February 11, 2022

Air Date: February 11, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Congress and Climate Action

View the page for this story

To pay for clean energy and climate resiliency investments needed to complement the infrastructure law passed last year, a group of House Democrats is calling for President Biden to push a revised budget reconciliation bill that can get all Senate Democrats on board, now that the omnibus package known as “Build Back Better” has been scuttled. Democratic Congresswoman Katie Porter of California joins Host Steve Curwood to explain as much as $1 trillion in Congressional budget climate action is needed over the next ten years to avert more climate disasters. (12:14)

In Honor of Black History Month: Harriet Tubman and the Barred Owl

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

As a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman led some 70 people out of bondage, through woods and wetlands she knew well. Host Steve Curwood describes how Ms. Tubman used local bird calls including that of the Barred Owl to signal an all-clear to freedom seekers without attracting the attentions of slave catchers. (01:57)

Forest-Friendly Chocolate and More

View the page for this story

When someone takes a bite of a hamburger or tofu or has a cup of coffee or hot cocoa, it’s hard to know if those foods added to the destruction of tropical forests that are so key for biodiversity and climate stability. So as part of the European Union’s Green New Deal the EU is moving to ban the importation of of a half-dozen agricultural products from any newly deforested areas. Anke Schulmeister, a Senior Forest Policy Officer for the World Wildlife Fund, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss this pending legislation. (07:05)

Green Walls For Life, Air and Energy

View the page for this story

Green walls, which are living walls of plants installed on the side of buildings, can help clean the air, improve energy efficiency, and support biodiversity. Matthew Fox, a researcher at the University of Plymouth, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how green walls work, their potential applications, and the benefits they offer for people and pollinators. (08:16)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News Weekend Editor and columnist Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb for their weekly trip beyond the headlines. First up, the pair discuss the threat to plants who rely on endangered animals to disperse their seeds throughout their habitat. Then, they investigate how Q-Anon forced the National Butterfly Center to close to the public. Finally, the two look through the history books at a famous New York City urban legend. (05:05)

Beavers Move Into the Arctic

View the page for this story

The Arctic is warming roughly twice as fast as much of the globe and some species are already moving toward the poles in search of new habitat. And as beavers move north into the Arctic these big rodents known as “ecosystem engineers” are bringing big changes to the landscape. Ben Goldfarb is the author of Eager: the Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter and joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss the concerns and benefits of beavers in the Arctic. (08:40)

Sounds of Winter

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

Listen closely. The frigid months of winter have a sound uniquely their own. As commentator Sy Montgomery points out, the cold and gray season’s bareness and rigidity help make its sounds vibrant. (03:46)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220211 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Matthew Fox, Ben Goldfarb, Katie Porter, Anke Schulmeister

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Sy Montgomery

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Leading Congressional Democrats say it’s false economics to go low and slow with federal budget options for climate action.

PORTER: The longer we delay the more difficult it is to solve our climate crisis, the more expensive it is to solve our climate crisis and the fewer options we have so we talk about comparing the costs of addressing climate change we have to measure that against the cost of inaction.

CURWOOD: Also, with a hotter planet beavers are moving into the Arctic, raising concerns for some about changing habitat and melting permafrost.

GOLDFARB: Are animals that move north because of our actions in warming the climate, are those invasive species? I would argue not. They’re animals that are just resourcefully adapting to conditions that we’ve created for them.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Congress and Climate Action

The orange California sky resulting from wildfires in Oakland in 2020. (Photo: J Healey on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

To pay for more climate action beyond that in the infrastructure law that already passed last year President Biden and the House Democrats tried to roll it into a broad $1.5 trillion package for budget reconciliation called Build Back Better to avoid filibuster in the Senate. But with a razor thin majority every Senate Democrat needed to sign on, and despite months of wrangling, they didn’t. So now a group of 23 House Democrats is calling for President Biden to push climate-centric measures in a revised budget reconciliation bill that can get all Senate Democrats on board. Congresswoman Katie Porter of California is part of this group. She is also Deputy Chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, and joins me now from Irvine, CA. Congresswoman Porter, welcome to Living on Earth!

PORTER: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So let's cut right to the chase here. How much of the half a trillion dollars that was originally part of the Build Back Better bill, or budget reconciliation, depending on whatever you want to call it -- How much of that should Congress spend on climate right now? And what are the costs of not making those investments?

PORTER: We definitely need to spend what we had allocated in the original Build Back Better Act. And I'm hopeful that we will see climate be prioritized in whatever budget reconciliation bill we move forward with. We know we're starting over, we have to have new conversations and new negotiations, but nothing about the climate problem has gone away. So nothing about climate solutions needs to change. And if anything, the point I make over and over again, is the longer we delay, the more difficult it is to solve our climate crisis, the more expensive it becomes to solve our climate crisis. And the fewer options we have to solve our climate crisis. So when we talk about comparing the costs of addressing climate change, we have to measure that against the costs of inaction.

CURWOOD: So give us some of those numbers, please.

PORTER: Well, let me give you one example: weather and climate-related disasters cost taxpayers $145 billion, just in 2021, just last year. $145 billion, and that money basically is gone. It goes into one-time repairs, it goes into fixing things up; it's disaster response. If we instead invested that money in preventing disasters, in coastal resilience, for example, and wildfire prevention, and things like that we could actually not only save that money, but we'd be spending it in a way that is creating jobs, that is keeping first responders out of harm's way. It's really, really important to understand, climate change is happening, whether Congress does something about it or not. And it is costing taxpayers. So the fiscally responsible thing to do is to pass science based policy that will effectively address climate change.

CURWOOD: This has hit you personally, I gather there have been some wildfires out there in California. How did that affect you?

PORTER: Yes, so we had wildfires here, two of them in the last year or two alone. And during the pandemic in particular, it was very difficult, because people were in their homes, they weren't able to necessarily travel or leave. Evacuations were more difficult, but the air quality was so terrible that they were unable to have kids come into school, they had to cancel recesses. And so that has real health costs to people in terms of triggering asthma, triggering respiratory disease. We also had an oil leak off the coast of Huntington Beach here in Orange County. And that's another area where it is expensive to keep subsidizing the fossil fuel industry, which very often pollutes and leaves taxpayers to foot the bill. So that is another big part of what was in the Build Back Better Act, including my legislation to update the rental and royalty rate. Because today taxpayers are spending a lot to subsidize the fossil fuel industry, rather than subsidizing or investing in, I should say, forward-looking clean energy job creation.

The climate policies that are in play in Congressional negotiations include an increase in the minimum onshore royalty rate for federal oil and gas leasing from 12.5% to 20%. (Photo: WildEarth Guardians, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent are you expecting to have an element of the new budget reconciliation bill that considers climate that would reduce, I dare not say eliminate, subsidies for the fossil fuel industry? I mean, that's a tough hill to climb, given the power that industry has there in Congress.

PORTER: Well, the good news is we have seen major changes in people being willing to really dig in and look at, what is the fossil fuel industry doing? And I'll just offer a couple I think examples that should, should make us feel like we are making progress on this, despite their incredible lobbying power, which you correctly note. The Oversight and Reform Committee that I serve on had the Big Oil CEOs come in for a hearing this last year. And that was the first time that Big Oil has ever testified before Congress. The fact that we're having those hearings on what has Big Oil's said about climate pledges versus what are they actually doing, on issues like greenwashing, that's very encouraging. The other thing I'll note is the effort to make sure that when we lease public land, or public water, for drilling, or for mining that we are getting a fair return is actually bipartisan in the Senate. It's Jacky Rosen, a Democrat from Nevada, and Chuck Grassley, a Republican from Iowa. You often hear about tax fairness as an important issue from both sides of the aisle. This is something that we should be able to agree on.

CURWOOD: I'm going to come back to the proposed legislation in a moment, but let's go further on the question of using public lands. One of the things that President Biden's administration did right around the time of COP26 was go ahead with authority to lease 80 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico. And I think ExxonMobil and Chevron snapped up nearly 2 million acres of that. I mean, the White House says, Well, there's a court decision that forced us to do this. But it doesn't exactly sound like the President's pledge to stop using public lands to increase climate risk.

PORTER: Well, I think there are a couple different things going on. One is that it was positive that President Biden put a pause in place. And as you note, there was litigation that forced that planned sale to go on. But the report that the administration put out on the use of public lands for oil drilling contains some really important fact finding, and really makes the case for why we need to get a fair return. And so I have a lot of confidence in Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland, my former Congressional colleague, to take positive steps. But there are real issues with regard to some of the agencies, including the Bureau of Land Management and others, who often have had a very longstanding and frankly, quite close relationship with extractive industries, whether that's logging, or fossil fuel. So I do think we need to rethink this, as President Biden talks about preserving 30% of our public land by 2030. What we need to have is forward-looking energy policy that is honest about the reality of the climate crisis.

Congresswoman Katie Porter (D-CA) says funding for more electric school buses is an important part of federal climate legislation that should be included in the upcoming budget reconciliation bill. (Photo: UniversityRailroad, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: What are the elements that need to be in this rewritten budget resolution, the child of Build Back Better, we might call it, in terms of the climate? What are the top priorities?

PORTER: Well, one of the things we have to do is remember that the Jobs and Infrastructure bill, the bipartisan one that President Biden signed that is law, was never designed to exist on its own. It was always to be paired with the climate activity in Build Back Better. And that is because transportation is our biggest source of emissions for fossil fuel. So we were always intending, for example, even as we repair roads and bridges in the infrastructure bill, to pair that with investments in Build Back Better in things like electric vehicles, you know, electric school buses, with things like carbon recapture. And when we talk about job creation, infrastructure jobs are real, and they are happening around the country because of that bipartisan infrastructure bill. But those are jobs for one sector and one segment; they're often, you know, they exist for a certain period of time, and then the bridge is built or the dam is repaired. Clean and green energy jobs are jobs that can sustain our economy for the next 100 years.

CURWOOD: Now Congresswoman, is there a number that you associate that would take care of getting those things funded that need to be done in tandem with the already enacted infrastructure bill? How much money are we talking about here, do you think?

PORTER: Well, I would say that, at minimum, we ought to be thinking about $500 billion dollars. The overall Build Back Better Act was $1.5 trillion, I think we want no less than a

third of that to be related to climate. But I would say, you know, somewhere upwards of $500 billion, $750 billion. If it's done right, and we are making long-term plans, I think we could even do a trillion on green energy and climate and, and really come out ahead in our economy going forward. People also have to remember, that is over 10 years. So it is important that we do not do something that is one year spending, then not doing it, because the cost of turning on these investments, and then stopping them is incredibly expensive. Science doesn't work that way. We want to be asking ourselves, How much do we want to be spending in year 10? And I think that pushes us toward having the fiscally responsible thing be a bigger number that's closer to a trillion dollars overall.

Representative Katie Porter (D-CA) poses in front of the U.S. Capitol building for her official photo for the U.S. House of Representatives. (Photo: U.S. House of Representatives)

CURWOOD: By the way, how do the climate initiatives that were originally outlined in the Build Back Better bill that you and your colleagues passed through the House, how does that advance environmental justice?

PORTER: Yes, so part of this is a very explicit commitment by President Biden, to make sure that resources devoted to investing in clean energy and invested in environmental remediation are going to the communities that were most affected. And I think this has a couple different parts. One of the things that we need to do is recognize that some of the most important environmental activists we have in our country right now are black, indigenous and people of color because they are living closest, in so many cases, to the pollution. And they have firsthand been experiencing both the health harms, the community harms, the environmental degradation. And so we want to make sure that those are the communities that are also leading the way and being powerful voices in thinking about how to address and remediate the situation. This is also a huge opportunity to create jobs because the people who often work in the fossil fuel industry, many of them are lower wage workers. So when we talk about a just transition, how are we going to train and locate the training opportunities, the apprenticeships, the pathways to career success in the communities that are at risk of losing jobs as we make that, that transition.

CURWOOD: I'd like you to drill down on the health implications of this climate legislation. Folks at the Harvard School for Public Health say that about 300,000 Americans die each year from breathing air that has gone through internal combustion engines and other uses of fossil fuels. So to what extent would this legislation cut that death rate? Yeah,

PORTER: Yeah, and by the way, those deaths are often through chronic disease. And so they're not only painful and difficult and loss of lives, but there's often years of treatment, of medication; it's the loss of life, it's also the amount of resources in our healthcare system that we're putting into caring for sick people rather than investing in from a public health standpoint, and from a healthcare standpoint, in keeping people healthy. So, over time, can we bring that number down from 300,000 to 200,000? Absolutely. Is it going to go to zero? No. But we need to be showing the American people the pathway to making progress. And it's not going to happen if we continue to allow big oil companies to write our energy policy.

CURWOOD: Congresswoman Katie Porter represents California in Orange County, I think it's the 45th District. She's also Deputy Chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. Congresswoman, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PORTER: Thank you for the conversation.

Related links:

- House Democrats’ Letter on Climate to President Biden

- Rep. Katie Porter Breaks Down the Build Back Better Act

- Energy and the Environment page on Katie Porter's website

- Whitehouse.gov: The Build Back Better Framework

- Center for Climate and Energy Solutions: Build Back Better for Climate and Energy

[MUSIC: Bill Tapia, “Lady Be Good” on Duke of Uke, by George and Ira Gershwin,

MOOnROOmRECORDs]

In Honor of Black History Month: Harriet Tubman and the Barred Owl

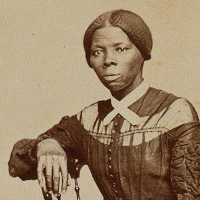

Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman in the late 1860s. (Photo: Benjamin F. Powelson, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

[BARRED OWL CALL]

CURWOOD: Born in 1822 or so, Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery near Cambridge on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1849 to the free state of Pennsylvania, just a hundred miles way. She returned some 13 times to guide another 70 or so people out of bondage. Her knowledge of the woods and wetlands near Chesapeake Bay and its creatures was crucial to her success.

Under cover of night, Harriet Tubman would mimic the hoot of a Barred Owl to signal an all-clear to freedom seekers. (Photo: Travis Warren, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[NATURAL SOUNDS OF THE REGION]

CURWOOD: Famously she used bird calls to alert freedom seekers if it was safe or not to proceed. To signal it was ok to slip away and join her, she would hoot like a Barred Owl.

[BARRED OWLCALL]

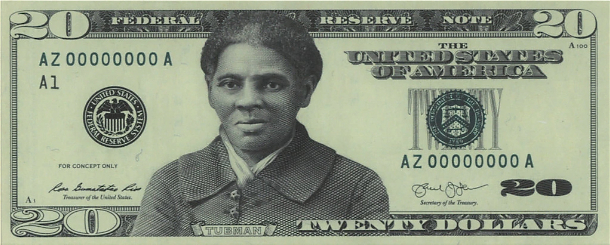

CURWOOD: Barred Owls like to roost in big trees near the water and typically hunt at night, so a person imitating one could blend in with nighttime sounds without raising suspicion. The cover of night and the light of the North Star combined to help Ms. Tubman guide her passengers on the underground railroad, and she fed and cared for them using her knowledge about medicinal and edible plants. Later during the Civil War, in the only such action by a woman that’s recorded, Harriet Tubman led a Union raid up the Combahee River in South Carolina that liberated some 750 slaves. She was also an activist for women’s voting rights and lived to 90 years of age. These days the Biden Administration is working to put Harriet Tubman on the front of the 20 dollar bill and perhaps move a statue of Andrew Jackson to the back.

[BARRED OWL CALL]

CURWOOD: And maybe the Treasury Department should also consider having a barred owl join the Federal Reserve eagle.

Official $20 bill prototype featuring Harriet Tubman, prepared by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 2016. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Related links:

- Audubon | “Harriet Tubman, an Unsung Naturalist, Used Owl Calls as a Signal on the Underground Railroad”

- National Park Service article about the North Star to Freedom

[MUSIC: “Follow the Drinking Gourd” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qpW9QWi2Dbk]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The potential for living walls to improve energy efficiency and clean the air. Keep listening to on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana.

Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “The Train of Thought” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Forest-Friendly Chocolate and More

An aerial shot shows the contrast between forest and agricultural landscapes near Rio Branco, Acre, Brazil. (Photo: Kate Evans, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

When someone takes a bite of a hamburger or tofu or has a cup of coffee or chocolate bar it’s hard to know if those foods added to the destruction of tropical forests that are so key for biodiversity and climate stability. So as part of the European Union’s Green New Deal the EU is moving to ban the importation of certain agricultural products from any newly deforested areas. And they are starting with soy, beef, palm oil, wood, cocoa and coffee. The EU laws would compel purveyors to prove their products didn’t come from any newly deforested land. The proposed laws are projected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by some 32 million tons a year and help the EU meet its goal of net zero emissions by 2050. It requires final approval by the European Parliament as well as each of the 27 EU member states. Joining us now from Belgium, which among other things is famous for its chocolate, is Anke Schulmeister a Senior Forest Policy Officer for the World Wildlife Fund. Welcome to Living on Earth Anke!

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, welcome. And thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about chocolate for a moment. So right there in Belgium making amazing chocolate, which then gets sold with a nice Belgian label on it. How would this be enforced? How will people be able to understand that the cocoa that was used to make this chocolate came, in fact, from a place that's not being deforested, at least in contravention of this proposed set of regulations?

SCHULMEISTER: Yeah, I think this is a very good question. I think what this law is trying to do is that there is no choice for a consumer on whether the product is made with deforestation or not, it's just simply you're making sure that no matter which chocolate you buy, it is going to be free from deforestation. And to achieve that, there are measures in this legislation proposed that will ask a company to check down the whole supply chain. So, all of the people they buy from, you know, where do they buy it from knowing where the people are, and knowing in the end, where the origin of that is, and being assured that in that origin--so first the country and then the region, and then maybe even further down-- there has been no environmental impact. So negative environmental impact, neither human rights violation taking place. So, they would need to follow the laws of the country of origin. But also, in addition, make sure that the EU rules are followed. Because just to give you an example, for example, in Brazil, deforestation is still legal in certain aspects. And that means that you know, about 88 million hectares of forest could still be deforested. And what the EU at the moment is proposing is to say, even if the Brazilian law allows that, we in the EU do not want to buy this. So you know, no matter whether it's allowed, we will not accept any solid coming from these areas.

Some Europeans share concerns about deforestation. ????????????

— European Commission ???????? (@EU_Commission) November 17, 2021

They call for Europe's reforestation and for saving our planet's lungs to slow down global carbon pollution.

Do you agree?

????Make your voice heard here: https://t.co/8HDeiii39R#TheFutureisYours pic.twitter.com/j50e9tIijE

CURWOOD: So beef is part of this, which of course, at the end of the day means leather. So let's say an American shoemaker, who has a contract with somebody in China is now selling that label in the European Union, once this rule goes into effect, what kind of challenge would they would they face?

SCHULMEISTER: This is a very good question, because that goes really much into the depth of it. So normally, what the commission has proposed is that you would need to know where it was produced no matter whether it came by China, or else. So if this American shoemaker would like to actually sell in Europe, he would need to get from his Chinese supplier information that tells him where he actually bought the leather. And then in the end where the cow was fed that produced that leather?

CURWOOD: Sounds very complicated.

SCHULMEISTER: Yes and no. Because let's put it like this: we're asking something rather simple in stating, is there still land where there's forest or has this forest been converted to something else? And for this, there's a lot of satellite data these days available. So you know, it's very clear, very regularly updated. What is making it a bit more complicated is that there is a need for more transparency about your supply chains. So you need to be more open to where did I actually buy it from? And whom did I buy it from? Which we do think is a benefit. Because it makes it more transparent and more assuring for the consumer.

CURWOOD: So of course, at the end of the day, this is aimed at protecting our climate. What are the numbers? What kind of reductions in emissions, carbon emissions, do you think these rules, this legislation, will create?

SCHULMEISTER: So the European Commission, its impact assessment estimated that if there is no intervention, so if there's no law, there will still be about 248,000 hectares a year of deforestation, and about 110 million tons of C02 emitted until 2030 per year. And it's quite logic, because what are we talking about? We're talking about cutting down a forest and would make it into agricultural land. Which means that forests are not storing carbon anymore. The trees are potentially burned, you know, so it's quite an accumulation of CO2 that could be coming out of that.

Fragile Cerrado grasslands and the Pantanal wetlands, both under threat from soy and beef exploitation, are not included in from a European Union draft anti-deforestation law. (Photo: Julio Phan, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, you're a forest policy expert. In your opinion, what is missing from this proposed set of rules and legislation by the European Commission?

SCHULMEISTER: So let me first say that we do think this is a very good start. I mean, we've been fighting for this, and we've been fighting hard for this for the last 10 years. So we think that European Commission is on the right track. But you know, what our plea would be now to the European member states and the parliament is that, you know, to close some of the gaps which we see. One is that for example, other ecosystems--savannas or grasslands--are not included from the beginning. We call actually savannas the inverted forests, meaning that their roots store nearly as much carbon as actually forests do, you know. On the landscape that they are they have such a dense root system, you know, that they really store a lot of carbon in there and that is then if it's converted to agricultural land lost. So there is going to be a review within two years time after the law enters into force to see whether they should be included. But it looks a bit like you know, if you would have a beautiful landscape photograph on your wall, and you have to cut out you know, about five square centimeters of that photo and there's this blank spot this is where the savannas or others were. So you still have the forest, but the rest is missing. And I think, you know, we think this is an omission because we are importing a lot from those areas as well. That's the one thing. It is not very strong on human rights violations or actually ensuring that there are no human rights violations. So this needs to be looked into. And though we do really appreciate that it is targeting companies and sets some strict rules for them, it is not addressing the finance sector. And EMA, that's also missing a bit if we have the companies who are doing the works in those regions, but not those banks or finance sectors, which are funding those companies. And I think we think this also needs to be addressed. And what for us is important is that this law applies the same to all companies so that we do not make a differentiation between sourcing from a high-risk region--so where there's a high risk of deforestation--or a so-called low risk region. We do think that you know, every company should be treated the same. And even if a company is sourcing from a high-risk region, there can be companies who have a good traceability and a good transparency. So they should all have the same rules and there should be a level playing field for them all.

CURWOOD: Okay, Schulmeister is the senior forest policy officer for WWF. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SCHULMEISTER: Well, thank you very much for having me and have a great day.

Related links:

- European Commission: Questions and Answers on new rules for deforestation-free products

- The Guardian: EU aims to curb deforestation with beef and coffee import ban

[MUSIC: Time For Three, “Everything’ll Be Alright” on Time For Three, by J.

Radin/arr.Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics]

Green Walls For Life, Air and Energy

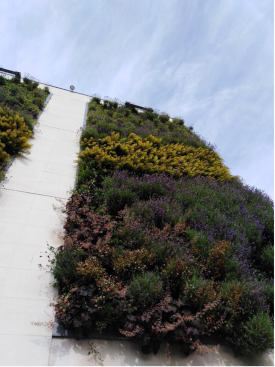

The Living Walls from University of Plymouth (Photo: Paul Lunt, University of Plymouth)

BASCOMB: Researchers at the University of Plymouth in the UK have been looking into the many benefits of installing a living wall of plants on the side of buildings. They’ve found the green walls can work like insulation to dramatically reduce heat loss and improve energy efficiency. And the plants, including evergreen grasses and native flowers like daisies, can filter fine particulates smaller than pm 2.5 to improve local air quality. Matthew Fox is a researcher at the University of Plymouth who studies green walls on buildings and joins me now for more. Welcome to Living on Earth!

FOX: Thank you very much, Bobby. Lovely to talk to you.

BASCOMB: So what was your basic finding in this study in terms of the benefits of green walls when it comes to you know, heat and energy savings?

FOX: Okay, so at Plymouth, we were measuring the heat flow through two pieces of construction that were identical. Apart from one section of the wall, we had an external Greenwald facade. And we use scientific equipment on both of those sections of walling to measure that flow of heat through the walling. And really interestingly, we found that by placing an external facade of green walling, we improved the heat for the thermal performance by approximately 1/3 over the original state of that wall.

BASCOMB: And so are the plants acting as sort of like an insulation then? Is that how it works?

FOX: Yes, so we believe that the planting is acting as a slight insulator. And interestingly, we're thinking that the foliage is acting as a wind buffer against the external surface of the wall. So it's not just necessarily the the material of the green walling itself or the soil, but actually the sort of physical makeup of the external facade, and the way in which it might trap air pockets, in the same way that you'll have trapped air pockets within a polystyrene insulation, or mineral wool insulation, you're actually getting this in the planting itself.

BASCOMB: And of course, you'd have the opportunity here to plant native species and perhaps help local pollinators. Can you tell us a bit about the potential there?

FOX: Yeah, definitely. So for our green wall, we specifically looked for local native plants, rather than bringing in foreign species. And the benefit of that is that you then attract the local biodiversity, so the local insects and as you said pollinators to the plants, and some of the plants we chose, we chose specifically because of a flowering plants. So during the spring and summer months, you provide those sort of perfect opportunities for the pollinating insects and bees to kind of come in, and you're providing that kind of platform for those insects to thrive, which in the UK, I don't know how it is in the States, but our population of bees and other insects pollinating insects are dwindling. So if green walls could be encouraged, then, who knows? We could help to reverse the decline in pollinating insects.

University of Plymouth’s first green wall (Photo: Paul Lunt, University of Plymouth)

BASCOMB: It's a problem worldwide, unfortunately. So how exactly do green walls work? I mean, how do you keep the soil and the plants in place on a vertical surface?

FOX: Okay, so we're using something called a phyto textile, which is recycled plastics, that are kind of broken down into almost like a fiber. And they're kind of they're woven together into these small pockets, which you then fill up with the soil matter. And then you can plant your plants into those pockets. And they're all hung on a vertical metal system that's fixed back to the existing walls, facade. And they're all kept nice and watered by an irrigation system, the irrigation system that we've got done at Plymouth is fed by a grey water harvesting tank. So it's taking rainwater from the sky, storing it in the tank, and then we have this gravity fed irrigation system through the plants. So it's all sort of low impact watering system there.

BASCOMB: So I'm imagining, it's sort of like one of those things you put over the door to put your shoes in you know, and each little pocket withholds soil and a plant. Is that the idea?

FOX: That's exactly what it would look like, except instead of your slippers, it would be soil.

BASCOMB: What advantage, if any, is there have a green wall over a green roof, let's say, which is maybe a bit more common?

FOX: The benefit of a green wall over a green roof is that you can more easily hang the green wall off an existing building. So with a green roof, typically you need more construction work to be able to facilitate that. So when you put a green roof in, the foundations might need to be enhanced to take the loading. So the green roofs are heavier weight than a green wall facade. Also, you might need to improve the roof structure to be able to take the green roof, whereas with the green wall is just a very simple frame that will work on the outside of the building. And I think it's a much lower cost solution for retrofitting.

BASCOMB: Now, is this something that a homeowner could do on their own home? Or do you need to have you know, professionals come and install this green wall?

FOX: A homeowner could absolutely do this themselves. And we're working with researchers in Holland and Germany at the moment and looking at a system that they're creating using 3d printing to create some really innovative wall planting systems. So a slightly different greenwall facade to what we've used down at Plymouth. And this is the sort of thing that you can buy off the shelf, or will you hopefully be able to buy off the shelf in the future. And it is very straightforward to install.

Vertical garden and columbarium at the English Cemetery in Málaga, Spain. (Photo: Daniel Capilla, Wikipedia Commons)

BASCOMB: So you did this research in the UK, which gets pretty chilly. But where I'm sitting here in New England, the height today is going to be about 20 degrees or negative 6 Celsius. How appropriate is this idea of a greenwall for very cold climates?

FOX: Okay, well, you'd be surprised at how cold it gets in the UK. However, in the UK, our main concern is rain and precipitation. We are a maritime climate. And we get battered by the Atlantic weather fronts that come in. And we're primarily concerned about water and protecting from water. In a really cold climate, I think that what we've demonstrated through our research is that a green wall could help to give an extra layer of thermal buffering, so we can help to minimize the heat loss through buildings. We're going to be looking at how a green facade can benefit buildings during the summer, because you just pointed out a 20 degree high could be experienced during the winter, I've no doubt during the summer months, you have higher temperatures that we enjoy in the UK. And there's certainly research out there that suggests a green wall facade during the summer can help to cool the internal space, it can reduce the cooling demand, so reduce the need to have artificial air conditioning during the summer months. So the green wall facade could give you benefits both in the winter and in the summer. And that's certainly something we're gonna be looking at going forwards as part of our research project.

BASCOMB: What do you see as the potential social benefits of green walls? And you know, how have people responded to them so far.

FOX: We're particularly taken by the interest in green walls. The response we've had from people who live in and around these areas has been fantastic. And in the building that we were doing the research on, they have an internal green wall as well. And it's the area of the building where new people who are visitors who come to this building, they kind of gravitate towards it. It's like a magnet, it draws you towards the wall, and you want to go and touch the wall, you want to sniff the plants, and everyone comments on it. And it's always positive. People really engage with the green wall, whether it's inside or outside. And that's not you don't find that with any other building material. And perhaps we need to be looking at buildings of the future that engage people on that basis.

BASCOMB: Matthew Fox is a researcher and associate lecturer at the University of Plymouth School of Art Design and Architecture. Matthew, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

FOX: It's an absolute pleasure, Bobby, thank you very much for having me along.

Related link:

University of Plymouth | “Living Walls Can Reduce Heat Lost from Buildings by Over 30%, Study Shows”

[MUSIC: Time For Three, “Happy Day” on Time For Three, by N.Kendall/arr,Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Finding joy in the sounds of winter. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Newberger-Mazzy-Thompson, “Aunt Hagar’s Children” on The

Men They Will Become, by W.C. Handy-Tim Brymn, Stomp Off Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Lemurs are one of many animals that help plants disperse their seeds throughout their habitat. (Photo: Darren Pearce, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There's an interesting study recently published in the journal Science, about plants that are dependent on birds or other animals to help spread their seeds to keep them alive. And if those birds or other animals are threatened and declining in population, and there's less opportunity to spread their seeds, the plants are then endangered as well.

BASCOMB: You know, it reminds me I did a story years ago in Madagascar, it was about lemurs. You know, when lemurs eat fruit, if the seed passes through a lemur first, it's got something like a 90% germination rate. But if the seeds don't first go through lemur, only about one in a thousand will actually germinate. So the forest, you know, really needs the lemurs to reproduce. And of course, the forest has a habitat for the lemur. So there's this really, really strong relationship there.

DYKSTRA: Always remember your Lemur Fertility Tip of the Day.

BASCOMB: You heard it here first, Peter!

DYKSTRA: Well, there's a big drop off with some species. If you're an animal, you can fly or walk or swim or slither to other areas, and that helps plants to prosper. If in the case of lemurs or other animals, those animals are declining, then plants don't have the benefit of spreading their local range. And it can be a real alarm bell for the health of certain plant species.

BASCOMB: Exactly. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: The National Butterfly Center is a private group, a nonprofit down along the Rio Grande near the town of Mission, Texas on the border. They've been forced to close because of QAnon conspiracy theories that say that this Butterfly Center, there for science and nature, is actually a nest of activities, not just for illegal immigration, but for drugs and weapons. And just like the story from the 2016 election, the conspiracy theories say that they're engaged in child sex trafficking.

The National Butterfly Center in Mission, Texas has closed to the public following threats from Q-Anon conspiracy theorists. (Photo: Runarut, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And of course, all of these are just blatant lies. There's nothing of this sort happening in this butterfly reserve.

DYKSTRA: Probably half lies and half hallucinations. All of it is crazy. This came about because of a lawsuit filed by the Butterfly Center. They're two miles from the Rio Grande, but part of the proposed border fence would go straight through their 100 acre property. They went to court to try and stop the construction of the fence. And immediately they were targeted by a wacky political theory.

BASCOMB: Why did it have to close though? I mean, were there threats against their lives, that sort of thing that that really forced them to close at this point?

DYKSTRA: Well, number one, they're closed to the public. Number two, the staff and volunteers are understandably, a little freaked out. They've received threats, including death threats. And if you're in the simple and noble business, of studying nature and educating about nature, that's one of many areas where this kind of lunacy has no place.

BASCOMB: No, certainly not. Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: Oh, this is one of my favorites, February 10, 1935, published in the New York Times, all the news that's fit to print, there was a story from Upper Manhattan, about an alligator found in the sewers. Some kids were shoveling snow into a storm sewer, they allegedly spotted a seven-foot alligator in the sewer in the middle of a New York winter. Obviously, there are no alligators in anybody's sewers in the north, but it's become an urban legend. Possibly, that's where the name urban legend or urban myth came from.

The sewer alligator urban legend has been memorialized by a permanent art installation from sculptor Tom Otterness at the 14th Street/8th Avenue station in New York City. (Photo: Martin Sutherland, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that does sort of seem like the mother of all urban legends. I mean, everybody's heard this story, right? I guess the idea is that somebody brought back an alligator from a vacation, it got too big, got out of hand, so they flushed it down the toilet, ends up in the sewer, and then the story tells itself from there.

DYKSTRA: That's right, the ultimate urban myth. Probably never happened. It certainly didn't produce a seven foot alligator surviving in New York winter. The rest of the story, according to The New York Times, is that the alligator was not seen again, after it was captured, brought up and then incinerated in a municipal incinerator.

BASCOMB: What? Okay. I never heard that part of the story. And frankly, I didn't know that it had been published in the New York Times. That adds credibility to this, this kind of outlandish tale.

DYKSTRA: All of the urban myths that are fit to print.

BASCOMB: Alright, well, Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website that's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Revelator | “Plants Face Tough Climate Challenges as Seed-Dispersing Animals Decline”

- The Washington Post | “The National Butterfly Center Closed Indefinitely. A Fringe Va. Candidate Is Partly to Blame.”

- Find out more about the origin of the “Sewer Gator” urban legend

[MUSIC: The Django Reinhardt Festival Live at Birdland, “New York in November” on Gypsy Swing! By Django Reinhardt, Kind of Blue Records]

Beavers Move Into the Arctic

Beavers are moving north at an impressive rate, changing the Arctic landscape with their expansive impoundments. (Photo: Mark Guiliucci, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Arctic is warming roughly twice as fast as the much of the globe, and some species are already moving toward the poles in search of new habitat. Moose, salmon, wolves, and grizzly bears are among the charismatic species on the move in the North, as well as a large, big-toothed rodent. As nature’s “ecosystem engineers” beavers are bringing big changes to the Arctic landscape. Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist and author of the book Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. He joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So what are the facts here? What do we know are the extents to which Beavers are moving North? And why?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, so beavers are colonizing or perhaps recolonizing the Arctic at a pretty impressive rate. The guy who studied this the closest is an ecologist named Ken Tape in Alaska. And basically what he found by looking at satellite images--because beaver complexes are actually so large and impressive you can see them in satellite imagery--is that between 1999 and 2014, beavers built 56 new complexes of ponds in this area in the Arctic that Tape studied. And beavers were actually moving north by about eight kilometers, so five miles or so, per year. So they're moving north at a really impressive rate. The why is basically because the climate is changing, and the habitat is becoming suitable for them, right? Beavers need trees. And as the willow line advances north into the previously treeless tundra, it's creating this available food and building material for them, this resource that beavers need. A big question is whether this is really a new colonization, or whether they're really recolonizing areas where they used to live, before they were trapped out by fur traders. So certainly they're moving north. Whether that's a novel colonization event or a recolonization is still to be determined.

DOERING: Right, because I remember when we talked about your book, Eager, you said that there were hundreds of millions of beavers all over North America. And they're now recovering, right? What do we know right now about how many beavers there are at this point?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, we don't have a great beaver population estimate for North America, you know, states or provinces really keep good track. But the best guess we have is something like 10 to 15 million beavers on this continent, which, you know, sounds like a lot, right? They're not an endangered species, certainly. But as you pointed out, you know, that's a tiny fraction of the beavers that used to live on this continent historically, you know, we know that pre-European arrival, there were as many as 400 million beavers on this continent. So this was once a truly prolific, ubiquitous animal.

Beaver complexes can bring surprising benefits to any landscape, such as fostering habitats for a variety of other species. (Photo: JLS Photography-Alaska, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So beavers are, of course, nature's engineers or ecosystem engineers. So on a physical level, how are beaver dams and ponds changing the Arctic tundra?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, I mean, certainly, as beavers build dams, you know, they create these giant impoundments, right, these, you know, these really impressive ponds, which can be many, many times the size of your typical Olympic swimming pool. And they're turning these historically kind of single-threaded channels and making them these big complexes of ponds and wetlands. And you know, the big concern that some people have about that is that as a result, beavers may be melting the permafrost. There is lots of methane locked up in that permafrost. So as beavers spread water out, they may be releasing a very potent greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. But of course, you know, beavers' contribution to climate change will always be a minuscule fraction of humans' contribution. So they're certainly not the ones to blame for this problem. And in fact, you know, I'd also point out that, you know, beavers are also fantastic sequesters of carbon, right, that you know, that a beaver colony, a beaver pond is full of all kinds of organic, carbon rich material. And there have been fantastic studies showing that beavers are locking up lots of carbon. So you know, while it's true that in the Arctic, they may be releasing methane, elsewhere in their range, you know, they're keeping a lot of carbon out of the atmosphere.

DOERING: Ben, I know that one of the reasons that beavers are such an attractive animal to bring back in certain places, especially in the very arid American West is because their ponds lock up large amounts of water on the landscape and help revegetate and add moisture to a landscape that's drying out because of climate change. What are the potential benefits that they could bring to the Arctic?

The frozen ground called permafrost is thawing as the Arctic warms, and scientists think beaver ponds may speed up that process, releasing the greenhouse gas methane. However, beaver ponds also help store carbon in landscapes, especially in lower latitudes. (Photo: Boris Radosavljevic, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

GOLDFARB: Yeah, you know, I've been interested in the way that some of these studies have been covered by the media, that the kind of the default assumption is that because beavers are moving to the Arctic, you know, yes, they're melting some permafrost, that must be a negative interaction. I remember a few years ago, the New York Times did a study where they called beavers "agents of Arctic destruction," as though beavers have done more to the Arctic than you know, than we humans have. And, you know, and to me, I mean, I think it's really important to remember that beavers are just these amazing keystone species, right? They're these animals that disproportionately support a lot of life wherever they are. I mean, because they create these wonderful pond and wetland complexes, you know, they just engineer fabulous habitat for all kinds of creatures, you know, trout and salmon, amphibians, waterfowl, songbirds, you know, other aquatic mammals like otters and mink and muskrat and moose. You know, you name it, you know, there's just this amazing body of literature about how important beavers are for other organisms, you know, so I think that it's really important to just keep in mind that you know, some of the changes that beavers are inducing in the Arctic may be beneficial for some species, you know that okay, perhaps the melting of the permafrost is negative, but you know, beavers are also to engineering habitat for animals that we know are moving north anyway, right? They're sort of paving the way for some of these creatures. So instead of "agents of Arctic destruction," you know, they're "agents of Arctic adaptation," at least for some organisms, I think.

DOERING: That's right, I mean, beavers are certainly not the only species shifting towards the poles as climate change happens. So how should we be thinking about which species, quote unquote, "belong" where in this new and evolving reality?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it's a really interesting, philosophical question, I think, I mean, are animals that move north because of our actions in warming the climate, you know, are those invasive species? I would argue not. They're animals that are just, you know, sort of resourcefully adapting to the conditions that we've created for them. You know, we know that salmon, for example, you know, salmon are basically disappearing, in a lot of California, their native range there, but they're also salmon showing up in in new rivers in the Arctic, where they haven't been seen before, you know, and we know that beavers create fantastic salmon habitat, you know, that baby salmon love to rear, to grow up, in the slow water refuges that beavers create. So I think that, you know, as I mentioned earlier, you know, I think that for salmon and some other species, beavers could be doing potentially, at some point, a lot of good.

Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist, editor, and Beaver Believer. (Photo: Terray Sylvester)

DOERING: You know, beavers, as we know, they can cause some problems for communities when they first move in, maybe recolonize an area. They do cut down trees, and they do flood areas. Can you give us an example of how communities in the American West, for example, ranchers, were able to gradually switch to a "pro-beaver" mindset and sort of see some of the benefits of these engineers?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it's a really good question. I mean, certainly beavers are not the easiest animals to live with. Right? There are all kinds of impacts to human infrastructure that beavers cause. As a result, there's this very long history of beaver persecution, right? First, we killed them for their pelts. And then as they started to recover in the 20th century, we killed them for having the temerity to mess with our stuff. And there are lots and lots of ranchers out there who I've talked to who told me, "Yeah, you know, yeah, my dad killed beavers, and his dad killed beavers, and his dad killed beavers for damming and irrigation ditches or you know, or road culverts or what have you. But, as the climate gets hotter and drier, and it becomes more and more important to keep water on the landscape, I think lots of farmers and ranchers are recognizing the benefits of having these animals around. Beavers are basically agents of water storage and water creation in a sense, you know, they create these wonderful watering holes and they're also irrigators, right? They spread water out, they force water into the ground. So they're, you know, when you look at a beaver pond, you know, you see all of that visible surface water, but you don't necessarily see the water table rising, the aquifers being recharged, the soil being hydrated. So there's lots of literature about beavers basically being irrigators, being plant producers, and if you're a rancher, you know with your cows in a valley with beavers in it, you know, you're going to have more forage for your cattle, you know, the beavers are just making the land lusher. So certainly, a lot of ranchers have appreciated that benefit.

CURWOOD: That’s Ben Goldfarb, environmental journalist and author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Living on Earth | “Eager: The Surprising Secret Life of Beavers”

- Living on Earth | “How Beavers Help Save Water”

- Ben Goldfarb’s website

- NOAA | “Beaver Engineering: Tracking A New Disturbance In The Arctic”

- The Guardian | “Dam It: Beavers Head North to The Arctic as Tundra Continues to Heat Up”

- NPR | “Beavers Have Been Moving Into The Arctic, Accelerating The Effects Of Climate Change”

[MUSIC: Paula Fuga, “Nose Flute Dub” on Lilikoi, by Paula Fuga, Pakipalka Productions]

Sounds of Winter

A beautiful winter landscape. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

BASCOMB: Winters can be cold and gray. But winter can also have a silver lining for those who take the time to listen. So from the wintery reaches of New Hampshire Living on Earth commentator Sy Montgomery explains.

[CHICKADEE CHIRPING AND WINGS FLAPPING]

MONTGOMERY: At no other time of the year are sounds so sharp. The scolding winter call of the chickadee. Wind howling through oaks, or whispering through pines. The clarion call of wind chimes, piercing as the cold itself.

[XYLOPHONE-LIKE SCALE OF WIND CHIMES SOUNDING]

MONTGOMERY: Hearing may be the richest sense. Helen Keller wrote she felt its absence a handicap far worse than blindness. As if to make up for winter’s void – of colors muted, touch numbed, and scents sealed – winter’s sounds are the most vibrant.

[WHIZZ OF RUBBER SNOW TUBE SLOWING TO A STOP, CHILDREN LAUGHING]

MONTGOMERY: Sound travels further over frozen ground. Frozen surfaces are rockhard, so they don't absorb sound – they reflect it. And when the atmosphere above is warmer than the ground, sound bounces back toward the ground. Winter’s freeze is like having a sound reflector in the sky.

[SCRAPING, RHYTHMIC GLIDE OF SKATES ON ICE]

MONTGOMERY: Winter’s bareness amplifies and clarifies its voices. Spring and summer are crowded with ambient noise: the sounds of birds and insects, the rustle of animals in the woods, the whisper of grasses and leaves – not to mention the hubbub of so many people and their machines.

[CREAK OF SWAYING TREE]

MONTGOMERY: In summer, leaves absorb sound, especially the higher frequencies. But now, the trees are bare, summertime’s murmurs are hushed, and snow is covered with hard ice crust. Sound slices through the air—stark, clear, pure.

The frozen land of ice and snow has a sound all its own. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

[CRUNCH OF FOOTSTEPS IN SNOW]

MONTGOMERY: So this is the best time of year, I think, to go somewhere secluded – just to listen. Listen for the voice of the wind. The ancients said that Boreas, the north wind, loved a nymph who was changed into a pine tree. Boreas still rages and howls through oaks and maples and beech, but his voice is quite different when he speaks to his love.

Listen to the voices of the trees. They creak like rusty hinges as they sway in the wind. Sometimes trees will even pop loudly – it can sound like fireworks – their wood expanding and contracting during sudden changes in temperature.

Listen to the voice of the ice. On a lake, sometimes, you can hear the ice squeak, or crack, or even boom. Even safe, solid ice will make a cracking sound as it expands. Scary to an ice skater – but if you’re walking in the woods, the booming of a lake is like music.

And remember, in winter, that one of the greatest rewards of listening can be silence. Orchestras know this. At the end of a performance of Mozart’s Fantasy in C Minor, a thousand ears strain for the last note.

[MOZART FANTASIE IN C MINOR]

MONTGOMERY: Silences are different in winter, too. This is not the soft, glowing stillness of pre-spring, or the absorbing quiet of swimming underwater. No, winter’s silence, like its sounds, is piercing, clear and cleansing, like a shooting star, well worth seeking and savoring.

[MOZART FANTASIE IN C MINOR]

BASCOMB: Sy Montgomery is the author of more than a dozen books including The Good, Good Pig, and The Soul of an Octopus. Her latest book called The Hawk’s Way will be out in May.

Related link:

Sy Montgomery's website

[MOZART FANTASIE IN C MINOR]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth