November 27, 2020

Air Date: November 27, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Climate & Georgia Senate Showdown

View the page for this story

The Georgia runoff elections in January will determine which party controls the US Senate, and thus the scope of climate legislation during the Biden Administration. James Bruggers, a reporter at InsideClimate News, speaks with Steve Curwood about where the candidates stand on climate and the environment. (05:29)

Mustering Georgia's Environmental Voters

View the page for this story

The 2020 Presidential election had a historic turnout, including young voters and voters of color, who are statistically more likely than other voters to list climate or the environment as their top priority when voting. Nathaniel Stinnett, Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project explains to Steve Curwood how turnout of environmentally-focused voters might influence Georgia's twin US Senate run-off elections January 5th. (09:16)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Weekend Editor Peter Dykstra joins Steve Curwood to discuss a major solar energy project in Texas, the biggest to date in the U.S. They also cover how the coronavirus pandemic has led to drastic funding cuts for public transportation in large cities including New York. From the history books they discuss the progress and shortcomings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, as it turns 32 years old this week. (04:06)

Making the Pill from Yams to Fish

/ Alison BruzekView the page for this story

Most formulas for the birth control pill use the synthetic hormones progestin and estrogen, derived from crude oil and even plants. Once these hormones make their way through a human body and into wastewater systems, they can affect fish and other animals in the environment. Alison Bruzek reports. (08:26)

The Dark

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

As night falls many animals rely on sound to find each other and communicate. In the dark, sound is sight. Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender tells of a nighttime chorus in southern Colorado. (03:25)

Note on Emerging Science: Sea Otters Protect Alaskan Reefs

/ Leah JabloView the page for this story

Sea otters are a textbook example of a keystone species: the health of the kelp forests they live among depends on these furry seafarers to keep kelp-eating sea urchins in check. New research shows that when sea otters aren’t around, sea urchins are even more destructive than previously known, tearing through the very reefs on which Alaskan kelp forests grow. Leah Jablo reports on the research and how it connects to climate change. (01:49)

Planetary Health

View the page for this story

A healthier planet also means a healthier society. That's the basis of a 2020 book drilling down on the intersection of environmental change and human health. Physician Sam Myers co-edited Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves with Howard Frumkin. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his book and to explain how saving the planet can also save human lives. (14:54)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: James Bruggers, Nathaniel Stinnett, Sam Myers

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Alison Bruzek, Mark Seth Lender, Leah Jablo

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A look at the role and demographics of environmental voters in Georgia’s upcoming Senate runoff elections.

STINNETT: It doesn't fit in neatly with the stereotype that I think most Americans carry in their heads. There's a lot of nuance there, but it's really important to understand this is not a wealthy white constituency anymore. This is a constituency made up of people of color and people who make less than $50,000 a year.

CURWOOD: Also, how yams, the humble root of modern birth control pills, helped make an affordable medicine taken by 150 million women.

SANTEN: The cost went down from $1,000 a gram to about $5 a gram. And quite honestly, without that, there would not have been the feasibility of developing a birth control pill.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Climate & Georgia Senate Showdown

Democratic challenger Jon Osoff supports a major infrastructure program that includes renewable energy, sustainability, and coastal community adaptation. (Photo: John Ramspott, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

With the announcement that John Kerry will be the special Presidential climate envoy for the Biden Administration, it’s clear America is headed back into climate action. Mr. Kerry is a former Secretary of State and one of the architects of the Paris Climate Agreement. And he will undoubtedly shepherd a host of executive orders and rules to advance climate action and reverse the anti-climate policies of the Trump administration. Scoring major gains will also depend on the US Senate, where the Republican majority has mostly blocked climate actions. But winning the two runoff elections in Georgia could give control of the Senate to the Democrats. Republican Senator David Perdue is looking for another six year term, and is facing Democratic challenger Jon Ossoff, an investigative journalist. Republican Kelly Loeffler was sworn in this year to temporarily fill Georgia’s other Senate seat, but to keep for the next two years she has to beat Reverend Raphael Warnock, a Democrat, and pastor at the same church once led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. James Bruggers writes for InsideClimate News and has been following these twin races and how environmental voters could tip the balance. James, welcome back to Living on Earth.

BRUGGERS: Thank you appreciate it.

CURWOOD: In terms of Georgia, where do the Democratic and Republican candidates stand on climate?

BRUGGERS: As a general rule, they're not really talking about climate a lot. But just like Democrats and Republicans across the country, the Republican candidates don't have much to say about it at all, and in fact, seemed to have a fossil fuel agenda. And they both very much support President Donald Trump. And the two Democratic challengers have built climate change into their platforms. So even though it may not be a top tier issue that they're talking about all the time, it's definitely something that you can find on their campaign websites. And it's something that you'll hear them talk about from time to time.

CURWOOD: Before the presidential election we spoke with Jim about the Ossoff Perdue race and how each candidate views climate and the environment.

Although Incumbent Senator Kelly Loeffler (R-GA) has not said much about climate change, she aligns herself with President Trump’s pro-fossil fuel agenda. (Photo: Office of Senator Kelly Loeffler, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BRUGGERS: Senator Perdue, who's a former CEO of Dollar General, he generally avoids climate conversations except to praise Trump for exiting the Paris Climate Agreement, for example. And he excoriated the Obama administration's Clean Power Plan, which Trump's administration has, you know, killed. And he also voted against a sense of the Senate resolution that climate change is real and caused by people. Ossoff is like a lot of other Democrats in that he's addressing climate change through this lens of jobs and the coronavirus, he says that Georgia needs to rebuild from the wreckage, as he calls it, caused by the coronavirus pandemic. He's not endorsed the Green New Deal, but he's called for a major infrastructure program that includes clean energy and energy efficiency and also kind of preparing Georgia coastal communities to adapt.

CURWOOD: Turning to the other race, I asked Jim to talk to us about the record of Republican Kelly Loeffler when it comes to environment and energy.

BRUGGERS: It was kind of hard to find out really, it's not something that she's campaigning on at all. And she's never held any public office before. And so you can't really check and see, you know, how she voted on something in the past like you can with incumbent politician. And she's only been there for a year. She was the CEO of a business that did trading in energy credits at some point, but her whole thing has been that she supported Donald Trump 100% of the time.

Senator David Perdue (R-GA) is one of the strongest supporters of President Trump’s pro-fossil fuel agenda. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Raphael Warnock is in favor of the Green New Deal, or not?

BRUGGERS: You know, neither of them, Warnock nor Ossoff, are campaigning on the Green New Deal. It's typical across the Southeast, what I saw Republicans were able to use the Green New Deal as a cudgel in many ways. And so what you'll find is they won't use that language. So Reverend Warnock, he will talk about how he's guided by his faith. He has described the Earth as the Lord's, he talks about how we must be stewards of the Earth that our children will inherit. He says rejoin the Paris Climate accords. He wants to reverse Trump's attacks on the EPA and environmental regulations. He talks about preparing Georgia's coastline for rising sea levels and the types of infrastructure investments that you need to do that adaptation. And he also believes that he wants to set goals for carbon reduction, and to have a clean energy economy by 2050. Many of the tenets that you'll find in the Green New Deal are there. It's just he doesn't describe it that way. He doesn't call it the Green New Deal.

CURWOOD: These two races are going to determine which party takes over the United States Senate. If the Democrats should happen to take both seats, they, with the vice presidency, presumably the Vice President Harris, they would have this very thin majority. So what are the stakes of control of the Senate in terms of the future of national climate legislation?

Democratic Senatorial candidate Reverend Raphael Warnock’s platform centers on climate and environmental justice. (Photo: Raphael Warnock, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BRUGGERS: Generally speaking, Mitch McConnell has not had a climate agenda. His agenda has been a pro-coal, pro-fossil fuel agenda. And the democrats now have a climate agenda. And President-Elect Biden has a $2 trillion climate plan that he wants to get through Congress. So if he doesn't have his party in control, he has very little chance of having his plan make it through Congress. And so that ultimately, is what this all boils down to. However, there is this rule that we all know about in the Senate where you've got to get 60 votes. So you know, it's likely that whatever we see is going to be compromised. And of course, if we have compromise legislation that actually might be more durable, so that might be a good thing.

CURWOOD: James Bruggers is a reporter at InsideClimate News, who covers the US southeast. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Jim.

BRUGGERS: Yeah, thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- InsideClimate News | “Senate 2020: The Loeffler-Warnock Senate Runoff in Georgia Offers Extreme Contrasts on Climate”

- InsideClimate News | “Senate 2020: In the Perdue-Ossoff Senate Runoff, Support for Fossil Fuels Is the Dividing Line”

- The New York Times | “What’s a Runoff, and Why Are There Two? Here’s Why Georgia Matters”

Mustering Georgia's Environmental Voters

An estimated 850,000 registered voters in Georgia consider climate or the environment to be their top priority when it comes to voting. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The November general election in Georgia was very close, and the two Senate seats will be decided in runoffs January 5th. So to see how environmental and climate voters might influence those races we called up Nathaniel Stinnett to crunch the numbers. He’s founder and executive director of Environmental Voter Project. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Nathaniel!

STINNETT: Thank you, Steve. It's so great to be back.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, please remind us how you determine who is and who isn't an environmental voter.

STINNETT: We actually have a pretty high bar for what it means to be an environmentalist. We're focusing on people who don't just care about climate or the environment, but they actually prioritize it as their number one issue over all others.

CURWOOD: All right, so we've talked before about the demographics of environmental voters, please remind our listeners about that, again.

STINNETT: It doesn't fit in neatly with the stereotype that I think most Americans carry in their heads. Environmentalists are more likely to be Black or Latino than white. They are more likely to make less than $50,000 a year, then more. They're certainly more likely to live in urban areas than in suburban or rural areas. And they're more likely to be young rather than old, although there's a lot of nuance there. But it's really important to understand this is not a wealthy, white constituency anymore. This is a constituency made up of people of color, and people who make less than $50,000 a year.

CURWOOD: What kind of estimate do you have of how many environmental voters there are in the United States?

STINNETT: There were a whole bunch of polls throughout 2020 that put that number anywhere between 10% and 12% of registered voters, which is a lot more than we saw in 2016, or even 2018. Now there are 211 million registered voters in the United States. So if 10% or 12% of them list climate or the environment as their top priority, well, that could be anywhere from 20 to 24 million registered voters. But as you and I know, Steve, just because you're a registered voter doesn't mean that you actually show up and cast a ballot. And that's where the rubber meets the road. And that's where our work at the Environmental Voter Project takes place.

CURWOOD: All right. So, among these environmental voters, folks who say that this is number one, and they're registered to vote, what percentage turn out for elections?

STINNETT: Well, the data is still out on the presidential election that we just had. What we do know is that in 2016, so the 2016 presidential election, only half of those registered environmentalists showed up to vote. But the good news is, we have reason to believe they turned out at a much higher rate in 2020. Because even though we don't have all the data, we do have data from early voting. And what we do know from early voting is that people who listed climate or the environment as their number one priority, were voting at a 15 percentage point higher rate than the general electorate in early voting.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about Georgia, now. What was the turnout for folks that you have identified as environmental voters in Georgia in the recent presidential election?

STINNETT: The Environmental Voter Project in Georgia was targeting over 200,000 environmentalists who had never, ever, ever voted before. So that's what we were targeting in the state of Georgia for the presidential election. And we know that 69,000 of them voted early. I want to reiterate, these are first time voters. They had never, ever voted before. And they cared so deeply about climate and the environment that it was their number one priority. And they showed up early. And so yeah, that's an incomplete picture. We don't know who did and didn't show up on Election Day. But by any objective measure, that's extraordinary. When you have almost 70,000 first-time voting environmentalists show up early? Yeah, they were fired up on November 3.

The Environmental Voter Project works to get already-registered voters who prioritize the environment to show up to the polls. (Photo: cyclotourist, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the ethnic composition, now in Georgia, looking ahead at this run off. I guess, historically, Nathaniel, Black voter turnout has been lower in runoffs compared to white voter turnout. How important is the Black vote in influencing the outcome of these two Senatorial runoff elections?

STINNETT: The Black vote is crucially important to the outcome of these two Senate elections. Crucially important. Because you're right, Georgia always sees a significant drop in turnout, when you go from a general election to a runoff. So as an example, let's just go back to the last big statewide runoff they had in Georgia, which was in 2018. In 2018, 3.9 million people voted in Georgia's general election, but only 1.47 million voted in the runoff. So 37% of the General's turnout. It was just a huge, huge drop. And yes, Steve, you're right. Black and Brown voters are a big part of that drop off, them staying on the sidelines. And so, this time around, there's no doubt in my mind that who decides to stay on the sidelines and who decides to vote again, will be everything. It will be everything to this election, because if you're Loeffler or Perdue or Ossoff or Warnock, any of the four candidates, you have no idea how many people are going to show up. You don't know if it's going to be 2.5 million, 3 million, 4 million. And that's a huge, huge spread.

CURWOOD: So, how important is the issue of the environment and climate change among Georgia's voters?

STINNETT: Yeah, so what we see in our research is that Georgia is almost right in line with the entire country, with the number or percentage of voters who list climate or the environment as their top issue. Our research shows that 11% of Georgians, so just one tick, one percentage point lower than the national average, have a really, really high likelihood of listing climate or the environment as their top priority. That's a significant percentage. And in real numbers, what that means is, there are about 850,000 climate-first and environment-first voters in Georgia who are registered. And so yeah, they could absolutely be a difference maker on January 5, but only if they show up.

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

CURWOOD: So, how do you persuade folks who you think aren't gonna show up, to show up?

STINNETT: Well, we use two different approaches. The first is we just educate them on all of these new easier ways that they can vote. Especially when you are an unlikely voter, someone who does not have a history of voting in elections, you might not know that you can vote early in person. You almost certainly do not know that you can go online and request a ballot be mailed to your house. So, one aspect of what we do is just educating them, making sure they understand that, actually, voting is a lot easier than you might think it is. And then the second step is because at the Environmental Voter Project, we aren't trying to change minds, we aren't trying to convince people to care more about these issues. We're just finding the ones who are already with us and trying to get them out the door and get them to vote. We have the luxury of our messaging being completely agnostic. I mean, all we care about is behavior change, Steve, so we could talk about chocolate chip cookies, if that was the best way to get these people to vote. And what we have found is the best way to change their behavior is to treat them as social beings rather than rational beings. We never tell these people, hey, you care about climate change, so it's really important for you to vote in this one election. And we don't try to rationally convince them of the value of their one vote in an election of millions. Instead, we use little, like, sort of peer pressure and social pressure messages. We'll say things like, hey, Steve, did you know last time there was an election, 73 people on your block of Main Street showed up to vote. Just teeny, little nudges like that, making them realize that they might miss out on something that all of their neighbors are doing. Another thing that we're doing is there are a whole bunch of environmentalists who we think are unlikely to vote on January 5, but they just voted in the presidential election. Because remember, turnout falls, turnout goes down in these runoffs. And so, what we've been doing is we've been sending thank you notes to these people who just voted, to positively reinforce their behavior. We're following up with them. And we're saying, hey, we know that you just voted for the first time in this presidential election. Congratulations. Preserve your good voting history. There's another election coming up on January 5.

CURWOOD: Well, let's see what happens. Nathaniel Stinnett is the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Nathaniel, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

STINNETT: It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Environmental Voter Project

- Listen to LOE’s previous interview with Nathaniel Stinnett

[MUSIC: The Infamous Stringdusters, “Truth and Love” on Rise Sun, by The Infamous Stringdusters, Tape Time Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up –using ears to “see” in the dark. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Project Trio, “BRB” on Instrumental, by Project Trio, self-published]

Beyond the Headlines

The Metropolitan Transit Authority, which runs New York City’s subway system, is asking for $12 billion in relief funding to deal with its $16.4B deficit. (Photo: Pom’, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

And on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter! What do you have to tell us about what's going on beyond the headlines today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve! We'll start out with a little big news from Texas. That tired old cliche about everything being big and bigger in Texas. But here's some good, big news from Texas on the clean energy front.

CURWOOD: Oh, what do you got?

DYKSTRA: The Samson project in northeastern Texas is a huge solar energy project, biggest to date in the United States, over a gigawatt of power. Another big part of that story is who has already committed to buying that solar power. You've got corporate entities like at&t to power their local operations, Honda, McDonald's, Google, Home Depot, and three moderate sized cities in the vicinity: Bryan, Texas near Texas A&M, Denton, Texas, and Garland, Texas.

CURWOOD: This is the biggest solar panel array we've seen Peter?

DYKSTRA: In this country. And of course, Texas is more than happy to claim the crown. But also we'll see if other states can take the crown or the 10 gallon hat back away from Texas.

Hoesung Lee is the current chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Photo: Jean Marc Ferré, UN Photo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, with the COVID-19 pandemic, many state and county and city governments have been stretched absolutely beyond the limits of their budgets. Some are looking at drastic cutbacks to mass transit. There was a recent study that took a look at big transit systems, including the biggest: New York City. New York is looking at potentially big cuts in bus and subway service. And that would be an economic disaster to New York, even bigger than the bite that COVID-19 has taken out of its economy.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I would imagine so, Peter. And there's serious talk, you're telling me of cutting back the budget of the subway system in other places, too?

DYKSTRA: Around the country buses and subways could be cut back. And the cruel irony in that is we've all seen how COVID-19 has had a bigger impact on poor communities, and I can't imagine the disparity of the impact on poor communities if bus and subway service went away.

CURWOOD: Let's take a look back at history now Peter, and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: Well, we're going to do another birthday this week. Last week, we celebrated the 82nd birthday of my old boss, Ted Turner. This week, the birthday is for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It turns 32. It's heading toward middle age. What we used to call climate change is now increasingly the climate crisis. There's some question about whether this 32 year old is having the full and desired effect we hoped it would have.

Samson Solar is set to start the largest solar PV project in the United States in Northeastern Texas. (Photo: Ricketyus, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, Peter, but think about it. The IPCC, those 1500 scientists that are part of it shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore. You know, that wasn't so bad for what at the time would have been, what a 19 year old?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, that's true. And to be fair, you got to bear in mind that those 1500 or so climate scientists are the cream of the crop of the scientific community. But here's maybe one silver lining: in this toxic cloud of COVID-19, is that it's brought to the fore the consequences of what happens when we avoid and ignore our scientists. Maybe the world will take the cue and pay better attention to what the climate scientists have now been saying for decades. And what we now see not as a future problem, but one that's right in our faces.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is an an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve! Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Bloomberg | “Severe Transit Cuts Would Cripple U.S. Economy, Experts Warn”

- Electrek | “Texas Will Host the Largest Solar Project in the US”

- For more on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[MUSIC: Along Came Betty, untitled, on Brad Melhdau’s Monogrammed Guest Towels, by Biff Smith, self-published]

Making the Pill from Yams to Fish

Birth control pills typically contain synthetic progestin and estrogen. (Photo: Sarah C, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Worldwide, more than 150 million women use birth control pills. Most use a version made of two synthetic hormones, progestin, and estrogen. The little pills come from a surprising source, and these hormones can also affect waste water. Reporter Alison Bruzek has the story.

BRUZEK: Step one in making a birth control pill: Find the right wild yams.

SANTEN: The brilliant move was to go down to Mexico and find all of these yams.

BRUZEK: This is Richard Santen, an endocrinologist at the University of Virginia. And he’s talking about the 1942 trip that gave us one of the pill’s key components. The traveler was chemist Russell Marker. And he wasn’t just a fan of tubers in general. He was hunting for a specific type of yam. Because Marker had discovered something huge in his lab at Penn State: you could modify compounds found in certain plants, and turn them into hormones. He’d already found he could take a molecule from the sarsaparilla plant and transform it into progesterone. And that’s due to a similar chemical structure. But the cost of that molecule was just too expensive. In Japan, chemists had found they could isolate a similarly shaped molecule from a yam.

SANTEN: So he went down to Mexico, he tested 100 different types of yam until he found the one that he wanted to use... the plant that contained the precursors of progesterone.

BRUZEK: That yam was growing near a stream, by a bus station in Veracruz. Scientific name: Dioscorea Mexicana. Also known as the tortoise plant, because of its shell-looking roots. Without a collecting permit, he brought back the root. Some say he bribed a local policeman to smuggle it out. Regardless, from that yam root, he created what was then the largest amount of progesterone ever produced.

Dioscorea Mexicana, the Mexican yam that chemist Russell Marker used to create synthetic progesterone in 1942. It’s also called the tortoise plant. (Photo: Rillke, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

SANTEN: The cost went down from $1,000 a gram to about $5 a gram. And quite honestly, without that, there would not have been the feasibility of developing a birth control pill.

BRUZEK: Progestin, or synthetic progesterone, is just one component of most pills today. They also contain estrogen. Much like progestins, human-made estrogen can be made from plants like soybeans, or yes, certain yams. Today, both hormones can also come from something else: fossilized carbon.

ANASTAS: To a first approximation, every pill comes from an oil rig.

BRUZEK: Paul Anastas is a chemist at the Yale School of Medicine.

ANASTAS: What that means is that the building blocks of most synthetic chemistry use petroleum and oil as their basis.

BRUZEK: Anastas says oil has the right chemical ingredients to be the foundation of all sorts of chemical compounds, including hormones.

ANASTAS: So most of the building blocks to build all of our materials — plastics, polymers, packaging, but even elegant materials such as pharmaceuticals — often came from petroleum, from oil.

BRUZEK: And that’s the beauty of chemistry. Take compounds from crude oil or a yam root, transform and tweak them in the lab, and there you have it: an astounding ability to create our own versions of progesterone and estrogen. And with just two molecules — these two hormones — you can make every rainbow-colored pill you see today.

[PACKET NOISE]

BRUZEK: Packed into their small, foil pouches. Punching the tiny pills out is surprisingly satisfying. You fill a glass of water. Take a drink. And … AHHHH.

[Pouring Water]

HARRINGTON: You swallow it

BRUZEK: Where it heads down the throat, into the stomach ...

HARRINGTON: It goes into your GI tract

BRUZEK: Where it gets absorbed through the intestinal lining ...

HARRINGTON: Actually gets absorbed into the circulation that goes straight to the liver and kind of passes through the liver metabolism.

BRUZEK: Elizabeth Harrington is a family planning specialist at the University of Washington. Once inside the body, the synthetic progesterone and estrogen do their thing — they inhibit other hormones that would otherwise stimulate the ovary to release an egg and trigger the rest of the menstrual cycle. In other words, they prevent pregnancy. And the body only needs a tiny amount of the hormones in the pill to get the message.

The bacteria in wastewater treatment plants are capable of reactivating synthetic hormones. (Photo: Kristian Bjornard, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

HARRINGTON: And the rest of it is hormonally inert byproducts.

BRUZEK: The liver actually inactivates the unused hormones. And those byproducts don’t hang around for long …

[FLUSH]

BRUZEK: Up to 68 percent of the hormones in each dose of a birth control pill are flushed away. The remains of your turkey sandwich, your lemonade, and those leftover hormones … all head down your apartment’s pipes, where they mix with the waste of your neighbors, flow out into the city sewers and, most of the time, wind up at your nearest wastewater treatment plant.

AGA: Most treatment plants, they rely on highly active microorganisms to biodegrade all the organic chemicals there.

BRUZEK: Diana Aga is a chemist at the University of Buffalo. And she’s saying: Good bacteria to the rescue. They degrade any contaminating or harmful things in the water like oil, dirt, household chemicals, and bad viruses and bacteria.

AGA: The purpose of wastewater treatment plants is really to remove nitrogen, phosphorus, dissolved organic carbons. So it’s not their goal to remove pharmaceuticals.

BRUZEK: Like hormones. In fact, sometimes, it’s actually because of the wastewater treatment plant that the estrogen from the birth control pills gets reactivated!

AGA: There are also these bacteria that are capable of deconjugating them again.

BRUZEK: Meaning the bacteria cleave off a key part of the chemical structure — restoring the active hormones.

AGA: So then they go back to the active form. And this active form are very persistent.

BRUZEK: So the hormones come out the other end of the wastewater treatment plant, arriving in wetlands, rivers, creeks — intact and active once again. Aga studies Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. And she’s seen the effects that estrogen, both human-made and natural, can have on aquatic animals, like fish.

AGA: Most of the fish will be affected as they swim. And sometimes we would see what we call feminization of fish. Where male fish starts developing eggs or sometimes a fish having both the male and female organs.

BRUZEK: Even though the amount of synthetic estrogen is small.

AGA: Like a teaspoon of salt, dumped into an Olympic-sized swimming pool. That’s how little it is.

A muskellunge or “muskie” fish examined by colleagues of Diana Aga for endocrine disruption. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Alicia Perez-Fuentetaja)

BRUZEK: Unlike humans who take the hormones in cyclical doses, fish are receiving that dose continuously from their environment. Now, before you switch from the pill to the patch — for the fish! — you should know — these effects aren’t entirely due to synthetic estrogen. The average amount in the pill has decreased significantly since it was first introduced — by as much as 20 times. And Aga says hormones that everybody — that’s women and men — make naturally are being rinsed into our waterways too. Even though the potency of synthetic estrogen is higher than what our bodies naturally produce, most estrogen in our wastewater is not from the pill.

AGA: Most of the endocrine disruption that we observe in the environment is because of the volume of natural hormones that humans excrete, and animals excrete, in particular.

BRUZEK: So you shouldn’t feel guilty every time you flush. But it does mean you shouldn’t rinse your extra birth control pills down the toilet, or pour them down the drain. You can bring extras to your clinic. Your local police department or the pharmacy in your grocery store may also have a drug takeback program. And while you’re there, head over to the produce aisle, and take a moment to appreciate the relatives of the yam that brought you the pill in the first place.

CURWOOD: Reporter Alison Bruzek.

Related links:

- About Russell Marker’s synthesis of progesterone from Mexican yams

- More about reporter Alison Bruzek of KUOW - Seattle

The Dark

The landscape of Monte Vista, Colorado. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: When night falls and animals can no longer see many instead rely on sound to find each other and communicate……. As Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender found in the mountains of Colorado.

LENDER: Two bald eagles come through the woods, a last shadow in the failing light. All afternoon, not far from here, eight of them perched in the same tree. They were waiting for the slough to thaw, to feed, upon the carp beneath the ice. The thaw never came. Now the eagles are headed home.

There is no moon… Moments later it is too dark to see.

[CRANE SOUNDS]

A flight of sandhill cranes crosses over, towards the shallow marsh where they will sleep, hidden between cattails coated and crystalline with frost. Their flight song and the woosh of their wings trails behind them, dimming as they speed.

[OWL SOUNDS]

The great horned owl sounds, a patina of deep strong notes which carry through the canopy to where his mate guards their nest. At a deserted farmhouse not far from here I’d seen another owl return at twilight. A dark shape.

[OWL SOUNDS]

The silent semaphore of his wings. He hooted. Then again.His mate would not answer. Because I was there. He flew away.

But now among aspens and oaks in this quiet and secluded place and with the safety of a moonless sky, this time the female replies, and the owls talk, back and forth, her voice thin, his low and smooth as butterscotch and rum.

[OWL SOUNDS]

Horses come through the gate. Branches snap as they mill among the trees. The great horned owls change place, the female gone off to hunt.

It begins to snow…

Sandhill cranes soar through the Colorado skies. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Beside these woods is a thicket, then furrowed fields sown with corn and wheat. Wild geese are bedded down there, and across the section fence, cattle.

A yelp. Then again from a different part. Short. Clipped - Coyotes, hunting. The farm dogs hear it too and bark. Indignant. Pretending. Though not chained they stay put.

[BULL SOUNDS]

Yip!

Yelp!

A high thin whistle like the bugling of an elk....

[BULL SOUNDS]

Now, all the coyotes know where everyone is and perhaps from that alone what they are about to do.

The geese call out.

[GEESE SOUNDS]

The bulls along the boundary line bellow loud and long and deep, Greek chorus in this vital play.

[BULL SOUNDS]

In the Dark, Sound is Sight.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Learn more about Mark Seth Lender's stories and adventures

- Read the Field Note for this essay

Note on Emerging Science: Sea Otters Protect Alaskan Reefs

In Alaskan kelp reefs, otter populations help to keep sea urchin populations in check. (Photo: Canopic, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Just ahead why protecting the health of our planet is crucial to protecting our own human health but first this note on emerging science from Leah Jablo.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

JABLO: New research published in the journal Science finds that sea urchins are destroying both carbon sequestering kelp and the coral bedrock beneath it, showing us how small animals can pack a big ecological punch.

[OTTER SOUNDS]

Animals like sea otters. The relationship between sea otters eat sea urchins is well known. A keystone species, sea otters eat sea urchins and keep their populations in check. But the population of sea otters has been in decline since the maritime fur trade of the seventeen and eighteen hundreds. Sea otters were hunted to near extinction and the population has never fully replenished- leaving the sea urchin population largely unchecked. They’ve already eaten through many Alaskan kelp forests, one of the world’s great carbon sinks.

But new research finds that urchins are now tearing through more than just the kelp forests. With few otters around to eat them, sea urchins are now eating away at what lies beneath the kelp: coral-like limestone reefs made up of red algae.

These luminous, bright-red, rocky reefs that lie on the Alaskan seafloor form the very foundation of its kelp forest ecosystem, and like much life in the ocean they’re also threatened by ocean acidification. Acidic conditions are making it harder for the reef algae to calcify, and form its protective limestone skeleton which deters sea urchins.

Ecologists say that the survival of these Alaskan reefs and the kelp forests above them all depends on the return of their furry keystone predators.

[OTTER SOUNDS]

In a small way, bringing back sea otters may help slow the warming of our planet, and help restore the ocean ecosystems they’re a vital part of.

CURWOOD: That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Leah Jablo.

Related link:

Read more on otter research at the Bigelow Lab of Ocean Sciences

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Network Music Ensemble, “We Gather Together” on Jazz Hymns, by Adriaen Valerius/Eduard Kremser, Network Music]

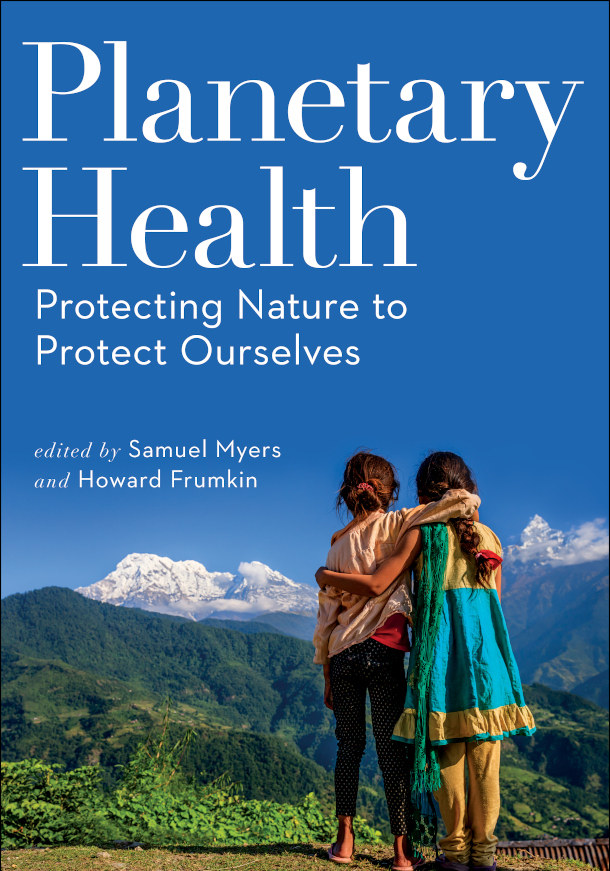

Planetary Health

Planetary Health delves into the intersection of environmental change and human health. (Image: Courtesy of Island Press)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

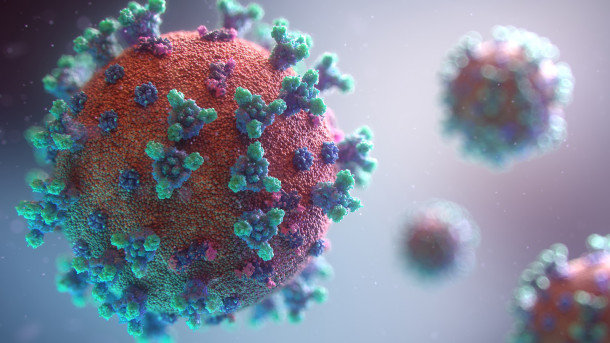

Human health is an integral part of any discussion about our changing planet and with the pandemic, it is more relevant than ever. Scientists say that our impacts on the environment increase the risk of pandemics. Deforestation, for example, brings us closer to animals that might have zoonotic diseases like Covid 19. And our agricultural system relies on large livestock farms that could serve as reservoirs for viruses. Physician Sam Myers studies the intersection of environmental change and human health. As part of our LOE Book Club live event series, I spoke to him about his new book Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves, co-edited with Dr. Howard Frumkin. Sam is the director of the Planetary Health Alliance and also a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health.

Welcome to Living on Earth, Sam!

MYERS: It's such a pleasure to be here with you, Steve. Thank you.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So Sam, the book we're talking about, it's named Planetary Health. This is the name of a brand new field of study and consideration that you've been involved with since the very beginning. So please tell me, what is planetary health? And how did you get involved in this field?

MYERS: Yeah, well, so you're right. Planetary health is a very new, very interdisciplinary field that I think has really emerged out of this moment that we globally find ourselves in. And it's a field that's focused on understanding the human health implications of our own disruption and transformation of most of our planet's natural systems. So it's about how global environmental changes actually come back to threaten our own health and well being.

Environmental change can impact the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19, but also non-infectious diseases like diabetes. (Photo: Trinity Care Foundation, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I suppose if biologist E. O. Wilson were with us at this moment, he'd say, well, what do you expect we we all evolved from this particular ecosystem? And you would say?

MYERS: Yeah, I would say that we've evolved over four million years in close conjunction with a set of actually relatively stable biophysical conditions and that now we are changing those biophysical conditions really across the board at the fastest rates in the history of our species. And so it isn't that surprising that those biophysical changes are translating into some pretty significant threats for human health across just about every dimension of health.

CURWOOD: So now, let's zoom in for a moment to one of the sections of this book. And I have to say you have many, many fascinating, interesting sections. And, it's a shame that we don't have five or six hours to go through everything that you have in this. But let's look at one section. You have a chapter on mental health on a changing planet. For a lot of people, this isn't such an obvious topic. But please tell us why you and Howie Frumkin thought this was important to include.

MYERS: Yeah, I think that mental health is one of the, you know, really understudied and under emphasized, but maybe one of the most important areas where accelerating environmental change is threatening our health. And, you know, there's a very large sort of well established body of evidence around the mental health effects of big disasters, we know that these fires across the West Coast are going to have an enormous mental health toll. We know that the big hurricanes have, you know, huge mental health effects in terms of depression, anxiety, job loss suicidality, and we know that those impacts are actually very robust and long lasting. So if you go back to Katrina victims, 10 years, 15 years later, you're still seeing mental health effects in those populations. But there's this whole realm of much more subtle mental health effects that people are starting to call eco anxiety or ecological grief. And, you know, it sort of begs the question, what is the burden that we carry with us of knowing that our own actions collectively are sort of systematically dismantling natural systems? What's the mental health burden people experienced when we learned that about two thirds of the mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fishes that used to inhabit the planet have been pushed off the planet by our own, you know, activities, and there's a whole area of research now starting to try to understand what those burdens are that may be almost invisible, but could still be very significant.

CURWOOD: So Doctor, I know you're very early in this process, but what treatments have you come across that are going to help with this intense pressure on our mental health?

MYERS: We talk about that very specifically in the mental health chapter that, you know, collective action, movement, building, social organizing, coming together to take action is not only necessary, it's also therapeutic. You know, Chris Jordan, who is a producer and an artist and did this amazing film Albatross about the challenge of plastics in our oceans, talks about how grief is the other side of love. And I think that's true. I think that if we love something, and it's in distress, then we grieve for it. And so I think the first step is to acknowledge that things are really challenging and that it's extraordinary that almost every single person in this country right now tonight, as we speak, is experiencing in some form or another some kind of ecological associated threat. But then we need to move from acknowledging the grief to coming together to take collective action. And I think that's why some of the movement building that's been going on over the last couple of years is so exciting. Whether we're talking about, you know, the climate strike movement and Greta Thunberg, or we're talking about the Extinction Rebellion, or we're talking about the birth strike movement, or, you know, any number of other kinds of social movements that not only are they the only way to address big power problems, where people actually have to hold governments and industries accountable to take the right actions, but they also bring us together, which is itself a therapy, I think, against the kind of ecological despair that I'm talking about.

Carbon dioxide has been shown to affect the levels of iron, zinc and protein in staple food crops. (Photo: Ellenm1, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sam, let's talk about another section of your book. And this, of course, actually a couple of sections on disease. In one section, you detail infectious diseases, I'm thinking of malaria, along with non infectious diseases: cancer, diabetes, heart disease. Tell us please about the correlation between environmental change and the risk of disease.

MYERS: Well, it's a huge topic, it's really kind of the first half of our book. And, you know, it's people tend to gravitate in their heads toward infectious diseases, we think about the hot zone, we obviously are all thinking about COVID now. We think about Ebola. And certainly, all kinds of biophysical change is associated with big changes in infectious disease exposures. But in a lot of ways, it's the non infectious diseases that are likely to drive the largest global burdens of disease. And so yeah, for example, the non communicable diseases. A big report came out a couple of years ago about global pollution of air, water and soil, showing that about 9 million excess deaths a year are attributable to pollution. And those deaths are non communicable diseases, their heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, some kinds of cancers, you know, the mental health effects that we just talked about, you know, and then there's this huge category of nutritional diseases, which is where I do a lot of my own research, where we're seeing biophysical changes associated with changes not only in the quantity of food that we can produce, but also even the quality.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Sam, let's drill down, in fact, on some of the research that you're doing on nutrition, it's now a number of years ago that we first noticed here on Living on Earth, the work that you were doing, showing that as carbon dioxide levels went up that this was bad news for a number of commodity crops. So talk in some detail about your research here in this area of nutrition during these times, please.

MYERS: So I wear two hats, I direct the Planetary Health Alliance, and then I'm also a research scientist. And so with my research, I'm engaged in a bunch of research projects, and most of which really look at how changing biophysical conditions affect nutritional outcomes around the world. And so one example is the work you were talking about where with a team of people all over the world, we're looking at this question of how rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere might affect the nutritional quality of staple food crops that we depend on for our nutrients. And what we found a while ago was that when you grow crops at carbon dioxide levels that we expect to reach by the middle of this century, they lose a lot of their iron and zinc and protein, really essential nutrients for human health. And so we spent several years after that initial finding, then modeling the diet of populations in 152 countries around the world to understand how these nutrient changes would actually alter the total sort of intake of those nutrients for people around the world. And whether it would push them into deficiencies of those nutrients, which are very serious public health problems. And what we found was on the order of 150 to 200 million people would be likely to be pushed into new risk of deficiencies like zinc and protein as well as you know, the billion or so people who already aren't getting enough those nutrients in their diets. And so that's just one small example of how, in a way that was almost impossible to anticipate, which is another theme in Planetary Health, right? These surprises and these unintended consequences, but who would have thought if we were sitting around 20 years ago, having a beer that, you know, adding carbon dioxide would make our food less nutritious. But, you know, that's one impact of adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, and yet it potentially affects hundreds of millions of people.

Sam Myers is the director of the Planetary Health Alliance and a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: Sam Myers)

CURWOOD: So what about solutions? Then let's just drill down for a moment on the question of solutions in this food and nutrition area. What things do you want to point to?

MYERS: Well, I mean, I think there are you know, there are solutions that we could point to around these specific questions like CO2, but that's really a tiny little piece of the big picture, you know, big picture is that our food system is probably more responsible for our transformation of the global environment than anything else. We use 40% of the terrestrial land surface for crop lands and pasture about half the accessible freshwater mostly to irrigate our crops, we're fishing out, you know, 90% of monitored fisheries so that there's a huge ecological footprint to our food system. And then the flip side is that environmental change is creating these enormous headwinds in producing food right when we need to roughly double food production in order to keep up with demand. And so we have this sort of, eye of a needle that we have to thread between destroying the biosphere by expanding agricultural production and still feeding 10 billion people. And, you know, that's where the, we really need to think about solutions. And we're starting to see that we're seeing you know, precision agriculture really taking off in the use of robotics to be much more efficient in how we use agricultural inputs, we're seeing new things like impossible burger or protein fermentation, the production of synthetic milk, or eggs that actually has a much, much, much smaller ecological footprint and is presumably considerably healthier for us to consume. Ther’e all of these innovations that are taking place, they're also our old tried and true methods from agro ecology, that are being shown through research to be much more effective, you know, more profitable with much lower ecological footprints. So when you start to look at this whole sort of huge menu of solutions that can be drawn from and you see similar things across energy systems and urban design. That's what I mean about this sort of rich terrain of solutions.

CURWOOD: So we just need the willingness, huh Sam?

MYERS: So I really think it's a matter of political will, yeah.

CURWOOD: I mean, I think probably an interesting example is bacon. I think many people will see bacon is, you know, really not very healthy. And yet, if you put it out, especially around the campfire, it'll disappear in a moment. How do we change?

MYERS: Well, I think we are changing. I mean, I think that the COVID pandemic has taught us that we're capable of actually changing in profound ways very quickly, which we didn't even know about ourselves. I think we have to start by the diagnosis, we have to start by recognizing that we're in really an extraordinary moment in human history. It's an inflection point, we cannot continue on our current trajectory, you know, our global house is on fire. And so we have to, we have to be motivated by the fact that we can't stay on this course. And then I think it's more than policy. I think it's it's more than what governments can do. I think that ultimately people and this goes back to your question about mental health, people need to come together to take collective action to organize and to hold their governments, you know, accountable and insist that stimulus packages are spent, you know, towards Green New Deals or, you know, other kinds of investments in infrastructure that could, that's going to take us in the right direction. At the end of the day, I think, you know, there's a spiritual sort of cultural dimension to this, we need to tell ourselves some different kinds of stories about our relationship to nature. And, you know, underlying all of these sort of ecological and public health crises, there's, I think, a spiritual crisis, where we've kind of lost our way and we've lost our sense of connectedness to the natural world.

Solastalgia describes the emotional distress caused by environmental change. (Photo: pandrii000, PxHere, Public Domain)

And I think we need to move from stories of sort of exploitation and dominance, which underlies so much of our action to stories of, you know, regeneration and reciprocity and codependence with natural systems. And so, you know, there's a role for our artists and our spiritual leaders in kind of getting us back on track on that level as well.

CURWOOD: Again, Sam, thanks so much for taking the time and congratulations for two years of hard work that I think people are going to use for many years going forward as a resource.

MYERS: Thank you, Steve. It's a great pleasure to be with you, I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- More on Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves

- More on Sam Myers

- LOE’s previous coverage with Sam Myers on how CO2 affects nutrients in food

[MUSIC: The Four Seasons, Autumn, 1st mvt, A.Vivald]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks to editor Ari Daniel, sound designer Ian Coss and the National Science Foundation for our story about the birth control pill. Also special thanks to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth