May 6, 2022

Air Date: May 6, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Whistleblowers Say EPA Endangers Public Health

View the page for this story

Five whistleblowers have exposed toxic working conditions within the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) New Chemicals Division. In their disclosure, they describe how scientists are forced to erase findings about cancer risk and other types of toxicity from safety reports and point to a huge revolving door between the EPA and the chemical industry. They also say the EPA is only slowly assessing some 80,000 legacy chemicals within daily household products like paint and pesticides that potentially contain hazards to human health and the environment. This week, host Steve Curwood is joined by Kyla Bennett, the director of science policy at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, is a lawyer who works with the whistleblowers. (14:38)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week's trip beyond the headlines, Host Steve Curwood talks with Environmental Health News' Weekend Editor Peter Dykstra about a study that shows how the fibers in discarded face masks could potentially strengthen cement. They then chatted about a new honeybee, bred by the United States Department of Agriculture, that could potentially be resistant to varroa mites, a parasitic mite which causes disease and death in European honeybees, which are widely used in commercial agriculture as pollinators. And then from the history books, the two recount when an American right wing political commentator falsely accused eco-terrorists of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill after the British Petroleum Company had already apologized. (05:31)

No-Mow May

View the page for this story

Biologists are encouraging homeowners to leave their lawnmower in the garage for a month this spring to create crucial habitat for pollinators. A proponent of the "No-Mow May" movement, Biology Professor Israel Del Toro from Lawrence University joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss why we should be rethinking our lawn care habits. (10:29)

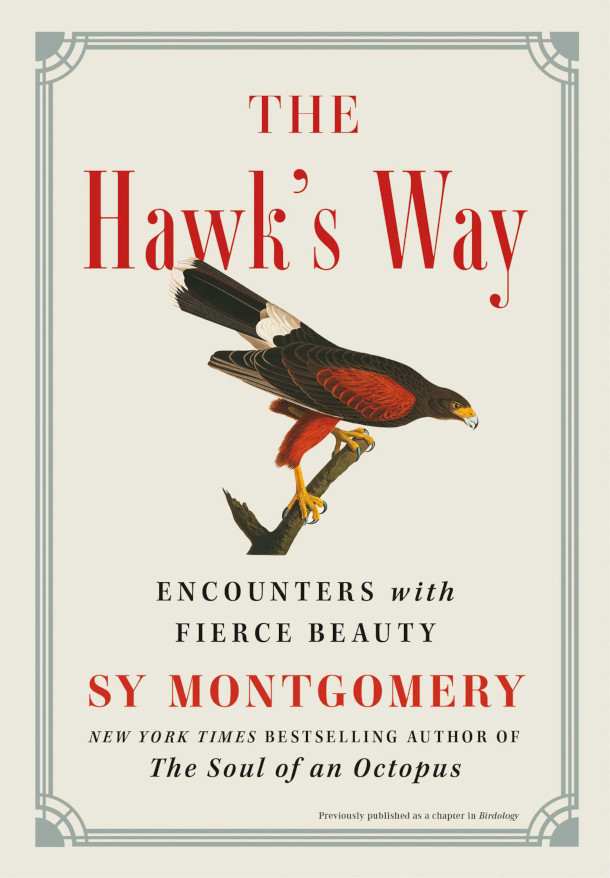

The Hawk’s Way

View the page for this story

Falconry, also known as the practice of hunting with birds, can be traced back perhaps as far as the Ice Age. Many modern aficionados, like author Sy Montgomery, consider the sport to be more about the interaction with these hawks, falcons, and owls, rather than about the hunting itself. Sy’s newest book is The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty, where she talks about learning the art of falconry. Sy joined Host Steve Curwood for the latest Living on Earth Book Club Event to discuss the wondrous world of these birds of prey. (17:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220506 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kyla Bennett, Sy Montgomery, Israel Del Toro

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Whistleblowers at the EPA say they’ve been forced to delete cancer warnings about new chemicals despite the risks.

BENNETT: The scientists who are responsible for figuring out whether new chemicals pose risk to human health or the environment they are being instructed to delete hazards from these risk assessments to make chemicals appear safer than they are.

CURWOOD: Also, the no mow May movement to let lawns grow and support pollinators.

DEL TORO: By reducing our mowing intensity we can actually increase pollinator abundance five fold and increase pollinator diversity or the number of species three fold (:09) Last year in Appleton we documented for the first time a rusty patch bumble bee right down town in the middle of a central park.

CURWOOD: And the Hawk’s Way with author Sy Montgomery. That’s this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Whistleblowers Say EPA Endangers Public Health

The EPA, according to Bennett, has done virtually nothing to regulate PFAS (forever chemicals) and since 2017 has not rejected any of the applications for the hundreds of new, potentially harmful chemicals being produced every year. She and other members at PEER joke that the EPA should stand for “Everything’s Polluted Anyways.” (Photo: Paul A. Fagan, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Five whistleblowers say the New Chemicals division of the Environmental Protection Agency bends over backwards for industry and has even deleted cancer risk findings for chemicals it has approved for public use. They claim this culture of deference to industry has allowed thousands of new and possibly dangerous chemicals on to the market and assert since 2017 the EPA has not rejected a single new chemical application. Whistleblowers say a revolving door between industry and the EPA creates a toxic work environment for career scientists who fear they may be forced to approve unsafe chemicals. For more, I’m joined now by Kyla Bennett, who represents the EPA whistleblowers. She’s a lawyer at Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, Welcome to Living on Earth!

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: What's going on right now, in terms of being a little too cozy with industry in the EPA's new chemicals division?

BENNETT: The scientists who are responsible for figuring out whether new chemicals pose risk to human health or the environment, they are being instructed to delete hazards from these risk assessments to make chemicals appear safer than they are, you know, where it says this is a carcinogen. It's crossed out, redlined out. Some of our clients have said, I refuse to have my name on that so-called science. And so management says, "okay, we'll have somebody else post it." In my mind, it's malfeasance.

CURWOOD: So how much danger health-wise does the American public face?

BENNETT: An incredible amount of danger. I mean, if you look at EPA's own data since 2016, they have prevented zero chemicals from going on the market. In other words, everything that comes before them, either gets approved, or not very often, withdrawn by the submitter. All of these chemicals going out, and we're talking about hundreds a year, are not being assessed properly. There's something like 80,000 chemicals out there are currently in commerce. The vast majority of those have never had risk assessments done. Because the statute TSCA that requires this risk assessment to be done came into being in 1976 that automatically grandfathered in all the chemicals that were already on the market. 10 chemicals a year they reassess these old chemicals to see if they're dangerous or not.

CURWOOD: That will take I guess, what 100 years,150 years to go through?

BENNETT: 7000 years.

CURWOOD: Oh, sorry. 7000 years it will take.

BENNETT: So the majority of chemicals that are out on the shelves of Target and Walmart and Home Depot and Lowe's, we have no idea what most of those do to us.

CURWOOD: How long have these transgressions been going on within the EPA?

BENNETT: A lot of people want to blame it on the Trump administration, and indeed it did get worse under the Trump administration. He brought in industry people to run the agency. Under the Biden administration, it's still occurring. We have audio recordings of some of these managers. They said, we just want a button we can press to override all the science. They have a category of cases called hair on fire cases. So anytime an industry or a congressional calls EPA and says, Why is it taking so long, it becomes a hair on fire case, and management takes it and gets it out faster. This is not the way this is supposed to work.

CURWOOD: How much pushback and work pressure are the whistleblowers at the EPA currently under? I mean, how much do they stand to lose?

BENNETT: One thing people don't understand is that these clients of ours become whistleblowers as a last ditch effort. So our five clients at EPA, they did try to use the administrative processes, for example, the scientific integrity policy, they tried going to their managers, they tried filing complaints, internally, nothing happened. So they felt like they were caught between a rock and a hard place. And they stand to lose their careers, their credibility, they’re pariahs to a certain extent. They're all facing incredible retaliation. And sometimes I jokingly say to my boss, I feel like I'm 1/3 scientist, 1/3 lawyer and 1/3 therapist. And they've come forward not for personal gain. But because they are so concerned about what these chemicals are doing to people's health and the environment.

CURWOOD: The journalism organization, The Intercept has been writing a series of articles about the whistleblowers, and one characteristic of their reporting is what looks like a revolving door between industry and the people who decide whether or not it is safe for the public to be exposed to chemicals. To what extent do you see a revolving door?

Chemists at the EPA have been forced to erase findings on the toxicity of certain chemicals. This is a stock photo of a laboratory, not an EPA lab. (Photo: PEO ACWA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BENNETT: I first have to say that The Intercept has done an amazing job. We didn't know who we could bring the story to, because it's very, very difficult and dense science. And I think Sharon Lerner has done an amazing job. And what you say is correct. There's one fellow who has been back and forth between EPA and industry, I think four times now. Of the past nine directors of the Office of Pesticides, seven of them currently work in industry, and the other two just retired. It's kind of a unspoken thing where you work for EPA, and then you'll get a job at industry so you can show them how to get through all those loopholes and get what you want. It's despicable.

CURWOOD: Now, the articles in The Intercept mentioned that the whistleblower report has been leaked to the staff members named in such a whistleblower report. How much does that compromise investigation? How unusual is that?

BENNETT: What happened is in order for the whistleblowers to get protection under the Whistleblower Protection Act, somebody in their management chain has to know that they are the whistleblowers. Because otherwise they could get retaliated against. And the managers could say, oh, I had no idea it was you who was the whistleblower. So in this instance, we sent the disclosure to Dr. Michal Freedhoff, who's the Assistant Administrator, the political appointee for the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention. And within three minutes, she sent it to one of the people named in it, and that person then said, please send it to everybody who's named in this complaint, and they actually held a meeting, presumably to figure out how they were going to protect themselves. Does that compromise the IG's investigation? Yes, I think so. It was very disturbing and very unusual to have this happen.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent are the transgressions you're talking about at the EPA attributable to burnout, understaffing versus just pure negligence or maybe even some more pernicious motives?

BENNETT: It is absolutely true that EPA is under resourced. Dr. Freedhoff has been begging Congress for more money. She claims that this particular division needs at least twice as much money. I agree with her. They're not getting it, by the way from Congress. So that's definitely part of it. But it goes deeper than that. You know, most people when they think about doing risk assessments on chemicals, they probably visualize these people in these white lab coats and labs with, you know, test tubes and Erlenmeyer flasks. That's not what happens. They get the name of the chemical, and they get sometimes just an abstract of an industry sponsored study. And from that they have 90 days to figure out whether this chemical presents a risk or not. Now under the statute, TSCA, they are allowed to ask the submitters for more information, but EPA doesn't let them do that. So yes, resources and funding is definitely a part of it. But honestly, they are allowed to say no, and they are not saying no. And that's the bigger problem.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, the studies on these chemicals—those are studies conducted by the industry itself?

BENNETT: Absolutely. And that's a problem right there. Because as we all know, industry studies can be biased. They are providing their own scientists' studies saying we think this is safe, you've got 90 days EPA to tell us whether you agree or not. I mean, it's really scary. And what they often have to do is rely on an analog—it's a structurally similar chemical. And then they can say, well, this other very similar chemical causes cancer or is a mutagen. And therefore, we think that this new chemical might act the same way. But one of the more frightening things for me is part of tsca section 8(e) requires submitters of chemicals, if they come across information that leads them to believe that their chemical could be a substantial risk to human health or the environment. They have 30 days to send EPA that information. And EPA is supposed to post them on this public facing website called Chem view. And they haven't posted any since 2017. They've been coming in getting stacked up, and they claim they didn't have the resources to post them. In other countries, chemicals are guilty until proven innocent, and in the United States of America gosh, darn it, they're innocent until proven guilty. And they make it as hard as possible to prove them guilty.

CURWOOD: What's the workplace climate like at the EPA, in this division, where the folks are reviewing new chemicals?

BENNETT: I have never seen a division so demoralized, intimidated, unhappy and scared. One of the things EPA did do when we started bringing these issues to the public is they did a survey and the people in the division were saying that the division is toxic, that industry is running it. They're all afraid that they are gonna be responsible for the next PFAS that's killing people. They're all miserable. It's absolutely heartbreaking.

CURWOOD: How are managers or workers' performances measured within the EPA? I mean, what are the metrics and standards that they are held to?

BENNETT: EPA's bean counting seems to be based on how many chemicals do you get out on the market within that 90 day statutory timeframe? What I think it should be is how many chemicals that are dangerous did you prevent from getting out on market? I mean, we joke around that EPA should stand for everything's polluted anyway, instead of the Environmental Protection Agency.

CURWOOD: By the way, how does the EPA’s handling of these chemicals compare to some other international agencies?

Glyphosates and neonicotinoids are known carcinogens, yet are still approved for use by the EPA. (Photo: Scot Nelson, Flickr, Public Domain)

BENNETT: EPA, I think is one of the worst. Look at PFS as an example per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances. We have a national contamination crisis. Every one we look at as toxic, they call them forever chemicals because they don't go away. Even here in my little town in Massachusetts, I cannot drink my water because of how much PFAS we have. What has EPA done? Nothing. They have not banned any of them. They have a guideline on two of them. Europe is moving ahead with banning them as a class.

CURWOOD: What's your wild guess as to how many adverse health effects are in our population from the EPA's failure to appropriately regulate these chemicals?

BENNETT: Virtually every environmentally induced health effect that everybody has is from something that came across EPA's desk, everything, everything. Except for maybe skin cancer, they say something like 15% of cancers are from viruses, but the other 85%, they're from chemicals.

CURWOOD: So what kind of short term measures can people take? How can we know to protect ourselves?

BENNETT: The only thing that I tell people is to try to go as natural as possible. When my husband and I walk our dogs around the block, I can smell people's fabric softeners come out of the dryer vents. Those are carcinogens. These safety data sheets, which are supposed to inform workers or consumers don't have the information on them because of what EPA is doing. So basically, the short answer to your question is it's impossible to know.

CURWOOD: So how can communities act to pressure the Environmental Protection Agency?There’s a special class of communities are at risk. Those folks who live on the fence line of manufacturing facilities or low income minority communities that are already disproportionately exposed to toxins and emissions and don't have the health care options that many people do have? What can be done?

Whistleblowers expose corruption in EPA chemical safety office. https://t.co/mfCq1tdPuv

— The Intercept (@theintercept) July 4, 2021

BENNETT: You know, we're here to help. There are other environmental groups that are trying really hard to help. Environmental Working Group and Earth Justice. But if you look at, for example, Cape Fear in North Carolina, those community groups are fighting back really, really hard against the PFAS contamination in their towns. Flint, Michigan, they've got some great activists there, their water is still not safe to drink. And not only do they have lead, but they have PFAS as well. The only advice I can give them is to do Freedom of Information Act requests to EPA, push them, call your Congressionals, both state and federal. So many people think that because a Democrat is in office as President, that the EPA is okay. It is absolutely not the case.

CURWOOD: So what about the investigation into the EPA, what kind of changes are possible?

BENNETT: I have a lot of hope with the Inspector General. They are taking this very seriously. They have a team of people, they got confidential business information, CBI, cleared. They brought on board chemists and toxicologists to review the information that we've given them, but it's slow going, and we gave them so much information. I'm hoping that the investigations are finished sometime this calendar year. But the tricky part is that once the inspector general comes out with a report or reports, they don't have enforcement power, its recommendations to EPA. So what do we think EPA is gonna say? While we may be vindicated, is the problem going to get fixed? I honestly don't know.

CURWOOD: Kyler Bennett is Director of Science Policy for Public Employees For Environmental Responsibility. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

BENNETT: Thank you so much for having me. I really enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Kyla Bennett’s website at PEER

- The Intercept’s series on the EPA Whistleblowers

[MUSIC: Airto Moreira, “Hala, Tumba and Timbrel” on Life After That, by Airto Moreira/Giovanni Hilalgo/Mela Noite, Narada World]

CURWOOD: Coming up –-a campaign to leave lawn mowers idle for the month of May. No Mow May is ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gerry Beaudoin and the Boston Jazz Ensemble, “Willow Weep for Me” on In a Sentimental Mood, by Ann Ronelle, North Star Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Researchers at Washington State university found that repurposing facemasks and using them in cement could make concrete 47% stronger which can potentially reduce the over 1500 million facemasks discarded every year. (Photo: Babette Plana, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

And for our walk behind the headlines today, we're gonna be talking as usual with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org. And dailyclimate.org. He's down there in Atlanta, Georgia. Peter, what do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve, we're gonna start with something that's potentially good news. The COVID pandemic has left us with a situation where we're up to millions of disposable face masks per minute. Being thrown out after one use estimated 1500 billion face masks around the world in a single year. But we may have found something that makes those face masks have a second life and something that actually in a small way could address climate change.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter, I'm wide open for this possibility. What do you got?

DYKSTRA: Well, the single use medical masks are usually made of polypropylene or polyester fabric, tiny fibers that may have a second life in the concrete industry. Concrete use has gone wild in recent years. As the developing nations ramp up their economies, concrete buildings are going up everywhere. But those microfibers in masks can be added to cement. And a Washington State University research project says that they can help make concrete stronger while dealing with a big disposable.

CURWOOD: Concrete certainly has an influence on the climate, I think what 8,10% of emissions are from cement kilns. So how much stronger would these mass materials make concrete?

DYKSTRA: There's one estimate that says possibly nearly 50% stronger. Those masked materials can help the builders in addition to helping the disposers throw away less.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and a great thing about this possibility is, is that concrete breaks down. You know, you may notice the odd bridge that collapses and such like that, that stuff wears out. If these fibers from all these masks can make these things stronger it's all to the good. I hope this works out, Peter. Hey, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Another potentially good thing for the environment. We've reported for years that honeybees are under serious threat, there's a real possibility that they could vanish someday. There are so many honeybee colonies lost from summer to winter to summer again, as much as nearly 30%. That's because of a number of threats, these pesticides changes in local habitat, loss of honeybee nutrition. But one of the biggest threats it's believed are a tiny invader called varroa mites brought over here from Southeast Asia in 1987. Scientists at the USDA, the Department of Agriculture, believe they've bred a new bee that's resistant to varroa mites.

Varroa mites latched on to the back of a honeybee, bees which are widely used in commercial agriculture as pollinators. The Varroa Mite is an external parasitic mite which attaches to the body of the bee in order to feed on hemolymph. In the process the mite spreads viruses that can lead to death and a significant infestation can lead to the death of a bee colony. (Photo: Absolute Folly, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND, 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Peter, what's the buzz on these bees?

DYKSTRA: The buzz on these bees is that it's potential. That with this new honey bee breed, replacing the European honey bees that have absolutely no natural defense to varroa mites, that we could save bee colonies without losing the honey they produce, or the pollinating feature that's so important that they perform for other food crops throughout the world.

CURWOOD: Yeah, boy without the bees, there's a lot of food we wouldn't have so I like the sound of this.

DYKSTRA: If it all works, it's a win win.

CURWOOD: Okay, let's take a look now back in history, Peter. Tell me, what do you hear?

DYKSTRA: April 29, 2010. One of the champions of fake news and conspiracy theories was of course the late Rush Limbaugh. Mr. Limbaugh died last year. But right after the Deepwater Horizon disaster he went on his nationally syndicated show and suggested that eco terrorists had deliberately caused the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

CURWOOD: Wait, Peter almost immediately BP itself said that they messed up by allowing this well to blow out. What gave Limbaugh the notion that somehow he could say that there were eco terrorists involved?

DYKSTRA: Well, you know when BP immediately apologized for its role in causing the spill, I began to grow a little bit suspicious that they had actually helped cause the spill. But not Rush Limbaugh. He stayed on it and actually doubled down a few days later, when he added that not only were eco terrorists using this as a lobbying chip for climate and energy legislation but in addition they had done it to promote Earth Day. You'll remember that the well blew on April 20th and the massive spill was detected two days later April 22, Earth Day. A true conspiracy waiting for someone like Rush Limbaugh to knock it out of the park.

On April 20, 2010, the oil drilling rig Deepwater Horizon, operating in the Gulf of Mexico, exploded and sank resulting in the death of 11 workers and the largest marine spill in history. In 2012, the oil company BP agreed to accept criminal responsibility for the disaster. (Photo: Casey Ware, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well Peter, we don't have Rush Limbaugh around telling outrageous lies but I think a lot of people have picked up his mantle and moved it forward sadly.

DYKSTRA: Well, I'll get back to you after the 2020 election is resolved.

CURWOOD: Thanks. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news, that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website that's LOE DOT ORG.

Related links:

- Cosmos | “Disposable COVID Masks Make Stronger Concrete”

- Read the study on repurposing face masks for concrete

- The Week | “The Conspiracy Theories Behind The BP Oil Spill”

- Science Tech Daily | “New Breed of Honey Bees a Major Advance in Global Fight Against Parasitic Varroa Mite”

[MUSIC: Speedo Harmonica Jones, “Making Out In the Street” on Indescribably Blue, by Chris Youlden, self-published]

No-Mow May

Leaders in the “No-Mow May” movement stress that there is a key window of time–anywhere from February to May depending on an area’s climate–when vital food sources for pollinators should be allowed to flourish. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The single largest irrigated crop in the continental United States is grass, as it occupies nearly 2 percent of the land. And this time of year in the cooler parts of the Northern Hemisphere that grass may be spotted with cold-hardy dandelions, and violets, or even rare types of clover. And these are some of the first bits of food for hungry insects just waking from the long cold winter. Insect populations, including many critical bee and other pollinator species, are in dramatic decline, threatening food webs in nature and food security for humans. So, instead of cutting the grass and early blooms just when insects need them the most, some biologists are encouraging homeowners to commit to a no mow May. A movement that began in England has now spread to dozens of US cities including Appleton, Wisconsin where city policy encourages people to wait until June to mow their lawns. Israel Del Toro is a biology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton who has advanced this movement. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: So many people probably think that spring is a good time to clean up their yards. But you're saying that we should resist that urge. Why?

DEL TORO: Yeah, the idea is pretty simple. May is actually a really important time for our pollinators that are just coming out of hibernation. So many of the species of bees that we have in the US are solitary bees that over-winter underground. And so the idea behind No-Mow May is to basically let our lawns grow out and provide some early season flowers for our pollinators that are coming out of hibernation to feed on.

BASCOMB: Well, this time of year in my own yard, I'm seeing dandelions and some violets coming out. But what kind of flowers are we talking about here? I'm sure of course, it's gonna to vary across the country, but generally, what are you seeing?

DEL TORO: Yeah, things that we would normally consider weedy species are actually really important food sources for our pollinators. So things like what you just mentioned: dandelions, clovers, violets, all of those are resources, whether native or not, that our native bees are actually depending on. Now, don't get me wrong, I'm all about removing invasives and reducing invasive species as well. But we also want to make sure that we strike a balance in working with the biodiversity in our backyards.

BASCOMB: Well, tell me more about the insects and pollinators specifically that we're talking about here.

There are about four to five thousand species of native bees in the United States alone, and many of them rely on naturally growing vegetation in urban spaces. (Photo: Allison Richards, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DEL TORO: Yep, so pollinator diversity is actually really huge. If we look at the entire US as a whole, we're looking at about four to five thousand different species of native bees. Most of them are solitary bees, and actually very few are colonial like honey bees, or semi-colonial like bumblebees. The rest of them tend to be solitary. They nest underground, they nest in decaying wood. Some of them lie in their burrows with leaves, those are your leaf cutter bees, or others will dig out little burrows inside of walls. And those might be your mason bees. And so we have quite a big diversity of bees. Here in Wisconsin, we have about 500 different species of bees that are native to Wisconsin. And amongst that biodiversity, we also have rare and endangered species. So a good example of that is the rusty patched bumblebee. The rusty patched bumblebee is federally listed as it's a critically endangered species due primarily to habitat loss. But one of the cool things that we're seeing is that these urban habitats that we're generating as a result of No-Mow May, can actually result in bringing back some of those populations into urban spaces. Last year in Appleton, we documented for the first time, rusty patched bumblebee right downtown in the middle of a central park.

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. Wow, that's amazing. I know that you've performed some preliminary studies that measure the impact of lawns on pollinators. What have you found?

DEL TORO: Yep, so we've collected two years of data right now on No-Mow May and its effect on pollinator diversity and abundance. And what we found in year one was that by reducing our mowing intensity, not mowing during the month of May, we can actually increase pollinator abundance fivefold and increase pollinator diversity or the number of species threefold. And so it doesn't mean that we're necessarily having more bees, but our bees are at least using these spaces that are No-Mow spaces. So we know we're feeding the bees at least. And in our second year, we decided to expand it out to a couple of communities to see if this was a pattern that was just exclusive to Appleton, and we're a little bit more generalizable. And what we found was pretty much along the same line into other communities, Oshkosh and Wausau, Wisconsin, both saw an increase in abundance in bees as well. But one really interesting thing that we saw last year was that not only are we increasing the diversity of bees, we're also increasing the diversity of all insects, which is really great to see because insects are really this foundational layer to an ecosystem. They provide food for other organisms, as well as ecosystem services like pollination, and weed and pest regulation. So those things are really important things that insects are doing for us in these urban habitats.

Bees are not the only species that can benefit from No-Mow May. A variety of rarer plants and insects are also free to thrive when our lawns are not as manicured. (Photo: Yamanaka Tamaki, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So even somebody that maybe doesn't care so much about bees or insects, but might like to hang that bird feeder outside their window and see birds, maybe they should think about taking up this No-Mow May. I mean, as you said, insects are so foundational to many species that we care about.

DEL TORO: Absolutely. So with insects being at the base of many of these food webs, birds and other small mammals rely on them as a part of their diet. So by increasing the abundance of insects in general, we can really start to help the broader ecosystem as well. One of the other cool things that we see as part of No-Mow May, so let's say animals and insects and birds aren't your thing, but maybe plants are your thing. No-Mow May also gives an opportunity for rare and endangered species of plants to pop up, things that might not normally show up.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's really interesting. So it sounds like May specifically is a really critical window for a lot of things.

DEL TORO: Yep, May is when nature is waking up from winter, right? Now depending on where you are in the US, No-Mow May may might not be the right time for you to not mow your lawn. It might be No-Mow April if you're further south, or No-Mow March, just depending on where you are, and wherever the seasonality is appropriate.

BASCOMB: Well, how big is the potential impact of yards, for pollinators and for wildlife in general? I mean, we grow a lot of grass in this country.

DEL TORO: That's right. So grass is probably our predominantly most homogeneous crop that we grow as a country and we manage it so heavily, right, we put all of these chemicals, fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and to have that greenest lawn. And maybe this is an opportunity for us to rethink some of those habits and educate ourselves on what the best practices are, and maybe reducing our fertilizer use or reducing harmful chemicals that are known carcinogens. For example, glyphosate and neonicotinoids are really bad for our pollinator populations. But they're also really bad for us humans. The European Union, for example, has declared glyphosates as known carcinogens, and we still keep putting them on our lawns, and often overusing these chemicals. So this is an opportunity for us to think about what's good for the environment, but also what's good for our own health and our practices on how we manage our little bits of plots of land.

BASCOMB: So we've been talking about holding back on mowing our lawns. What about cleaning up, you know, last year's leaves or pulling out those dead flower stalks? I understand a lot of insects make their winter homes in places like that.

DEL TORO: Absolutely. So No-Mow May isn't just an opportunity to be lazy. In fact, I encourage you to do the opposite. I encourage you to spend that time that you would normally spend mowing, educating yourself about other things that you can be doing for our pollinators throughout the summer and into the fall. And as you mentioned, going into the fall is a really important time where we can help create habitat, nesting habitat for these solitary bees. We like the idea of "leaving the leaves." The other great thing about leaving the leaves is that it becomes great compost for your yard and for your lawn in the next year. So not only are you protecting your pollinators, but you're fertilizing your landscape as well along the way.

While many may view plants like dandelions as a nuisance, they are actually important to a wide variety of pollinators. (Photo: Yoshiyuki IMAI, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Israel, I have to tell you that this has become a bit of an issue in my own house here. My husband mows the lawn. And he's already talking about how long the grass is getting, I kind of think he's worried that the neighbors are gonna judge us for not keeping our yard neat enough. How do you respond to someone with those kinds of concerns?

DEL TORO: Yeah, so the big thing is open communication and talking to your neighbors about what you're doing and why you're doing it. So if you decide to grow out your lawn for the month of May, the first thing we ask you to do is check with your local municipality to make sure that you're not violating some city ordinance. However, if your town is participating, or you are within your city ordinances, then you know, by all means, just talk to your neighbors. Let them know that yeah, my lawn’s gonna be a little shaggy this month. But that's okay. This is why I'm doing it. And I promise, come June, I'm gonna mow that thing. And we're all gonna be looking top shape. And you know, one of the things that we do is we provide signage for our communities to let people know that our wild looking lawns actually is a sense of organized chaos, that there is method to our madness, right, that we're not just being lazy gardeners, we're actually thinking about providing homes for our pollinators.

BASCOMB: Well, where have you seen some success with the No-Mow May movement? And what kind of pushback are you getting?

DEL TORO: It's really interesting, I was just at a common council meeting last night in the city of Manasha, which is a neighboring city to the city of Appleton. And what we saw is a lot of pushback from legislators there. So the legislators, they're saying, oh, you know, we're just not comfortable with this idea. We take a lot of pride in managing our lawn, or I just had a chemical company come and treat my lawn yesterday, so I'm not supporting this. And so there is a lot of pushback from local governments, because there's fear of the unknown. There's fear that things might get too crazy and out of control. But I think what we've shown here in Appleton is that those fears aren't founded in reality, like at the end of the month, Appleton yards go back to looking normal.

BASCOMB: So No-Mow May isn't a slippery slope to bedlam, then. It’s gonna be okay.

DEL TORO: No, I think No-Mow May is more of a slippery slope into learning about your biodiversity and educating yourself and your family, about the little things that crawl outside our house that are really important for our ecosystem.

CURWOOD: Israel Del Toro is a biology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Xerces Society | “No-Mow May Sign Download”

- Pollinator Friendly Alliance | “What is a pollinator lawn?”

[MUSIC: Alison Brown, Mamo Banjo Festival (Revisited) on Alison Brown Quartet, by Alison Brown, Vanguard Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A tale of falconry with animal whisperer and author Sy Montgomery and her new book, The Hawk’s Way. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Alison Brown, Mamo Banjo Festival (Revisited) on Alison Brown Quartet, by Alison Brown, Vanguard Records]

The Hawk’s Way

The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty is author Sy Montgomery’s latest book. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

Falconry or hunting with birds possibly goes back to the end of the Ice Age or even before, and it was common in ancient civilizations. Falconers traditionally worked with trained birds of prey to hunt game together and share the spoils. Today for people like author Sy Montgomery this sport is more about the joy of interacting with the birds themselves. Sy has written 29 books for children and adults, most about animals and the people who engage with them. Her latest is The Hawk’s Way: Encounters With Fierce Beauty. In it, Sy tells of learning the art of falconry from her mentor Nancy Cowan, from feeding these birds with parts of frozen baby chicks to understanding hawk psychology. Sy joined me for a live discussion as part of the Living on Earth book club at an event sponsored by New Hampshire Audubon and New Hampshire Public Radio. I asked her to describe how she felt the first time a hawk perched on her arm.

MONTGOMERY: It was like holding a waterfall or a lightning storm, or an eclipse on your glove. When Jazz, the first hawk to land on my falconry glove landed, I was shocked at how heavy she was. I was shocked at the squeeze of her strong yellow feet. I was completely filled up with the splendor and the wildness of his creature, like wildness itself had come out of the sky to me.

CURWOOD: I gotta confess, I wasn't sure about this book. Because Sy is famous as a vegetarian. And this book about the way hawks operate, it's about as far from vegetarian as you get! And in this book, you have the heads of these baby chicks are being chopped off, their legs are being chopped off, their hearts are being pulled out to become food for hawks in training. So, one of the recurring themes in this book is how your vegetarianism, you know, and your interest in falconry. I mean, like, you're at war with yourself.

Sy Montgomery (left) reads an excerpt from The Hawk’s Way to the audience. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yeah, that's right. I mean, the last person you would think, would practice falconry. If I found there was a steak on my plate, I would push it away. But when you're in the company of one of these magnificent birds, what you have is glory, what you feel is their hunger and their delight. What you feel is, there there's a word in falconry for their desire to hunt. And it's called yarak. And it's such an ancient word, no one really knows for sure where it came from. But a hawk lives to hunt, not just to eat, a hawk wants to chase and capture even more than it wants to eat. And that glorious desire, seeing that desire unfold and be fulfilled, that animal's joy can become mine. And to be able to understand or even come close to touching a mind, so different from my own.

CURWOOD: To somehow enter the heart and mind of a hawk?

MONTGOMERY: Well, this is what we want. This is what we always want with everyone, you know, with our friends, and with our family, and with the animals that you see, you want to know, What's it feel like to be you? I think it was kind of soul cleansing, for me, to let go of so much that was about me. It wasn't about me. It was about joining them and respecting that ancient drive and desire that hawks have, which really goes all the way back to the dinosaurs, because as you know, birds are dinosaurs. And all the dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, except for the ones who fly. And when you have one of these creatures on your arm, you're holding a dinosaur right there. They're not just descendants of the dinosaurs. They're descendants of a very small wing of the dinosaur clan, the theropod dinosaurs, the meat eating dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: From the little, from the velociraptor to the, dare I say, the Tyrannosaurus?

Sy Montgomery’s first experience with falconry was with Jazz, a four-year old female Harris’ Hawk like the one pictured. (Photo: John Rutter, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: That's right. Like T Rex. And you know T Rex when he hatched out of the egg. He was covered in down.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Let me ask a general question about birds in captivity. How do you feel about people keeping birds in captivity?

MONTGOMERY: It's hard to keep a bird in captivity and keep it happy. It's hard to keep a lot of animals in captivity and keep it happy. The thing about falconry hawks, though is if your hawk doesn't like you, it will fly away and you will not see it again. Because you don't just keep them on a string. Your hawk can disappear, and this happens. And I read, I think this was in one of Steve Bodio's excellent books, A Rage for Falcons, that he knows of wild hawks that would come out of the woods, never had any jesses on their feet, had never been in captivity and would join the hunter. Because the hunter makes a good junior hunting partner. So if that person will scare up game, the hawk figures out, bam, you know, this is someone I want to stick around with. And my falconry instructor Nancy Cowan was very clear that this is a voluntary association, that your hawk will just disappear if you don't measure up. And you can even be nice to the hawk and like the hawk, but if you're a lousy hunting partner, they're out of there.

CURWOOD: So, in this process of falconry, actually, you're working for the hawk. That you're the servant, you're the assistant, helping, but the hawk is in charge.

The Living on Earth Book Club hosted its first live, in-person event since early 2020 at the McLane Center of New Hampshire Audubon. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Totally in charge. And you cannot break their rules. All the rules are their rules. Nancy was very clear about this. And sometimes they will have rules that you don't understand at all. But they'll let you know when you broke them. Nancy had this one incident. Her husband, Jim Cowan, was a master Falconer, from whom she learned the art of falconry. And he had several hawks and she had her hawks, his and her Hawks. And one day it was their anniversary. She was all dressed up. Jim got home late. He wanted to take a shower before they went out to dinner. So he said Oh, would you feed my goshawk? Oh, sure. New goshawk, tell me what you usually do. He says you present the first chick, goshawk eats it. Present the second chick, goshawk eats it. Present the third chick, goshawk eats it, you turn around, you leave. Fine. So she does this. First chick goes fine. Second chick goes fine. Third chick is fine. She turns to leave. And then the goshawk fluid her face and stuck his talon almost through her eyeball. So it's a bad anniversary. So she was very annoyed when Jim finally emerged from the shower. And she wanted to know, what didn't you tell me? What did you forget to tell me. And the reason that goshawk had attacked her was that usually after the third chick, he would reach out, and fluffle, fluffle, fluffle on the birds chest. That was the routine. And she had not done the routine. And so the bird instantly felt like, oh, something's really wrong, I gotta go for the food and went for her face. And the amazing thing though, was that she was mad at Jim. She wasn't mad at the hawk. Because that's just what they do. So you've got to learn not to make a mistake. And if you make a mistake, you can pay. So you know, I was very, very careful with these birds. Another reason that you're careful is, more importantly than you don't want to get hurt, these birds, although they're tremendously strong, and some of them like the Peregrine can fly down like a lawn dart at 240 miles an hour, even though they have immense strength in their, in their feet, and their bills. And they have all these amazing superpowers. They're quite delicate, actually. And just if you have a hawk on your glove, just a funny little wind can lift a wing and hurt that hawk. If you're walking through the forest, trying to get some game and you fall. And that bird falls into you know, a twig that pokes in its eye, your bird can be blind, you can kill your bird with a mistake. So you got to be really careful that you do everything right.

CURWOOD: So how do you get these hawks? How do you get these predators, that you then become the junior partner of?

Falconry is the sport of hunting with birds of prey. (Photo: Tiarescott, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Well, I never had a hawk at our house. I kind of had to choose between the hawk and my marriage. So my husband Howard considered a hawk like having a loaded gun in the house. He really didn't want it. So, that wasn't happening. But to become an apprentice, an actual apprentice. What you have to do in New Hampshire is you capture a red tailed hawk, it needs to be a bird of the year, it can't be an older bird. It needs to be a young bird because you know, this way you may help the population instead of just deplete it. 80% of young hawks die in their first year. If you capture a red tailed hawk for falconry, many of the falconers will release that bird at the end of the year and just let it fly free. And what you've done is given it a head start in life, because normally 80% will not survive that first year. And to capture it, there's a whole system of stuff that you need to do. I mean, first, you go to a place where you've seen hawks, and you get an unfortunate rodent, who is going to need therapy after this. And you can put it under what's called a Bal-Chatri, which looks kind of like a basket, but the hawk can see through, it's got a lot of holes, and it has all these little Velcro like loops on top of it. And the poor rodent is there, the hawk can see this very easily. From 1000 feet, they can see prey within a couple of miles. And it will come down to try to capture the rodent and its talons will get stuck. Meanwhile, you're hiding in your car or in the bushes, and you rush out and you detangle that bird and then you take it home, that's how you get them. After you've got your falconry license. You can also actually order birds from breeders.

CURWOOD: So, what is the nature of this relationship? And I mean, what's in it for the hawk? And what's in it for the falconer? What seems to me that, you know, us people were kind of opinionated, we want to dominate but in a way we are not at all dominated.

MONTGOMERY: No, it's true. What is in it for the hawk is I might be able to scare up game just by crashing through the underbrush. And my big heavy feet will make some vole or squirrel rush out. And this is why hawks will even get over their aversion to dogs. Most hawks hate dogs and will scream at the dog. You horrible thing, I hate you, go away, you're a dog! But once the dog points the game, and once they make that connection, like ooh, the dog's pointing the game. Now they don't want to hate the dog anymore. That doesn't mean they have great affection for the dog, but it means that they will tolerate the dog. But as far as what is in this for the falconer. I wrote about that a little bit.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Steve Curwood (right) have worked together on a number of stories, including an interaction with Octavia the Octopus at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

CURWOOD: Just a little?

MONTGOMERY: Would you like me to read a piece of that?

CURWOOD: Sure.

MONTGOMERY: This is what I found was the greatest gift of falconry. Just like friendships with different people, relationships with individuals of other species have lessons to teach us. We are of course, deeply enriched simply by learning about life ways other than our own. I love it that some creatures I've been privileged to know can taste with their skin (octopuses), see with sound (dolphins and bats), and perceive colors that we can't even imagine (birds and reptiles). But animals also have much to show us about how we, as humans, can more meaningfully and compassionately encounter the wider world. Our fellow animals teach us lessons about the delights of sameness and difference. They immerse us in wonder. They lead us to humility. They inspire us to reverence. They teach us the many facets of love. The ancient Greeks said there were four kinds of love. The highest form of love was called agape. This is a love, untainted by expectations, a love without external reward. In the Bible, agape came to stand for the love God has for his creation. For the love humans should endeavor to feel toward the creator and worship. Agape asks nothing in return. This is what a hawk can teach you. How to love like a god.

CURWOOD: With a fair amount of reluctance I have to bring this to a close. This is such an amazing book. And you're such an amazing writer, but also such an amazing person. And you know, if you have small people in your life, by the way, there's a whole bunch of books that Sy has written, sometimes focusing on scientists who are doing stuff, written in language that's more accessible for younger people. And then of course, the prose that you've put together, whether it's The Good Good Pig or, of course, The Soul of an Octopus.

MONTGOMERY: Well, gosh, you know, you're in that book, Steve. One of the best scenes in Soul of an Octopus had Steve in it, because he came with his crew to meet, it was Octavia?

CURWOOD: Octavia, yes.

Sy Montgomery with her dog Thurber (right), as well as a friend’s dog (left). (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

MONTGOMERY: Yes. And Octavia pulled a fast one on us. All of us were there just lost in the excitement of touching her and feeding her and we had this bucket of fish and we were handing her fish and it was sliding down her arms to her mouth because her mouth was in her armpits. Of course, where else would it be? And so there was like six of us all around the tank and we're all like, not just watching the octopus. Our hands are in the tank and the octopus. And then we thought, oh, you know what, let's get another fish and we look in like, where's the bucket? Do the bucket? No, no, no, the bucket. She had stolen the bucket of fish right from under, literally under our noses. That's how smart they are.

CURWOOD: It's amazing. Such a hugely intelligent, sentient animal that looks nothing like the rest of us.

MONTGOMERY: No, we last shared a common ancestor half a billion years ago, when everybody was a tube.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery’s new book is The Hawk’s Way. Thanks Sy! Im looking forward to your next one.

MONTGOMERY: Great, thank you, Steve.

[APPLAUSE]

Related links:

- Find out more on “The Hawk’s Way” on the Simon and Schuster page

- Find the book "The Hawk’s Way" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full video of Steve and Sy's conversation

- Sy Montgomery's website

[MUSIC: Steve Miller Band, “Fly like an Eagle” Instrumental Cover Version Studio-Ron]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth