January 7, 2022

Air Date: January 7, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Winter Wildfires in a Changing Climate

View the page for this story

Nearly 60 million homes in America are within a mile of a wildfire zone, but most people are unaware of the risks. This risk was brought home in the suburbs of Boulder, Colorado on December 30, 2021 when the Marshall fire torched close to a thousand homes. Residents were shocked and surprised they only had a few minutes to evacuate. Colorado is no stranger to forest fires during summer and early fall but due to a megadrought and hundred mile an hour winds the Marshall fire burned through grasslands and into suburban neighborhoods. Fire expert and Director of Earth Lab at the University of Colorado, Boulder Jennifer Balch speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the Marshall fire and how climate change is leading to more fires year-round in many more neighborhoods than before and things residents at risk can do to reduce the danger of losing their homes to wildfires. (12:35)

Note On Emerging Science: Polar Bears Use Tools to Hunt Walruses

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

With large tusks and weighing over 2,000 pounds, walruses are a formidable foe for Arctic wildlife. But as Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports, polar bears are utilizing tools such as ice blocks or large stones to hunt walruses as access to other food sources for the bears declines. (01:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss an oil and gas project in a region adjacent to the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve that could threaten polar bears and the planet. Also, some good news for the planet as France bans many kinds of plastic packaging for fresh produce. And they take a look back in history to President Eisenhower’s 1955 proposal of the Interstate Highway System. (04:50)

Remembering Naturalist E.O. Wilson

View the page for this story

E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy, two of the world’s leading naturalists, passed away at the end of December 2021. White House Deputy Director for Climate and Environment Jane Lubchenco worked with both for five decades and joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about their contributions to conservation biology and their gifts for communicating the urgent need to save life on Earth. They reminisce about E. O. Wilson’s infectious love of the ants he studied and his big ideas about how to stem species extinction. (11:10)

Remembering Naturalist Tom Lovejoy

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and White House Deputy Director for Climate and Environment, Jane Lubchenco, continue their conversation about the legacies of leading naturalists E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy. They discuss how ecologist Tom Lovejoy brought people together to help protect the planet, from the Amazon rainforest to a cabin on the outskirts of Washington, D.C. (10:31)

A Call to Climate Action from Desmond Tutu

View the page for this story

Another champion of the environment who passed away at the end of 2021 was Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa. Archbishop Tutu was a leading non-violent opponent to South Africa’s rigid system of racial segregation known as apartheid and gave a call to action on the climate emergency as nations gathered in Copenhagen in 2009. (03:10)

Adiós Al Color

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender shares his encounter with a herd of elk galloping over the cliffs in Colorado's Great Sand Dunes National Park. (01:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220107 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Balch, Jane Lubchenco

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Climate change and the unusual winter fire in Colorado that burned through suburbs.

BALCH: I think for me talking about a winter wildfire this is climate change in my face. You know I do wonder as a fire scientist and I've talked about warming related disasters before, how many do we need before we are proactive?

CURWOOD: Also, remembering biologists Tom Lovejoy and E.O. Wilson who specialized in the tiniest of creatures.

LUBCHENCO: Being in his lab, with his students, seeing these just extensive colonies of ants all over his lab, he would just light up and get so excited talking about his ants and new big ideas. He was, he was just like a little kid in a candy shop! He was just so over the top excited and it was infectious.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Winter Wildfires in a Changing Climate

Smoke from the Marshall Fire is seen over a highway in Colorado. (Photo: Jack, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Nearly 60 million homes in the US sit less than a mile from a wildfire zone, but most people are unaware of the risk until it happens to them or people in their neighborhood. That risk was laid bare in the suburbs of Boulder, Colorado on December 30th when some 30,000 people had just minutes to evacuate as a wildfire ripped through their neighborhoods and torched close to a thousand homes. Fire season in Colorado is typically during the hot dry months of summer and early fall, with blazes most often in the forested wilderness but hundred mile an hour winds drove the Marshall fire in from grass lands. Big fires are increasing in the region, thanks to a megadrought linked to climate change. Fire expert Jennifer Balch lives in Boulder County and directs the Earth Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder. Welcome to Living on Earth Jennifer!

BALCH: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Well, first, how are you doing?

BALCH: It's been an exhausting and scary couple of days for us in Boulder and Louisville in Superior. You know I have, I have friends colleagues who lost their homes. And being a fire scientist, it's it's one thing to study it, but it's another thing to be living through it. And this event started just a couple miles from my home. And I know that, you know, it could have been could have been my home, it could have been my neighborhood. We're living with the reality of being in the wildland urban interface, where homes mingle with flammable vegetation, and this is our reality.

CURWOOD: To what extent did you ever think this could happen to you living there in Colorado?

From our photog @dave_wille near the Flatirons. These fires continue to take out entire neighborhoods. @CBSDenver #MarshallFire pic.twitter.com/UMViz2reI6

— Ryan Greene ???? (@RyanCBS4) December 31, 2021

BALCH: You know, I think about it quite a lot given this is the work that I do, and I study fires for a living but it's definitely a risk we're, we're taking on. I think one of the surprises with the fire that happened just in last couple days is that the this wildland urban interface is way bigger than we thought it was. There are a lot of homes at risk and I've done some of that work to show what the extent of risk is. We know that in the last couple of decades, there were a million homes within wildfire boundaries. There were another 59 million that were within a kilometer of those wildfires. And I think we just haven't been acknowledging the high level of risk that we're living with today and that risk is made worse by climate change and that's a big part of the story as well.

CURWOOD: And by the way, what do you mean by wildfire boundary?

BALCH: I mean, the the extent of the perimeter of wildfires. So we looked at essentially all the wildfires that happened over the last two decades and we have maps of them and and their extent, essentially the outer limits of where those fires burned to. And so within those burned areas, there were a million homes that were touched in some way, not necessarily burned to the ground, but we're within the boundary of those areas.

CURWOOD: And did I hear correctly that there may be what fifty-nine, sixty million homes that are very close to such boundaries?

BALCH: That's right. So another, you know, a million were within the perimeter of fires and the burned landscapes but another 59 million, we're not that far away within a kilometer. How did we get here? It's such a good question. You know, Colorado is is a beautiful state but it's also a very flammable state. Because it's a beautiful landscape there's a lot of people who want to live here and we continue to develop into flammable places without really thinking about what risk we're taking on. And I think there's a lot of room for us to do it better, to build better and to build more fire resilient homes and neighborhoods into our flammable but beautiful landscapes.

Colorado just experienced its most destructive wildfire in state history on... December 30th. The extreme fire weather behavior and rate of spread in a densely populated area in December is unprecedented and just hard to comprehend. #MarshallFire pic.twitter.com/q9JJ2VG2Kn

— US StormWatch (@US_Stormwatch) December 31, 2021

CURWOOD: So as I understand it, Colorado was abnormally warm this winter. Why is that? And in your view what influence does the climate weather have on the gravity of what happened in the Marshall fire?

BALCH: Yeah, it's a huge factor and fire's a great integrator, you need three ingredients for a wildfire to happen. You need it to be warm, you need fuels to burn and you need an ignition or spark. And leading up to December the end of December when this event started on December 30. We had the warmest June through December period on record for the Front Range going back to the 1960s. So what that did was it essentially made our fuels very dry and crispy and essentially ready to ignite. So it was a huge factor that played into what happened. And the fact that I'm even talking to you and talking about winter wildfires, is somewhat remarkable. And there's only been one other time in my career where I've talked about snow putting out wildfires, that's this year and last year. And so what we're seeing is consistent with a trend in warming that we know is influencing wildfires and making them more frequent and making them bigger. We've seen a two degree Fahrenheit increase across the west over the last century, we know that it takes just a little bit of warming to lead to a lot more burning. We've seen a doubling of the forests that have burned across the West since the 1980s.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you to put on your academic hat for a moment. What's the role of fire in the Earth system overall? I mean, more specifically, how does fire contribute to what's going on with climate warming and and how does this climate warming promote fire?

7 SMFR Engines worked overnight at the #MarshallFire and returned to the district safely this morning. 5 Engines and fresh crews returned this morning to assist, along with many neighboring fire crews. pic.twitter.com/qasiGfXTxZ

— South Metro Fire Rescue (@SouthMetroPIO) December 31, 2021

BALCH: So what fire does is it's essentially fast respiration. It takes all that carbon that's stored in plants and it pumps it back into the atmosphere. Combustion is the reverse equation of photosynthesis, essentially. So what you have happening very quickly is that carbon goes right back into the atmosphere through combustion. So fire itself has an important feedback to the atmosphere and into warming itself if that fire is out of whack with what the historical rate of returns have been and what the historical rate of re-accumulation of that carbon and ecosystems.

CURWOOD: So how fair is it to infer from what you said that with more and more wildfires, it's going to add to more and more climate disruption, more and more climatic warming,

BALCH: It will, particularly if you get vegetation change or transitions to other type of vegetation. So if we go from some forest systems to grassland systems that are more adapted to frequent fire, we're going to see a loss of carbon storage by those trees in those forest systems. And that is definitely a potential and we're seeing some early signs of transitions in that, across the West we have forests that are not recovering or not regenerating because little seedlings, the trees that come in after a fire are not surviving from year to year in the drought conditions that we're experiencing today. Now we had a very, we're in the midst of a very strong drought, despite the fact that we got this snowfall and it's, it's a mega drought, it's essentially more than 20 year period where we've had a lack of moisture contributing to it being very hard for plants to survive, particularly ones that need a little bit more water, like trees.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, I have to ask you about the summer fire season. I mean, what a winter fires mean for the well, historically, the more prominent summer fire seasons that we see in the West?

BALCH: So to me what this means seeing a winter fire means that we have a fire season, that's not a season anymore, it's an all year thing. And you know, that's going to stress out our firefighters our fire suppression teams in our communities knowing that we're gonna have to be aware of how dry it is throughout the year. And for the moisture conditions, we're not out of the deficit, the moisture deficit yet. We had a very good snowfall that followed that windstorm that propelled that fire forward, we got anywhere from five to 10 inches along the front range but usually this area sees about 30 inches of snowfall by this period of time. So I'm hoping we're gonna see more moisture in the next several weeks and months. And if we don't, what that means is we're going to have an early fire season again next summer, which sets us up for more burning and greater risk to communities.

CURWOOD: So what and where are some of the most vulnerable communities in the United States, now to wildfires? You know, which ones are most at risk? And what if anything can be done?

BALCH: I think, importantly we need to figure out who's most vulnerable. There's 13 million socially vulnerable Americans right now living with high wildfire risk. And I would guess that that many of them don't know that they're living with that risk. You know, I think part of what is a lesson from the marshal fire is that the wildland urban interface where homes are at risk is way bigger than we thought it was. And we need to help communities prepare and recover from these types of events. And there are things, there are important factors that play into whether a community is ready, whether it's a low income community, whether it has resources to do the fuel mitigation around neighborhoods and around homes. Age makes a difference, elderly communities who may not be as mobile or have as many resources are also vulnerable and need greater assistance in times of evacuation. We also need to be concerned about those with pre-existing health conditions like asthma that make them vulnerable to smoke and smoke exposures. So there's a lot that we need to be working on and thinking about and helping communities and those whose lungs are in the way and whose homes are in the way we need to better protect people.

“I think we’re climate refugees” Korina said as she looked at the destruction of her home with her son Eric after it burned in the Marshall Fire in Superior, CO on New Year’s Eve. Their family had lived in the same home for almost 25 years. @nytimes pic.twitter.com/ksh1nKjqgR

— Erin Schaff (@erinschaff) December 31, 2021

CURWOOD:In your view, what could have been done to prevent the Marshall fire there in Boulder County?

BALCH:I think under those wind conditions, that fire was going to be pushed. I think, you know, let's start with where it started. That ignition start is still under investigation and that cause is still under investigation, but I can guarantee you that it was human related. There's no natural lightning at this time of year. So one thing we can do is to try and reduce the accidental ignitions that come from people. The other piece of this that we can tackle is making homes more fire resilient and building better. And then the last thing we can do that is the hardest, but we need to tackle is reducing the amount of greenhouse gases we're pushing into the atmosphere that are warming our planet and contributing to this problem. You know, in that we're all culpable.

CURWOOD: So you're both a scientist and a human who has been right next to this disaster. How do you feel?

BALCH: Yeah, it's hard. It's definitely hard. I have staff and friends and colleagues who've lost homes who are literally sifting through the ashes right now. And it's one thing to study it and it's one thing to face it. And, you know, I think for me talking about a winter wildfire this is, to me this is climate change in my face. And I hope that that message gets across because I think we need to do something about it. And, you know, do wonder, as a fire scientist and I've talked about warming related disasters before, how many do we need before we're proactive and I think the science community and our communities generally need to shift gears to solutions that are going to help us become more climate resilient.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Balch is director of the Earth Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder and a fire scientist. Thanks so much for taking time with us Jennifer and best wishes for a speedy recovery for your community there.

BALCH: Thank you and we're Colorado strong, we're going to build back I just want us to build back smarter.

Related links:

- Rocky Mountain PBS | “The High Winds That Fueled the Marshall Fire Are Not Unusual. Here Is How to Prepare.”

- The Washington Post | “More Than 40 Percent of Americans Live in Counties Hit by Climate Disasters In 2021”

- CPR News | “Why A Fire Scientist Sees Climate Fingerprints on the Suburban Boulder County Fires”

[MUSIC: The Head And The Heart, “Rivers and Roads” on The Head And The Heart, Sub Pop Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up after the break- The Center for Biological Diversity is taking the Biden Administration to court to protect polar bears from Arctic drilling but first this Note on Emerging Science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note On Emerging Science: Polar Bears Use Tools to Hunt Walruses

This illustration, from an 1865 book by adventurer Charles Francis Hall, depicts a polar bear using a rock to kill a walrus. (Photo: Charles Francis Hall, Library of Congress, Public Domain)

LYMAN: Weighing over 2,000 pounds, with large tusks and heavy skulls, walruses are a formidable arctic mammal. But research now suggests that polar bears may have found a way to kill the massive pinnipeds. For centuries, Inuit hunters in Greenland and the eastern Canadian Arctic have told stories about polar bears dropping large stones or blocks of ice onto walruses. Explorers and naturalists often dismissed these stories as myths. But the persistence of such stories, along with photos of a polar bear at a Japanese zoo using tools to obtain suspended meat, compelled biologists to investigate. Researchers reviewed historical and recent observations reported by Inuit hunters and non-Inuit researchers. They also looked at documented observations of polar bears and brown bears using tools in captivity to access food. The researchers concluded that “tool use in wild polar bears, though infrequent, does occur in the case of hunting walruses.” Tool use by animals to solve problems is generally regarded as a sign of higher intelligence, but studies on the cognitive abilities of polar bears are lacking. However, scientists say that a great deal of observational information suggests polar bears are very smart. Polar bears feed mainly on seals, which they hunt by looking for the seals’ breathing holes on sea ice. But climate change is melting Arctic Sea ice, so some scientists think that hungry polar bears may increasingly attack walruses for food. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

Read more on polar bears and walruses here

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Little Chief “Mountain Song” on Lion’s Den, Yellow Stone Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Polar bears are one of several Arctic species that would be threatened by oil and gas drilling exploration projects in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve near the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve. (Photo: Anita Ritenour, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. And on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia for our customary look beyond the headlines is Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hi there, Peter. Happy New Year!

DYKSTRA: Happy New Year, Steve. And we've got some news about polar bears, among other thing polar bears have become perhaps the enduring symbol of what climate change can do, is doing, to the Arctic. Just before Christmas, the Center for Biological Diversity announced a federal lawsuit against the Interior Department over a massive oil and gas exploration project within the Strategic Petroleum Reserve in the North Slope of Alaska.

CURWOOD: Well, that petroleum was right next to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and is almost as big and has many of the species that are protected next door there. And currently, it's free from oil and gas development.

DYKSTRA: That's right, the Peregrin exploration program would be a five year, almost year-round oil and gas effort, to see whether there is extractable oil and gas in a portion of the reserve. The Trump administration okayed the exploration, Biden's Interior Department would have to okay, the permanent oil and gas drilling there. But if it happened, it's hard to see that there wouldn't be the same kind of sizable damage that we fought over in the Arctic National Wildlife drilling proposals for the last 40 years.

CURWOOD: Of course, one of the concerns even about exploration is that it involves building snow and ice roads and air strips in areas where the permafrost itself, if it's disturbed, could become a source of methane and other gases for climate disruption.

DYKSTRA: That's right, noise pollution from all of that industrial activity is going to add to the burden of an area that has so far been pristine.

CURWOOD: And of course, the big question is, do we really need all this oil at a time of the climate emergency so maybe this lawsuit to protect the polar bears is really designed to protect us.

DYKSTRA: There's a 60 day comment period on the potential filing of the suit. Once that comment period ends in a couple of months, keep you posted on what happens with the proposal to drill in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter, well, tell me what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: A little good news. If you're concerned about plastic pollution in the world, after climate change, it's arguably the biggest worry for the environment and growing very quickly. But France has banned the use of plastics for in packaging, most fruit and vegetables. The ban came into effect the first of the year, under the new rules, everything from onions, carrots, tomatoes, potatoes, apples, pears, and about 30 other produce items can no longer be sold, wrapped in plastic. Instead, they should be wrapped at all in recyclable materials.

France has placed a ban on selling certain fruits and vegetables in plastic packaging as part of their process to phase out all single-use plastics by 2040. (Photo: Marco Verch Professional Photographer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, that'll be helpful because plastic pollution, as you say, is a major threat not just in the ocean, but to human health when it's used to wrap food because of chemicals that some food wrappings can contain.

DYKSTRA: That's right and foot in the door in France, so to speak, is hoped to be the first step for all of the EU nations to take in the effort to curb plastic pollution.

CURWOOD: Wouldn't it be nice that the United States thought the same way.

DYKSTRA: Wouldn't it be nice?

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, take a look back in the history books. Tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: Back in 1955, the first week of the year. And his State of the Union address President Eisenhower proposed the Interstate Highway System, which somewhat ironically, was based on what I saw in World War II, when Hitler guided the creation of the Autobahn system in Germany, not primarily seen as a way for Germans to zip across the country and leisure, but a way for German armaments and soldiers to zip across the country. In World War II, I’d wanted the same kind of mobility for the United States at a time when we were in the middle of the Cold War with Russia.

This photo from 1993 shows a ceremony unveiling the designs for the commemorative signs marking a highway as being part of Eisenhower’s Interstate System. L-R Chairman Nick J. Rahall (D-WV) of the House Surface Transportation Subcommittee, John Eisenhower (President Eisenhower's son), Federal Highway Administrator Rodney E. Slater, and Chairman Norman Y. Mineta (D-CA) of the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation. (Photo: Federal Highway Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So 65 years later, they're still building parts of the interstate system. Peter, right?

DYKSTRA: That's right and the interstate system, parts of it that are 65 years old or close to it are falling apart, which is a part of the infrastructure effort now underway in Washington.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news at ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the living on Earth website, that’s loe.org.

Related links:

- The Center for Biological Diversity | “Lawsuit Launched to Protect Polar Bears from Arctic Oil Exploration”

- The Guardian | “That’s a Wrap: French Plastic Packaging Ban for Fruit and Veg Begins”

- Read President Eisenhower’s State of the Union Address from 1955 here

[MUSIC: Nat King Cole, “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66, Capitol Records]

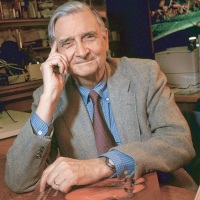

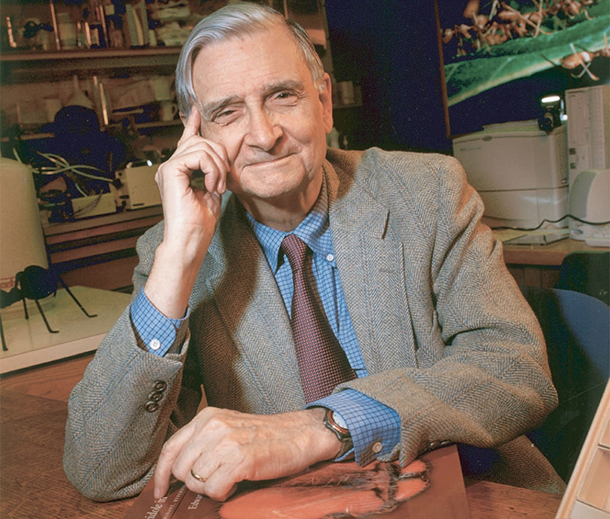

Remembering Naturalist E.O. Wilson

E.O. Wilson in his office at Harvard surrounded by images of the ants he studied as a myrmecologist. (Photo: Jim Harrison, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.5)

CURWOOD: The world lost several notable people in the waning days of 2021, including two leading naturalists, who died just a day apart at the end of December.

Edward, or "E.O." Wilson and Tom Lovejoy were pioneers in the field of conservation biology. And as they documented the steep declines in life on this planet they also gave clarion calls to protect it. Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson specialized in the tiniest of creatures and was nicknamed "Ant Man”. But his work on biodiversity took a planet-sized view of the extinction crisis.

WILSON: I like to call it, “One Earth, one experiment.” We've only got one shot at this. Let's be careful.

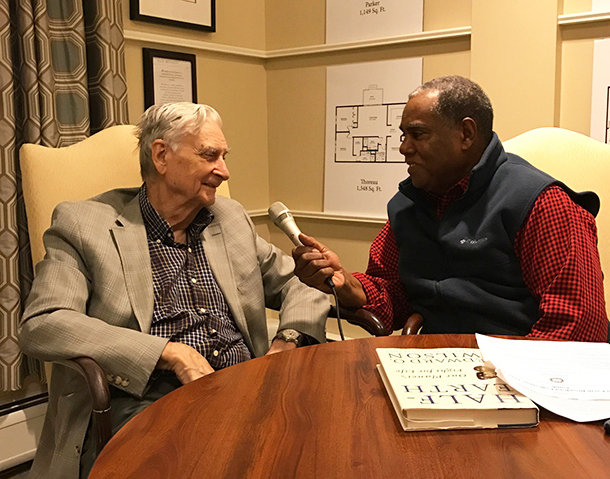

CURWOOD: In 2017 I sat down with E.O. Wilson at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts to discuss the big idea behind his book "Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life."

WILSON: What we need to do is try for a moonshot, and the moonshot is to set aside half the surface of the land and half the surface of the sea as a reserve, a reserve that doesn't exclude people by any means - Indigenous people are, in fact, encouraged to enjoy them and continue their way of life - but, if we could give half of the Earth primarily to the millions of other species that inhabit the Earth with us, then we would be able to save about 80 to 90 percent of the species, bring the extinction level down what it was before the coming of humanity. That would be a successful moonshot.

Wilson examining ants in Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

CURWOOD: That bold plan has inspired roughly 70 countries to commit to protecting at least 30% of their land and oceans by 2030 as a first step. Jane Lubchenco is a marine ecologist and Oregon State University Distinguished Professor who is currently serving as Deputy Director for Climate and Environment in the White House. She worked with both E.O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy over five decades and joins me now to help remember their work. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jane!

LUBCHENCO: Hey, Steve, it's so great to be here.

CURWOOD: It's so great to talk with you now, again. Now, each of these men were giants in the field of conservation biology in their own right, and we'll talk about Tom Lovejoy's work on forests and climate change in a few minutes. But first, let's talk about E. O. Wilson. What do you think were his most important contributions?

E.O. Wilson in Lexington, Massachusetts (Photo: Joel Johnson)

LUBCHENCO: Oh, my gosh, he made so many, it's hard to know where to start. Ed was a consummate naturalist. He was just a keen observer of the natural world. Obviously, ants were his passion and his lifelong love, you know, throughout his career. But he was able to build on those observations, and create really innovative breakthroughs in multiple areas. For example, he really pioneered new ideas about how ants communicate with one another. So breakthroughs in ant biology, ant pheromones, was one really big contribution. Another was what is called the Theory of Island Biogeography, which really focuses on, what are the guiding principles behind the number of species that you find on islands or in fragments of habitat? That was a theory that was both created mathematically, with Robert MacArthur, and then tested experimentally, with one of Ed's graduate students, Dan Simberloff. And that theory of island biogeography has really formed the foundation of modern conservation biology. It enabled people to think about, where do we want conservation parcels to be, how big should they be? How should they be connected to one another? Etcetera. Ed also, though, was a pioneer in creating new ideas about how people connect to nature, and how nature influences people. And he created this concept of biophilia, which suggests that humans have an innate connection to nature, they're drawn to nature. All of this was, you know -- many, many different contributions that he made. But again, grounded in very detailed, keen observations, but resulting in some grand theories and grand vision.

Wilson laid out his vision for protecting half the planet in Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. (Photo: W.W. Norton)

CURWOOD: Yeah, Ed Wilson was really amazing, and actually helped me in my work, Jane, I mean, obviously, covering the whole question of conservation and ecology. But as he laid out his biophilia hypothesis to me, that we evolved with all these other creatures, and there are things in our genes, or maybe we talk about epigenetics these days, I came to understand media. What do I mean? I came to understand that we evolved for many thousands of years not knowing the images or sounds of other people that we actually hadn't been with. And that I began to understand why so many people would treat people as almost members of their family that they didn't know, because they'd seen them on television or heard them on the radio or something. It's how certain, frankly, politicians got elected from Fred Thompson to Ronald Reagan. It is how if I, I said to you, isn't it a shame what happened to Tom and Nicole? You might know who I'm talking about, right? And it gave me a better understanding of how it is that we use images and voices in media. And I'm really grateful to Ed for that insight.

LUBCHENCO: You know, Steve, he really had a similar influence on many, many people. He was so adept at being able to explain something, but to do it in a way that would then trigger new thoughts on the part of the person he was interacting with. He was a very gifted teacher for that reason, you know, he would stimulate ideas and encourage others to sort of take them on to the next level and, and make them relevant to their lives.

CURWOOD: So tell me, just share with us a moment that you remember from working with, with Ed Wilson; I know there are many but what comes to mind?

Prof. Wilson with a katydid in Gorongosa National Park (Photo: Piotr Nasrecki)

LUBCHENCO: I was a graduate student at Harvard in the '70s, and then an assistant professor, and it was a time when there was a lot of tension in the Department of Biology, because molecular biology was really on the rise. And many of the leaders of molecular and cellular biology, but Jim Watson in particular, were very arrogant about ecology, evolution, systematics and really dismissed that field as just a bunch of stamp collectors. And, you know, being dismissed and marginalized to some -- and it was to Ed -- was very powerful motivation to show that, in fact, the science of ecology, of evolution, were actually legitimate in their own right, and not yesterday's science but tomorrow's science. And in the interim, we've seen a coming together of those threads in ways that is very exciting and appropriate. But at the time, there was this real tension. And Ed was bearing the brunt of much of this within the department. But being in his lab with his students, seeing these just extensive colonies of ants all over his lab, he would just light up and get so excited talking about his ants. And he would start talking about new big ideas, and the graduate students, the other folks who were in the room, it was just palpable excitement, that provided a really powerful antidote to a lot of the tension that was in the department more broadly. So just his excitement, his enthusiasm. He was, he was just like a little kid in a candy shop! He was just so over the top excited and it was infectious.

CURWOOD: It was! And, you know, Harvard wasn't very generous to E. O. Wilson to begin with, they didn't really want to give him tenure. And they thought that they were sticking him over in the museum with his ants. But you know, all through the years, he kept his office in the museum. And if you went by to see him, he'd show you the leaf cutters, those kinds of ants, he'd get all excited. What a gift. And I, you know, I think he kept the excitement right up to the end. So what do you make of his notion of half-Earth? How does that compare with the notion of, you know, conserving 30% of the biosphere by say, 2030?

Host Steve Curwood interviews E.O. Wilson at the ecologist’s home in Lexington, MA in 2017. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

LUBCHENCO: Ed was a big thinker, and he didn't do things halfway. But when he did them, they were solidly grounded in evidence, in good science. And through the years, and his extensive travels, he really became quite concerned about the sixth mass extinction event of biodiversity, the first one in the whole history of Earth that was being caused by people. And he saw firsthand the numbers but also the devastation in many different habitats. And he became very, very concerned about the future of the planet, the future of people, in part because we were losing so many species. And this led him to appreciate the importance of protected areas. And he developed this concept of protecting half of the planet for nature, an idea that many dismissed as completely impossible, because at the time, there was maybe 3% of the ocean that was fully protected, and maybe 17% of the land. So the idea of 50% was just mind boggling, and still is to many.

Jane Lubchenco and E.O. Wilson in his Harvard office in May of 2019. (Photo: Kathleen Horton)

Nonetheless, he became a staunch champion, very eloquent in his speaking and his writing, focusing on the importance of saving nature, not only for its own sake, but also for our sake. And that concept has gained a lot of support from colleagues and others. The fact that many countries are focused on 30% is quite remarkable, actually. It, you know, remains to be seen how effective that protection is; it really is important what type of protection, you know, something that is fully protected is really, really different from something that's only lightly or marginally protected. So the devil is in the details with respect to the execution. Nonetheless, his idea was a bold challenge, and an inspiration to many people.

CURWOOD: So E. O. Wilson was a giant, certainly in this field of biological diversity. And oh, by the way, he happened to have a couple of Pulitzer Prizes for his nonfiction writing about ants and things, and he will be talked about for many generations.

Related links:

- Listen to the Tom Lovejoy part of this interview

- Elizabeth Kolbert for The New Yorker | “Honoring the Legacy of E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy”

- Listen to LOE’s 2017 interview with E. O. Wilson on his book “Half-Earth”

- NYTimes | “E.O. Wilson, a Pioneer of Evolutionary Biology, Dies at 92”

- Jane Lubchenco’s statement paying tribute to E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy

- About Jane Lubchenco

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Dedication” on Natural Essence, High Note Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up after the break – We’ll continue our chat with Jane Lubchenco and talk about another conservation giant we lost last year, Tom Lovejoy. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Dedication” on Natural Essence, High Note Records]

Remembering Naturalist Tom Lovejoy

Ecologist Tom Lovejoy is being remembered for his decades of research and bringing people together to protect the Amazon rainforest and other ecosystems on the planet. (Photo: courtesy of Carmen Thorndike)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Like E.O. Wilson, biologist Tom Lovejoy dedicated his career to not only studying life but also communicating the biodiversity crisis to the public. He spoke with Living on Earth back in 2010 about a growing awareness of this emergency, and UN efforts to deal with it. Let's share a clip from that interview.

LOVEJOY: I think what’s driving it today is a greater sense of urgency than before because people can see a lot of this biodiversity beginning to slip away. That finally makes you focus and spend less time negotiating and more time thinking about how to actually protect the biology of the planet and indeed the human future.

CURWOOD: Tom Lovejoy’s work focused on tropical rainforests and he was famous for showing the amazing diversity of life in the Amazon as well as telling about it. Over the years he hosted politicians including Vice President Al Gore and celebrities such as Olivia Newton-John at Camp 41, a research station deep in the Amazon where people slept in hammocks to reduce the odds of scorpions creeping into their sleeping bags. Around the station there were creatures and plants never before recorded by science in the Global North. And when I visited Camp 41 in 2002 and got to see a scientist document a previously unrecorded potoo, that’s a species of bird, I too went from seeing biodiversity as just an intellectual construct to feeling it as real and exciting. We’ve been talking about the legacies of Tom Lovejoy and E.O. Wilson with biologist Jane Lubchenco, who currently serves as deputy director of Climate and Environment in the White House. Jane, how did Tom Lovejoy shape our understanding of the importance of keeping this vital ecosystem intact?

Tom Lovejoy holding a Cecropia leaf at Camp 41 in the Amazon in 2014. (Photo: Slodoban Randjelovic)

LUBCHENCO: Tom first went to the Amazon as a graduate student, and he was focused on birds. And according to him, he just really fell in love with the whole rainforest. And at the time, there was increasing logging that was happening in the Amazon. And he quickly appreciated what a potential threat that was to the health of the rainforest ecosystems, not only to the birds that he cared about, but to the mammals and the insects and the trees, etc. And he was inspired, in fact, by the work that Ed Wilson and Robert MacArthur and Dan Simberloff had done on island biogeography. And he started thinking about, how does the size of the parcel that remains in the rainforest after logging happens affect the biodiversity? And at the time, there was a raging controversy in the conservation world, it was called the SLOSS debate, S-L-O-S-S, and it stood for "Single Large Or Several Small" parcels. And the question was, if you are in a position of creating habitat for biodiversity, is it better to have one single large parcel, let's say ten acres just for the sake of argument, or ten smaller, one acre parcels. And there were arguments on either side, having to do with, well, if it's a single parcel, wildfire, disease, might wipe out the whole thing; if it's divided up into smaller ones then at least some of them could persist. Versus the idea that some of the very large, very mobile critters, let's say a panther, for example, might need a very, very large habitat. And so you would lose those big charismatic species if you had only small parcels. So there was a debate. And Tom said, let's test this idea; this is the scientific approach. And so he worked with colleagues in Brazil, worked with landowners and the government and created this experiment that is still ongoing today. And it was created in the late '70s, I think, maybe '79. And the experiment was essentially to create parcels that were one, ten, or a hundred hectares, and then follow them through time and see how the biodiversity changed in those parcels. Those experiments have given us a huge amount of information about how size of the parcel affects the type of species that are there, and the health of the whole system. And in fact, there is no doubt that larger parcels are better. And so that early experiment of Tom's has yielded a huge amount of information that is guiding conservation action today.

Tom Lovejoy first went to the Amazon as a graduate student to study birds and fell in love with the whole rainforest. Here he is with a group of curious lemurs. (Photo: courtesy of Carmen Thorndike)

CURWOOD: So Tom Lovejoy was also well known for, for telling the story of the Amazon and biological diversity. And he attracted a swarm of politicians and celebrities who would either visit him in the Amazon or just pay attention to what he was doing and saying; what was Tom's skill there? How was it that he was able to, to bring these types of folks to the story of biological diversity and why we needed to, to hang on to it?

LUBCHENCO: Tom was a gifted communicator, but he was also a connector. And he understood people, he understood what would be of interest to someone. And he would very carefully make an argument to someone about why they should be interested in the Amazon or biodiversity or birds or whatever it was. So part of Tom's legacy is this gift that he had for sharing the excitement, enthusiasm, and passion that he had for nature with others, and in training them in this vision of respecting nature, protecting nature, living with nature. And he understood how important it was to do that with local people. Much of the work that he did in the Amazon was with Brazilian students, Brazilian scientists, Brazilian politicians also went to Camp 41. And so it was not a nature versus people thing. It was very holistic. And the same was, was true -- you know, Ed also appreciated the importance of, of working with people. But Tom in particular, really took that home and made it real. And now there are many, many young Brazilian scientists that are spectacular in part because they sort of got their start with Tom.

Lovejoy in a deforested section of Amazon rainforest c. early 1980s (Photo: courtesy of Carmen Thorndike)

CURWOOD: So Jane, if you could pick one memory from working with Tom Lovejoy, what would come to mind?

LUBCHENCO: Mmmm... I spent a lot of time with Tom in a lot of different venues. But I think his home, that he called Drover's Rest in McLean, Virginia, was a very special place. He often would have dinners there. Fantastic food, great wine; his wine cellar was quite extensive, and people knew that Tom was quite the oenophile. But he would gather unusual groups of people together and have these engaging conversations. Always a fire in the wintertime, fire going in the fireplace in this old cabin that just had a lot of character. And Tom was such a gifted host, everybody would be comfortable but he had given a lot of thought to the people he was introducing to one another, so it wasn't just the same group. Oftentimes, when I would be there, it would be everybody was new to me, or I might know only one other person. And so he was always matchmaking. And always with the idea of stimulating conversation that would be intriguing, interesting, we could learn from one another, but also result in some higher purpose focused on conservation, on nature, on big ideas, on getting something done. So, you never felt like you were being manipulated, it was always a very natural, very engaging enjoyment, and anybody who went to Drover's Rest would always say yes the next time because it was such a very special experience.

Tom Lovejoy at Camp 41 in the Amazon rainforest (Photo: Zachary Smith)

CURWOOD: It was, it was like in fact, being inside a, it reminded me of an old sailing ship, a big old sailing ship, that being inside that cabin that I was somehow in the captain's quarters in some big old ship with the big timbers there. And Tom always cracking a joke, not over the top, but just making light and having fun --

LUBCHENCO: Yep.

CURWOOD: -- with, I don't know how many bow ties the man owned, but not sure I saw the same one twice.

LUBCHENCO: He had a lot of bow ties. And that was always very special, because my dad was a bow tie guy too. The first time I saw Tom, I think I liked him just because he was wearing a bow tie!

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So how do you think Ed Wilson and Tom Lovejoy's work should be remembered?

Hammocks and mosquito nets in the sleeping quarters at Camp 41 (Photo: courtesy of Amazon Biodiversity Center)

LUBCHENCO: Well, both were gifted scientists. They took very different paths; Ed was an academic who did just one discovery after another after another. And then he came around to appreciating the biodiversity crisis and being a leader in saving biodiversity. Tom took a very different path. He was more a scientific adviser, a scientific communicator, an instigator of new conservation oriented things. So different paths, but they ended up very much in the same place of being champions for biodiversity, and eloquent communicators, through their writings, through their speaking, to motivate people to care about nature, and to help be part of the solution. Their legacy lives on, in our hearts, in our minds. And we need to do justice to their legacy by taking up the mantle of what they were working on. It's time for all of us to come together.

From left to right: Tom Lovejoy, Jane Lubchenco, and atmospheric scientist Bob Watson, all Blue Planet Prize recipients, speaking to the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan in Tokyo 2017. (Photo: Blue Planet Prize of the Asahi Glass Foundation)

CURWOOD: Jane Lubchenco is a marine scientist and former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, among many honors, and she currently serves as the Deputy Director for Climate and Environment in the Biden White House. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LUBCHENCO: Steve, it's just my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Listen to the E.O. Wilson part of this interview

- Elizabeth Kolbert for The New Yorker | “Honoring the Legacy of E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy”

- Listen to LOE’s 2010 interview with Tom Lovejoy on saving the world’s biodiversity

- The Washington Post | “Thomas E. Lovejoy III, an ecologist who dedicated his career to preserving the Amazon rainforest, dies at 80”

- Jane Lubchenco’s statement paying tribute to E. O. Wilson and Tom Lovejoy

- About Jane Lubchenco

[MUSIC: Bill Evans, “Peace Piece” on Everybody Digs Bill Evans, Concord Music Group]

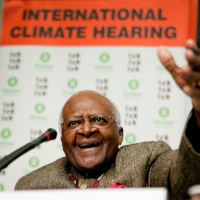

A Call to Climate Action from Desmond Tutu

Desmond Tutu at Oxfam's Climate Hearing at the COP15 talks in Copenhagen, December 15th, 2009.

CURWOOD: Within the same 48 hour period at the end of December that famed biologists Tom Lovejoy and E.O. Wilson died, Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa also passed away. Archbishop Tutu will be remembered as a leading non-violent opponent to South Africa’s rigid system of racial segregation known as apartheid and as a leading proponent of human rights. He was also an outspoken advocate of environmental protection and justice. Here is an excerpt of his call to action on the climate emergency as nations gathered in Copenhagen in 2009.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, who worked as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. (Photo: Benny Gool. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

TUTU: The whole world stands faced with a common threat of climate change. This global threat already affects us all, in particular, the poorest and the most vulnerable. That alone should move all governments to act. But my heart is heavy, when I imagine the devastation that we will face our children and our children's children, if we do not act now, to stop it. The final measure of a generation's courage is the memory of what they have done. We must live in memory. As the generation that pulled humanity back from the brink of catastrophic climate change, droughts, floods, and water shortages are already on the increase because of climate change. Science has spoken on the urgent need to tackle the challenge. Now, it is time to listen to our consciences. There is a clear moral imperative to tackle the causes of global warming. We're part of nature. Yet we alone can act. Our destiny must be as guardians of the earth, not users and abusers of the only home we have. We all have a responsibility to learn how to live and develop sustainably. In a world of finite resources. We must make peace with this planet.

[MUSIC: Bill Evans, “Peace Piece” on Everybody Digs Bill Evans, Concord Music Group]

CURWOOD: The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu in a message to the Copenhagen UN Climate summit in 2009.

Related links:

- Global Citizen | “Desmond Tutu: The World Pays Tribute to South Africa’s Anti-Apartheid Hero”

- Read an opinion piece by Archbishop Tutu from 2014 urging action on climate change

- Watch a video of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Speech during the 2009 Copenhagen climate talks

[MUSIC: Bill Evans, “Peace Piece” on Everybody Digs Bill Evans, Concord Music Group]

Adiós Al Color

The landscape in Great Sand Dunes National Park. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Biological diversity is everywhere on our planet so as an example, now that winter has settled in over the northern hemisphere, we turn to Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender. Here is Mark’s description of elk passing the winter in Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes National Park.

Adiós Al Color

Great Sand Dunes National Park

Colorado

© 2021 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

The lake is black. The creek comes to an end there in one deep gulp. On the far side the curve of the lake shore is high, rising in a cliff. Beneath that cliff a cluster of shapes detaches from the sand and rock and gravel. Elk. Browns and tans. How small they seem. And even smaller when considered against what looms above so large they appear closer than they are, the Great Sand Dunes, yellowish-red as the sun sets; violet, in the approaching dark.

In the dark the land grows spare and wide. The eye, the pulse, the mind adopt the presence of absence.

One of the elk shambles over to the edge and drinks. The others wait - then on the move. At first slowly. Faster. Galloping!

Their hooves on hard ground, the leap-loping run and the clods of earth tossed head-high. Creosote bush and sage part in the rush of them. They speed westward chasing the last light into obscurity.

A herd of elk start to gallop. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Morning is its own impossibility. Snow. Thick as plaster. The creek, the cliff, the lake, erased. A creamy layer swirled to the contours of the dunes; as if what lies beneath is not earth but cake.

It’s true, proved by the progression of seasons and just as much by the passage of a single day. The only permanence is change.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Find the field note for this essay

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella “Elevate” on Elevate]

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth