January 14, 2022

Air Date: January 14, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Lead Pipes and Mental Health

View the page for this story

Lead contamination in drinking water can have serious impacts on growing brains, including cognitive issues in the short term and mental illnesses years after the exposure ends. Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News, which published a 5-part series about how air, water, and climate pollution shape our mental health. She joins Host Bobby Bascomb. (09:04)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra talks with Host Jenni Doering about a recovering population of New Zealand sea lions. They’ve begun to show up in swimming pools and front lawns, creating conflicts with people. Then the two discuss how climate change is leading to more thunderstorms in the Arctic. In the history calendar Peter and Jenni go back one hundred years to when the Izaak Walton League of America was created by anglers concerned about polluted waterways. (04:46)

Mapping Cancer-Causing Air

/ Lisa SongView the page for this story

Millions of Americans are breathing toxic air pollution emitted from industrial facilities, often without their knowledge. The nonprofit investigative newsroom ProPublica recently created an interactive map that highlights the EPA’s failure to account for cumulative cancer risk for Americans who live near several industrial facilities. Lisa Song is a climate and energy reporter with ProPublica and discusses the team’s findings with Host Bobby Bascomb. (12:14)

Fishing for Data on Chemical Runoff

/ Katie WatkinsView the page for this story

Houston, Texas is a hub for the US petrochemical industry and just downstream is Galveston Bay, an important ecosystem and fishery for the region. Houston Public Media reporter Katie Watkins reports on research to test fish living in the Bay for chemical exposure from run off. (03:52)

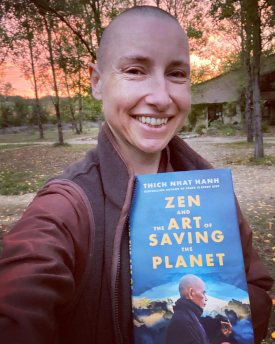

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

View the page for this story

The Zen Buddhist practice of mindfulness can help us break out of a destructive cycle of consumption and live in harmony with the planet, according to the 2021 book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet” by Zen teacher and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh. His student, Sister True Dedication, edited the book and joins Host Jenni Doering to share insights about how mindfulness can provide an antidote to burnout and a source of energy to all who care about climate and environment. (15:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220114 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Sister True Dedication, Kristina Marusic, Lisa Song

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Katie Watkins

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

A blind spot in the way the EPA calculates industrial exposure and cancer risk.

SONG: You know, they're slicing and dicing the risk in a way that if you live near two refineries, they will look at the risk from both of those refineries together. But if you live next to a refinery and a chemical plant, then the EPA is not going to be looking at the total risk from both of those, because they're considered two different types of facilities.

BASCOMB: Also, a Buddhist prescription for happiness and saving the planet.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: It is our ideas of happiness that have led us into this current situation. So we think happiness lies in consuming. But in the essence of our Zen Buddhist teachings, we know that this beautiful earth, this extraordinary planet, already gives us so many conditions for happiness.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Lead Pipes and Mental Health

Lead contamination in drinking water is linked to a number of health issues, including cognitive and learning difficulties, as well as psychiatric disorders. (Photo: Nenad Stojkovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

There is no safe level of exposure to lead yet roughly 186 million Americans are drinking with lead levels above 1 part per billion. That’s the level set by the American Academy of Pediatrics to protect children from lead in school water fountains. Lead contamination in drinking water has been linked to a host of health problems, from anemia, and hearing loss, to learning disabilities especially in children.

And now a growing body of evidence shows a connection between water polluted with lead and mental health problems. Investigative reporter Kristina Marusic has been digging into that relationship as part of a series on mental health and pollution for Environmental Health News. She focused her reporting on Western Pennsylvania, one of the worst regions in the country for lead contamination in water. Kristina Marusic, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MARUSIC: Hi, Bobby, it's great to see you again.

BASCOMB: You know, we know that lead, of course is especially problematic for children and learning disabilities. But our listeners might be surprised to hear about a host of mental health issues associated with elevated lead levels. Can you tell us about some of those, please?

MARUSIC: Yeah, so scientists are just kind of beginning to figure out that, in addition to causing some of those learning and behavioral and cognitive problems in kids who are exposed to lead, the effects of lead exposure can show up as mental illness much, much later in life. So maybe not even until someone who was exposed to lead as a kid reaches middle age. So I spoke with one researcher who led a 2021 literature review that looked at several dozen human and animal studies on lead exposure, and it found increasing evidence that childhood lead exposure is a risk factor for psychiatric disorders in adulthood, including anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorders, and then also for neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD, autism, and Tourettes syndrome. And the largest one of those studies, so again, he looked at a whole lot of studies in both people and animals to do that literature review, but the biggest one looked at 1.5 million people in the US and Europe, and found that people who had higher lead exposure as kids were more likely to have negative personality traits like lower conscientiousness, lower agreeableness, and higher neuroticism once they reach adulthood, all of which contribute to mental illness.

Towns with water pollution like Braddock, PA are often also battling with air pollution and environmental injustice. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie)

BASCOMB: So what is the mechanism here by which lead is contributing to mental health problems?

MARUSIC: So scientists are a lot clearer on how lead impacts the brain than they are about air pollution, which they're still kind of trying to figure out. Lead exposure impacts a protein receptor in the brain that's known as the NMDA receptor, and I'll say it but it's a very, very long word. NMDA stands for N-methyl-dextro-aspartatic acid receptor. So we'll stick with NMDA, and that receptor is critically important for brain development, learning and cognitive function. And improper functioning of the NMDA receptor is also seen in the brains of people with certain mental illnesses, including schizophrenia. So the NMDA receptor influences the development of inhibitory neurons that help keep the brain balanced. And when it's damaged by lead exposure, it creates too few of those neurons. So you can imagine in a healthy brain, you have excitatory neurons and inhibitory neurons, and they maintain this kind of exquisite balance where, you know, there are an equal amount of both, and it keeps everything in check. And if that's interrupted, and you have too many of one or the other, the balance is thrown off, and that can manifest as mental illness.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. Well, we last spoke to you regarding your article on air pollution and its effects on mental health. To what extent are these sort of overlapping issues? Do you often see, you know, where you have air pollution, you also have this problem of contaminated drinking water, and to what extent is that, you know, the problem sort of magnified?

MARUSIC: Unfortunately, communities that have problems with childhood lead exposure are also likely to experience other issues that can disproportionately impact people's health. And that includes other environmental exposures like air pollution, which also can impact both physical and mental health. It also includes things like community violence, racism, and poverty. And so all of these factors kind of overlap to create combined physical and mental health impacts, that can be really detrimental. But there's also emerging evidence that one harmful exposure from something like air pollution changes the brain in a way that can magnify the effects of another harmful exposure later on. So scientists are kind of just learning that it might not be an additive effect, where one plus one equals two, but more of a synergistic effect where if you're getting one hit from lead exposure, and one hit from air pollution exposure, they actually combined to be more like three or four hits. So there's a lot of concern that you know, these overlapping impacts are having a magnified effect on these communities that face more than one issue.

BASCOMB: And you're right, that even normalizing for income, unsafe drinking water is more of a concern for many minority communities. What's going on there?

MARUSIC: Yeah, so, some research has shown that regardless of income level, black children in the United States are two to three times as likely as white or Hispanic children to experience lead poisoning. And the thinking is that this is, in part, a lingering effect of racist practices like redlining, where black community members specifically were kept out of certain communities. And that then, you know, as time moved along, these black communities were less likely to have their lead lines replaced, and more likely to deal with other types of pollution and water contamination. So it definitely is an environmental justice issue. If you look at many of the communities that have kind of made headlines for having lead in the drinking water, many of them are majority black communities. So this is a story we see play out again, and again, in the United States.

BASCOMB: We know that there's no safe level of lead. And at the same time, we know that millions of Americans are drinking water that's contaminated with lead. But remediation, you know, replacing those lead pipes is is really expensive. I mean, is that basically what this boils down to, in terms of, you know, creating a safer drinking water system for the country?

Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News. (Photo: Courtey of Kristina Marusic)

MARUSIC: Yeah, so a lot of it comes down to aging infrastructure and the need to replace lead pipes. One of the big challenges there is that, if you replace just part of a lead line, and not the entire water line, it can actually result in more lead being in the water temporarily, because replacing part of the line kind of jostles and shakes loose the part of the line that's left in place in a way that can cause more lead to like flush into homes. So when they replaced lead lines, at least for the the big major main water authority here, not for some of the smaller ones, they are required to do a full lead line replacement at no cost to the homeowners. So if they're replacing the line under the street, they also have to replace the lines that go into everyone's homes at the same time. And if there's a delay, if initially, they replaced the part into the street, they also have to notify people that they should use a filter to make sure that they're not getting exposed to extra lead when it's kind of jostled loose during that process. So there's a lot that goes into that, you know, your question was, is this kind of the fundamental problem and the issue is that there are so many considerations and these projects are big and expensive. You know, a lot of times cities and municipalities are just strapped for cash. And it's just an issue of not having the budget to do all these lead line replacements.

BASCOMB: Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News. Kristina, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

MARUSIC: It was great talking to you. Thank you.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “How Contaminated Water Contributes to Mental Illness”

- Listen to our previous conversation with Kristina Marusic about air pollution and mental health

- Click to see the full 5-part series from Environmental Health News

- Kristina Marusic’s website

[MUSIC: Chris Smither, “Small Revelations” on Small Revelations, by Chris Smither, Hightone Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Baby sea lions resting on New Zealand’s Enderby Island. (Photo: Roderick Eime, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It's time for our look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi, Peter. How you doing?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Jenni. I'm going to talk about a subspecies of a marine mammal that I had never heard of before. The New Zealand sea lion was victim of the same thing that so many other marine mammals have fallen victim to: human predation. The sea lion survivors were driven completely off New Zealand's main islands, and on to some very icy, cold, windy rock piles, about 300 miles south. Recovery efforts, however, have been so successful that the sea lion population has grown from dozens to about 12,000. The bad news in all of that is they have begun to show up again, on South Island on some yards and lawns and swimming pools and gardens. Imagine waking up to see a sea lion doing the backstroke in your pool.

DOERING: What an amazing recovery. I think you said dozens to 12,000 now, but this sounds like a pretty big conflict for the sea lions and the people living there.

DYKSTRA: Well, here's what makes it worse. The female sea lions in this population move about a mile inland to give birth. And the human interactions can be really ugly there. Sea lions have been stabbed, clubbed, shot and accidentally hit by cars. Some females and pups have adapted by moving to commercial pine forests that could someday be cleared or developed.

DOERING: It's so sad how they're being treated, and that they're now essentially homeless. Are there any solutions in sight?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the sea lion researchers have identified hundreds of potential sites for sea lions to find less opportunities for conflict. The challenge then becomes getting both the sea lions and the humans to avoid each other.

DOERING: I imagine this must be happening with other species too— ones that are bouncing back as well as those on the move because of climate change. Hey, Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, extreme weather was big news all over the globe in 2021. But at the top of the world, the northern Arctic, there was an unprecedented increase in lightning. Scientists point to that as another clear sign of how the climate crisis is affecting global weather.

Thunderstorms form when warm, moist air rises into cold air. When there’s enough air moisture and water vapor a thunderstorm can form. (Photo: Steffen I, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Gosh, I mean, that's incredible. I guess Zeus must be pretty displeased with what we're doing to the planet. But how exactly does climate change lead to more lightning, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, the turbulence that comes with a changing climate. It's cold in the Arctic, but it's never been this unstable. And when cold fronts hit warm fronts, lightning results. And lightning strikes can cause brush fires when the Arctic is unusually dry. Those brush fires further heat up the permafrost in the Arctic, that releases a tremendous amount of climate killing methane gas. And we're seeing signs that that's happening on an increased level as well.

DOERING: Wow, so more lightning in the Arctic. I guess this is just one more reason to call it "Global Weirding." Hey, Peter, if you look back in history, what do you see this week?

DYKSTRA: This week in January 2022, 100 years ago, 54 avid sports fishermen met in Chicago and agreed to launch a new national organization, the Izaak Walton League, making it a nationwide force to protect streams and wetlands.

The Izaak Walton League was created in 1922 with a mission to protect rivers and waterways. (Photo: Brianjan607, Flickr, CC BY-ND-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Well, what prompted this? What brought these 54 sport fishermen together?

DYKSTRA: While fishing, there were fishermen and fisherwomen who saw the tremendous impact that pollution was having on both fresh and saltwater. They named their organization after historic icon, Izaak Walton, who was a 17th century English conservationist, and the organization lovingly nicknamed, "The Ike" is a vanishing link between mostly liberal environmental groups, and generally more conservative hook and bullet conservationists.

DOERING: Well, a very happy 100th birthday to the Izaak Walton League. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Always a treat, Peter. Thank you so much.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Jenni, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The Conversation | “When Endangered Species Recover, Humans May Need to Make Room for Them – And It’s Not Always Easy”

- The Guardian | “‘Drastic’ Rise in High Arctic Lightning Has Scientists Worried”

- Learn more about the Izaak Walton League of America

[MUSIC: Darol Anger with Bruce Molksy, “Voodoo Chile” on Diary of a Fiddler, by Jimi Hendrix/arr.Anger, Compass Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A new tool for looking at elevated cancer risk from multiple industrial exposures. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mongo Santamaria, “Dawn’s Light” on Brazilian Sunset, by Mongo Santamaria, Candid Records]

Mapping Cancer-Causing Air

A refinery in Houston, Texas, where the petrochemical industry sends significant amounts of carcinogenic compounds into the air, raising the risk of developing cancer. (Photo: Louis Vest, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Air quality in the United States has improved a lot since Congress passed one of the strongest environmental laws in U.S history, the Clean Air Act of 1970. Smog, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and more have declined over all and most Americans can breathe easier. But many of us still suffer from toxic air. In some neighborhoods located near industrial areas, air pollution far exceeds levels considered acceptable by the Environmental Protection Agency. Those air pollutants include carcinogens like benzene, ethylene oxide, and the heavy metals chromium, cobalt, and nickel. And until now if you wanted to know about the extra cancer risk you could face from living near these sources you were out of luck. Now in a first-of-its-kind map and data analysis the nonprofit investigative newsroom ProPublica has yielded new insights into how multiple sources of industrial carcinogens can add up to elevated cancer risks for local neighborhoods. Lisa Song is a climate and energy reporter at ProPublica and part of the team that put together the analysis. She’s also a former Living on Earth intern and joins me now from New York City. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Lisa!

SONG: Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So what's new about this mapping tool? What are you trying to show here?

SONG: What we're trying to show is the cumulative industrial cancer risk from major sources of toxic air pollution. And this is important because the way the EPA normally assesses industrial cancer risk is they do it for one type of facility at a time. And so that often underestimates the estimated cancer risk because so many people are living in close proximity to several different industrial facilities at once.

BASCOMB: And so how can you use this, as a user, if you go to the ProPublica site, how can a person use this information that you've put together?

SONG: So we put this data together into a searchable map, so you can type in your home address or your work address, and it will zoom in to your exact place and show you at a very localized level the estimated additional cancer risk from these big industrial facilities in your area. And if you live in one of those places where you don't have a facility nearby, it will tell you that, you know, the nearest facility is six miles away, or 10 miles away, or whatever the number is. You can also just put in the name of a town or a city. And it will give you a kind of city wide overview to say, you know, this area with a population of roughly this many people, you know, the largest estimated cancer risk in this area is x and the average is y, something like that.

BASCOMB: And so just to be clear, this is EPA's data and it's going into your database.

SONG: Yes, the raw data from this comes from the EPA. And what they've done over the years is they take the annual data that the industries report to EPA about how many pounds of benzene or how many pounds of chromium they emit into the air every year. And then the EPA runs its own air model on these emissions, to model out where the emissions are going, kind of, where they go geographically and the concentrations at places on the map. And so all of this raw data has been in EPA's possession for, for many years. And what ProPublica did is we analyzed it and put it together in a way to make it searchable and usable and practical for the public.

BASCOMB: And so you identified more than a thousand hotspots around the country where industrial sources emit carcinogenic air pollution. Where are they generally located?

SONG: Most of these hotspots are in southern states. So the top hotspot on our map is what's known as Cancer Alley in a part of Louisiana. And then other top hotspots are, there's one near Houston, and then there's one in Orange, Texas,

BASCOMB: This is the same area where they're looking to expand, and we've covered some stories in the past on the show about ethane crackers and looking to site new ethane cracking facilities in the same area where people already have an elevated health risk associated with industry. And EPA knows about it, it almost seems like these are just kind of sacrifice zones.

SONG: Yeah, and that, that is the term we and others have used to describe these areas. And it's important to remember that this is simply how our regulatory system is set up. It was not set up to adequately account for cumulative risks. The way the EPA assesses risk, you know, they're slicing and dicing the risk in a way that, for example, if you live near two refineries, they will look at the risk from both of those refineries together. But if you live next to a refinery and a chemical plant, then EPA is not going to be looking at the total risk from both of those facilities, because they're considered two different types of facilities. So that oversight is baked into the way that the EPA does its regulations right now. And when we spoke with EPA officials, they did say that the Biden administration plans to take a look at this and perhaps have a new approach. But that's something that's going to take time. So right now, you know, we have not seen that concrete action yet.

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk about one of the people that was featured in your article. Tell me about Brittany Madison, please.

(Left) Baytown resident Brittany Madison gives her 3-year-old niece, K’ryah, an asthma treatment, which K’ryah takes twice a day. (Right) The ExxonMobil Baytown complex is seen from Oklahoma Street in Baytown. (Photo: Kathleen Flynn for ProPublica)

SONG: Sure. Brittany lives in Baytown, which is near Houston, and she lives with her family. And they live next to many, many different industrial facilities. So Brittany's apartment is within 30 miles of more than 170 facilities that give off toxic emissions. And we looked at the three facilities that account for most of the risk on her block. Those facilities include an ExxonMobil refinery and then two other large facilities. So if you look at the risk of each of these facilities in isolation, the risk is relatively low. So the refinery, for example, increases the estimated risk of getting cancer on her block by about 1 in 730,000. And then, you know, the two other facilities are somewhere in the range of 1 in 100 [thousand] or 200,000. But then when you add up the combined risk from all three facilities, plus all the other facilities in the area, the estimated additional cancer risk jumps to 1 in 46,000. So you can see how quickly these combined risks add up together. And when we spoke with Brittany, she talked about how her niece, who's only three years old, has asthma and needs asthma treatments, how she and her family have suffered from headaches and migraines and other ailments, particularly after an industrial accident at the refinery a couple of years ago. She's had family members who have died of cancer, she's had family members who have worked for the industrial sector. And one thing to keep in mind about our map in our reporting is it's very difficult to prove that a particular person's cancer was caused by a particular type of pollution. But we do know that these air pollution risks compound cancer risk overall.

BASCOMB: I believe you said her cancer risk, when you overlay all of these these hazards, is 1 in 46,000. What is the EPA threshold, if there is one for concern? I mean, at what point is there some sort of intervention, even?

SONG: So the EPA, their main general threshold for cancer risk is 1 in 10,000. But they also don't use 1 in 10,000 as an absolute cutoff point. At the same time, the EPA actually has an aspirational goal of minimizing the number of Americans exposed to industrial risk higher than 1 in a million. So certainly by the 1 in a million standard, the place where Madison lives, that cancer risk is much, much higher than the 1 in a million goal. But it is lower than the 1 in 10,000 that EPA typically considers an upper limit.

BASCOMB: And I believe you even drill down further into the US population as a whole to see where we lie in the spectrum of cancer risk. What did you find there?

SONG: Well, in terms of the EPA's aspirational standard, we found that 74 million Americans live in places where the estimated risk is greater than 1 in a million. And that's something like a fifth of the US population. If you're looking at places with higher than 1 in 10,000 risk, which the EPA generally uses as an upper limit, then about a quarter million people live in those places. You've got places like Cancer Alley, certain parts of Texas, but also other states as well. There's a lot of smaller pockets of hotspots in places that maybe the residents don't even know they're living there.

Brittany Madison walks her nieces and nephew to the apartment they share with her sister in Baytown, Texas. (Photo: Kathleen Flynn for ProPublica)

BASCOMB: And Brittany Madison is African American, and we know that communities of color tend to bear out more pollution burden than predominantly white communities. To what extent were you able to quantify that risk for black communities using this mapping tool?

SONG: Yeah, so our national analysis showed that in census tracts that are mostly people of color, they experience about 40% more pollution than census tracts that are mostly white residents. And in mostly black census tracts, they're being exposed to more than double these pollutants than predominantly white census tracts. So it really is something that confirms the decades of research that have shown how pollution is segregated, and pollution is concentrated in communities of color.

BASCOMB: You know, how do you hope the public will use this tool that you've come up with?

SONG: I think the first thing is we just want the public to be aware and to you know, search for their own homes, to search for their friends' and families' homes and see, are you living in an area that is a hotspot? And if so, we've actually published a guide for residents in hotspots that explains to them, what are the types of things that community groups in other hotspots have done historically? The guide, we hope, will perhaps give them more context to our findings and help alleviate certain anxieties. The guide also explains that very organized communities in Cancer Alley, for example, they have done things like campaign for regular air monitoring. They've looked for funding to conduct their own independent air monitoring. Some communities have done things like worked with the facilities so that they're all notified whenever the facility has some kind of unexpected accident. Other people have purchased air filters to use inside their homes to make the air a little bit safer indoors, and other communities even have worked with lawyers and filed lawsuits. So there's really a whole bunch of things that these types of communities have done historically. And we're hoping that our guide can just help inform and perhaps empower people who are discovering they're in hotspots for the first time.

BASCOMB: Lisa Song is a climate and energy reporter for ProPublica. Lisa, thank you so much for this wonderful tool and for chatting with me today.

SONG: Thanks.

BASCOMB: We reached out to EPA to ask about potential plans to change the way they assess cumulative risk from industrial exposure.

Related links:

- ProPublica | “Poison in the Air”

- ProPublica | “The EPA Administrator Visited Cancer-Causing Air Pollution Hot Spots Highlighted by ProPublica and Promised Reforms”

- EPA | “Full EPA Statement on Addressing Cumulative Cancer Risk”

[MUSIC: Sam Gendel and Sam Wilkes, “Boa” on Music for Saxofone and Bass Guitar, by Sam Gendel and Sam Wilkes, Leaving Records]

Fishing for Data on Chemical Runoff

Galveston Bay, in the western Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Adam Reeder, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Houston, Texas is one of the cancer hotspots ProPublica identified in its analysis of compounding chemical exposures. Houston is a hub for the US petrochemical industry and just downstream is Galveston Bay, an important fishery for the region. And scientists are trying to learn how industrial runoff might be affecting marine life there. Katie Watkins is a reporter with Houston Public Media and has the story.

WATKINS: I meet Sepp Haukubo, with the Environmental Defense Fund, and our captain LG Boyd at a dock in Texas City at the crack of dawn. We set off into the bay as the sun rises, and we can see Houston's industrial complex in the background. The two men set up their fishing equipment and Haukubo explains what they're looking for.

HAUKUBO: We have caught a lot of trout, so we're trying to get a few more red fish, some black drum. Ten's probably a good number total.

WATKINS: We won't be eating these fish. Instead, they'll be sent to a lab at Texas A&M University, where they'll be tested for the presence of certain chemicals and metals that are associated with the petrochemical industry.

HAUKUBO: So we will at least know that it didn't come from, you know, runoff from somebody's yard, or from you know, city streets--that it really did come from a group of facilities.

WATKINS: By sampling the fish, the researchers hope to understand what toxic compounds are getting into the bay during flood events and how they're building up over time.

Fish, like this speckled trout in a Seabrook, Texas market, can provide an indicator of pollution levels in water. (Photo: Patrick Feller, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HAUKUBO: You know, I eat plenty of seafood out of Galveston Bay, I eat oysters, I eat the fish I catch but that's exactly one of the reasons that we're conducting this study is so that we can get a better idea of what are some of the health risks, but also what are some of the risks to the ecosystem, right?

WATKINS: The state issues, warnings if fish aren't safe to eat and state and federal organizations have tracked similar data. This research builds on that.

CISNEROS: So we would be able to tie current data with historical data and kind of come up with new trends to track how things have changed over time.

WATKINS: That's Charlotte Cisneros with the Galveston Bay Foundation, which is also involved. She says because these fish are higher up in the food chain, they're good gauges of what chemicals are accumulating in the ecosystem.

CISNEROS: They're just kind of overall good indicators of health in the area.

Katie Watkins: Alina Craft, with the Environmental Defense Fund, says sampling the fish is just one part of the research. The chemicals that show up can be used to help identify which industrial facilities they may be coming from.

CRAFT: We're trying to understand more about, okay, well, where would these compounds have come from in terms of the industrial facility? And so really trying to understand what are the facilities that may be at greatest risk based on where they're located based on the compounds that they manage or use in their operations and so forth.

WATKINS: As the final step, they'll propose nature-based solutions that could help mitigate the pollution, things like oyster beds and green spaces that slow the flow of runoff. She says as climate change is making hurricane stronger and wetter these solutions are all the more urgent. Back on the fishing boat, we aren't having much luck. Most of the fish are either too small or the wrong kind. [WATER SPLASHING] So too short again?

HAUKUBO: Too short [LAUGH]

WATKINS: Boyd and Haukubo cast and reel, again and again until...

BOYD: There we go! Beauty now where the science starts.

Katie Watkins: It's a 20 and a half inch black drum named for the drumming noise it makes. [BLACK DRUM SOUND] Next Haukubo puts it in a Ziploc bag and into a cooler. He writes down the time, location, water temperature and other data points. By the end of the day, they had caught nine fish to be transported to the lab for testing, where they'll offer insights into the pollution in our bay. For news 88-7 in depth. I'm Katie Watkins.

DOERING: That’s environmental reporter Katie Watkins. Her story comes to us courtesy of Houston Public Media.

Related link:

Houston Public Media | “Galveston Bay Researchers Are Fishing For Data About Chemical Runoff — Literally”

[MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, “It’s Easy to Remember” on Ballads, by John Coltrane, Impulse Records/Universal/MCA Records]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on living on Earth, please consider signing up for our newsletter. You'll never miss a show and you'll have special access to show highlights notes from our staff, and advanced information about upcoming live virtual events. Some of my favorites have featured reflections from our fantastic and hardworking interns. The living on Earth newsletter is sent to your inbox weekly. Don't miss out subscribe at the living on Earth website loe.org. That's loe.org. By the way, you'll also find photos, links to more information and a full transcript of every single show there. For even more LOE, follow us on Instagram. We're at living on Earth radio. We tweet from at living on Earth, and our Facebook page is living on Earth. And we'd love to hear from you. You can write to us anytime at comments@loe.org That's comments at loe.org.

[MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, “It’s Easy to Remember” on Ballads, by John Coltrane, Impulse Records/Universal/MCA Records]

DOERING: Coming up – Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, a Buddhist approach to addressing the climate crisis. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay Tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Coltrane Quartet, “It’s Easy to Remember” on Ballads, by John Coltrane, Impulse Records/Universal/MCA Records]

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet is one of over 130 books written by Thich Nhat Hanh. (Image: courtesy of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Zen Buddhism encourages mindfulness and meditation as ways to embrace life and its challenges, including one of the thorniest challenges of all, the climate crisis. In the 2021 book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, Buddhist Zen master and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh says being in the present moment, waking up to our suffering, and acting with compassion can ripple out beyond ourselves and lead to better care of this planet we call home. Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet was edited by Sister True Dedication, a monastic Dharma teacher and Buddhist nun who lives in the Plum Village community Thich Nhat Hanh founded in France. She and his other students call him “Thay” which is Vietnamese for “Teacher”. I recently talked with Sister True Dedication and she began by explaining how we got into our current pattern of exploiting the earth.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: It is our ideas of happiness that have led us into this current situation. So we think happiness lies in consuming. We think happiness lives in striving and competing and satisfying our craving in whatever way and having these extremely resource rich experiences. But in the essence of our Zen Buddhist teachings, we know that this beautiful earth, this extraordinary planet, already gives us so many conditions for happiness. And so there's a radical kind of message in our approach to simplicity. Which is, if we give ourselves a chance to cultivate true presence, to generate what we would call an energy of mindfulness, we realize that we don't need all those things to be happy. We don't need a second car, we don't need a bigger house, we don't need more vacations. We just need to change the way we look and experience things and discover the happiness that is already there for us. And on a planetary scale this is one of the core insights that as a species, humanity, we would need to wake up to, in order to be able to change our way of living. Because our current economy, our current lifestyles, are leading, and we know this very clearly, our lifestyles are leading to the destruction of our beautiful planet, of the natural world. And there's nothing to be afraid of in this kind of simplicity, that takes us in another direction away from the mindless consuming.

Members of the Plum Village monastic community in France, where Sister True Dedication lives, plant trees in late 2021. The Plum Village brothers and sisters strive to practice the art of living in harmony with one another and with the Earth. (Photo: Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism)

DOERING: So this book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, is really calling for a radical shift in the way that we understand ourselves in relation to everything else. You call this an "insight of interbeing." Could you explain this and tell us why is it important to our efforts to address climate change and other environmental crises?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So the word "interbeing" is a word that our teacher created, it's not a word that you can actually find in the dictionary yet. And it really means that we can understand that we inter-are, we are profoundly interconnected with everyone and everything around us, including the living world, including the natural world. What this means in the light of our planet is that, in fact, some of the reasons and the ways of thinking and seeing that got us into our current problem, are because we see the Earth as something outside of us, something separate, even something inert that is there for us to exploit, to be master of, that is there somehow for us to use. But with the insight of interbeing in the Buddhist teaching, we see that we are part of the Earth, we are profoundly interconnected with the Earth. And this is fully in line with science and the teachings on evolution. For example, a tree is not just there to provide us with fruit. It is not just there to provide us with wood to make furniture or build our homes. Like, our trees are intimately part of who we have become as a human species. Their oxygen is our in-breath, their out-breath is our in-breath. And to see the life in the tree, the wisdom in the tree, and to not think that we are entirely separate from one another. And we know that there's going to be a radical difference to the planet, if all the trees weren't here, just as there would be a radical difference if all the humans weren't here! So it's to really look deeply using both the eyes of science, but also, like, the eyes of what we might call a more spiritual dimension.

DOERING: You know, one of the key ideas here in the book is about the importance of maintaining ourselves and caring for our own selves, not succumbing to burnout, which I think is something that a lot of people can relate to now in our modern world. Could you tell me about how this, you know, mindfulness and interbeing can really help with that, can really set us up for actually doing the work that we want to do and caring for the Earth in a way that we aspire to?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Hmm. That's an excellent question. Yeah, I think if we want to care for our environment, we have to care for the environmentalist as well. It's like, the two are deeply interconnected. The energy of mindfulness helps us be present in our day, so that we're not kind of lost and swept away and overwhelmed. And that's when we start going beyond our limits, when we get caught up in things and we're not really being, being able to be fully present for what is going on. And so we'd say that in the practice of mindfulness, we learn to be able to handle our strong emotions, our painful feelings, and we also learn to kind of maximize, or optimize, our feelings of well being and happiness. So we're doing these two things at the same time: nourishing joy and happiness, and handling pain and suffering, if you like. In a really granular way, what this means is that when we hear bad news relating to the planet -- we may have watched something on the screen, we may have heard a news bulletin, and a feeling comes up. And that feeling may be sadness, it may be grief and despair. Or it may be anger and resentment, perhaps, especially at our political leadership at this point. So those are real feelings. And in the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, we speak about the power of aspiration and intention. And it's possible to metabolize some of our painful feelings with mindfulness, with concentration and insight, and transform them into a source of energy to take action, and to take radical action, which is what is needed right now.

WATCH: Sister True Dedication’s TED talk, “3 questions to build resilience – and change the world”

DOERING: You mentioned anger, and these emotions that come up with the climate crisis. And it's true, I mean, just a few people and companies have emitted far more greenhouse gases than most of the people in the world. And they've known, largely, the problems with what they're doing. And yet, they're also not the ones that are the most vulnerable to climate impacts. So this is just a huge injustice. And it makes a lot of climate activists very angry. So to what extent can anger like that be constructive? Or what do Zen teachings have to say about, like, how to use it, how to "metabolize" it, like you said?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So Thay, our teacher, once said that a little bit of indignation can be okay, can be healthy enough to get us off the cushion, to engage us into action. But, he said, the energy of anger burns us up, it really burns us up. And for me, we had a very powerful experience in Scotland with some events around COP26. There was a protest at this event against a new oil speculation, oil searching in the North Sea. And there was a very angry young activist and the CEO of Shell had to listen to her directly. And at the time, everyone thought it was terrible and dramatic. But the monks and nuns, those of us there, we thought this was a very healthy conversation. One side had to listen to the other side, and how powerful that this Shell CEO had a chance to hear the voice of the youth and their desperation and their suffering. And anger is there for a reason, anger is there because people are not being heard. So for me, it was very powerful to witness this protest. And the incredible news is that, you know, six weeks later, Shell pulled out of that exact oil field, the Cambo oil field in the North Sea. And for me, my response wasn't a sense of... my response was gratitude to him, and that he woke up and he realized, and was able to oversee that decision to pull out of that oilfield. And we should all be feeling shock and outrage in many ways. But the energy which then gets us onto our streets, or takes us to the voting booth, that energy, if it's an energy of love and positive action, that will sustain us so much more than the energy of anger.

Plum Village brothers and sisters pick end-of-season apples at a nearby orchard (Photo: Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism)

DOERING: Yeah, and you, and you mentioned being grateful to the Shell CEO. And it seems like he must have been listening to that activist who was very angry. And like you said, it's a conversation, it's a dialogue. If two sides can come together and respectfully engage, there should be a positive outcome.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Yeah, in Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, we also explore this question of dialogue, and brave dialogue. When we can meet, human to human, across all the kinds of polarization that we have in our societies, I believe that real transformation is possible. It's when we demonize each other and we demonize our actions that we really are going down the kind of wrong path as a species, because we will need to collaborate, we do need to listen to one another. We do need to find collective insight to get ourselves through this fiendishly difficult problem of really addressing climate change and the destruction of nature in all these aspects. And so what was powerful in the dialogue in Scotland was it didn't necessarily look like the CEO was listening at that time. Because sometimes, listening takes longer for the insight to settle and for courage to manifest, the courage of right action. To offer that gift of listening is I think one of the greatest gifts we can offer one another and that the practice of mindfulness allows us to give. And I think that has huge potential in the climate movement in general. And that's what we've seen in the conferences where we've participated and brought the practices from the book into these conferences. It's the listening that people are most eager to learn.

Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh passed away on January 22, 2022 at the age of 95 after this interview was broadcast. (Photo: Courtesy of Plum Village Unified Buddhist Church)

DOERING: Mmm. And, in fact, I was really interested to read in this book that Christiana Figueres, the architect of the Paris Climate Agreement, is a student of Thay. So how did his teachings help shape the success of Paris?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So Christiana has shared with us that it was her own kind of spiritual strength that she drew from Thay's teachings and from various mindfulness practices that gave her the sort of personal strength and faith to be able to carry through all the negotiations leading up to the agreement. But specifically, Christiana highlighted the practice of deep listening. And she found a way through her own embodiment of this practice to be able to show up, and she speaks about meeting both coal investors and island nations that are really in danger. And being able to come with a truly open heart and to ask truly open questions, and to have that sense of inner courage and openness for whatever they wanted to say. To really allow people to find their own words to describe their suffering, their struggle as a nation or as a corporate CEO. It's not that corporate CEOs are without their struggles too, and how can they name and articulate them, and that's their struggles that are driving their unmindful action, right? It's the irony, this is this weird irony in Buddhist teachings, it's exactly by getting in touch with our suffering that we can find the way out of it. It's exactly by waking up to the suffering, naming it, really getting down to what it is, what is driving those oil companies to be so stubborn, about continuing to do what they do, what is it? And in those human beings at the top of those companies, what is it that they are still caught in, that they haven't yet discovered? And only when we can identify and really name it, and be with them, as they realize this about themselves, then right away, we will wake up to the way out and to new solutions. So it's by leaning into these dark places that we can really see the light to kind of find the way out.

DOERING: So for someone who's listening, who is yearning to get in touch with this sense of interbeing, and wants that connection, wants to be able to sort of fuel their care for the planet with mindfulness, and reconnect. What would you recommend in terms of going outside and connecting with nature? And what should the mindset be of someone who wants to do that? Is there a specific question or thought that they should bring to mind or just simply go out and be? What would you recommend?

Sister True Dedication provides commentary throughout the book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet.” (Photo: Plum Village)

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Hmm. So the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet opens with a beautiful invitation to listen to the Earth. And a very simple way to know whether we're in the present moment or not, is whether we're with our five senses. So with what we can hear: if you can hear the birdsong, you're in the present moment. With what we can smell: if you can smell the leaves on the forest floor, you're in the present moment. If you can feel the breeze on your face, you're in the present moment, or taste the salt on your tongues, if you're by the sea. So, being with our senses, we're in the present moment already. And to take a moment to really pause. And I think some people say, Oh, my mind's so distracted, my mind is thinking of this, it's thinking of that; my phone's vibrating in my pocket. So maybe you really need to turn off all your notifications before you go on such a walk! And the trick with mindfulness is, the more we allow our senses to be fascinated by the present moment, everything we can see, hear, smell, or even taste or touch -- the bark of a tree, perhaps -- the more we're in touch with these senses, we've got no time to think. You're, the thinking won't happen. So then just keep coming back to all of these sense impressions as we are being with nature, and just really having a moment to be with the vitality of life. So the, the challenge is to open up our curiosity, and that is already a huge source of nourishment, and that is already, we're, we're living the truth of our interbeing with the Earth. It's not an idea. It's not a notion. It's an experience that each one of us can then have.

DOERING: Sister True Dedication is editor of the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet by Thich Nhat Hanh.

Related links:

- Find the book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn about the Plum Village community founded by Thich Nhat Hanh

- About Sister True Dedication

- NowThis News | WATCH: “Young Activist Confronts Shell CEO About Climate Record”

- The Guardian | “Shell Pulls Out of the Cambo Oilfield Project”

[MUSIC: Benedetti & Svoboda, “Sueno” on Journey to the Heart III: Music for Healing, by Benedetti & Svoboda, Coroco Sounds]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth