September 9, 2022

Air Date: September 9, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Extreme Weather Events and Climate Science

View the page for this story

Scientists have understood for decades how global warming would increase moisture in the atmosphere promoting climate disruption and extremes such as the floods, wildfires, and record-breaking heat waves that 2022 has brought to many regions. But there may be more impacts to come as climate models haven’t captured all the complex interactions of a warming world. Michael Mann, Professor of Atmospheric Science at the University of Pennsylvania, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss. (13:37)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood mark the end of coal-fired power in the 50th state (Hawaii) and discuss how 3D printed homes made from recycled bottles could ease both the affordable housing and the plastics recycling crises. In the history calendar, they look back to 1916 when the world’s first self-service grocery store opened and dramatically changed the way we shop. (05:12)

Renters and Climate Change

View the page for this story

As climate change brings higher temperatures and extreme weather to American cities, our rental and affordable housing stock remains largely under-equipped to deal with these new challenges. Todd Nedwick of the National Housing Trust joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss what renters and landlords can do to fortify homes against a changing climate while transitioning to cleaner energy. (09:57)

Note on Emerging Science: Tigers on the Rebound

/ Hannah RichterView the page for this story

It’s the Year of the Tiger, and for the first time in a century, wild tiger populations have risen, following two decades of conservation efforts. Living on Earth’s Hannah Richter reports on the international strategies that have boosted numbers of this beloved big cat. (02:30)

Green Voters and the 2022 Midterms

View the page for this story

Polls of environment-first registered voters showed that in July, as many as a third were planning to sit out the 2022 midterm elections, with most citing frustration with the lack of Congressional action on climate. Now the passage of the landmark climate legislation in the Inflation Reduction Act may be stirring up some voter turnout among climate conscious voters. Host Steve Curwood is joined by Nathaniel Stinnett, founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, to discuss. (15:07)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220909 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Todd Nedwick, Michael Mann, Nathaniel Stinnett

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Hannah Richter

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Passage of the big climate bill may spur more green voters to turn up for the midterm elections.

STINNETT: Now a lot of them are really, really excited. Not because they have an in-depth understanding of what the Inflation Reduction Act means and what more we need, they don't. But, because for the first time in a while, the wind is in their sails, and that means a lot, and that gets people excited to vote.

CURWOOD: Also, world wide extreme weather events highlight the need for climate action

MANN: We've gotta prevent whatever warming we can and that requires more aggressive climate policy, that requires people voting in these midterm elections for climate champions and voting out those who have acted as apologists for the fossil fuel industry so we can meet that 50% target that we really need to meet.

CURWOOD That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Extreme Weather Events and Climate Science

Years of insufficient rainfall across the Horn of Africa have caused the worst drought in 40 years. In the picture above two boys walk to their settlements in Hadhwe sub-district, which has been particularly hard hit by the drought. (Photo: Mulugeta Ayene, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Extreme weather, it seems, is now almost the norm, despite the horrendous toll it’s taking on humans and countless other species. Science started warning us decades ago that global warming would increase atmospheric moisture and lead to climate disruption, and now we are living with the predictions of those climate models. For some insights into extreme weather and what the models did and did not predict we turn now to Michael Mann, a professor of Atmospheric Science at the University of Pennsylvania, and he joins us now from Philadelphia. Welcome back to Living on Earth Michael!

MANN: Thanks, Steve, always great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, in these last few weeks, we've seen just crazy intense weather, a third of Pakistan flooded now, after they had record heat earlier this summer, cities all over the United States and places from Death Valley to St. Louis, to Dallas and most recently, we're looking at the problem in Jackson, Mississippi, where flooding has taken out the water system. What’s going on? What's happening in terms of climate disruption?

MANN: Yeah, well, you know, it's not rocket science, you warm up the planet, as we're doing with carbon pollution, you're going to get more of these extreme heat waves, more frequent heat waves, so that's a no brainer. You also warm up the atmosphere, so it holds more moisture. So when it does rain, you get more rainfall, you get more precipitation, you get more of those flooding events. And the the heat dries out the soils in the summer so you get worst drought, more widespread drought. You combine the heat and the drought, you get the sorts of catastrophic wildfires that we're seeing out in the western US that we're seeing in Europe that we've seen down in Australia. So that part is all pretty straightforward, it's all basic physics. But there's something else on top of that, which is a little more subtle, and which isn't all that well captured in the climate models. It's the way that the pattern of warming is changing the behavior of the Jet stream, its causing it to get stuck in more of a wiggly pattern, where you get those big high and low pressure systems associated alternatively with extreme heat, drought and wildfire or extreme flooding, and they remain sort of locked in place. So you get those extreme heat conditions day after day in the same location or rainfall day after day in the same location. That's when you see the most profound extreme weather impacts when you get these very persistent extreme weather events. And climate change appears to be leading to an increase in those persistent weather extremes in a way that isn't well captured by the climate models. If anything, we've under predicted that the impact of climate change on these extreme weather events that we're seeing. And what's happened is those events have now, the signal has now risen above the noise. We're noticing the impacts were feeling the consequences. Because the signal the impact of climate change on the frequency and intensity of these events, has now risen above the noise of natural variability. It's plain to see. And we can see it now playing out in real time.

The Mosquito Fire ran 6.8k+ acres yesterday and continues to chunk away. A hydro dam, high tension power lines, water pump stations, and homes are at risk. A massive resource order went in and many out of region resources are responding. #MosquitoFire #wildfire #california #tahoe pic.twitter.com/YhDnj59J0F

— TheHotshotWakeUp: Podcast (@HotshotWake) September 8, 2022

CURWOOD: So this is not a fair question but what else do you think that climate modeling has not captured all that well, that could be in our in our future? In an uncomfortable way?

MANN: Yeah. So these extreme weather events are one example of where the physics is pretty subtle. The physics behind the Jet stream behavior that I was talking about is subtle enough that it's not well captured in the climate models. So it comes down to some of the physics that isn't really represented well enough in the models. That there's other physics that isn't, or at least traditionally hasn't been well represented related, for example, to ice physics and the behavior of ice sheets. And one of the other things that we've seen is that the ice sheets are losing ice faster, earlier than we expected earlier than the models predicted. And we can see why there are processes that we're seeing play out, again, in nature, that haven't been well represented in the models, for example, the cracks that formed the fissures that form in the ice sheets that allow the melting surface water to penetrate to the bottom of the ice sheet and lubricate the base, which allows it to slide out to the ocean more quickly. Or the destabilization of ice shelves, like we see off the West and Antarctic coast. These ice shelves help prop up the inland ice. Now when the ice shelf collapses or melts, it doesn't contribute to sea level rise, because it's already floating on the water. It's like an ice cube in a glass of water. But when those ice shelves do collapse, that removes the buttressing effect that holds back the inland ice and that inland ice can start to surge up to sea. And so we're seeing these processes lead to earlier loss of ice from the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheet and that means the sea level rise from ice melt is happening earlier than we expected. So it's another example of how uncertainty isn't our friend. Look, the climate models have been really good about predicting the overall warming of the planet. More than a half century ago, the predictions that were made of how much warming we would see if we continue to burn fossil fuels at historic rates have come to pass. The predicted warming is what we've actually seen. What's been under predicted are some of the consequences of that warming.

CURWOOD: Among the sort of unusual weather things this year has been the lateness of the hurricane season. What if anything, do you think might be going on there? Is it just a random thing, because you know, occasionally these things happen or might we be looking at perhaps some sort of a trend change here?

Pakistan experienced the worst floods in a century affecting more than 33 million people and causing more than 1,343 deaths. (Photo: Ali Hyder Junejo, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MANN: Yeah, no, I would say stay tuned. I think we would be wrong to dismiss this season at this point. We haven't reached the peak of the season, we’re close to it. But we haven't reached the seasonal peak. And one thing we know about La Niña years, this is a La Niña year. The tropical Pacific is cooler than usual, that affects weather patterns around the world. And it actually often leads to more active hurricane seasons in the Atlantic, but late in the season. When it kicks in is the fall. So stay tuned. I think when all is said and done, we will look back at this season as having been an average season, not a record inactive season, but a relatively at least by historical standards, an average season. And here's the thing, we've gotten used to this sort of increase, which is connected to climate change in hurricane behavior in the Atlantic, that what in the end, I think will simply be an average season historically feels like an incredibly inactive season. So stay tuned, you know, I think we're going to see a ramp up in activity in the weeks ahead.

CURWOOD: So recently, we saw the inflation Reduction Act get passed with on the order of 370 billion, maybe as much as 400 billion dollars to be devoted to dealing with climate, both in terms of reducing emissions and also adapting to the trouble that climate disruption is giving us. I wonder to what extent do you think that finally happened, because we've seen such horrible events over the last few years? I mean, the wildfires are like routine news now in the western part of the United States, amazing flooding. This summer's heat waves are really extra intense in the northern hemisphere but we've been in this situation for a while. To what extent do you think that as a society as a population, we've passed a tipping point on climate?

We visited one village to look at the impacts of #climate change on food security. Short clip below, and the rest ???? https://t.co/Hww7O57k7t 14/15 pic.twitter.com/DARFlxqIza

— Aaron Fernandes (@az_journalist) September 3, 2022

MANN: Yeah, you know, I think that obviously, the Biden administration was supportive of climate action contrasting with the previous administration, with the Trump administration, and was, you know, using the bully pulpit really to encourage and to push Congress into passing climate legislation. But it came down in the end to whether one or two Democrats would be willing to support some sort of climate legislation, and Joe Manchin, a coal state Democrat who had in general had opposed any aggressive climate action has been friendly to the fossil fuel industry, was sort of the gatekeeper in what legislation could pass this 50-50 Senate. And I actually do think that the fact that his own people back in West Virginia are feeling the extreme consequences, the flooding events that they've seen in that state devastating floods, in recent years. I think he was feeling the pressure of all of this climate disruption that was playing out in real time as this bill was being discussed and considered. And I think in the end, it did play a role. And that's really critical, because now Joe Biden can go to COP 27, the next international climate conference and say- look, the United States is meeting or at least coming really close, we need to do more and we need to arguably elect an even larger majority in Congress to pass more aggressive climate legislation. But the inflation Reduction Act comes really close about 40% reductions in carbon emissions by 2030, what we really need is 50%. But it puts us in the ballgame. And Joe Biden can say- look, we're now acting, we're making meaningful progress here in the United States, I think that will lead other countries like China and India, to make more aggressive commitments to ratchet up their own commitments as well. And so the most important impact of the inflation Reduction Act might be its impact on international climate policy and the stature that it now gives Joe Biden were the US the world's largest historical polluter, we now can say the rest of the world we're trying to do our part, please do your part as well.

CURWOOD: We have to take on the responsibility for their loss and damage it sounds like.

MANN: Absolutely, you know, some of this should be thought of as reparations. We reaped the economic you know, rewards of two centuries of dirty energy burning of fossil fuel energy, we grew our economy, but at the expense of the quality of life for the rest of the world. So there is an obligation on our part to help those who have suffered some of the worst consequences and yet played the least, you know, the least role in creating the problem in the first place.

CURWOOD: So, Michael, you study this of course so much of your career. It seems that when we look at these extreme weather events and the impact of climate disruption, that if one is poor or brown, or in the Global South, that it's it's much worse. And yet, of course, the less affluent part of the world did not create these emissions as you point out. To what extent is there still a gap in US policy to helping the rest of the world deal with the ravages of climate? I mean, look, a third of Pakistan is underwater, it's a pretty poor place.

MANN: Yeah, you know, it is really ultimately, it's an issue of ethics, right? We often frame climate change as a problem of science or policy or politics but it's a problem of ethics. Intergenerational ethics, the notion that we could leave behind a degraded planet for our children and grandchildren, but also the ethics of inequality, inequity, wealth disparity, the fact that the Global South, that low income communities, frontline communities are feeling some of the worst consequences of climate change, and yet have the least resources to deal with those consequences. And that, you know, catastrophic flooding in Jackson, Mississippi really captures that quandary, I think, quite profoundly. It's a travesty that hundreds of thousands of people are either without drinking water or drinking polluted water because of neglect. You know, because frankly, the Republican politicians in that state really have provided no commitment, no infrastructure to help the people there deal with these sorts of natural disasters. And this isn't a natural disaster anymore, it's an unnatural disaster. It's been made worse by human caused warming. So, you know, what it really shows us is that we need to provide resources to those frontline communities to low income communities to help them deal with the the impacts that can't be avoided. We've got to prevent whatever warming we can and that requires more aggressive climate policy that requires people voting in these midterm elections coming out to vote for climate, you know, champions and voting out those who have acted as apologists for the fossil fuel industry. So we can get even more aggressive climate action and meet that 50% target that we really need to meet. That's important but at the same time, we've got to provide resources to people to cope with those impacts that are now unavoidable, that are now baked in. And in particular, that applies to those frontline communities, those low income communities. And it's not just the United States, we need to make sure that the US and the you know, industrial world provides support in the form of loans and outright grants of money to developing countries to help them cope with the devastating consequences they're already feeling. And to help them leapfrog past the fossil fuel stage. Make sure that they don't make the same mistake that we made.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a senior scientist, senior atmospheric scientist at the University of Pennsylvania. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thanks, Steve. Always great to be with you.

Related links:

- Michael Mann at the University of Pennsylvania

- The Third Pole | “Floods After Drought Devastate Sindh’s Agriculture”

- The Conversation | “America’s Summer of Floods: What Cities Can Learn from Today’s Climate Crises to Prepare for Tomorrow’s”

- The Washington Post | “Living in A City with No Water: ‘This Is Unbearable’”

[MUSIC: Chet Baker, “Don’t Explain” on Baker’s Holiday, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Coming up – we’ll have some tips for residential renters on how to reduce their household carbon emissions. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chet Baker, “Don’t Explain” on Baker’s Holiday, The Verve Music Group]

Beyond the Headlines

The AES Corporation power plant, shown above, was Hawaii’s last operating coal-fired power plant before it shut down on September 1, 2022. (Photo: Tony Webster, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

And it's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he's on the line out from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, how you been doing during this summer break?

DYKSTRA: Summer break was good, but now back to work, Steve, and that work is a dream trip to the 50th state, Hawaii. It's also the tenth state to go coal free, meaning Hawaii's one and only coal-burning power plant is no more. It had provided about a fifth of the juice on Oahu, the most populous of the Hawaiian Islands.

CURWOOD: So it's aloha, goodbye to coal and coal ash.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but in the short run, it's not ideal, because in order to replace the coal power, they're going to have to rely on burning oil. But since both coal and oil would have to be shipped to the mid pacific, it's an ideal spot for homegrown clean energy.

CURWOOD: So maybe the Hawaiians are going to put up a little more solar or take advantage of the wind or even think about some tidal power, huh?

DYKSTRA: There's talk about doing that, including from the main utility, the one that just shut down the coal plant. And since Hawaiians would be vulnerable to so many of the effects of climate change -- coral bleaching, more intense storms, sea level rise -- there's got to be a little bit extra motivation in the 50th state.

CURWOOD: Sure sounds like it. Hey, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: There's a plan that may be a win-win in the housing industry, and also a win for the failing recycled plastic industry: tiny homes, 3D printed from an average of 100,000 recovered recycled plastic bottles each.

The startup Azure Printed Homes 3D-prints tiny homes and backyard studios made of around 100,000 recycled plastic bottles. (Image: Courtesy of Azure Printed Homes)

CURWOOD: Wow. So you can use a 3D printer to make a tiny home; just how tiny a tiny home are we talking about?

DYKSTRA: Well, think about the size of a hotel room, 180 square feet, and the cost of such a room 3D printed would start at about $40,000.

CURWOOD: Hmm. So, I mean, tiny homes, well started as a fad, I guess they're kind of here to stay. But what are the odds that this could really catch on, do you think?

DYKSTRA: I don't know that a tiny home is for me, I'm a little too claustrophobic. But if you're talking about a second life for that many plastic bottles, it's worth looking into anything from short term rentals to homeless housing.

CURWOOD: And I imagine you could, you know, put a couple of these together in a modular fashion to build something bigger, huh?

DYKSTRA: Well, sure, if you can build them small, you can hopefully build them bigger. I think we're a little ways away from having a recycled plastic bottle, 3D printed Mar-a-Lago, and if we ever do that, hopefully we'll have the wisdom to build it more than five feet above sea level.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Alright, Peter, time now to go over to your vast store of history knowledge, and open up one of the volumes you see there and impart your knowledge.

DYKSTRA: We'll go from Hawaii to a quick stop in Mar-a-Lago to elsewhere in the south. September 6th, 1916 in Memphis, Tennessee, a man named Clarence Saunders opens the world's first self service grocery store, in which shoppers choose their purchases from well stocked shelves and place them in shopping carts, rather than relying on each individual item handed to them by a clerk.

CURWOOD: Hmm, well, that makes it easy to go and get a whole bunch of things in your shopping cart to kind of supersize your shopping trip.

1918 photo of the original Piggly Wiggly store in Memphis, Tennessee, which opened in September 1916 as the world’s first self-service grocery store. (Photo: Clarence Saunders, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DYKSTRA: That's right. And we go from this one store in Memphis, the anchor of what became the Piggly Wiggly chain. And we go from that to supermarkets everywhere and Costcos and giant food warehouses and everything we have today, that helps encourage over packaging, over consumption, over weight and over-everything.

CURWOOD: And at some point, maybe we'll get over this over consumption and bring things back to scale where we have a chat with the merchant from whom we are buying things, each and every item.

DYKSTRA: We'll have to look that over. But to start it all, we thank the Piggly Wiggly chain. Throughout the American south there are hundreds of franchise stores. You won't see "The Pig" in places like Malibu or in Hahvahd Square, or anywhere but throughout the South.

CURWOOD: Alright, Peter. Well, thank you. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org And dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, talk to you soon. Over and out.

CURWOOD: [CHUCKLES] And we have more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage, that's loe dot org.

Related links:

- Associated Press | “Hawaii Quits Coal in Bid to Fight Climate Change”

- Fast Company | “These Tiny Homes Are 3D Printed From 100,000 Recycled Plastic Bottles”

- Learn about the origins of the modern grocery store when Piggly Wiggly opened in September 1916

[MUSIC: Doobie Brothers, “What A Fool Believes” on The Best of The Doobies, Volume II, Warner Records]

Renters and Climate Change

Rental properties, like apartment buildings and the NY government housing complex pictured above, comprise more than a third of U.S. housing stock. 40% of the U.S.’s rental housing stock faces risk of damage from climate disasters, according to Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. (Photo: Avi Werde on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act that President Biden signed on August 16th there will soon be funds and programs for homeowners to take climate action by installing solar panels and energy efficient heat pumps. But renters typically use a third more energy per square foot than homeowners because landlords often don’t get a financial return on installing expensive upgrades to improve insulation and HVAC efficiency. And many renters are low income people who can ill afford higher energy costs. But there are ways for people living in rental housing to go greener, save energy costs and guard against heat waves and other climate related risks, says Todd Nedwick the Senior Director of Sustainability Policy at the National Housing Trust. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So we want everyone to be able to play a role in mitigating the climate crisis. A landlord, they don't always have that clear incentive to do so. So what kinds of carrots, or sticks for that matter, can help prod building owners to reduce their energy consumption?

NEDWICK: Sure, well, in terms of carrots, there are incentive programs out there, utility energy efficiency programs, for example, that will help to offset the cost of making building upgrades. Those are really important resources for building owners, especially owners of affordable housing, where there really is very limited cash flow to actually pay for the upfront cost of some of these upgrades. And we're also seeing policies like building energy performance standards, which basically require building owners of poor performing buildings to make upgrades to reduce energy use of the buildings. So we are seeing both carrots and sticks. I think what works most effectively is when you combine the two. So, if you're going to have a building energy performance standard and require building owners to make upgrades, especially in affordable housing, providing resources to the owner to actually pay for some of those costs is pretty important.

DOERING: And how do those incentives and standards work? Are they at the local level, the state level, the federal level?

NEDWICK: Yeah, so the standards are typically at the local or state level. And you know, building energy performance standards is a pretty new policy. There are several cities that have implemented building performance standards, and Maryland just became the third state that adopted a building performance standard statewide. And then for the incentive programs, typically those programs are at the utility level. So it's utilities that are providing those incentives to their customers. However, state public service commissions really make decisions that impact the utilities' motivation to provide those energy efficiency programs. Input from residents, from affordable housing providers, is really key to designing these programs in a way that's truly equitable, and achieves healthier, more energy efficient housing for everyone.

DOERING: So the good news is, even though it is a little bit harder for renters to make some of these changes, there are still things that renters can do. So if you're not a buyer, what are some of those sustainable changes that you can make to your residence?

Studies show that American renters use one third more energy per square foot than homeowners, generally due to poor insulation and outdated appliances. This can cause low-income renters to pay as much as 20% of their income in energy costs. (Photo: Jason Richard on Unsplash)

NEDWICK: Now, one opportunity for renters is community solar. We know that renters can't control the installation of solar panels on their building, but they can access community solar, which allows residents to basically purchase solar generation from a solar community. Renters can have control over, for example, improving the lighting in their unit, using more efficient lighting like LED, as well as talk to their landlord and encourage their landlord to participate in some of these energy efficiency incentive programs. It's unjust that for so many people, they're paying 10, 20% of their income on energy costs, it just leaves very little money for other essential needs.

DOERING: A lot of sustainable changes like weatherization, even some energy efficiency measures, may come with a significant upfront price tag. What resources are available to help landlords make these upgrades?

NEDWICK: Sure, so many utilities offer energy efficiency rebate programs, which helps to defray some of the costs of the building upgrades. There's also financing that can be available, a lot of green banks develop targeted financing programs for affordable housing, which provides the upfront resources that building owners will need to make those building upgrades. In terms of affordable housing, what we see is somewhere in the range of subsidizing 60 to 80% of the building upgrade costs.

DOERING: So, Todd, when my old landlord decided to put in a nice cedar closet upstairs, my roommates and I got a little worried about him using that to justify raising our rent. What provisions are in place to make sure this doesn't happen when, you know, a landlord installs solar panels or add some insulation?

NEDWICK: Yeah, so we see some programs address this challenge by essentially requiring as a condition of receiving funding to make building upgrades, landlords have to keep rents affordable, they have to agree not to raise rents as a result of the upgrades that are being made to the building. So, we think that is an important policy or important tool that should be adopted to really ensure that we're not passing on the costs of making these building upgrades to renters. And I think it also depends on how much funding the building owner is getting to pay for these upgrades. You know, if 100% of the cost of the upgrades are being provided through these programs, then there should be very little increase, if any, in the rents as a result.

Community solar is one practice renters can adopt to decrease their energy bills and invest in clean energy. Energy efficiency incentive programs can also provide funding for landlords to install solar panels on buildings. (Photo: Chelsea on Unsplash)

DOERING: So Todd, climate change is bringing increasing hazards from hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires. Given that 40% of the US's rental housing stock faces risk of damage from climate disasters, that's according to Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies, how is this set to impact renters?

NEDWICK: Climate change poses significant risks to renters, because a lot of the older rental housing stock is really not built to withstand climate impacts. And we see that where there are the greatest risks in terms of potential climate events, those areas of the country are typically disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and low income individuals. So we have to fortify the existing rental housing stock to withstand climate events and protect existing residents.

DOERING: Yeah. To what extent is disaster recovery going towards some of these low income and communities of color?

NEDWICK: In this country, we spend so much more funding on disaster recovery than we do disaster preparedness. And we've found that particularly rental housing, the disaster recovery funding often doesn't reach renters and owners of rental housing. Typically, disaster recovery programs allocate funding based on the extent of the economic disruption from a climate event. And so that often correlates with higher property values. As a result, a lot of the disaster recovery funding, especially through some of the FEMA programs, really don't reach affordable housing residents and owners in an equitable way.

DOERING: So we have this recent Inflation Reduction Act. What sorts of funds will be newly available to go towards the mission of making rental properties more climate friendly?

NEDWICK: So, the Inflation Reduction Act included a $1 billion program specifically targeted to the HUD housing stock that will allow building owners to invest both in the energy efficiency of the building as well as improve resilience. So we are really happy to see that level of investment and that targeted approach to addressing affordable housing. There are also programs in the Inflation Reduction Act that will provide rebates to both single family owners as well as multifamily building owners to encourage building owners to invest in energy efficiency, as well as converting existing fossil fuel burning equipment to all electric. Just to give you an example, in Washington, DC, where I'm from, buildings account for 75% of greenhouse gas emissions. So we're not going to address climate change if we're not addressing the existing housing stock. You know, climate policy is housing policy.

DOERING: You mentioned resilience. What do those kinds of things look like? Those kinds of upgrades that help a building be more resilient to climate impacts.

Todd Nedwick is the Senior Director of Sustainability Policy at the National Housing Trust. (Photo: Todd Nedwick)

NEDWICK: It includes, for example, flood proofing, elevating essential equipment above the ground level to prevent disruption to power, for example. Adding battery storage to buildings so that if the power goes out, we can ensure that there's still a source of power to help the residents. I mean, when you're talking about affordable housing, you're talking about residents who need essential services, in many cases, like maybe they have medical equipment that requires being powered, right. And so really ensuring that you are providing backup power sources. Another important resilience strategy is protecting residents from extreme heat. So adding cool roofs, for example, to buildings in order to really reflect the sun and prevent buildings from getting too hot.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, here in the city of Boston, I believe I remember hearing about air conditioning and reducing extreme heat in homes as like a human right.

NEDWICK: Yeah, and that is the new reality. I mean, in many cases, older buildings might not have air conditioning. And so in addition to providing incentives for reducing energy consumption, we also need to be providing resources to help building owners upgrade their buildings and install air conditioning to protect residents from extreme heat. We're seeing extreme heat disproportionately impact people of color, because they don't live in areas that have invested in and have the infrastructure to protect from rising temperatures.

CURWOOD: Todd Nedwick is Senior Director of Sustainability Policy at the National Housing Trust, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- The National Housing Trust | “Policy Brief: Key Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act for Affordable Housing”

- Learn more about the National Housing Trust

- Learn more about Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies

[MUSIC: Robert John, “Sad Eyes” on Love To Love, Capitol Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Tiger populations are increasing across parts of Asia. Their story just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington, “Take The ‘A’ Train” on Piano In The Background, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead, green voters in the midterm elections but first this note on emerging science from Hannah Richter.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note on Emerging Science: Tigers on the Rebound

There are now between 3726 and 5578 tigers in the wild, a 40% increase from 2015 estimates. Conservation efforts in Nepal, India, Bhutan, Thailand, Russia, and China are to credit. (Photo: Tengyart on Unsplash)

RICHTER: It’s the Year of the Tiger, and for the first time in 100 years, global populations of this beloved big cat have increased. The International Union for Conservation of Nature estimates that more than 5,500 tigers now live in the wild, up 40% from 2015 counts.

The countries of Nepal, India, Bhutan, Thailand, Russia, and China have all seen increases in their tiger populations. Nepal is the feline front-runner, with as many as 355 wild tigers, a tripling of their tiger population since 2009. In 2020, Nepal, home to the towering Himalaya mountains, broke the record for the highest altitude where a tiger was spotted two times, indicating that tigers may be claiming around 124 miles of new ground.

Main conservation efforts include working to connect tiger habitats across country borders, getting local people involved with forest stewardship, and removing snares to encourage tigers to move safely and freely across landscapes. Some tigers have also been relocated to boost mating, while in other areas, efforts to build populations of prey species using salt licks are underway.

Tigers are solitary animals with large territories, and space competition with humans has shrunk the amount of land that tigers can hunt safely. In 1900 there were as many as 100 thousand wild tigers. But over the last century, roughly 90% of tiger habitat - places like tropical rainforests and grasslands, have been destroyed. Habitat loss and poaching caused the tiger population to plummet to just 3800 wild tigers in 2000.

Unfortunately, as tiger populations increase, so too have tiger attacks. While they aren’t usually dangerous to humans, stressed tigers with limited hunting grounds can search for prey on the outskirts of their territory, where they are more likely to run into humans. Educating locals about tiger safety is an important part of new conservation efforts.

The IUCN does note that better sampling methods, like camera traps, are responsible for some of the improvements in tiger numbers. However, they reported in July 2022 that worldwide tiger numbers are “stable or increasing.” It’s a welcome win for these striped jungle favorites.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Hannah Richter.

Related links:

- World Wildlife Fund | “Wild Tiger Numbers Increase to 3900”

- NPR | “There Are 40% More Tigers in the World Than Previously Estimated”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Green Voters and the 2022 Midterms

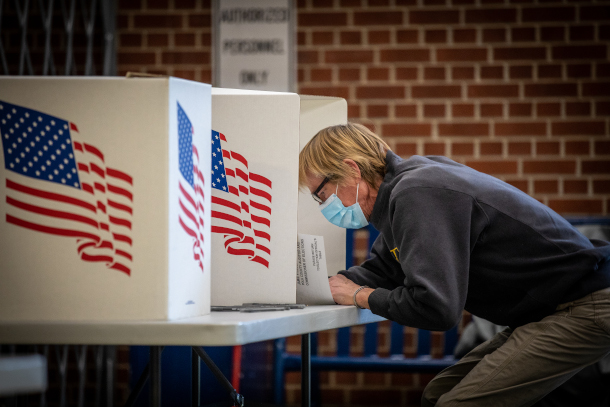

The Environmental Voter Project identified 33% of environment-first registered voters who did not plan to vote in the 2022 midterm elections. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: No doubt many voters for the upcoming mid-term elections are energized by the recent US Supreme Court decision permitting states to outlaw abortion, but climate- concerned voters could also make a small but still significant difference for who goes to the next Congress. Some polls suggest if the elections were held today Senate Democrats, now evenly split with the Republicans, may well increase their numbers, but the House could go either way. Those present slim margins squeezed through the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act earlier this year which is the first major US legislation to address the climate crisis. And to see if enough climate concerned voters will turn out to help keep climate action momentum going in the next Congress, we turn now to Nathaniel Stinnett founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Nathaniel!

STINNETT: Thank you so much, Steve. It's so great to be back.

CURWOOD: Great to have you. Now talk to me about the data you have that shows that in July, roughly a third of environment first voters were uninterested in voting in the midterm elections. If you had to speculate, why do you think that was the case?

STINNETT: That's right, Steve. So in July, before news of the inflation Reduction Act came out, we polled 3,300 registered voters in four battleground states. So Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. And we found a whole bunch of people, roughly about five or six percent of voters who listed climate as their top priority when choosing a candidate, but a whole third of them, so 33% of those climate-first voters, said they weren't motivated to vote in the upcoming midterms. And you ask why. And we actually have some pretty good data in the poll that tells us why they were really disappointed that Democrats in Congress weren't doing enough to address the climate crisis. And when I say they, not only were democratic climate first voters disappointed in congressional Democrats, but even 43% of independents said that they wanted Democrats in Congress to do more. So it's pretty clear: climate-first voters were disengaged, because Democrats in Congress weren't doing enough.

CURWOOD: So, with the passage of the inflation Reduction Act, which has what, some $370 billion worth of climate action baked into it, what do you think we'll see with environmental voter turnout now, in the upcoming midterms?

STINNETT: I think that there's very little doubt that turnout and enthusiasm will go up, it will go up pretty significantly. But let's keep in mind the denominator of the fraction too. I don't want to oversell this and make it seem like climate first voters make up, you know, a majority of the electorate. They don't, they don't, we're talking about, depending on the state five, six, seven percent of registered voters. So we in the climate movement, don't have nearly as much power as we need to have. And as we would like to have. But of those people who, whenever they vote, their top priority is climate, it seems pretty clear that they are now much more engaged and much more excited about voting than they were a month or two months ago. And we're starting to see that in some of the special elections. So the special elections recently in Alaska, but also in Kansas, and Nebraska, and Minnesota, and even some of the special congressional elections in New York. We see that young people, and to a lesser extent, people of color, and those are two demographic groups that make up the heart of the environmental movement, those two groups are really turning out in much higher numbers than we would otherwise expect.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was passed in the U.S. House of Representatives on August 12. All Democratic representatives voted yes to pass, while no Republican representatives did. (Screenshot: C-SPAN)

CURWOOD: And Nathaniel, say just a little bit more about who the environmental voters are.

STINNETT: So when we look at broad demographic groups, people who care deeply about climate and the environment, so these are people who are listing it as a top priority of theirs, they're much more likely to be women than men, they are much more likely to be young than old, particularly 18 to 34, they are much more likely to be Hispanic, or Asian American than white. Black voters are about about even though, they're not disproportionately more likely to care deeply about climate, but certainly Hispanic and Asian American voters are. And these climate first voters are much more likely to be lower income than upper income or middle income. So I just painted with four really broad demographic brushes. And obviously, there's a lot of interesting nuance when you dig further down. But by and large, we consistently see those four demographic trends.

CURWOOD: So you're talking, of course about registered voters, but this category can break down into likely and unlikely voters, which makes me curious how the unlikely voters stack up against the likely voters when it comes to the climate and environment.

STINNETT: Yeah, so I'm glad you brought that up, Steve, because it's so important. First, for your listeners to understand that, of course, who they vote for is secret. But whether they vote or not, that's public record. It's public record what elections you vote in, what elections you don't vote in. And if you're a politician who's trying to win the election, you better believe you're gonna run and look at those public records to figure out who has a history, who has a tendency of voting in this campaign that you're trying to win. And when you look at that, when you look at people's voting histories and break them down into people who are likely to vote in the upcoming midterms, and people who are unlikely to vote, the climate first registered voters are much more prevalent in that low propensity group, they're much more likely to be unlikely voters. And just to give you some examples, in this recent round of battleground state polling that we did, in Nevada, and Pennsylvania, two extremely important states this cycle, unlikely voters were twice as likely to list climate as their top priority, as likely voters were. And that means that turnout, voter turnout is going to be enormously important to the environmental movement this fall, not just in those two states, but in a lot of states.

Did you miss yesterday's Special Briefing on New York, the Midterms, and Environmental Voters?

— Environmental Voter Project (@Enviro_Voter) August 16, 2022

Don't worry, we've got you covered!https://t.co/nsXwmNK7Tw #ActOnClimate #ClimateCrisis #ClimateEmergency #ClimateActionNow #ClimateAction

CURWOOD: So why do you think so many climate environment first register voters are are so unlikely to vote?

STINNETT: You ask a million dollar question, Steve. And it's hard to answer because when you ask people why they aren't doing something, usually they give you the socially acceptable answer, they usually tell you what they think you want to hear. The honest answer is we don't know for sure, but we have a few hints of what's going on. The first is, as I mentioned before, the demographic trends that we see among these climate first voters, so they're younger, they're more likely to be people of color, and the more likely to be lower income. Well, what are those three groups have in common, they're all less likely to vote than the average voter. And a lot of that has to do with voter suppression. If anybody anywhere is trying to make it harder for someone to vote, chances are, they're targeting young people, people of color, or poor people. And that really hurts the political strength of the environmental movement every time there's an election. But the second thing that we think is going on, is for over a generation, the environmental movement has been strangely, apolitical. And I know that sounds pretty controversial. So let me explain what I mean by this. Chances are, when you grew up, you thought of environmental activism as picking up your litter, or changing what you eat, or changing how you get to work, or changing the electricity you consume, or something that had to do with your personal behavior. And you would never, ever hear someone who cares about gun rights or reproductive rights talk in such a strangely apolitical way. And this is not by accident. I mean, for decades, the fossil fuel industry has run very sophisticated PR campaigns, essentially trying to tell all of us "Don't pay attention to that coal fired power plant back there. It's all your fault, Steve, for having a plastic water bottle in your hand." Right? Like they're trying to blame us for these large systemic crises. And in many ways, we fallen for it, and we've become apolitical, and we blamed ourselves, rather than these big systemic actors. It not only keeps them from organizing around particular candidates and particular campaigns, it keeps them from even thinking about environmental or climate concerns as in the political realm. We've got a lot of sort of institutional memory to cut through. We have to try to convince people that actually politics is where the most important climate and environmental victories can be won and lost.

In two battleground states, Nevada and Pennsylvania, the Environmental Voter Project found that unlikely voters were twice as likely to list climate as their top priority, as likely voters were. (Photo: cyclotourist, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So given this $370 billion commitment to climate action under the Inflation Reduction Act, to what extent are environment and climate first voters are aware of the need to keep certain people in Congress in order to consolidate those gains. In other words, some would say that 370 billion is really just kind of a downpayment, that unless it's sustained with further action, that won't really amount to all that much.

STINNETT: Yeah. So I think you are objectively right, Steve, that a lot of people, I think, rightly view it as only a downpayment. And I also think you're right in asking, well, how aware of that are people who care deeply about climate and the environment. And there's very little data on that, but the little data that there is shows, they're not that aware of it. In fact, they're not even that aware of the Inflation Reduction Act beyond it simply being the first big climate win that we've had ever, to be honest. I mean, this is, without a doubt the largest piece of federal climate legislation in American history. And that is a really shallow understanding of what just happened and what needs to happen. But that is enough to turn non voters into voters. If you think of sort of the hierarchy of emotions that drive people to the polls. Usually, and none of us like to admit this, but it's true, if you get people angry, boy, does that make them good at voting. Then after getting them angry, getting them excited is almost as good. But the worst thing, the worst thing for voter turnout, is if they're disappointed. And I know from looking at a lot of this polling data, that there were a lot of environmentalists who spent the last year and a half disappointed, and that means they weren't going to show up. And now, a lot of them are really, really excited. Not because they have an in depth understanding of what the inflation Reduction Act means and what more we need. They don't. But because for the first time in a while, the wind is in their sails, and that means a lot and that gets people excited to vote.

CURWOOD: People like winners.

STINNETT: People like winners. Absolutely.

CURWOOD: There's not a huge number of voters who put the climate first, the environment first. But of course, when elections are tight, any segment that leans one way or the other can make a huge difference. So using that lens, what are some states to keep an eye on during these midterm elections?

As President Biden’s National Climate Advisor, I couldn't be more excited about the Inflation Reduction Act.

— President Biden (@POTUS) August 19, 2022

From securing a cleaner future for young people to advancing environmental justice for communities overburdened by pollution, this is a big step forward. –@ginamccarthy46 pic.twitter.com/c7OoWVDS3G

STINNETT: Because of their redistricting map getting thrown out at the last minute and having to be reworked, there are, depending on which prognosticator you look at, anywhere between eight and ten competitive US House seats in New York. And that is a huge number. I mean, I'd go so far as to say, control of the House of Representatives might be decided in New York State this fall. And so New York, especially up along the Hudson Valley, and out along Long Island, there are eight of those competitive seats just in those two areas are going to be really decisive, in part because New York usually isn't a battleground state. We've identified over 1.1 million super environmentalists in the state, who never vote in midterms. And that is a huge number in a state where there are only 13.4 million registered voters and only 6 million showed up last time there was a midterm. So this is a state that is going to be very important. And also environmental turnout is going to be very important.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, there's been a lot of talk surrounding voter turnout these days, from voters who prioritize abortion rights and voting rights, famously the constitutional question in Kansas pulled all kinds of people out to vote. Nathaniel, what overlap, if any, do you see between those voters and environment-focused voters?

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

STINNETT: We see a lot of alignment, in northeastern states, in particular, among people who list abortion rights as one of their top priorities and people who list climate change is one of their top priorities. So for instance, in Pennsylvania, if you list climate change as one of your top priorities, abortion rights is the next most likely issue that you will list as a top priority. Now, it isn't like in the southeast, or the southwest, there is no alignment. We just see that alignment as being the strongest in the middle Atlantic and northeastern states. So Maine, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, to a lesser extent, Virginia, places like that. But in all parts of the country, there is a lot of alignment. And again, that gets back to some of the demographic correlations that we were talking about, Steve. If you care deeply about climate change and other environmental issues, you're more likely to be a woman than a man, you're more likely to be young than old, you're more likely to be a person of color than white, and you're more likely to be lower income than middle or higher income. And those are the four demographic groups that also care the most about abortion rights. And those are the four demographic groups that are most likely to be impacted by removing easy access to abortion. And so yes, we see a lot of overlap there. But it's at its strongest in the mid Atlantic and northeastern states.

CURWOOD: Well, we'll all be watching, I guess, come the night of that second Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Nathaniel Stinnett is the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

STINNETT: Thank you, Steve. It's always a pleasure to join you.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Environmental Voter Project

- Environmental Voter Project | “Battleground State Poll: new data on voters in AZ, GA, NV, and PA”

- Read more on the Environment Voter Project’s polling data

[MUSIC: Earth Wind and Fire, “September” on The Best of Earth Wind and Fire, Wind & Fire Vol.1, Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, California bans the sale of most new gasoline cars by 2035.

LOPEZ: California’s transportation sector, accounts for about 40 to 50 percent of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions. The new rule will significantly reduce passenger vehicle emissions by more than 50 percent by 2040.

CURWOOD: And California’s embrace of electric vehicles will likely ripple across the country. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Earth Wind and Fire, “September” on The Best of Earth Wind and Fire, Wind & Fire Vol.1, Columbia Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Hannah Richter, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth