August 19, 2022

Air Date: August 19, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

150-Year-Old Mining Law Robs Public Lands Riches

View the page for this story

Extraction of minerals on U.S. public lands is based on a 150-year-old law that doesn’t require royalty payments or adequate protection for the environment and local people. Reporter Jim Robbins talks with Host Bobby Bascomb about the concerns around a proposed lithium mine in Nevada and efforts to reform the antiquated mining law. (07:51)

BirdNote®: Insects Are Essential

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Insects sustain our ecosystems, as a food source and pollinators of 90% of all plants, but their numbers have dropped by half in the last 50 years. However, growing certain plants directly benefits birds and helps insects keep the natural world ticking. BirdNote®'s Mary McCann has the story. (01:59)

Widespread Youth Anxiety About Climate

View the page for this story

A study led by the University of Bath found that three-quarters of young people surveyed believe the future is frightening because of climate change and 65% agreed with the statement that governments are failing young people. Lise Van Susteren is a general and forensic psychiatrist and a co-author of the study and joined Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb to discuss what young people are expressing about their eco-anxiety and how parents can safely talk to their kids about climate. (14:16)

Climate Anxiety Therapy

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Climate change in the form of things like wildfires, floods, and droughts can have devastating effects on mental health. Now there is a growing consensus among therapists that these mounting challenges should be addressed. Julie Grant of The Allegheny Front explores how people in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and beyond are finding creative ways to tackle climate anxiety, often through community action and healing. (06:51)

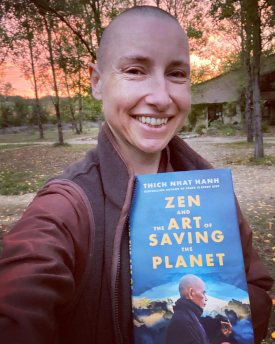

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

View the page for this story

The Zen Buddhist practice of mindfulness can help us break out of a destructive cycle of consumption and live in harmony with the planet, according to the 2021 book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet” by Zen teacher and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh. His student, Sister True Dedication, edited the book and joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to share insights about how mindfulness can provide an antidote to burnout and a source of energy to all who care about climate and environment. (16:04)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Jim Robbins, Lise Van Susteren, Sister True Dedication

REPORTERS: Mary McCann, Julie Grant

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX this is Living on Earth

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

How inaction on climate change is damaging the mental health of today’s

Youth.

VAN SUSTEREN: We found that two thirds of the kids surveyed said

that they were sad, afraid, and anxious. And over half reported a sense

of feeling powerlessness, helplessness, even guilt and shame. Some

children look at what’s happening in the world and they think they

should be doing more.

BASCOMB: Also, a Buddhist prescription for happiness and saving the planet.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: It is our ideas of happiness that have led

us into this current situation. So we think happiness lies in

consuming. But in the essence of our Zen Buddhist teachings, we know

that this beautiful earth, already gives us so

many conditions for happiness.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

150-Year-Old Mining Law Robs Public Lands Riches

Opencast mining (Photo: Geography Britain and Ireland, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University

of Massachusetts, Boston this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.I’m Bobby Bascomb.

To fast-track electric vehicles and a renewable energy transformation we need minerals like lithium that make battery storage possible. But in the US, the legal extraction of those minerals on public lands relies on a 150-year-old law, the General Mining Law of 1872, which doesn’t require that mine operators pay royalties to the government. It was put in place to spur settlement of the West when the country was young but today the antiquated law affords very limited protection for the environment or local people. For more, we turn now to Jim Robbins, a veteran journalist based in Helena, Montana who wrote about the mining law for Inside Climate News. Jim, welcome to Living on Earth.

ROBBINS: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So last year, a new open pit lithium mine was approved and Thacker Pass Nevada, give us a sense, please of the importance of lithium and some of the other minerals found out west in terms of transitioning towards a green economy.

ROBBINS: Lithium is probably the most important mineral for the decarbonization of the world. It is central to electric batteries for electric vehicles. It's lightweight, it holds the charge very well and you can charge it again and again and again. So its importance can't be overestimated. And there is a global competition to be the companies that extract and sell lithium. It's really soared in price in the last few years and will probably go even higher.

BASCOMB: That obviously creates a lot of demand if the price is going up.

ROBBINS: Yes, I mean, the demand is off the charts. And there's a worldwide scramble for new resources. This mine, in Thacker Pass, Nevada, near the Oregon border is the largest in the US. So it's very valuable. It's worth it right now at these prices are over 4 billion. And it may be worth a lot more as the mine continues.

BASCOMB: Now, these mining companies that are extracting these minerals are operating under a law put in place by Ulysses Grant back in 1872. Give us a sense of the law, please. You know, how does it apply to these mining companies and what rights and restrictions are in place?

ROBBINS: Ulysses Grant signed this into law a few months after he signed The National Parks Act that created Yellowstone National Park. So he had a, a varied approach to to the West in just a few months time. The law was created to spur the development of the West to bring people out primarily for gold and silver deposits. It was essentially a giveaway. So people would make the trip to the west and explore. If you go out on the landscape and pound for stakes in and locate a claim that entitles you to explore for minerals on that 20 acres exclusively. And if you find something, you can patent it. And if it's valuable, you have to prove it up, you have to show that it's worth developing. If you do prove that it's worth something you can patent it, which means you can own it outright.

Savage Silver Mining Works, located in Virginia City, Nevada predates the 1872 mining law. (Photo: Timothy O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Well, a lot of the Western US the land is federally owned. This new lithium mine that’s in Nevada, which is almost 90% of the state of Nevada is owned by the federal government, be it Bureau of Land Management National Park, what have you. But you write here that these mining companies that work on this publicly owned land, they don't have to pay any royalties or fees to access the land. I mean, oil companies have to pay royalties, why not mineral companies?

ROBBINS: Well, that's the way the law was written because it wanted to benefit miners who would come out here and make as much money as they could and it would spur development. You know, what's interesting to me is a lot of the mining in the West is done by Canadian companies. So they're profiting off of this archaic law substantially. And then in this case, Lithium America is the largest shareholder is Chinese. And Chinese are one of our great competitors in lithium mining. So a lot of the benefits of the mining law of 1872 are going to other countries and mining companies and other countries. And it seems a bit ironic that our competitors are benefiting from such a law that not only gives away our mineral deposits, but lets them get away with less than a full reclamation of these sites.

BASCOMB: Let's unpack that a little bit. It seems like there's a lot of potential environmental concerns here. And chief among them are water. Roughly 40% of Western watersheds you write in your article have been contaminated by mining. What kind of contamination are we talking about here?

ROBBINS: Well, in this case, it could be sulfuric acid, a story in The New York Times said antimony is one of the minerals that could leach. According to the Environmental Impact Statement, arsenic is another chemical that could leach into groundwater. A lot of times these mines with bare rock when they get rained on, they create sulfuric acid which leeches into the water and this water one of the ranchers has said this groundwater could, could drive him out of business, if it becomes polluted because he won't have any to raise his cattle. It's supposed to drop the water table by 12 feet according to the environmental documents. So there's a whole host of things that the state and federal regulators have said, well, we can live with these. But people are saying well if things get out of control, or they don't happen the way they've planned, then we can have some real damage here.

Large scale mountaintop removal mining operation in the Kentucky Appalachian Mountains. (Photo: Doc Searls, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Right. And you write that the mining companies very often don't stick around to remediate the mines once they're done extracting the lucrative resources or to cleanup the watershed, if they've contaminated. Taxpayers are often left with that bill, how much is that costing us?

ROBBINS: There are 140,000 abandoned mine features across the West. And as of two years ago, it's cost about 50 million for just for one site to clean up and billions of dollars to put these things right. And there is money in legislation pending in Congress that would add to that, because there are so many sites that have been left untreated.

BASCOMB: Let me just get this straight. Because I think this is a lot to wrap your mind around. We have a 150 year old law that allows foreign companies from Canada, China, wherever to come to the United States extract these very, very valuable resources without paying any royalties, any money going to the citizens of this country. The government, they take these valuable resources out, make a bunch of money from it, and they don't necessarily have to pay for the full damage that they might cause. What are we getting out of this?

ROBBINS: Now the company would say, this is critical for clean energy future, the Biden administration has made this a priority to mine lithium and cobalt and nickel and other things central to these batteries. But at the same time, they've said we have to have reform for the mining law of 1872. So we'll see how that goes. There have been bills introduced over and over again, since even before electric vehicles became a thing. I've been covering this subject since 1980s. And there have been many bills introduced to reform the mining law of 1872. They've never passed, there's too much money to be made. And there's a lot of resistance from mining companies which are very powerful. And so any effort to pass congressional reform is probably not going to make it. Experts tell me the best bet for reform will come through regulations. The BLM and Forest Service will have to promulgate those regulations to tighten the law and the reclamation requirements.

BASCOMB: Jim Robbins is a veteran freelance reporter based in Montana. Jim, thanks for your time today.

ROBBINS: You're welcome. Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC: Daniel Estrem, “While My Guitar Weeps” http//:magnatune.com, by George

Harrison]

BirdNote®: Insects Are Essential

A white-eyed Vireo grasps a caterpillar in its beak. (Photo: Kelly Colgan Azar, CC)

BASCOMB: This time of year many of us may be cursing the bugs that bite.

But as BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports, our tormentors are a delight

for birds.

BirdNote®

Insects Are Essential

Written by Bob Sundstrom

This is BirdNote.

[Wood Thrush song in background, followed by Nashville Warbler song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/250158611#_ga=2.263181902.313880498.1…, 0.00-04]

MCCANN:A tiny Nashville Warbler flies to its nest, a fat caterpillar clamped in its beak. Nearly all of North America’s smaller birds, from this warbler to chickadees to thrushes, raise their young on insects—especially insect larvae like this juicy caterpillar.

[Rose-breasted Grosbeak song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/248683961#_ga=2.121617544.1090204237…, 0.30-.34]

MCCANN:Insects sustain our ecosystems, and not just as a food source. They also pollinate 90% of all plants. And without plants at the heart of the food web, life on earth would simply collapse. As naturalist E.O. Wilson put it, insects are “the little things that run the world.”

Though insects are small, easily overlooked, and often vilified, most are beneficial. But their numbers have dropped by half in the last 50 years, so it’s now critical to help foster insects. One concrete way to help is to grow native plants that provide food and shelter for insects like caterpillars.

For example, in the Eastern United States and Midwest, buttonbush supports 18 different species of caterpillars and also provides food for birds in the form of nectar and seeds.

Growing such plants directly benefits birds and helps insects keep the natural world ticking.

Contact a local Master Gardener to help you find what’s best for your area. Begin at BirdNote.org.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Rose-breasted Grosbeak song, https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/248683961#_ga=2.121617544.1090204237…, 0.30-.34]

Senior Producer: John Kessler

Production Manager: Allison Wilson

Producer: Mark Bramhill

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Nashville Warbler ML 250158611 M Medler

Rose-breasted Grosbeak ML 248683961 J McGowan

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2021 BirdNote March 2021 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# garden-13-2021-03-16 garden-13

[primary source is Douglas W. Tallamy, Nature’s Best Hope. Timber Press, 2019]

[quote from E.O. Wilson, “The Little Things That Run the World.” Conservation Biology 1 (4); 344-46]

Resources:

https://www.nwf.org/Garden-for-Wildlife/About/Native-Plants

https://www.audubon.org/PLANTSFORBIRDS

BASCOMB:For photos buzz on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Listen to this story on the BirdNote® website

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: medeski, scholifels, martin and wood, North London, Juice, Indirecto Records,

2014

BASCOMB: Coming up – Climate anxiety among young people is leading to serious

mental health concerns.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

CUTAWAY MUSIC: medeski, scholifels, martin and wood, North London, Juice, Indirecto Records,

2014]

Widespread Youth Anxiety About Climate

According to the global survey titled “Young People’s Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon” 60% of the young participants said that they felt ‘very worried’ or ‘extremely worried’ about the climate crisis. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

A recent global survey found that 75 percent of young respondents are frightened for the future because of climate change. The survey, led by the University of Bath, looked at 10,000 youth, ages of 16 to 25 from 10 countries: the UK, Finland, France, the US, Australia, Portugal, Brazil, India, the Philippines and Nigeria. Lise Van Susteren is an expert on the physical and mental health effects of climate change, and a co-author of the study. She’s also a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington, DC.

VAN SUSTEREN: I have been talking with kids now, for many years about their anxiety and I was the expert witness on the psychological damages to kids in the United States is referred to as the Juliana case, we sued the United States government for inaction on climate. So, all of the things that we found in the survey, you know, if we really use our common sense, we probably could come up with them. But people don't always connect the dots. So the fact that we have it now on paper and can wave it in the air is really important. So here's what we found, we found that two thirds of the kids surveyed said that they were sad, afraid and anxious. And over half reported feeling a sense of powerlessness, helplessness, even guilt and shame. And some people will say, what's the guilt and shame? Well, that's an important aspect, first of all, because some children look at what's happening in the world, and they think they should be doing more. Or they look at what's happening in the world and there's a sense that, are they really valued knowing what's that adults know what is being predicted and they're not taking action. There can even be a sense of shame that they're not valued to the extent that of course, they would ask to be, want to be and deserve to be. So that's a little snapshot of some of the sentiments that we found in the kit.

BASCOMB: Well, that makes sense. I mean, if governments and industry know what they're doing know that this is going to cause an unlivable planet, for this large cohort of people and yet do nothing, it sort of sends the message that you know what you're not important enough for us to care about and to really, you know, address this problem in a meaningful way.

VAN SUSTEREN: Bobby, the easiest way to think about this, and I often give this analogy is think of a family. A community, a region, and nation, a planet is like a family writ large. So think about what would happen in your family if your parents didn't take care of you, if they knew that you were hungry, or that you were walking home in a snowstorm, or you didn't have the proper clothing and things like that. We know what that would do for your self-esteem? Well, the planet is that family writ large. So anything that you can think about that would hurt you about a family letting you down, think about it in terms of what government inaction messages to young people.

What can parents do if their children experience climate anxiety?

— ParentsForFuture Global (@parents4futureG) September 14, 2021

First of all, listen and validate their emotions #WeFeelThisToo

With empathy, compassion and kindness parents can offer support so that the fear does not cloud your children's heart or dominate their actions. pic.twitter.com/VF0vOrYOD4

BASCOMB: And over half of the youth in this study reported a sense of doom that the future is literally doomed. Four in ten even said that they are hesitant to have children of their own as a result. That's really dark thinking for such a young age.

VAN SUSTEREN: It is unthinkable, you know, if a child or people adults don't want to have children, that's certainly a personal choice. But to have that decision forced on you how unnatural. And the reason kids don't want to have, or young people don't want to have or say they don't want to have children is twofold. One is that they first of all, they don't want to potentially bring a child into a world that they feel might be chaotic. Secondly, they count up the carbon emissions. And some of them will say to themselves, that they can't in good conscience add even more of a strain on the limited resources and the capacity of the planet to recover. So the added carbon emissions of having another child gives them pause.

BASCOMB: And I mean, governments should really be listening to that, because it's not good for your economy to have a sudden drop out and the demographics. Look at China, you know?

VAN SUSTEREN: Such an astute remark. Let's be realistic and that is that the benefits that older people seniors have, because of their long years of work, are in part paid for by a younger generation that continues to work, you know, we take care of each other all along the generational divide. And this is a point that's actually really important to me, and that is that there is a real generational injustice here on the part of people who have power who are older, and I've even called a generational aggression. When you know that you're hurting someone and you're doing it anyway, you know whether you like it or not, whether you accept it or not, whether you say so or not and whether you're conscious of it or not, it's still aggression. And I see this aggression in the attitude of some people not all, towards the younger generation that's going to have to deal with us.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I do hear, you know, there's sort of the sentiment of older people saying, well, you're overreacting, you're weak, you know, you don't, I don't know, you don't really understand the world. You know that you're overreacting to these things

VAN SUSTEREN: Oh that snowflake thing?

BASCOMB: There you go.

Tens of thousands of demonstrators marched through central Paris as well as other French towns on October 13, 2018 calling on the French government and the international community to do more to tackle climate change. This is one of many protests. (Photo: Jeanne Menjoulet, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

VAN SUSTEREN: Boy, that really really nails me when I hear the baby boomers talking about this generation that is going to have so much to deal with. And I'm not saying that you can't build resilience. I'm not saying that you don't have a collaborative spirit. I'm not saying any of these things. But the idea that we should trash the place, it's sort of like, you know, it's a reverse sort of situation where parents go out of town and the teenagers trash the house. Well here we are with young people looking, waiting, and expecting a planet that's in good shape or at least as good as their parents got it and we've trashed it. And we have, and we're doing it consciously. Now, it's one thing when we didn't know and lots of people didn't know, we know now, we are being warned. We can see with our own eyes.

BASCOMB: Well what did the participants have to say specifically about government action on climate change?

VAN SUSTEREN: The realization is that while obviously corporations are not exempt, and adults generally are not exempt, the kids realize very, very well, that if you really want rapid social change, they know full well, that it's writing policies that protect them for the future, that will assure that we have responsible attitudes, in a sense in place. And by attitudes I mean corporate, I mean social, I mean other political, because after all, businesses need to have policies that they can follow that tell them these are the rules of the road, when they hear that they will make a changes very quickly. Kids are very savvy, they know full well, that government is the one that can unleash the power.

BASCOMB; Well, what do you see in this report in terms of the views from developed versus developing countries which are represented here by Nigeria, India, the Philippines, and you can make the argument Brazil?

VAN SUSTEREN: One of the things about developing countries versus an established country is that in developing country, first of all, the cross section of people, because we had to find kids that were able to get internet, that's number one, and they also had to be computer savvy, of course. So that limits your ability to get a real cross section, you could make the case that we're really speaking to elites, one could make that case. I don't know if we really dug down if you could make that accusation. And certainly, we're not going to spend a lot of money doing something like that. Because it just is very clear. And that is, kids who do have access to what's going on in the world, are very media savvy. So I think we can conclude that the future leaders of countries that are developing are very aware, and they will be the thought leaders, they will be the ones that are speaking out. And those are the ones that we clearly need to talk to us, you know, primarily given the fact that they will have future power.

BASCOMB: Well, you know, so many young people responded with a very, very high level of anxiety and concern about climate change. How does that affect a growing brain? So many of these people are still growing? I mean, does it connect the synapses in a way that's hardwiring them for future concerns?

VAN SUSTEREN: It so does, there is a psychological priming, so that when you have trauma, especially if kids have had repeated trauma and some of these kids have had repeated trauma, what happens is that you are more prone to trauma in the future. So that's the psychological underpinning. And then there's something else that is even more troubling to me and I sort of suck in air because you can't traumatize a generation and not think on many levels, that this isn't going to have an effect on future generations. So it's not only the traumatized people are more inclined to raise traumatized kids because of their own behavioral choices and their own moods and things like that. It's just inevitable but something that's even more sobering Bobby is that we know that there is something called transgenerational it's epigenetic transfer of stress, which means basically, that when you awaken DNA strip, in one generation to code really for stress, that code gets transmitted to the next generation. So it stays awake into the next generation, it doesn't reset and start over at zero. So what you have is the next generation experiencing the trauma of a previous generation. So just think about it in every single way, when you're traumatized. And, and let's just talk about, let me back it up a little, let me just say, how about stress? You know, I say to your listeners, how well do you do when you're stressed? Do you think well? Can you remember exactly conversations? Certainly, you've been stressed and known that you've gotten sick. So it affects your immune system, it reflects your memory, it reflects your judgment. We all know we don't make great decisions when we're under stress. Well, teenagers, young people all the more and as you suggested, for a growing brain, what happens is that you get this sort of neurologic foundation that serves you for the future and it is being altered when it's at its most plastic, as its most responsive. So that's, that's the danger that we face. And I don't want to say it's only bleak, because we don't want to suggest that kids have only a bleak outlook, and they're victims and all the rest. The world is waking up and we need to talk about that, too.

Participants from the global south expressed a high concern for the climate crisis with 92% from the Philippines describing the future as “frightening”. (Photo: Felton Davis, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah. Well, you are a practicing psychiatrist, what do you think is an appropriate age for parents to start having these types of conversations with their children? You know, I think most parents want their kids to have a carefree childhood, they don't want them worrying about the existential threat of climate change and, you know, causing this harm that we've been talking about. But at the same time, I mean, that's the reality of the world. And we need young people to care about it, you know, we need everyone together, you know, to push for action on this. How do you square that circle?

VAN SUSTEREN: So, so well said. And I get that question a lot. So I have my three L's as listen, learn and leverage. So it is never too early to encourage a child to respect life. And by life, it's all nature, and all animals and plants. They're all our brothers and sisters, we evolved from them, we know how much we share. So teaching kids to respect life, at the earliest of ages is critical, so that you can start before you ever say a word about climate. So what I've also learned is that it is really important to listen to kids. What are your kids saying? A lot of kids have heard stuff. And so you might say to them, you know, there's a lot of talk lately about the weather and if they have older siblings, they might have heard about it, ask them what they have heard. And, you know, sometimes I had a patient who has child thought, heard about extinction and thought that the family dog Charlie was going to die and hadn't said anything to the mom but was harboring this fear that Charlie was going to die. And it's why it's so important to hear about what your kids are thinking. So listen to what your kids are saying. Learn about what you need to know so that you can talk to them. And then you can say, and this is the leverage part, you can say to them, yes, and you are right, there has been a lot of this. Never lie to a kid. What you might do is disabuse them of some of the irrational thoughts that they have. But tell them you understand their fears. And then this is where you go to say, well, that's why in our family, and then talk about what you do to protect nature, or if they're old enough the climate, depending upon their age of course, how you respond is important. So that's why we turn out the lights, that's why we don't take a lot of or any plane trips, that's why we eat the kind of food we do, that's why we have a garden, etc. And if you haven't been doing those things this is the perfect opportunity to make your child feel important and say, you know what, based on what you've just said to me, and what I've heard about what you're thinking, our family is going to do more to make sure that the planet is safe for you. So you can use these conversations not only to steer them in the right direction, but to build their self-esteem and resilience, these are empowering words to a child who feels vulnerable.

BASCOMB: Dr. Lise Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington, DC, an expert on the physical and mental health of climate change. Thank you so much Dr. Van Susteren for this chat and all of these great advice.

VAN SUSTEREN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Watch a panel hosted by AVAAZ on how youth climate anxiety is linked to climate inaction

- Learn more about Dr. Lise Van Susteren’s work in studying the physical and mental health effects of climate change.

- Read the preprint in The Lancet here: "Young People’s Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon"

[MUSIC: William Coulter and Benjamin Verdery, “Song For Our Ancestors,” Song For Our

Ancestors, traditional African/based on Thomas Mapfumo’s mbira arrangement, SolidAirRecords]

Climate Anxiety Therapy

Rebecca Carter, talking with Julie Grant of The Allegheny Front about her concerns with climate change. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie for The Allegheny Front)

BASCOMB: As we’ve been hearing, climate anxiety is a serious concern for mental health, especially in children. So some mental health clinicians are preparing now for the onslaught

of need they see on the horizon. Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front has this story from Pittsburgh.

GRANT: A small group of high school students from around Pittsburgh have set up chairs in a circle on the patio outside of Phipps Conservatory. They're here because they're concerned about climate change, and they each have their own reasons.

BERTOLET: My name is Claire Bertolet. I am a ninth grader at Allderdice High School in Pittsburgh, PA. And I'm afraid that in the future, life is not going to be like it is today. And we're not going to be living as comfortably, and so I feel like in the future, it's going to be too late.

KURTZ: My name is Malcolm Kurtz. I am a junior at Allderdice High School. I'm an avid hiker and birdwatcher, and I'm really concerned with how species are affected by climate change.

Members of Pittsburgh Youth for Climate Action gather at Phipps Conservatory and Botanical Gardens in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on October 4, 2021. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie for The Allegheny Front)

GRANT: These and other students gather monthly to talk and plan ways to work on the issue. I kind of expected to hear they were angry with adults, sad or depressed about the state of the planet. And they did express some of those feelings like Ava DiGiacomo, a sophomore at North Allegheny High School.

DIGACOMO: It's kind of like a helpless feeling, like this summer I started spending a lot more time outside. And there were moments when I would just sit and think this world is so beautiful, and it's slowly getting like ruined, and sometimes it feels like personally, I can't do anything that's really going to make a big change. And that's not an easy feeling to deal with.

GRANT: But these students are creating community around climate action, so they don't have to do it alone. On the evening we met, some had just attended a Climate March and the group had organized a bicycling event called Pedal-Topia. Rebecca Carter is a junior at Pittsburg CAPA.

CARTER: Things like Pedal-Topia where we can get together and do something in nature as a group and as a group of activists can be really helpful and cathartic.

GRANT: Psychiatrist Elizabeth Haase thinks students like this are on the right track. She's Chair of the American Psychiatric Association's climate change committee, and says feelings of eco-anxiety, of grief and longing for what's been lost in the environment, and worry about what will happen with climate change are all becoming more pervasive. She's among a growing group of mental health professionals pushing for more climate awareness among counselors. Haase says treating climate anxiety is not the same as clinical anxiety disorders.

HAASE: It's a different animal, it's a different response, when you're facing a real world problem.

GRANT: Haase compares it with treating someone with claustrophobia. She would encourage that person to face their fear and spend time in enclosed spaces, like a subway car. But that doesn't always make sense.

HAASE: That is not an appropriate response when the subway car is on fire. The subway is on fire. You don't want to sit there and let your fear wash over you, right? You want to start doing stuff.

GRANT: When her patients express concerns about natural disasters, climate change, and ecological collapse, she advises them to find ways to talk with their family and friends about it. And to take action: to join a climate group, write to their local congressperson, or pack up photographs and important belongings in an emergency backpack.

HAASE: Even just doing something like that gives you a greater sense of control, and it creates a safer space for you to be in when something bad is happening.

Walter Lewis, CEO of the Homewood Children’s Village in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania says a few years ago he wouldn’t have connected climate change with the mental health of his organization’s clients. That’s starting to change. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie for The Allegheny Front)

GRANT: Psychiatrist Gary Belkin wants the mental health community to start taking action too, and quickly. He says there's already more mental health needs than there are available therapists, and climate change--the heat, droughts, and wildfires, and the general background stress it causes--is going to make that worse.

BELKIN: We really have to get good at rethinking how we can reach a ton of people across that spectrum. And the only way we're going to do that is by enlisting communities to be part of doing that.

GRANT: Belkin is a former deputy health commissioner of New York City and is now focused on the social aspects of climate change. He spearheaded a program in New York where mental health professionals trained employees at childcare centers, churches and programs for at-risk youth, places that he calls the front lines for mental health.

BELKIN: And we skilled those staff in screening for distress and illness, for basic counseling skills. We have to engineer things so you don't have to look for care or support, you trip over it.

GRANT: One group on the frontlines in Pittsburgh is starting to look into climate change and mental health: The Homewood Children's Village. President Walter Lewis says they have advocates who stay in touch with their 300 members. They focus on education, economics, food, and health, including mental health.

LEWIS: Probably three, four years ago for sure, it would have never dawned on me to think about some of the types of trauma, mental health impacts, of climate change.

GRANT: Disadvantaged communities like Homewood are expected to experience worse climate impacts than their wealthier neighbors. So even though his advocates are not mental health professionals, Lewis says he can still raise their awareness that a flood in the basement or some other climate-related event can be traumatic for clients.

LEWIS: Hey, you know, we just had a heatwave, you know, these are some things you might want to think about when you're talking to you know, your families or the children that you work with.

GRANT: As the number of people reporting anxiety and stress around climate change grows, others in Pittsburgh are trying to expand the available mental health care.

EVANS: Hello, everyone! My name is Gloria Evans, and I am one of the certified facilitators for integrated community therapy. We want to welcome you tonight.

GRANT: This integrated community therapy facilitator is using a technique developed and practiced in Brazil for 27 years, to bring groups of people together to share their experiences, learn from each other, and gradually deal with problems in their families and neighborhoods.

THOMPSON: The goals of this method are to help people learn how to express themselves, sort of have emotional literacy, to how to talk about their feelings.

GRANT: Ken Thompson is a community psychiatrist based at the Squirrel Hill Health Center in Pittsburgh.

THOMPSON: Also how to help people develop a sense of empathy with each other.

GRANT: Facilitators are trained over months, not years. There are now around 40,000 facilitators in Brazil. Thompson's group is starting to train facilitators here. And as the climate changes, he says, people are going to need safe spaces like this where they can talk and connect with others.

THOMPSON: When you share that, it becomes a real powerful glue. And I feel like we need glue. We need a lot of glue in this society, you know, at least to keep us hanging together.

GRANT: In our polarized society, efforts like this are starting to help more people relearn how to talk with others and see their shared humanity and hopefully re-weave some of the community fabric that's been pulled apart. Because as climate change worsens, people are going to need each other.

BASCOMB: That story from Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- The Allegheny Front | “How to address the looming crisis of climate anxiety”

- About Pittsburgh Youth for Climate Action (PYCA) from Communitopia

- American Psychiatry Association | “Climate Change and Mental Health Connections”

- Climate Aware Therapist Directory

- Homewood Children’s Village

- Visible Hands Collaborative

[MUSIC: Agnes Obel, “Myopia,” on Myopia, by Agnes Obel, Deutsche Grammophon]

BASCOMB: Join Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood and ProPublica on August 24th at 3 p.m Eastern for a live conversation about the climate debt crisis. Few regions are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than the Caribbean, with its multiple climate hazards.These islands also carry a lot of national debt.ProPublica reporter Abrahm Lustgarten went to Barbados to investigate and found that rising sovereign debt is now a hidden but decisive element of

the climate crisis. Register today for this free, online event at loe.org/events. That’s

loe.org/events.

[MUSIC: Agnes Obel, “Myopia,” on Myopia, by Agnes Obel, Deutsche Grammophon]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

MUSIC: UglyBurger0, “Friday Theme” on Roblox 3008, Vol.1 (Original Soundtrack), uglyburger0]

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet is one of over 130 books written by Thich Nhat Hanh. (Image: courtesy of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Zen Buddhism encourages mindfulness and meditation as ways to embrace life and its challenges, including one of the thorniest challenges of all, the climate crisis. In the 2021 book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, Buddhist Zen master and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh says being in the present moment, waking up to our suffering, and acting with compassion can ripple out beyond ourselves and lead to better care of this planet we call home. Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet was edited by Sister True Dedication, a monastic Dharma teacher and Buddhist nun who lives in the Plum Village community Thich Nhat Hanh founded in France. She and his other students call him “Thay” which is Vietnamese for “Teacher”. I recently talked with Sister True Dedication and she began by explaining how we got into our current pattern of exploiting the earth.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: It is our ideas of happiness that have led us into this current situation. So we think happiness lies in consuming. We think happiness lives in striving and competing and satisfying our craving in whatever way and having these extremely resource rich experiences. But in the essence of our Zen Buddhist teachings, we know that this beautiful earth, this extraordinary planet, already gives us so many conditions for happiness. And so there's a radical kind of message in our approach to simplicity. Which is, if we give ourselves a chance to cultivate true presence, to generate what we would call an energy of mindfulness, we realize that we don't need all those things to be happy. We don't need a second car, we don't need a bigger house, we don't need more vacations. We just need to change the way we look and experience things and discover the happiness that is already there for us. And on a planetary scale this is one of the core insights that as a species, humanity, we would need to wake up to, in order to be able to change our way of living. Because our current economy, our current lifestyles, are leading, and we know this very clearly, our lifestyles are leading to the destruction of our beautiful planet, of the natural world. And there's nothing to be afraid of in this kind of simplicity, that takes us in another direction away from the mindless consuming.

Members of the Plum Village monastic community in France, where Sister True Dedication lives, plant trees in late 2021. The Plum Village brothers and sisters strive to practice the art of living in harmony with one another and with the Earth. (Photo: Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism)

DOERING: So this book, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, is really calling for a radical shift in the way that we understand ourselves in relation to everything else. You call this an "insight of interbeing." Could you explain this and tell us why is it important to our efforts to address climate change and other environmental crises?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So the word "interbeing" is a word that our teacher created, it's not a word that you can actually find in the dictionary yet. And it really means that we can understand that we inter-are, we are profoundly interconnected with everyone and everything around us, including the living world, including the natural world. What this means in the light of our planet is that, in fact, some of the reasons and the ways of thinking and seeing that got us into our current problem, are because we see the Earth as something outside of us, something separate, even something inert that is there for us to exploit, to be master of, that is there somehow for us to use. But with the insight of interbeing in the Buddhist teaching, we see that we are part of the Earth, we are profoundly interconnected with the Earth. And this is fully in line with science and the teachings on evolution. For example, a tree is not just there to provide us with fruit. It is not just there to provide us with wood to make furniture or build our homes. Like, our trees are intimately part of who we have become as a human species. Their oxygen is our in-breath, their out-breath is our in-breath. And to see the life in the tree, the wisdom in the tree, and to not think that we are entirely separate from one another. And we know that there's going to be a radical difference to the planet, if all the trees weren't here, just as there would be a radical difference if all the humans weren't here! So it's to really look deeply using both the eyes of science, but also, like, the eyes of what we might call a more spiritual dimension.

DOERING: You know, one of the key ideas here in the book is about the importance of maintaining ourselves and caring for our own selves, not succumbing to burnout, which I think is something that a lot of people can relate to now in our modern world. Could you tell me about how this, you know, mindfulness and interbeing can really help with that, can really set us up for actually doing the work that we want to do and caring for the Earth in a way that we aspire to?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Hmm. That's an excellent question. Yeah, I think if we want to care for our environment, we have to care for the environmentalist as well. It's like, the two are deeply interconnected. The energy of mindfulness helps us be present in our day, so that we're not kind of lost and swept away and overwhelmed. And that's when we start going beyond our limits, when we get caught up in things and we're not really being, being able to be fully present for what is going on. And so we'd say that in the practice of mindfulness, we learn to be able to handle our strong emotions, our painful feelings, and we also learn to kind of maximize, or optimize, our feelings of well being and happiness. So we're doing these two things at the same time: nourishing joy and happiness, and handling pain and suffering, if you like. In a really granular way, what this means is that when we hear bad news relating to the planet -- we may have watched something on the screen, we may have heard a news bulletin, and a feeling comes up. And that feeling may be sadness, it may be grief and despair. Or it may be anger and resentment, perhaps, especially at our political leadership at this point. So those are real feelings. And in the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, we speak about the power of aspiration and intention. And it's possible to metabolize some of our painful feelings with mindfulness, with concentration and insight, and transform them into a source of energy to take action, and to take radical action, which is what is needed right now.

WATCH: Sister True Dedication’s TED talk, “3 questions to build resilience – and change the world”

DOERING: You mentioned anger, and these emotions that come up with the climate crisis. And it's true, I mean, just a few people and companies have emitted far more greenhouse gases than most of the people in the world. And they've known, largely, the problems with what they're doing. And yet, they're also not the ones that are the most vulnerable to climate impacts. So this is just a huge injustice. And it makes a lot of climate activists very angry. So to what extent can anger like that be constructive? Or what do Zen teachings have to say about, like, how to use it, how to "metabolize" it, like you said?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So Thay, our teacher, once said that a little bit of indignation can be okay, can be healthy enough to get us off the cushion, to engage us into action. But, he said, the energy of anger burns us up, it really burns us up. And for me, we had a very powerful experience in Scotland with some events around COP26. There was a protest at this event against a new oil speculation, oil searching in the North Sea. And there was a very angry young activist and the CEO of Shell had to listen to her directly. And at the time, everyone thought it was terrible and dramatic. But the monks and nuns, those of us there, we thought this was a very healthy conversation. One side had to listen to the other side, and how powerful that this Shell CEO had a chance to hear the voice of the youth and their desperation and their suffering. And anger is there for a reason, anger is there because people are not being heard. So for me, it was very powerful to witness this protest. And the incredible news is that, you know, six weeks later, Shell pulled out of that exact oil field, the Cambo oil field in the North Sea. And for me, my response wasn't a sense of... my response was gratitude to him, and that he woke up and he realized, and was able to oversee that decision to pull out of that oilfield. And we should all be feeling shock and outrage in many ways. But the energy which then gets us onto our streets, or takes us to the voting booth, that energy, if it's an energy of love and positive action, that will sustain us so much more than the energy of anger.

Plum Village brothers and sisters pick end-of-season apples at a nearby orchard (Photo: Plum Village Community of Engaged Buddhism)

DOERING: Yeah, and you, and you mentioned being grateful to the Shell CEO. And it seems like he must have been listening to that activist who was very angry. And like you said, it's a conversation, it's a dialogue. If two sides can come together and respectfully engage, there should be a positive outcome.

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Yeah, in Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, we also explore this question of dialogue, and brave dialogue. When we can meet, human to human, across all the kinds of polarization that we have in our societies, I believe that real transformation is possible. It's when we demonize each other and we demonize our actions that we really are going down the kind of wrong path as a species, because we will need to collaborate, we do need to listen to one another. We do need to find collective insight to get ourselves through this fiendishly difficult problem of really addressing climate change and the destruction of nature in all these aspects. And so what was powerful in the dialogue in Scotland was it didn't necessarily look like the CEO was listening at that time. Because sometimes, listening takes longer for the insight to settle and for courage to manifest, the courage of right action. To offer that gift of listening is I think one of the greatest gifts we can offer one another and that the practice of mindfulness allows us to give. And I think that has huge potential in the climate movement in general. And that's what we've seen in the conferences where we've participated and brought the practices from the book into these conferences. It's the listening that people are most eager to learn.

Zen Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh passed away on January 22, 2022 at the age of 95 after this interview was broadcast. (Photo: Courtesy of Plum Village Unified Buddhist Church)

DOERING: Mmm. And, in fact, I was really interested to read in this book that Christiana Figueres, the architect of the Paris Climate Agreement, is a student of Thay. So how did his teachings help shape the success of Paris?

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: So Christiana has shared with us that it was her own kind of spiritual strength that she drew from Thay's teachings and from various mindfulness practices that gave her the sort of personal strength and faith to be able to carry through all the negotiations leading up to the agreement. But specifically, Christiana highlighted the practice of deep listening. And she found a way through her own embodiment of this practice to be able to show up, and she speaks about meeting both coal investors and island nations that are really in danger. And being able to come with a truly open heart and to ask truly open questions, and to have that sense of inner courage and openness for whatever they wanted to say. To really allow people to find their own words to describe their suffering, their struggle as a nation or as a corporate CEO. It's not that corporate CEOs are without their struggles too, and how can they name and articulate them, and that's their struggles that are driving their unmindful action, right? It's the irony, this is this weird irony in Buddhist teachings, it's exactly by getting in touch with our suffering that we can find the way out of it. It's exactly by waking up to the suffering, naming it, really getting down to what it is, what is driving those oil companies to be so stubborn, about continuing to do what they do, what is it? And in those human beings at the top of those companies, what is it that they are still caught in, that they haven't yet discovered? And only when we can identify and really name it, and be with them, as they realize this about themselves, then right away, we will wake up to the way out and to new solutions. So it's by leaning into these dark places that we can really see the light to kind of find the way out.

DOERING: So for someone who's listening, who is yearning to get in touch with this sense of interbeing, and wants that connection, wants to be able to sort of fuel their care for the planet with mindfulness, and reconnect. What would you recommend in terms of going outside and connecting with nature? And what should the mindset be of someone who wants to do that? Is there a specific question or thought that they should bring to mind or just simply go out and be? What would you recommend?

Sister True Dedication provides commentary throughout the book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet.” (Photo: Plum Village)

SISTER TRUE DEDICATION: Hmm. So the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet opens with a beautiful invitation to listen to the Earth. And a very simple way to know whether we're in the present moment or not, is whether we're with our five senses. So with what we can hear: if you can hear the birdsong, you're in the present moment. With what we can smell: if you can smell the leaves on the forest floor, you're in the present moment. If you can feel the breeze on your face, you're in the present moment, or taste the salt on your tongues, if you're by the sea. So, being with our senses, we're in the present moment already. And to take a moment to really pause. And I think some people say, Oh, my mind's so distracted, my mind is thinking of this, it's thinking of that; my phone's vibrating in my pocket. So maybe you really need to turn off all your notifications before you go on such a walk! And the trick with mindfulness is, the more we allow our senses to be fascinated by the present moment, everything we can see, hear, smell, or even taste or touch -- the bark of a tree, perhaps -- the more we're in touch with these senses, we've got no time to think. You're, the thinking won't happen. So then just keep coming back to all of these sense impressions as we are being with nature, and just really having a moment to be with the vitality of life. So the, the challenge is to open up our curiosity, and that is already a huge source of nourishment, and that is already, we're, we're living the truth of our interbeing with the Earth. It's not an idea. It's not a notion. It's an experience that each one of us can then have.

DOERING: Sister True Dedication is editor of the book Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet by Thich Nhat Hanh.

BASCOMB: Sister True Dedication is editor of the book Zen and the Art of Saving

the Planet. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering. The book was written by Buddhist monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh who passed away at the age of 95 in January of this year.

Related links:

- Find the book “Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn about the Plum Village community founded by Thich Nhat Hanh

- About Sister True Dedication

- NowThis News | WATCH: “Young Activist Confronts Shell CEO About Climate Record”

- The Guardian | “Shell Pulls Out of the Cambo Oilfield Project”

[MUSIC: Benedetti & Svoboda, “Sueno” on Journey to the Heart III: Music for Healing, by Benedetti &

Svoboda, Coroco Sounds]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen,

Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth

Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake

Rego, Hannah Richter and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and

Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on

Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at

livingonearthradio.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer

I’m Bobby Bascomb

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth