July 22, 2022

Air Date: July 22, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Biden Punts on National Climate Emergency

View the page for this story

West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin blocked passage of a half trillion-dollar measure in the Build Back Better Bill to address climate change. So, President Biden responded with more executive actions on climate including boosting offshore wind, but he stopped short of declaring a national climate emergency as some in Congress have urged. Vermont Law School professor and former EPA Regional Counsel, Patrick Parenteau joins host Steve Curwood for more. (10:24)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra joins host Bobby Bascomb to discuss Saudi Arabia’s investment in the U.S. petrochemical industry. They also look at why the Great Salt Lake in Utah has reached its lowest level ever recorded. And from the history books, a look back at the origin story of a popular legend: the Loch Ness Monster. (04:52)

Blue Trees Against Deforestation

View the page for this story

Artist Konstantin Dimopoulos talks with host Bobby Bascomb about his project to paint tree trunks bright blue to raise public awareness about deforestation. (06:56)

Big Dog, Soft Mouth

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

An elephant seal could easily crush most any bird but Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, watches as one instead gives repeated warnings to two irritating petrels. (04:20)

BirdNote®: Identify Bird Sounds On Your Phone

/ Ariana RemmelView the page for this story

BIRDNOTE®: IDENTIFY BIRD SOUNDS ON YOUR PHONE: Even if you can’t tell a cardinal from a crow birding apps can make a birder out of anyone. BirdNote's Ariana Remmel shares details about tools for the novice birder. (02:01)

Spectacular Images From Deep Space

View the page for this story

The James Webb Space Telescope is the most powerful observatory ever launched into space – and now, after six months of the mission, NASA has publicly released the telescope’s first full-color images and data. Stefanie Milam, the Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science at NASA, joins host Steve Curwood to give an update on the first images. (19:02)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220722 Transcript

Hosts: Steve Curwood & Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Konstantin Dimopoulos, Mark Seth Lender, Ariana Remmel, Stefanie Milam

Reporters: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. With heat waves ravaging the northern hemisphere this month, President Biden promises to act on climate even if Congress won’t.

BIDEN: As President, I have a responsibility to act with urgency and resolve when our nation faces clear and present danger. And that's what climate change is about. It is literally, not figuratively, a clear and present danger.

CURWOOD: Also, the new Space Telescope is a game changer.

MILAM: We are in a whole new era of astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science, where now we're able to know that oh, a planet around another star has clouds and weather the same way that we do on earth. It's really hard for me to fathom how we can do this so well.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Biden Punts on National Climate Emergency

Over the past two decades, warmer springs and longer dry summers amplified by climate change have resulted in drier soil and vegetation, increasing the length and damage of the wildfire season. To paint a picture, NOAA estimates the total costs of wildfires in 2017 and 2018 to be more than $40 billion. (Photo: Felton Davis, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Federal election commission data show West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin has taken more money from oil and gas interests than any other member of the current Congress. Mr. Manchin recently blocked passage of a half-trillion-dollar measure to address climate change. So, President Biden hit back. Although, the president didn’t go as far as calling a national climate emergency, disappointing some in congress who have called for such action. But, speaking in the blazing sun during a heat wave at a green energy factory in Massachusetts on July 20, he didn’t rule it out for the future.

BIDEN: As president, I have a responsibility to act with urgency and resolve when our nation faces clear and present danger. And that’s what climate change is about. It is literally, not figuratively, a clear and present danger. The health of our citizens and our communities is literally at stake. The U.N.’s leading international climate scientist called the latest climate report nothing less than “code red for humanity.”

CURWOOD: Unless democrats can gain more seats in the November elections as to be able to bypass Joe Manchin, President Biden will have to ramp up executive actions such as those he mentioned for more windfarms and resources for heat waves.

BIDEN: In the coming days my administration will announce the executive actions we have developed to come back to some urgency. We need to act. Just take a look around. Right now, 100 million Americans are under heat alert. 100 million Americans. 90 communities across America set records for high temperatures just this year, including here in New England, as we speak.

My message today is loud and clear: Since Congress is not acting on the climate emergency, I will.

— President Biden (@POTUS) July 20, 2022

And in the coming weeks my Administration will begin to announce executive actions to combat this emergency.

CURWOOD: For more, I’m joined now by Vermont Law School Professor Patrick Parenteau, a former regional counsel for the EPA. Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth.

PARENTEAU: Thanks Steve, good to be with you.

CURWOOD: Pat, why do you think that President Biden punted on declaring a national emergency for the climate right now? It's really hot. We're about to go into storm season, he would look good, I would think, to the world and the general public.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I was surprised, I really did think that we were going to hear an announcement that he was going to declare a national emergency. The heat waves that are baking the country would have would have provided a phenomenal backdrop for that. I have to believe that two things were at work at least: one, I think the lawyers in the administration and in the White House are concerned about how far they can really go using this declaration. There's not a lot of law on this question. And so, I'm sure the lawyers are saying before we start making bold pronouncements, we better think this through. One thing is the legal vulnerability to making this declaration, the other is raising expectations yet again, which Biden has been doing. He did it in the campaign, he did it in the first 100 days, he's been raising expectations about what he was going to be able to do on the climate. And he really hasn't been able to deliver. That's not all his fault. In fact, most of it isn't his fault. Events have foiled him, his own party, Mr. Manchin has foiled him. But the point is, he hasn't delivered. And his approval ratings are in the tank, not just because of climate, of course, it's mostly inflation and other things but climate is a part of it. So, probably some of his political advisors are saying, let's be careful about making bold promises that we really are not sure we can keep. So, there's a debate going on is my guess.

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk about that. I mean, what would the declaration of a national climate emergency mean, a national emergency here? I mean, talk to me about the real limits to the president's power, if he makes that declaration, what could he, what could he not do?

According to NOAA as of July 12, 2022, 44.98% of the U.S. and 50.61% of the lower 48 states are in drought, limiting the water availability for productive farms. (Photo: Dasroofles, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Yeah, we don't know definitively what the limits of this power are, we do know that there are by some estimates, about 150 different laws that are triggered with this declaration. Of that number, though, probably only a handful, are really the most relevant to the climate crisis or the climate emergency. And of those, some are easier than others to do. And some have unknown legal vulnerabilities. So, the ones that he can do pretty clearly are things like limiting United States government funding of fossil fuel development in other countries. We do a lot of that through the Export Import Bank, the World Bank on which we sit and other international monetary funds. So, one thing he could easily do, well at least legally easily do, would be to say, we're no longer going to underwrite fossil fuel development around the world. Another one, he can direct his military. He has tremendous authority over the military establishment, which is huge, and has a huge carbon footprint. He can turn the military into a model for energy efficiency for electric vehicles, for building retrofits and pour lots of money from the military budget into things that would promote renewable energy.

CURWOOD: You suggested declaring a national emergency, he could really mobilize the military. But even without that, he's commander in chief, how much could he do for the climate using the military?

Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who took more campaign cash from the oil and gas industry than any other senator, blew up the Democratic Party’s plan to fight climate change.

— The New York Times (@nytimes) July 15, 2022

Here’s a look at how the plan unraveled as the Earth continues to warm. https://t.co/js6zCTQvg9 pic.twitter.com/DsXbOzG8XY

PARENTEAU: I think he could do a lot. Probably the biggest thing he could do with a declaration is move a lot of the money around. I mean the Pentagon gets one of the biggest budgets in the United States. And he can ask the military or direct the military to use their procurement authority to prioritize electric vehicles, for example, to retrofit military bases with renewable energy, solar and wind, more efficiency in appliances. But if he wanted to make a really big statement, the declaration would probably help him do that.

CURWOOD: Some people have called for suspending oil exports or stopping oil and gas leasing. To what extent could he do that with a declaration of national emergency?

PARENTEAU: He has quite a bit of authority under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act to suspend leasing in places like of course, the Gulf of Mexico where a lot of the leasing occurs, or in the Arctic, where some significant leasing is occurring. And he can do that. There could be and there would be litigation over whether the lesees, the oil companies, are entitled to some form of compensation, if he were to do that, but that's a separate sort of legal question. It isn't going to stop him legally from doing that, so that would probably be one of the major ticket items that he could do having declared a declaration. And then of course, he'd have to see how that action fared when it was challenged in court. Another one that people have pressed him on, a really big one would be to ban oil exports, not gas exports, but oil exports. We are a net exporter of both oil and gas. That's, that's a relatively recent development. And the thing there is that in order for him to ban oil exports, he has to make some key findings. He has to find that the current situation with oil is causing price spikes in the United States, he has to show that if he doesn't ban exports it's going to have a disproportionate impact on the American Labor Workforce. So that one, I would say is in the category of questionable in terms of how the United States Supreme Court would ultimately view the exercise of a ban on oil exports. But that is something he could do.

CURWOOD: And I take it that there's no talk of banning the export of natural gas, because it would betray the Europeans that have been working so hard on this problem between Mr. Putin and the Ukraine.

PARENTEAU: That's right, a ban on export of gas would, would really impact Europe, which is struggling already with its need and its reliance on Russian gas. And of course, that's where Putin is getting the money to fund his war machine. So, the gas issue is much more complicated, I would say, than the oil issue.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think that limiting oil exports would rattle Wall Street?

On July 20, 2022, President Biden visited the Brayton Point Power plant on Mount Hope Bay in Somerset Massachusetts, pictured above. It was once a coal fired power plant, but it closed down in 2017 and is in the process of becoming integral to the production and distribution of wind energy. (Photo: Shaun C. Williams, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Oh, I think it would definitely rattle Wall Street and the banks to think that the assets that the companies they're lending money to are now at risk from this presidential declaration. That would be a huge signal to the financial markets that their investments in fossil fuel are at risk.

CURWOOD: So Pat, what would be the actual difference if say President Biden decided to invoke a national emergency for the climate emergency? How close might this get us to slashing 50% of emissions by 2030 like he promised?

PARENTEAU: I don't think it'll get there. It's going to be very important symbolically, to the world, for the president to do this. And it'll give clear direction to his agencies, although he's done that in the past, but even perhaps, up the ante for the agencies to get on with the things that they can do under existing law. But in terms of can it accomplish the pledge that we've made to the Paris Agreement to reduce our emissions by 50% by 2030, he can't get there without Congress. Every analyst that's looked at this, the Rhodium Group that studies this stuff, minutely. Everyone that's looked at this has said a major investment of federal funding is going to be required to jumpstart the renewable energy industry, the electric vehicle industry, the upgrade of the grid that we need, that's just going to require the $500 billion, at least, that the president had in his Build Back Better Bill, and probably a lot more than that. In fact, most of the financial analysts are talking about the U.S. should be expending on the order of a trillion dollars a year if it wants to accomplish net zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050. So, we absolutely have to have congressional action here.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a former Regional Council for the EPA and a Professor at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PARENTEAU: Thanks for having me, Steve. Appreciate it.

Related links:

- Learn more about Biden’s executive action Fact Sheet

- Reuters | “Biden Stops Short of Declaring Climate Emergency, Takes Steps on Wind Power”

- The Washington Post | “Biden to Issue New Climate Policy, Vowing to Act If Congress Doesn’t”

- The Guardian | “Biden Under Pressure to Declare Climate Emergency After Manchin Torpedoes Bill”

[MUSIC: Martha And The Vandellas “Heat wave”, from Heat Wave on Gordy Records 1963]

BASCOMB: Coming up – An artist paints trees blue to raise awareness about deforestation.

Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[MUSIC: Dean Evenson’s” Peace Like a river”]

Beyond the Headlines

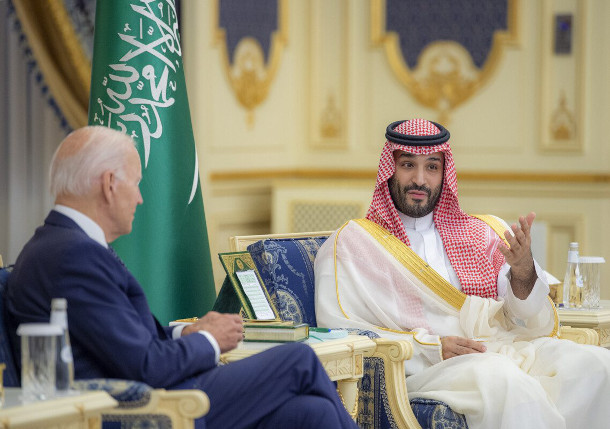

President Joe Biden meets with Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at Alsalam Royal Palace in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, on July 15. (Photo: Middle East Monitor, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth – I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. And it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Bobby, there's a pretty big side note to President Biden's recent visit to Saudi Arabia. There was a lot of fuss over that with the Saudi's human rights record, and whether or not in the era of the climate crisis, that the president should be going and making nice with a country over oil. And that seems to be exactly what he did. But even if that didn't happen, the Saudis are heavily invested in petrochemical plants, the part of oil and gas that make our plastic, all over the U.S. in Texas, in Louisiana, in Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, Saudi Arabia is the world's second largest producer of oil after only the United States. So, it stands to reason that they would have interest in, you know, petrochemical industry. That's sort of the, the oil industry's Plan B, if we're not going to burn enough oil in our gas tanks.

DYKSTRA: Business is business. The oil and gas industry is smart enough to see the writing on the wall, and fossil fuel production for energy is on the outs. Maybe not this year, maybe not 20 years from now, but eventually, if we're to be serious about dealing with climate change and keep places like Portugal from turning 117 degrees Fahrenheit, which it did last week.

BASCOMB: Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Salt Lake City and the Great Salt Lake; the lake is a beautiful place. I was out there in the 1980s, when the lake had reached record high levels due to record snowfall the previous few winters. Right now, the Salt Lake is at its lowest level ever. It's dropped 20 feet since the 1980s, which threatens the ecology, the appearance and everything else about this very odd and unique ecological wonder.

Antelope Island, protected by Antelope Island State Park, becomes a peninsula when the Great Salt Lake reaches extremely low water levels. (Photo: Annica Beckman, Pixabay)

BASCOMB: And you've got to think, if there's so much less water in the lake, all of the salt that makes Great Salt Lake must be more concentrated? I should think that that's gotta make it even more difficult for the unique plants and animals that live there to survive.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, there's less water in the lake because of persistent drought, because of some very low levels of winter snowfall. And also, as the agriculture industry grows, they're diverting more water from the freshwater streams that feed the Great Salt Lake.

BASCOMB: Well, let's hope things can turn around. I've also read that Utah is one of the fastest growing states in the country, putting more demand on the water resources that they do have. It's quite a difficult situation.

DYKSTRA: That's a problem throughout the West.

BASCOMB: Indeed. Well, what do you see for us in the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: 1933, one of the greatest probable hoaxes in the history of nature got its start. July 22, 1933, to be precise. Mr. and Mrs. John Mackay were travelling along the shores of Loch Ness hoping to get some fishing in and they said they saw a dinosaur cavorting in Loch Ness, hence the birth of the legend of the Loch Ness Monster. A couple other people came forward and said they'd seen the dinosaur too. There was one very famous kind of shady looking photograph of this long, crooked necked creature reaching up out of the loch. But what's happened since then, is a remarkable tourist industry based on something that scientists tell us doesn't exist: the Loch Ness Monster.

The famous photo of the Loch Ness Monster, claimed to be taken by British surgeon Colonel Robert Wilson on April 19, 1934 and published in London’s Daily Mail. (Photo: Christian Spurling, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: I've read that Loch Ness has a lot of eels. And maybe it could just be a very large eel that people are seeing? Or, or maybe this just makes more sense if you want to keep bringing in that tourist money to have a sighting every few years.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, it kind of helps to have a sighting and keep the tourist trade going, and the T-shirts and everything else. An eel as big as what is purportedly shown in that famous picture, I don't think so. Maybe there was a little bit too much Scotch being consumed. But the Loch Ness Monster, as a legend, just like Bigfoot and Sasquatch, are here to stay.

BASCOMB: Aren't our lives a little richer because of them? Really. It's nice to think, well, maybe there's some things in nature that we don't quite understand.

DYKSTRA: Well, to be sure there are people running tourist concessions whose lives are a little richer thanks to the Loch Ness Monster.

BASCOMB: That's the truth. All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby. Thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Biden’s Fraught Saudi Visit Garners Scathing Criticism and Modest Accords”

- Reuters | “Utah's Great Salt Lake Is Drying Out, Threatening Ecological, Economic Disaster”

- BBC News | “Loch Ness Monster: Is Nessie Just a Tourist Conspiracy?”

[MUSIC: Scottish Music Loch Ness Monster]

Blue Trees Against Deforestation

Blue trees outside the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. (Photo: Jacob Rego)

BASCOMB: Conversations about climate change often focus on the destruction and degradation of the natural world, but artists like Konstantin Dimopoulos are taking a different approach, raising awareness with art. The Blue Trees project is one of his recent pieces of artwork. As the name suggests, he paints tree trunks bright blue, creating a brilliant contrast with the greens, yellows, and oranges of the leaves and natural scenes that surround it. He and his team have worked on installations all over the world, several of which are based in the U.S, including one now in Salem, Massachusetts. For more I’m joined by the artist himself. Konstantin Dimopoulos, welcome to Living on Earth!

DIMOPOULOS: Thank you very much for having me.

BASCOMB: Tell us first please about this art installation. Where have you painted the trees blue and any idea how many you have so far?

DIMOPOULOS: Well, we started in 2003 in Melbourne, Australia. Where I grew up in New Zealand, Wellington, there were very few trees. When we came to Melbourne, it was just amazing. It's one of the largest urban forests in the world. And so that started me looking at trees. And then I went to visit Friends of the Earth. And while I was there, someone had come back from Southeast Asia, and showed us images of this incredible ecocide. And they said, how can we get people in cities to be aware that this is happening, and so I came up with an idea of coloring trees blue. And it's not just coloring trees, we work with children in schools. A lot of trees are donated back into this community, and we've done it in about 30 cities around the world, maybe over 100 sites, and it continues to grow.

BASCOMB: And why make the trees blue? What does that represent to you?

With the exception of the Colorado blue spruce blue trees that naturally typically don’t grow in nature, Konstantin explains. Hence, he chose an electric blue to capture the attention of passersby. (Photo: Konstantin Dimopoulos, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

DIMOPOULOS: How do you get people to stop and slow down, it's the color that will grab attention. You're fighting for attention in the world today. Blue doesn't exist in trees. Now there are red trees, there are a yellow trees, there are green trees. And one of the things I always remember was, in the 1970s, a group of Greenpeace activists went to the Arctic and actually colored seal pups blue, because they'd been being killed for their fur. Part of that was maybe if we put something on a tree, it make people to say what's happening. You know, nature uses color in a variety of ways. It's an incredible powerful attraction, usually it's the male that's all colorful, to get an attraction from someone. Or, like here in Australia, you have a red back spider, and it has a color on it to say, don't come near me, I am dangerous. So, color has always been an important part of the ecosystem.

BASCOMB: And to be clear, the color that you use is nontoxic and it washes off, it's not hurting the trees.

DIMOPOULOS: No, we've had it tested by science. You know, in Greece, when I was young, my father colored olive trees white to protect them from bugs. In Colorado, there were over 100,000 trees a day dead because of the pine beetle. In the Northern Hemisphere, like Norway and Sweden, they also color them white to protect them from the cold. So, it's not a new technique, it's just that the mixture that I've done is very, very intense, electric blue. And this washes off. Virtually all the places that we've created it now has disappeared. It's just no longer.

BASCOMB: So, you've mentioned that you work a lot with schools and children to do this art installation. I understand that you've also worked with people in the homeless community. Can you tell me more about that?

Konstantin Dimopoulos is an environmental and social artist. (Photo: Courtesy of Konstantin Dimopoulos)

DIMOPOULOS: I guess I see myself as a social artist, homeless was affected when we're doing the blue trees in Seattle. And they said whatever you do, just be aware there's a lot of homeless there, don't interact with them. When we got there, they were just lovely. You know, one lovely girl, Clara—she was an artist, and she had artworks there. And my wife Adele would say, Clara, do you mind going to get some coffee for the team. And she'd go and give her the money. She'd never returned any money. But we didn't mind because she was working, you know. And other people said, I'm going to sleep underneath the tree tonight, so nobody hurts it. They were just lovely people. One was a Microsoft executive that lost his job, you know, he came with a suit and everything. And you know, these are people with families that need help. And so, I did work called Purple Rain, using QR codes, we talked to about 12 to 15 homeless who have turned things around. But we talked about their success, how tough it is, you know, some of the domestic violence and stuff that they've gone through is horrific. Although I'd like to think that we as artists are the light of the world, I think we're really the cracks of the world. You know, I love that Leonard Cohen song, when it's a ring, the bells that still can ring forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That's how the light gets in. So, we're not actually the light of the world. But we are the cracks that allows the light to come through.

BASCOMB: What kind of reactions have you had to the blue trees so far?

DIMOPOULOS: In most cases, people are positive. But some people are fighting why you're doing this to our trees. You know, people don't like their environment changed, but we go into other species’ environments and change them massively. And when you remove a tree, you don't just remove a tree. You can't bring back the species that exists within them. And it is good that people get stirred up about what we're doing to the trees, but they need to also look at it globally. Because whatever happens in the Amazon will affect what happens in Boston. And so, when people look at the blue trees and say well, that's insane. I say well, you know a tree would rather be blue than be cut down if that was the choice of the tree.

Purple rain is one of Dimopoulos’s recent projects where one can scan a QR code and get background information about homeless people’s lives. (Photo: Courtesy of Konstantin Dimopoulos)

BASCOMB: How do you think this art installation might inspire change? I mean, what is your hope for this installation? What's your goal here?

DIMOPOULOS: Initially, there was no idea of what was going to happen. But I think what's happening is as we go to different cities, it's almost as though people are drawing a line and saying, our city is going to become more environmentally conscious. It's really, it's important just to get it out, because it's almost as though nobody was caring in some ways. And what the blue tree tries to do is actually just raise the idea.

BASCOMB: What do you see as the role of beauty in this fight against climate change, which can so often seem just ugly and destructive?

DIMOPOULOS: Art for me, there is a beauty about it. Someone looked at the blue trees that we did in Houston and was telling him about the issues about deforestation said yes, but they also looked incredible. And that's the thing is, you're looking at the trees in a different way. And I think art throughout the world has been a way of bringing us closer to beauty. I think that the importance of art is how really beautiful the world is and how we forget about that in some ways.

BASCOMB: Konstantin Dimopoulos is an artist and creator of The Blue Trees installation. Konstantin, thank you so much for your time today.

DIMOPOULOS: No, thank you so much, and good luck with everything.

Related links:

- Konstantin Dimopoulos’s website

- About the Blue Trees

[MUSIC: Dar William’s “After All” from Green World on Razor & Tie records, 2000]

Big Dog, Soft Mouth

South Georgia Island in the Antarctic Ocean (Photo: (C) Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Many animals will give warning signals before they inflict any harm. Think of a dog’s growl, the false charge of an elephant, a rattle snake’s rattle. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, shares this story of an Elephant Seal giving a warning to a nuisance bird.

Big Dog Soft Mouth

Giant Petrel & Elephant Seal

Gold Harbor

South Georgia Island

© 2022 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

At Gold Harbor on South Georgia island, a primal scene unfolds. There, instead of the Pandemonium he expected, Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender found an abiding morality, and restraint.

The full length of the cove out to the vanishing point where the beach meets the wall of the headland and from the water’s edge inshore toward where the grasses grow in tufts, here in this expanse a great herd of elephant seals abides. They snort and roar. Their flippers scoop and fling arcs of sand onto their unprotected backs; it sounds like dry rain, this their sole concession to the omnipresent sun. Incessantly they complain though crowded in upon each other by choice.

While fur seals howl, giant petrels strut and growl. And high on the smooth and rising inland plain a hundred thousand king penguins whistle and wail and the blue glacier hanging over creaks and cracks. It is the loudest place on Earth it is, Pandemonium! There is no peace here. There is no rest here.

Only the carrion lying on the beach is silent. A silent which, in that fatalistic way the Natural World treats such things, the animals ignore. Except for the giant petrels who pay rapt attention.

For the petrels, an unaccustomed feast. Enough for every single one of them. And more. More than the giant petrels could possibly eat in all the long daylight hours that will burn here for weeks to come. And still they fight and cannot give quarter.

An elephant seal and giant petrel gather on the shore of South Georgia Island. (Photo: (C) Mark Seth Lender)

A giant petrel leaps, hunkers, head ratcheting, shoulder-to-shoulder leftright rightleft:

Ruhh – Huhh – Huhh – Huhh - Huhh!

The glare of his eye is blue fire. The mantle of his face a red banner. The terrible hook of his beak precedes him, his webbed feet end in claws that knead and grab and hold his place that none can dislodge him. None dare approach him.

Except for the one who creeps - and bites him! From behind!

And so it begins.

Up the shore and down the shore the two giants battle, on and on, while others feast. Too closely matched; one cannot claim victory nor the other admit defeat. Each is consumed only with his challenger, they have no eyes or ears or taste for anything else. It is, endless.

An elephant seal begins to bark at them. They have crossed and crossed again almost on top of her.

She barks louder; her brow furrows.

They do not ignore her (they do not even see her).

She barks, they fight (you would think they are deaf).

And then, she has had, enough. She grasps the nearest one by his wing with her mouth full of teeth and all the heavy weight she commands. The petrel continues against his adversary. As if he does not feel it. As if he doesn’t even know. She must have held back. Her mouth too soft. Her grip too shallow. For an instant she lets go and again, takes him, this time from the front of the wing where the flesh is tender about the bone and pulls him to the ground.

Now he knows.

He screams. Tries to pull free. Cannot.

And again she lets go...

The only mark on the giant petrel is her spittle where it moistened and ruffled his feathers. He and his adversary resume but take their fight away from her.

Which is what she wanted.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender. For photos, check out the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Click here to read Mark Seth Lender's Field Note

- Special thanks to Destination Wildlife

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Identify Bird Sounds On Your Phone

The call of the Northern Hawk Owl is amongst the many bird sounds the Merlin bird ID app can identify using the software BirdNET. (Photo: Thomas Landgren, Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0)

BASCOMB: These long days of summer are a fine time to get up with the sun and head out for some early morning birding. But if you don’t know a crow from a cardinal, not to worry. There’s an app for that. Bird Note’s Ariana Remmel has more.

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/identify-bird-sounds-your-phone

Please include the entire transcript, from BirdNote® through the very last line of the document. Thanks!

BirdNote®

Identify Bird Sounds on Your Phone

[cell phone recording of Northern Hawk Owl]

On a morning walk with her dog Aari near Denali National Park in Alaska, Denise heard an unfamiliar bird call. She asked the dog for an opinion –

Denise: [on recording] What do you make of that noise?

– but no luck there. She recorded the mysterious screech on her phone. Uploading the sound to BirdNET, an online tool, matched the call to a Northern Hawk Owl, a medium-sized owl that lives in northern boreal forests.

[Northern Hawk Owl, ML 150433141, 0:18-0:20]

BirdNET’s creators, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Chemnitz [KEM-nits] University of Technology in Germany, trained the software on thousands of bird calls and songs. BirdNET uses artificial intelligence to make an educated guess at the bird calls in any recording.

And Cornell’s well-known Merlin Bird ID app now has sound ID, too. It’s as simple as opening the app, choosing “Sound ID,” and hitting record. It can pick out multiple species in the same recording.

[Morning bird chorus, Quiet Planet QP01 0045]

These tools aren’t infallible. Some similar calls can confuse the apps, and they might not detect anything with too much background noise. Currently focused on species in North America and Europe, BirdNET is working on expanding to more regions. But already, it’s amazing to see what these AI tools can do.

[Northern Hawk Owl, ML 150433141, 0:18-0:20]

###

Written by Conor Gearin

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Content Director: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Managing Producer: Conor Gearin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Northern Hawk Owl ML 150433141 recorded by J. Patterson.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2022 BirdNote March 2022 Narrator: Ariana Remmel

ID# sound-29-2022-03-10 sound-29

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/identify-bird-sounds-your-phone

BASCOMB: That’s Bird Note’s Ariana Remmel. For photos and more information about the birding apps, head on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- BirdNote | “Identify Bird Sounds on Your Phone”

- Learn more about the Merlin Bird ID App

[MUSIC: Stravinksy Firebird Finale]

CURWOOD: Coming up – the way-back machine known as the James Webb Space Telescope.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration.

[MUSIC: Yoyo Ma Plays Bach Cello Suite #1, starting at 3:53 in this recording by the BBC]

Spectacular Images From Deep Space

Called “the Cosmic Cliffs”, this image shows a star-forming region in the Carina Nebula. (Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and CTScI)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Science has yet to tell us whether we and other forms of life are alone in the universe.

Life as we know it would require a habitable planet, but it wasn’t until 1995 that science was able to confirm the existence of another planet around a star other than our sun.

It’s called Dimidium, it’s about the size of Jupiter and orbits a star in the Pegasus Constellation.

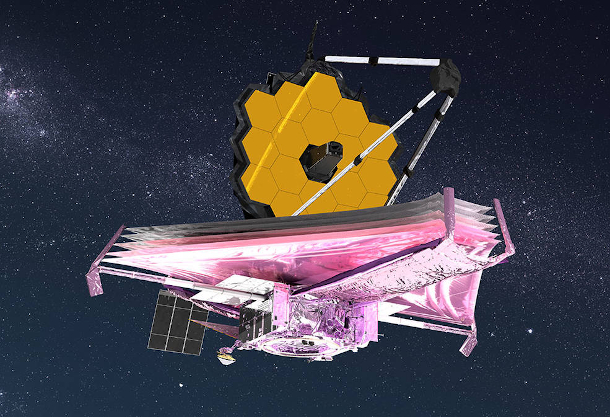

And since then science has found literally thousands more exoplanets, as they are called, and we can expect to find even more with the launch six months ago of the James Webb Space Telescope.

The James Webb is stationed a million miles away where it can look into deep space and thus way back in time.

It can also look nearby at our own solar system with unique eyes that see infrared.

NASA recently released the telescope’s first high resolution images and data, which were gathered as the scope was being commissioned into service.

Here to tell us more is Stefanie Milam.

She’s the Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science at NASA. Stefanie, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MILAM: Thanks for having me again.

CURWOOD: Now, the first photo that we saw that, in fact, the president of the United States was delighted to present was a deep space image. Tell us a bit about it. How far back did it look? And what observations have astronomers been able to make so far?

MILAM: I love this image. The first thing that we got to see from the James Webb Space Telescope was, of course, the SMACS 0723, or what we're calling Webb's First Deep Field. This image conveys 100% of what the James Webb Space Telescope was built and designed to do. So, we wanted to study the first stars and galaxies of the universe. So, this is just after the Big Bang, the infant universe. So, what you're seeing here is, is a galaxy field, and which is absolutely spectacular. There's a lot of peculiar things that you're seeing in the image, like some of the galaxies look like they're streaked or stretched or distorted in some way. And while the galaxies themselves aren't necessarily distorted, the light that they're emitting is actually being distorted, because there's five galaxies sort of right in the middle looks sort of like a belt going across the image, that the mass and combination of these five galaxies is actually pulling and stretching the light of the distant objects behind them and pulling them around. And so that's why they look like you know, Dalí sort of paintings, melting clock galaxies, so they're actually being lensed, in a sense. So, the same way you would imagine any other lensing to happen. So, this is something Einstein told us that was going to happen. And we were able to demonstrate that very beautifully with this image.

CURWOOD: Wait, you're saying that mass can bend light, that something we might sort of think of, generally, as a lot of gravity can bend light?

MILAM: Absolutely. So, we're basically pulling that light from those distant objects around these more massive, closer-by galaxies.

Webb’s first Deep Field is the deepest and sharpest infrared image of the universe ever captured. (Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and CTScI)

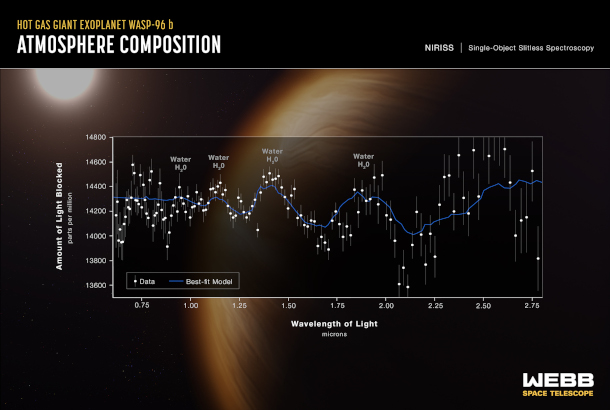

CURWOOD: Now, these early releases from the Webb telescope project, there were five of the four were images, but one was a spectrum analysis of the atmosphere of an exoplanet called dare I say, WASP-96b?

MILAM: Yes.

CURWOOD: Why were the spectrum data chosen to display rather than an image?

MILAM: That's an excellent question. There's a lot of detail that we actually can learn about objects that we don't resolve. Many things across the universe, even in our own solar system are point like objects, so we don't get beautiful pictures of them. But what we do get is with some of our instrumentation we have, so called spectrometers. So, what this is doing is breaking light apart into particular regions across a spectrum. And what we're looking for is the fingerprints of a given atom or a given molecule that's being sort of dispersed across that spectrum. So, say you want to look across the galaxy and understand the different regions with spectrometers. And with the resolution of the James Webb, we can actually take spectrum going across each of those galaxies, so we can study various parts. And so, with the spectrum that was released of this exoplanet, what we're seeing here is evidence of water in the atmosphere of a planet around another star.

CURWOOD: So of course, water suggests the possibility of biological activity. I mean, how excited are the astrobiologists about this?

MILAM: So, this is not necessarily water in the form that we would associate necessary for life. Most life we want something like liquid water. So that's where we come up with this phrase, the habitable zone. So, a planet has to be a certain distance from its star to not vaporize all the water, but also not freeze all the water, so the water has to maintain a certain temperature. And that's where we, we believe that liquid water could actually persist on a, on a planetary surface. And those are the types of objects that we're really interested in understanding in levels of detail that the James Webb Space Telescope is actually going to give us. The spectrum that we saw for the WASP-96b, is of a giant planet. It's a Jupiter sized planet that's extremely close to its star. And what's really cool about this planet, is it's only half the mass of Jupiter. So, it's a really puffy planet. And that whole puffy atmosphere is full of water vapor. So, it's really hot water gas, so not necessarily liquid water on the surface. But it's still a really cool finding. And it's giving us the idea and the first glimpse of the capability that James Webb Space Telescope has for studying planets around other stars. And hopefully getting to that point where we can actually see a planet that has an atmosphere with the kind of ingredients that we have in our own atmosphere. Things like carbon dioxide or methane, even water vapor is a nice telltale sign that something unique is happening on that planet.

This spectrum shows the distinct signature of water vapor, along with evidence for clouds and haze, in the atmosphere of an exoplanet known as WASP-96b. (Photo: NASA, ESA, CSA, and CTScI)

CURWOOD: And, by the way, remind us how many exo-solar planets, how many exoplanets, so far has science identified? And speculate a bit as to what the James Webb Space Telescope might be able to add to that list.

MILAM: So to date, there are over 5,000 known planets around other stars. And that's just because of observational constraints: sensitivity that we have with ground-based telescopes, access to even studying these objects in any kind of detail. We have fantastic surveys up in orbit right now, including things like the TESS Mission, which is actually designed to stare at stars and huge fields across the galaxy, and see whether or not they're twinkling in the right way, suggesting that there's planets going in front of them. So, every time they get a nice suggestion of something like that happening, that's when we do follow up observations and verify whether or not it's a planet itself. So, we are reaching this era of really having a nice list of objects that we want to do some follow up studies, especially with the James Webb Space Telescope, and its capability to study the atmospheric composition of these planets. We're probably not going to be observing all 5,000 of them, and they're discovering more and more every single day. So, what we're hoping to do is get sort of a shorter list of objects that are either in this habitable zone or things that we think are peculiar in general. Maybe it's just a planet that we think is unique, and maybe has some suggestion of a process that's happening within the atmosphere that's something we want to follow up. Earth-like planets are obviously interesting. But there's also all kinds of crazy planets, like look at the diversity that we have in our own solar system.

CURWOOD: You can tell me, I mean, nobody's listening. Have you found Tatooine yet?

MILAM: We have not.

CURWOOD: I mean, this seems even bigger than science fiction, what's going on right now. I mean, people who made the movie series Star Wars, didn't have any of this tech in it.

I made a tool to compare Webb's new images to Hubble! https://t.co/1JqTxabgGC#JamesWebbSpaceTelescope pic.twitter.com/2wRO8t0LXD

— John Christensen (@JohnnyC1423) July 12, 2022

MILAM: Absolutely. This is sort of breaking that realm and blurring now what we have in science versus science fiction. We're in a whole new era of astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science, where now we're able to know that, oh, a planet around another star has clouds and weather the same way that we do on Earth, or that Jupiter has, for example. These are crazy levels of detail, that it's really hard for me to fathom how we can do this so well.

CURWOOD: Now, Stefanie, of all the images and data that has been released to the public so far, what has stood out the most to you?

MILAM: The Carina Nebula. So, we have this fantastic image that was released of what looks like a mountainous gas dust mess with stars sprinkled on top. This nebula in this image, and the spectra, actually, from this image are mind blowing. The amount of information contained in this tiny region of this entire star forming region itself. If you look at the full Carina Nebula images from the Hubble Space Telescope, we're looking at a tiny little edge of one of the bubbles in this image. And the resolution, again, all the detail if you, and I highly encourage everybody to do it, download the full resolution image and start just zooming in. Every time you zoom in, you see something different, something new, a different kind of detail: a color, an enhancement, something fluffy, something rigid, something that looks like a star, something that looks like a galaxy. There is a crazy amount of information in this and already just with our initial inspection. We already have questions in this image that we don't have answers for. And I guarantee the science return that's going to come from something just a simple glimpse in the sky is going to be just rewriting the textbooks

CURWOOD: Rewriting the textbooks, huh? Is there one of these things that you've noticed that you can explain to me what the puzzle is?

An artist’s rendering of the James Webb Space Telescope, with the multilayered sunshield stretched out beneath the observatory’s honeycomb mirror. (Photo: Adriana Manrique Gutierrez, NASA, Public Domain)

MILAM: So, there's a lot of complexity with star formation that we haven't been able to understand or know just because we haven't had the sensitivity and capability to really peer inside these clouds. We are no longer using the Hubble telescope and seeing visible light the way our own eyes see it. We're now pushed over into the infrared region. So now we have night vision goggles when we look at these objects, and we can actually see inside the clouds and the gas and the dust and we can understand what's going on inside of that cloud. That's something we haven't been able to do in a whole lot of detail just because of the sensitivity and capability of other telescopes. So just this first image alone, we're seeing all kinds of new stars being formed. There are new stars actually in the dark region on the top part of this image that have already eaten away all of their nearby gas and dust. And so that's why you have this nice sort of rigid structure at the top of the image that creates this mountainous look. But the new baby stars that are just starting to get formed are within that cloud, within that dust and gas. And when we go to longer wavelengths, using the mid-infrared instrument of the James Webb, they light up. They're like little red flecks of glitter all across that cloud of gas and dust. And those are the brand-new stars that are just starting to form. And understanding that process, how big the stars are, what's constraining the size of how big a star is, when it forms. How much material do they need to actually start forming their planetary systems, which we now know are pretty much ubiquitous across the universe. Almost every time we look at a star, we find a planet now. And we believe that not only do they have one planet, but all of them probably have multiple planets. So, it's just a phenomenon that we're just starting to get insight into. And I think the James Webb Space Telescope is really going to be the tool that really tells us about star formation.

CURWOOD: So, the James Webb Space Telescope has been in operation for about six months at the time we're speaking. How long does it take to process the images that we're seeing? And what does that look like?

Hey @NASASolarSystem, ready for your close-up? As part of Webb’s prep for science, we tested how the telescope tracks solar system objects like Jupiter. Webb worked better than expected, and even caught Jupiter’s moon Europa: https://t.co/zNHc724h9X pic.twitter.com/tW9AT5ah6T

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) July 14, 2022

MILAM: That is an absolutely fantastic question. And this is where I'm getting really, really nervous and anxious as we start getting James Webb Space Telescope science data down. All of these images that you've seen, were all observed and collected within the last few weeks of time. So, we started around mid-June. They're not the only things that we were doing with the telescope at that time, we just kind of squeezed in getting these images, sort of in the background as we were doing the rest of our commissioning activities. These are just blinks of an eye. These are very short periods of time to actually collect these data. Once that data is down on the ground, we have an automated process to put all of that information into something that a scientist can take, analyze very quickly, and interpret and publish. The amount of time that, considering that we just observed these objects a few weeks ago, and we already have them in a high-quality image that has been released to the public, with levels of detail and analysis already revealing new phenomenon, new science, new questions, with just this blink of an eye of the James Webb Space Telescope has been absolutely mind blowing. An exoplanet spectrum that's usually acquired takes months and months for a standard facility to do a full detailed analysis, to calibrate things. And we were able to turn this data around within a matter of weeks. This is an absolutely exceptional facility. And the team that has put together the whole data pipeline from delivering the data from the telescope to having it in your hands has just done tremendous amounts of work to ensure that this is going to be a very rapid process. And it has to be. This is so much information. This is so much data. There's no way we have enough time to ever analyze everything. It's very intimidating, but also extremely exciting.

CURWOOD: Sounds like we need more people in this kind of science.

MILAM: Absolutely. And now we have a 20-year mission. You're seeing two weeks’ worth of data, and all of the amount of information that's contained within these five images. Just imagine how much we're going to have after our first month, after the first year.

Stefanie Milam, outside the cleanroom where the James Webb Space Telescope resided. (Photo: Courtesy of Stefanie Milam)

CURWOOD: Now, in addition to the first five formal science, images and spectra, NASA has also released a couple of images of our nearby planet, I mean, comparatively, Jupiter taken during tests for the telescope. What do those images tell us now?

MILAM: So, I am the planetary scientist that's working on the James Webb Space Telescope project. So, we actually were able to do some commissioning tests on solar system objects. So, there's a number of things that we had to do to make sure that the observatory could actually observe things in our solar system. Planets, comets, asteroids, all these things move with respect to their background stars. And so, we have to make sure this giant floppy telescope that's designed to see the first galaxies of the universe can now fly across the sky and track a comet when it's coming into the inner solar system. But we also have extremely bright objects. We have the brightest thing in the infrared sky in our solar system, and that's Mars. So, we have to make sure we can actually observe these types of objects, including Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. And so, part of our commissioning activity was to make sure that we could do these types of observations. Mostly because they're so big and they're so bright, that light floods the entire instrument field of view. So, all of our science instruments see that light whenever a giant planet is anywhere near it. So, we had to understand how we could actually do observations of things like Europa, or pick your favorite Jupiter satellite, or pick your favorite Saturn satellite, Titan. All of these things have to be observed with the James Webb Space Telescope. So, the images that you saw from Jupiter were actually part of those tests to understand what that light actually looks like. When we saw these images come through, myself and my team, we just sat there in awe for a moment. And you know, of course, it's the solar system object that almost every major NASA observatory has used as their first image release. And here we are, just mind blown all over again. We've imaged Jupiter at near infrared wavelengths and mid infrared wavelengths and optical wavelengths. But every time you look at it with a new instrument, with a new telescope, something is revealed. And the most surprising thing that I saw in these images was that you can actually see Jupiter's rings. That is a very hard thing to do with an optical telescope of any kind. So, James Webb Space Telescope is opening up a whole new realm for planetary science as well.

Stefanie Milam is NASA’s Deputy Project Scientist for Planetary Science for the James Webb Space Telescope. (Photo: Courtesy of Stefanie Milam)

CURWOOD: So Stefanie, what can we expect now these first images have been released? I mean, how often are we going to get to see more photos, as you talked about the many years ahead, but kind of what's next?

MILAM: Well, we've started science, and there's a handful of programs, that data becomes public immediately to sort of have this rolling opportunity of sharing the amount of information, the images, the spectra that we're collecting with this fantastic observatory. Standard observing programs give the scientists that submitted that program, about a year's worth of time to work with the data before it becomes public. So, we didn't want to sort of lock everything up in this year full of secrecy with the scientists, we wanted to have something that we were able to give out to the community, let the public see what we're doing and the amazing capability of this observatory, beyond these initial images. I'm really hoping we move towards something like having an image of the month or something fun like that, just so we can keep everybody informed and engaged. But once the scientists start getting their hands on their data, they'll start publishing in very timely ways. So, stay tuned.

CURWOOD: Stefanie Milam is the deputy project scientist for planetary science for the James Webb Space Telescope. Dr. Milam, thank you so much for joining us today.

MILAM: Thank you so much for having me again, and I hope you have a great one.

Related links:

- Click here for our previous coverage of the JWST

- Read more on the James Webb Space Telescope at the official NASA site

- Stefanie Milam’s biography page

- The James Webb Space Telescope on Twitter

- Stefanie Milam on Twitter

[MUSIC: Alan Silvestri “Ellie’s Dream” from Contact the Motion Picture Soundtrack, on Warner Bros. Records 1997]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Hannah Richter, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio.

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth