December 6, 2019

Air Date: December 6, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Banning New Natural Gas Hookups

View the page for this story

As scientists warn that time is running out to curb greenhouse gas emissions and transition away from fossil fuels, some towns and cities are enacting bylaws to codify the use of alternatives to natural gas and oil for heating and cooking. Brookline, Massachusetts is the latest town and the first east of the Mississippi to pass a bylaw banning almost all new gas piping in construction and major renovations. Architect and co-petitioner Lisa Cunningham joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about the movement to get gas out of homes. (05:34)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the international rise of coal, with China’s big push to increase coal power and Russia’s Siberian coast playing an increasing role in shipping coal. In Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, two years of delays are preventing islanders from accessing the FEMA aid needed to recover after hurricanes Maria and Irma, and Whitefish Energy, a firm contracted to rebuild Puerto Rico’s electric infrastructure, is entrenched in legal battles. Finally, in the history calendar the two turn to President James Polk’s 1848 speech that noted the discovery of gold in California, which brought thousands of gold seekers West and launched California into statehood just a couple years later. (04:47)

The Outlaw Ocean

View the page for this story

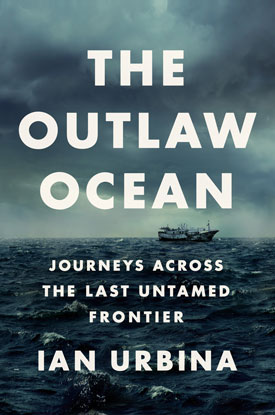

About seventy percent of our planet is covered by the oceans, but the high seas are among the least-explored frontiers on Earth. And lawlessness is rampant in this vast wilderness, with crimes ranging from illegal fishing to slavery at sea. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Ian Urbina wrote The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier to tell the harrowing stories of high crimes on the high seas, and he joined Host Steve Curwood at a recent live event in Boston. (20:40)

Eat Like a Fish

/ Elizabeth MalloyView the page for this story

Overfishing and climate change are hitting fish stocks hard, and at the same time most of the food grown and raised on land is carbon-intensive and unsustainable. The answer, says former industrial fisherman Bren Smith, is restorative ocean farming. In his book Eat Like a Fish, Bren Smith chronicles some of his adventures at sea and what he’s learned about sustainable food production as he has transitioned to ocean farming. To learn more, Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy caught up with Bren Smith on his boat off the Thimble Islands of Branford Connecticut. (12:20)

Remembering EPA Head William Ruckelshaus

View the page for this story

Only one person has ever served as an Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under two Presidents, and that’s William D. Ruckelshaus, who died the day before Thanksgiving. He was the first and fifth EPA Administrator, appointed by President Nixon in 1970, and returned to the agency during the Reagan Administration, to help “straighten the agency out” after a scandal over the mismanagement of the Superfund program. In a conversation with host Steve Curwood back in 2010, William Ruckelshaus reflected on his storied career. (02:59)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Lisa Cunningham, William Ruckelshaus, Bren Smith, Ian Urbina

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Lizz Malloy

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Tales of lawlessness and vigilante justice on the open ocean with Pulitzer Prize winning author Ian Urbina.

URBINA: I got a call from a source at Interpol who said, hey, have you heard about this thing going on down in Antarctica? It's the longest law enforcement chase on the sea. And it doesn't involve law enforcement. It's this conservation group who are sort of chasing this Interpol Most Wanted ship. And I said, wow, that sounds epic. Let me try to see if I can get on board.

CURWOOD: Also, restorative ocean farming for a sustainable food source and ocean health.

SMITH: We can grow our kelp from the surface vertically downward, right next to mussels and mussel socks, scallops and lantern nets, these are all vertical, and that is good because it has a small footprint you know very much like vertical farming in urban areas.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Banning New Natural Gas Hookups

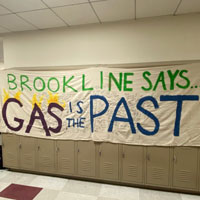

“Gas is the Past” banner made by Brookline high school students and signed by many members of the community. (Photo: Courtesy of Lisa Cunningham)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

As government leaders, scientists, and civil society from around the world meet at the UN’s COP 25 climate change negotiations in Madrid, some localities in the US are stepping forward to fill the gap left by President Trump’s refusal to engage. One example is Brookline, Massachusetts, an inner suburb of Boston with about 60,000 residents. Brookline is awaiting final state approval of a bylaw which would largely prohibit the installation of any new oil and gas pipelines in new or substantially renovated buildings. This legislation will be the first of its kind east of the Mississippi and it is expected to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 15% for the town over the next thirty years. Here to explain is Lisa Cunningham, co-petitioner of the bylaw. Welcome to Living on Earth!

CUNNINGHAM: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So you're an architect, what are you talking about doing in a building that you might be asked to design to get out of using natural gas?

CUNNINGHAM: So what you can do in terms of your heating and cooling needs is that you can use either air source heat pumps or ground source heat pumps, which many people refer to as geothermal. Right now, these systems are cost effective, and have been used frequently in building construction. The big change is that air source heat pumps used to be not applicable for colder climates in terms of being able to heat in very low temperatures. Now that's changed and air source heat pumps can heat buildings to minus 15 degrees and Brookline never gets that cold.

Three co-petitioners of Warrant-21 Lisa Cunningham, center (Mothers Out Front, Town Meeting Member, architect), Cora Weissboard, left (Mothers Out Front), Raul Fernandez, right (Select Board member). (Photo: Courtesy of Lisa Cunningham)

CURWOOD: Now, although you had almost a unanimous vote in favor of this, I'm sure there were some concerns that came up through the process. How did you address those, so you wound up with a virtually unanimous decision by the town?

CUNNINGHAM: That's a great question. So we actually listened very hard to what our constituents and also what various stakeholders were saying, the questions that they had, and then we actually came up with some exemptions to address people's concerns. So, one thing that we found out early on was that it's very hard to provide domestic hot water for buildings of over 10,000 square feet, so we made an exemption for that. We also made an exemption first for restaurant cooking, because we found out that although a lot of things are possible with restaurant cooking, there are some pieces of equipment that still aren't there in terms of cost. We also established a waiver process so that if there are certain projects that come up, it's very easy to apply for and get a waiver.

CURWOOD: So let me see if I understand your town bylaw, essentially, any new building or something that's being substantially renovated, really has to jump through some hoops if they want to have natural gas pipes.

CUNNINGHAM: Correct. You are allowed to keep your existing piping, but you are not allowed to install or move new piping.

CURWOOD: And what about the cost of this? To what extent is this going to raise costs for people who are doing renovation or new construction?

Warrant Article 21 received overwhelming support at a recent Brookline, Massachusetts town meeting and passed with a majority vote. (Photo: Courtesy of Lilly Cunningham)

CUNNINGHAM: Well, we actually did a lot of research into this. And to our surprise, we actually found out that these systems are essentially cost neutral. There's a very little variation in terms of installation costs. One thing that's also interesting as well is that for low income housing, there's a lot being done. In Brookline already two major building projects that have already started in town are installing air source heat pumps for their heating system and cooling. The residents are thrilled because they will actually be getting air conditioning along with their heating. And the Low-Income Housing Authority in Brookline actually made this decision prior to us bringing this Warrant article to the town.

CURWOOD: Now, I believe Berkeley, California was the first city to have strong restrictions on natural gas in new buildings and there's been kind of a ripple effect. What other cities and towns are you expecting to inspire with this move?

CUNNINGHAM: We are hoping to build a movement around this, the only way we can reduce our carbon emissions is to stop using fossil fuels. And so, we're very much hoping that other towns and cities will follow us. It just makes no sense to install systems that will last for 30 years, when we know we have to be ripping these systems out.

CURWOOD: What role does climate justice play in this bylaw?

CUNNINGHAM: Thanks for asking that question, it's a very important question. Climate justice is a very important part of this bylaw. We felt it was very important to make sure that underserved communities were getting the same benefits of this bylaw, that everybody else in Brookline would get. And we were completely satisfied by the fact that this is very affordable for low-income housing and also as you know, our climate crisis disproportionately affects people who are at risk already. And so this was a very critical part of our Warrant article.

CURWOOD: Lisa Cunningham was a co petitioner of the Brookline, Massachusetts bylaw restricting natural gas in new and heavily reconstructed buildings. Ms. Cunningham, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

CUNNINGHAM: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Greentech Media | “Rethinking Future Investments in Natural Gas Infrastructure”

- WBUR | “Brookline Proposal Would Ban New Natural Gas Connections”

- Click here to read more on Mothers Out Front

[MUSIC: Mason Williams and Deborah Henson Conant, “Classical Gas”]

Beyond the Headlines

China is the world’s biggest current emitter of greenhouse gases. (Photo: Kleineolive, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

CURWOOD: Well, it's that time in the program when we take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, I think, Peter, you there?

DYKSTRA: I'm here, Steve. I want to talk a little bit about coal capacity and coal use around the world. You know, we've heard so much, we've talked here so much about how coal is in decline in the US, power plants are closing or converting to renewables, converting to natural gas. Coal is also in decline in Europe in a big way. But both of those declines, which will help climate change are being offset by something that's going to cause more climate change. And that's that China is building so much more coal power capacity that all of the gains in the rest of the world are negated.

CURWOOD: Now that's not good news, Peter, what else do you have?

DYKSTRA: Well, I got some more not so good news from Siberia. The Northeast passage shipping route that's opening up with the melting Arctic along the Russian Siberian coast is gonna be the site of some more traffic of coal ships. India has a goal of drastically increasing its steel production. They need anthracite coal to do that, and one of the best untapped sources of anthracite coal is Siberia and Russia.

CURWOOD: So it sounds like the worse things get the worse things are getting. What else do you have today for us?

DYKSTRA: FEMA's aid to Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands has stalled. Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands of course were devastated by Hurricane Maria and Hurricane Irma two years ago. The Miami Herald recently reported that about one third of the claims by Puerto Rican homeowners to FEMA to help them rebuild have been denied. There's a tremendous amount of bureaucracy attached to this and a lot of people living with blue tarps instead of a real roof over their head from a hurricane that happened two years, two months ago.

CURWOOD: And now what's happened to rebuilding the electric infrastructure there in Puerto Rico?

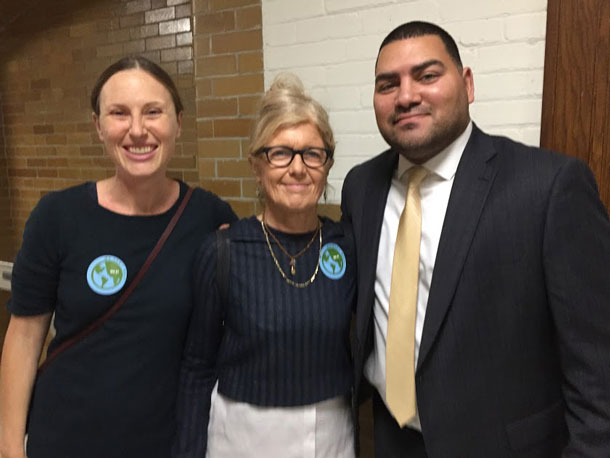

Whitefish Energy claims that the federal government hasn’t paid them for the work they’ve done so far in Puerto Rico. (Photo: Lorie Shaull, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, with infrastructure like the damage claims, payments in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands are way behind what FEMA's done in Texas and Florida. But with electric, you may recall that early on, there was a scandal involving a two person firm called White Fish Energy from Whitefish, Montana. They had a $300 million contract to rebuild the Puerto Rican electric infrastructure. This firm happens to be in the hometown of then Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. White Fish says they've already spent 126 million of that $300 million contract and that they've never been paid. They're suing the federal government and utilities that subcontracted to White Fish is suing White Fish, so it's a big, big legal mess.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and of course that contract was voided out I guess, by the federal government. But still, somebody has to pay. Hey, what do you have from the history vaults for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Going to go back to December 5, 1848, what was the equivalent back then of the State of the Union speech. President James K. Polk, who's not known for a whole lot, but maybe he should be known for saying something that jump started the growth of the state of California.

“The vast importance and commercial advantages of California have heretofore remained undeveloped by the Government of the country of which it constituted a part.” -James K. Polk, 1848 State of the Union Address. (Photo: Cornell University Library, Flickr)

CURWOOD: And that was?

DYKSTRA: He talked about gold being discovered in California, specifically at Sutter's Mill not far from Sacramento. And here's what he said: "The explorations already made warrant the belief that the supply is very large, and that gold is found in various places in an extensive district of country."

CURWOOD: Of course, people like gold then and even now, what happened?

DYKSTRA: 60,000 people made it to California in the year 1849 alone. And bear in mind, these aren't people who took the Transcontinental Railroad, because there wasn't one. They didn't take a relatively easy voyage through the Panama Canal because there wasn't a Panama Canal. Most of these folks went all the way around South America, around Cape Horn in a journey that sometimes took several months.

CURWOOD: So 60,000 people, that was enough to make a state right?

DYKSTRA: That's right. The beginning of 1848, California was still Mexican territory, it was ceded to the US. The gold strike happened later in the year, the Gold Rush happened in '49, and by 1850, California became the 31st state.

CURWOOD: Well, that's history for you. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living On Earth website, loe.org

Related links:

- China’s role in the global landscape of coal

- Coal mining projects on the Taymyr Peninsula pose a serious threat to wildlife

- A rundown of why it’s difficult for Puerto Rican homeowners to receive FEMA aid

- JEA’s (Jacksonville Energy Authority) lawsuit against Whitefish Energy

- President James Polk’s 1848 State of the Union Address

[MUSIC: Phil Cunningham, “Ceilidh Funk” on The Palomino Waltz, traditional arr.Phil Cunningham/Foss Paterson]

CURWOOD: Coming up – the risky business of reporting about crimes on the high seas. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mason Williams and Deborah Henson Conant, “Classical Gas”]

The Outlaw Ocean

The first story in The Outlaw Ocean focuses on the chase by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society of the Thunder, an alleged outlaw fishing vessel. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

About seventy percent of our planet is covered by the oceans, yet we know more about the surface of the moon than the deep ocean. With such little attention from society it’s also no surprise that lawlessness is rampant out on the open ocean, with crimes ranging from illegal fishing to slavery at sea. New York Times investigative reporter Ian Urbina spent a number of years researching and writing his new book, The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier. At times he risked his life in his quest to shed light on the dark corners of our seas. Ian recently joined me at the New England Aquarium near our Boston studios for a live event to share some of his stories.

CURWOOD: Ian, let me just start by asking you. The Outlaw Ocean; to what extent do we understand that there's no law out there? I mean, in this society, we live where, hey, if you have a parking ticket, they come for you and they boot your car. I mean, there's a whole system of accountability. And yet out there, there's not.

URBINA: Yeah, so, I approached this space both as a frontier and as an outlaw, by which I mean an extralegal space. It's not the case that there are no laws. There are lots of laws, but the laws are often written in a murky or contradictory way. And then also, laws are only as good as their enforcement. And especially on the high seas, in international waters, there's no, you know, police force that is out there patrolling. So while there are isolated cases of enforcement, they're rare.

The Outlaw Ocean shares stories of the high seas, where a lack of law enforcement allows lawlessness to run rampant. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: You decided to...and forgive me about this pun...bookend Outlaw Ocean with stories about the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. What about their journey stood out to you, and especially you have to tell us the story of the Thunder.

URBINA: Yeah, so for those who don't know, Sea Shepherd is this interesting organization, self-described as a vigilante ocean conservation group. It's an organization that has a large fleet of ships and they go around the world patrolling. And so the book is, as you say, bookended with two Sea Shepherd stories. The front story is about Sea Shepherd's campaign to chase the world's most wanted illegal fishing vessel, called the Thunder. And then the last chapter of the book is a look at a very different campaign, which was Sea Shepherd's harassing of Japanese whaling ships that are whaling, arguably illegally on high seas. And so the Thunder - the bottom line with this story was that there has been this purple Interpol list which essentially is a sort of arrest-on-sight list. And ships would be put on this purple list if they had engaged in demonstrable, repeat illegalities over a length of time. And the Thunder, by some metrics, topped the purple list because it had well-documented decade worth of illegal fishing largely in the Southern Ocean, largely aimed at the Patagonian toothfish, also known as Chilean sea bass, and to the tune of $67 million. And Sea Shepherd said, it's very frustrating that there is this list out there. And yet these ships, to a large degree, are allowed to operate without difficulty. They catch their fish legally or illegally. They go into port, they offload, and they go on, and no one ever arrests them. So Sea Shepherd said, we'd like to do something about it. We'd like to sort of show governments that A) we can find these guys and B) then once we find them, we're going to harass them. And that's different from their whaling campaign where they would actually ram the Japanese and do more aggressive things. On this mission, Sea Shepherd decided we're not going to ram them, we're just going to trail them and every time the ship attempts to enter port, we will raise a stink. You know, contact the media, embarrass the local government, et cetera. And the first task was let's start with the Thunder. It tops the list. We got to find these guys. Sea Shepherd did that within two, three weeks; found the Thunder, nets in the water in an illegal space in Antarctica and thus began this sort of epic tale of what became what some folks have said is the longest sort of nautical law enforcement chase in history. And what occurred was these two Sea Shepherd ships, the Bob Barker and the Sam Simon followed and harassed the Thunder over the course of 110 days and over 10,000 miles from Antarctic waters all the way up to the coast of Africa. And spoiler alert, ultimately, after a chase that involved the Thunder going through really perilous ice fields that most folks usually circumvent, they went straight to the middle, you know, Category Four storm that normally ships wait until it passes, the Thunder went through all, trying to lose their tail essentially. But at some point, the Sea Shepherd guys saw the Thunder guys putting their nets back in the water. They cut the nets and took them and the Thunder turned around and began chasing the Sea Shepherd guys. And so it was this really dramatic escapade and ultimately culminated...uh, shall I?

CURWOOD: Well, wait, you were there, though, for part of this. Tell us how you get aboard this, and what you do to get this story.

URBINA: Yeah, so I got a call from a source at Interpol who said, hey, have you heard about this thing going on down in Antarctica? It's the longest law enforcement chase on the sea. And it doesn't involve law enforcement. And I remember thinking, I don't even understand what that means. But I'm interested, you know, and so I said, tell me more. And he said, it's this conservation group who are sort of self-deputized as vigilantes, and they're chasing this Interpol Most Wanted ship and it's getting really hairy and it's been going on forever. And there are all these interesting shadow players involved. And I said, wow, that sounds epic. Let me try to see if I can get on board. I contacted Sea Shepherd, convinced them to help me think of a way for me to get on board the chase without... obviously, the ships couldn't leave their mark, leave their target, so they couldn't come pick me up and then return because they'd lose their target. And so we had to figure out a method for me to get out to certain coordinates that they likely were going to pass through, and then they would quickly pick me up and fall back in line. So that was a challenging task in and of itself. And ultimately, though, we were able to get to those coordinates right at the deadline, got on board, and then I was embedded with them for a while so I could chronicle the story. The story that ends with the Thunder...

The Thunder as it sinks, shortly after it apparently ran out of fuel following a lengthy chase. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: Well, but before you get to the end, talk about how you got between the two Sea Shepherd ships to work on the story.

URBINA: So, imagine Navy level ships, and they have high sides. And so the Sea Shepherd vessels obviously don't want to stop at any point. And so the photographer and I wanted to be able to chronicle the experience from both ships, so we had to move back and forth between them. And what that typically means is you get in a smaller boat, and they have a crane that lifts the small boat, and sort of puts it on the water while they're moving. And then you climb down a ladder, and you get in the fast boat. And the fast boat then takes you to the other side, and you do the same thing in reverse. And that ladder process was definitely hair-raising, and especially for my photographer. The funny thing was... this was when I was at the Times, and we had planned to fly this photographer from Brazil, to Ghana, where we were leaving from, and we couldn't get a visa for him in time. So my fixer in Ghana was this young guy who happened to tell me at the last minute, hey, I know how to click a camera. Do you want me to be your photographer? And I said, sure. Are you sure you want to go to sea? I don't know what this is going to be like, it's really... And he said, sure, why not? So I brought him along. And he was amazing. But we were on the vessel and at that very moment, when we were first going to switch vessels, as he was climbing over the railing, he turned to me and said, you know, Ian, thank you so much. This has been the experience of my life. And I said, you're quite welcome. He said, by the way, I don't know how to swim.

And I just remember thinking, geez, this guy's life is going to be on my conscience.

Rebecca Gomperts is a Dutch gynecologist and founder of the Women on Waves organization which provides abortions in international waters offshore of jurisdictions that ban voluntary pregnancy termination. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: So, you know, I think one of the most striking facts of your story, though, the Sea Shepherds really are breaking the law, they are vigilantes. So, as you've done the research for this work, how often did you have to deal with these sort of morally and legally gray areas?

URBINA: In some ways, the target of the series was the morally and legally gray area. And so as often as I was dealing with it, I was spot on where I wanted to be. And most of the more interesting characters in the book are in that gray space. Whether it's Rebecca Gomperts, a character in the story who provides abortions using a loophole in international law to ostensibly legally provide these abortions, here again, kind of a textbook example of character who's using the law to beat the law.

CURWOOD: Okay, so you have to tell us the story.

URBINA: Yeah, so Rebecca Gomperts, a gynecological doctor, Dutch citizen, worked for Greenpeace for a number of years. And in that work saw some troubling situations with girls and women who needed abortions and could not get access to them. And so she started her own organization called Women on Waves, which essentially, for the past decade and a half, two decades, has operated a ship that goes to countries where abortion is both illegal and often dangerous. And she and her team come into national waters, into port. Usually, surreptitiously, quietly plugs into sort of an underground network of healthcare providers who know of cases of girls and women who are in need, and then quietly brings these women and girls out to international waters. And because the way that maritime law works, such that when you're outside of national waters, the law that applies is the law the flag that you fly. And because her ship is flagged to Austria, the minute the ship would get outside of national waters into international waters, then it becomes legal for her to administer RU-486, pills that would cause an abortion. So, she would do this whole process very quietly, then return the young women back to shore and make sure their anonymity was safe. And then she would hold a press conference to sort of instigate a debate. And that's usually when she would get kicked out the country, as you can imagine.

Ian Urbina (left) and Rebecca Gomperts (right). (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: I imagine. So, I have to ask you another adventure story. I think you said your mother swallowed pretty hard when you told her that you were going to Somalia.

URBINA: She was none too pleased.

CURWOOD: And not to spoil the story necessarily, but well, you can tell us whether or not mom was right.

URBINA: Mom is always right, for the record. Yeah. So I told mom very little about actually where I was going before I left. I just said, I'm going to go to Kenya and then I might dip into Somalia. But that's as much as I said. Yeah, the Somalia story was an example of a story where I went in aiming to tell one story, which was actually going to be a good news story about an unusual, successful case of law enforcement where the Somalis and the Kenyans had gotten along and worked together and they caught these repeat offenders. And I did everything by the book because there had been some really bad cases of kidnapping of reporters working on this very topic and so I had permission from the key tribal leaders, et cetera, et cetera. Within a week of being in Puntland, which is mildly put, sort of what Texas is to Washington DC, Puntland is to Mogadishu. In the sense that it is part of the country but, no offense to Texans in the room, but very proudly, defiantly kind of autonomous. And in Puntland's case, it's also the launching zone for a lot of the illegality. So, it's hard to write a book about the outlaw ocean and not go to Somalia, and not go to Puntland specifically. But it's very hard to get into Puntland. The roads are run by ISIS and Al Shabaab. So, you've got to fly in, you can't go by road. And then when you're in there, you got to be really careful about who your security is, et cetera, et cetera. And I thought we had it all set up. The short version, everything went upside down. We ended up losing our security, being told we needed to leave, but there was no plane out, and we had no way to get out. So, we had to hide on the roof of our compound for a while until we could sort of sneak our way out and wait for a plane to come get us.

In the port of Bosaso, a team of guards prepares to head offshore and up the coast of Puntland, Somalia. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: So, there you are hiding on the roof. You've ordered up some security to escort you out to the one plane in the next two or three days. Take us to that moment. What do you hear?

URBINA: Yeah, so I had a special satellite device, so I was still able to text with sources. And the CIA has a drone base not far, and I knew some people over there, and there were no Westerners in our area. And Shabaab was moving in and blowing stuff up, heading towards the compound where we were and I was getting a lot of intel that was saying, you know, there's a lot of chatter about you guys. Everyone knows you're in there and it's not good, and you need to get out quickly, but we had no way out. And I had a fixer who was an American, based in Kenya, who knew the fish scene. I had Fabio, my Brazilian photographer and myself. And the intel we were getting streaming in was saying, you got to get out, you're persona non grata. The Puntland government said they are more than displeased with you, because they don't want you investigating these Thai vessels that are there and they're convinced you're CIA, et cetera, et cetera. Then we started getting even more worrisome intel, which was that within our security detail, we had about 20 guys, there were folks who were loyal to the president of Puntland et cetera. And so our threat was internal, not just external. So then I got really nervous. We had this meeting with the head of security at the compound and myself and the one guy that I really trust to... a guy named Tigey who was a tribal kind of figure and and very loyal and probably saved my life. And Tigey and I decided our plan was to make it look like we were still in the room. Because there was a courtyard that could see where we were staying. Leave the lights on, pull the drapes, make it look like we're staying there, let all of our security go except for Tigey's three cousins, who he knew to trust. And then we would quietly go to the roof and hide out there, but very few people would know we were there. And if a hit occurred, it would hit on our room. And then we would do what? I don't know, I guess sort of try to run, but where to? These are not questions I had clear answers for. So that's exactly what we did. We hid up on the roof for our final night. And there was a plane that was going to be brought in early for us. And we just needed to make it to the next morning. And so we hid up there for that night. Then, the next morning, our plan was to get certain guards that Tigey could call in to help us get to the airport. The roads from where we were to the airport were sort of very narrow roads, you're in a fishbowl. And these were the very roads that we would have to go through to get to airport and there was really only one route we would follow. And everyone knew that there was one plane that had come in. So, everyone knew when those Western guys were going to leave the compound, because there was one plane. So it just seemed like a formula for us to get hit. And so our hope was to leave really early with some reinforcements. That plan didn't go well either, because the plane said they were going to leave early, and we had to go with no guards and just sort of make a run for it. And during our run, we were stopped by two pickup trucks full of armed guys who were not in uniform. And I thought, we have these SOS buttons on our iPhones and I had given the fixer and the photographer clear orders on if we got stopped and pulled out, here's what we should all do. And there we were, stopped and being pulled out. And that was, you know, kind of the scariest moment of the time, but in the end, it turned out that these were Tigey's guys. So we were very lucky and these guys sort of pulled us out, checked us out, and then put us back in and we raced to the airport and got out.

Ian Urbina (center bottom) was told to sit on the floor of the boat to avoid being seen from shore as he and his team travel up the coast of Puntland. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: Did you kiss the airplane?

URBINA: [LAUGHS] I kissed the ground, I kissed many people. I can't even remember who.

CURWOOD: There's a line at the end of your book. And it's going to be better in your voice. This is from page 408 of The Outlaw Ocean.

URBINA: Yeah, so. The ocean is outlaw not because it is inherently good or bad but because it is a void, like silence is to sound or boredom is to activity. While we have for centuries embraced and touted the life that springs from these waters, we have tended to ignore its role as a refuge of depravity. But the outlaw ocean is real, as it has been for centuries, and until we reckon with that fact, we can forget about ever taming or protecting this frontier.

CURWOOD: So, what's the fix?

URBINA: What's the fix?

A crew of possibly enslaved Cambodian boys and men work on a Thai fishing ship, several hundred miles off the coast of Thailand in the South China Sea. (Photo: Courtesy of The Outlaw Ocean)

CURWOOD: Yeah, some say the ocean is just too big. It's too vast to be brought to heel. And you would say?

URBINA: I would say, if I wrote a book about injustice, right, and someone said, so what do we do to stop injustice? I would probably say we start by not asking that question, because it's too broad. And I couldn't possibly answer at that altitude. Similarly, what do we do to fix the ocean? That's kind of like how do we win the war? And I would immediately say, don't think about the war. Just choose your battles, and figure out which of the specific components of that war are the ones that you feel most motivated to tackle, right? So again, if it's ocean dumping or plastic pollution or murder or protection of seafarers, or, you know how we handle stowaways post 9/11 or seafood supply chains. I think the smartest move is to not think about the war. I do think there are some solutions that are emerging that traverse those silos, that sort of cross them, that would benefit the environmental and the human rights and labor issues. So, for example, if you think of the aeronautics industry, if you were to walk up to a pilot of a 747, and say, so, you've called ahead, they know you're coming, we'll see you your entire route, you're going to keep that thing on. We know what cargo you're carrying. We know everyone on board, all their names are registered on both sides, et cetera, et cetera. These answers would be readily and easily answered, right? In much of the world, in the long-haul fishing realm, if you asked a boat captain these questions, they would look at you like you were crazy to even be asking those questions. So, there is a cultural issue that needs to be confronted that's in the maritime space that allows this realm and those who operate in it a certain level of liberty. That is a core problem in my view. And so, whether ships have a unique identifier, a license plate that everyone can see, that stays the same, and there are serious consequences if you attempt to change it, that would be one step. Not being normal or allowed to turn off your transponder and, in fact, imposing transponders that you can't turn off at all; another thing that could be a big step forward. These are lofty ideals, difficult to actually implement, but could be a big step forward to actually tracking who's moving what, where and how and what's happening to the fish and the people that work there.

CURWOOD: And I have to ask this as well. Through all these difficult situations, share with us an up lifter.

Ian Urbina is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and author of Outlaw Ocean. (Photo: © Jabin Botsford)

URBINA: There's a lot of beauty out there, both in the space and the people. That's why I often say like, it's extralegal. Even sometimes it's purely illegal, but it's not always bad. The characters I met along the way, the sort of underground network of anti-trafficking advocates who specialize in helping sea slaves, essentially, debt-bonded or even just shanghaied workers, some of them shackled, escape is really inspiring. And often those guys are breaking laws. The Rebecca Gomperts types that are out there trying to use the law in creative ways and use the high seas in creative ways to help in their view, I think are really impressive. And then also just, for all the gloominess of the reporting and the abuses it highlights, for the most part, the crew on these vessels, some of them as young as 13, their will to survive, their sort of scrappy ingenuity to make the time pass, their camaraderie, their sense of humor, their work ethic is really inspiring. They're not sort of downtrodden, somber faced, even in the midst of really harsh conditions. So I find those things inspiring.

CURWOOD: Ian Urbina's new book is called The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier. Ian, thanks so much for spending the time with us.

URBINA: Thank you.

Related link:

The Outlaw Ocean’s official website

[MUSIC: Marian McPartland, “Yesterdays” on Timeless, by Otto Harbach-Jerome Kern]

CURWOOD: Coming up –the life and legacy of William Ruckelshaus, the first EPA administrator of the United States, just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Marian McPartland, “Yesterdays” on Timeless, by Otto Harbach-Jerome Kern]

Eat Like a Fish

Picture of Bren Smith cleaning oysters. Oysters sequester carbon from the ocean to manufacture their shells. (Photo: GreenWave)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

As we heard before the break, life on the high seas can be unforgiving and even deadly. But plenty of rough and tumble fishermen choose a life on the ocean. A love of the sea and the adventure it can provide has been drawing in fishermen for generations. One of them is Bren Smith. Bren Smith left high school in Newfoundland when he was just 14 and took up work on fishing boats in the open ocean. In his new book, Eat Like a Fish, Bren chronicles some of his adventures at sea and his new job, farming. And to be clear he’s now an ocean farmer and founder of Green Wave, an organization dedicated to sustainable and restorative ocean farming. To learn more, Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy caught up with Bren Smith on his fishing boat in the Thimble Islands off Branford Connecticut.

MALLOY: Alright, so can you tell us a little bit about your restorative ocean farm? What are you doing here?

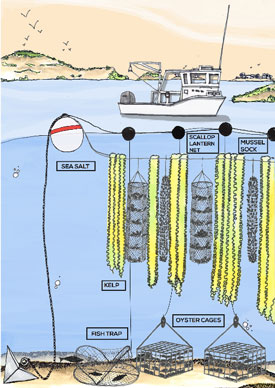

SMITH: I used to be a commercial fisherman, and over the years have been on this journey to try to figure out: what does it make sense to grow in the ocean? Like ask the ocean? What should we grow? Like, how should we farm it? And if you ask the ocean that it says something pretty simple, it says: Why don't you grow things that you don't have to feed and don't swim away. And so we're out here, trying to reimagine aquaculture and grow a mix of shellfish and seaweeds and grow as many things that, as we can in a 20 acre area, but not any species, species that restore rather than deplete ecosystems. So something like our kelp soaks up five times more carbon than land based plants, it's called the Sequoia of the sea. Our shellfish filter nitrogen out of the water column, where our farms are really creating these really dynamic ecosystems that mimic Mother Nature.

3D Ocean farming works by taking advantage of space and incorporating seaweed, scallops, oysters and clams. (Photo: GreenWave)

MALLOY: That's awesome. And why do you call it 3D ocean farming?

SMITH: So we call it 3D ocean farming because it uses the entire water column. When you're farming underwater if you just create a simple rope scaffolding system of buoys, anchors, and ropes, it's really cheap, right, doesn't cost much money to start one of these farms, but it's a really efficient use of space. So we can grow our kelp from the surface vertically downward, right next to mussels in mussel socks, scallops in lantern nets, these are all vertical and then we have oyster cages down below and clams in the mud and just really using every bit of water we can and that's good because it has a small footprint. You know, very much like vertical farming in urban areas.

MALLOY: Why do you feel like you are in this position where you are now with restorative ocean farming?

SMITH: So I grew up in Newfoundland, Canada, little fishing village called Maddox Cove right next to a fisherman's Co-Op, you know, kids were selling cod tongues door to door, dropped out of high school when I was 14 and headed out to sea, fished in Gloucester, Lynn Massachusetts -- tuna, lobster -- then headed to the Bering Sea, where I fished cod and crab. And I was working at the height of industrialized fishing, you know, tearing up entire ecosystems with our trawls, we were chasing fewer and fewer fish further and further out to sea. And most of the fish I was catching was going to McDonald's for the fish sandwich, which is a sandwich I still love and sneak away to eat regularly. But don't tell the foodies that. And I love that job, so even though we were destroying ecosystems, you know, just the humility of being in 40 foot seas, that sense of solidarity of being in the belly of a boat, working with other folks, and that sense of meaning of helping feed my country. But then the cod stocks crashed back in Newfoundland and that was a real wake up call for a whole generation of us. And it's what taught me that not protecting ecosystems is not an environmental issue. It's not about birds and bees and bears. It's about jobs. It's about kitchen table issues like, there will be no jobs on a dead ocean. And that's when I kind of joined the environmental movement in a certain way. And, you know, the, our journey now into climate change is the same thing. There'll be no jobs on a dead planet, there'll be no food on a dead planet. So, I remade myself as an early ocean farmer, growing salmon. And that was supposed to be the answer to overfishing, right, and job creation, we're going to feed the planet. Instead, it was just, you know, essentially pig farms out at sea polluting local waterways, growing really neither fish nor food. And what aquaculture did that point was trying to grow around existing markets. So grow what people want to eat. So people want to eat salmon, they want to eat tuna, that's what they grow. And I got disillusioned and then kept searching and I ended up here in Long Island Sound and remade myself as an oysterman. But it was just the beginning of early boutique, sort of specialty oyster companies emerging, and I was right outside New York. So I built a business around that. And then Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy came in and destroyed my farm two years in a row. And so suddenly, I found myself like on the front edge, a canary in the coal mine of the climate crisis that arrived essentially 100 years earlier than we were expecting. So that was a, you know, a depressing time for two years in a row and seeing this as a new normal, but it forced me to adapt, you know, and I think some of the best creativity, and this gives me hope in the era of climate change, comes when humans are in crisis, right. And that's really where we are. So I just took from the oyster that question of, you know, what should we be growing in the ocean and learned that there were thousands of edible plants, hundreds of kind of shellfish we could grow. And that was the beginning of my journey.

Brendan Smith is founder of GreenWave and author of Eat Like a Fish. (Photo: GreenWave)

MALLOY: So in your book, you include some recipes, which are pretty great. They looked really tasty, and I'm kind of excited, I want to try some. Where did you find these recipes? Did you come up with them, like, where'd they come from?

SMITH: Yes. So, uh, we worked with a lot of chefs over the years and what's been interesting is I started by working with seafood chefs. And it turns out seafood chefs were not the right folks to figure out what to do with sea vegetables. They kept on like baking seaweed salads or wrapping them around fish. And then I discovered this other sector, which people that specialize in making vegetables unhealthy. And I think Brooks Headley out of New York, who's a former pastry chef and a punk rock drummer, and that now run Superiority Burger and he's figured out how to make vegetables absolutely delicious and not worry about the health, so I gave him the kelp and he immediately made kelp noodles, barbecue kelp noodles with parsnips and breadcrumbs. It's just brilliant, right? The heat of the barbecue sauce, that softness of the parsnips, the crunch of the breadcrumbs, and it just completely de-sushifies seaweeds and you know people eat it and they just, they don't even think seaweed. So, and another chef we work with who has recipes is Dave Santos, who's an incredible Portuguese chef in New York. And just luckily, we're at this incredible moment of, sort of, American culinary experimentation. But it's hard to change tastes right? It's slow, and we don't really have time to bank everything on just changing tastes. So our other strategy is to make the seaweeds the soy of the sea but not evil, right, soy is extremely problematic. We all know the story about deforestation, things like that. We don't have that trouble with seaweed. But the soy industry did something fascinating in the 50s. They sat down and said, Okay, we're never going to get Americans to eat soy. So we'll put it in everything. And look at any label, whether it's like furniture to food, you're going to find soy in there. It's just woven through all the industries, so, we can take our seaweeds and do the same thing because seaweed’s an incredible fertilizer that's been used for a 100 years, can be used as animal feed: If you feed cows a 2% diet of asparagopsis, you'll get a 58% reduction in methane output. And this delicious tasting meat and milk and, stunning, we can use it for bioplastics. So the London Marathon just had seaweed water bottles.

MALLOY: Wow.

SMITH: So imagine that we've got this plastic crisis in the ocean. It's killing our oceans as farmers we could actually grow crops that we can turn into packaging like, this gives me hope. And if we do this right and we grow these crops, we can just weave it through so many different industries and create jobs don't have to wait just for changing taste.

MALLOY: Yeah. So your farm serves as a new ecosystem for so many different species that are living in these waters, as well as a community space. Can you talk about that?

SMITH: I mean, it's designed to be a community space, we don't own those waters. What we own is the right to grow shellfish and seaweeds. Anybody can come boat, swim, fish on the farm. And it turns out that if you start farming all these species together and do a polyculture system, you're recreating, you're just mimicking Mother Nature, which then attracts all these different species, whether it's, you know, ducks or seals or striped bass or crabs. It becomes this living ecosystem. As a farmer, you then just become a steward of this area. And so we can mix both revival of the ecosystem creating the shoreline parks that people can enjoy, while also saving and protecting these community spaces. I mean, think of these as underwater community gardens.

Brendan Smith (left), Living on Earth's Elizabeth Malloy (center), Jill Pegnataro (right) farm manager and hatchery technician. (Photo: Paloma Beltran)

MALLOY: That's amazing. So how did you really start becoming an advocate against climate change? And, are you seeing this becoming more of a common thing in the fishing community?

SMITH: So, I became active in the climate movement, not out of choice, it was because my job was directly impacted. You know, my farm was wiped out by Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy. Climate change was supposed to be this slow lobster boil that happened over 100 years instead, it's here and now. So I don't have a choice, right? I didn't come to this as an environmentalist. I came to this with the perspective that there are going to be no jobs, no food on a dead, like, that I have a stake in this. And I think the new climate movement isn't just about environmentalists, it's people from all walks of life that are being impacted by this, this crisis and all of us coming together to figure out solutions. One of the first things we did was we took our boat down to the Climate March in New York, took a group of shell fishermen, fishermen down there, and I was amazed that you know, we enjoyed the people doing urban gardening in Detroit, we joined the coal miners who were trying to solarize the haulers, you know, and I just felt the first time like, this is my community.

MALLOY: It's really interesting that you say that, that felt like a real community for you. I mean, I think climate change has done so many things. But one of the things it's really done is brought so many people from different walks of life together to figure out different ways to survive and move forward to thrive.

SMITH: I think of it as the politics of Yes, right. Where we're all coming together around solutions like environmentalists traditionally have been the politics of No, you stop pipelines, you know, you stop hog farms, and that's the politics of No, it needs to be done. Right. But we now need a politics of Yes, of what are we going to build? What are we going to do? It's not about waiting for other people to do this and for us to decide, you know, is it good or bad? It's like, let's build a future we want. What's exciting on the ocean is that it's kind of a blank slate. Like we can actually do food right, do agriculture the right way. Take all the lessons of industrial agriculture, all the lessons of industrial aquaculture, and not make the same mistakes, right? We can weave justice into the DNA of this new economy. Make sure, you know, young beginning farmers, indigenous folks, women all have access to this new economy, we can make sure our seed isn't privatized. Make sure people do polyculture not monoculture. I mean, I think that's the exciting thing. Like we can actually build a new economy from the ground up and do it in the right way. And that's, you know, there's a lot of potential there.

MALLOY: Yeah. It's incredible. So, you saw some pretty crazy things as a commercial fisherman, and this is somewhat of a calmer lifestyle now so how are you adjusting to that.

SMITH: Yeah. I mean, it was rough, right. I mean, you know, I can't go to the same bars I used to and I now get beat up. What am I going to be like? Yeah, I was out today. And I pulled up this amazing piece of kelp. Like, I gotta hang out with arugula farmers and drink tea or something, right. This was not the path for me, right. I'm a hunter, I'm a, you know, I have that sort of last generation of folks that hunt the earth for food, but I've had to say goodbye to it, and I really had to rewire my nervous system, but over time I've, I've really learned to love it. It is amazing feeling to lift a wall of plants out of the ocean, right and this sort of the shimmering, sort of deep brown colors, it really has, has changed me. I do miss being a fisherman. I miss that sort of adventure of the high seas, the thrill of chasing fish around the globe, but I still get to die on my boat one day. Like, that's the measure, like, I'm out here on the Mookie, and I'll be able to say goodbye to the world. As I sink into the ocean. I think that that'll be enough for me.

Related links:

- The GreenWave Official Website

- Ideas.Ted | “Vertical ocean farms that can feed us and help our seas”

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal, “Fishing Blues”]

Remembering EPA Head William Ruckelshaus

William Ruckelshaus swearing in as the first Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Seen from left to right: President Richard M. Nixon, William Ruckelshaus, Jill Ruckelshaus (wife), Chief Justice Warren Burger. (Photo: Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Only one person has ever served as an Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under two Presidents, and that’s William D. Ruckelshaus, who died the day before Thanksgiving. William Ruckelshaus was in fact the first EPA Administrator, appointed by President Nixon in 1970, and in addition to laying the foundation for the agency and defining its mission, he oversaw the implementation of the Clean Air Act in 1970. Soon after he was tapped to run the FBI as acting director and then named deputy Attorney General. He was also fired by President Nixon during “Saturday Night Massacre” for refusing to dismiss the Watergate special prosecutor, Archibald Cox. Back in 2010 we spoke with William Ruckelshaus about his career and his reflections on how the EPA had its origins in Earth Day activism that put pressure on President Nixon to protect the environment.

RUCKELSHAUS: To centralize that enforcement and regulatory responsibility at the national level made it much more difficult for industry to escape reasonable rules guiding their emissions into the air and water by running to a safe haven—to some state that did not as strictly enforce the standards. So, I felt that we had to initially show the American people we were serious about this by strictly—not only setting the standards—but strictly enforcing them to let people know that we meant business.

CURWOOD: Now, you come back for a second bite of the apple of the EPA when you become administrator again—what, it’s 1983, it’s during the Reagan administration. Tell me, why did you come back and what changed for you in terms of your sense of the agency’s mission?

William D. Ruckelshaus served as EPA Administrator from 1970 to 1973, and again from 1983 to 1985. (Photo: FBI, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

RUCKELSHAUS: I came back because the agency was in trouble and Burford who had been appointed by President Reagan had gotten herself in a whole lot of trouble, as did other appointees. They sort of bought the line that often is taken by Republicans in the administration that a lot of this social regulation—regulation to protect health, safety, and the environment—is an overreaction and the result of a sort of nanny state. She got in a lot of trouble as a result and president Reagan asked me to come back and help straighten the agency out.

CURWOOD: Now, wait a second—you’re a Republican.

RUCKELSHAUS: Right, well, I guess I still am. Barely.

CURWOOD: I believe you did support Barack Obama for president.

RUCKELSHAUS: Yeah, that’s right. I haven’t changed my mind all that much in the last 40 years, but the Republican Party certainly has moved. What I think the Republican Party has done recently is sort of give up on the environment. They rarely talk about it. I don’t think many of the candidates, or even their constituents think about it that often. And I think that’s a shame because these problems, many of them are real and need to be addressed in an aggressive way, or we’ll get in real trouble.

CURWOOD: William Ruckelshaus, the first and fifth Administrator of the EPA, who died November 27th at the age of 87. He will be missed.

Related links:

- Listen to the full interview with EPA Administrators William Ruckelshaus and Lisa Jackson

- E&E News “William Ruckelshaus, twice EPA chief, dies”

- NYTimes | “William Ruckelshaus, Who Quit in ‘Saturday Night Massacre,’ Dies at 87”

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut - Gymnopédie No. 1]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth