to Minneapolis that will take to Salt Lake City, and then driving from Salt Lake City to Provo, Utah.

BLOUIN: So all in all a pretty big trip, and that—along with the alternative menu—could get Margaret into trouble according to Mike Berners-Lee.

BERNERS-LEE: Well yeah, red meats are a quite a lot less efficient. The carbon footprint of beef would be about 24 kilos of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilo of beef, whereas for turkey, it’d be nearer three.

BLOUIN: And the air travel is a real killer.

BERNERS-LEE: So a Boeing 747 will get through—I can’t remember the exact number off the top of my head—but it’s 100 and something tons of fuel per trip. So you end up with an enormous carbon footprint shared out between the passengers. And your friend has to take a few tons of it on the chin.

BLOUIN: Even worse, Berners-Lee says the fact that the fuel is burning higher up in the atmosphere doubles the climate impacts. So drive if you can, better yet, take a train. But how does the carbon footprint of Thanksgiving travel stack up against Thanksgiving meal? Well, Berners-Lee did a quick calculation on my 500-mile trip back to Michigan by car.

BERNERS-LEE: So you’re going through about 50 liters of gas, so that would be the same carbon footprint of turning up and finding your way through 50 kilos of turkey, which would be quite an achievement.

BLOUIN: Yeah; no way that’s happening, even with leftovers. And at my house, my mom has a pretty energy-efficient way for storing those. When the fridge fills up, as long as the Michigan fall weather is cooperating, she puts the turkey in her car too keep it cold. Pretty sure that method is keeping the planet safe from harm. Not sure I can say the same for us. I’m Lou Blouin.

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about food and the environment on The Allegheny Front

- How Bad Are Bananas?: The Carbon Footprint of Everything

- BBC | "Beef environment cost 10 times that of other livestock"

- The tricky truth about food miles

- NY Times | "Food Waste Is Becoming Serious Economic and Environmental Issue, Report Says"

[MUSIC: Arlo Guthrie, “Alice’s Restaurant” on Alice’s Restaurant (and The Best of Arlo Guthrie), by Arlo Guthrie, WMG (on behalf of Warner Catalog)]

Reflections on the Native American Tradition of Giving Thanks

Succotash is a traditional Native American dish consisting of sweet corn, lima beans and other shell beans. (Photo: Susan Lucas Hofman, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Thanksgiving is one holiday that most Americans feel free to celebrate. No matter what religious or cultural background we come from many of us gathered with friends and family on the fourth Thursday of November to feast on the foods of the harvest season. But its more complicated for the people at the center of the Thanksgiving story, Native Americans. There are nearly 600 Native American tribal nations in the US today, each with their own distinct traditions and culture. And to get some insight into some Thanksgiving traditions of the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe of Vermont and upstate New York, we reached out to storyteller and tribal elder Joe Bruchac. Joe, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BRUCHAC: Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Joe, you can tell us what's your feeling generally about the Thanksgiving holiday?

BRUCHAC: I would describe it as ambivalent. It was always very important to when I was a kid growing up but when I look at it from the viewpoint of Native people, especially here in the Northeast, there is a lot of cultural and historical baggage connected to it, that makes some native people describe it not as a day of Thanksgiving, but a day of mourning. Because of several things, of course, the dispossession of Native people that happened after that, supposed at first Thanksgiving, a number of Native Tribal Nations of the Northeast were either wiped out or driven from their homelands by the very European people who had originally been helped to by them to survive in this new land.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, we're taught in school that Thanksgiving is this holiday framed around the early white settlers, the folks that came to Plymouth, Massachusetts inviting Native Americans to feast as a way of thanking them for their help and learning how to survive in the new world. So how is the holiday taught in your family and your community as you grew up? And and how true does that narrative ring to you today?

BRUCHAC: Well, I think the complexity of it is is varied. For example, the idea of thanksgiving as a national holiday was first proposed or I should say proclaimed by Abraham Lincoln after the Battle of Gettysburg to celebrate a great victory for the union. Further, in New England, they say the first Thanksgiving that was declared for the Massachusetts colony by John Winthrop, the governor, was after the destruction and the driving out of the Pequod nation. So you can see how there'd be some complexity there.

Native Americans ate and used cranberries as a natural dye. Cranberry sauce would not have existed during the first Thanksgiving event since sugar brought by the Mayflower would have already been depleted by November 1621. (Photo: Jim Choate, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Indeed. And of course, it's this time of year that school kids have been learning about Thanksgiving and they maybe made even pilgrim hats and feather headdresses. How do you feel about about this way of teaching that part of American history?

BRUCHAC: Well, ironically, the Pilgrim hats they make are not the hats that the pilgrims wore. Okay. And the head dresses, they put on a little circles of paper with feathers sticking up, a lot of Native people feel that it's really not respectful of the way that we dress and it becomes a kind of parody because, as you know, so called ethnic minorities another term I don't particularly like, find themselves often parodied or stereotyped in majority culture. This is an example of, I think, kind of stereotyping that I'd rather not see.

CURWOOD: So there are a lot of things about the holiday that seemed to have changed over the years, but the foods that generally get set out on the table have remained the same. Of course, there were wild turkeys back then corn was grown squash. To what degree are these types of foods still a part of some Native American cultures?

BRUCHAC: Sure thing, one the favorite dishes of Northeastern Native People is called succotash, which is a mixture of corn, beans and squash, who are called the three sisters of life because they provide and have always provided so much support for our people. And of course, corn and beans and squash are three of the gifts of Native People to the world. Whereas Europeans tended to deal in taming animals and making cows and pigs and horses, none of which were here part of their life in the North American and South American continents they were incredible agronomists, people who did plant breeding and created dozens, in fact, hundreds of varieties of corn and beans and squash.

Maple syrup harvesting is a longstanding Native American tradition. A maple tree needs to be forty years old in order to produce sugar maple sap. (Photo: Stanley Zimny, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way back in those days in the Plymouth area at the coast, what we now call Cape Cod Bay I imagine there were plenty of lobsters. How did that feed into the menu the cuisine of Native Americans and the settlers at that time, do you think?

BRUCHAC: Without a doubt seafood was very important. Fish, crustaceans, such as the lobster, and other creatures from the sea were a very integral part of the diet. In fact, there's some question whether or not there actually was turkey at that first Thanksgiving but there, there certainly was seafood, there certainly, were those vegetables I've mentioned and I'm sure they also brought in deer because venison was a staple for the people at the time.

CURWOOD: Indeed, hey, um, tell me about your own family and friends. How do you celebrate Thanksgiving, if at all?

BRUCHAC: Actually, we do. We see it as an opportunity to bring people together to share food and I should point out that within our traditions, here in the northeast, one of the most important things we start with is giving thanks. It's not the idea of Thanksgiving, but the way it's been framed with an American culture that is difficult for Native people. And these Thanksgiving celebrations took place not just at the harvest time and November, but when the maple trees first escape their sap to make maple syrup, when various other plants and harvesting of various types was able to be part of the culture. So, that idea of harvesting and sharing and giving thanks is very deeply ingrained in our traditions. and it's certainly very much a part of my family. Every meal we eat we always begin with a Thanksgiving prayer.

The star of today’s traditional Thanksgiving dinner is usually a large roasted turkey, but it’s unknown if the same dish would have been served during the 1600s. Fish and crustaceans were bountiful at the time and would have formed part of the first Thanksgiving dinner. (Photo: Paulo O, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what is that prayer?

BRUCHAC: We give thanks to the Creator, for the bounty that we've been given. We give thanks to our families, for their health and their good well being. We give thanks to each other and to the land that sustains us. And, in fact, if you look among our friends slightly to the West, the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois nations. they say that the Thanksgiving address a very formal enumeration of all the gifts of life from the earth, to the plants, the animals, the winds, the waters, the sun, the moon, the stars, the creator. All of these things must be thanked formally before any important occasion can begin.

CURWOOD: Talking to you, Joe, I realized I should be giving thanks for maple syrup and maple candy. For whatever reason, it escaped me that there's a strong Native American connection to this.

BRUCHAC: And I was told many years ago by Dewasentah, Alice Papineau, the Head Clan Mother, the Onondaga Eel clan, that when we get that first maple sap, it is a medicine given us by the Creator, that if we drink that sap straight from the tree, our bodies are going to be healed from the wounds and the troubles of winter, which I think is a beautiful way to look at it.

CURWOOD: Indeed. And then traditionally, to what extent do you folks start to boil it down and make it into syrup and then of course the candy it can become?

BRUCHAC: Well, I could describe to some detail the traditional native way of doing it. You cut out Sort of a V in the tree, you put a little hollow piece of sumac there and collected in a bark basket which is watertight. And then you would pour it into a dugout canoe and by heating stones separately and dropping those red hot stones into the canoe full of sap, you'd boil it down and result in maple syrup which then if it was cooked further over a pot, you could turn into candy. In fact, one of the special treats of the wintertime would be to take very hot maple syrup and pour it on the snow which makes it immediately a little kind of candy that you can eat kind of like a snow cone

CURWOOD: And then you wind up with a bunch of sticky canoes?

BRUCHAC: Yeah, you would I guess set up with a sticky glue although you don't fall out as easily joke, joke.

Joseph Bruchac is an author and storyteller from the Nulhegan Abenaki tribe. (Photo: Erik Jenks)

CURWOOD: Well, Joe Bruchac you are an author and a storyteller by trade. I wonder if you have a short story about Thanksgiving or gratitude that you care to share with us at this moment.

BRUCHAC: I think what I'd like to share in fact I know what I like to share something by Tom Porter, who is an elder of the Mohawk Nation, a truly wise person. Tom said that when the world was first created, our Creator told human beings, there was one thing you must do before all others. It is a simple thing: give thanks. Give thanks before you drink water, give thanks to your friends for the things they do for you, give thanks to all of creation and all that you meet. Well, what happened then is it people became forgetful, they stopped giving thanks. And as a result, everything began to go wrong around them. That is when the creator set another messenger and this messenger brought various ceremonies that could be done to remind us of the importance of giving thanks. That is a very simple story. But one I think that is still true to us today. If we forget to give thanks and be grateful indeed, everything begins to go wrong.

CURWOOD: Indeed, we're speaking just after the Thanksgiving holiday, but what you're saying is, hey, we have an opportunity right now to give thanks.

BRUCHAC: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: Joe Bruchac is an author, storyteller and elder of the Nulhigan Abenaki Tribe of Vermont and upstate New York. Joe, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BRUCHAC: Oh, Ktsi Wliwini, Thank you so much.

Related link:

Joe Bruchac’s website -- learn more about Joe Bruchac’s stories and work

[MUSIC: Joey Curtin & Marc Cooper, “Wampanoag (People Of the First Light) on Soundtrack For America, CD Baby]

Cranberries Take Center Stage

Fresh cranberries must be dry-harvested, which happens before the wet harvest. (Photo: Pen Waggener, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: As we leave the end of the harvest season and head towards the winter solstice, we take a look at a culinary icon, the cranberry. The Cape Cod region of Massachusetts near Plymouth where the Pilgrims stepped ashore back in 1620 is famous for cranberries, though these days Wisconsin is the state that by far grows the most. Still, Living on Earth’s Emily Taylor and Dennis Foley headed to Cape Cod for this story.

CAKOUNES: My name is Leo Cakounes and I run Cape Farm Supply and Cranberry company.

[MUSIC: Sue Keller “Cranberry Stomp” from ‘Ol’ Muddy: Riverboat Ragtime-Era Piano Sounds’ (HVR - 2003)]

CAKOUNES: Naturally what I think of when I hear the word cranberry is my mortgage payment because we basically that’s what we do for a living is grow cranberries.

MAN: Thanksgiving time so cook them up for turkey.

WOMAN: Decoration with cranberries. I decorate during Christmas time with cranberries myself.

MAN: I suppose cranberry sauce. Having Thanksgiving dinner is definitely the theme.

CAKOUNES: There’s a lot of nostalgia with cranberries, associated with Thanksgiving and that’s understandable but for us it’s a crop that we grow for the purpose of making a living.

MAN: Well, I used to go wild cranberry picking on the Cape with my dad. He’d always take me up on the dunes and show me all the hotspots.

WOMAN: Umm fifth grade. I don’t know, I think I had a dream about a bog. I don’t know. It was kind of weird, but fifth grade.

GIRL: When I think of cranberries I think of coyotes because on Cape Cod there’s tons of cranberry bogs and around them thousands of coyotes live there.

MAN: Since I was a child. I think I was fascinated the first time I saw a cranberry bog.

MAN: The bogs and uh Cape Cod.

CAKOUNES: The harvesting process of cranberries is probably the most interesting process because that’s the time of year most people want to come and see a cranberry bog.

WOMAN: (singing) Did you ever go to the cranberry bogs? Some of the houses are hewed out of logs. The walls are boards that are sawed out of pine. That grow in this country called cranberry mine.

CAKOUNES: There’s two basic kinds of harvesting. There’s the dry harvest. The dry harvest is done first, usually mid September. It’s done when the bog has to be completely dry that means no dew or anything on it. The dry harvesting produces what’s called the fresh fruit. Which is the large cranberries that you buy in the store that the consumer ends up buying, the actual cranberry itself.

WOMAN: He eats them plain, right out of the box. He and his sister both love to eat the cranberries plain.

MAN: I actually eat them plain a lot. I remember going to the museum and seeing them bounce down the little stairway for grating. We’d just pop them in our mouth.

WOMAN: I feel very puckered up and I feel like I’m going to eat something sour. I’m not interested at all…. (laughs)

MAN: The first time I had real cranberry sauce made with whole cranberries I was blown away it was marvelous stuff.

A cranberry grower wet-harvesting cranberries in a bog. (Photo: Massachusetts Office of Travel & Tourism, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CAKOUNES: The second kind of harvest which is probably most familiar to people is called the wet harvest. And we drive a machine out on the bog which beats the berries off the vine and then coral them with either boards or a cranberry barrier. And then those berries are pumped or loaded into an open truck with a conveyor and then they’re shipped to the supplier. And they’re actually called processed fruit. Those berries become your concentrate for drinks. They become your cranberry sauce.

MAN: For years I thought cranberry sauce was the stuff shaped like a can.

WOMAN: When I was a kid the only cranberries we ate were out of a can. But my mom would just put it on the plate whole in this gelatinous mass, you know. And she’d open up one end and it would just ooze out the other end and be like slurping sounds.

MAN: Canned cranberry sauce is almost never good.

WOMAN: The stuff in a can. You just sort of squish it out of the can and it sits there and giggles on the plate.

MAN: Slice it.

WOMAN: That’s right and you slice it, you can’t even serve it with a spoon.

CAKOUNES: The market for fresh fruit hasn’t really increased that much. There are still some people out there who are still dedicated to buy fresh cranberries and serve them on their Thanksgiving table and we think that’s wonderful. But we are really working hard producing new products. Hoping we can get into the candy market and the cereal market which will pretty much help us year round as opposed to waiting for one Thanksgiving dinner to pay our bills.

CURWOOD: Our cranberry audio postcard was produced by Emily Taylor and Dennis Foley.

Related link:

About Leo Cakounes, cranberry farmer

[MUSIC: Sue Keller “Cranberry Stomp” from ‘Ol’ Muddy: Riverboat Ragtime-Era Piano Sounds’ (HVR - 2003)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth