January 3, 2020

Air Date: January 3, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Rollbacks of 2019

View the page for this story

2019 saw the rollbacks of more than 80 environmental rules under the Trump Administration. Critics say these changes could harm more than the climate: they'll llkely hurt business, the environment, and human health as well. Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and professor at Vermont Law School, joins Host Steve Curwood for an overview of some of the key regulatory rollbacks. (12:13)

The Best Science and Nature Writing

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

The best science writing strives to entertain and educate in equal measures, and to help make the jargon of the scientific world accessible to the general public. To cover some of the most captivating recent science writing Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill spoke with Sy Montgomery, a bestselling author and the guest editor for the 2019 edition of The Best American Science and Nature Writing. (17:22)

Endangered Species Success Stories

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

2019 brought both good news and bad news for endangered species. While the Trump Administration finalized changes to the Endangered Species Act that could slow species’ recovery, several endangered species have bounced back thanks to the ESA, and a few others just received much-needed protections. Tierra Curry of the Center for Biological Diversity tells Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering about the mostly good news for endangered species in the U.S. that 2019 brought. (12:11)

Barren-Ground Caribou

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender, recounts a visit to the Arctic during a summer season and describes how climate change has led to melting snow and ice there, creating challenges for the caribou. (04:50)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tierra Curry, Sy Montgomery, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

This week we’re taking a look ahead at 2020 and back at some 2019 federal rollbacks of rules, including some for clean water protection.

PARENTEAU: The EPA under Administrator Wheeler has said we’re not basing the decision on science. We’re basing the decision on, quote, “policy” and we think we need to give more deference to the states who don’t want federal regulation of the waters.

CURWOOD: Also, we’ll hear about some of the best science and nature writing from 2019.

MONTGOMERY: In this world in which sometimes you just want to take a cyanide pill because it seems like everything is falling to pieces, a story like this just warms your heart and makes you realize science is our way out of the mess we've created.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Rollbacks of 2019

California has received 50 different waivers under the Clean Air Act since the rule was established in 1970. The rollback under the Trump Administration is the first time one of these waivers has been revoked. (Photo: Cindy Shebley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

During 2019 the Trump Administration rolled back or began to roll back more than 80 environmental rules, according to research by the law schools at NYU, Columbia and Harvard. And experts say these changes will harm the climate, the land, and human health. We don’t have enough time to cover all 80 plus rollbacks, but we asked former EPA regional counsel and Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau to help us understand just a few of the most broad-reaching ones. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve, good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, we're here to talk a bit about the regulatory situation when it comes to environmental protection and almost all the moves rolled back protections. So, let's walk through some of these. What about the waiver that California has had under the Clean Air Act, pretty much since it was passed back in the 70s. It seems that the Trump administration wants to take that away. Why and what's the impact?

PARENTEAU: So, California has actually received 50 different waivers over the history of the Clean Air Act from 1970 on and never has a waiver that's been granted ever been revoked. So once again, the Trump administration is setting a precedent. In this case, of course, the wrong precedent. And California had adopted a rule that required a certain number of electric vehicles and low-emission vehicles in their fleet. And then other states are able to join with California's standards for fuel efficiency and emission reduction. And 13 other states have done so. And all of those states are now challenging the Trump administration's revocation of what we call the California waiver. It is probably the single most important rule for reducing greenhouse gas emissions on the books. It's a major, major reduction of pollution, not just carbon pollution, but other forms of pollution. And of course, it's promoting the new generation of vehicles that we're going to see increasingly. And that's in litigation, and the wisdom of the legal academy is that the Trump administration is probably going to lose that argument because the Clean Air Act does not authorize revocation of California waivers. Only Congress could do that. And there's very little indication that Congress would do that. So, we'll probably see in 2020, a decision from the courts on whether or not the revocation of the California waiver is going to be upheld, and the betting, as I say is, it won't be.

CURWOOD: One of the most recent of these rollbacks concerns the Waters of the United States or WOTUS Policy. Please give me a bit of this history and what's happening with it now.

Wetlands serve as important habitat and provide ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, water storage and water purification. With the rollbacks under the Waters of the United States, or WOTUS, policy, wetlands and other American waters are at risk. (Photo: LivingLandscapeArchitecture, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Right. So, this is the rule that determines the scope of coverage of Waters of the United States. This includes rivers and lakes, wetlands, estuaries, and the rule has to do with where is the line between federal protection for these waters and waters that don't have that protection and they're left to the wishes of the individual states. The Trump administration has proposed a rule to roll back that jurisdiction to eliminate something along the order of 20% of the rivers across the country and over half of the wetlands that were formerly protected. If the waters are not covered by the Clean Water Act, then discharges to them are not regulated, including toxic discharges in some cases. Over 45% of the waters in the United States are impaired, meaning they don't meet water quality standards. So, we have a lot of work to do to clean up those waters. And one way to do that is to require permits for sources that discharge directly into the waters. It has wildlife benefits, fisheries benefits, public health benefits. And without that floor of federal protection, you get a crazy quilt of places where there is protection and places where there isn't protection. A lot of the pushback against the former regulations came from the Farm Bureau and the large agricultural industries. Also from the National Association of Homebuilders, the American Mining Congress. So, these are all the industries and land uses that cause water quality impairment, and they resent having a strong federal law dictating what they need to do to clean up.

CURWOOD: So in June, Pat, the EPA finalized what they call the Affordable Clean Energy rule to replace the Clean Power Plan from the Obama administration. Remind us about this rule and how it differs from the Clean Power Plan, and to what extent is it actually being enforced?

The Trump Administration’s Affordable Clean Energy, or ACE, rule focuses on minor adjustments to fossil fuel plants, rather than looking to the development of clean energy sources, as with the Clean Power Plan. (Photo: David Seibold, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Right. So the Clean Power Plan developed by EPA, under the Obama administration had targeted a reduction of greenhouse gases 32% by 2030. And in fact, we're well on our way towards achieving that goal. The Clean Power Plan tried to give the states flexibility in how to meet these emission reduction targets through things like using cleaner natural gas over coal, bringing on wind and solar and other renewables. The Affordable Clean Energy rule abandons all of that, and basically says the only thing we're going to do is try to slightly improve the efficiency of individual power plants. Some analyses say that might have a very small, negligible reduction in emissions. Other analyses say that the emissions might actually increase. But in any case, a lot of the emissions that are not greenhouse gas emissions, but are other pollutants, those kinds of pollutants will actually increase under the Affordable Clean Energy rule at a very high cost. So, some of the economic analyses of the ACE rule show that in fact, the benefits from the rule will be outstripped by the costs of the rule, which is more than a little ironic coming from an administration that's supposed to be saving money and improving efficiency and so forth. But these were campaign promises that the President made that he was going to repeal these rules and free the fossil fuel industry from these restrictions because the administration doesn't accept the science of climate, doesn't believe it's a serious problem. This is completely against what the science is saying, what the economics is saying. We're moving in exactly the wrong direction on energy policy right now.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about human health. Of course, enhancing climate disruption is bad for human health, but what are the rollbacks that stand out to you particularly as egregious when it comes to the lack of protection for human health?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, there are a couple that come to mind. One is this problem with disposal of coal ash from all of the coal mining in Appalachia and the use of coal in burning and generating electricity. So we have all across the country, these major lagoons full of this toxic coal ash. Once again, the Obama administration was beginning to address this legacy of the coal era and trying to clean up these pits, which are contaminating groundwater. So that's a health issue, because it has groundwater contamination components. And there was the famous case of chlorpyrifos pesticide. The Obama administration had proposed to ban this pesticide because of its adverse health effects. The Trump administration has renewed its use. And the Ninth Circuit ruled that the repeal of the ban on chlorpyrifos was illegal. So that's also tied up in a lot of litigation.

CURWOOD: Pat, there's this saying: if you have the facts on your side, you argue them. If you have the procedure on your side, you’ll argue that. If you have neither, you just kind of pound your fist on the table. To what extent are these rollbacks based on facts, regulatory procedure, or just simply pounding that fist on the table?

The September 2018 coal ash spill in Sutton, North Carolina. The Obama Administration had begun cleaning up legacy coal ash pits, but this process has been halted by the Trump Administration. (Photo: Jo-Anne McArthur, Waterkeeper Alliance Inc., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: The situation with the rollback of the Clean Water Act is a good example. The EPA, under Administrator Wheeler has said we're not basing the decision on science. We're basing the decision on, quote, “policy”. And we think we need to give more deference to the states who don't want federal regulation of these waters. And the problem with that, of course, is that there are spillover effects. If one state decides not to protect its waters, that has impacts on other states that depend on the same waters, rivers and lakes and so forth. So, that's a clear example of an administration saying facts don't matter.

CURWOOD: And what you've been describing, Pat, sounds pretty dire in the eyes of folks who care about environmental protection. I'm sitting down though, so you can tell me. What do you think that 2020 has now in store for environmental regulations under this administration?

PARENTEAU: Well, more of the same. I don't see any major change in philosophy or approach. We were looking for maybe some improvements in at least those egregious public health problems from Superfund sites. But here we have the Trump administration arguing in the Supreme Court, that property owners around Superfund sites should not be able to go to state court to get additional remedies when the Superfund remedy that EPA has adopted won't protect their property or their groundwater or their health. We hoped that we would see something in response to the Flint water crisis on protecting public water supplies. Haven't seen as much on that as we were promised. There could be a lot more done with strengthening the rules under the Safe Drinking Water Act. EPA's capability of enforcement has been reduced through budget reductions and staff that's been leaving because they're simply demoralized. They don't feel like the agency is on mission anymore. So, some of the areas where I'd like to be able to say we've seen a little bit of progress, it's really hard to find them.

CURWOOD: So, if there's a new administration following the 2020 elections, what might happen then, in your view?

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

PARENTEAU: A lot of these issues can be repaired and reversed. This is one of the reasons why some of the industry, including industry within the electricity industry and the automotive industry, don't actually agree with everything the Trump administration is doing. There's a real split in the industry about having policies that go back and forth dramatically from one administration to the next. Businesses want more predictability, more consistency, more of a level playing field. And what we're going to see with a new administration, I think, is a reversal of many of the issues that we've been talking about, which of course, will simply mean more and more litigation. That might make some of us that are in the business of producing environmental lawyers happy, but I don't think it's in the national interest. So, hopefully with the new administration, we can begin to repair some of the damage that's been done by this administration, but do so in a way that's durable.

CURWOOD: Alright, to what extent is this all bad news from the perspective of environmental protection and conservation? What is there in the way of something positive that the Trump administration has done?

PARENTEAU: Well, I don't know about the Trump administration. But I can tell you that I think across the country in the states and cities, there's a lot of good things going on. We see more and more clean energy coming in to state portfolios with pledges to meet 100% renewables in California, in Hawaii, in New Mexico. Here in Vermont, we've got a pledge of 90%. There's a long way to go to achieve those. But I think the states are the ones that are moving on that. And cities more and more are doing the same thing with the way that they're purchasing clean energy, the way that they're greening their cities, adapting to climate change. So, I think the real good news is not anywhere at the federal level. It's all at the state and local level.

CURWOOD: So, how fair is it to say that Pat Parenteau, the former EPA Regional General Counsel and law professor, is glad to see 2019 in the rearview mirror when it comes to the federal level of environmental protection?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, goodbye and good riddance is the way I would term that. And let's hope for a much brighter future in 2020. Lots of big things happening in 2020. It will be an interesting time, whether that's a curse or a blessing, we'll find out.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Pat Parenteau is a professor at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much for taking the time with us and I hope you enjoyed the holidays.

PARENTEAU: My pleasure, happy holidays, Steve.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Trump to Revoke California’s Authority to Set Stricter Auto Emissions Rules”

- The New York Times | “95 Environmental Rules Being Rolled Back Under Trump”

- The Hill | “Misguided Affordable Clean Energy Rule Is on the Wrong Side of History”

- Inside Climate News | “Trump EPA Targets More Coal Ash Rules for Rollback. Water Pollution Rules, Too.”

- More about Pat Parenteau

[MUSIC: Peter Calo, “Red River Valley” on Cowboy Song, traditional American, Tune Stew (A division of North Star Music)]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A look at some of the best science and nature writing from 2019. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Scott Wilke, “Eu Vim da Bahia” on Brasil, by Gilberto Gil, Beach Music]

The Best Science and Nature Writing

Emi (mother, foreground) and Suci (baby, background), two of the Sumatran rhinos at the Cincinnati Zoo in 2006. (Photo: MrsApplegate, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

It takes special talent to write about science for the general public. Part of the challenge is translating the technical jargon of science into more accessible language. And trying to explain anything new is also hard, especially since it can come with complexity and uncertainty. Unless you are Sy Montgomery. She’s one of those science writers who makes you feel less like she is teaching you something and more like she’s sharing some exciting thing she’s discovered. Sy is a New York Times best-selling author and National Book award finalist who has written over 20 books about the natural world. Most recently she was the guest editor of the 2019 edition of The Best American Science and Nature Writing. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill caught up with Sy to discuss some of the best science and nature stories to come out of the last couple of years.

MONTGOMERY: Boy, there was a lot of good science journalism happening, which is kind of a miracle when you consider that science writing, in newspapers at least, there's just no space for it anymore. So, it's kind of a minor miracle that these kinds of stories, some of them, you know, investigative journalism that takes weeks, months to complete, is actually coming out. But it was hard deciding which were the best ones to include. And I was delighted that it was so difficult to make that choice.

O'NEILL: Let's start talking about some of these incredible, incredible pieces. A personal favorite of mine and a personal favorite of yours, if I remember correctly, has to do with Sumatran Rhinos, if you could tell us a little bit of that story.

MONTGOMERY: Well, who doesn't love a good Sumatran Rhino story? Sumatran Rhinos are the rarest of the rhinos, and rhinos are disappearing so rapidly from the earth. Of all the species, the Sumatran, the only one who's a hairy rhino, they have been under horrendous poaching pressure, and they're practically extinct in the wild. So, this is a fabulous success story called The Great Rhino U-Turn and it was written by Jeremy Hance for Mongabay. And it tells the story of how the species was rescued from extinction against all odds, thanks largely to Cincinnati Zoo. And the story goes like this. In 1995, there were only three Sumatran Rhinos in America in zoos, and they were the only ones remaining from 40 rhinos that had been captured in the wild to breed since 1984. 11 years after these 40 rhinos were captured, half of them had died. None of them had bred. So, by 1995, three were left. One was in New York. One was in Cincinnati. One was in California. So you're not gonna get a lot of breeding done that way. So, it was decided to bring the two female rhinos to Cincinnati. First, they had to find out, are the females even in condition to breed? So they trained the females to submit to ultrasounds, so you could look inside them and see how they were doing. They found out that one had a horrible growth in her uterus. She was never going to have a baby. They were down to one female and one male. And the female was named Emi and she wasn't ovulating. So, what are you going to do about that? Well, they took a big risk. They figured, you know, let's just put the two of them together. Now, why is this big risk? One ton rhinoceros meets another one ton rhinoceros. And what if they feel like I wouldn't mate with you if you were the last rhino in the world? Wait, you are the last rhino in the world! But I still don't want to mate with you. If they get into a fight, you have got two tons of big problems. And typically, they're very solitary animals, and they don't want to be together until the female is ovulating. They put two together. And sure enough, the male did in fact mount the female. Well, no baby resulted from that. She did have four pregnancies, but all those pregnancies were not successful. Then a fifth, and then the sixth one. You wait 16 months for a baby rhino. The infant is born. And his name was Andalas. And he was healthy. And she gave birth to two more. And the wonderful thing is they're no longer at Cincinnati Zoo. Everybody misses them. But where are they? They're in Sumatra, at a breeding center and perpetuating their race. And this was just against all odds, and just a wonderful story. And it shows you the individuality of the animals. I love the story because you got to kind of know the names of the animals and what their temperaments were like, and you got to know the big risk that people were taking. And when we take a risk to save a species, and it works, in this world in which sometimes you just want to take a cyanide pill, because it seems like everything is falling to pieces a story like this just warms your heart, and makes you realize, science is our way out of the mess we've created. And thank God, it's one of those inspiring, feel good stories, and it's one of my favorites in the whole book.

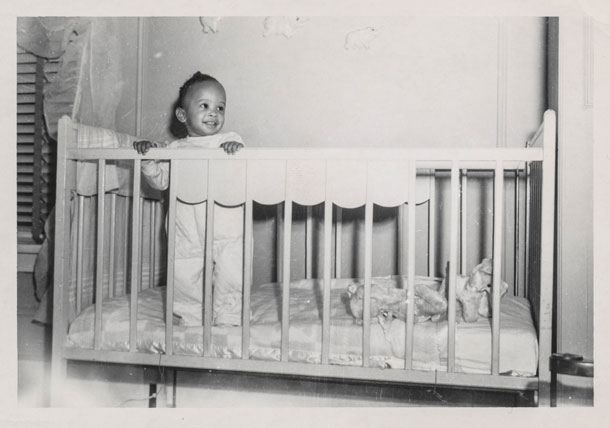

Black women are approximately four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white women. (Photo: NICHD, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O'NEILL: And now another one of the stories is again, to do with babies, but this time looking at humans and specifically, black women in the United States, what it is like for them. Could you share with us a little bit of that story?

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, wow, this blew me away. I couldn't believe it. It was one of those stories that you're reading it and just like oh my gosh, you can't believe it. The statistics blew me away. Started with statistics from 1850. Okay, slavery did not end until 1865. The white infant mortality rate was 217 per 1000 babies, the black infant mortality rate was worse, but not all that much worse, 340 per 1000, because babies just died all over the place. But then, between 1950 and the 1990s, babies of all races who died in the first year of life dropped 90%. Yay, this is awesome. In 1960, the US was ranked 12th in developed countries for infant mortality. But now, our country, the most developed arguably in the world, the richest country in the world is ranked 32 out of 35 and the US is one of only 13 countries in the world where maternal mortality got worse in the past 25 years. And what is driving that is the terrible death rate of black women and their babies. I was absolutely floored. Black infants in America are more than twice as likely to die as white infants. But what's even more shocking is that black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy related causes than white women. And you're like, why? Well, immediately you think income disparity, you know, poverty. These women, maybe they just don't have the education. They don't know something's wrong, they don't have enough money to get to the doctor. People have all kinds of problems related to poverty. And that's not even it. And that's what blew me away more than anything else. It's not related to income. It's not related to education. A black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education.

O'NEILL: That statistic floored me when I heard that the first time. It's just shocking to hear that.

MONTGOMERY: Well, this is why journalism like this is what we desperately need. Everybody would have decided, oh, it's poverty or oh, it's education. But no, it's not. So, people went to work trying to find out what was the deal here. So, there were all kinds of other things they investigated. Were black women drinking or smoking more? Of course, let's blame the woman, right? It turns out, they drink and smoke less during pregnancy than white women. So that wasn't it. But something about growing up black in America was doing it. Then they looked at other statistics about what happens to sick black people in our medical system in general. And I was absolutely shocked. Diabetic black people are more likely to have a foot or leg amputated than diabetic white people. What's that about? Black people are less likely to get adequate pain relief in the hospital than white people. What is going on here? They receive inadequate treatment because they're black. So, this whole story that starts out horrifying, just gets more horrific with each page. But that's how you change things. And Linda Villarosa is part of the change because she, in this article, has pointed out what is going wrong.

A young Black child in 1953. Infant mortality rates in the United States have gotten worse in the past few decades, due in large part to the high mortality rate of Black mothers and children. (Photo: SimpleInsomnia, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: One of the things that really is incredible about that is how that author, she pulls together all of these statistics and this data, and she also combines it with this beautiful piece of storytelling about this one woman whose pregnancies she follows.

MONTGOMERY: It made, it made it very visceral and very real.

O'NEILL: One of the things that they mention in the article is how much racist mindsets can factor into how black women and black people in general receive treatment in hospitals.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, that blew me away. There was one survey of doctors, and this, this is modern, this isn't like in the 1800s or anything, in which doctors said that they thought that black people were less sensitive to pain than white people. That's insane. That is crazy. And it makes me scared for all my black friends. And we never talk about stuff like that because my friends and I we talk about animals no matter what, but it scares me to death and you want to do something, but of course, you know, not even the doctors, if they have a bias you don't know you have a bias until someone points it out. So, thanks to this fantastic piece of investigative journalism, now we can make a change.

O'NEILL: A lot of the stories in this collection are stories of adventure, taking you everywhere from the deserts of Chile, to the Sea of Cortez to Cincinnati for those Sumatran rhinos, really examining what kind of science and what kind of scientific journalism can happen in these incredible places around the world. And one of the stories concerns a search for extraterrestrial life, but a search for extraterrestrial life on the planet Earth. Could you tell me a little bit about that story?

The Atacama Desert in Chile is home to a team of scientists’ quest to learn what extraterrestrial life might be like. (Photo: Alessandro Caproni, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, this was one of my favorites, too. In it, Rebecca Boyle takes us to the driest nonpolar desert on Earth. The Atacama Desert in Chile. So this is this totally alien spot on our own planet and she takes us there and why? Because it is the most like Mars of any surface on Earth. It's 90 degrees, if there was any shade -- there isn't -- with daytime gales; nighttime is perfectly still and from a distance, the place she went called the Salar Grande looks like this sea of pebbles. But you get up close and it resolves into a field of fissures and slabs called polygons and edged with these smooth round nodules, which are pure salt. Totally seems like another planet, but it's our planet. So this was once a salt flat. It dried up between two and 5 million years ago. The salt flat is at least 225 feet thick. And she gets to go to this utterly lifeless was looking place to look for life. And she finds it.

O'NEILL: It's incredible when you think about all these tiny microscopic critters that can exist, wherever you could possibly think of them on the highest mountains, in the depths of the ocean floor, in volcanoes and see events, all sorts of extremophiles who just cherish the most difficult place to live and they're still going to eke out an existence one way or another.

MONTGOMERY: It's amazing. And, like, Where is the life? Well, it's inside the salt nodules. She cracks them open with the scientists that she's accompanying. And inside, some of them are these little green stripes. And they're called halobacteria. And they are, they are alive! Life just loves to be anywhere, life seems so irrepressible. And for those of us who hope there is life elsewhere in the universe, this is thrilling. And it's this fabulous living laboratory. But what I love so much about what Rebecca Boyle does in this is she takes us to this place, we meet these cool people. And so she blends this adventure story with all the science. And she also quotes these wonderful Chilean poets. I mean, didn't you love that? I love that. There's some Raul Sarita and Gabrielle Mistral. And he would refer to the sun as Lord burn all things. And one of the quotes that she takes from this Chilean poet is one that I kind of feel like is emblematic for this whole, this whole book of fabulous science writing, and it's his exhortation, “lift up your face, child, and receive all things.” That's what science does for us.

O'NEILL: Wow, a stunning work of journalism. You're very right that that is very emblematic of all of these stories that you've put together. And I suppose now I have to ask, Who did you hope would read these stories and what do you hope people will take from them?

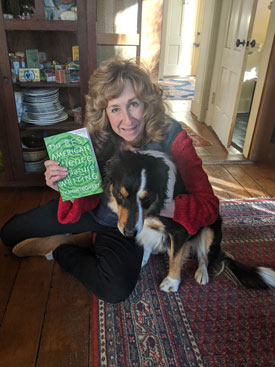

Sy Montgomery poses with The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2019 and her dog, Thurber. (Photo: Isaac Merson)

MONTGOMERY: Well, the lovely thing about every one of these stories is that I think anybody who likes to read anything, will enjoy them. Because they have such a fabulous wow factor. You know, you don't have to have any special training in science to enjoy these. And that's what great science writing does. It connects people with science and makes them care about and love science. What we do is bring to light the truths that we're finding in the world. We people have to have that knowledge, we have to have the truth in our hands, because our leaders aren't doing it for us. So we've got to take the lead. And we've got to make the change in leadership as well. In the introduction, I wrote about the Boston March for Science and I spoke at the kids’ March for Science, because as we've seen, children are not just the leaders of tomorrow, they are the leaders of today. And little kids were my audience. And I told them the story of a scientist that I'd worked with and went to Papua New Guinea with her. Her name was Dr. Lisa de Becque. And we climbed to 10,000 feet into this cloud forest. We're looking for tree kangaroos. We got radio collars on them, we got to find out where they went. We're in this cool place, I mean, cloaked with mist and burns and moss and these amazing animals that looked like Dr. Seuss had designed them. And all these kids were standing in the rain on this pouring freezing cold day, absolutely riveted to the story of Dr. Lisa de Becque and the science that she was doing good science writing is going to spark that interest in you. Whether you love science, whether you're 10 years old, whether you're ninety years old, it makes us excited about learning the truth of our world and makes us excited about the adventure of learning and the excitement of discovery. And that is part of what makes us human.

CURWOOD: Author Sy Montgomery speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Listen to our most recent book interview with Sy Montgomery, for How To Be A Good Creature

- Sy Montgomery’s Website

- The Best American Science and Nature Writing for 2019

[MUSIC: Sultans Of String, “Highlander 10 Speed” on Yalla Yalla! by Chris McKhool, FACTOR/Chris McKhool]

CURWOOD: Coming up – In search of caribou in the Arctic. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sultans Of String, “Highlander 10 Speed” on Yalla Yalla! by Chris McKhool, FACTOR/Chris McKhool]

Endangered Species Success Stories

Nene geese at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. The species is being downlisted from endangered to threatened thanks to successful recovery efforts. (Photo: Sean Hagen, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Endangered Species Act is credited with saving dozens of animals from the brink of extinction, though the Trump administration moved to weaken some rules under the act last year, which would make it harder to protect wildlife at risk. Despite that, there have been some positive developments when it comes to protecting endangered wildlife in 2019. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering asked Tierra Curry, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity to take a look back at 2019 in terms of wildlife conservation.

CURRY: Well, I'm hoping today we can focus on all the good news and ignore the bad news and make this a happy program. So a lot of not cool stuff happened with this administration and the Endangered Species Act this year. But there were quite a few success stories of species that their populations rebounded, protections were put in place for them and so much though, they're going to come off the list now. So that's great. One of those is a bird called the interior least tern. And it's the smallest tern species. It's black and white. And because it's in so many places, people have a good chance of seeing it. It ranges from the Dakotas down to Texas and over on the coasts. And it's a little bird that likes big rivers; it needs open sandbar habitat. And so, when we started doing flood control on the rivers and damming them and just manipulating the flows, a lot of the sandbars got drowned out and so the interior least turned declined. In 1985, there were less than 2,000 of them, but after it was protected under the Endangered Species Act now there's more than 18,000 of them. So that's a really happy success story. And it's proposed for delisting now.

DOERING: Wow. So I guess that means the Endangered Species Act can really work.

CURRY: It can, 99% of the species that are protected under the Act haven't gone extinct. And so getting on the act, although it's bad news that a plant or animal needs to be added to it, it's good news because it means it's actually going to get the protections it needs to recover. And so this, all of these de-listings bring the total number of species recovered under the Endangered Species Act up to 46. Which doesn't sound like that many. But if you think about it, by the time of species gets put on the list, it's declined so much that it's going to be difficult to recover the population. And it's only been a couple of decades since the Act was put into place. And so now we're seeing these protections that have had time to recover the populations. They did it and it worked and so species can come off the list now.

DOERING: What are some other animals that have been delisted this year?

CURRY: Another species that came off the list this year is the Kirtland’s warbler. It's a beautiful black and yellow bird lives in Michigan and Wisconsin and overwinters in the Bahamas. It was among the first species to be protected under the Act back in 1967. And by 1987, there were fewer than 200 singing males. But now there's more than 2,300 singing males. And this bird is a little bit weird in that it won't nest in trees that are more than 15 years old. And nobody knows why. But it just really likes this young habitat. And so when the land was wilder and there were glaciers moving here and there or fires burning here and there, there were always like young trees, but now they have to maintain, actively maintain, young habitat for it and also control cowbirds because cowbirds are these parasitic birds that lay their eggs in other birds’ nests. And then the Kirkland’s warblers were raising the cowbirds instead of their own nestlings. And so the Fish and Wildlife Service actively maintains their habitat, controls cowbirds and it allowed the Kirtland’s warbler to rebound and so it was delisted this year because it's recovered.

The Kirtland’s warbler is another Endangered Species Act success story. The little songbird no longer needs protection under the ESA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced in 2019. (Photo: Doug Greenberg, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Good news for the Kirtland’s warbler. Any other good news for species?

CURRY: Yes, there was a lot of good news for endangered species this year. The nene, which is the Hawaiian goose that has been downlisted from endangered or threatened. In the 1950s, there were fewer than 30 Hawaiian geese left because of hunting and because of introduced predators that were eating them and their babies because their ground nesting birds, so it was also protected in 1967, less than 30 birds left, and there's this great story in 1962 a Boy Scout troop hiked with these cardboard backpacks with 35 of these geese. They hiked 10 miles into Haleakala crater on Maui, because it was a safe habitat for them. And so that happened and then a lot of other restoration and predator control has happened for them and now there's 2,800 of them. So from 30 to 2,800, and they're being down listed to threatened this year.

DOERING: Wow. So these Boy Scouts hiked with cardboard boxes to go give them a safe nesting place for these nene Hawaiian goose.

CURRY: Yes. And I think that must have been so stressful. I'm so clumsy, I would have tripped and fallen in the crater. So I'm glad it wasn't me. I'm glad that they, they successfully carry these birds 10 miles over rocky ground to a fresh start.

DOERING: Wow, rocky volcanic terrain. That's amazing.

CURRY: It is amazing. And if people Google that, like, Hawaiian goose and Boy Scouts, there's these great old black and white pictures of them with their cardboard backpacks carrying the geese.

DOERING: Did we have any animals added to the list this year? And that means they'll get more protections?

CURRY: Yes, there were only three species added to the list this year, which is a bummer because there's certainly hundreds more species that need protection. But I guess it's good news when anything gets added under this administration. And so there's two stone flies in Glacier National Park. Stone flies are little insects, they need water. And so these particular ones live in glacier melt. And so the western glacier stone fly and the meltwater lednian stone fly were officially added to the Endangered Species Act. They're threatened by climate change. And the Glacier National Park is expected to lose its glaciers by 2030. And when the glaciers are gone, these stone flies are probably going to be gone as well. And so we petition for protection for them about a decade ago and they finally added to the list.

The interior least tern is one of the latest species to be proposed for Endangered Species delisting, given that it has bounced back to about 18,000 individuals, nearly ten times the species’ low point when it was protected as endangered in 1985. (Photo: USFWS Midwest Region, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Well, so I mean, are these flights going to be okay? Even if they do get the protections that could help them but then climate change is going to happen and you know, what's going to happen to them?

CURRY: Well, hopefully them being protected under the Endangered Species Act because they're solely threatened by climate change will raise more awareness of climate change and push this administration and individuals to do more, to fight for policies that will protect these flies and also the human, all the humans on the planet from the effects of climate change which are becoming more and more undeniable every day.

DOERING: It's with us everywhere we go. No matter where we turn.

CURRY: It really is, and to go back to the other species that was protected this year, only three species were protected by the US Fish and Wildlife Service this year. The other one is a really pretty little fish called barrens topminnow that lives in central Tennessee, and it's very blah looking most of the year but during the breeding season, the males turn these crazy bright green glittery colors; it would make a beautiful evening gown. It's like the prettiest iridescent green. And it was actually proposed for listing back in 1977, but didn't get protections till this year. And it used to live in 18 streams but now it only lives in five and a couple of them keep drying up and so scientists have gone to heroic lengths to protect this fish. They keep an eye on its springs and due to increasing drought, when they are going to dry up the scientists go out and collect them and take them into captivity and keep them there until the stream is flowing again. And then they take them back out. And so it would have been lost already if there weren't people who cared about it deeply and went out to protect it. And the Tennessee Aquarium Conservation Institute and this group called Conservation Fisheries, Inc, both have Ark populations of it now so that if it did go extinct in the wild, there would be populations living in captivity that they could take back out again. But hopefully now that it's officially listed, there'll be more funding for its recovery and some habitat protections will be put in place for it.

Two species of stoneflies, the western glacier stonefly (above) and the meltwater lednian stonefly, were added to the Endangered Species list in 2019. These flies live in Glacier National Park, where they rely on glacier melt, and as the park could lose its glaciers by 2030 they are expected to be severely impacted by climate change. (Photo: USFWS)

DOERING: Could you tell us about some of the changes that the Trump administration has made to the Endangered Species Act recently? What does that mean for wildlife?

CURRY: So this year, the Trump administration finalized what they call improvements to the Endangered Species Act. One of them: before this year threatened species received the same protections as endangered species, and now threatened species don't receive any protections at all unless a special rule is written for them. And so, like, the Pacific fisher was proposed to be listed as threatened. But its special rule exempts logging. And logging is one of the primary threats to its survival. And so it is a case where the Trump administration improvements to the Endangered Species Act are going to keep the Pacific fisher from getting any on the ground protection from logging unless we can convince them that it should be listed as endangered or that it should have a 4(d) rule that actually protects its habitat. Another change they made is, for when a species gets protected under the Endangered Species Act, it's supposed to get critical habitat for its protection. And the Trump administration has said that for species that are threatened by climate change, they're not going to designate critical habitat for them. And so that is, of course, ridiculous, because, you know, one in three species on Earth is currently threatened by climate change. And that's basically just codifying saying, Hey, we're not gonna do anything about this problem.

The colorful Barrens topminnow was given ESA protection in 2019. This little fish was proposed for listing all the way back in 1977 and has survived thanks in part to nongovernmental conservation efforts. (Photo: Emily Granstaff, USFWS)

DOERING: So Tierra, we've talked about some of the things that happened for endangered species in 2019. What do you think could be coming up around the corner in 2020?

CURRY: So this year, two big reports came out, one of them from the UN saying that a million species are at risk of extinction. And then a report came out from the International Union for Conservation of Nature last week, saying that one in four species that they assessed are threatened. And so the number of species that are threatened with extinction just continues to grow. And so we need more public awareness of the extinction crisis. We need all of the presidential candidates to be talking about the climate emergency and the extinction crisis. And then we need to rebuild the Endangered Species Act, and we need to fund it. Like we have this tool that can fight extinction in the Endangered Species Act, and it's been consistently underfunded. So it needs a lot more funding, so that we as a country can look around, find all the imperiled species, protect them and figure out how to protect their natural heritage, and I think that protecting these, the species and the habitat they need will also go far and protecting us from the worst impacts of climate change.

DOERING: Yeah, say more about that. Why is there a link between protecting species and ecosystems and, you know, mitigating climate effects?

The Trump Administration finalized changes to the Endangered Species Act in 2019, one of which removes some protections for threatened species like the Pacific fisher. (Photo: USFS Region 5, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURRY: Well, species need habitat and to fight climate change, scientists have found that like forest and grasslands and wetlands and carbon storage, the soil is like a place where instead of us trying to figure out how to burn coal and then pump those emissions back into the ground, if we just protected intact habitat, that has a huge buffering effect for greenhouse gas emissions, and it will protect the animals that live there. So like national parks and national wildlife refuges, create more of them put stronger protections in place for our national forest and the public lands that we already have. There's been this huge push under the Trump administration to develop fossil fuels on our public lands. And, you know, we and a lot of other groups started this Keep It In the Ground campaign when Obama was president, saying, no more fossil fuel leases on federal lands. And at first was criticized as a crazy idea, like Hillary Clinton herself said this is a crazy idea. Like we're not going to do that. And now all of the candidates are talking about ending fossil fuel leases on federal lands. So that's been a big ground shift that's happened fairly rapidly. And we absolutely need to do that; we need to keep fossil fuels in the ground on federal lands and doing that will protect habitat for tons of endangered species as well.

CURWOOD: That’s Tierra Curry, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- About the recovery and delisting of the interior least tern

- About the recovery and delisting of Kirtland’s warbler

- The nene, Hawaii’s state bird, has been downlisted to threatened following recovery

- About the western glacier stonefly, listed as endangered in 2019

- About the meltwater lednian stonefly, also listed as endangered in 2019

- The Barrens topminnow has also been listed as endangered

- About the Endangered Species Act rollback

- Trump Administration statement on its Endangered Species Act updates

[MUSIC: Scott Wilke, “Noturna” on Brasil, by Ivan Lins, Beach Music]

Barren-Ground Caribou

Caribou running in the Arctic Snow. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Well, the holidays are wrapping up and Santa’s reindeer, or caribou, can take a break from the imaginations of children for another year. But Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, recently travelled to the Arctic to see herds of caribou on the move during the Arctic summer. He found climate change has led to melting snow and ice there, creating challenges for the caribou.

LENDER: Tundra by twilight is a thing of awe. And terror. It neither starts nor ends. White. Flat. Except for the piles of cobbles huge and strange and dark, each a flattened sphere fifty kilos and more, implicit of the immutable will that ground them into shape and carried them here and formed these standing barrows. Beautiful but not inviting. Nothing out here is inviting. The absence of night. The wind that comes in waves, and waves; snow corrugated into blue shadows and bright crests.

Picture of a female caribou. Caribou are the only deer in which males and females both have antlers. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Lying low is not shelter.

There is no shelter.

We left first camp very early. The travel has been long and difficult. We cannot go any further. Tents are pitched for the night. We start to prepare something to eat, and meanwhile, melt ice for tea and stand around warming our hands on the cups. A wolf trots by. He is young. Unhurried and unwise he only glances at us, to him a passing curiosity. The Inuit do more than glance. Their eyes lock onto him. If they were not guiding us, if we were not here, they would shoot him.

“Have to,” Paul Pemik says, “or they’d kill off the caribou.”

I ask, “What happened before you were here to kill them?”

He thinks about that. “I don’t know. I guess they killed each other,” he says.

We see no more wolves.

The wind never stops.

I am too tired to sleep.

The very next morning there are caribou. Pemik, and Jason Curley, one kneeling one standing, are the first to spot them. Some shimmer of movement; a fine discontinuity in the texture of the horizon; only an eye trained from childhood would see it.

Caribou are migratory therefore very sensitive to changes in the landscape. Climate change plays a role by warming the Arctic ice and incrementing diseases and parasites which can kill off herds. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

We wait.

The caribou come up over the rise and into the narrow glacier-cut valley in single file. A small contingent of twenty, twenty-five at most, cows and their young of the previous year. The Inuit call them “scouts” because they precede the main migration and they are never shot. If they were harmed, the great moving mass of the Qamanirjuaq herd would be – somehow – informed. And turn away. And that would be the end of it because the hunters would never find them.

We don’t find them anyway.

Despite that a spotter plane went out ahead of us and gave this precise location. Despite all the ingrained history of caribou an Inuk hunter knows: where they cross lakes, ford rivers and streams, the likely routes between the piled stone barrows. It has been this way the last couple of years. Cold and miserable as it is, it is not cold enough. The komatik has been bouncing over patches of rock - jamming your knee joints if you don’t keep your muscles sprung, half knocking your teeth out if you don’t keep your mouth clamped shut - rock that should be under four feet of snow pack. But there is more to it than that. We have done more to the Arctic than warm it. It is not just the warmth to which the caribou object.

Caribou has been an essential part of the subsistence of the Inuit tribe. Caribou meat is high in protein, and caribou skin has been used to make art and clothing. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The scouts, who have been watching us for a while (more wise than that lone wolf) break into a gallop. Though there is no leader or obvious leadership they hold to single file as they run. Then they slow and turn back. They are closer now, but not close. Not as close as they would have been had the Qamanirjuaq materialized, the bucks with their enormous antlers, all of them plodding in a near-trance and their wide camel-like hooves lifting, falling; the clicking of their ankles from which they take their Inuit name: Tuktu!

Instead of here, where they were supposed to be, 200,000 caribou came through three hundred kilometers away.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender. For pictures, check out the living on earth website, LOE dot org.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: YoYo Ma, “Dona Nobis Pacem” on Songs of Joy & Peace, Traditional, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Special thanks to Destination wildlife. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play-

And if you have a smart speaker, just ask it to play the Living on Earth podcast. And like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth