July 8, 2022

Air Date: July 8, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Getting Plastics Out of the Parks

View the page for this story

To help curb the plastic pollution crisis, the US Department of Interior will phase out single-use plastic products sold and distributed in national parks and other federal public lands it oversees. Christy Leavitt, Plastics Campaign Director at Oceana, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how the phase out could work and why it matters. (09:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin’s rollback of a plan to phase out single-use plastics. They also remark on the surprising ecological diversity and cleanup efforts of the heavily polluted Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, NY, before commemorating 30 years since the US stopped dumping sewage sludge in the ocean. (04:04)

Saved By the Natural World

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender reflects on how he and his wife Valerie have felt saved by their connection to nature during the COVID-19 pandemic. (02:45)

The Sounds of Mars

View the page for this story

The first successful Mars lander was Viking 1 in 1976, and now, after dozens of missions NASA has finally captured the first ever audio recorded on the surface of the red planet. Host Aynsley O'Neill shares these recordings with Host Bobby Bascomb and explains how Mars' atmosphere alters sound compared to how we experience it here on Earth. (04:19)

New Telescope to Unlock Mysteries of the Universe

View the page for this story

The new James Webb Space Telescope is by far the most powerful space telescope ever built. When the telescope is fully operational, it will be able to see up to a hundred galaxies at once and detect the light emitted from some of the universe's very first stars. It can also look for conditions compatible with life on planets near and far. Dr. Stefanie Milam is the Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science for the James Webb Space Telescope, and she joins Host Steve Curwood to explain how the telescope will help advance science. (21:02)

“How to Love the Stars”

/ Jennifer JunghansView the page for this story

You don't need a $10 billion telescope to take in the wonder of the universe. You can make a simple one yourself, or even just look up with your own two eyes. And for writer Jennifer Junghans, that connection to the stars also represents a connection to her dad. (03:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220708 Transcript

Hosts: Steve Curwood & Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS:

Reporters: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

To help curb the plastic pollution crisis the interior department will phase out single use plastic on public lands.

LEAVITT: Every year 33 billion pounds of plastic enter the ocean. That’s roughly equivalent to dumping 2 garbage trucks full of plastic into the ocean every minute. No place on earth is untouched by plastic. And we’re finding it in our National Parks and other public lands.

Also, NASA launched a space telescope capable of looking into deep space for possible signs of life.

MILAM: So with the James Webb Space Telescope, we’re actually looking at fingerprints of really interesting molecules like water, carbon dioxide, methane. These are all molecules that are signs of life, or even habitability."

That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Getting Plastics Out of the Parks

Plastic fork with seaweed. Single-use plastic utensils are difficult to recycle and can take up to 1,000 years to decompose. (Photo: Ingrid Taylar, Flickr, CC)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood,

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Roughly 40% of all plastic produced worldwide each year is thrown away after just one use.

And while things like plastic forks, straws and bags may be used for only a moment, they can stick around for up to a thousand years before they decompose.

Less than 6% of plastics in the US is recycled, meaning most plastic waste is incinerated, landfilled, or winds up in our oceans.

Seeking to curb such waste, Canada has announced a phaseout of the manufacture and import of common single-use plastic starting at the end of 2022 and culminating by the end of 2025.

Plastic is made from oil and gas, a major resource for Canada which is one of the world’s largest producers of oil.

Still, Prime Minister Trudeau says phasing out single-use plastic is a worthy aim, as the ban would eliminate close to 3 billion pounds of plastic waste over the next decade.

TRUDEAU: Plastic pollution is a global challenge. You’ve all heard the stories, and seen the photos. And to be honest, as a dad it’s tough trying to explain this to my kids. How do you explain dead whales washing up on beaches around the world, their stomachs jam-packed with plastic bags? Or albatross chicks photographed off the coast of Hawaii, their bodies filled to the brim with plastic they’ve mistaken for food? How do I tell them that against all odds, you’ll find plastic at the very deepest point of the Pacific Ocean, 36,000 feet down?

BASCOMB: The U.S. Interior Department has announced a goal to phase out single-use plastics sold and distributed in national parks and other public lands it oversees, but so far the Forest Service under the Agriculture Department has yet to follow suit.

The parks system alone had nearly 300 million visits last year and had to deal with some 70 million pounds of plastic waste.

For more, I’m joined now by Christy Leavitt, Plastics Campaign Director at Oceana. And by the way, we should disclose that Oceana is a supporter of Living on Earth through Sailors for the Sea. Welcome to Living on Earth, Christy!

LEAVITT: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So what exactly does this announcement entail? And how significant is it?

LEAVITT: This is a big announcement from the Department of Interior and the Biden administration. So on June 8th, on World Oceans Day, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland committed to phasing out single use plastic products in our national parks and other public lands overseen by the Department of Interior. So what she did was she issued a secretarial order that calls for the department to reduce the procurement, sale and distribution of single use plastic products and packaging on all Interior Department-managed lands and buildings by 2032.

BASCOMB: Now, the goal here is to phase out plastic by 2032, as you just mentioned, but that's a full decade away. Why does it have to take so long? And what needs to happen between now and then?

LEAVITT: Yeah, well, we are hopeful that they will move quickly to phase out some of the worst, the most problematic, single-use plastics as quickly as possible. Our understanding is that it's going to take them up to 10 years to deal with some of the specific concession contracts that they have. But we definitely know they're interested in moving quickly, and we will be following up to make sure that they do move as quickly as possible.

BASCOMB: Well, what kind of impact does plastic waste currently have in our public lands and waters?

LEAVITT: Just to give you the scope of the problem, as we look at our oceans is that every year, 33 billion pounds of plastic enter the ocean. And to put that in perspective, that's roughly equivalent to dumping two garbage trucks full of plastic into the ocean every minute. And it's not just harming our oceans, but it's also our climate and our health and our communities and our public lands. Basically, no place on earth is untouched by plastic. And we're finding it in our national parks and other public lands. And it has a couple of impacts there. One impact is that nobody wants to look and see single use plastic water bottles or plastic straws or other plastic as they're exploring the beautiful places like Yosemite or the Grand Canyon. And then it's also harmful for the ecosystems there. So not only are there the big pieces of plastic, so the plastic bag, or the plastic water bottle, but it also, plastic breaks up into smaller and smaller pieces called microplastic, that then can get into the soil, can get into the air. That's what we're finding in rain; we're even finding it in human blood and in our lungs, too. So we're finding it everywhere, including in our national parks.

Water bottles for sale in Death Valley National Park, California. Sales of single-use products such as these are slated to end by 2032 in all Department of Interior facilities including in national parks. (Photo: Courtesy of Oceana)

BASCOMB: And to what degree is that potentially a threat to wildlife? You know, the very reason that we're going to these national parks?

LEAVITT: It is a big problem for wildlife. So not only can wildlife get entangled, or ingest plastic, but the same thing is happening with microplastics, where they might be eating it, they might be, you know, breathing it in, those sorts of things, too. So it's a problem for wildlife. And when we talk about our national parks, there's more than 400 different national park units around the country. Some of them are the really big parks, like Grand Teton National Park, and some of them are smaller areas. But 88 of the National Parks are ocean and coastal parks. So they've got a direct impact on what's happening in our oceans as well as our coastal Great Lakes too. So the plastic, if plastic is going out there, it's gonna end up in our oceans. And Oceana did a survey a few years ago, we pulled together a report that looked specifically at what was happening with animals in US waters. And we found nearly 1800 animals -- these were marine mammals, so dolphins, whales, as well as sea turtles -- had been harmed by either ingesting or becoming entangled in plastic in US waters since 2009.

BASCOMB: And of course, those are just the ones that we know about and documented, you can be sure the number's much, much higher.

LEAVITT: That is definitely true. Those are only the ones that people were able to see and observe. But there's a lot more animals that are being impacted by plastic.

Installing additional water fountains, such as this one at Grand Canyon National Park, can help reduce the need for single-use plastic bottles by making it easier for visitors to refill reusable bottles. (Photo: Michael Quinn / NPS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now, of course, plastic is made from fossil fuels, and the production of plastic and the plastic itself is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions that warm the planet. And as we know, climate change is one of the biggest threats to our national parks. To what extent, do you think that was maybe a factor in Interior Secretary Deb Haaland's decision here to phase out plastics on our public lands?

LEAVITT: Yeah, our national parks are definitely faced with extraordinary adaptation challenges. So it's a critical problem. And it's definitely something that the Department of Interior and the Biden administration overall are looking at solutions to the climate crisis. As you mentioned, plastics have a big impact on climate. Almost all plastic is created from fossil fuels. So throughout its entire existence, plastic is creating climate changing greenhouse gases, so it's extracted from, whether it's from oil and gas, that extraction creates greenhouse gases; then the production of plastic creates more; they're transported; they then break down in landfills or they're incinerated or burned. So throughout its whole life, that plastic is creating more and more greenhouse gases. And I don't think most people think of that plastic bottle or that plastic bag as coming from fossil fuels, but it is. And in fact, if plastic was a country, it would be the fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world.

BASCOMB: So how will phasing out single use plastic and the national parks and public lands actually work? What might a visitor see that might be different?

According to Christy Leavitt, every year around 33 billion pounds of plastic enter the oceans worldwide. That’s about two garbage trucks full of plastic every minute. (Photo: Courtesy of Oceana)

LEAVITT: I think some of the things that visitors will see at national parks will be more refillable water stations. So rather than buying a plastic water bottle, there'll be stations at all of our national parks and other Department of Interior sites where you can go and refill your reusable water bottle. There'll also be inexpensive water bottles for sale, so if you didn't bring a water bottle, you'll be able to purchase one right there. And you could use it over again and again. There's already some of that happening at national parks and this will expand it even more. There are a lot of national parks, you can buy food, whether lunch or for dinner. Some of those are cafeteria style. Some of those are restaurant style. And they can move to reusable plates and dishes and cups and utensils. So they'll need to create systems to be able to wash all those dishes. But it will be able to make sure that we're not using single use plastic products in those places.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand many of the gift shops and food vendors in the national parks are actually concessionaires who contract with the National Park Service. So how might this affect them?

LEAVITT: Yes, that is definitely the case where a lot of the restaurants or gift shops are being run by concessionaires. And so they will need to make these changes, they'll need to get rid of unnecessary single use plastic products, whether it's in Yosemite or a National Seashore or another wildlife refuge.

BASCOMB: Christy, what kind of public support or, for that matter, pushback have you seen for this plan to phase out single use plastic in the parks?

Christy Leavitt is Oceana’s Plastics Campaign Director (Photo: Courtesy of Oceana)

LEAVITT: We know that people love their national parks, as we've been talking about a bit here. And we did a survey earlier this year. And we found that 82% of American voters would support a decision by the National Park Service to stop selling and distributing single use plastics at our national parks. So that's a very high level of support, it's bipartisan support. So definite interest in protecting our national parks from single use plastic.

BASCOMB: Christy Leavitt directs the plastics campaign at Oceana. Christy, thank you so much for your time today.

LEAVITT: Thank you. It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- E&E News | “National Parks to Phase Out Single-Use Plastics”

- Read about Secretary Haaland’s order to phase out single-use plastics

- About Canada’s single-use plastics ban

- About Christy Leavitt

[MUSIC: RADIOHEAD “ Fake Plastic Trees” on the bends Capitol Records 1995]

Beyond the Headlines

Republican governor of Virginia, Glenn Youngkin, has rolled back the previous administration’s plan to phase-out single use plastics in the state (Photo: Glenn Youngkin, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org, and he keeps track of what's going on beyond the headlines for us. Hi, there, Peter, how are you doing and what have you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We've got a story about the Commonwealth of Virginia. The previous governor who left office at the beginning of the year, Ralph Northam, had set up the beginning of a scheme to phase out single-use plastics at all state agencies and state universities. The new governor, Glenn Youngkin, rolled some of that back in favor of pushing the idea of plastics recycling, an idea that we've spent many, many years learning does not get the job done.

CURWOOD: So a step forward and, I guess, a step or two backwards, huh?

DYKSTRA: And there was one particularly big program to reduce plastics use and instill other environmental measures at George Mason University, which is a really big commuter school in Northern Virginia outside of Washington, DC. So ambitious was this program, that the new Governor, Glenn Youngkin, recognized George Mason with a Governor's Environmental Excellence Award in March, and the following month, in April, he issued an executive order essentially cutting the legs out of the single use plastics reduction plan.

CURWOOD: All right, Peter, hey, what else do you have for us for today?

DYKSTRA: I've got kind of a stinky story from one of the worst sites in New York City, as far as pollution goes, a Superfund site, the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, the site of heavy industry and rampant dumping for a hundred and fifty years, sewage, all sorts of heavy metals like lead, and there's stuff at the bottom of the canal that's lovingly referred to as black mayonnaise.

Wildlife is thriving in and around Gowanus Canal, in Brooklyn, NY, after over a century of industrial pollution (Photo: Alexander Rabb, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What a place, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but there's a wildlife inventory that's going on in the canal where they're finding everything: birds, sea birds, insects, plants, shellfish, finned fish. But one of the issues and conflicts here is that the citizen based effort to clean up the canal is running into the sometimes rigid programs that EPA sets up for cleanup, and some of the Superfund cleanup efforts are getting in the way of the citizen cleanup efforts.

CURWOOD: But, A, it's helping wildlife and, B, it's getting remediated, so...

DYKSTRA: Maybe a happy ending someday. It's just kind of a gross place, but even in this gross place, there's a concerted effort to clean it up.

CURWOOD: Well, let's take a look back in history now, Peter, what do you see?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, if you're ready for a little bit more smelly news out of the same place, good old New York City. On June 30, 1992, 30 years ago, New York City formally ended its practice, more than 100 years old, of dumping sewage sludge into the Atlantic. There was an uproar in the late 80s in New York and New Jersey about medical waste washing up on beaches, trash, sewage, and all sorts of yucky things. But by that date, June 30, 1992. They became the last American municipality to stop barging its sewage sludge out to the nearby ocean and dumping it.

30 years ago, on June 30th, 1992, New York City became the last city in the US to stop dumping sewage sludge in the ocean. (Photo: bikesharedude, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, better late than never. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon, Peter, thanks a lot.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage that's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Energy News Network | “Virginia Governor Rolls Back Plastics Phase-Out, Seeking to Court Recycling”

- The Sierra Club | “Brooklyn’s Infamous Superfund Site: Also a Wildlife Haven”

- EPA | “Reilly in New York to Mark End of Sewage Sludge Dumping”

[MUSIC: Cage the Elephant “Telescope” from Melophobia on RCA Records and Tapes 2013]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Looking into deep space for signs of life with the James Webb Space Telescope.

Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[MUSIC: Gerry Beaudoin and the Boston Jazz Ensemble, “Willow Weep for Me” on In a Sentimental Mood, by Ann Ronelle, North Star Records]

Saved By the Natural World

Sunlight breaks through the stormy clouds (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Public lands are great places to get out and about as the Coronavirus has meant a lot of isolation.

And nature anywhere helps sanity in these times, says Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

LENDER: What has saved us, Valerie and me, is the Natural World.

We are prisoners in our own home. No one comes. We avoid peopled spaces. Even on our long daily walk we wave from a distance and cross the street. Everyone does. We speak to the mailman through masks. The doctor visits are by phone.

But then all the gulls fly out over the water calling in alarm, the mallards rise up and the fish crows and mourning doves scatter in all directions. Eagle! Powering down the shoreline with a huge fish in her talons, her great wings deceptively slow, the speed incredible, all the wildlife in a rush to get out of her way. Or one of us hollers, “Come quick!” Because the thinnest eyelid of a New Moon has broken through the clouds, vanishing, appearing again and in an instant, gone. Sunsets. Blue-black night. The pinpoint light of stars and a penetrating cold.

We let go. All the unremarked tension of the day lets go. We heal.

Sunset (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Yes, we live in a privileged place but anyone can look up at the sky. Even a prisoner has the free and open space above the prison yard. High above a herring gull crosses over. We ignore the gulls because they are common. Remember then what we so readily forget, that this is a wild animal! Or on your hurried way look east towards where the sun comes up if only for a moment, even if all you can see is the glow. And at the end of an exhausting day turn your head west where all the changing colors linger before they fade. Maybe if you are very lucky (and why not?) low on the horizon will be a V-shaped form, geese like you, heading home.

What else is there to save us? What else to preserve our sanity in the face of all this terror?

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Thanks to Destination Wildlife

- Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife

- Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge 50th Anniversary event, July 23, 2022

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carlos Nunez, “Two Shores” on Brotherhood of Stars, traditional northern Galician]

The Sounds of Mars

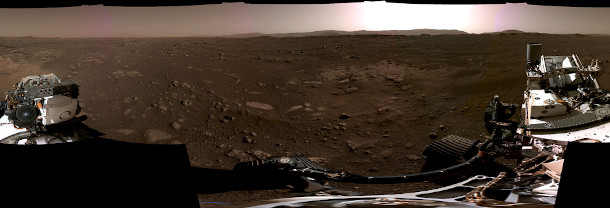

A panoramic view of Perseverance’s landing site on February 18, 2021. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Just ahead in the program we’re going to take a deep dive into deep space but first I want to bring in Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neil who has been listening to sounds of space a little closer to home.

Hey there, Aynsley!

O’NEIL: Hey Bobby

BASCOMB: So, what do you have for us?

Well, NASA spacecraft first landed on Mars with the Viking 1 in 1976. And finally, now after almost 50 years and dozens of missions, the Perseverance rover has recorded the first sounds ever captured on the surface of the red planet.

BASCOMB: Oh, wow, so what does Mars sound like?

O’NEILL: Well, I wasn’t sure what I should be expecting at first – my original impression of what Mars could sound like was based on Ridley Scott’s movie adaptation of The Martian.

[SFX: “THE MARTIAN” AUDIO]

[SFX: STORM]

LEWIS: Visibility is almost zero. Anyone gets lost, home in on my suit's telemetry. You ready?

WATNEY: Ready!

[SFX: STORM]

WATNEY: Commander? Are you okay?

LEWIS: I’m okay!

[SFX: STORM]

CURWOOD: So I’m gonna guess that’s not quite what NASA’s audio sounds like.

O’NEILL: No, not exactly. For one, there’s no sweeping movie score to accompany it. Actually, in the first raw audio captured from Mars, most of what you can hear is just the humming of the Perseverance rover. That’s where the microphone is mounted.

[SFX: FIRST SOUNDS FROM MARS – RAW AUDIO]

O’NEILL: But with a little audio filtering, NASA dialed back those rover sounds, and the wind from the planet comes through a little stronger.

[SFX: WIND ON MARS]

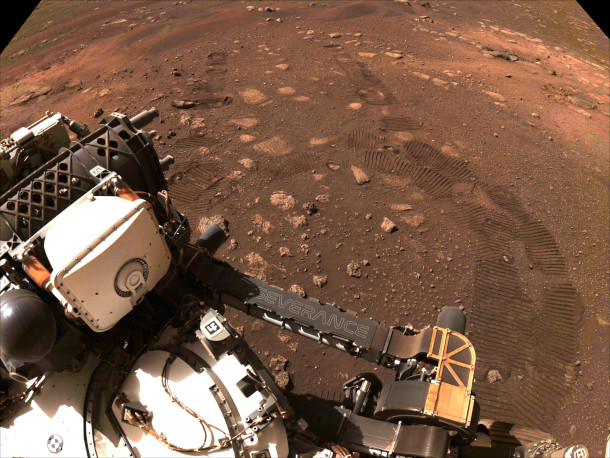

O’NEILL: There’s also the sound of the Perseverance rover rolling across the Jezero Crater just a few Martian weeks into its mission.

[SFX: ROVER DRIVING ON MARS – FILTERED]

O’NEILL: And for the first time, a spacecraft on another planet recorded the sounds of a separate spacecraft when Perseverance used one of its microphones to listen to the Ingenuity helicopter during its fourth flight on Mars.

[SFX: HELICOPTER FLYING ON MARS]

BASCOMB: Now, Mars has a different atmosphere than Earth, so that’s sure to alter how sound waves move, right?

In this photo, the Ingenuity helicopter is deployed from underneath the Perseverance rover. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O’NEILL: Yeah, the atmosphere of Mars is roughly 96% carbon-dioxide, and those molecules absorb a lot of higher pitched sounds, so only low pitch sounds would be able to travel long distances on the red planet. So, the sounds of some city birds here on Earth

[SFX: EARTH BIRDS]

kind of get lost on Mars.

[SFX: MARS BIRDS]

O’NEILL: Also, because the atmosphere is around 100 times less dense than Earth, there are fewer atoms for the sound waves to vibrate through, so volume would be quite a bit softer than here on Earth. The sharp sound of a bike bell

[SFX: EARTH BIKE BELL]

gets muffled on the red planet.

[SFX: MARS BIKE BELL]

O’NEILL: To top it off, Mars’ average surface temperature hovers around negative 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

BASCOMB: Wow, that’s cold – what does that do to the sound?

O’NEILL: All these factors work together to make the Martian speed of sound a little slower than on Earth, where it moves at around 340 meters per second. And on Mars there are actually two speeds of sound: low-pitched noises travel at around 240 meters per second, while higher-pitched noises clock in at 250 meters per second. This is because the carbon dioxide molecules in the atmosphere vibrate too rapidly at the higher frequencies, and don’t have the time to slow down.

BASCOMB: So, any person on Mars would have to be in a space suit to breathe, of course, but let’s just imagine that two people were able to talk to each other – what would that sound like?

O’NEILL: Well, that would depend on the distance between the two people, but overall, sound would be quieter, and it would take those people a little bit longer to hear each other.

BASCOMB: So, on an alien planet, we would even sound a little alien.

The Perseverance rover is now moving up the slope of the Jezero crater, looking for new rock samples. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O’NEILL: Yep, and NASA even has a tool that will allow you to filter your own Earth audio, so you can hear what it would sound like on Mars.

For example, let’s wrap up by listening to a familiar song. Maybe the Living on Earth theme tune?

BASCOMB: Sure, go for it!

[SFX: LOE THEME, MARS VERSION]

BASCOMB: And by the way the Perseverance Rover is now rolling up the slope of the Jezero crater. It will collect a group of rock samples that scientists are hoping might contain hints of ancient life on the planet’s surface.

Related link:

Find out more about the audio captured on Mars at NASA’s website

[MUSIC: Women Of the World, “Latibonit” on Makana, traditional Haitian folk song/arr. Deborah Pierre with Annette Philip, Sashank Novaladi, self-published.]

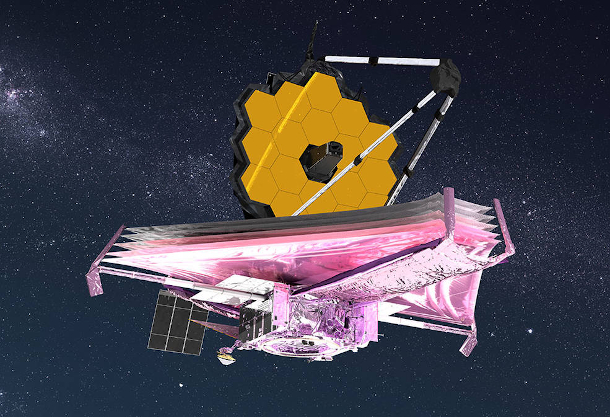

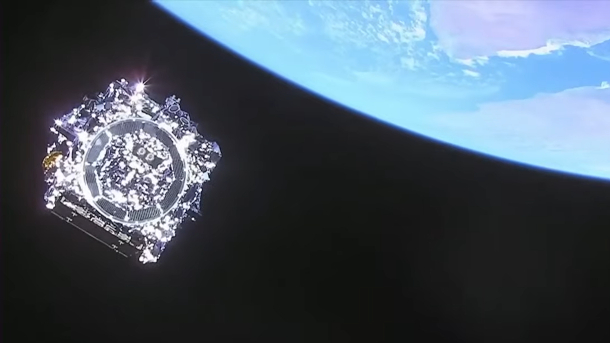

New Telescope to Unlock Mysteries of the Universe

An artist’s rendering of the James Webb Space Telescope, with the multilayered sunshield stretched out beneath the observatory’s honeycomb mirror. (Photo: Adriana Manrique Gutierrez, NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: We all experience gravity anytime we drop an object. But science has yet to explain just how gravity works. Is it a force? Is it a curvature in space time, as Albert Einstein suggested? And along with the mystery of gravity there is also so-called dark matter, which seems to occupy more than 80 per cent of the universe, but we still can’t see it or explain it. Well, two recent amazing developments may help bring some answers. A subatomic particle called the W Boson was discovered back in 1983 but earlier scientists reported new measurements of its mass that upend the conventional rules of physics, rules by the way, that have failed to explain gravity and dark matter. Meanwhile on last Christmas Day the massive James Webb Space Telescope was launched into an orbit a million miles above Earth and will start sending back pictures by this summer.

The Webb Telescope can look far deeper into space and further back in time than its predecessor, the Hubble Telescope. Not only will the Webb Telescope see stars born much closer to the so-called Big Bang beginning of our universe, its higher resolution images of super novas and galaxy motion might provide more insight into the phenomena of dark matter and gravity. And because it looks at infrared light it will also help in the search for signs related to life on other planets, both near and far. Here to tell us more about the extraordinary Webb telescope, is Stefanie Milam, the Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science at NASA. Stefanie, welcome to Living on Earth!

MILAM: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So Stefanie, before we begin talking in detail about this, explain to somebody who really maybe hasn't heard much about this, what kind of telescope we're talking about here.

MILAM: So the space based telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, is called the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope. So this is NASA's next big astrophysics space telescope that we launched on Christmas Day. And it is going to be looking for the first stars and galaxies across the universe.

CURWOOD: So it's gonna take a look at deep space and way back in time, but also I understand it can look in the local neighborhood at some things.

MILAM: Absolutely. So that was my role on this project actually, was to make sure that not only this extremely sensitive telescope that's studying you know, the farthest reaches of the universe can study first stars and galaxies and planets around other stars, but we can look at things much closer to home. We wanted this to be an all-purpose general observatory that the entire astronomy community could use the way that we've used the Hubble telescope to look at things like Mars or Jupiter or Saturn. But we also study things like distant stars and galaxies and planets around other stars. So we wanted James Webb Space Telescope to offer the same sort of capabilities. And it's extremely hard to look at things in our own neighborhood because they're so bright. And also they move with respect to the other stars, our whole solar system is moving constantly. So being able to track something moving across the sky with respect to background stars, and galaxies, is a whole different capability that a lot of telescopes, especially smaller ones aren't necessarily designed to do.

CURWOOD: The Hubble Telescope still makes remarkable scientific discoveries regularly. I think, just recently, it spotted the most distant star ever detected so far in the universe. So what sets the James Webb Space Telescope apart from the Hubble?

MILAM: So that was an amazing discovery that just happened and a very exciting one. Seeing the farthest star that we've ever been able to observe with the Hubble Space Telescope only motivates and excites the astrophysics community to what the opportunities the James Webb Space Telescope is going to enable. So we have an extremely sensitive telescope, we're 100 times more sensitive than the Hubble Space Telescope at infrared wavelengths. So what the James Webb Space Telescope is actually optimized for is infrared light. So it's like night vision goggles, we're seeing these tiny little faint heat signals across the universe, from when the first stars and galaxies were actually born, right after the Big Bang. So the James Webb Space Telescope is going to look even further back in time than what the Hubble Space Telescope because it's looking at these longer wavelengths of light, because the universe is expanding, and that light is moving away from us, it stretches the light that we would see, for example, with our own sun, or stars in our own galaxy, to longer and longer wavelengths. And so by looking in the infrared with an even more sensitive telescope than the Hubble, we'll be looking at stars that are even older or even further back in time. So, really exploring that sort of infant years of the universe is something that's very exciting, especially for the astrophysics and cosmology communities.

Scientists observe the main mirror assembly of the James Webb Space Telescope in November 2016. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Stefanie, please give us a brief overview of what your role is on the Webb telescope project. I mean, what were you working on before the launch on Christmas Day? And what are you doing now that the telescope has reached its orbit?

MILAM: So, I've been working on this project for about a decade, they brought me on to make sure that this space telescope can study things in our own solar system. So, things like Mars, asteroids, comets, Pluto, or even things like the rings of Saturn, or tiny little moonlets that are yet to be discovered in the giant planets or the ice giants in the outer solar system. And even if we discover something like the next planet nine, the James Webb Space Telescope is something that would be ideal to use to study those types of objects. And so it was a challenge to bring solar system science into this realm of astrophysics space telescopes, because they're so sensitive, and they're so extremely big and massive that making the move across the sky to track a comet moving or an asteroid flying across the sky is something pretty hard to do. And so it's a whole new capability that we had to make sure that we wanted to have for the James Webb Space Telescope. And so that was my role. And leading up to the launch, it was to make sure that we had one the capability to study things in our own solar system, so tracking moving targets, making sure we could look at extremely bright objects like Mars or Jupiter, and also that we needed to. So making sure that the science was actually something that was of interest to the community. So that was a lot of engagement with the planetary science community but also with the project itself to make sure that the technical capability was there.

[MUSIC: David Bowie, “Space Oddity -1999 Remaster” on Best of Bowie, Parlophone Records Ltd.]

CURWOOD: My guest is NASA scientist Stefanie Milam, and our conversation will continue right after the break. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Where we’re going, we don’t need roads!

— NASA Goddard (@NASAGoddard) April 14, 2022

To see back in time, @NASAWebb looks in infrared wavelengths, which we feel as heat. @NASAHubble sees visible light, with infrared and ultraviolet abilities. The telescopes will work together as we #UnfoldTheUniversehttps://t.co/Ji53Tq2GQx pic.twitter.com/J5oJZtpCFI

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Liquid Saloon “Bear Walk” Single, Raw Tapes Records]

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood, and I’m back now with NASA scientist Stefanie Milam, talking about the new James Webb Space Telescope. Stephanie, thinking about our near space community here, our solar system, how does this ability of the Webb telescope to look at infrared open the door to some interesting discoveries? I mean bbviously you don’t know what you don’t know, but whaddya think you might want to know?

MILAM: We already have some ideas of things that we really want to study with this telescope in our own solar system. So at these wavelengths, we have access to looking for fingerprints of molecules of interest. So every molecule, if you think of your generic chemistry from high school, every molecule has its own fingerprint the same way you have a unique fingerprint with respect to me. And so what we do is we look for these fingerprints of different molecules to study the chemistry of a particular environment. So with the James Webb Space Telescope, we're actually looking at fingerprints of really interesting molecules, when it comes to things like looking for habitable worlds or oceans in our solar system, or just understanding what's actually happening in the extremely different and unique environments, from planet to planet, as well as moon to moon, just as we look across our own solar system. So some of the molecules of interest are things like water, carbon dioxide, methane. These are all molecules that should be ringing a bell of things that are very key signs of life, or even habitability.

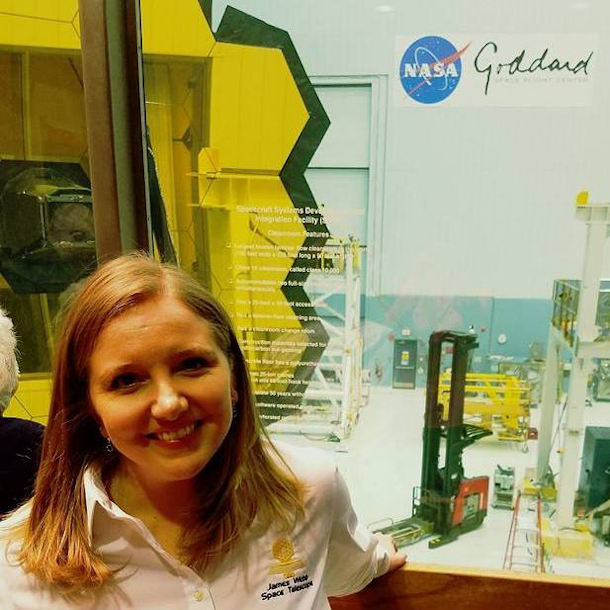

Stefanie Milam, inside the cleanroom where the James Webb Space Telescope resided. (Photo: Courtesy of Stefanie Milam)

And so as we explore our solar system, and we get new spacecraft going to Jupiter, or to Titan, one of the moons of Saturn, or even one of these moons around Jupiter that we think has a subsurface ocean, it's called Europa, we think there's all kinds of extremely interesting environments that could be sustainable for something like life. And so understanding what that chemistry looks like, understanding what the composition of these bodies are, and how that may or may not change is something extremely interesting for planetary science and exploration. And so the James Webb Space Telescope is gonna sort of reveal a lot of these details of these objects in our own solar system that we've never been able to really study with this kind of sensitivity. It helps us provide the right information and level of detail as we send the next generation of planetary explorers out there. So making sure we have the right instrumentation to look for water-like chemistry, or aqueous chemistry. Or if there isn't water there, what is there? Then we can start optimizing our instrumentation so that we're sending the right things there at the right time. This actually applies as we look at other planets around other stars as well. It's the same chemistry that we're gonna be looking at, in these planets called exoplanets, because they're beyond our own solar system. So we're gonna be studying them in the same way that we study the planets in our own solar system. So now we have a comparison that we can actually understand something that's so far away, maybe not quite tangible yet. But we can still get a better understanding of what those planets are made of. And maybe they have an atmosphere, maybe they have volcanoes, maybe they have giant ice oceans. These are the kinds of things that the James Webb Space Telescope gonna help reveal.

CURWOOD: And then you're gonna look to see what exosolar planets, planets around other stars, see how they might match these. And of course, you already have the data for Earth, so you can see if any one of them exactly or closely matches us.

MILAM: Yeah, so the idea is looking for something like an Earth 2.0, is something that, you know, humankind has this innate sense of, you know, discovery that we want to know if there's life out there, if there's another world that we could live on, or you know, travel to at some point. And so searching for something that looks like Earth is of key interest. Plus, it gives us a target for the extremely large number of objects. Now, we're over 5000 exoplanets known today. And so it gives us sort of a short list of objects to start studying, especially when it comes to key questions of things like habitability. So we're not gonna be seeing life itself with the James Webb Space Telescope, we're looking for these key fingerprints of specific molecules that may provoke some sort of unique chemistry happening. And that's some sort of process that's making the chemistry of that planet look different. And that could be because of life. It could be because of geologic processing, so volcanoes, or giant sand storms, or weather, or maybe there's crazy clouds in the atmosphere, like on Venus. These are the kinds of things that we're gonna be studying so that we get a further understanding of these planets, maybe get the list a little bit shorter, even still, with the James Webb Space Telescope, so that the next generation of space telescopes or Explorer missions will be able to study them in even more detail.

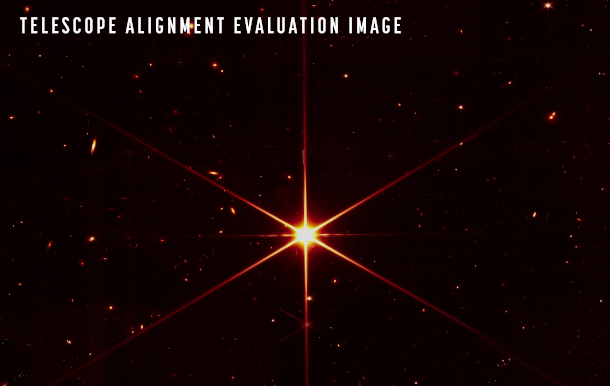

This photo, taken during the alignment process, shows that the James Webb Space Telescope’s optical performance is on track to meet or even exceed the goals it was built to achieve. The image intended to focus on the bright center star, but the sensitivity of the telescope is such that the background galaxies and stars are also visible. (Photo: NASA, STSci, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So now, what's the timeline for this project? For a moment, let's go back to when it was first conceived, and then tell me how long this mission is expected to last.

MILAM: So going all the way back to the early 90s was when a group of scientists decided that the discovery space that Hubble has opened up was just not quite good enough. And they knew that they were gonna hit a limit. And so this actually came out of an experiment that happened with the Hubble Space Telescope, where they basically stared at a blank piece of sky for a considerable number of hours. And what they found was not blank sky, they actually found thousands of galaxies within something that's the size of your fingernail, if you stuck it up on the sky. Thousands of galaxies, but what happened was, is when they started analyzing the data and seeing how far back in time, they could see, what was the oldest galaxy that we could study with the Hubble Space Telescope, they were blown away about the discovery space that Hubble actually had and the capability that it had. But there was a limit, there was a wall. We couldn't quite push any further. And so to get further, we had to have something much bigger, much more sensitive, and something that actually was optimized for infrared wavelengths. And so that’s sort of how JWST evolved, from, you know, the Hubble Space Telescope to this massive infrared telescope. You know, this beautiful gold mirror, this crazy boat looking structure underneath it to keep it nice and cold, and putting this telescope a million miles away from Earth so that it could stay cold and operate. Putting it that far away, unfortunately means that we do have a limited life mission, because we can't send astronauts there currently, to go and service the telescope the way, that we've serviced the Hubble Space Telescope for decades. So what that means is we had to carry a certain amount of fuel to operate the telescope, to do things like offset momentum, to make sure we stay in the right place in its orbit. And also just to control the telescope. Fortunately, we had a very beautiful launch with Arianespace, we were on a rocket that launched out of French Guiana that was provided by the European Space Agency. It sent us on a beautiful trajectory, a million miles away from Earth. And we were actually able to conserve a lot of fuel, which means that our mission lifetime went from a ten-year that we were projecting at launch to something that looks more like 20 years of operations now.

The James Webb Space Telescope, seen shortly after separation, as photographed from the upper stage of the Ariane 5 rocket. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So there have been some calibration and alignment photos from the James Webb Space Telescope already. But when are we gonna start to see the first scientific photos, both the stuff that you care about nearby and the deep space stuff?

MILAM: Well, I will honestly tell you that all of the calibration images we've seen so far has been absolutely amazing and astonishing for me and the whole project. And every single day, we get to see more and more of these. And it's all the more impressive of how well this observatory actually works and really exciting to think about what it's going to do for us. But the first science images are actually going to be released in the summer. They'll all be released at once. There'll be some probably NASA event going on. And some online, you know, you can log in and follow along with us. But as soon as that happens, it's basically the initiation of science operations for the James Webb Space Telescope. So we already have our first year of science observations already planned. It includes everything from solar system observations, deep studies of the distant universe, studying planets around other stars, watching planets and stars being formed in their own stellar nurseries in our galaxy and in the universe, how galaxies merge together, how they evolve, how stars evolve, what happens when they die, all kinds of really amazing science, that I don't know if there's a way to prioritize it as far as enthusiasm. But I think it's all gonna to be exciting, and we're gonna rewrite the textbooks.

Stefanie Milam, outside the cleanroom where the James Webb Space Telescope resided. (Photo: Courtesy of Stefanie Milam)

CURWOOD: Stefanie, what are you personally most excited to study with the data we're gonna be getting from the James Webb Space Telescope?

MILAM: Well, so I'm a cometary scientist. So I study comets in our solar system. And I also study interstellar objects, which are new things that we've discovered in our solar system. So these are comets or asteroids that come from other planetary systems. So what we learned from comets is basically, how the solar system actually formed. What was the process? What was the chemistry like? How did something like Earth, with liquid water on its surface, all the right ingredients to have biology, biochemistry, how did that all get here in the right place? The right time, the right composition? What were those ingredients? And if those ingredients are something that are ubiquitous across our whole galaxy or other planetary systems, then that's something that will give us key insights into what kind of planets, what kind of planetary systems, or even what kind of star forming systems or regions we need to be looking for in our search for this Earth 2.0. So comets are basically, you know, the relics or fossils of when our solar system formed. So by studying them, we learn a lot about all of those key ingredients, all of the processing that happened during the formation of the solar system. And so the James Webb Space Telescope is actually very accessible to studying these objects.

CURWOOD: But wait, you said that there are some comets from other solar systems? What about that? How the heck did they get here? And what do they tell us?

MILAM: Yeah, so we now have discovered two interstellar objects. One of them looked like an asteroid or a spaceship to some people. It was called ʻOumuamua. And the second one actually looked like a comet, and it was called Borisov. We expect with all the new surveying telescopes that are coming online, such as the Rubin Observatory down in South America, as well as a number of other large surveying capabilities that are being built and getting ready to be operational, we're gonns to discover more and more of these kinds of objects. So these are basically the the comets or asteroids that whenever another planetary system is forming, maybe they collided with another one. And it bumped it off course, such that it got ejected from its own planetary system. We've anticipated and expected this is something that happens with our own small bodies in our solar system. But I don't know that anyone ever really anticipated that we'd actually discover one from another planetary system in our own solar system. So it was extremely exciting for this discovery to actually happen a few years ago.

Stefanie Milam is NASA’s Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science for the James Webb Space Telescope. (Photo: Courtesy of Stefanie Milam)

And now that we found two, that are completely different from one another, your imagination goes wild. What does this mean? What is this telling us about one, not only the planetary system that they formed in, but what does it tell us about the journey that that object had to have going from its planetary system through space, and the harsh conditions of radiation from nearby supernova, or stars colliding with each other, or new planetary systems forming or whatever, all the way on its journey to get to our own planetary system. So there's all kinds of things that are really interesting about these objects. We're so excited for the next discovery of one, and all hands are on deck to observe it with every every telescope on Earth and in space.

CURWOOD: If you discover it, is it gonna be called the Milam Comet?

MILAM: Yes.

CURWOOD: Woah!

MILAM: Well, so far, comets are named after their discoverers. And so far, interstellar objects are named for their discoverers. So we'll see.

CURWOOD: You haven't discovered one yet, but...

MILAM: I haven't discovered one yet. But I will say asteroids also get designated name. And so I do have an asteroid named after me.

CURWOOD: Oh, and that one is called?

MILAM: Milam.

CURWOOD: How big is Milam?

MILAM: It's small. I think it's about 10 meters is what they're predicting.

CURWOOD: So about 30 feet wide.

MILAM: Yeah, not very big. It's in the main belt. It's, it's a rock. But it's my rock. So it's a really cool rock.

CURWOOD: Stefanie Milam is the Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science for the James Webb Space Telescope. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MILAM: Thank you so much for having me. This was a lot of fun.

Related links:

- Scientific American The James Webb Space Telescope Could Solve One of Cosmology’s Deepest Mysteries

- Read more on the James Webb Space Telescope at the official NASA site

- Stefanie Milam’s biography page

- The James Webb Space Telescope on Twitter

- Stefanie Milam on Twitter

[MUSIC: David Bowie, “Space Oddity -1999 Remaster” on Best of Bowie, Parlophone Records Ltd.]

“How to Love the Stars”

Jennifer Junghans observes that the stars are “light memories from the same stars the first hominids looked up and saw.” (Photo: Graham Holtshausen on Unsplash)

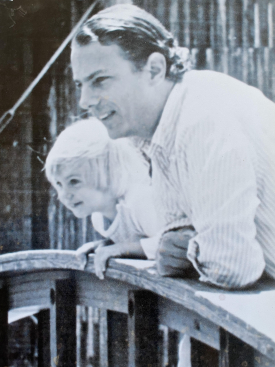

BASCOMB: Well, you don't need a $10 billion telescope to take in the wonder of the universe. You can make a simple one yourself, or even just look up with your own two eyes. And for writer Jennifer Junghans, that connection to the stars is also a connection to her dad.

JUNGHANS: It’s a muscle memory now, to look up and search the night sky. Even if just for a moment to return to the time when I was young and my dad was too, him bursting with enthusiasm to unlock for my sister and me all the magic that lived in those stars.

He’d fiddle with the Dobsonian telescope he built, making endless minute adjustments. At last, he’d usher us to peer through the eyepiece at the magnified stars before Earth rotated them out of view.

A homemade Dobsonian telescope (Photo: ECeDee, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

He’d name the stars and point upward connecting the dots for us into constellations that I could never quite make out. Always with an urgency, as though his work as a father wouldn’t be done until he taught us how to love the stars.

I think he wanted us to know how to lose ourselves in the mysteries of the twinkling sky. To believe in possibilities beyond what we know. To accept with certainty, we’re supposed to be here even though we don’t yet understand how we fit into the grand scheme of the universe.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “The Onyx”]

Beyond the dazzling beauty, I fell in love with the constancy of the night sky. All the loss in our lives, the dreams that never came to be, the loneliness … I forget it all when I stargaze and bathe in the galaxy.

The signatures of light we see are the museums of these gaseous, fiery balls that have burned and pulsed for millions sometimes billions of years. They’re light memories from the same stars the first hominids looked up and saw. The same ones that lit the sky when dinosaurs roamed.

A young Jennifer Junghans with her dad, who taught her “how to love the stars” with a homemade telescope. (Photo: Courtesy of Jennifer Junghans)

The time continuum is almost unfathomable, this stitching together of all who came eons before us and all who will come after, bound in the accumulated history of the stars. They are the universal witnesses. And in this way, nothing is forgotten and everything still exists.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “The Onyx”]

I find great comfort in that as my dad’s memories dim. He’s transitioning like a giant star about to expire, exploding into a luminous, spectacular supernova. In the same way, his energy will outlast his physical body. I wonder where it will go? Could it disperse into the universe and form a new star that burns for another billion years?

It’s a legacy I think my dad would love. And it’s the one I’ll hold on to. Believing that when I look up into the night sky, it’s my dad’s light I’ll see.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “The Onyx”]

BASCOMB: That's writer Jennifer Junghans with her essay, "How to Love the Stars."

Related links:

- Watch: Step-by-step making of a Dobsonian telescope, with amateur astronomer John Dobson

- Jennifer Junghans’ website

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “The Onyx”]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Hannah Richter and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Special thanks to the Stuart B. McKinney Wildlife Refuge

Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth