September 30, 2022

Air Date: September 30, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Spending Czar

View the page for this story

The job of getting the biggest climate bill in U.S. history from concept to action will largely fall to White House veteran John Podesta. As senior advisor to President Biden for clean energy and implementation, he’ll need to coordinate numerous agencies, including the IRS and Treasury, given that around ¾ of expenditures run through the tax code. Harvard economist Joe Aldy joins Host Steve Curwood to explain. (13:10)

Steady Light for Solar

View the page for this story

For years renewable energy has had on again, off again financial support from the US government, limiting its development to fight the growing climate crisis. Those days appear to be over now that the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act provides a decade of tax breaks and funds for clean energy. George Hershman, CEO of SOLV Energy, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss this new day for solar power. (09:40)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb celebrate Kenya as a new clean energy champion thanks to its abundant geothermal resources. Also, the US finally ratifies the Kigali agreement, which phases out hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), which are potent greenhouse gases. This week also saw the passing of David “Dave” Foreman, an eco-warrior who co-founded Earth First! group back in 1980. (04:41)

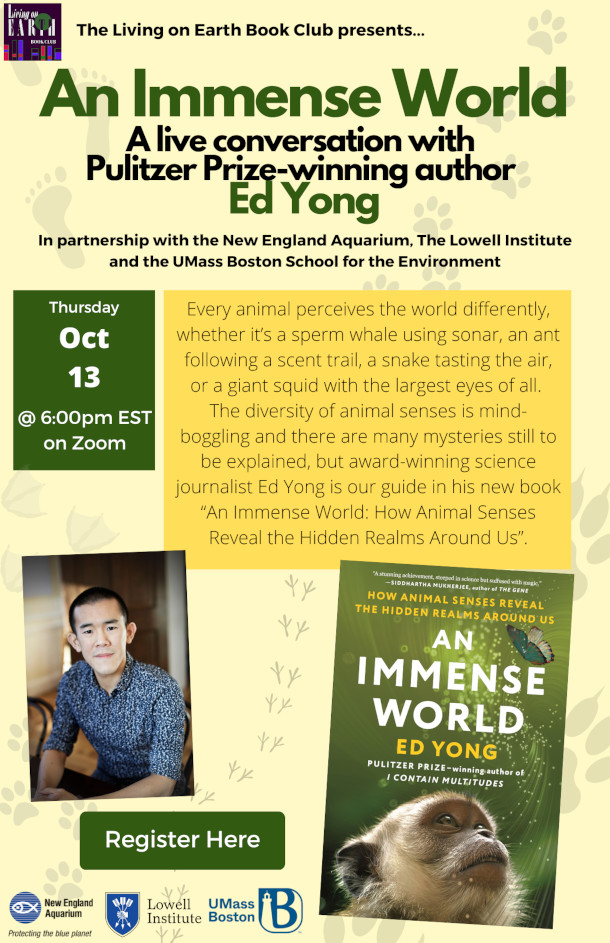

Our Next Event in the LOE Book Club

The Living on Earth Book Club, New England Aquarium, Lowell Institute, and UMass Boston School for the Environment proudly present this free, live conversation between Host Steve Curwood and Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer Ed Yong on his bestselling new book, "An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us." Join us online on Thursday, October 13th at 6:00pm EST. ()

Extinction Threatens 1 In 6 U.S. Trees

View the page for this story

1 in 6 U.S. tree species are at risk of extinction, largely due to pests and disease, according to a recent study published in the journal Plants People Planet. Lead author Abby Meyer joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how climate change threatens American forests, and how conservation efforts can help. (09:31)

The Grand Canyon of the Atlantic Ocean

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Hudson Canyon is a vast underwater gorge and ecological hotspot with deep-sea corals that’s being considered for national marine sanctuary status. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering called up Merry Camhi, director of the New York Seascape at the Wildlife Conservation Society and New York Aquarium to learn more about what protecting Hudson Canyon could mean. (09:23)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220930 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Aldy, Merry Camhi, George Hershman, Abby Meyer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

How clean energy tax credits to increase wind and solar capacity could be the gifts that keep on giving.

HERSHMAN: If we produce low-cost energy in this country, we will manufacture more, because manufacturing traditionally moves to low-cost energy markets as much as it's moved to low-cost labor markets.

CURWOOD: Also, roughly one in six trees in the United States is threatened with extinction.

MEYER: We identified 165 threatened tree species in the US. And lots of those are pretty well-known species like oak trees, ash trees, the Frasier fir which is a really common Christmas tree.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate Spending Czar

Former White House Chief of Staff John Podesta at the 2019 National Forum on Wages and Working People hosted by the Center for the American Progress Action Fund and the SEIU at the Enclave in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

And I’m Steve Curwood.

Ultimately it took a year and a half for the core of President Biden’s climate agenda to finally get through Congress, and now the hard of work of putting it into practice begins. The Inflation Reduction Act now allots $370 billion over the next ten years to address the climate crisis, and the job of getting from concept to action will largely fall to White House veteran John Podesta. His official title is now senior advisor to the President for clean energy innovation and implementation. For more about John Podesta and his task, I’m joined now by Joe Aldy, a former colleague and Harvard economist who worked for President Obama on energy and the environment and served on President Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers. Welcome back to Living on Earth Joe!

ALDY: Hi, Steve, it's good to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me, what does John Podesta bring to the weighty role that President Biden has tasked him with?

ALDY: Well, President Biden and the Biden administration have a very large law to implement. And I think in bringing in someone like John Podesta, who has a lot of experience -- former Chief of Staff to President Clinton, worked as a senior advisor leading efforts on climate change in the Obama administration as well -- he is someone who has, clearly, the ear of the President. So when he speaks, say, to members of the Cabinet, to say we need to move faster and smarter in implementing the law, people recognize he's speaking on behalf of the President. He's someone who can reach out to stakeholders, to members of Congress, to the public to be able to demonstrate and make the case for what the Biden administration is doing in implementing the law and advancing the President's decarbonization agenda.

Wind turbines in California’s Mojave Desert (Photo: Anthony Quintano, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, I have to confess, I haven't read all, what, nearly a thousand pages of the Inflation Reduction Act, but it seems that many of the provisions are related to tax credits. So at the end of the day, of course, Treasury and the IRS are going to be looking at it. What's going on here? And how can John Podesta wrestle with making sure that these tax provisions are implemented?

ALDY: Right, so we have in the Inflation Reduction Act about $370 billion of spending, or what we call tax expenditures. Basically, tax credits for clean energy and climate. About $270 billion of that $370 billion are for tax credits. So there's about 3/4 of climate spending runs through the tax code. And part of that reflects, just historically, we have often used the tax code to subsidize everything from putting solar panels on your roof, to building wind farms, to buying a more energy efficient furnace for your home, or buying an electric vehicle. So a lot of this is extending, although with some important changes, extending the way we've used the tax code in the past. And part of that just reflects the way this bill was crafted under budget reconciliation. Budget reconciliation doesn't give you the opportunity to craft whole new regulatory authorities. It basically has to focus on a way in which we either raise money or spend money. So that's why I think there's a large emphasis here on tax credits. So part of it is that making sure that as John Podesta is organizing the efforts in the federal government, is seeing where there may be opportunities for different parts of the government to assist Treasury and IRS in implementing these new tax provisions. Some of these tax provisions, for example, that are new include giving bonus credits if you build a wind farm, if you can demonstrate that you are satisfying local labor market requirements, the prevailing wage in the local labor market, and you have a labor apprenticeship program. The Department of Labor has helped with those kinds of programs in the past, they may be able to advise Treasury on something like that. There may be cases where the Department of Energy can help advise IRS and Treasury on new technologies to make the case for why they may qualify for specific tax credits. So part of what I think Podesta can do is help IRS and Treasury get smarter, faster, in how they design the guidance and the rules for how they're going to implement these new tax provisions.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, some of the tax credits in this new law are transferable. How's that going to work?

May 2008 photo of John Podesta, left, and President Joe Biden, who was a Senator running for the Vice Presidency at the time. (Photo: Center for American Progress, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

ALDY: Traditionally, a, say, a wind farm would get in today's terms, about 2.5 cents for every kilowatt hour of electricity that produces. It's a pretty sizable subsidy, and for most wind farm developers, it's more than what they owed Uncle Sam in taxes. And the problem is, if your tax credit is greater than what you owe in taxes, you can't take the full value of the tax credit, you're limited by how much money you owe in taxes. And so typically, in the past, these wind farm developers would partner with a large financial company, like a big bank, a big investment bank that often has large tax obligations every year, tax liabilities. And so that bank would provide equity for the project, and instead of being paid out of revenues, they get paid by being able to claim the tax credits. The challenge is when you're trying to cut emissions so dramatically and drive out really rapid deployment and rapid investment over the next few years, there's a question about whether or not there's enough of that market to meet the needs of wind and solar developers and so on. So instead, in this law, they've said, if you are building a new wind farm, you can sell your tax credit to someone else. And that's going to make it a lot more flexible and a lot easier for the wind farm developer to get that monetary value associated with the power they're producing and sending out onto the grid. So it's something new, I think there may be some challenges in trying to get this market up and running, because you're going to have a bunch of wind farms and solar facilities trying to learn “How do I sell this thing? Who's out there willing to buy it?” And then buyers trying to make sure they understand what it is they're buying. Because with this law, if there's a wind farm producing so many kilowatt hours of electricity, the question of how much that's worth depends on whether they are using domestic manufactured content, like are their turbines made from US-manufactured steel and whether they're satisfying local labor market prevailing wage conditions and apprenticeship programs; whether they've located in a so-called "energy community,” which has traditionally been a fossil fuel community. All these give you larger tax credits, larger value per kilowatt hour of wind that's being produced. So, I think there's gonna need to be a little bit of work to try to figure out how this market will work. It could be a big market, we're talking tens of billions of dollars a year that may transfer through this new approach to tax credits.

CURWOOD: Let's talk a bit about environmental justice here. So often, say, a highly polluting coal fired power plant is upwind from disadvantaged communities. How can a firm that, say, a solar farm goes up and displaces such a thing, how can that solar farm get some credit for helping folks in those communities breathe easier?

ALDY: So part of this is a challenge in how you design policy to target different parts of the country. And there are some provisions some that target energy communities, some that target low-income communities, in the Inflation Reduction Act. But many of the provisions are, in a sense, kind of generic in the sense that they apply nationwide. Now, it may be that as we move forward, we can get a sense of where, if we have a way of sort of collecting the necessary data and analyzing it, at risk of sounding like the public policy wonk that I am, [LAUGHS] like, this is really important; this is really important to get the data and figure it out, and be able to understand that. You know, in some sense that solar facility, if it's going in, it's driving down the price of electricity in the local market. And as a result, it makes it no longer economic for that nearby coal fired power plant to operate. Its benefit is that it is enjoying the value of the tax credits, and it is now generating revenues in the local market. But in a sense, they don't get any sort of additional benefit, if they are reducing, by driving out coal fired power plant, pollution in a nearby community. And I think that is, that is something that may be worth thinking about how we may design the next generation of policies that can do that. You know, this bill has been described fairly as by far the largest energy and climate bill we've ever passed. Yet we also know it's not enough, it's not going to be enough on its own to deliver the President's goal to cut our emissions by at least half by 2030. Or the longer term net-zero goal we have for the economy, we know we'll need to do more. So that's why I think it's important for us to evaluate the performance of these policies. I think that's going to give us the evidence to design much more effective policies in the next round. That'll enable us to think through how to target some of our policies to deliver those benefits to underrepresented communities and low-income populations as well.

The U.S. Treasury Building in Washington, D.C. About three quarters of the expenditures in the Inflation Reduction Act run through the tax code as qualified tax credits that the U.S. Treasury and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) will disburse. (Photo: Ken Lund, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So please, can you give me an example of some of the data that will be very helpful to collect?

ALDY: Right, so let me identify two things. One is with electric vehicle tax credits. We have tax credits both for new vehicles and used vehicles. And so here, IRS is probably gonna have to collect so-called VINs, the Vehicle Identification Number that's unique to every vehicle, so that we know there's not any kind of double-dipping or more of these tax credits. So you can't get it for both buying it new and then buying it used. If we can get that information and also know where you bought the car, that also helps us better understand where EVs are penetrating. It may help us actually be more effective in how we target some of the money in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that's trying to roll out EV charging stations. It may also help us better understand how those benefits are going to accrue to various communities across the country. The other thing that I think is important is with the subsidies for renewable power. If we just know where these facilities are, and the tax credits that they're claiming, which right now, you don't actually have to put that information when you claim these tax credits in your tax filings. If we just know where they are and how much they're claiming, that's going to enable us to use a lot of our existing tools to understand how that's going to improve air quality across the country.

CURWOOD: There's only, what, two and a half years left in the present administration. How the heck do you get all this done? And by the way, obviously that $370 billion doesn't go out in just these next two years. It's over, what, I think a 10 year period. But how do you get some consistency in this with the possibility the administration could change in a couple of years?

President Barack Obama meets with John Podesta, Counselor to the President, in the Oval Office, Jan. 29, 2015. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

ALDY: So one thing we've learned even when we have switched administration's in the past, we don't go back and undo tax credits. This is part of the advantage of actually if, when you provide enough subsidy to key economic interests, they will make sure that's not undone. There have been challenges in the past on extending, say, tax credits for wind and solar because they often have sunset provisions, just like they do in this bill, they sunset in a decade. But I, you know there's a sense in which tax credits tend to be durable, even when we see parties change hands. And part of it, too, is the production tax credit for wind was originally a bipartisan deal. Senator Grassley of Iowa is actually quite fond of the tax credit for wind, in part because his home state of Iowa produces a lot of wind power. Also, because by going through the tax code, there's very few opportunities for someone to go to the courts to challenge the tax code, in contrast to how we've thought about courts being used to challenge, say, new regulations issued by federal regulators. Congress doesn't really delegate much discretion to IRS and Treasury in the tax code, they will need to do a little bit in terms of I think, sort of, if you will, the sort of technical design and implementation. But as a result, there's very little for you to hang your hat on to say, “This is something I can challenge in courts.” So I think as a result, a lot of these policies are going to endure over the course of the next decade.

CURWOOD: Joe, to what extent is this Inflation Reduction Act on the scale of a "new deal" for the climate?

Joe Aldy is an economist and professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Aldy)

ALDY: So it's a lot more than we've ever done before, and it falls short of what we need. So that's the challenge we face. I know there are some activists who feel like we need a lot more, we needed to spend a lot more. There are some who are frustrated about some of the compromises in this bill, for example, some of what was done with respect to oil and gas leasing on federal lands. I think it depends on what you think the alternative scenario is. For me, the alternative scenario is you don't get any new spending out of this Congress on climate. And in that sense, this is unprecedented. And it's a significant next step on climate policy. But when we think about climate policy, it's not going to be like one big legislative bill, and we've solved the problem. We're gonna have to keep tackling this issue. And we're gonna have to be using all of our authorities throughout the government, we're gonna have to think about ways we partner with state governments and with the private sector, to continue to drive out low carbon technologies, to think about ways we can help people better adapt to a changing climate. There's a lot more that needs to be done. I guess one way to think about it, if you want to draw the analogy to the New Deal, is that in the 1930s, there were actually a lot of pieces of legislation passed over a number of years that constitute what we think of as the New Deal. So I think this is like the first really big piece of legislation in our new sort of climate-oriented deal, if you will, but we're gonna need more as we drive down our emissions, and try to deliver on our goals for 2030 and beyond.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is a professor of economics at the Harvard Kennedy School. Joe, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

ALDY: Thanks, Steve. It's been my pleasure.

Related links:

- Read Professor Aldy’s paper, "Learning How to Build Back Better through Clean Energy Policy Evaluation."

- AP | “Biden picks White House veteran to run revived climate drive”

- Read the Inflation Reduction Act

[MUSIC: Diana Krall, “Almost Blue” on Artist’s Choice-Elvis Costello, by Elvis Costello, Hear Music/Universal Music Enterprises]

BASCOMB: Coming up – how the new federal funds and tax credits for renewable energy are supercharging the solar power sector. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Toby Walker, “Hey, Good Lookin’” on Hand Picked, by Hank Williams, Band In the Hand Records]

Steady Light for Solar

After years of ever-changing policies surrounding clean energy, the solar industry now sees 10 years of consistent policy ahead to build stable businesses and industry around. (Photo: coniferconifer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

For years, solar and wind power have had off-again-on-again financial support from the US government, limiting renewable energy development to fight the growing climate crisis. Those days are now over. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act ends federal financial stuttering for renewable energy with a ten-year commitment for tax breaks and funds to boost innovation and industrial development. George Hershman is the CEO of SOLV Energy, a company with 4,000 employees that installs utility scale solar arrays. And now with the money and tax credits of the Inflation Reduction Act coming online, his company, and just about the whole renewable energy sector, are looking toward explosive growth. George Hershman, welcome back to Living on Earth.

HERSHMAN: Thank you for having me back, Steve. This is a pretty exciting time.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. Now, we talked to you earlier this year about the interruption of solar panel importation from Asia that President Biden has now lifted those restrictions for the next two years. So today, we want to ask you about how the big Inflation Reduction Act affects the outlook for your sector and your business. First, what does this mean for your line of business?

HERSHMAN: Well, this is really historic legislation for the solar industry. And so when I look at the industry as a whole, I think every sector has been addressed. There's really three kind of market sectors that we look at from a solar standpoint. We've got a residential market, a commercial market and the utility scale sector, which is where our company operates the most. But all three of those sectors have received, you know, a lot of support through this bill. That is exciting for me is the fact that we have 10 years plus of consistent policy that we can build businesses and industry around and, and really make the historic change that we need in this country to address climate change through clean energy.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the scale of the manufacturing stimulus. Is what's been laid out in this legislation going to be sufficient for the demand you expect to see in the years ahead?

The IRA bill introduces tax credits for domestic manufacturers building solar energy technology to improve the domestic supply chain for the solar industry. (Photo by: Qatar Solar Energy, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

HERSHMAN: Well, the way that it's structured is a performance tax credit. So the more you build, the more tax credit that manufacturers get. So, it's really built for scale. It's intended to build large scale plants to meet the demand. That will take time. We will likely not have that manufacturing online, to meet all of those goals. So it's still going to be an industry that relies on, you know, a portion of imports for its installation. But this bill does a lot to start to build factories. We're already hearing multiple manufacturers make announcements of either new plants or expansion. Now we have this support and legislation that's in line with what we all ultimately want, which is a stable supply chain that we can rely on and build here domestically.

CURWOOD: So George, what's your best guess as to the total amount of renewable energy we need to get online every year to hit the targets that have been set? And how does that compare to say what a coal fired power plant can turn out?

HERSHMAN: So you know, by all estimates, we need to, by the end of the decade, start to put in 70 to 80 gigawatts of renewables in the ground every year to replace the decommissioning, coal and gas fleet, as well as to supply new load for the demand that will be added due to the electric car fleet. So in comparison, a traditional coal plant is somewhere between two to three gigawatts. So you can imagine we're going to replace, you know, 50 of them annually.

CURWOOD: Now, what about jobs in this renewable energy sector now? What do you see in this next five to 10 years in terms of more jobs?

HERSHMAN: This is a massive job creation bill. We've seen as high as 2 million new jobs. I've seen numbers with manufacturing and wind that say, you know, eight to 10 million jobs. So this is a clean energy bill on top line, but it's really a job creation bill on the bottom line.

CURWOOD: Now, let's talk about your own business. What's changed now that you're not looking at the inability to import solar cells, when in fact, there's this huge stimulus from the federal government? What's changed for you, and what projects are you now taking on?

The solar industry sees the creation of millions of jobs as the federal government supports the industry through the newly passed legislature. (Photo by: Renovus Solar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

HERSHMAN: The forward-looking forecasts in the business are to grow it three or four times the size it is today, just to stay at pace with our customer demands. We're also looking at, you know, how do we provide all of the service offerings that our customers need as this market grows so large. This has traditionally been a business that has a three to five-year runway. We usually look at it in very short blocks because we get an investment tax credit for five years and it starts to tail off. So then there's a ramp-up-ramp-down cyclical nature of this business over the last 12 years. Well, now you can look into the future and you know exactly what the business model is going to look like. And it is just, you know, it is straight up.

CURWOOD: George, what in the way of new technology would you like to see over these next years?

HERSHMAN: The IRA legislation addressed investment tax credits for hydrogen and as well as emerging technologies. I think one of the ways that the bill was structured uniquely is that after five years, the investment tax credit, which currently is set for wind and solar, in five years, it transitions into a techneutral ITC, which basically says any technology that decarbonizes energy production can receive an investment tax credit. So that leaves it open for new technologies and new inventions as we move forward so that we don't stay stagnant in a clean energy development. I like the fact that we're incentivizing inventors to think outside the box and think of what is the next technology, let's don't pick winners and losers. And let's let the market figure out what we're going to do five years from now.

CURWOOD: Right now, as we're talking, George, the financial markets are kind of unhappy, and people are talking about recession. What is your gut tell you about what this legislation in the whole build out of a new generation of a way to generate electricity will address what appears right now to be economic woes in this country?

HERSHMAN: Well, I think that it addresses a lot of the needs we will have going forward. It's hard to say that tomorrow, we're going to point to something that this bill did that change some of the challenges we have today in a supply chain that is coming out of COVID. There's just a global kind of restructuring. But some of the things that we face, just structurally, like, you know, manufacturing that's moved overseas, that's hurt our supply chain, this brings a lot of that manufacturing back. If we produce low cost energy in this country, we will manufacture more because manufacturing traditionally moves to low-cost energy markets as much as it's moved to low-cost labor markets. And so because we are efficient from a manufacturing standpoint, and we can do it with low-cost energy, we're going to build a manufacturing infrastructure. Again, we're already seeing that we supported it in the CHIPS bill, you're going to see CHIPS coming back here. Now you're going to see solar supply chain coming here. We're just going to see an onslaught of manufacturing and business creation that will ultimately make us stronger in the long run.

CURWOOD: George, I got to ask how you feel now in the wake of this Inflation Reduction Act being passed is the appropriate scientific term? Wahoo!

HERSHMAN: Yeah, I think so that I'll go with that one. I'm excited. The industry's excited. While we're very excited, and we got together last week as an industry at RE+, which is the biggest conference in the country around energy and renewable energy, I think the message was was interesting. It was, “Let's celebrate. Let's take a victory lap. Let's pat each other in the back, and then let's put our head down and get to work because we have a lot of work to do.”

CURWOOD: George Hershman is the CEO of SOLV energy. Thank you so much, George, for taking the time with us today.

HERSHMAN: Absolutely. Thanks, Steve. I appreciate the time.

Related links:

- Learn more about solar tax credits

- More on the numbers of what the Inflation Reduction Act includes

[MUSIC: Johnny Nash, “Bright Shiny Day” on I Can See Clearly Now, by Johnny Nash, Epic Records]

Beyond the Headlines

The Olkaria III geothermal power plant complex in Kenya. (Photo: Geo Rising, Patrick Walsh, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. We have a couple items that are good news in a way, but they also come from a completely different angle than we're accustomed to. The first one, about a clean energy leader from Africa. Kenya has become the world's leader in geothermal energy.

BASCOMB: Wow. So what are they doing right there?

DYKSTRA: They've got a little head start that they started looking into 70 years ago, because the Great Rift Valley, so significant in anthropological and scientific terms, as one of the areas where human evolution is said to have made its major leaps, is called the Great Rift Valley because it's literally pulling apart, releasing energy, releasing heat. And that's the place to look to turn that heat into energy. In recent years, Kenya has gotten as much as 48% of all its electricity from geothermal.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's amazing. And yeah, it makes sense. I mean, that's where these two plates are pulling apart, it makes the Earth's crust that much thinner and easier to access geothermal energy. What else do you see for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Back in the 80s, the US and the UK became leaders unexpectedly in the push for the Montreal Protocol, the highly successful treaty to limit ozone depletion by limiting CFCs, chlorofluorocarbons. Recently, the Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol was passed by 137 nations. The US wasn't the leader, they were the laggard, they just became the 138th country to pass Kigali. And what Kigali is, is a limit on hydrochlorofluorocarbons, also used in refrigeration and air conditioning. They were very, very potent greenhouse gas, short lived and very potent as an ozone layer killer.

Most hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) have been phased out, although some continue to use it to service refrigerators and air conditioners and in fire suppression. (Photo: PizzaToast, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: My understanding is that we've pretty much already phased out HCFCs. And so it was kind of a name only that we've now ratified the agreement. But why now? Why after one hundred and, did you say, 38 other countries that have already done it? Why are we getting on board with this now?

DYKSTRA: The US is the 138th. And it came about in part, you think of the United States Senate and Congress in general, as being in absolute lockdown for not approving anything environmental, if they can help it, the Senate and for the time being minority leader Mitch McConnell would block any such thing. But out of the blue, the United States Chamber of Commerce, a staunchly anti-regulatory body, sent a letter to members of the Senate urging that they all vote in favor of ratifying the treaty. The Republicans did as they were told by the US Chamber, they came around, and the US Senate has ratified the kind of thing that they've absolutely resisted in recent years.

BASCOMB: Well, better late than never, I suppose. What do you see for us from the history books this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Not a historical item, but something about a man who made history who passed away last week. Dave Foreman, if you haven't heard of him by name, you probably know his work. Dave Foreman was one of the co-founders of Earth First!, the consummate group of environmental hellraisers.

BASCOMB: Dave Foreman, his approach was somewhat controversial. I mean, putting sand in gas tanks of bulldozers and things like that, but he got attention and he got results, too.

Dave Foreman (Photo: Courtesy of the Rewilding Earth Podcast)

DYKSTRA: They did and they have since the 1970s. Dave Foreman later spent decades first founding and then running the Rewilding Institute, dedicated to restoring land to its natural state, something that a lot of people in the environmental community have given up on given that there's so much influence of the human hand on the entire planet.

BASCOMB: Well, that's certainly true. All right, well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Reasons to be Cheerful | “How Kenya Became the World’s Geothermal Powerhouse”

- Los Angeles Times | “Eco-warrior Dave Foreman dies; co-founded Earth First!”

- Learn more about the Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & The Silk Road Ensemble, “Blue Little Flower” on Silk Road Journeys, Chinese Traditional, Sony Classical]

Our Next Event in the LOE Book Club

Join us on October 13th for a live book club event with Ed Yong.

CURWOOD: Beetles that are drawn to fire and fish that “talk” to each other with electricity. Wonders like these abound in science writer Ed Yong’s new bestselling book, “An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us”. Ed Yong will join the Living on Earth Book Club on October 13th for a free, livestreamed conversation, and you’re invited! For details and to register for the event go to loe.org/events.

Related link:

Find out more and register for this upcoming live event

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & The Silk Road Ensemble, “Blue Little Flower” on Silk Road Journeys, Chinese Traditional, Sony Classical]

BASCOMB: Coming up – As many as one sixth of American trees species are at risk of disappearing. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rebirth Brass Band, “Just the Two of Us” on Ultimate, by Macdonald-Salter-Withers, Mardi Gras Records]

Extinction Threatens 1 In 6 U.S. Trees

Between one in six and one in nine American tree species are threatened with extinction, according to a new study in the journal Plants People Planet. Some of those threatened species are iconic California redwoods (pictured above) and giant sequoia. (Photo: James Lee on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Hundreds of scientists from botanic gardens and research institutions across the U.S. recently collaborated on a study assessing the extinction risk of all 881 known American tree species. The study, published in the journal Plants People Planet, found that between 11 and 16% of American trees are threatened with extinction. The top threats to trees are pests and disease, and climate change is expected to increase that risk. Abby Meyer is the Executive Director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. and a lead author on the study.

MEYER: The impacts of climate change on average are, you know, warmer temperatures, droughts, more intense storms and natural disasters. And that makes species and entire ecosystems more stressed and more vulnerable. And climate change can accelerate the invasion of pests and diseases actually into these weakened forests.

BASCOMB: So trees that are vulnerable, because the climate isn't quite suitable for them anymore, are also more vulnerable to being invaded by pests and things?

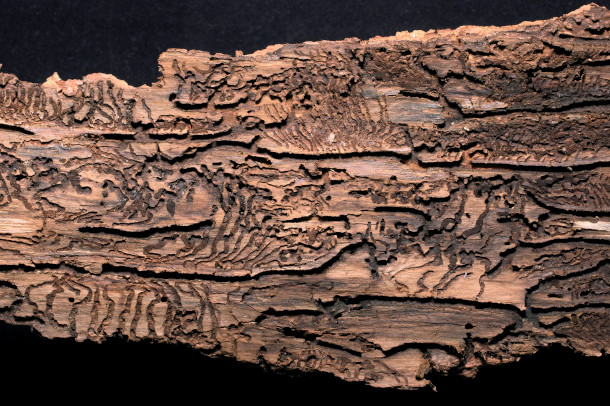

MEYER: Yes, exactly. For example, bark beetles, which are one of the largest animal families in the world, surprisingly, they often attack trees that are weakened, so there will be their first target.

BASCOMB: Sure, that makes sense. Well, can you give us a couple examples of tree species that are at risk for extinction?

MEYER: Yeah, absolutely. So we identified 165 threatened tree species in the US. And lots of those are pretty well-known species like oak trees, we identified 17 threatened species of oak. Ash trees, we identified four species of threatened ash. The Fraser fir, which is a really common Christmas tree. Some other really well-known trees include the California redwood and the Giant Sequoia, some of the largest organisms on Earth. And for these species, stress from fire, drought really caused decline and die off of older trees, as well as prevent the regrowth of younger seedlings in the understory.

According to the study, the top threats to American trees are pests and disease. Climate change weakens trees, increasing their vulnerability to pests like the bark beetle, which burrow into a tree’s bark as pictured above. (Photo: Immo Wegmann on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: I mean, that's really discouraging to hear, you know, the redwoods and sequoias are also some of the oldest trees in the world, you know, individuals can be older than 1000s of years old. You know, they're able to survive that long imagine all of the changes and fires and things that come through. But now, now, they're not able to survive anymore.

MEYER: Exactly. So you know, for example, California redwood and giant sequoia are both fire-adapted species. So they evolved with seasonal fire happening, but with the intensity of fires that we've been seeing, and also, the rapid rate of change that we've been seeing with our climate, plant species just can't keep up.

BASCOMB: Now, if some species die off because of climate change or pests, as you outlined, I would assume that other species would just move in and take their place. Is that right? And if so, what is at stake with the loss of biodiversity if not the actual numbers of trees?

MEYER: Right, so I think of a forest or any ecosystem really as like a tapestry. And if you start pulling out one thread, and then another, soon, the fabric is not going to be as strong, you can see through it and could be torn more easily. So ecosystems are very similar. And each thread is depending on the other one for strength and durability. So if some species start to disappear, the remaining species become more vulnerable. And also, if certain species are disappearing in a forest matrix, some of the holes that are created in the forest canopy actually become places for new invasive plants and trees to take hold. Oftentimes, the species that can survive well now are the invasive species.

BASCOMB: Right. And I believe, I mean, there's certain other plants and animals that are reliant on specific species of trees. So if you lose one type of tree, you may lose a whole lot more than just that.

MEYER: Precisely. So all of the other species that depend on these trees for survival will be in trouble. Half of the world's animal and plant species rely on trees as their habitat. So in general, the consequences of forest decline are pretty catastrophic.

Trees are keystone species that provide habitat, protection, and food for numerous other species in an ecosystem. A single oak tree, like the one pictured above, can support up to thousands of species on itself. (Photo: Cole Marshall on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: Sure, I mean, one tree could be its own ecosystem, really.

MEYER: Exactly. A single oak, for example, can support hundreds and even thousands of different species on a single tree.

BASCOMB: So trees, I mean, they serve so many functions, you know, they give us oxygen, they provide habitat, and a big one we're concerned about now is sequestering carbon. The US government is relying on trees to offset our greenhouse gas emissions. Given your paper's forecast for so many tree species, how should we be thinking about the carbon storage capacity of our forests?

MEYER: Yes, that's a great question. Forests provide 50% of current carbon storage. So mass tree planting has been looked at in recent times as sort of a silver bullet solution to the climate crisis. And often tree planting initiatives that we've seen across the globe don't factor in biodiversity factors. And we know that diverse native tree communities are more resilient. So to allow for a dynamic and adaptable future forest, each species in forest needs to have a full set of genetic tools to adapt to any future scenario. So our goal right now is to get the right trees in the right places and encourage diversity; that both species diversity and genetic diversity.

BASCOMB: Now, your study found that over 160 tree species may be endangered or threatened, but the federal government only recognizes about eight. Why are those numbers so very different?

MEYER: Yeah. So in North America, we have about 10,000 threatened plant species across the continent, and a very small minority are actually listed on the endangered species list. And that's not a new thing. We've been working within that context for decades. The reason it can take a long time through the petition and proposal process, through a review process, there's also a public comment phase. And that can take years to actually get a species on to the list. It's also worth noting that species that are listed by the Endangered Species Act receive federal protections on federal land. And so the people who are approving species for the endangered species list won't actually approve a species unless it will benefit the species. So say a species exists on only private land or on non-federal land, they won't see the value in that. So that's why we have these other assessment systems outside of the Endangered Species Act that help us keep the pulse on which species are in decline in which species are doing fine.

BASCOMB: Let me just make sure I understand this correctly. You're saying that the Endangered Species Act only applies to federal land? I mean, you can't go out and shoot a California condor, for example, even if it's not on federally-owned land. So is it different for trees for some reason?

MEYER: Exactly. So there is a difference between the protections the animals receive and the protections that plants receive. So plants are protected on federal land, but not on private land, basically.

BASCOMB: You know, another metric of species endangerment is the IUCN's Red List. The red list contains a whole lot more mammal species than tree species, even though there are as many as five times more trees than mammals. I understand there's actually a term for overlooking plant species despite their abundance. Can you tell us about that, please?

Abby Meyer is the Executive Director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International U.S. and a lead author on the 2022 risk assessment study of U.S. trees. (Photo: Courtesy of Abby Meyer)

MEYER: Yes, absolutely. So there is a tendency by people to sort of ignore plants. And we call that plant awareness disparity. Some people call it plant blindness. Really, it comes down to some of the psychological characteristics of humans and how we are drawn to organisms that we can relate to. If we can relate to an animal that moves, that maybe looks like they're expressing emotion, then it makes us care about them. And for plants, we don't have that advantage. And so they're often overlooked. For example, there are more threatened plants than threatened vertebrates and invertebrates combined. Our job is actually much bigger than the animal world. And that's only to say that only 10% of all plants have actually been assessed for their conservation status.

BASCOMB: Well, now that we know so many of our native trees are at risk of extinction, what should be done about it?

MEYER: So conservation action can really take shape in a lot of different ways. That can look like seed banking, where seeds are frozen for up to hundreds of years to buy us some time and to preserve genetic lineages. There's also growing living plants in a garden or in a conservation grove that can be used for reintroduction in the wild or breeding. There's also long-term management of species in wild populations, as well as in these living plant collections or seed orchards. So management of these species through time and that includes genetic management is really crucial as these threatened species populations are dwindling. We need society to value plants and nature so that it gets the conservation attention that it needs.

BASCOMB: Abby Meyer is the executive director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International and lead author of this study. Abby, thank you so much for your time today.

MEYER: Thank you so much for having me. It was fun.

Related links:

- Read the tree extinction risk study

- Read a summary of the risk assessment initiative

- Learn more about Botanic Gardens Conservation International

- BCGI’s Global Risk Assessment

[MUSIC: George Mamua Telek, “Midal” on Gardens of Eden, by George Mamua Telek/traditional, Putumayo World Music]

The Grand Canyon of the Atlantic Ocean

Deepwater octocoral, Anthomastus sp. (Photo: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research)

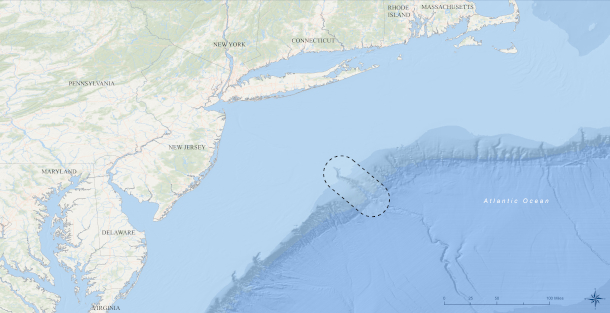

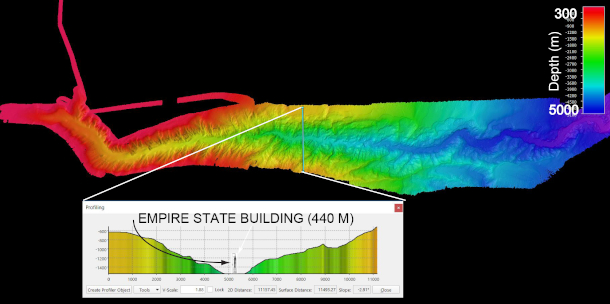

CURWOOD: Set sail southeast of New York City and about 100 miles out, you’ll be coasting above an underwater chasm far deeper than the Grand Canyon. Descending ten thousand feet into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean, Hudson Canyon is a vast gorge and ecological hotspot that’s being considered for national marine sanctuary status. That would make it the very first marine sanctuary off the coast of New York and New Jersey. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering called up Merry Camhi, director of the New York Seascape at the Wildlife Conservation Society and New York Aquarium to learn more.

CAMHI: The canyon itself is the drowned riverbed of the Hudson River, right? So it has actually cut a channel and a deep fissure into the side of the shelf. And it's down there where we have a very complex, a fragile, a biodiverse, a productive ecosystem that is characterized by a lot of different kinds of habitats and a multitude of species. It's what we like to call an ecological hotspot, it's widely recognized by scientists as a hotspot, because of the high biodiversity that's there, and the amazing productivity and diversity of the ecosystem.

DOERING: Wow. Yeah, I can imagine. I mean, I think in biology, there's this idea that when you have different environments, you tend to have a lot of different species that can take advantage of those environments and a mixing of environments. And in this case, it's, I believe, thousands of feet deep and 350 miles long. So what are the species that we can find there in this ecological hotspot?

Area proposed for Hudson Canyon National Marine Sanctuary. (Image: NOAA)

CAMHI: Yes, so you're right, the diversity of habitats means that we also have a diversity of wildlife that it can support. And we have everything from, starting at the surface, an amazing diversity of pelagic seabirds that spend most of their time offshore. I think we have like almost 20 different seabirds that had been identified there. We have 17 species of marine mammals, mostly large whales, like sperm whales, as well as a lot of different kinds of dolphins, right. There are over 200 species of fishes in there and hundreds of species of invertebrates. Four of the world's seven sea turtles also pass through or depend in some way on the riches of the canyon. And to top it off at the very bottom, we have cold water corals.

DOERING: It certainly sounds like an amazing place. And there are some like yourself who believe it's well worth protecting. So tell me about this proposal to make Hudson Canyon a National Marine Sanctuary. How did we get to this point?

CAMHI: Well, I think part of this is just recognizing that right here in these waters, right here in our own backyard, we have this amazing treasure. The Hudson Canyon is the largest submarine canyon along the US Atlantic coast. And it's also one of the largest submarine canyons in the world. It's important to our local fisheries, there are commercial and recreational fisheries out there that are worthy of protection. There are all these species, many of them endangered and threatened, some sea turtles, marine mammals, sharks and some other fishes, that depend on the canyon. And whether it's seasonally or they live there full time, that need that canyon ecosystem. And because we are a wildlife conservation organization, we decided that this was worth pursuing as a National Marine Sanctuary.

An octopus, sea star, bivalves, and dozens of cup coral all share the same overhang. (Image: NOAA/BOEM/USGS)

DOERING: So and what does that, what does that mean? You know, I mean, we have national parks, we have national monuments, we have wildlife refuges. What kind of protection does a National Marine Sanctuary afford a place like Hudson Canyon?

CAMHI: One of the main benefits that we think would happen for Hudson Canyon is that it would exclude oil and gas and mineral extraction. That's one of the most important conservation benefits. A lot of other uses are allowed as long as they are compatible with the goals and objectives of a National Marine Sanctuary.

DOERING: Uses like continued fishing or wind development, offshore wind?

CAMHI: Yes, so fishing occurs in about 98% of the sanctuary area, under the sanctuary program. And currently there are 15 national marine sanctuaries and none right here in the mid-Atlantic. So we would be the first sanctuary right here in the New York Bight and in our area and the first submarine canyon here on the Atlantic coast to be protected. It does allow for fishing, as long as fishing is sustainable. WCS believes that fishing should continue under the current authorities that manage fisheries, which is the Fisheries Service, not the National Marine Sanctuary program. Wind is also an issue here in New York, right? So we know that we have phenomenal wind resources in New York. And there is a very big push by the states of New York and New Jersey to develop those offshore wind capacity here to help reduce our dependence on fossil fuel. So WCS is supportive of offshore wind, as long as it's being done in a way that minimizes impact to wildlife and wild places, our habitats.

DOERING: Now, we've covered the endangered North Atlantic right whales quite a bit on this show. And I'm curious whether, you know, on their journey from, I think off the coast of Georgia, where they have their calves, all the way up through the coast of Massachusetts and, and Maine. Do they stop at Hudson Canyon on the way?

CAMHI: Yes, so actually, many of the great whales, including the North Atlantic right whale, pass through New York waters as they head up further to their foraging grounds, where they spend the summer, and can also pass back on their way south as they head towards their birthing grounds. One of the ways that we are able as the Wildlife Conservation Society to document this is that we have acoustic buoys that are situated in and around New York Harbor and out on the shelf, that can actually listen to the calls of whales as they are either feeding in the area or passing through the area.

Overhead view of Hudson Canyon. The transect demonstrates the width and relief of the canyon with Empire State Building for scale. (Image: NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.)

[RIGHT WHALE CALLS]

CAMHI: I think the most common sounds that we are hearing are from humpback whales.

[HUMPBACK WHALE CALLS]

CAMHI: Humpbacks are increasingly present in our local waters. Our waters are getting cleaner. The Clean Water Act from, you know, 50 years ago has really made a difference. Because as we all, many of us know, the Hudson River was a source of tremendous amounts of sewage and pollution that fed right into the canyon. And with, as our waters in the rivers and coastal waters get cleaner, so does the health of the canyon. With that comes resources like menhaden and other forage species that bring the predatory animals, like sharks, and whales, etc, to our local waters. And so we've been seeing an increase in whales, even within view of New York City, right in the harbor.

DOERING: So it sounds like an amazing place. And I would love to visit if I could, although I'm not scuba certified. And I think even the best scuba divers can't go two miles deep, certainly. [LAUGHS] But, but I am, I am wondering, you know, with such a special place, a lot of the time we have to worry these days about, or we have to wonder these days, about how it'll be affected because of climate change. And you know, the oceans are warming, they're also absorbing a lot of the CO2 that we're putting into the atmosphere, so they're becoming more acidic. So I'm wondering what effect that might have on this wonderful ecosystem and Hudson Canyon?

A pair of mating deep-sea red crabs rests on a ledge of a canyon wall. (Image: NOAA/BOEM/USGS)

CAMHI: Well, you're asking a very interesting question: How will climate change and warming oceans affect special places like deep sea canyons? And there's still a lot of uncertainty about that. We know it will have an impact, we're already seeing shifts in the distribution of species that occur in and around the canyon near the surface as the waters get warmer, right? A lot of our more southern species are starting to move northward as waters warm up. In addition, we know that warming can change the acidity of these ecosystems, it can change the amount of oxygen that's in the water, and that changes the dynamics of currents and upwelling etcetera in these canyons. How that's going to affect our wildlife, we don't really know. And one of the reasons we're really keen about having a National Marine Sanctuary here in Hudson Canyon, is because oftentimes, sanctuaries serve as, can serve as sentinel sites. They attract research and exploration and can actually help establish long term ecological monitoring there that will help us understand what the impacts are on deep sea ecosystems, and even how they will affect the resilience of coastal species and coastal communities by looking at those incremental changes and monitoring them over time. So that's one of the reasons we are really happy to see the government support the National Marine Sanctuary here, we're hoping it'll establish a long-term monitoring sentinel site.

CURWOOD: Merry Camhi, director of the New York Seascape at the Wildlife Conservation Society, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Learn more about Hudson Canyon’s proposed designation as a national marine sanctuary

- More about Hudson Canyon from WCS

- About Merry Camhi

[MUSIC: Chet Baker, “Autumn Leaves” on Jazz Moods – Cool, Sony BGM Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Delaney Dryfoos, Mark Kausch, Kuka Kahfi, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Ashley Soebroto, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth